1. Introduction

The increasing significance of globalization, along with the rise of information technology, has underscored the importance of English as a second language for learners worldwide [1]. As English learners develop, their opportunities to receive feedback from more experienced speakers is key to their development [2]. Whether delivered by teachers, peers, or through personal experiences, feedback is recognized as a fundamental component of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learning and is considered one of the most influential factors in this process [2-4]. As an increasing number of English learners are enrolling in online English learning experiences, the field’s knowledge about the role of feedback is only beginning to enter the digital realm [5]. Aside from the existing discussed role of teacher feedback in online teaching, which primarily focuses on confirming answers or correcting errors, other functions of teacher feedback have been little explored in the context of online classrooms [6]. Furthermore, as more research has focused on the ESL language acquisition framework, some scholars suggest that feedback from teachers can influence ESL learners' language motivation [7]. The traditional framework of teacher feedback emphasizes error correction as a central mechanism, which is considered to lead students to adopt defensive strategies during the learning process, thereby hindering second language performance [8]. However, such a new motivational standpoint extends beyond traditional frameworks. Unlike the unidirectional approach of traditional feedback, the new perspective views motivation as dynamic and evolving, highlighting the need for feedback that supports and enhances learners' intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

Grounded in sociocultural perspectives that view learners as active participants in the learning process, contemporary researchers consider learning motivation as something that is not fixed but rather evolves over time and adapts to changing environments [9]. While this new, dynamic learning theory has been considered within traditional offline ESL classrooms, how feedback in online teaching environments can effectively stimulate learners' intrinsic and extrinsic motivation remains systematically under-explored. Therefore, this highlights the need for further research to understand how teacher feedback can be optimized to enhance ESL learners' motivation and success in virtual learning environments.

This research aims to fill this critical gap by conducting a systematic literature review to uncover how teachers’ corrective feedback during online classes can improve motivation among ESL learners in higher education. Such an analysis will provide us with insights into not only the basic effects of teachers' feedback in L2 learning but also how this feedback can be integrated into broader educational strategies to foster inclusive and effective language learning environments for ESL students.

To this end, this research asks:

1. What research exists about corrective feedback during online higher education ESL classes?

2. To what extent and in what ways does the literature engage with the concept of motivation?

2. Theoretical Framework

The research questions are grounded in theoretical perspectives on motivation that highlight the dynamic nature of language learning motivation and the multifaceted impact of feedback. These perspectives are crucial for understanding how different types of feedback can influence ESL learners' motivation in an online higher education context. In the following sections, this paper will unpack these perspectives and illustrate how they have guided this study.

2.1. Motivation

Motivation in second language acquisition (SLA) is dynamic and evolving and can change over time, as suggested by Henry, Davydenko, and Dörnyei [9]. They propose that language learning motivation can undergo intense and enduring periods, known as directed motivational currents, which significantly affect learners' engagement and persistence. This dynamic view of motivation aligns with the idea that motivation is not fixed but fluctuates based on various internal and external factors. This work considers how an external factor, corrective feedback from teachers, can influence such dynamic motivation. For many years, researchers have known that corrective feedback, which involves error correction, can have dual effects on learners Krashen [8]. On one hand, it can positively impact learners by helping them understand and correct their mistakes, thereby reinforcing their learning. On the other hand, it can also induce anxiety and fear of making mistakes, potentially reducing their motivation to learn. This two-sided characteristic highlights the need for a balance of corrective feedback in the language learning process to maintain and increase learner motivation without eliciting negative emotional responses among ESLs.

2.2. Feedback

Feedback, defined as specific information provided by teachers regarding learners' performance and highlighting strengths and areas for improvement, is considered one of the most powerful influences on SLA [10]. The significance of feedback necessitates a thorough examination of its various dimensions to fully understand its impact. Feedback can be categorized based on its content and provider. In this proposal, the focus is on teacher-provided feedback specifically related to English language learning. This focus is essential because students benefit from the convenience, high quality, and content-focused nature of online teacher feedback (OTF), compared to other types of feedback such as peer feedback and computer-mediated feedback, especially in higher education setting [11-14]. Furthermore, the effectiveness of feedback also depends on its timing, with immediate feedback acting as reinforcement and enhancing competence, while delayed feedback allows for reflection and supports learning autonomy [15,16]. There is curiosity about how different types of feedback affect ESL learners' motivation. By analyzing these feedback types and their effects, this research aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of how to optimize teacher feedback in online learning environments.

3. Method and Data Sources

3.1. Literature Search

A comprehensive search in the EBSCO database is initiated in this systematic literature review, following a strategic combination of keywords and subject headings relevant to the research, as detailed in Table 1. This approach was designed to capture relevant literature by using Boolean operator “OR” to connect keywords and "AND" was used to combine different subject classification. The search included manuscripts published before July 16, 2024, and identified 611 relevant studies. All studies were imported into the systematic review software, Covidence, for further processing.

Table 1: Examples of search terms used in EBSCO Database.

Search Term Category (Joined with AND) | Search Terms in Abstract (Joined with OR) |

Corrective feedback | corrective feedback*, error correction*, feedback mechanisms*, feedback strategies*, feedback efficacy*, corrective measures*, instructor feedback*, |

ESL learner | ESL learner*, English as a Second Language*, second language learner*, L2 learner*, non-native English speaker*, language acquisition*, ESL student*, ESL education*, language learning*, ESL instruction*, ESL pedagogy*, EFL (English as a Foreign Language), TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages), CELTA (qualification for teaching English as a foreign language), |

Online classes | virtual classes*, virtual learning*, virtual instruction*, digital classes*, online classes*, digital education*, online learning*, e-learning*, online education*, internet-based learning*, online instruction*, online platform*, high-tech*, remote education*, distance learning*, |

3.2. Literature Screening

In the screening phase, Covidence automatically detected and removed 50 duplicate entries, and an additional two duplicates were manually excluded. Two coders screened the remaining 559 studies by examining their titles and abstracts excluding articles using following exclusion criteria:

1. Studies must be about feedback from teachers, not learners.

2. Only studies focusing on students in higher education were included, excluding those about secondary students, teachers, or parents.

3. The studies needed to focus on online learning environments.

4. Only studies concerning ESL learners were considered; those involving native English speakers were excluded.

5. Studies must be specifically about English language learning; for instance, ESL learning in scientific subjects was excluded.

6. Eligible studies had to be written either in English or Chinese.

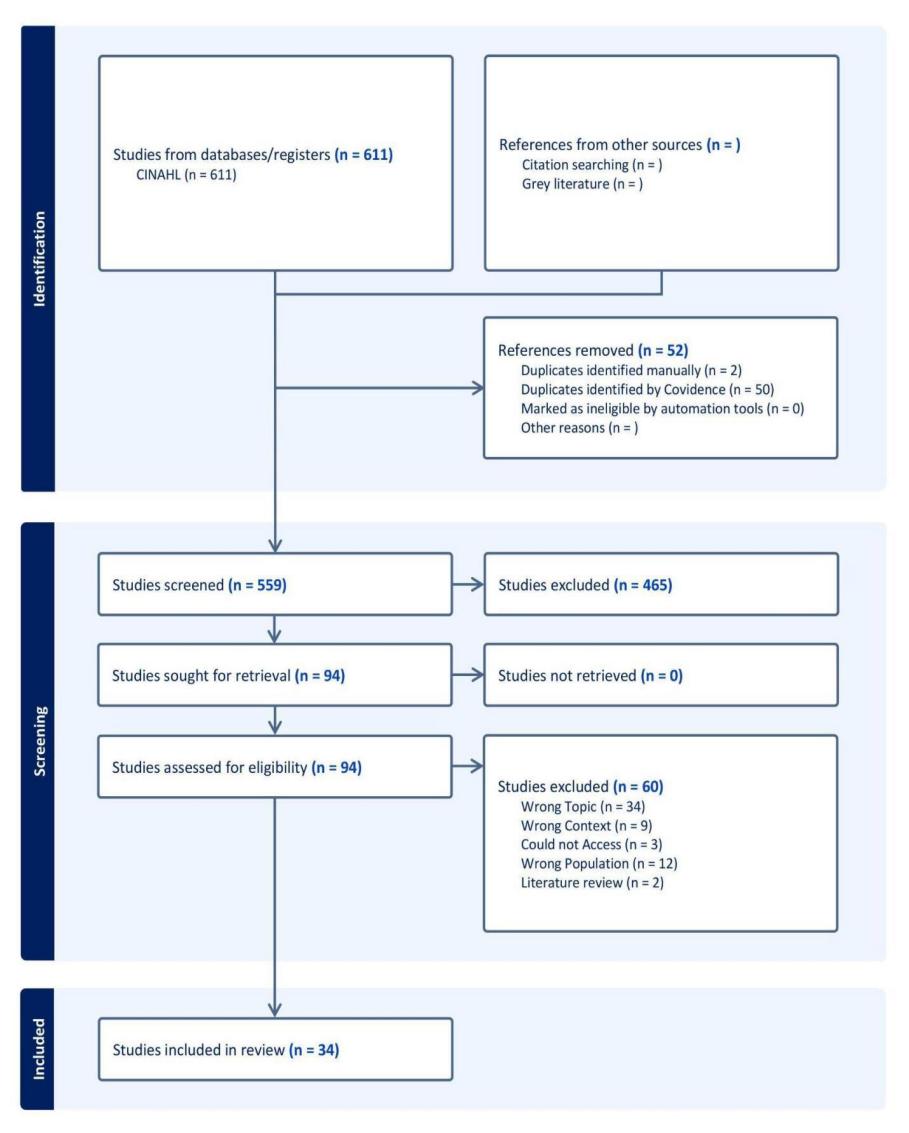

All disagreements between coders were resolved through discussion and the initial screening process led to the exclusion of 465 articles, leaving 94 articles for full-text assessment, as depicted in the PRISMA flow diagram (see Figure 1). Full texts were retrieved from various databases and screened by the same two coders who again discussed all conflicts before resolving disagreements. Additional 60 studies were excluded for inconsistencies with the listed criteria mentioned above, such as targeting factors unrelated to teacher feedback, the wrong population, or the wrong context. Ultimately, 34 studies suitable for in-depth analysis and further exploration are identified (see table 2).

Figure 1: PRISMA diagram of the identification process through Covidence.

Table 2: Included Literature and Study Characteristics.

Study | Investigates Motivation with Teacher Feedback | Feedback Types |

Functions of Teacher Echoing in an EFL Class Delivered via Videoconferencing | No | Immediate |

A Comparison of the Effects of Classroom and Multi-User Virtual Environments on the Perceived Speaking Anxiety of Adult Post-Secondary English Language Learners | No | Immediate |

Using 'Writeabout as a Tool for' Online Writing and Feedback | No | Immediate |

An Examination of Students' Attitude towards the Use of Google Classroom in Preparatory Year English Program | No | Immediate |

Implementation of Assessment for Learning in Online EFL Writing Class: A Case of Novice Undergraduate Teachers | No | Delayed |

Using Turnitin to Provide Feedback on L2 Writers' Texts | No | Delayed |

Using Online Annotations to Support Error Correction and Corrective Feedback | No | Delayed |

Using an e-Portfolio System to Improve the Academic Writing Performance of ESL Students | No | Delayed |

Students' Perceptions and Learning Outcomes of Online Writing Using Discussion Boards | No | Delayed |

E-Feedback as a Scaffolding Teaching Strategy in the Online Language Classroom | No | Delayed |

Blended Approach to Learning and Practising English Grammar with Technical and Foreign Language University Students: Comparative Study | No | Delayed |

Video Chat vs. Face-to-Face Recasts, Learners' Interpretations and L2 Development: A Case of Persian EFL Learners | No | Delayed |

Formative Multimodal E-Feedback in Second Language Writing Virtual Learning Spaces | No | Delayed |

CoI-Based Teaching Practices to Promote EFL Learners' Online Discussion in China's Blended Learning Context | No | Immediate&Delayed |

Blended Learning Using Video-Based Blogs: Public Speaking for English as a Second Language Students | No | Immediate&Delayed |

Pre-Service Language Teachers' Online Written Corrective Feedback Preferences and Timing of Feedback in Computer-Supported L2 Grammar Instruction | No | Immediate&Delayed |

A Discussion on How Teachers Assess What Foreign Language Students Learn in Telecollaboration | No | Immediate&Delayed |

'Ok I Think I Was Totally Wrong :) New Try!': Language Learning in WhatsApp through the Provision of Delayed Corrective Feedback Provided during and after Task Performance | No | Immediate&Delayed |

Best Practices Teaching Adult English as a Second Language in the Virtual Classroom | No | Not Mentioned |

Automated Feedback and Teacher Feedback: Writing Achievement in Learning English as a Foreign Language at a Distance | No | Not Mentioned |

The Effects of Online Feedback on ESL/EFL Writing: A Meta-Analysis | No | Not Mentioned |

Second Language Teacher Cognition Development in an Online L2 Pronunciation Pedagogy Course: A Quasi-Experimental Study | No | Not Mentioned |

Guided Online Coaching for Teachers of Emergent Bilinguals in a TESOL Practicum Course during COVID-19 | No | Not Mentioned |

Investigating Learner Preferences for Written Corrective Feedback in a Thai Higher Education Context | No | Not Mentioned |

The Perception of Female Saudi English Students of the Relative Value of Writing Feedback through ?Conferencing | Yes | Immediate |

Effects of English Proficiency on Motivational Regulation in a Videoconference-Based EFL Speaking Class | Yes | Immediate |

Students' and Tutors' Perceptions of Feedback on Academic Essays in an Open and Distance Learning Context | Yes | Delayed |

Exploring Learners' Grammatical Development in Mobile Assisted Language Learning | Yes | Delayed |

Video Feedback and Foreign Language Anxiety in Online Pronunciation Tasks | Yes | Delayed |

Using Screencast Video Feedback in the 21st Century EFL Writing Class | Yes | Delayed |

College Students' Perception of E-Feedback: A Grounded Theory Perspective | Yes | Immediate&Delayed |

Second Language Learners' and Teachers' Perceptions of Delayed Immediate Corrective Feedback in an Asynchronous Online Setting: An Exploratory Study | Yes | Immediate&Delayed |

Online Discussion: Mission Impossible or Possible for Low-Achieving EFL Students | Yes | Immediate&Delayed |

Motivational Regulation for Learning English Writing through Zoom in an English-Medium Instruction Context | Yes | Immediate&Delayed |

3.3. Literature Analysis

After screening the studies, the extraction phase of analysis is conducted with 34 suitable studies (see table 2). The data were coded in multiple steps to analyze how relevant literature discusses online teacher feedback in relation to higher education ESL learners engage with the concept of motivation. Firstly, it was verified whether study connects teacher feedback with ESL learners’ motivation. Subsequently, based on the studies’ treatment of the relationship between teacher feedback and motivational aspects, the studies were categorized into three groups: (1) investigates teacher feedback and its impact on ESL learners' motivation, (2) investigates motivation in ESL contexts other than teacher feedback, and (3) investigates teacher feedback in ESL without addressing motivation (see Table 3). Such categories are designed based on whether the study of online teacher feedback focused on motivation. In the next phase of analysis, the studies were sorted according to the second criterion, which was the timeliness of the feedback. In this phase, the studies were divided into '(1) immediate feedback, (2) delayed feedback, (3) both immediate and delayed feedback, and (4) not mentioned' (see Table 4). The categories were configured in this manner in alignment with the observed preference for immediate feedback in students' perceptions during screening [17].

Table 3: Categorization and Distribution of the Reviewed Literature as it Relates to Motivation.

Category of analysis | Definition | Example | Distribution of articles |

Investigates Teacher Feedback and Its Impact on ESL Learners' Motivation | Research in this category examines motivation in ESL contexts, and specifically in relation to teacher feedback. It includes studies that investigate how and to what extent teacher feedback influences learners’ motivation and autonomy in learning English as a second language. | An example of this type of study is by Kim[18], which finds out that the feedback offered by teacher online is helping learners to complete every single task by way of encouraging or constructive feedback. This research falls under the category 'Investigates Teacher Feedback and Its Impact on ESL Learners' Motivation', as it analyzes how teacher feedback affects ESL learners’ motivation. | 29.41% of articles |

Investigates Motivation in ESL Contexts Other Than Teacher Feedback | Research in this category examines motivation in ESL Settings but does not specifically deal with teacher feedback. It includes examining how various factors, such as platforms, online learning tools, and automated feedback systems, affect learners' motivation and autonomy in learning English as a second language. | An example of this type of study is by Taskiran[19], which investigates the impact of automated and teacher feedback on academic writing achievement for ESL learners in an online learning context. This research falls under the category 'Investigates Motivation in ESL Contexts Other Than Teacher Feedback,'as it only addresses how automated feedback might contribute to learner motivation and autonomy in ESL settings. | 38.24% of articles |

Investigates Teacher Feedback in ESL Without Addressing Motivation | Research in this category investigates teacher corrective feedback in ESL learning without specifically addressing its impact on student motivation. Research may understand the influence of feedback towards ESL language learning from other theoretical perspectives such as cognitive, constructive or theory of lifelong learning. | An example of such research is Alharbi [20], which examines electronic feedback as a scaffolding teaching strategy in an online language classroom. This study falls under the category of "investigating the role of teacher corrective feedback in ESL without addressing motivation" because it only explores how electronic feedback can facilitate language learning through a constructivist approach, without considering ESL learners' motivation. | 32.35% of articles |

Table 4: Categorization of Teacher Feedback according to timing.

Category of analysis | Definition | Example | Distribution of articles |

Immediate Teacher Feedback | Feedback given almost immediately after a student completes a task or during an online teaching session. This type of feedback aims at quickly correcting or improving the student's performance, addressing aspects such as grammatical structures, verbal expressions, or other specific issues. | An example of this type of study is by Rassaei[21], which explores the difference between corrective feedback via video chat and via offline conversation that results in learners’ different performance. This research falls under the category 'Immediate Teacher Feedback', as it provides immediate feedback during the video chat or face-to-face condition. | 17.65% of articles |

Delayed Teacher Feedback | Delayed feedback is provided after the student has completed the task and often offers more comprehensive and detailed evaluations than immediate feedback. Teachers may utilize various formats for delayed feedback, such as video or digital corrective feedback uploaded to online platforms. | An example of such research is Chokwe [22], which investigated ESL students' and tutors' perceptions of feedback on academic articles in an online learning environment. This study falls under the category of "delayed feedback," in that teachers will respond to later posts created by academic English writing students. | 38.24% of articles |

Both Immediate and Delayed Feedback | Such studies evaluate both immediate and delayed feedback. They examine how the integration of these feedback types improves timeliness and thoroughness, benefiting English learners. | An example of this type of study is by Xiaoxing [23], which focuses on how teacher’s practices within the Community of Inquiry model (CoI) impact EFL learners’ motivation in the online discussion forums. This study falls under the category' Both Immediate and Delayed Feedback', as the CoI prompts immediate feedback in class, and delayed but frequent feedback in the after-class phase. | 26.47% of articles |

Not Mentioned | Research in this category examines teachers’ feedback to ESL learners, while the timeliness of feedback in it could not be identified. They encompass a broader analysis of education, such as the influence on fostering the ESL learners’ motivation for lifelong learning. | An example of this type of study is by Chung [24], which emphasizes that teachers should provide constructive feedback to motivate ESL learners’ lifelong learning journey. It also mentions 'the lack of non-verbal cues' problem existing in online feedback. This study falls under the category 'Not Mentioned', as the timing of feedback delivery in it is undefined. | 17.64% of articles |

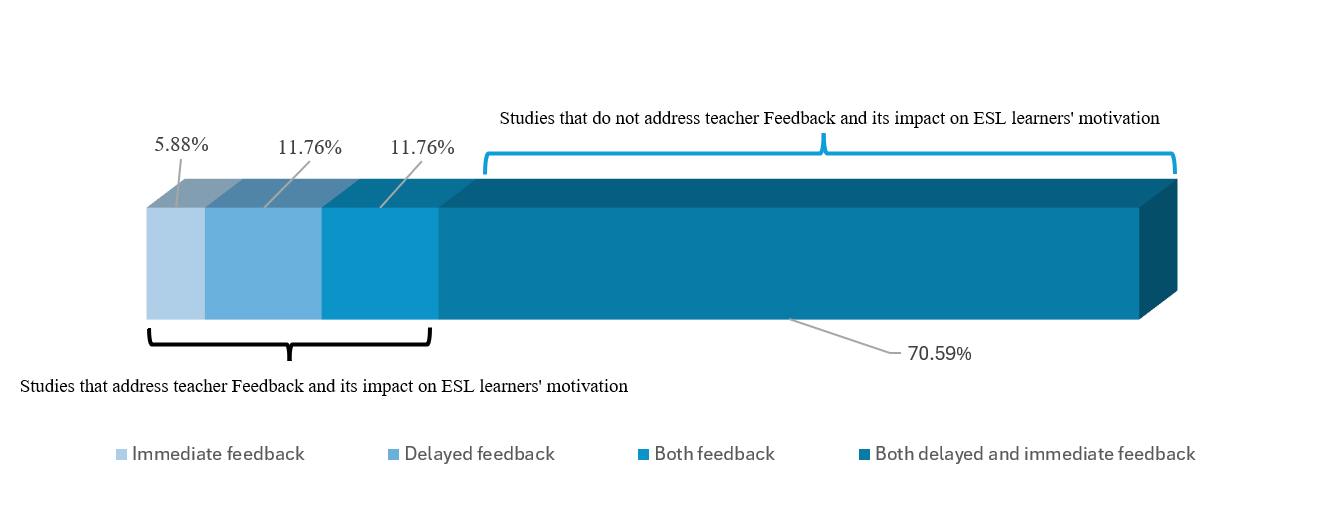

After the completion of coding, the studies were categorized twice using two distinct criteria, resulting in two separate classifications. Then, the numbers of studies were quantified and these numbers were converted into percentages later. Finally, a chart that relied on these data is produced as shown in Figure 2 and described below.

Figure 2: Distribution of Articles Investigating the Impact of Teacher Feedback on ESL Learners’ Motivation by Types of Feedback Timing.

4. Results

The interest of this paper lies in examining how existing research on teacher feedback in online courses focuses on motivation. First, the reviewed literature is categorized concerning motivation. It was discovered that in about one-third of the literature (32.35%) English online teaching was studied but learner motivation was not mentioned or investigated at all. Another significant proportion (38.24%) engaged with the motivation of ESL students as it related to topics other than teacher feedback, and less than one third of the research (29.41%) investigated teacher feedback and its impact on ESL learners' motivation (see Table 3). Additionally, even among the small proportion of studies that investigated both teacher feedback and learner motivation, most studies discussed only students' subjective perceptions of their motivation to learn English. They did not explore the detailed mechanisms of how the interaction between teacher feedback and motivation could be implemented in teachers’ pedagogies. This lack of detailed exploration leaves a significant gap in understanding how feedback can effectively enhance motivation. Secondly, because the research is clear that for feedback to be effective, its timing should be considered, this work categorized feedback into immediate feedback and delayed feedback for analysis. The results showed that, among the remaining literature, most discussions focused on the impact of teachers' delayed feedback on student motivation. Few studies investigated immediate feedback, which accounted for only 17.65% of the articles (see Table 4). This result highlights a significant gap that future researchers need to address, as immediate feedback is perceived by students as the most effective form of learning support. Students consistently report that immediate feedback supports them to assess the accuracy of language expressions, grammar structure, and to solidify their knowledge more effectively than delayed feedback [25,26]. Additionally, teachers who strive to provide feedback as promptly as possible often achieve a better motivational effect compared to delayed feedback [27].

While the broader research is clear about immediate feedback’s importance to learner outcomes and motivations, among the 34 studies that focus on online learning, only 6 in total focused on immediate feedback (see Figure 2). Moreover, these studies predominantly emphasized comparisons between immediate and delayed feedback, with conclusions often based on student questionnaires and classroom observations, lacking a comprehensive discussion solely on immediate feedback in student learning. This indicates a need for further enhancement in the credibility and completeness of these studies. Intriguingly, there are only 2 comprehensive studies summarizing the relationship between immediate teacher feedback and students’ motivation [17,28].

Although the importance of teachers' immediate feedback in promoting student motivation has garnered attention for researchers, existing research in this area focuses almost exclusively on in-person classrooms overlooking immediate feedback and motivation in online contexts. It is hoped that this comprehensive and systematic study on the relationship between immediate feedback and motivation in online contexts offers the field important information about where gaps exist and what research is needed [29].

5. Conclusion

The findings regarding the existing research online teacher feedback and ESL learners’ motivation in the online classroom highlights a critical gap in the existing literature. The current research tends to focus on teacher feedback within in-person traditional classroom contexts and models. Moreover, investigating teacher corrective feedback in ESL learning often fails to specifically address its impact on student motivation. This observed inconsistencies in the implementation of teacher feedback across various contexts indicate that existing research may fall short in facilitating the transition to digital classrooms. This inadequacy not only continues to perpetuate the long-standing gap between theory and practice but also fails to address the real practical needs of students for effective online feedback. Additionally, the limited existing research often relies on a narrow scope, overlooking the systematic dynamics of immediate feedback in promoting motivation. This leaves a gap in the field’s understanding of how different types of teacher feedback affect ESL learners' language motivation in online environments.

It is hoped that future research will investigate the multifaceted effects of teacher feedback methods on ESL learners’ motivation across the updating online context and supplemented by diverse educational theories to achieve better applicability. By suggesting ways that the field might broaden the epistemological landscape of existing research findings of this paper point to ways that the research might broaden its grounding perspectives and assumptions, contributing to more effective and inclusive virtual learning environments. Additionally, there are numerous new potentials for researchers and practitioners to advance their development of pedagogical supports for online teaching, particularly in relation to immediate feedback and other feedback methods. It is hoped that the exploration of this under-researched area will serve as a crucial steppingstone and inspire future scholars to achieve more significant advancements.

Acknowledgement

Tianhao Jin, Yi Fan, Ziqi Ren, Yicheng Wang and Xiyu Zhang contributed equally to this work. Based on alphabetical ordering by surnames, the authors are listed, with shared first authorship.

References

[1]. Shih, R. C. (2010). Blended learning using video-based blogs: Public speaking for English as a second language students. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 26 (6). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1016

[2]. Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77 (1), 81-112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

[3]. Pachuashvili, N. (2024). Using screencast video feedback in the 21st century EFL writing class. IAFOR Journal of Education, 12 (1), 225-242.

[4]. Wiggins, G. (1993). Assessing student performance. Jossey-Bass.

[5]. Grant, S., & Clerehan, R. (2011). Finding the discipline: Assessing student activity in Second Life. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 27 (5). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.868

[6]. Demirkol, T. (2022). Functions of teacher echoing in an EFL class delivered via videoconferencing. Online Submission.

[7]. Dörnyei, Z. (1998). Motivation in second and foreign language learning. Language Teaching, 31 (3), 117-135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026144480001315X

[8]. Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Pergamon Press.

[9]. Henry, A., Davydenko, S., & Dörnyei, Z. (2015). The anatomy of directed motivational currents: Exploring intense and enduring periods of L2 motivation. The Modern Language Journal, 99 (2), 329-345. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12219

[10]. Lipnevich, A. A., & Panadero, E. (2021). A review of feedback models and theories: Descriptions, definitions, and conclusions. Frontiers in Education, 6, Article 720195. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.720195

[11]. Ding, S. L., & Chew, E. (2019). Thy word is a lamp unto my feet: A study via metaphoric perceptions on how online feedback benefited Chinese learners. Educational Technology Research and Development, 67 (6), 1561-1582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-019-09709-4

[12]. Lv, X., Ren, W., & Xie, Y. (2021). The effects of online feedback on ESL/EFL writing: A meta-analysis. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 30(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00555-5

[13]. McCabe, J., Doerflinger, A., & Fox, R. (2011). Student and faculty perceptions of E-feedback. Teaching of Psychology, 38, 173–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628311418505

[14]. Ene, E., & Upton, T. A. (2018). Synchronous and asynchronous teacher electronic feedback and learner uptake in ESL composition. Journal of Second Language Writing, 41, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2018.09.001

[15]. Lowenthal, P. R., Borup, J., West, R. E., & Archambault, L. (2020). Thinking beyond Zoom: Using asynchronous video to maintain connection and engagement during distance learning. Journal of Online Learning Research, 6 (1), 7-26. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v21i4.4562

[16]. Johnson, L., Adams Becker, S., Estrada, V., & Freeman, A. (2019). NMC horizon report: 2019 higher education edition. EDUCAUSE.

[17]. Murphy, B., Mackay, J., & Tragant, E. (2023). ‘Ok, I think I was totally wrong :) New try!’: Language learning in WhatsApp through the provision of delayed corrective feedback provided during and after task performance. Language Learning Journal, 51 (4), 491-508. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2021.1886372

[18]. Kim, J., & Kweon, S. O. (2023). Effects of English proficiency on motivational regulation in a videoconference-based EFL speaking class. Education and Information Technologies, 28(7), 8401-8422.

[19]. Taskıran, A., & Goksel, N. (2022). Automated feedback and teacher feedback: Writing achievement in learning English as a foreign language at a distance. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 23(2), 120-139.

[20]. Alharbi, W. (2017). E-feedback as a scaffolding teaching strategy in the online language classroom. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 46(2), 239-251.

[21]. Rassaei, E. (2017). Video chat vs. face-to-face recasts, learners’ interpretations and L2 development: A case of Persian EFL learners. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 30(1-2), 133-148.

[22]. Chokwe, J. M. (2015). Students' and tutors' perceptions of feedback on academic essays in an open and distance learning context. Open Praxis, 7(1), 39-56.

[23]. Xiaoxing, L., & Deris, F. D. (2022). CoI-Based Teaching Practices to Promote EFL Learners' Online Discussion in China's Blended Learning Context. Asian Journal of University Education, 18(2), 477-488.

[24]. Chung, H. (2022). Best practices teaching adult English as a second language in the virtual classroom. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2022(175-176), 45-57.

[25]. Lu, X., Wang, W., Motz, B. A., Ye, W., & Heffernan, N. T. (2023). Immediate text-based feedback timing on foreign language online assignments: How immediate should immediate feedback be? Computers and Education Open, 5, Article 100148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2023.100148

[26]. Kiliçkaya, F. (2022). Pre-service language teachers’ online written corrective feedback preferences and timing of feedback in computer-supported L2 grammar instruction. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35 (5-6), 542-559. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2021.1952253

[27]. ]Canals, L., Granena, G., Yilmaz, Y., & Malicka, A. (2020). Second language learners’ and teachers’ perceptions of delayed immediate corrective feedback in an asynchronous online setting: An exploratory study. TESL Canada Journal, 37 (2), 181-209. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v37i2.1340

[28]. Cavalari, S. M. S. (2019). A discussion on how teachers assess what foreign language students learn in telecollaboration. In Telecollaboration and virtual exchange across disciplines: In service of social inclusion and global citizenship (pp. 73).

[29]. Peck, L., & Kavanagh, S. S. (2024). Learning to give feedback to student writers: A systematic review of research on field-based experiences for pre-service writing teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 144, 104602.

Cite this article

Jin,T.;Fan,Y.;Ren,Z.;Wang,Y.;Zhang,X. (2025). Teacher Feedback in Online English Language Learning: A Systematic Literature Review. Communications in Humanities Research,55,196-207.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Shih, R. C. (2010). Blended learning using video-based blogs: Public speaking for English as a second language students. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 26 (6). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1016

[2]. Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77 (1), 81-112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

[3]. Pachuashvili, N. (2024). Using screencast video feedback in the 21st century EFL writing class. IAFOR Journal of Education, 12 (1), 225-242.

[4]. Wiggins, G. (1993). Assessing student performance. Jossey-Bass.

