1. Introduction

Discourse coherence is a fundamental property of language that enables listeners and readers to interpret sequences of utterances as unified, meaningful wholes. In linguistic theory, coherence is not merely a textual feature but also a cognitive effect constructed by inferential processes and discourse expectations. Understanding how coherence functions is essential for explaining the process of meaning construction and advancing theories of language comprehension. While much research in this field employs spoken texts or expository discourse to examine the logic of coherence, literary works pose unique challenges. Their frequent disruption of chronological narrative order and the deliberate omission or distortion of causal links often complicate the process by which readers establish coherence. These complexities lead to the need for a semantic framework to explain the non-linear, counter-intuitive and seemingly incoherent discourse in literature.

William Faulkner’s A Rose for Emily is a frequently analyzed work of non-linear narrative. The story mixes events from different time periods without explicit time markers, forcing readers to mentally establish the real timeline on their own. Many scholars have looked into the novel’s temporal disorder, collective narrators and thematic expression [1-4]. Such analyses provide rich literary insights, but they are less effective in revealing the underlying discourse structure that guides reader comprehension. There is a lack of systematic investigations from a linguistic perspective that focus on the story’s intentionally incoherent narrative and the effect of such an arrangement within the novel.

This study aims to fill this gap by applying the segmented Discourse Representation Theory (SDRT) to A Rose for Emily as a case study. SDRT provides a systematic explanation for discourse coherence through defined rhetorical relations and constraints on discourse connection [5]. By analyzing the story’s narrative disruption and its function through SDRT, this paper examines linguistic coherence in complex literary texts and contributes to the broader development of coherence theory by extending its application beyond traditional expository and dialogic discourse.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews previous studies on A Rose for Emily and existing literature on discourse coherence and SDRT. Section 3 describes the research methodology and explains the reasons for choosing the text. Section 4 presents the case analysis of A Rose for Emily, applying SDRT principles to its narrative structure. Section 5 concludes with a discussion of the paper’s findings and their implications for future research.

2. Literature review

2.1. Narrative structure of A Rose for Emily

William Faulkner’s A Rose for Emily has long been studied for its narrative structure, which is characterized by a non-linear chronology and deliberate manipulation of time. Early studies, such as Perry’s Theory of Literary Dynamics, argue that the fragmented narrative in the story affects readers’ acquisition of information and their understanding of the events [6]. By delaying and withholding crucial information, the story intensifies its sense of mystery and enhances the themes of isolation and decay, while also directing the emotional and cognitive responses of readers. Similarly, Ahmadian and Jorfi apply Gérard Genette’s theory of narrative time to the story and examine Faulkner’s use of anachrony, including analepsis, pauses, and ellipses [1]. Their analysis underlines the effect of the time dislocations to create suspense and deepen the themes of Southern decline.

Other scholars interpret the non-linear narrative structure as a deliberate strategy adopted by the narrator to serve specific purposes. Skinner claims that the disrupted chronology is not a sign of chaos, but rather an artistic construction based on associative logic (e.g., memory jumps) by Miss Emily herself, whom he considers to be the actual narrator [7]. Through selective memory and certain narrative techniques, Emily succeeded in reframing morbid events as a Southern legend, which reveals the capacity of narrative discourse to whitewash the reality. On the contrary, Melczarek investigates the complexity of narrative motivation in the novel and proposes that the real narrators are the townspeople [8]. He suggests disrupted narrative structure is an intentional strategy of the townspeople to mask their potential involvement in Emily’s crime, which unveils a collective moral hypocrisy within Southern society.

Meanwhile, some scholars analyze the narrative structure to offer new interpretations of the story’s themes. Harris, for example, puts forward the concept of “death time” embedded in the story’s fragmented chronology—a temporal state suspended between life and death, past and present [9]. According to Harris, this disrupted and reorganized sense of time symbolizes the broader tension between Southern tradition and emerging modernity and reveals the Southern community’s resistance to change.

These studies shed light on the complicated narrative techniques employed by Faulkner, with a focus predominantly on literary and thematic analysis. Little of the existing research has incorporated linguistic approaches such as discourse analysis.

