1. Introduction

Hyponymy, also known as “semantic inclusion”, is one of the key research objects in semantics. Not only does this type of relationship occur in nature, hyponymy also exists among varied words in human languages. Hyponymy consists of hypernym and hyponym, which implies a hierarchical relationship and can be divided into different levels.

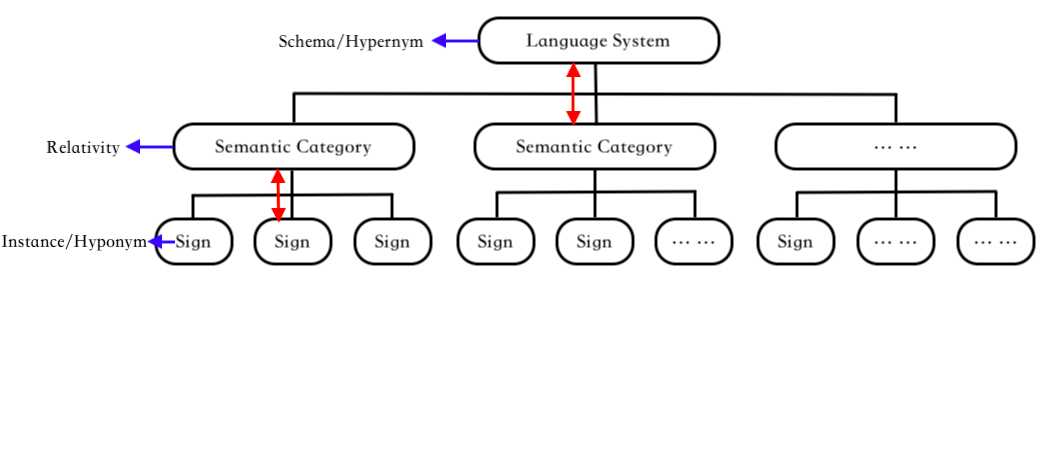

Similarities can be found in Saussure’s system-based theory, where its three terminologies “language system”, “semantic category”, and “sign” reflect a schema-instance relationship and uncover the hierarchical feature of the language system, as they are in the different levels. These similarities enable the re-explanation of hyponymy from the perspective of Saussure’s system-based theory, offering a new explanatory path for the mechanisms of hyponymy.

2. Theoretical underpinnings

2.1. The definition of hyponymy in a general sense

In linguistics, hyponymy refers to the relationship between the more general term, such as “color”, and the more specific instances of it, such as “red”. To be specific, a hyponym (from Greek hupó, “under” and ónoma, “name”) is a word or phrase whose semantic field is included within that of another word, its hypernym (from Greek hupér, “over” and ónoma, “name”) [1-3]. For example, “pigeon”, “crow”, “eagle” and “seagull” are all hyponyms of “bird” (their hypernym); which, in turn, is a hyponym of “animal”.

According to the definition of hyponymy, different words can be divided into different levels on the basis of their varied degrees of abstraction and generalization. That is to say, the more abstract a word is, the more likely that it would belong to a hypernym, and vice versa.

2.2. The understanding of Saussure’s system-based theory

System is a key notion in Saussure’s linguistics. In Saussure’s account, langue, or the language system, comprises two orders of difference: phonic and conceptual, which have the potential to combine in the making of signs [4-6]. The combining of terms from those two orders of difference is a semiotic activity. Saussure [7: 87] wrote that just as in any system of signs, the linguistic system consists of a series of differences in sounds together with differences in ideas. The differences distinguish one sign from all the others that constitute the system. It shows that the language system, two semantic categories, and signs constitute the three basic elements of Saussure’s system-based theory.

Moreover, in Saussure’s conception, the separability of those two orders of differences means that there is no fixed, univocal relation between signifier and signified in any given sign relation. Such arbitrariness can lead to the production of signs that are opposite to or different from one another during this free process of combination.

3. The current studies

The language system, semantic categories and signs, as mentioned above, constitute the three basic elements of Saussure’s system-based theory. According to the research of Zhang [8], Zhang and Zhang [9], Saussure’s language system reflects a schema-instance relationship. A clear definition of schema, instance, and their relationship have been offered by Evans and Green, where “a schema is a symbolic unit that emerges from a process of abstraction over more specific symbolic units called instances”, and “the relationship between a schema and the instances from which it emerges is the schema-instance relationship” [10: 504]. It indicates that the schema-instance relationship is hierarchical and can be divided into different levels.

In Saussure’s language system, the language system is an abstract concept towards semantic categories; and the semantic categories are abstract concepts towards signs. In other words, the schema, which is at a higher level, is both more general and more abstract; while the instance at a lower level has more delicate semantic specifications. Therefore, from the language system (top) to signs (bottom), the level of those basic elements is decreased, and the language system plays the role of a superordinate schema. Likewise, semantic categories are concrete concepts towards the language system; and signs are concrete concepts towards semantic categories. It shows that the level of those basic elements is increased from signs (bottom) to the language system (top), and signs become the most inferior and concrete element, being regarded as a subordinate instance. Considering that the semantic category is in the middle position of this linear relationship, it connects both the system and signs. Thus, it can be regarded as both the schema and the instance, which reflects the relativity of the levels in the language system. Therefore, both the relationship between the language system and semantic categories, and the relationship between semantic categories and signs follow the rule of schema-instance. In this sense, no attempt is made and welcomed to change and reverse their orders.

By comparing the general definition of hyponymy with Saussure’s system-based theory, this paper argues that the relationship between hypernym and hyponym has some similarities with the connections among the language system, semantic categories and signs. Based on this observation, this paper aims to re-explain hyponymy by taking Saussure’s system-based theory as the analyzing perspective.

4. Re-explain hyponymy within Saussure’s system-based theory

Based on Saussure’s system-based theory, this section re-explains hyponymy from both the longitudinal dimension and the crosswise dimension separately, where many concrete examples and diagrams, together with correlated concepts, are adopted and intertwined logically within the analysis.

In the longitudinal analysis, this paper illustrates the hierarchical, transitive, irreversible and relative characters of hyponymy, while the difference and opposition in the same layer are interpreted in the horizontal study.

4.1. Longitudinal research on hyponymy

The longitudinal research on hyponymy is based on Saussure’s system-based theory, and the similarities between its schema-instance relationship and hyponymy. After analyzing the relationship among those basic elements of Saussure’s system-based theory under the framework of the schema-instance, it is easy to find that this framework can also be used to analyze hyponymy, because the semantic relations of hyponymy are mainly represented by semantic categories at the superordinate level which could further determine different semantic relations among linguistic signs.

To begin with, in the connection between the language system and semantic categories, which can be described as the schema-instance relationship, the system is the more schematic notion, while the semantic categories are the instances of the system. The system being in the superordinate position plays the role of hypernym, and the subordinate semantic categories take the responsibilities of the hyponym. Taking the numeral system as an example, the superordinate system or the hypernym [NUMERAL] is schematic to much more delicate subordinate categories, such as [CARDINAL] and [ORDINAL]. In turn, the hyponym or subordinate semantic categories, such as [CARDINAL] and [ORDINAL], instantiate their higher-level system [NUMERAL]. Likewise, the superordinate system [MODAL] is schematic to its subordinate categories or the hyponym [DEONTIC MODAL] and [EPITERMIC MODAL], while the subordinate semantic categories or the hyponym, such as [DEONTIC MODAL] and [EPITERMIC MODAL], instantiate their superordinate system [MODAL].

Moreover, the connection between semantic categories and signs can also be described as the schema-instance relationship, in which the superordinate schema and hypernym are changed into the semantic categories while the subordinate instance and hyponym are changed into signs. For example, the superordinate category (hypernym) [DEICTIC] is schematic to its subordinate categories (hyponym), such as [SPECIFIC; DETERMINATIVE; DEMONSTRATIVE] and [SPECIFIC; DETERMINATIVE; POSSESSIVE]. The first set of categories is schematic to some concrete instances or signs, such as “this”, “that”, “these”, and “those”, and the second set is schematic to some instances or concrete signs such as “your”, “his”, “her”, and “its”. These signs or words instantiate their superordinate semantic category [DEICTIC] of the system. In a similar vein, as we mentioned above, the numeral system has two semantic categories [CARDINAL] and [ORDINAL]. The former is schematic to some concrete signs, such as “1”, “2”, “3”, … “n”; and the latter is schematic to some concrete signs, including “first”, “second” … “nth” [11].

In a word, Saussure’s holistic language system followed the order of system, semantic category and sign (system semantic category sign), as is shown in Figure 1. In this linear relationship, each part of the language system belongs to a certain layer and is independent of one another. To be specific, in hyponymy, the semantic meanings of words follow the order from hypernym to hyponym (hypernym hyponym). As the most abstract concept of this holistic relationship, system and hypernym could determine and even confine the concrete instances of their categories and signs or hyponym, and construct the framework of this whole language system. For linguistic signs, they must instantiate the same semantic category to ensure that they belong to one system.

This holistic relationship can be shown in a tree diagram. Unlike the family tree, which is constructed on the basis of lineage, a tree diagram is used to emphasize the language system’s hierarchical and orderly structure as well as its transitivity.

4.2. Horizontal research on hyponymy

Beyond the longitudinal research, hyponymy can also be explained with the assistance of horizontal research. It requires the comparison among the elements in the same layer. That is, compare categories with other categories or compare signs with other signs.

Saussure [12] held the view that the language system is made up of negative oppositions, as a network of wholly negative values, which exist only in mutual contrast. Therefore, the horizontal relationships among the elements at the same level are full of oppositions. For instance, in the system of [ANIMAL], its semantic categories or hyponyms include [BIRD], [MAMMAL], [AMPHIBIAN] and so on so forth, each of which has its own hyponym or signs. For example, “pigeon”, “crow”, “eagle” and “seagull” are all hyponyms of [BIRD]. In the second layer, neither the pronunciation nor the image of the hyponym or those semantic categories are similar to one another. The third layer faces the same situation: although “pigeon”, “crow”, “eagle” and “seagull” belong to the same level, the pronunciation and images of those signs are totally different and each element is independent of one another. In other cases, the elements in the same layer can be opposite to one another, such as [VOICED] and [VOICELESS] under the system of [VOICE]. Obviously, the categories [VOICED] and [VOICELESS] have different pronunciations, and their concrete signs, such as “cat” and “hat”, have different images.

Based on the system-category-sign relationship, a group of linguistic signs that share the same superordinate category are opposed to one another because they are negatively contrasted with one another in relation to their common categories.

5. Conclusion

By using Saussure’s system-based theory, this paper re-explains hyponymy in two dimensions: longitudinal dimension and crosswise dimension.

In the longitudinal research, this paper finds that hyponymy can be equivalent to the system-sign relationship, which is hierarchical, transitive, irreversible and relative. A sign, a semantic category, or a hyponym cannot be isolated from the system or the hypernym to which it belongs. In the horizontal research, this paper figures out that in the same layer, the relationship among those elements shows the feature of difference and opposition.

All of the findings indicate that language is a holistic system. As a semantic relation, hyponymy also follows the rules and structures of Saussure’s language system, under the guidance of which people can analyze hyponymy from a new perspective and understand hyponymy better.

References

[1]. Cruse, D. A. (2000). Meaning in language: An introduction to semantics and pragmatics. Brown, K., Clark, E. V., Miller, J., Milroy, L., Pullum, G. K., & Roach, P. (Eds.). Oxford, Oxford University Press.

[2]. Fromkin, V., Rodman, R., & Hyams, N. (2007). An introduction to language, tenth edition. Boston, Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

[3]. Huang, Y. (2007). Pragmatics. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

[4]. Holdcroft, D. (1991). Saussure: Signs, systems and arbitrariness. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

[5]. Saussure, F. (1993). Saussure’s third course of lectures on general linguistics (1910-1911). Oxford, Pergamon Press.

[6]. Zhang, Y. F., & Zhang, S. J. (2009). Comparison and interpretation of several key notions of Saussure’s philosophy of language. Journal of Northeast Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences), 2009(5), 162-164.

[7]. Saussure, F. (1959). Course in general linguistics. London, Peter Owen Limited.

[8]. Zhang, S. J. (2004). A study in arbitrariness of linguistic signs: Exploring Saussure’s philosophy of linguistics. Shanghai, Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.

[9]. Zhang, S. J., & Zhang, Y. F. (2015). Scalar implicature: A Saussurean system-based approach. Language Sciences, 2015(51), 43-53.

[10]. Evans, V. & Green, M. (2006). Cognitive linguistics: An introduction. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press.

[11]. Gu, X. B., & Zhang, Y. F. (2013). Saussure’s thought of language as a system: A schema-instance-based approach. Shandong Foreign Language Teaching Journal, 2013(6), 44-48.

[12]. Saussure, F. (2006). Writings in general linguistics. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Cite this article

Yuan,Z. (2025). An Explanation of Hyponymy—From the Perspective of Saussure’s System-based Theory. Communications in Humanities Research,72,14-18.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICADSS 2025 Symposium: Art, Identity, and Society: Interdisciplinary Dialogues

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Cruse, D. A. (2000). Meaning in language: An introduction to semantics and pragmatics. Brown, K., Clark, E. V., Miller, J., Milroy, L., Pullum, G. K., & Roach, P. (Eds.). Oxford, Oxford University Press.

[2]. Fromkin, V., Rodman, R., & Hyams, N. (2007). An introduction to language, tenth edition. Boston, Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

[3]. Huang, Y. (2007). Pragmatics. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

[4]. Holdcroft, D. (1991). Saussure: Signs, systems and arbitrariness. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

[5]. Saussure, F. (1993). Saussure’s third course of lectures on general linguistics (1910-1911). Oxford, Pergamon Press.

[6]. Zhang, Y. F., & Zhang, S. J. (2009). Comparison and interpretation of several key notions of Saussure’s philosophy of language. Journal of Northeast Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences), 2009(5), 162-164.

[7]. Saussure, F. (1959). Course in general linguistics. London, Peter Owen Limited.

[8]. Zhang, S. J. (2004). A study in arbitrariness of linguistic signs: Exploring Saussure’s philosophy of linguistics. Shanghai, Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.

[9]. Zhang, S. J., & Zhang, Y. F. (2015). Scalar implicature: A Saussurean system-based approach. Language Sciences, 2015(51), 43-53.

[10]. Evans, V. & Green, M. (2006). Cognitive linguistics: An introduction. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press.

[11]. Gu, X. B., & Zhang, Y. F. (2013). Saussure’s thought of language as a system: A schema-instance-based approach. Shandong Foreign Language Teaching Journal, 2013(6), 44-48.

[12]. Saussure, F. (2006). Writings in general linguistics. Oxford, Oxford University Press.