[5]. Grant, S., & Clerehan, R. (2011). Finding the discipline: Assessing student activity in Second Life. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 27 (5). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.868

[6]. Demirkol, T. (2022). Functions of teacher echoing in an EFL class delivered via videoconferencing. Online Submission.

[7]. Dörnyei, Z. (1998). Motivation in second and foreign language learning. Language Teaching, 31 (3), 117-135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026144480001315X

[8]. Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Pergamon Press.

[9]. Henry, A., Davydenko, S., & Dörnyei, Z. (2015). The anatomy of directed motivational currents: Exploring intense and enduring periods of L2 motivation. The Modern Language Journal, 99 (2), 329-345. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12219

[10]. Lipnevich, A. A., & Panadero, E. (2021). A review of feedback models and theories: Descriptions, definitions, and conclusions. Frontiers in Education, 6, Article 720195. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.720195

[11]. Ding, S. L., & Chew, E. (2019). Thy word is a lamp unto my feet: A study via metaphoric perceptions on how online feedback benefited Chinese learners. Educational Technology Research and Development, 67 (6), 1561-1582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-019-09709-4

[12]. Lv, X., Ren, W., & Xie, Y. (2021). The effects of online feedback on ESL/EFL writing: A meta-analysis. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 30(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00555-5

[13]. McCabe, J., Doerflinger, A., & Fox, R. (2011). Student and faculty perceptions of E-feedback. Teaching of Psychology, 38, 173–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628311418505

[14]. Ene, E., & Upton, T. A. (2018). Synchronous and asynchronous teacher electronic feedback and learner uptake in ESL composition. Journal of Second Language Writing, 41, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2018.09.001

[15]. Lowenthal, P. R., Borup, J., West, R. E., & Archambault, L. (2020). Thinking beyond Zoom: Using asynchronous video to maintain connection and engagement during distance learning. Journal of Online Learning Research, 6 (1), 7-26. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v21i4.4562

[16]. Johnson, L., Adams Becker, S., Estrada, V., & Freeman, A. (2019). NMC horizon report: 2019 higher education edition. EDUCAUSE.

[17]. Murphy, B., Mackay, J., & Tragant, E. (2023). ‘Ok, I think I was totally wrong :) New try!’: Language learning in WhatsApp through the provision of delayed corrective feedback provided during and after task performance. Language Learning Journal, 51 (4), 491-508. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2021.1886372

[18]. Kim, J., & Kweon, S. O. (2023). Effects of English proficiency on motivational regulation in a videoconference-based EFL speaking class. Education and Information Technologies, 28(7), 8401-8422.

[19]. Taskıran, A., & Goksel, N. (2022). Automated feedback and teacher feedback: Writing achievement in learning English as a foreign language at a distance. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 23(2), 120-139.

[20]. Alharbi, W. (2017). E-feedback as a scaffolding teaching strategy in the online language classroom. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 46(2), 239-251.

[21]. Rassaei, E. (2017). Video chat vs. face-to-face recasts, learners’ interpretations and L2 development: A case of Persian EFL learners. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 30(1-2), 133-148.

[22]. Chokwe, J. M. (2015). Students' and tutors' perceptions of feedback on academic essays in an open and distance learning context. Open Praxis, 7(1), 39-56.

[23]. Xiaoxing, L., & Deris, F. D. (2022). CoI-Based Teaching Practices to Promote EFL Learners' Online Discussion in China's Blended Learning Context. Asian Journal of University Education, 18(2), 477-488.

[24]. Chung, H. (2022). Best practices teaching adult English as a second language in the virtual classroom. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2022(175-176), 45-57.

[25]. Lu, X., Wang, W., Motz, B. A., Ye, W., & Heffernan, N. T. (2023). Immediate text-based feedback timing on foreign language online assignments: How immediate should immediate feedback be? Computers and Education Open, 5, Article 100148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2023.100148

[26]. Kiliçkaya, F. (2022). Pre-service language teachers’ online written corrective feedback preferences and timing of feedback in computer-supported L2 grammar instruction. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35 (5-6), 542-559. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2021.1952253

[27]. ]Canals, L., Granena, G., Yilmaz, Y., & Malicka, A. (2020). Second language learners’ and teachers’ perceptions of delayed immediate corrective feedback in an asynchronous online setting: An exploratory study. TESL Canada Journal, 37 (2), 181-209. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v37i2.1340

[28]. Cavalari, S. M. S. (2019). A discussion on how teachers assess what foreign language students learn in telecollaboration. In Telecollaboration and virtual exchange across disciplines: In service of social inclusion and global citizenship (pp. 73).

[29]. Peck, L., & Kavanagh, S. S. (2024). Learning to give feedback to student writers: A systematic review of research on field-based experiences for pre-service writing teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 144, 104602.