2.2. Discourse coherence

Coherence is a key concept in linguistics; it refers to the logical and meaningful connections that allow a series of elements, whether in a sentence or across sentences, to be perceived as a unified whole. Scholars have approached the notion of coherence from various perspectives. Halliday and Hasan distinguish coherence from cohesion, emphasizing that coherence depends not merely on grammatical links but also on the interpretation of texts within the context [10]. Similarly, van Dijk and Kintsch describe coherence as the result of building a mental representation or situation model of the text [11]. While early research considers coherence as a textual feature, more recent studies, such as that of Sanders et al., take a more functional perspective and classify coherence relations into types, such as causal, additive, and temporal, to explain how people construct meaning over segments of discourse [12]. Discourse coherence, therefore, refers to how meaning is constructed across parts of discourse, guided by both linguistic devices and people’s cognitive abilities to create a unified interpretation of the text [13,14].

These foundational theories have led to the development of a range of theoretical frameworks that further explain the establishment and maintenance of coherence in discourse. Rhetorical Structure Theory (RST), proposed by Mann and Thompson, organizes texts into hierarchies of nucleus-satellite relations, explaining how segments of discourse contribute to the writer’s communicative goal [15]. A later framework, the segmented Discourse Representation Theory (SDRT), provides a more dynamic and inferential model, providing an explanation for non-sequential structures and putting forward pragmatically driven discourse relations such as Narration, Elaboration, and Explanation [5].

Recent studies have further expanded the empirical basis of coherence research. Psycholinguistic research examines readers’ mental tracking of coherence through causal inference, referential continuity, and event structure [16,17]. Corpus-based studies validate these models by identifying the manifestation of coherence relations in real texts, confirming the applicability of the theories in authentic discourse [18,19].

2.3. Segmented Discourse Representation Theory (SDRT)

Segmented Discourse Representation Theory (SDRT), developed by Asher and Lascarides, provides a framework for analyzing discourse coherence by segmenting discourse into distinct units, each of which convey an independent eventuality (an event or state) and is linked to others through various discourse relations [5]. These relations indicate the semantic relationships between units and help establish coherence across the segments. SDRT is especially suitable for studying non-linear discourse because it can manage complex relationships between parts of the text and adapt to how ideas are presented, not just their order. This ability makes it useful for analyzing literary works like A Rose for Emily where narrative coherence must be reconstructed through the careful arrangement of discourse relations.

Some recent studies have successfully applied SDRT to literary texts and demonstrate the theory’s efficacy in literary analysis. Meng analyzes Mollie in Animal Farm by segmenting the character’s actions into discrete discourse units and identifying contrast/elaboration relations between them, which reveals the opposition of Mollie’s individualist behavior to the collective ideology [20]. Hao applies SDRT’s Right Frontier Constraint (RFC) principle to The Raven, examining RFC violations in the poem to expose the narrator’s psychological deterioration [21]. Zhou employs both global and micro-analysis of The Lottery, investigating the rhetorical relations between character behaviors and those between key plot points, thereby exploring the multiple themes of the novel [22]. Based on SDRT, these studies examine complex literary texts through discourse segmentation and coherence relations, offering productive models for analyzing non-linear narratives like A Rose for Emily.

3. Methodology

This paper adopts Segmented Discourse Representation Theory (SDRT) to examine the coherence of the narrative structure in William Faulkner’s A Rose for Emily. The novel’s typical non-linear narrative makes it a suitable case for discourse coherence analysis in literary texts. Investigation of the narrative arrangements in the novel demonstrates SDRT’s ability to reveal authors’ underlying intentions in literary works.

Guided by SDRT, the study first divides the story’s plot into several discrete segments and identifies the coherence relations that connect them. It then looks into the relations in order to reveal the implicit coherence embedded in the disrupted narrative structure and to discuss the literary effects it produces both for the story and for its readers.

