1. Introduction

Have you ever felt the kitchen cabinets are too high to reach the utensils you want? That might be because most contemporary standards of design measurements are derived from male-centric dynamics without considering gender-based physical differences. I believe that most women have experienced unfit designs in their daily lives, especially in the realms of architecture and its subfields — interior design and furniture design. Within modernism, male-centric design standards often prioritize functionality and standardization thus neglecting other elements like body movements and variations. Such standards require users to adjust the design, that is, the designs are manipulating the people in the space since not everyone can perfectly fit into the standardized designs. Alternately, women designers attempt to subvert such relationship from the male-centric standards, creating designs that are flexible and comfortable to meet ergonomics and cater to diverse body needs. Besides highlighting their needs, female designers are also challenging male-centric norms by bringing up spaces excluded by original standards to the public sight. While other researchers in similar fields, like Catharine Rossi, Lance Hosey, and Cheryl Buckley, focus on the process of female designers striving in this field, this article aims to explore the gender dynamics in architecture and design and the ongoing struggle of sexism.

2. Designs under Male-Centric Domain

To be more specific, when talking about design standards in modernism, undoubtedly, the figure commonly used to represent all people would be a white male body. Looking forward to solving all problems with one universal solution of producing one-size-fits-all designs, such male-centric standards unintentionally enlarged the gender bias. Modernist designers also tended to largely ignore body mechanics and believed the human body was a static object. It is quite impossible for users to stay still when interacting with architecture and furniture, so what they could do with standardized designs is to make bodies adjust to the products.

In examining how male-centric design standards affect design within the whole architectural field in detail, it is essential to mention and evaluate two famous examples to show the limitations and rigidity of the standards.

