Abstract: Race and race-related issues are pervasive in the United States, causing detrimental consequences at individual and societal levels. Not only in the United states, racial conflict also exists in racially homogeneous countries, such as China, given the rising economic development and cultural communications between Chinese society and other nations. The present article aims to reveal the development of racial attitudes among Chinese adolescents and adults. We assessed implicit and explicit racial attitudes toward Black and White people among 60 Chinese participants (M age = 18.04; 34 female). Participants’ implicit racial attitudes were measured via an Implicit Association Test (IAT), and their explicit racial attitudes were measured via an explicit scale. We found that Chinese adolescents and adults displayed both implicit and explicit racial biases against black people; however, they did not show implicit or explicit racial biases against white people. We also found that participants’ implicit and explicit racial biases were not affected by their age or gender.

1. Introduction

In the United States, racial bias problem is one of the biggest social problem. . For example, the past year has witnessed George Floyd’s death, shootings of Daunte Wright and many others. Not only in the US, racial bias also exists in China. For example, Chinese people regard black people as poor, dirty and danger, and regard white people as kind, wealthy and other positive traits. As reported in several news outlets, many black people in Guangdong province were expelled from their own apartment without any notice [1].

Racial bias exerts detrimental influences on various aspects at individual and institutional levels. The minority groups are suffering from unequal treatment in education, employment, medicine and many other aspects. For example, minority groups have lower call-backs in job interviews [2], higher rates of being suspected by the police [3], and more unfair treatment in public place [4].

Two forms of racial biases exist. One is explicit racial bias, a form of bias that people are aware of and are often measured via self-report. The other form of bias is often referred to as implicit bias that can’t be measured directly and is more unconscious [5].

Most of the existing literature about racial biases focused on explicit racial bias, leaving it less known about implicit racial bias. More importantly, less is known how the implicit racial bias developed with age. It was only in the past decade or so, researchers began to examine the development of implicit racial bias.

Previous research conducted in western countries has shown that implicit racial attitudes form as early as preschool age [6; 7]. Children learn implicit racial bias from the parents, daily life and other external source unconsciously [8]. These studies also found that implicit racial bias can last until high school. For example, with increased age, the implicit racial bias can also be deepened or mitigated but can’t be eliminated [9]. Even in the college and higher education degree, the implicit racial bias also exists in people’s mind [10].

Recently, evidence from non-US cultures also found similar results, such that implicit attitude toward race form as early as preschool age among Singaporeans [11] and Chinese [12]. For example, Qian et al. [13] used a preschooler-friendly Implicit Association Test and found that 3-year-old Chinese associate good attributes with own-race Chinese and bad attributes with other-race Black people.

Although there is emerging evidence about the early development of racial bias in non-US cultures, little is known about how such racial biases develop with age. Particularly, less is known about racial biases development in adolescents and adults Hence, in the present study, we aim to address this gap by sampling a group of Chinese adolescents and adults. We assessed their implicit and explicit biases toward two outgroup members, black people and white people. We are particularly interested in whether participants’ age and gender would affect the development of implicit and explicit racial biases.

Based on previous work, we have three hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that implicit and explicit racial biases would exist among Chinese adolescents and adults. We also hypothesized that implicit and explicit racial biases would be affected by participants’ age and gender. Lastly, we hypothesized that implicit and explicit racial biases would be disassociated, based on previous evidence in children [13] and adults [6].

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

The sample consisted of 60 Chinese participants (26 males, 34 females). Age ranges from 16 to 21 years including both adolescents and adults. Adolescents were recruited from a high school in a median-sized city in China. They were all Han-China, which represent 99% of the local population, and from middle-class families (middle class family with median educational level parents). Adults participants were recruited from a university in the same city. All of participants signed the consent prior to the participation of the experiment and volunteered to participate the experiment.

2.2 Procedures

Participants first finished an Implicit Association Test [14]. Participants’ racial attitudes towards Blacks were assessed by a Black-Chinese IAT, and their racial attitudes towards Whites were assessed by a Chinese-White IAT.

After the IAT, participants were asked 5 questions about their explicit attitude of black people and white people. The first question is which race would you prefer to make friend, black persons or white persons. The second question is a scale question about the degree of liking of black person from 1 to 7. The third question is also a scale question about the degree of liking of white person from 1 to 7. And the fourth and fifth question will be the similar scale question, but they measure the degree of liking of participants’ parents toward black and white persons.