4. Case study

4.1. Segmentation of A Rose for Emily

Given that this study focuses on the narrative structure of the story, the plot is segmented into discourse units, with key events in the text identified as segments. Table 1 presents the specific events in segments A-G, along with the actual time when they occur, in the narrative order of the story.

|

Segments |

Events |

Time |

|

A |

Miss Emily’s funeral |

Present time |

|

B |

The tax dispute |

Unclear |

|

C |

The smell complaint |

30 years ago |

|

D |

Emily’s father died |

2 years before C |

|

E |

Emily’s relationship with Homer Barron |

Shortly after D |

|

F |

Emily bought arsenic |

1 year after E |

|

G |

Homer disappeared |

After F |

|

H |

Emily became reclusive |

After G |

|

I |

The secret discovered after Emily’s death |

Present time |

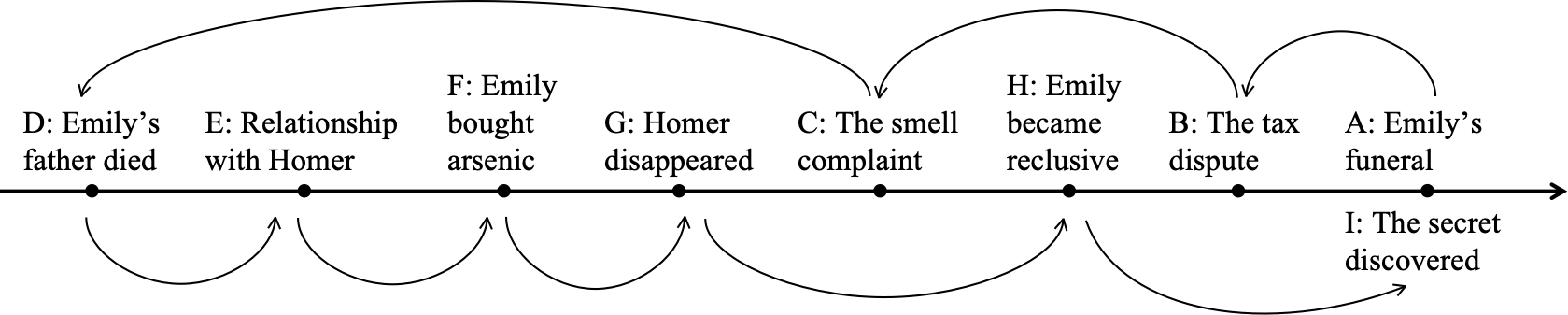

The table illustrates that Faulkner tells the story without following the chronological order, disrupting the natural flow of time. Figure 1 visually represents this non-linear narrative structure. On the axis, the segments are arranged in their chronological sequence, while the arrows show the order in which the events unfold within the story’s narrative.

The figure further demonstrates the disrupted narrative structure in the story. The author begins with Emily’s funeral in the present, then moves backward in time through three flashbacks: the tax dispute, the smell complaint and the death of Emily’s father. After these flashbacks, the story reaches the earliest event, and the narrative returns to the chronological order, presenting the story between Emily and Homer Barron while skipping the events that have previously been described.

On the surface, Faulkner employs various narrative techniques, such as flashback and temporal jumps, disrupting the chronological order and giving the narrative a fractured and seemingly incoherent quality. However, when analyzed through the framework of SDRT and its coherence relations, this study reveals the underlying coherence within the narrative structure and uncovers the author’s intention behind these narrative arrangements.

4.2. Identification of coherence relations

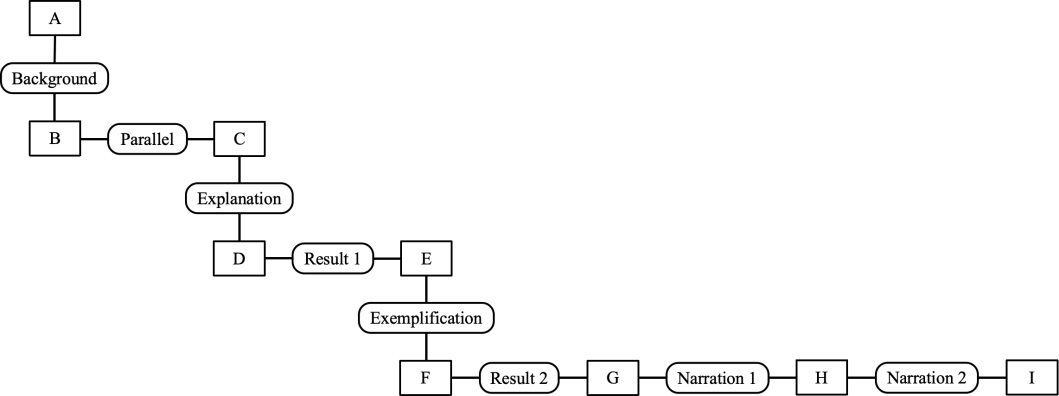

Figure 2 shows the coherent relations between segments A-I. Below is a detailed explanation for each relation.

Background: The story begins with Miss Emily’s funeral, underlining the townspeople’s respect for her. It then flashes back to several decades earlier, when the former mayor remitted Emily’s tax, after which the plot naturally transits to the tax dispute between Emily and the next generation of government officials. The coherence relation between segments A and B is background, as segment B provides an explanation for Emily’s privileged status and thus sets the background for her position in the town and the respect she received in segment A.

Parallel: The coherence relation between segments B and C is Parallel. As the author writes in the novel, “So she vanquished them, horse and foot, just as she had vanquished their fathers thirty years before about the smell.” [23] The two events are connected by their similarity, as segment C is a natural extension of segment B. After presenting the stubborn and solitary personality of Emily in the tax incident, the story proceeds to further illustrate her peculiar character through the complaint about the smell. Segment C thus serves as a complementary extension of segment B, reinforcing the portrayal of Emily. In addition, segment C also complements segment B in terms of showing the townspeople’s respect and fear of Miss Emily, which strengthens her role as the symbol of the South’s glorious past.

Explanation: Unlike the clear connection between segments B and C, the relationship between segments C and D is less apparent. The story transitions from the townspeople’s apology for sprinkling lime around Emily’s house to their recollection of Emily’s father. In fact, however, there is an Explanation relation between the two segments. In segment D, the story describes how Emily was dominated by her father and how she stubbornly refused to acknowledge his death. These descriptions help to explain Emily’s strange and solitary personality established in the earlier segments.

Result 1: In the summer after her father died, Emily met Homer Barron and began a relationship with him. The coherence relation here can be understood as Narration, as the story returns to the chronological sequence following the events in segment D. Nevertheless, there is an underlying Result relation between segments D and E. As the narrative reveals, when Emily’s father was alive, she was unable to have contact with other young men, as “None of the young men were quite good enough for Miss Emily and such.” [23] It was only after her father’s death that Emily had the chance to meet a man like Homer Barron and begin a relationship. Thus, segment E is in fact the result of segment D.

Exemplification: The author connects segment F to segment E by a simple Exemplification relation. At the end of segment E, the townspeople expressed their disapproval of Emily and Homer’s relationship. They described Emily’s proud gesture in the face of gossip and used her purchase of arsenic as an example. This understated transition serves to lower the readers’ guard while the author subtly leads the readers toward the revelation of Emily’s murder of Homer. This technique helps to create suspense and contributes to the shocking impact at the end of the story.

Result 2: Similar to the previous relation, the transition from segment F to segment G is smooth and unremarkable. The author casually announces Homer’s disappearance through the plain narration by the townspeople: “So we were not surprised when Homer Barron--the streets had been finished some time since--was gone.” [23] Such narration obscures the underlying Result relation between the segments: Homer was killed by arsenic and consequently disappeared. This hidden coherence relation remains unrevealed until the story’s conclusion, which also enhances the effects of suspense and shock.

Narration 1 and 2: Segments G and H, as well as H and I, are connected by Narration relations. The events unfold in a clear chronological order.

In summary, while the narrative structure in A Rose for Emily may initially appear with an incoherent quality of disruption and fracture, the coherence analysis reveals that the connections between the story’s events conform to people’s cognitive logic and are, in fact, coherent. Yet this finding raises another critical question: why does the author choose to design such a complicated but internally coherent narrative structure instead of following the chronological order, which is undoubtedly coherent? The answer to this question lies in the literary effects the narrative structure produces.

4.3. Literary effects of the narrative structure

In terms of the readers, the narrative strategy effectively engages their interest. The typical way to introduce a character is to follow their growth and describe the development of their personality. However, Faulkner chooses to present the character of Miss Emily first and then retrospectively explore the factors that shaped her. At the beginning of the novel, Miss Emily strikes readers with a distinctive personality through the townspeople’s respectful attitude toward her and her direct confrontation with government officials. The story then shifts back to the smell complaint, further deepening the portrayal of her as a strange figure. It is only after arousing the reader’s curiosity by these incidents that the author flashes back to the death of Emily’s father and provides an explanation for her peculiar personality. Such arrangements keep readers highly engaged as the story progresses. Also, the immersive reading experience reinforces the readers’ impression of Miss Emily as a solitary and strange character, enhancing her symbolic role and underlining the theme of the South’s stagnation and decline.

Similarly, the narrative structure also enriches the character of the protagonist. The novel begins by presenting Miss Emily as a stubborn and eccentric figure, but as the story develops, it gradually reveals her more vulnerable side, demonstrating her underlying innocence. She is nothing more than a product of the tragedy of her time, shaped and constrained by the oppressive aristocratic Southern society. Her rigid upbringing, along with the harsh expectations of her community, makes her unable to adapt to the changing world around her, leading to her eventual downfall.

By initially moving backward in time, the author maintains a sense of mystery for the readers, with each new segment an unknown aspect of Emily’s life. The narrative then resumes the chronological order, but with suspense about Homer and a revelation until the story’s conclusion. This approach allows each segment to demonstrate a new facet of Emily’s character, and only in the final conclusion does her character achieve full development. The gradual unfolding and multi-dimensional presentation of her personality not only enhances the reader’s engagement with the story but also adds complexity to her character, making her character more layered.

As for the plot, the narrative structure plays a crucial role in building suspense surrounding Homer-related events. After segments A-D, the readers gain a clear understanding of Emily’s character. At this point, the author abruptly shifts from incoherent flashback to the logical chronological narrative, clearly describing the sequence of events: Emily meeting Homer, buying arsenic, and Homer’s disappearance. This straightforward narrative style drives the readers to search for the incoherence beneath the surface of the coherent connections of events. As they are drawn into the mystery, they begin to question why Homer disappeared, and thus suspense is generated. As discussed earlier, the Result 2 relation here is not revealed until the end of the story, creating an unexpected effect and heightening the dramatic tension. The tension is further intensified by the way the story gradually unveils key elements, allowing the final revelation to reach a powerful emotional impact.

In the aspect of thematical expression, the back-and-forth structure mirrors the novel’s central themes of the passage of time and decline. By disrupting the chronological order, Faulkner more directly conveys the oppressive nature of time, as memories of the past, signs of aging, and the looming presence of death alternate throughout the narrative. This structure creates a sense that the past is intertwined with the present and strengthens the air of decay that pervades Emily’s life. The story of Emily is a metaphor for the decline of the South. Through the continual flashbacks to Emily’s past, the story demonstrates the decline of the once-glorious Grierson family, and thus manifests Emily’s—and by extension—the South’s obsession with the past and their inability to escape the inevitable fate.

To summarize, the disrupted narrative structure in A Rose for Emily is not merely a stylistic choice but a deliberate strategy employed by Faulkner to achieve multiple literary effects. By breaking the chronological order, the author strengthens reader engagement, enriches the complexity of Miss Emily’s character, enhances the dramatic tension of the plot, and reinforces the novel’s central themes. In this way, what appears to be incoherence on the surface is, in fact, a carefully designed narrative technique that serves clear and meaningful artistic purposes.

5. Conclusion

This paper investigates the narrative structure and coherence of William Faulkner’s A Rose for Emily using Segmented Discourse Representation Theory (SDRT). Through an in-depth analysis of the story’s non-linear narrative structure, the study identifies the coherence relations between the discrete segments of the plot and explores how these relations, despite the apparent disruption of chronology, contribute to a coherent and meaningful narrative. By analyzing key events and their connections, the study discovers that Faulkner’s unconventional narrative design not only creates suspense and engages the reader’s curiosity but also enriches the protagonist’s character and deepens the themes of time, decay, and the South’s decline.

The main contribution of this paper lies in its application of SDRT to a literary text. The analysis of narrative coherence in A Rose for Emily enhances comprehension of the celebrated novel and offers insights into the broader use of non-linear narrative techniques in literature. Moreover, by providing a concrete case that supports the theoretical framework of discourse coherence in literary contexts, the study strengthens the theory with evidence from literary works. It also demonstrates the effectiveness of SDRT in examining non-linear narrative structure in literature and expands its application beyond traditional texts, encouraging its use in future studies of literary texts and promoting the intersection of linguistics and literary theory.

Apart from the contributions, this study also has some limitations. First, the analysis is based on a single literary text, and the findings are limited by the scope of this case study. Therefore, further research could explore the application of SDRT to a wider range of works or more genres. Second, the study focuses mainly on the structural and thematic aspects, leaving out a more detailed examination of language use and other elements. Future research could consider incorporating these aspects to provide a more comprehensive analysis of coherence in literary texts. Overall, this paper demonstrates the potential of SDRT in analyzing literary texts and expands the scope of discourse coherence theory. Future studies may further explore the application of SDRT to larger corpora and various genres to validate and enrich its theoretical framework.

References

[1]. Ahmadian, M., & Jorfi, L. (2015). A narratological study and analysis of: The concept of time in William Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily”. Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 6(3), 215-224.

[2]. Allen, D. W. (1984). HORROR AND PERVERSE DELIGHT: FAULKNER’S “A ROSE FOR EMILY.” Modern Fiction Studies, 30(4), 685–696.

[3]. Dilworth, T. (1999). A romance to kill for: homicidal complicity in Faulkner's" A Rose for Emily". Studies in Short Fiction, 36(3), 251.

[4]. Scherting, J. (1980). Emily Grierson’s Oedipus Complex: Motif, Motive, and Meaning in Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily”. Studies in Short Fiction, 17(4), 397.

[5]. Asher, N., & Lascarides, A. (2003). Logics of Conversation. Cambridge University Press.

[6]. Perry, M. (1979). Literary Dynamics: How the order of a text creates its meanings [With an analysis of Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily”]. Poetics Today, 1(1/2), 35-64+311-361.

[7]. Skinner, J. L. (1985). “A Rose for Emily”: Against Interpretation. The Journal of Narrative Technique, 15(1), 42–51.

[8]. Melczarek, N. (2009). Narrative Motivation in Faulkner’s A ROSE FOR EMILY. The Explicator, 67(4), 237–243.

[9]. Harris. (2007). In search of Dead Time: Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily.” KronoScope, 7(2), 169–183.

[10]. Halliday, M. A. K., & Hasan, R. (2014). Cohesion in english. Routledge.

[11]. van Dijk, T. A., & Kintsch, W. (1983). Strategies of discourse comprehension.

[12]. Sanders, T. J., Spooren, W. P., & Noordman, L. G. (1992). Toward a taxonomy of coherence relations. Discourse processes, 15(1), 1-35.

[13]. Hobbs, J. (1985). On the coherence and structure of discourse. CSLI Report, No. 85-37.

[14]. Kehler, A., & Kehler, A. (2002). Coherence, reference, and the theory of grammar (Vol. 380). Stanford, CA: CSLI publications.

[15]. Mann, W. C., & Thompson, S. A. (1988). Rhetorical structure theory: Toward a functional theory of text organization. Text-interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of Discourse, 8(3), 243-281.

[16]. Kintsch, W. (1998). Comprehension: A Paradigm for Cognition. