1. Introduction

Surrounded by the salty sea wind in a Putian village, everyone grew up listening to stories of our sea goddess Mazu. Over time, the identities and structures of Mazu belief vary across regions, influenced by history, politics, and interactions with other religions. The evolving belief in Mazu is reflected in the diverse development strategies of Mazu temples, some embracing change while others remain unchanged.

In ancient times, religious buildings were first built in terms of worship. As Zhang, Wu, & Liu [1] assert, devotees built religious buildings in order to show their piety, this is primary stance reflected the materiality of Mazu temples. But in current society, religious buildings are not only the functional architectures, but also present other symbolization beyond religion. Verkaaik [2] suggested that religious buildings contribute to identity and community besides religious experience. Studying on this phenomenon can analyze the evolution of Mazu belief and the broader influence of religious architecture, and the significance of focusing on the phenomenon of change itself. And provide a perspective on the reinterpretation of Mazu temple as a cultural symbol in the context of religion and social identity.

Most previous Chinese scholar’s studies focus on how the Mazu belief itself spreading all around world and what evolution did this faith experienced, so that the architectural academic study around Mazu belief always considered as an elements of aesthetics study without systematic researches. How the religious buildings reflect the Mazu belief? In what context these buildings would be analyzed as a space parallel to other religious buildings? How to identify the Mazu temples beyond the religious buildings?

2. Background of Mazu Belief

Born in 960 on Meizhou Island, Mazu, originally as a daughter of a fisherman, possessed magical abilities to rescue those in maritime disasters. After her selfless sacrifice at sea in 987 people can’t find her body, in some beautiful wishes she was believed to have ascended to heaven, becoming a goddess. Soon local people established a rudimentary small temple in her hometown to worship her, which was the earliest Mazu temple in the world. The establishment and expansion of the earliest Mazu temple between 1023-1032 marked the beginning of her widespread worship, but initially focused on maritime safety only in this period.

The earliest title for Mazu was Wu (witch, from folk) and Furen (madam, from court). Mazus influence gradually expanded with the development of ancient Chinese shipping industry, starting from Fujian and spreading along waterways. Therefore, Mazu temples historically located near waterways to ensure her protection for sailors, reflecting the belief in her safeguarding power in areas where her temples exist. Starting from the Song Dynasty (960-1271), with the increase of maritime trade, the ocean gradually became an important place of activity in ancient China. However, the danger of the sea has always accompanied sailors' every voyage, so the image of Mazu as a sea protector god gradually gained attention

In the13th century (Yuan Dynasty), imperial court upgraded the title of Mazu to be Tianfei (concubine of heaven) for safeguarding the food transport in waterways. In 14-15 centuries (Ming Dynasty) and 16-19 centuries (Qing Dynasty), it is a time when the Chinese imperial court focuses on developing maritime transportation and conducting maritime wars, and Mazu became Tianhou (empress of heaven) officially. Due to the court's emphasis, the people also began to believe that Mazu had the strongest power to bless everything people prayed for. Since then, the goddess’s role diversified to including blessing victory in naval battles, rain and conception. The function of Mazu has expanded from protecting maritime safety to blessing victory in naval battles, which may be related to her role as a protector of the country. Under the official promotion, her image is closely linked to national interests, and at this point, the Mazu faith has actually completed the transformation from a local belief to a symbolic spiritual totem.

Through the continuous evolution of Mazu belief over the past thousand years, we can find that its status in the hearts of Chinese people has become increasingly high. This situation is reflected in the construction and specifications of Mazu temples.

3. Mazu Belief in Architectures

Mazu, both in life and as a deity, is closely linked with water, symbolizing her domain over the ocean and sky. The Mazu temple in Meizhou obviously features water-related theme, such as ocean patterns and aquatic creatures, emphasizing her status as a water goddess. Those quantity elements can be seen on the entrance of the Tianfei Palace (figure 1) before entering. It’s worth mentioned that the kinds of Jishou脊兽 (three-dimensional animal roof decorations) are ranked in ascending order according to the roof hierarchy, with fish at the bottom and the top with loongs- traditional Chinese symbols of nobility, and are also considered gods in charge of seas. But even though loongs holds a higher status than others, it has not qualified to be on par with Mazu, which seems to once again demonstrate that the status of Mazu is far higher than that of other sea gods.