After completing the implicit and explicit assessments, participants were asked to fill out a demographic questionnaire.

2.3 Measurement

Implicit Association Test (IAT). IAT is a method to measure implicit attitudes people are less aware of [14]. IAT assesses how quickly positive or negative stereotype (e.g. athletic, dirty) are associated with certain some concepts (e.g. African American, LGBT). The main principle of IAT is that people make faster and accurate response when the stereotype closely associated with the concepts. We used two race IATs, White-Chinese IAT and Black-Chinese IAT, to assess Chinese participants’ implicit racial bias. For example, in the Black-Chinese IAT, it includes 5 blocks. In the first block, the participants need to sort of some pictures or words of concepts. For example, if the categories are white (left) and black (right), and there is a black picture showing on the screen, the participants need to press one of the right keys to sort the picture to the right. And the second part needs the participants to sort some words of evaluation. For example, if the categories are positive (left) and negative (right), and there is a word of sad showing on the screen, the participants need to press one of the right keys to sort the word to the right. In the third part of the IAT, the words or pictures of concepts and evaluation will be mixed randomly and the participants will need to sort the mixed categories, hence the left side may shows positive and white, and the right side shows negative and black. Because the mixture is random, some participants may see the left side is positive and black, and the right side shows negative and white. In the fourth part, the categories will switch side, the black shows on left side and the white shows on the right side. In the final part, the mixture will be different from the third part, if in third part, positive and white are in same category, now the positive will combine with black [14].

We included 10 pictures of black person (5 males and 5 females) and 10 pictures of Chinese persons (5 males and 5 females) for the Chinese-Black IAT, and 10 pictures of White persons and 10 pictures of Chinese persons for the White-Chinese IAT. The category of black persons is on the left side, and the participants are asked to press “A” key to sort the pictures to the left category. The category of white persons is on the right side, and the participants are asked to press “L” key to sort the pictures to the right category. In this first block, there are 20 trials for the participants to practice. In the second block, the participants are asked to sort some words about attitude, positive (happy, love, great, good, joyful) and negative (worry, terrible, horrible, failure, fear). The positive category is on the left and negative category is on the right. In this block, we also design 20 trials for practice. In the third block, the combination of negative/ black persons (left) and positive/ white persons (right) is showed in the screen which needs the participants to sort. This block is a practice trial which contain 20 trials. In the fourth block, the participants are asked to do the same test as the third block, but this time will be the test block which contain 40 trials. And in the fifth block, the categories of white persons and black persons will be change side. The category of white persons will place on the left side and the category of black persons will place on the black side. This block is also a practice block which contain 20 trails. In the sixth block, the combination will change to black persons/ positive (right) and white persons/ negative (left). In order to improve validity, this block will contain 20 trials for the participants to practice. In the seventh block, this block will be the test block for testing the reaction time of new combination, and in this block, there are 40 trials.

Explicit Racial Bias Test. Explicit racial bias was measured with a forced-choice task in which children were asked to report their preference for interacting with own- race versus other-race individuals [13].

3. Results

3.1 Implicit Racial Attitudes

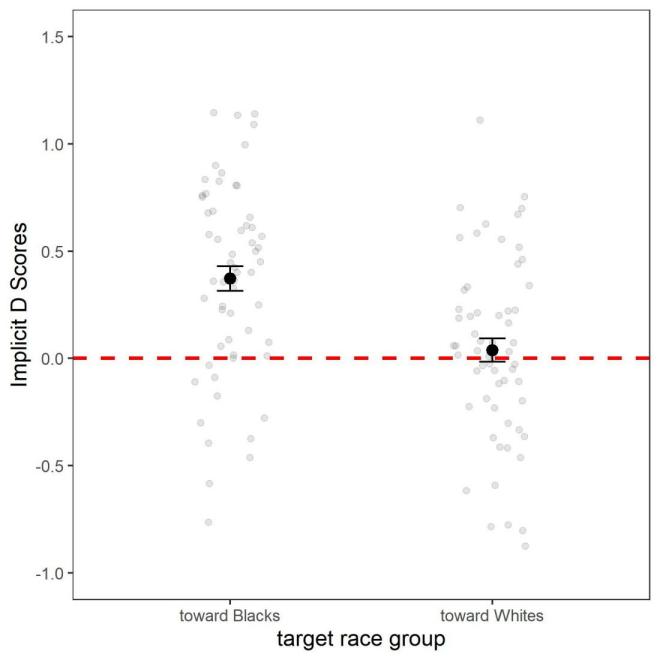

Implicit racial attitude towards Black people. To examine whether Chinese people hold negative implicit racial attitudes toward Blacks, we conducted a one sample t test. We found that Chinese people’s (M = 0.37, SD = 0.45) implicit D scores were significantly above zero, t(59) = 6.46, p < 0.001 (see Figure 1-left panel). These results suggest that Chinese people have negative implicit biases toward black people.

Figure 1: implicit D score toward Blacks and Whites among Chinese participants. Red dotted line represents no bias. Any scores above zero indicate implicit pro-own/anti-other biases. Error bars represent standard errors.

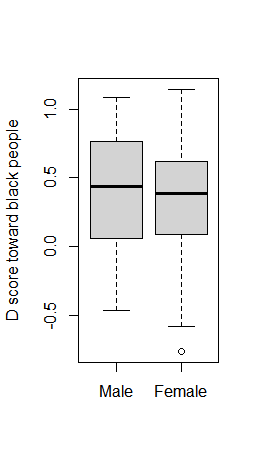

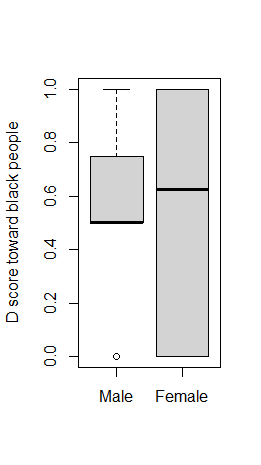

An independent-sample t test was conducted and found that there is no significant main effect of gender, t(58) = 0.28, p =0.78. These results suggest that Chinese males and females show similar levels of implicit attitude toward black people.

Figure 2: Implicit D scores toward Blacks among Chinese males and females

We also conducted an independent-sample t test and found no significant main effect of Chinese people’s age on the implicit attitude toward black people, t(58) = -0.16, p = 0.87. These results suggest that Chinese adolescent and adults show similar levels of implicit attitude toward black people.

Implicit racial attitudes toward White people. Similar analyses were conducted to examine whether Chinese people hold negative implicit racial attitudes toward Whites. We found that Chinese people’s implicit D scores were not significantly above zero, M = 0.04, SD = 0.42, t(59) = 0.71, p =0.48 (see Figure 1 – right panel), suggesting that unlike strong implicit anti-Black bias, Chinese people hold neutral racial attitudes toward White people.

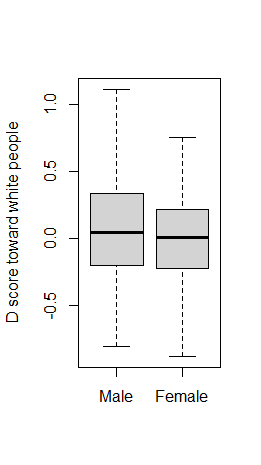

An independent-sample t test was conducted and found that there is no significant main effect of gender, t(58) = 0.70, p = 0.48. These results suggest that Chinese males and females show similar levels of implicit attitude toward white people.

Figure 3: Implicit D scores toward Whites among Chinese males and females

We also conducted an independent-sample t test and found no significant main effect of Chinese people’s age on the implicit attitude toward white people, t(58) = -0.60, p = 0.55. These results suggest that Chinese adolescent and adults show similar levels of implicit attitude toward white people.

3.2 Explicit Racial Attitude

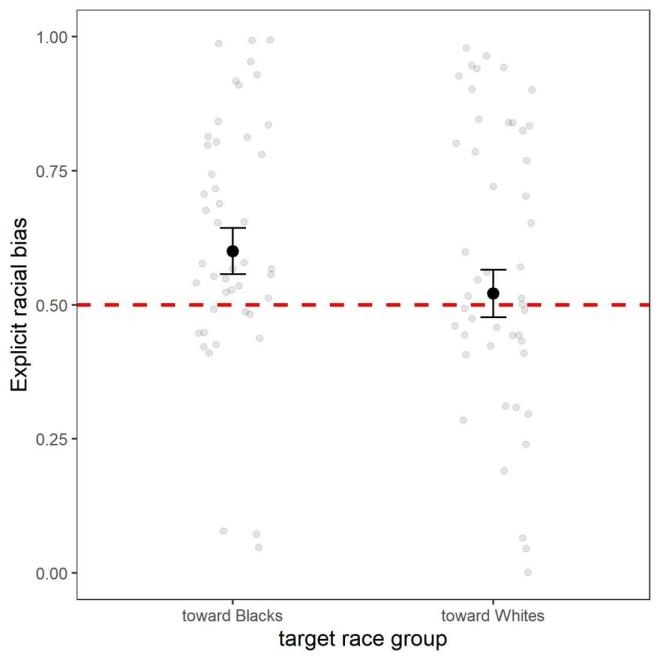

Explicit racial attitudes toward Blacks. To examine whether Chinese people hold negative explicit racial attitudes toward Blacks, we conducted a one sample t test. We found that Chinese people’s (M = 0.60, SD = 0.33) explicit D scores were significantly above 0.5, t(59) = 2.33, p <0.05 (see figure4 left panel). These results suggest that Chinese people have explicit negative bias toward black people.

Figure 4: explicit racial biases towards Blacks and Whites among Chinese participants. Red dotted line represents no bias. Any scores above .5 indicate explicit pro-own/anti-other biases. Error bars represent standard errors.

An independent-sample t test was conducted and found that there is no significant main effect of gender, t(58) = 0.90, p =0.37. These results suggest that Chinese males and females show similar levels of explicit attitude toward black people.

Figure 5: implicit racial attitudes toward black people between male and female participants.

We also conducted an independent-sample t test and found no significant main effect of Chinese people’s age on the implicit attitude toward black people, t(58) = -0.08, p = 0.93. These results suggest that Chinese adolescent and adults show similar levels of explicit attitude toward black people.

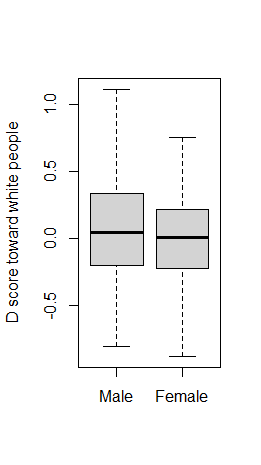

Explicit racial attitudes towards Whites. To examine whether Chinese people hold negative explicit racial attitudes toward Whites, we conducted a one sample t test. We found that Chinese people’s (M = 0.60, SD = 0.33) explicit D scores were not significantly above 0.5, t(59) = 0.71, p = 0.48 (see Figure 4 right panel). These results suggest that Chinese people have no explicit negative bias toward white people.

An independent-sample t test was conducted and found that there is no significant main effect of gender, t(58) = 1.30, p = 0.20. These results suggest that Chinese males and females show similar levels of explicit attitude toward white people.

Figure 6: Different gender’s score toward white people.

We also conducted an independent-sample t test and found no significant main effect of Chinese people’s age on the implicit attitude toward black people, t(58) = 0.82, p = 0.41. These results suggest that Chinese adolescent and adults show similar levels of explicit attitude toward black people.

3.3 Correlations between Implicit and Explicit Racial Attitudes

We also conducted Pearson correlational analysis to examine the relationship between the implicit attitude and explicit attitude. The results showed that there is no correlations between each implicit and explicit racial attitudes. More details were showed in Table 1.

Table 1. Correlations between implicit anti-Black, anti-White and explicit anti-Black and anti-White biases.

Implicit Racial toward Black people | Implicit Racial toward White people | Explicit Racial toward Black people | Explicit Racial toward White people | |

Implicit Racial toward Black people | / | |||

Implicit Racial toward White people | r(58) = 0.16 p =0.21 | / | ||

Explicit Racial toward Black people | r(58) = 0.05 p =0.72 | r(58) = -0.04 p =0.74 | / | |

Explicit Racial toward Black people | r(58) =0.06 p =0.67 | r(58) = -0.17 p =0.18 | r(58) = 0.23 p =0.08 | / |

4. Discussion

The present study investigated age-related changes in Chinese people’s implicit and explicit racial biases toward Black and White people. Specifically, we examined whether Chinese teenagers and adults show implicit and explicit racial biases against Black people and White people, and whether age and education will affect their implicit and explicit biases. We found that implicit and explicit biases against black people group was evident in Chinese teenagers and adults, and that both age groups showed similar levels of implicit racial biases. We also found that explicit and implicit anti-White biases was not evident for Chinese teenagers and adults.

