1. Introduction

Social-emotional learning is defined by five categories: self-awareness, self-management, responsible decision-making, relationship skills, and social awareness. Students who develop self-awareness will understand who they are [1]. Students who develop self-management will be able to solve problems, plan actions, and make decisions [2]. Responsible decision-making means that students will know how to behave, act, and make choices in various situations [3]. Relationship skills refer to the ways in which students connect with one another [4]. Students who have social awareness are able to understand others' feelings [5]. Psychological barriers can arise in some students due to defensiveness, fear, imposter syndrome, low self-perception, low self-efficacy, low self-esteem, lack of confidence, and other factors. Low socioeconomic status (SES) is associated with a group of people who experience low income, inequality, financial insecurity, etc. Students from low-SES families often do not receive the same level of education as those from high-SES families and are raised in different environments. Due to the economic gap, students may develop psychological barriers. Therefore, we need to apply social-emotional learning methods to help students develop the skills to manage their emotions when facing different environments and interacting with diverse people.

This paper aims to acknowledge the heightened appreciation for SEL’s capacity to foster comprehensive student growth; it becomes imperative to delve into how this approach can alleviate the specific obstacles confronted by students from low socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds. Understanding this intersection is key to harnessing SEL’s potential for empowering these students and fostering their holistic development.

To this end, our research asks: To what extent does the existing literature discuss the impact of SEL on reducing psychological barriers among students with a low socioeconomic background? This question guides our analysis of the literature, highlighting gaps in research. Our findings will contribute to the discourse on SEL and inform future research and educational practices aimed at enhancing the well-being and academic success of all students, regardless of their socioeconomic background.

2. Theoretical framework

Our analysis draws on several educational theories to examine how Social Emotional Learning (SEL) can reduce psychological barriers for low-SES students. Specifically, we focus on cognitive constructivism, behaviorism, and sociocultural theory, which provide a comprehensive lens through which SEL’s impact can be understood.

As originally conceptualized by Piaget and Vygotsky [6,7], these theories recognize learning as an active process shaped by both internal cognitive mechanisms and external social interactions. In this framework, SEL serves as a tool that bridges cognitive, emotional, and social development, especially for students facing heightened socio-economic challenges. For low-SES students, psychological barriers such as low self-esteem heightened stress, and feelings of exclusion can impede learning. These theories suggest that SEL can address such barriers by fostering both emotional regulation and social connectedness.

2.1. Cognitive constructivist perspective

Cognitive constructivism posits that learners construct knowledge through their experiences and interactions with the environment [7]. In the context of SEL, this theory suggests that low-SES students benefit from learning environments that promote self-awareness and self-management. By building on prior experiences and internalizing new coping strategies, these students can gradually reduce negative cognitive patterns, such as stress-induced avoidance, which serve as psychological barriers to learning. SEL programs that emphasize metacognitive skills, emotional reflection, and personal goal-setting align with cognitive constructivist principles, offering pathways to self-empowerment for low-SES students.

2.2. Behaviorist perspective

The behaviorist approach, often associated with Skinner, emphasizes the modification of behavior through reinforcement and conditioning [8]. In the case of SEL, behaviorist theory explains how consistent reinforcement of positive social behaviors—such as cooperation, respect, and empathy—can help reduce disruptive tendencies often seen in students facing emotional and psychological stress. For low-SES students who may struggle with externalizing behaviors as a response to socio-economic challenges, SEL’s structured behavioral interventions can promote classroom engagement and reduce negative emotional responses.

2.3. Sociocultural theory

Vygotsky's sociocultural theory highlights the central role of social interaction in cognitive development [6]. For low-SES students, who often face marginalization or cultural identity challenges, SEL rooted in sociocultural theory can create inclusive learning environments. By fostering social connections and promoting empathy and collaboration among students from diverse backgrounds, SEL programs can alleviate feelings of isolation and exclusion. This promotes a sense of belonging and reduces psychological barriers related to identity and social marginalization, which are common among low-SES students.

Grounded in these theoretical perspectives, our review examines how SEL interventions, when implemented across various school settings, can significantly reduce the emotional and psychological challenges faced by low-SES students, allowing them to better engage in the learning process.