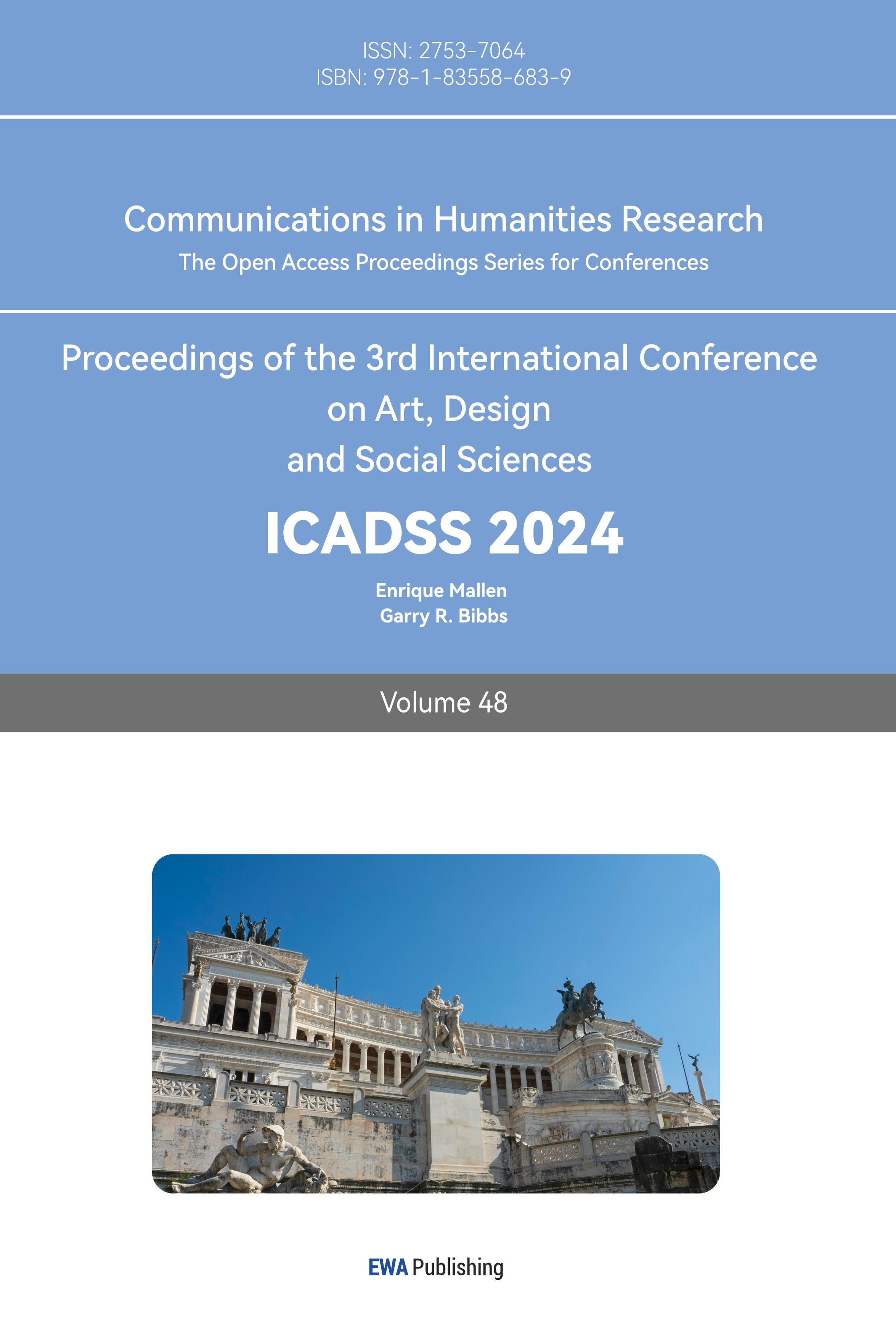

For instance, the Scale of Modulor established by Le Corbusier (figure 1) in the 20th century introduces a standard measurement for architecture and furniture. This scale system, using the average measurement of European white male figures, completely excludes women, as well as all males other than the ones in the diagram. Everybody else, when experiencing space or furniture produced upon Modulor, would be forced to adapt their bodies to what is unreasonable for them. Given this narrow and discriminatory view of the ideal human form in design, as Lance Hosey argues in Hidden Lines: Gender, Race, and the Body in "Graphic Standards", prejudice and oppression against gender, race, and body have existed since the earliest times, and even though many designers have been committed to broadening such design standards, hardly can they escape such norms. [1]

Figure 1: Modulor measurements [2]

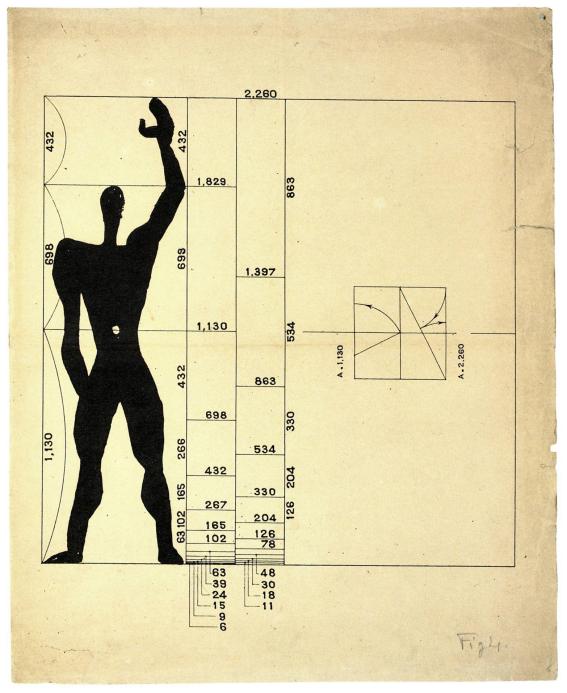

Another example worth noting is Villa Muller, a modernist architectural masterpiece designed by Adolf Loos in 1930. This house has long been praised for its innovative use of space and interior design. In Beatriz Colomina’s Privacy and Publicity, she stated that the locations of windows and the arrangement of the space and fixtures all aimed to create a sense of security. As males are dominating the world, they are afraid of losing what they already have, so they always feel anxious about their insecurity, and that would probably be the reason why they are always seeking complete manipulation.[3] In architecture, this issue could be solved by blurring or eliminating boundaries between interior and exterior, private and public in their own properties, From a gender aspect, the inner hollows and windows (figure 2.) in Villa Muller comply with males’ needs, and they are not only blurring the spaces in a physical sense but also making the boundaries among occupants there vague. When one is standing at the starting point of the red arrows in figure 3, anyone else who is in the house becomes a subject being monitored by that person, everything they are doing would be noticed by that person, thus there is no more privacy, and hierarchy is produced inside the space. Everyone being watched by the owner of the house would be oppressed and forced to adapt to the condition of losing privacy and being inferior within this dwelling.

Figure 2: Interior of Villa Muller: inner hollows and windows [4]

Figure 3: Plan, section, and oblique showing that openings inside allow occupants’ sight (red arrows) to travel through the house and to the outside [5]

In both of the two instances mentioned above, standardized designs in modernism are revealed as rigidity and control over the users, the thing itself transcends humans, but should not the design be people-centric rather than object-centric? Indeed, the idea of standardized design itself is a problem since the human body is never static and comfort is never a fixed concept.

3. Female Designers’ Attempts

At the same time when male modernist designers and architects were promoting rigid standards, females in this field were dedicated to challenging the norms, producing designs that are reflected on body dynamics better. Unfortunately, their impact was limited to a small range. Why has the influence of these female designers been so small, and what is the cause of gender-based design differences in architecture? Historically, women have been reckoned as inferior to men in societal roles and status and have been suppressed ever since the advent of patriarchy. The patriarchal society stereotypes women as emotional and irrational, lacking logic and intelligence so women can hardly satisfy most of the males' domain. Whereas architecture is considered a male-dominated and high-culture profession that needs to be separated from other popular cultures[5], smaller-scaled fields in architecture, facing a similar situation as females do, are thus designated to women, such as interior design, furniture design, and textiles.[6] That said, women do not choose to participate in such fields based on their free will but are forced to enter those “inferior” professions. They are prisoned into these smaller fields by males so that females can hardly gain the power and status to fight against male domination over architecture, or to put it in a broader sense, patriarchy. Additionally, women are also forced to spend more of their time in domestic and reproductive work, and that could explain why women designers shape distinct angles and views other than those of male designers.

Women designers, however, have started their journey trying to break the standard set by male designers for modern architecture, even if they are only allowed to work in “trivial and inferior” areas and make minimal changes and they might still be trapped in the patriarchal society. Although fully overthrowing or escaping from patriarchy seems impossible, women are continuously working towards bringing themselves a more comfortable life at least, and ultimately emancipation. Given this scenario, feminine designs in architecture and interior are characterized by flexibility and mobility, which never stay still.

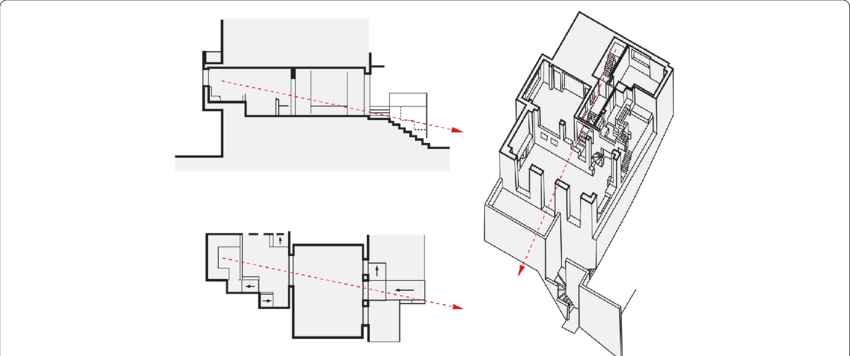

Back in 1927, Le Corbusier proposed typical resting postures and left the job to solve this problem to Charlotte Perriand, a French woman architect and designer. Charlotte Perriand, then in 1928, designed the famous lounge chair (figure 4) – chaise longue basculante: a flexible chaise that could swing in the steel holder – accordingly. This lounge chair made by Perriand allows users to either lie or sit or whatever posture they would like to be depending on it, is flexible and functional at the same time, establishing the sense of designing upon users’ needs and letting the users take total control over the objects. Imagine sitting on the chair straight at the beginning, and ten minutes later, your neck and back start to hurt, but you do not have to find somewhere else to lie down, instead, you change your position on this chair until you finally find a way to arrange your body comfortably on it and fall asleep. It is the chair that provides you with an adjustable way to match your body dynamics rather than asking you to get used to the limited design.

Figure 4: Lounge chair designed by Charlotte Perriand [7]

However, Perriand’s contribution had been faded and her co-authorship had been concealed by Corbusier. Corbusier owned the authorship of the lounge chair solely in the following decades because he was much more famous and most importantly but simply because he was a male.[8] In accordance with the example of Perriand’s lounge chair, could be traced back to the early nineteenth century when women started to change the standardized design from this subfield of architecture, furniture design. It could also be conjectured that female designers like Perriand might have made numerous other attempts to challenge the standard but hardly could people recognize their achievements, same to the condition in this case. Many of Perriand’s designs later, still, followed Corbusier’s instructions, although their design concepts and styles were indeed very compatible, it was nearly impossible to ignore the oppression of female designers by male designers behind. Such condition remained until she broke up with Corbusier in the late 1930s. Furthermore, Perriand was already a very famous female designer, relatively speaking, but her contribution to the works was still deliberately downplayed or even erased when she worked with Corbusier, not to mention the harsh situation for thousands of unknown female designers and missing records of their contributions to feminine design at that time. Besides, in this famous photo (Figure 4) Perriand’s face is turned away from the camera, and she cannot return the gaze and present herself as a full subject with a dynamic body and mind. Audiences, instead, see her body projected on a white wall behind, shifting her three-dimensional body into a two-dimensional outline and shadow, which is fixed on the so-called neutral canvas – the white wall. But as Colomina argues the white wall is not neutral or objective, it indicates the site of control, matters displayed on which are placed to the position to be watched and judged by others who get domination. This photo reveals another kind of fixation of design.

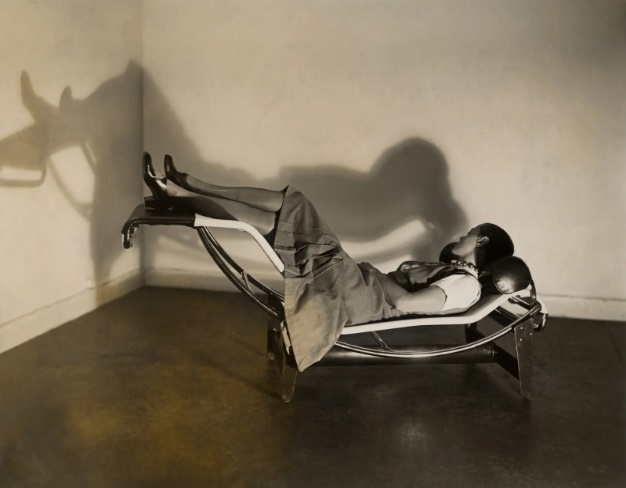

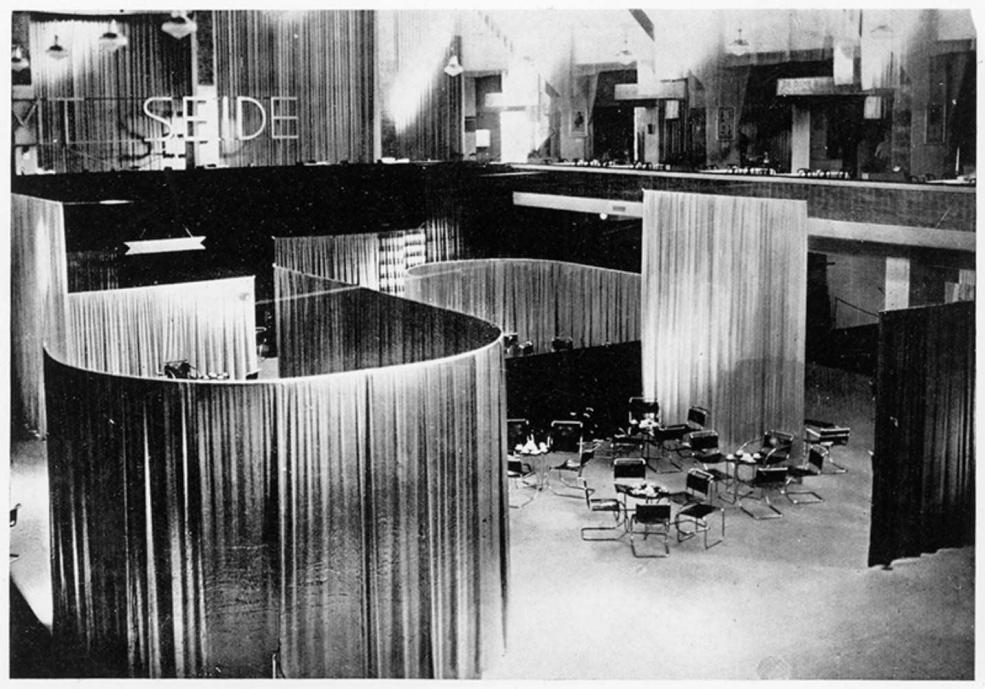

Yet there were other female designers who succeeded in breaking the standardized design rules and were acknowledged by society. Also in 1927, a famous female artist, Lily Reich, made a stand for the German Silk industry in an exhibition related to women’s fashion with Mies van der Rohe, a modern architect known for his famous dictum ‘less is more’. In this project, Reich took advantage of curtains to define spaces. The whole area was designed as an opening space with the only separation of the hanging silk and velvet curtains of various colors (figure 5). Normally, interior division used to be done by partition walls, which were fixed in position once built, and it was

Figure 5: Lily Reich uses curtains as space dividers [9]

impossible to change the space arrangements, whereas the use of curtains provided the innovative idea of softness and flexibility.[10] The use of curtains permitted the exhibition space to be dynamic at all times, as the curtains could be opened and closed according to varied needs, allowing for different spatial divisions. At the same time, since the position of the curtains is determined by its track, the variability of the space can be further increased by changing the track. Moreover, Lily Reich influenced Mies van der Rohe’s architectural design to a great extent, adding more vividity, colors, and curvature elements to his later projects.[11] For example, Mies van der Rohe adopted Lily Reich’s design of free-standing glass walls in his Barcelona Pavilion. It is also important to note that the free-standing glass walls contribute to the free plan and allow more interaction with exterior views and nature, though not as changeable as the curtains. These projects designed by Lily Reich reveal the attempts to break the fixed spatial division strategy and permit versatile area composition, and point to a different idea of space itself that curves and boundaries cannot be delineated or fixed permanently, reflecting the feminine idea of flexibility, empathy, and inclusiveness.

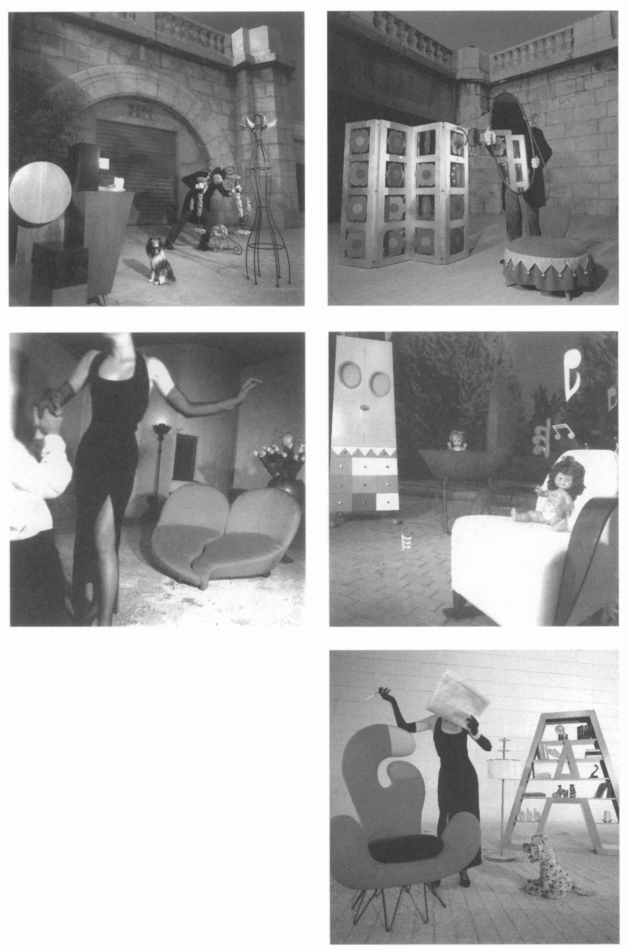

Later in the 1990s, as women's status improved gradually, more and more women started to enter the architecture and design industry, and more feminine and rule-breaking perspectives emerged or were brought up to expose the shortcomings of standardized designs and content disregarded by male designers. In particular, the women-only exhibition of La casa que ríe (The Laughing Home) at the 1994 Abitare il Tempo furniture fair in Verona invited nine female designers to produce three pieces of furniture each, twentyone pieces in total, decorating their ideal dwelling composed by seven spaces. Although women have traditionally been the domestic figures, they have lived under the cloud of masculine domination and never actively engaged in designing the space they spend most of their time, so this exhibition aimed to reverse such a relationship, asking females to be the creators of their spaces. It is worth noting that these nine female designers broke the conventional composition of the home, defining the seven spaces as receiving, playing, loving, eating, playing, rocking, and beauty, spaces put into peripheral by males (figure 6).[12] In this event, all the female designers either celebrated feminine elements or satirized stereotypes of women through their designs. Spaces for personal care (beauty), childhood (playing), and motherhood (rocking) are compressed or eliminated in standardized interior designs, replaced by large living rooms or studying rooms which are seldom used by members other than the male owner in the family. On the other hand, based on standardized design and stereotypes about women, spaces like loving and beauty which are related to women should be the most private parts of a house as women should not show up a lot in social activities. But who says spaces related to males (socialbility) like the living room must be the most spacious and important place in the house? Can't the cloakroom or the kitchen be the largest room and located in the center of the house? The Laughing Home did a brilliant job of bringing marginalized spaces to light and satirizing standardized design rubrics by emphasizing these spaces.

Figure 6: Spaces presented in The Laughing Home project [13]

The transformative approach of The Laughing Home indicates female designers’ ability to comprehensively understand the underlying principles of design which should be user- or people-centric and display the value of diverse and inclusive design norms. This shift signifies the journey toward a more equal and just architecture and design industry.

4. Conclusion

But does this approach of flexible and user-centric designs truly count as breaking the narrow standards or, that says, the male domination in architecture? Under the circumstances of defining male-centric design as fixation and standardization, it could be claimed that female designs indeed break the standard by prioritizing flexibility and comfort to accommodate everyone. However, large-scale discrimination and sexism still occur in architecture and interior design. Women designers are trapped in the standards created by patriarchy as they are not breaking the stereotype that females are more inclined toward domestic, reproductive, and emotional work.[14] Yet obviously, it is hard for women to upend these norms while still operating under patriarchal constraints.

Despite this, as in all the cases mentioned, women have taken small steps to improve their living environment to the maximum extent possible under limited circumstances. Although this does not seem to break the norms entirely and directly, it is the beginning and a necessary step towards improving women's living environment and quality and achieving the ultimate equality and justice they demand.

Ultimately, with all such feminine designs in the architecture, interior, and furniture industries, female designers devote themselves to challenging the male-centric domain and standards in these fields, especially in the contemporary era, and produce tremendous efforts and influence in creating innovative designs to improve the quality of life of all those outside the norm. Perhaps one day, the room arrangement in every home is different depending on each family’s needs, and maybe the function of rooms could even vary in different time periods, not only small furniture pieces could be flexible, but also the entire house could be changeable as well. Also, a completely equal and fair design field and social environment for all people can be envisioned one day in the future.

References

[1]. Hosey, Lance. “Hidden Lines: Gender, Race, and the Body in ‘Graphic Standards.’” Journal of Architectural Education (1984-), vol. 55, no. 2, 2001, pp. 101–12. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1425611. Accessed 6 Aug. 2024.

[2]. Fig. 1. Le Corbusier. Modulor. 1950. JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.16513680. Accessed 24 July 2024.

[3]. Colomina, Beatriz. “Privacy and Publicity : Modern Architecture as Mass Media.” MIT Press eBooks, 1994, ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA28150954.

[4]. Fig. 2. “The Villa Müller.” Adolf Loos, 17 Aug. 2017, adolfloos.cz/en/villa-muller. Accessed 25 July 2024.

[5]. Fig. 3. Del Campo, Matias. “Deep house - datasets, estrangement, and the problem of the new.” Architectural Intelligence, vol. 1, no. 1, 29 Aug. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s44223-022- 00013-w.

[6]. Rossi, Catharine. “Furniture, Feminism and the Feminine: Women Designers in Post-War Italy, 1945 to 1970.” Journal of Design History, vol. 22, no. 3, 2009, pp. 24357.JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40301449. Accessed 16 July 2024.

[7]. Fig. 4. Giovannini, Joseph. “Charlotte Perriand, Stepping out of Corbusier’s Shadow.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 21 Nov. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/11/21/arts/design/charlotte-perriand-le-corbusier-review.html. Accessed 25 July 2024.

[8]. Giovannini, Joseph. “Charlotte Perriand, Stepping out of Corbusier’s Shadow.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 21 Nov. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/11/21/arts/design/

[9]. Fig. 5. Fabrizi, Mariabruna. “‘Café Samt and Seide’ by Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe and Lilly Reich (1927).” SOCKS, 10 Feb. 2018, socks-studio.com/2016/02/29/cafe-samt-seide-by-ludwig- mies-van-der-rohe-and-lilly-reich-1927. Accessed 26 July 2024.

[10]. Franco, José Tomás. “Curtains as Room Dividers: Towards a Fluid and Adaptable Architecture.” ArchDaily, 2 Dec. 2023, www.archdaily.com/936540/curtains-as-room-dividers-towards-a-fluid-and-adaptable-architecture. Accessed 25 July 2024.

[11]. Esther da Costa Meyer. “Cruel Metonymies: Lilly Reich’s Designs for the 1937 World’s Fair.” New German Critique, no. 76, 1999, pp. 161–89. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/488661. Accessed 18 July 2024.

[12]. Martínez, Javier Gimeno. “Women Only: Design Events Restricted to Female Designers during the 1990s.” Design Issues, vol. 23, no. 2, 2007, pp. 17–30. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25224103. Accessed 31 July 2024.

[13]. Fig. 6. Martínez, Javier Gimeno. “Women Only: Design Events Restricted to Female Designers during the 1990s.” Design Issues, vol. 23, no. 2, 2007, pp. 17–30. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25224103.Accessed 31 July 2024.

[14]. Buckley, Cheryl. “Made in Patriarchy: Toward a Feminist Analysis of Women and Design.” Design Issues, vol. 3, no. 2, 1986, pp. 3–14. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1511480. Accessed 25 Aug. 2024.

Cite this article

Yu,R. (2024). Sexism in Interior: Feminine Design in a Male-Centric Domain. Communications in Humanities Research,48,97-105.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Art, Design and Social Sciences

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Hosey, Lance. “Hidden Lines: Gender, Race, and the Body in ‘Graphic Standards.’” Journal of Architectural Education (1984-), vol. 55, no. 2, 2001, pp. 101–12. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1425611. Accessed 6 Aug. 2024.

[2]. Fig. 1. Le Corbusier. Modulor. 1950. JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.16513680. Accessed 24 July 2024.

[3]. Colomina, Beatriz. “Privacy and Publicity : Modern Architecture as Mass Media.” MIT Press eBooks, 1994, ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA28150954.

[4]. Fig. 2. “The Villa Müller.” Adolf Loos, 17 Aug. 2017, adolfloos.cz/en/villa-muller. Accessed 25 July 2024.

[5]. Fig. 3. Del Campo, Matias. “Deep house - datasets, estrangement, and the problem of the new.” Architectural Intelligence, vol. 1, no. 1, 29 Aug. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s44223-022- 00013-w.

[6]. Rossi, Catharine. “Furniture, Feminism and the Feminine: Women Designers in Post-War Italy, 1945 to 1970.” Journal of Design History, vol. 22, no. 3, 2009, pp. 24357.JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40301449. Accessed 16 July 2024.

[7]. Fig. 4. Giovannini, Joseph. “Charlotte Perriand, Stepping out of Corbusier’s Shadow.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 21 Nov. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/11/21/arts/design/charlotte-perriand-le-corbusier-review.html. Accessed 25 July 2024.

[8]. Giovannini, Joseph. “Charlotte Perriand, Stepping out of Corbusier’s Shadow.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 21 Nov. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/11/21/arts/design/

[9]. Fig. 5. Fabrizi, Mariabruna. “‘Café Samt and Seide’ by Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe and Lilly Reich (1927).” SOCKS, 10 Feb. 2018, socks-studio.com/2016/02/29/cafe-samt-seide-by-ludwig- mies-van-der-rohe-and-lilly-reich-1927. Accessed 26 July 2024.

[10]. Franco, José Tomás. “Curtains as Room Dividers: Towards a Fluid and Adaptable Architecture.” ArchDaily, 2 Dec. 2023, www.archdaily.com/936540/curtains-as-room-dividers-towards-a-fluid-and-adaptable-architecture. Accessed 25 July 2024.

[11]. Esther da Costa Meyer. “Cruel Metonymies: Lilly Reich’s Designs for the 1937 World’s Fair.” New German Critique, no. 76, 1999, pp. 161–89. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/488661. Accessed 18 July 2024.

[12]. Martínez, Javier Gimeno. “Women Only: Design Events Restricted to Female Designers during the 1990s.” Design Issues, vol. 23, no. 2, 2007, pp. 17–30. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25224103. Accessed 31 July 2024.

[13]. Fig. 6. Martínez, Javier Gimeno. “Women Only: Design Events Restricted to Female Designers during the 1990s.” Design Issues, vol. 23, no. 2, 2007, pp. 17–30. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25224103.Accessed 31 July 2024.

[14]. Buckley, Cheryl. “Made in Patriarchy: Toward a Feminist Analysis of Women and Design.” Design Issues, vol. 3, no. 2, 1986, pp. 3–14. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1511480. Accessed 25 Aug. 2024.