Figure 1: The Shengzhi Gate and Yimen Square

Note. Located at the entrance of the west axis of Mazu Temple in Meizhou island.[3]

The temple's blue color scheme, cloud patterns, and raised eaves symbolize connections to the ocean and sky, reflecting Mazu's heavenly function. Ruitenbeek K. [4] found evidence in a picture from a page of seven view of Meizhou, which illustrated some scrolling cloud in the corner that can echoing the band of clouds in the corresponding woodcut in Mazu temple, can relate Mazu’s heavenly story and buildings. The sky-contact trend of eaves in local’s belief is a way to send their wishes to where the goddess live. In this context, architecture makes it possible to imagine Mazu has a goddess connecting sea and sky. Without the temple this connection cannot be emphasized or articulated. Besides those natural elements integrating with Mazu’s function, due to her amazing story, many excellent qualities are considered to be consistent with the views advocated by other religions, especially Buddhism.

Mazu beliefs started to integrate with Buddhism in China from the Yuan dynasty. Guanyin, original name was Avalokitesvara in Buddhism, had changed identity from male to female and became a goddess in China. ‘……while both Guanyin and Tianfei are compassionate goddesses of mercy. All are associated with water.’[5]The fusion of Guanyin and Mazu is evident in Mazu's statues, which reflecting Buddhist sculptural influence with a round face and benevolent expression. In early period the Mazu statues remained precise styles (figure 2), but after absorbed Buddhist aesthetics (figure 3) they possessed softer lines and dynamics. Now it can be a common characteristic in large-scale Mazu Temple complexes' stone statues (figure 4).

Figure 2: Mazu and her servant.

Note. Early Qing Dynasty wood carving. Discovered by local residents in a well. [6]

Figure 3: White Glazed Guanyin Statue.

Note. Made in Qing Dynasty. The face has a kind expression. [7]

Figure 4: The biggest Mazu sculpture in Fengshan Temple in Shanwei

Note. Made of stone, and all raw materials come from Meizhou. [8]

Mazu temples have evolved in regions like Mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, moving from coastal areas to commercial centers during the Ming and Qing dynasties and blending with local architecture. This shift suggests a transition for Mazu believers from seeking blessings to promoting Mazu faith and cultural unity. In China, Mazu believers tend to spread. Therefore, the Mazu belief is actually in a state of development.

Based on traditional Chinese culture and religious beliefs, placing a positive goddess as the core of worship, her female spirit of compassion, and salvation is enough to make the local people let go of their resistance emotions. Mazu Temples, rooted in Chinese tradition, have evolved from simple Mazu shrines to cultural harmony spaces. In Tianjin's Tianhou Palace, locals have set up animal gods as a side hall for worship. In fact, the belief in Mazu is in a slow state of morphological change in China, but in overseas regions, it is another form that is close to solidification.

4. Faith and Buildings Overseas

The Mazu belief introduced to Japan via Ryukyu, these two places are the earliest overseas regions to accept the Mazu belief. In the Ming and Qing dynasties' smuggling trade, Chinese communities formed in Nagasaki. At that time, the Tokugawa Shogunate strictly prohibited foreigners from spreading Christianity. Because of religious panic, political struggles, and conflicts of interest in foreign trade, Christians were deeply persecuted in Japan, and anyone found to be promoting Christian doctrine would be arrested or even executed.

In this social background, except the Buddhism, which had nearly developed into a form accepted by Japan government, it seems that all foreign faiths are subjected to extreme scrutiny to determine whether they belong to Christianity. Mazu, as the goddess of mercy, is likened to Virgin Mary. From the name Mazu, the pronunciation Ma in Mandarin literally means mother and it obviously can connect with the Virgin Mary due to the maternal essence. In an article on the study of goddess beliefs in the Philippines, the author, ARISTOTLE C. DY, points out that people worship Mazu and the Virgin Mary in same temple or church in some regions. ‘Chinese devotees consider at least three images of the Virgin Mary in the Philippines as Christian emanations of Mazu.’[9]. As an Asian country that also receives Chinese maritime immigration culture and beliefs, if Mazu is seen as Virgin Mary in the Philippines, a similar syncretism may occur in Japan. Zhuang and Liu [10] also assume that despite differences, Mazu's image and divine power outshine local Shinto, leading to co-veneration in shrines.

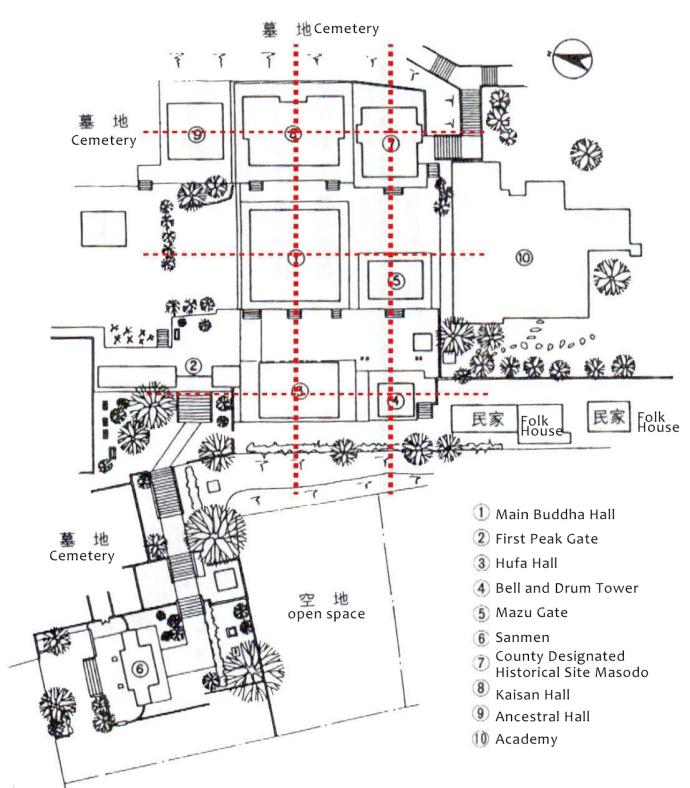

It seems difficult to argue their own Chinese beliefs with the government especially when their goddess was in a robe and with a halo behind her head in universal imagines. Chinese immigrants, to safeguard their faith under religious persecution, constructed Buddhist temples to subtly honor Mazu. The Tang Sanji Temples唐三寺,including Kofukuji兴福寺, Fukusaij福济寺, and Soufukuji崇福寺(figure 5and figure 6),were built in this period, which were the most representative three religious buildings.

Figure 5: The Masodo (Mazu Temple) in Soufukuji, Japan.

Note. This temple built in 17 century. [11]

Figure 6: The architectural plan of Soufukuji Temple

Note. The Masodo at position ⑦, at the farthest end. [12]

The simple red columns of Soufukuji's Masodo might symbolize a blend of Shinto and Mazu, which just like the Japanese local faith Shinto religious buildings Torii.,but that’s as far as it goes. The temple's construction uphold the style of Chinese Buddhist sect Houbakushyu, which reflecting the aesthetic styles of China, maintaining their distinct characteristics rather than merging with local Japanese styles.

With parallel axes for Buddhist and Mazu temples, indicates a separate worship of Mazu within a Buddhist framework. Mazu was not absorbed into Buddhism and not became a Buddhist deity. The independent architectural layout parallel to the axis of Buddhist architecture means that Mazu belief is equal to Buddhism in this space. There is no invasion or annexation, but rather a spatial dimension of dialogue.

Not only square continuous pattern hollowed out on the guardrail, but also sea and sky elemental pattern on beams evoke an image of the decorative structures of Chinese architecture. And the absence of Jishou on roofs for stylistic harmony, further illustrate the temples' dual cultural identity. The Mazu faith is irrefutable as a spiritual symbol of the unity and homesick of overseas Chinese, which may be the reason why she has remained independent overseas as a bond. Therefore, Mazu temples overseas basically follow the specifications of Chinese Mazu temples, retaining the most original palace layout, symbolizing the residence provided for Mazu herself and her attendants. Despite the challenges, the Mazu belief still maintaining its distinct worship space and cultural expression in Japan. The design of Mazu architecture in Japan can also be seen as a symbol of reconciliation and unity, promoting dialogue and understanding between different groups by creating inclusive and shared spaces.

5. Conclusion

During the early development of Mazu belief in China, it assimilated elements from various religious systems, enhancing its political influence through official recognition and popular worship. In a diverse landscape of local beliefs, the acceptance of Mazu belief posed a significant challenge, leading to the construction of diverse Mazu temples across China.

Mazu belief, nearing maturity when it spread via sea routes. Although the worship spirit centered on the goddess of mercy is inclusive and peaceful, at the same time, this belief belonging to the Chinese native maritime civilization itself has a strong independence and even exclusivity. It is no longer easy to be absorbed by the local beliefs of the region where it is spread. In this context, Mazu temples seems to have become portable space like sanctuaries, dividing the extremely pure Chinese spiritual realm in the territory of others. This also reflects the strategy of the earliest overseas Chinese to form Chinese settlements rather than integrate into local society, as well as their compromising attitude of being communicators rather than invaders. As religious buildings, Mazu temples are not only the center of faith, but also an important place for cultural inheritance and spiritual cohesion. They carry local history and national culture, and become a bridge connecting the past and the present.

References

[1]. Zhang, Y., Wu, C., & Liu, X. (2023). The Development and Modern Transformation of Material Culture in the Worship of Mazu. Religions, 14(7), 826. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070826

[2]. Verkaaik, O. (2013). Religious Architecture: Anthropological Perspectives. In O. Verkaaik (Ed.), Religious Architecture: Anthropological Perspectives (pp.7–24). Amsterdam University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wp6sx.3

[3]. The Imperial Edict Gate and Yimen Square.[Photograph].(n.d.).Retrieved from: https://www.mzmz.org.cn/zmjdjs.html?newsid=2363191&_t=1710661366 (Accessed:25 July 2024)

[4]. Ruitenbeek, K. (1999). Mazu, the Patroness of Sailors, in Chinese Pictorial Art. Artibus Asiae, 58(3/4), 281–329. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250021

[5]. Irwin, L. (1990). Divinity and Salvation: The Great Goddesses of China. Asian Folklore Studies, 49(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.2307/1177949

[6]. Wooden Carving Mazu and Maid. [Photograph].(n.d.). Retrieved from: http://www.mazuworld.com/index.php?m=content&c=index&a=Show&catid=55&id=10481 (Accessed:4th August 2024)

[7]. White Glazed Guanyin Statue.(n.d.).[Photograph].The Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Retrieved from: https://www.dpm.org.cn/collection/sculpture/233546.html

[8]. Zmshao. (2021). The Biggest Mazu Sculpture in Guangdong, China. [Photograph].Retrieved from: https://www.shanwei.gov.cn/swswgltj/gkmlpt/content/0/662/post_662452.html#1088 (Accessed:25 July 2024)

[9]. DY, A. C. (2014). The Virgin Mary as Mazu or Guanyin: The Syncretic Nature of Chinese Religion in the Philippines. Philippine Sociological Review, 62, 41–63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43486492

[10]. Zhuang, L., & Liu, K. (2023). Cultural Exchange in the East Asian Seas in Light of the Acceptance of Mazu Beliefs by Japanese Sea Gods. Religions, 14(3), 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030361

[11]. Hokki.(2022). The Mazu Temple.[Photograph] Retrieved from: https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B4%87%E7%A6%8F%E5%AF%BA_(%E9%95%B7%E5%B4%8E%E5%B8%82) (Accessed:25 July 2024)

[12]. Li, Q. (2022). Schematic diagram of Soufukuji.[Image]. Retrieved from: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_17188695 (Accessed:31 July 2024)

Cite this article

Yu,F. (2024). The Metamorphosis of Mazu Belief and the Reconstruction of Mazu Temples. Communications in Humanities Research,48,84-90.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Art, Design and Social Sciences

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Zhang, Y., Wu, C., & Liu, X. (2023). The Development and Modern Transformation of Material Culture in the Worship of Mazu. Religions, 14(7), 826. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070826

[2]. Verkaaik, O. (2013). Religious Architecture: Anthropological Perspectives. In O. Verkaaik (Ed.), Religious Architecture: Anthropological Perspectives (pp.7–24). Amsterdam University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wp6sx.3

[3]. The Imperial Edict Gate and Yimen Square.[Photograph].(n.d.).Retrieved from: https://www.mzmz.org.cn/zmjdjs.html?newsid=2363191&_t=1710661366 (Accessed:25 July 2024)

[4]. Ruitenbeek, K. (1999). Mazu, the Patroness of Sailors, in Chinese Pictorial Art. Artibus Asiae, 58(3/4), 281–329. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250021

[5]. Irwin, L. (1990). Divinity and Salvation: The Great Goddesses of China. Asian Folklore Studies, 49(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.2307/1177949

[6]. Wooden Carving Mazu and Maid. [Photograph].(n.d.). Retrieved from: http://www.mazuworld.com/index.php?m=content&c=index&a=Show&catid=55&id=10481 (Accessed:4th August 2024)

[7]. White Glazed Guanyin Statue.(n.d.).[Photograph].The Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Retrieved from: https://www.dpm.org.cn/collection/sculpture/233546.html

[8]. Zmshao. (2021). The Biggest Mazu Sculpture in Guangdong, China. [Photograph].Retrieved from: https://www.shanwei.gov.cn/swswgltj/gkmlpt/content/0/662/post_662452.html#1088 (Accessed:25 July 2024)

[9]. DY, A. C. (2014). The Virgin Mary as Mazu or Guanyin: The Syncretic Nature of Chinese Religion in the Philippines. Philippine Sociological Review, 62, 41–63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43486492

[10]. Zhuang, L., & Liu, K. (2023). Cultural Exchange in the East Asian Seas in Light of the Acceptance of Mazu Beliefs by Japanese Sea Gods. Religions, 14(3), 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030361

[11]. Hokki.(2022). The Mazu Temple.[Photograph] Retrieved from: https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B4%87%E7%A6%8F%E5%AF%BA_(%E9%95%B7%E5%B4%8E%E5%B8%82) (Accessed:25 July 2024)

[12]. Li, Q. (2022). Schematic diagram of Soufukuji.[Image]. Retrieved from: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_17188695 (Accessed:31 July 2024)