3. Methodology

3.1. Literature search

EBSCO was used as the database to conduct a comprehensive literature search for the review. All potentially relevant articles are considered by constructing categories of keywords and subject headings for the three key terms of the research question—social-emotional learning, low economic status, and psychological barriers. Details are demonstrated in Table 1. The three search categories were each connected by the Boolean operator “AND”, and the search terms within each category were separated by the Boolean operator “OR”. Terms related to social-emotional learning and low economic status were set to be searched within the title and abstract, and terms related to psychological barriers were searched in the full text. The search covered all literature published before August 18, 2024, and found a total number of 380 articles, which were uploaded to Covidence for screening.

Table 1: Search terms used in EBSCO database

Search Term Category Joined | Search Terms in Abstract (Joined with OR) with AND |

Social Emotional Learning | "social-emotional learning*" OR "social emotional learning*" OR "social and emotional learning*" OR "SEL" OR "self-management*" OR "self-awareness*" OR "responsible decision making" OR "relationship skill*" OR "social awareness*" OR "self-management*" OR "self-awareness*" OR "responsible decision making*" OR "relationship skill*" OR "social awareness*" |

Low Socioeconomic-status | "low socioeconomic-status*" OR "low socioeconomic status*" OR "low SES*" OR "economic bracket" OR "low status*" OR "low income*" OR "Poverty" OR "Income inequality" OR "Social class" OR "Socioeconomic disparity" OR "Disadvantaged communities" OR "Social mobility" OR "Marginalized groups" OR "Financial insecurity" OR "Education gap" OR "Unemployment*" OR "Underemployment*" OR "Food insecurity" OR "Housing instability" OR "Healthcare disparities" OR "Limited access to resources" |

Psychological Barriers | "Psychological barriers to communication" OR "frame of reference" OR "defensiveness and fear" OR "risk and protective factors" OR "imposter syndrome" OR "premature evaluation" OR "self-perception" OR "self-efficacy" OR "self-esteem" OR "self-image" OR "confidence*" |

3.2. Literature screening

Upon uploading the articles to Covidence for screening, the system automatically removed 14 duplicate texts. The remaining 366 articles were screened by five group members and selected for full-text review by following the exclusion criteria written below:

1. Studies must be about any aspect of students of low socioeconomic status.

2. Studies reveal the effects of social-emotional learning on individual students only. Studies that go beyond the individual scope will be excluded.

3. Only studies that include any strategies of social-emotional learning should be included. Studies that focus on other teaching methodologies should be excluded.

4. Studies must reveal the effects of social-emotional learning on students’ psychology only.

5. Studies must be in English or Chinese.

Each study was reviewed by two screeners, and the same two screeners would discuss the relevance of the study with each other when a conflict arose between their votes. Of the 366 articles, 349 were found to be irrelevant to the research question. The 17 remaining studies are uploaded onto Covidence from various databases like EBSCO and JSTOR for further full-text screening.

3.3. Literature analysis

After full-text screening, our group came up with a set of hypotheses:

6. The SEL strategies are implemented in classroom settings, and most strategies are incorporated with other subjects.

7. The articles focus more on the behaviors students show after engaging in social-emotional learning, but the psychological reasons behind those behaviors are not fully investigated. Only a few articles mentioned the effect of SEL on the students’ awareness of cultural identity.

8. The methodology used to examine the effect of SEL on students is mostly quantitative. Only a few methods used are qualitative.

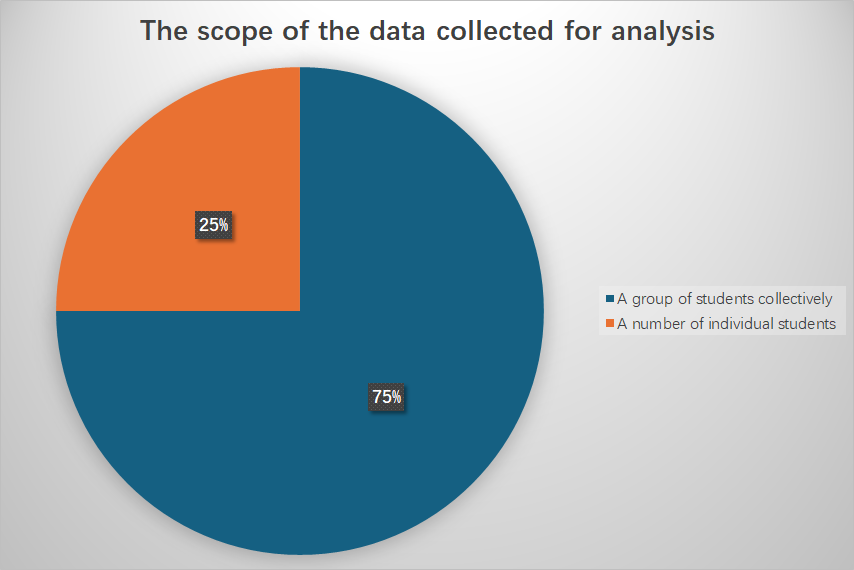

9. Most articles focus on the effect of SEL on a group of students. Only a few articles show the effect of SEL on students at individual levels.

To test our hypothesis, we set up a code extraction table. The data were coded in multiple steps so that we can find the trend of the current studies that examine the effect of SEL on students with low SES. Firstly, we examine whether the implementation of SEL strategies is being incorporated into other subjects or not (See Table 2). Second, we examine whether the participants of a study are a group of students collectively or a number of individual students (See Table 3). Third, we examine whether the study uses quantitative data or qualitative data (See Table 4). Fourth, we examine the study’s outcome (See Table 5). The outcomes are categorized into six categories: (1) the student's behaviors on academic subjects, (2) the student's behaviors other than behaviors on academic subjects, (3) the student's thinking, (4) the students' sense of identity, (5) students' relationships with others, and (6) the overall classroom atmosphere. Fifth, we examine the study’s theoretical framework (See Table 6). The theoretical frameworks are categorized into five categories: (1) Behaviorist, (2) Socioculturalism, (3) Mixed, (4) Pure Cognitivism, and/or Cognitive Constructivist. The tables attached to this paper show our definition and examples for each category.

Table 2: Where does the study take place

Category of analysis | Definition | Example | Distribution of articles | Number of articles |

Inside of the classroom and being incorporated into other subjects | During the implementation of the strategy, a group of students are inside the same room working on the same goal under the guidance of a tutor, and the goal includes both social-emotional learning and other learning goals, such as learning English or Math. | An example of this study is [9]. The methods used in this study include facilitating classroom conversations on social justice, student’s families, student’s personal feelings toward a personal event, and personal loss during Literature and Humanities classes. | 75% of articles | 6 |

Inside of the classroom as an individual subject | During the implementation of the strategy, a group of students are inside a same room working on a same goal under the guidance of a tutor, and the goal is to implement social-emotional learning. | An example of this study is [10]. During the intervention stage of this study, the teachers are required to use e Preschool PATHS curriculum [11] in the classroom of a kindergarten. This curriculum covers the topics of prosocial skills, emotional understanding, self-control, and social problem-solving. | 25% of articles | 2 |

Table 3: The scope of the data collected for analysis

Category of analysis | Definition | Example | Distribution of articles | Number of articles |

A group of students collectively | All the students use the same set of criteria to contribute to the data. | An example of this study is [12]. In this study, the researchers created a likert-scale questionnaire for the participants. All participants are asked to finish the same questionnaire before and after the study. | 75% of articles | 6 |

A number of individual students | The students and teachers who participate in the study will contribute the data using different sets of criteria. | An example of this study is [9]. In this study, Antonio collected data from his classroom observations, conversations with teachers and students, field notes, and teacher journals. | 25% of articles | 2 |

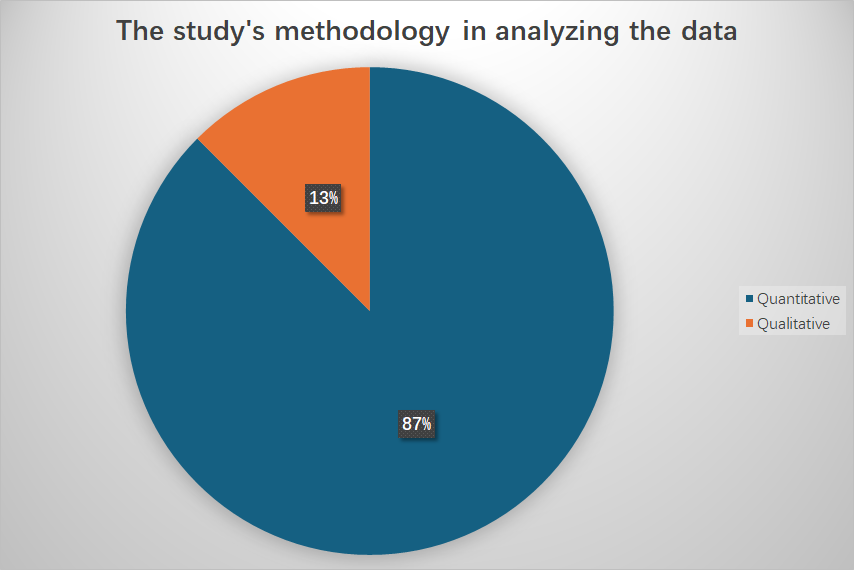

Table 4: The study’s methodology in analyzing the data

Category of analysis | Definition | Example | Distribution of articles | Number of articles |

Quantitative | These kinds of studies collect numerical data. Usually, students are asked to do a survey before the implementation of SEL, so that the researchers could get the baseline data. Students are asked to do a survey at the end of the experiment, so that the researchers could get the endline data. | An example of this study is [2]. In this study, the researchers created a likert-scale questionnaire for the participants. Participants are asked to do the questionnaire before and after the study. The researchers then collected and analyzed the data on students’ self-awareness, self management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision making. | 87.5% of articles | 7 |

Qualitative | These kinds of studies collect non numerical data. | An example of this study is [9]. In this study, Antonio collected data from his classroom observations, conversations with teachers and students, field notes, and teacher journals. | 12.5% of articles | 1 |

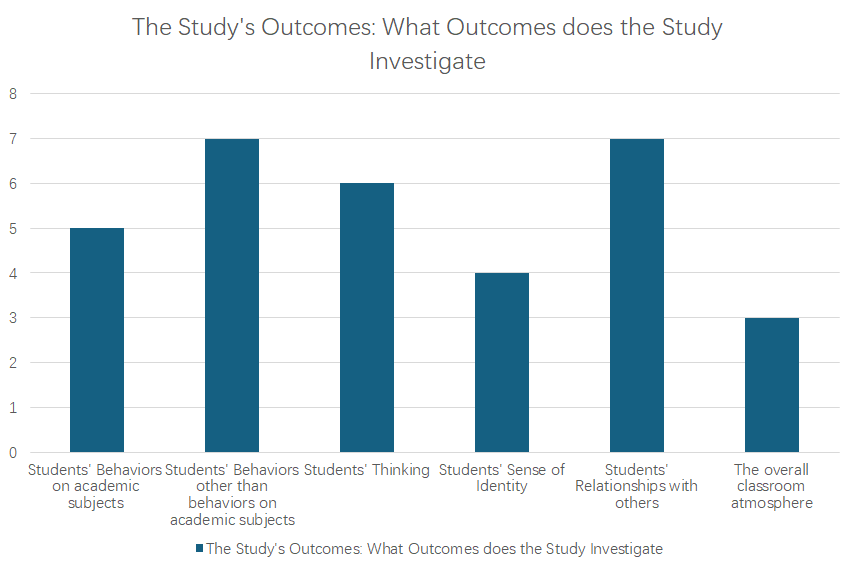

Table 5: The study’s outcomes: what outcomes does the study investigate

Category of analysis | Definition | Example | Distribution of articles | Numbers of articles |

Students' behaviors on academic subjects | An improve in the subjects related with academic performance. For example, vocabulary or grades of a specific subject. | An example of this study is [9]. This study examines student’s ability on vocabulary. | 62.5% of articles | 5 |

Students' behaviors other than behaviors on academic subjects | The teachers rate the students on their behaviors other than academic behaviors or the peers rate their classmates. | An example of this study is [13]. Teachers rate on children’s skills, knowledge, and behaviors using a likert scale. | 87.5% of articles | 7 |

Students’ thinking | Students rate themselves using questionnaires, students directly respond to interview questions, or teachers record students’ thoughts that are said by students. | An example of this study is [10]. In the study, the students rate themselves using a questionnaire that asks questions about their social emotional distress, and school bonding (E.g. one choice in the likert scale that asks school bonding is “I like my class this year”). | 75% of articles | 6 |

Students’ sense of identity | There are questions in the questionnaire or the interview for students that ask about how students view themselves. | An example of this is the study [9]. The study shows that the improve in language skills after the implementation of SEL can help students view themselves as an autonomous being and as a social being. | 50% of articles | 4 |

Students’ relationships with others | There are natural observations about the students’ interaction in school or questions in questionnaire that ask about students’ interactions with their peers. | An example of this is the study [14]. This study examines the number of good friends and bad friends that students have. | 87.5% of articles | 7 |

The overall classroom atmosphere | There are questions that asks the overall classroom environment. | An example of this is the study [15]. This study examines whether the SEL strategy promote a classroom environment that is safer, more cooperative, more predictable, and more supportive. | 37.5% of articles | 3 |

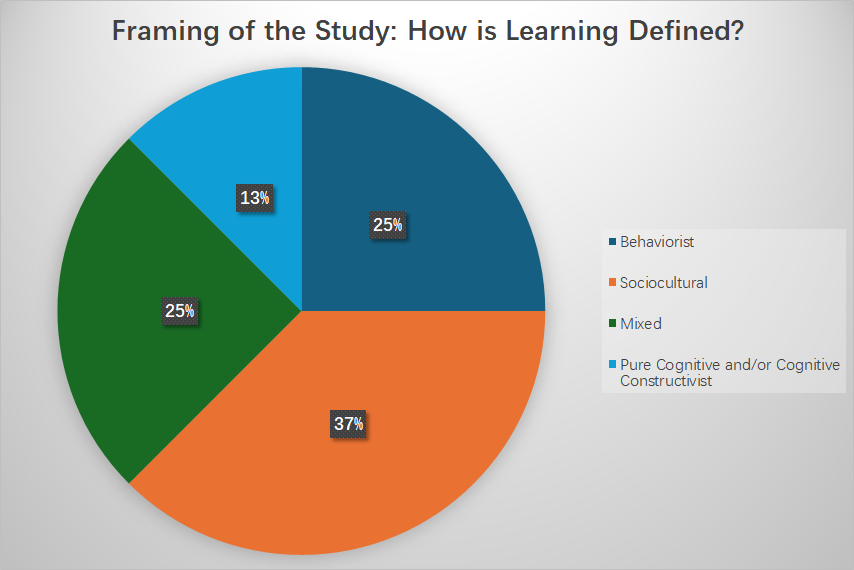

Table 6: Framing of the study: how is learning defined

Category of analysis | Definition | Example | Distribution of articles | Number of articles |

Behaviorist | Behaviorism defines learning as a change in observable behavior that occurs through the use of stimuli and responses. Learning is shaped through reinforcement and punishment without considering internal thoughts or feelings. | An example of this study is [16]. In this study, Johnson collected data from classroom observations, teacher feedback, and student behavior tracking systems. Johnson's research emphasized behaviorist approaches in SEL by using positive reinforcement techniques to encourage emotional management in low-SES students. The findings revealed that reinforcing positive emotional behaviors significantly reduced instances of disruptive conduct and increased student engagement. | 25% of articles | 2 |

Sociocultual | Sociocultural theory posits that learning is a social process deeply embedded in cultural context. Knowledge is co-constructed through interaction with others, and language and social tools are critical in learning development. | An example of this study is [17]. In this study, Garcia collected data from group discussions, peer collaboration projects, and teacher journals. Garcia’s research explored how social interactions within culturally relevant contexts enhanced low-SES students’ emotional awareness. The study highlighted how SEL in a supportive social environment helped students navigate emotional challenges by learning from their peers' cultural perspectives and experiences. | 37.5% of articles | 3 |

Mixed | This category represents articles that integrate various theoretical perspectives, such as combining behaviorist, cognitive, and sociocultural approaches to offer a more comprehensive understanding of learning. | An example of this study is [18]. In this study, Lee collected data from classroom observations, interviews with teachers and students, student performance assessments, and peer group discussions. The study utilized a combination of cognitive reflection tasks, behavioral reinforcement strategies, and collaborative social projects to assess the impact of SEL on low-SES students. This mixed approach showed improvements in both academic outcomes and social-emotional skills, such as self-regulation and peer interactions. | 25% of articles | 2 |

Pure Cognitive and/or Cognitive Constructivist | Cognitive Constructivism views learning as an active process where individuals build their own understanding by connecting new knowledge to prior experiences. It emphasizes mental processes, internal understanding, and the active role of the learner. | An example of this study is [19]. In this study, Smith collected data from student work samples, reflective journals, and interviews with teachers and students. Smith's research applied cognitive constructivist principles by focusing on how students actively constructed their understanding of emotional regulation through guided problem-solving tasks. The study showed that SEL programs framed around cognitive reflection improved students' ability to self-regulate in challenging situations. | 12.5% of articles | 1 |

4. Findings and discussions

We finally found 8 papers about this topic in the database we use. This fact implies that this topic is under-investigated. The exact percentage of those I will mention will be in tables at the end of our paper.

As hypothesized, most studies focus heavily on student behaviors but, surprisingly, rarely delve into the psychological mechanisms driving those behaviors. In our analysis, 62.5% of the studies discussed changes in students' behaviors—both academic and non-academic—while only a small portion touched on the emotional or cognitive processes (Figure 1 &2). This confirms the need for further research to examine how SEL fosters deeper psychological changes, such as building self-esteem or reducing anxiety, particularly in low-SES students.

Figure 1: Framing of the study: how is learning defined

Figure 2: The study outcomes

Moving on to the methodology, 87.5% of the research relied on quantitative approaches (Figure 3). This clear reliance on quantifiable data highlights a gap in understanding the qualitative, lived experiences of students. Only one study used qualitative methods, which limits the ability to capture more complex emotional and psychological shifts. Addressing this imbalance in future research could yield more holistic insights into SEL's impact, especially on an individual level.

Figure 3: The study’s methodology in analyzing the data

Speaking of individuals, our findings also aligned with the hypothesis that most studies focus on groups rather than individual students. In fact, 75% of the studies collected data on student groups, with only 25% focused on individual students (Figure 4). This means that the unique experiences and responses of individual students to SEL interventions are still underexplored. Research on individual-level effects would be valuable in identifying how students with different psychological barriers or socioeconomic challenges respond differently to SEL.

Figure 4: The scope of the data collected for analysis

Finally, SEL’s impact on cultural identity awareness is another area that remains underrepresented. Only 25% of the studies addressed the development of students' cultural identity, even though this is a crucial aspect of their social-emotional growth. This is particularly relevant for low-SES students, who often come from diverse cultural backgrounds. More attention to this area could significantly enhance the understanding of how SEL helps students not only manage their emotions but also strengthen their sense of self and identity.

The findings of our study are crucial because low-SES students, often exposed to poverty, abuse, and violence, are more likely to experience trauma at a young age, which leads to behavioral challenges such as refusal to participate in class or emotional outbursts. As noted in the paper "Exploring a School–University Model for Professional Development With Classroom Staff: Teaching Trauma-Informed Approaches," many classroom staff are ill-equipped to handle these behaviors and often rely on zero-tolerance policies, which may unintentionally retrigger traumatic memories for these students. Our findings show that current SEL research predominantly focuses on observable behaviors and lacks exploration of the underlying psychological mechanisms driving these behaviors. Moreover, the reliance on punitive discipline further underscores the need for trauma-informed SEL approaches that can address the unique emotional needs of low-SES students. Filling these gaps is essential for developing more effective, inclusive SEL interventions that reduce psychological barriers and promote holistic development.

5. Conclusion

Our literature review provides significant insight on the scope of research regarding social-emotional learning and its impact on students of low socio-economic backgrounds and reveals several gaps in the existing research. Research done upon this subject is very often group-centric, which means researchers are taking the average data of the entire classrooms where the majority of its students have low SES and not looking at how individual students respond to SEL in an environment with mixed SES. Consequently, these studies rely on quantitative data to communicate their findings, like test results of students before and after a SEL program. This can be problematic to provide a holistic review of the SEL approach because the lack of qualitative data taken through observation of individual students results in less research on the non-academic changes in students with low SES.

For future research, we strongly suggest a focus on the unique cognitive changes that individual low SES students experience when engaging in SEL learning, as the current research can only give a broad understanding of how classrooms as a whole perform before and after SEL interventions. The effectiveness of this teaching method cannot be determined simply through quantitative research on student academic performance because a crucial understanding of the impacts it has on students’ deeper psychological processes like mindset, self-esteem, identity, regulation and emotions comes from qualitative research [20]. Students of low-SES backgrounds are more likely to have unresolved psychological barriers towards learning, and teachers struggle to respond in a constructive and supportive way as they develop punitive disciplinary confrontations to counter negative classroom behavior [21]. When studies are unable to provide research for how the cognition of individual students changes through SEL and how it can help students thrive outside of academic settings, teachers are unable to adapt SEL approaches to their low SES students who will come from varying cultural backgrounds with different response patterns. The topic of SEL programs for students with a low SES background is under-investigated as a whole, and we urge for more research in the future to cover the different lenses of analysis on the effectiveness of SEL.

Acknowledgement

Yuping Shi, Zhaonan Yang, Jiawei Chen, Haoru Qiu, Mu Yang, and Xinyu Jiang contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors.

References

[1]. Eurich, T. (2018). What self-awareness really is (and how to cultivate it). Harvard Business Review, 4(4), 1-9.

[2]. Lorig, K. R., & Holman, H. R. (2003). Self-management education: History, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 26(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm2601_01

[3]. Zsolnai, L. (2017). Responsible decision making. Routledge.

[4]. Edition, T. (2008). Interpersonal messages: Communication and relationship skills (5th ed.). Pearson Education.

[5]. Wegner, D. M., & Giuliano, T. (1982). The forms of social awareness. In A. H. Hastorf & A. M. Isen (Eds.), Personality, roles, and social behavior (pp. 165-198). Springer New York.

[6]. Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

[7]. Piaget, J. (1970). The science of education and the psychology of the child. Orion Press. Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. Oxford University Press.

[8]. Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. Macmillan.

[9]. Antonio, D. M. S. (2018). Collaborative Action Research to Implement Social-emotional Learning in a Rural Elementary School: Helping Students Become “Little Kids With Big Words.” The Canadian Journal of Action Research, 19(2), 26–47. https://doi.org/10.33524/cjar.v19i2.384

[10]. Sanders, M. T., Welsh, J. A., Bierman, K. L., & Heinrichs, B. S. (2020). Promoting resilience: A preschool intervention enhances the adolescent adjustment of children exposed to early adversity. School Psychology, 35(5), 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000406

[11]. Domitrovich, C. E., Cortes, R. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (2007). Improving Young Children’s Social and Emotional Competence: A Randomized Trial of the Preschool “PATHS” Curriculum. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 28(2), 67–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-007-0081-0

[12]. Aradhya, A. B. S., & Parameswaran, S. (2023). Efficacy of Systemic SEL Intervention ‘acSELerate’ on Students’ SEL Development: Evidence from a Field Study. Revista Romaneasca Pentru Educatie Multidimensionala, 15(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.18662/rrem/15.2/717

[13]. Mondi, C. F., & Reynolds, A. J. (2020). Socio-Emotional Learning among Low-Income Prekindergarteners: The Roles of Individual Factors and Early Intervention. Early Education and Development, 32(3), 360–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2020.1778989

[14]. Lewis, K. M., Holloway, S. D., Bavarian, N., Silverthorn, N., DuBois, D. L., Flay, B. R., & Siebert, C. F. (2021). Effects of Positive Action in Elementary School on Student Behavioral and Social-Emotional Outcomes. The Elementary School Journal, 121(4), 635–655. https://doi.org/10.1086/714065

[15]. Torrente, C., Aber, J. L., Starkey, L., Johnston, B., Shivshanker, A., Weisenhorn, N., Annan, J., Seidman, E., Wolf, S., & Dolan, C. T. (2019). Improving Primary Education in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: End-Line Results of a Cluster-Randomized Wait-List Controlled Trial of Learning in a Healing Classroom. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 12(3), 413–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2018.1561963

[16]. Johnson, V. L., Simon, P., & Mun, E. (2013). A Peer-Led High School Transition Program Increases Graduation Rates Among Latino Males. The Journal of Educational Research, 107(3), 186–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2013.788991

[17]. Garcia, P., Sibele, N. (2021). The Consolidation of Social-emotional Learning in Primary Education. Panorama.

[18]. Lee, J., Shapiro, V. B., & Kim, B. E. (2023). Universal School-Based Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) for Diverse Student Subgroups: Implications for Enhancing Equity Through SEL. Prevention Science, 24(5), 1011–1022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-023-01552-y

[19]. Dobia, B., Parada, R. H., Roffey, S., & Smith, M. (2019). Social and emotional learning: From individual skills to class cohesion. Educational and Child Psychology, 36(2), 78–90.

[20]. Schiepe-Tiska, A., Dzhaparkulova, A., & Ziernwald, L. (2021). A mixed-methods approach to investigating social and emotional learning at schools: Teachers’ familiarity, beliefs, training, and perceived school culture. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.518634

[21]. Anderson, E., Blitz, L.V., & Saastamoinen, M. (2015). Exploring a School-University Model for Professional Development with Classroom Staff: Teaching Trauma-Informed Approaches. School Community Journal, 25, 113-134.

Cite this article

Shi,Y.;Yang,Z.;Chen,J.;Qiu,H.;Yang,M.;Jiang,X. (2025). SEL’s Impact on Reducing Psychological Barriers for Low-SES Students: Review and Future Directions. Communications in Humanities Research,55,257-268.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Eurich, T. (2018). What self-awareness really is (and how to cultivate it). Harvard Business Review, 4(4), 1-9.

[2]. Lorig, K. R., & Holman, H. R. (2003). Self-management education: History, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 26(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm2601_01

[3]. Zsolnai, L. (2017). Responsible decision making. Routledge.

[4]. Edition, T. (2008). Interpersonal messages: Communication and relationship skills (5th ed.). Pearson Education.

[5]. Wegner, D. M., & Giuliano, T. (1982). The forms of social awareness. In A. H. Hastorf & A. M. Isen (Eds.), Personality, roles, and social behavior (pp. 165-198). Springer New York.

[6]. Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

[7]. Piaget, J. (1970). The science of education and the psychology of the child. Orion Press. Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. Oxford University Press.

[8]. Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. Macmillan.

[9]. Antonio, D. M. S. (2018). Collaborative Action Research to Implement Social-emotional Learning in a Rural Elementary School: Helping Students Become “Little Kids With Big Words.” The Canadian Journal of Action Research, 19(2), 26–47. https://doi.org/10.33524/cjar.v19i2.384

[10]. Sanders, M. T., Welsh, J. A., Bierman, K. L., & Heinrichs, B. S. (2020). Promoting resilience: A preschool intervention enhances the adolescent adjustment of children exposed to early adversity. School Psychology, 35(5), 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000406

[11]. Domitrovich, C. E., Cortes, R. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (2007). Improving Young Children’s Social and Emotional Competence: A Randomized Trial of the Preschool “PATHS” Curriculum. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 28(2), 67–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-007-0081-0

[12]. Aradhya, A. B. S., & Parameswaran, S. (2023). Efficacy of Systemic SEL Intervention ‘acSELerate’ on Students’ SEL Development: Evidence from a Field Study. Revista Romaneasca Pentru Educatie Multidimensionala, 15(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.18662/rrem/15.2/717

[13]. Mondi, C. F., & Reynolds, A. J. (2020). Socio-Emotional Learning among Low-Income Prekindergarteners: The Roles of Individual Factors and Early Intervention. Early Education and Development, 32(3), 360–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2020.1778989

[14]. Lewis, K. M., Holloway, S. D., Bavarian, N., Silverthorn, N., DuBois, D. L., Flay, B. R., & Siebert, C. F. (2021). Effects of Positive Action in Elementary School on Student Behavioral and Social-Emotional Outcomes. The Elementary School Journal, 121(4), 635–655. https://doi.org/10.1086/714065

[15]. Torrente, C., Aber, J. L., Starkey, L., Johnston, B., Shivshanker, A., Weisenhorn, N., Annan, J., Seidman, E., Wolf, S., & Dolan, C. T. (2019). Improving Primary Education in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: End-Line Results of a Cluster-Randomized Wait-List Controlled Trial of Learning in a Healing Classroom. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 12(3), 413–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2018.1561963

[16]. Johnson, V. L., Simon, P., & Mun, E. (2013). A Peer-Led High School Transition Program Increases Graduation Rates Among Latino Males. The Journal of Educational Research, 107(3), 186–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2013.788991

[17]. Garcia, P., Sibele, N. (2021). The Consolidation of Social-emotional Learning in Primary Education. Panorama.

[18]. Lee, J., Shapiro, V. B., & Kim, B. E. (2023). Universal School-Based Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) for Diverse Student Subgroups: Implications for Enhancing Equity Through SEL. Prevention Science, 24(5), 1011–1022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-023-01552-y

[19]. Dobia, B., Parada, R. H., Roffey, S., & Smith, M. (2019). Social and emotional learning: From individual skills to class cohesion. Educational and Child Psychology, 36(2), 78–90.

[20]. Schiepe-Tiska, A., Dzhaparkulova, A., & Ziernwald, L. (2021). A mixed-methods approach to investigating social and emotional learning at schools: Teachers’ familiarity, beliefs, training, and perceived school culture. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.518634

[21]. Anderson, E., Blitz, L.V., & Saastamoinen, M. (2015). Exploring a School-University Model for Professional Development with Classroom Staff: Teaching Trauma-Informed Approaches. School Community Journal, 25, 113-134.