Our results that implicit biases against black people was evident in Chinese teenagers and adults was consistent with our hypothesis. This result is consistent with previous work suggesting that White American adults showed implicit racial biases against Blacks commonly exist among adults in the U.S [6; 10; 15]. The result is also consistent with some other western literature suggesting White adults showed implicit anti-Black and anti-Asian, or anti-Latino biases [16]. Besides, it is also consistent with evidence obtained in non-Western cultures, such as Hong Kong and Japan [7; 13].

According to the previous research, implicit racial bias exists as young as age 3 years [7; 11; 13]. With the growth of educational degree, the implicit racial biases can be affected by many factors, some people may relieve their implicit biases, but some other people’s implicit biases may be aggravated [9]. In the previous research, some results also showed that the hugest effect factor to reduce implicit racial biases is the parents’ effect in the early childhood which showed that the implicit racial biases may not be affected by educational degree [8]. The previous results were also similar to our results. Adolescents displayed similar levels as adults, suggesting that implicit racial bias already exists in full form in adolescents. This is also consistent with previous work with adolescents.

Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that teenagers and adults showed similar levels of implicit racial biases [7]. And this result is also consistent with previous work suggesting that there is no age difference in implicit racial bias across life spans [11].

We also found out there is no significant main effect of Chinese people’s gender on the explicit and implicit biases against Blacks and Whites. Our results also showed that there was no correlational relationship between each implicit racial bias and explicit racial bias.

4.1 Limitations and Future Research

There are a few limitations to consider. First, there were only 60 participants in our experiment, and all of them were in the same city of China. Therefore, the results might not be generalizable to participants in other cultures or other cities in China. For the future research, we need to collect more data in Chinese located in different cities and also include a wider range of age groups. Another limitation is that that we did not include a comprehensive set of questions asking participants ‘socioeconomic factors. For example, previous work by Qian et al. [13] suggest that relative social status between own- versus other-race groups affect the development of racial biases. Future research could develop more fine-grained questions to assess social status, such as education, family income. Another important future research is to design longitudinal experiments to track the same age group for a longer period of time, to examine whether there are implicit and explicit racial biases toward other race group. Finally, future research are needed to include other population groups in different cultures, particularly cultures that vary in racial diversity because we know interracial contact affect the level of racial biases.

References

[1]. China: Covid-19 Discrimination Against Africans. (2020, October 28). Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/05/china-covid-19-discrimination-against-africans

[2]. Minorities Who “Whiten” Job Resumes Get More Interviews. (2017, May 17). HBS Working Knowledge. https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/minorities-who-whiten-job-resumes-get-more-interviews

[3]. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Education, D. O. B. A. S. S. A., Justice, C. O. L. A., Committee on Proactive Policing: Effects on Crime, Communities, and Civil Liberties, Majmundar, M. K., & Weisburd, D. (2018). Proactive Policing: Effects on Crime and Communities (National Academies Press of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine Consensus Study Report). National Academies Press.

[4]. Brenan, B. M. (2021, June 22). New Highs Say Black People Treated Less Fairly in Daily Life. Gallup.Com. https://news.gallup.com/poll/317564/new-highs-say-black-people-treated-less-fairly-daily-life.aspx

[5]. Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review, 102(1), 4–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.102.1.4

[6]. Baron, A. S., & Banaji, M. R. (2006). The Development of Implicit Attitudes. Evidence of Race Evaluations From Ages 6 and 10 and Adulthood. Psychological Science, 17(1), 53–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01664.x

[7]. Dunham, Y., Chen, E. E., & Banaji, M. R. (2013). Two Signatures of Implicit Intergroup Attitudes. Psychological Science, 24(6), 860–868. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612463081

[8]. Scott, K. E., Shutts, K., & Devine, P. G. (2020). Parents’ Expectations for and Reactions to Children’s Racial Biases. Child Development, 91(3), 769–783. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13231

[9]. Currarini, S., Jackson, M. O., & Pin, P. (2010). Identifying the roles of race-based choice and chance in high school friendship network formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(11), 4857–4861. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0911793107

[10]. Beattie, G., Cohen, D., & McGuire, L. (2013). An exploration of possible unconscious ethnic biases in higher education: The role of implicit attitudes on selection for university posts. Semiotica, 2013(197). https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2013-0087

[11]. Setoh, P., Lee, K. J. J., Zhang, L., Qian, M. K., Quinn, P. C., Heyman, G. D., & Lee, K. (2019). Racial Categorization Predicts Implicit Racial Bias in Preschool Children. Child Development, 90(1), 162–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12851

[12]. Qian, M., Heyman, G. D., Quinn, P. C., Messi, F. A., Fu, G., & Lee, K. (2021). Age-related differences in implicit and explicit racial biases in Cameroonians. Developmental Psychology, 57(3), 386–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001149

[13]. Qian, M. K., Heyman, G. D., Quinn, P. C., Messi, F. A., Fu, G., & Lee, K. (2016). Implicit Racial Biases in Preschool Children and Adults From Asia and Africa. Child Development, 87(1), 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12442

[14]. Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197

[15]. Dunham, Y., Baron, A. S., & Banaji, M. R. (2008). The development of implicit intergroup cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(7), 248–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2008.04.006

[16]. Lane, K. A., Kang, J., & Banaji, M. R. (2007). Implicit Social Cognition and Law. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 3(1), 427–451. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.lawsocsci.3.081806.112748

Cite this article

Zhang,C. (2021). The Development of Racial Attitudes among Chinese Adolescents and Adults. Communications in Humanities Research,1,55-63.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Educational Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries (ICEIPI 2021), Part 2

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. China: Covid-19 Discrimination Against Africans. (2020, October 28). Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/05/china-covid-19-discrimination-against-africans

[2]. Minorities Who “Whiten” Job Resumes Get More Interviews. (2017, May 17). HBS Working Knowledge. https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/minorities-who-whiten-job-resumes-get-more-interviews

[3]. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Education, D. O. B. A. S. S. A., Justice, C. O. L. A., Committee on Proactive Policing: Effects on Crime, Communities, and Civil Liberties, Majmundar, M. K., & Weisburd, D. (2018). Proactive Policing: Effects on Crime and Communities (National Academies Press of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine Consensus Study Report). National Academies Press.

[4]. Brenan, B. M. (2021, June 22). New Highs Say Black People Treated Less Fairly in Daily Life. Gallup.Com. https://news.gallup.com/poll/317564/new-highs-say-black-people-treated-less-fairly-daily-life.aspx

[5]. Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review, 102(1), 4–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.102.1.4

[6]. Baron, A. S., & Banaji, M. R. (2006). The Development of Implicit Attitudes. Evidence of Race Evaluations From Ages 6 and 10 and Adulthood. Psychological Science, 17(1), 53–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01664.x

[7]. Dunham, Y., Chen, E. E., & Banaji, M. R. (2013). Two Signatures of Implicit Intergroup Attitudes. Psychological Science, 24(6), 860–868. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612463081

[8]. Scott, K. E., Shutts, K., & Devine, P. G. (2020). Parents’ Expectations for and Reactions to Children’s Racial Biases. Child Development, 91(3), 769–783. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13231

[9]. Currarini, S., Jackson, M. O., & Pin, P. (2010). Identifying the roles of race-based choice and chance in high school friendship network formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(11), 4857–4861. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0911793107

[10]. Beattie, G., Cohen, D., & McGuire, L. (2013). An exploration of possible unconscious ethnic biases in higher education: The role of implicit attitudes on selection for university posts. Semiotica, 2013(197). https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2013-0087

[11]. Setoh, P., Lee, K. J. J., Zhang, L., Qian, M. K., Quinn, P. C., Heyman, G. D., & Lee, K. (2019). Racial Categorization Predicts Implicit Racial Bias in Preschool Children. Child Development, 90(1), 162–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12851

[12]. Qian, M., Heyman, G. D., Quinn, P. C., Messi, F. A., Fu, G., & Lee, K. (2021). Age-related differences in implicit and explicit racial biases in Cameroonians. Developmental Psychology, 57(3), 386–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001149

[13]. Qian, M. K., Heyman, G. D., Quinn, P. C., Messi, F. A., Fu, G., & Lee, K. (2016). Implicit Racial Biases in Preschool Children and Adults From Asia and Africa. Child Development, 87(1), 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12442

[14]. Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197

[15]. Dunham, Y., Baron, A. S., & Banaji, M. R. (2008). The development of implicit intergroup cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(7), 248–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2008.04.006

[16]. Lane, K. A., Kang, J., & Banaji, M. R. (2007). Implicit Social Cognition and Law. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 3(1), 427–451. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.lawsocsci.3.081806.112748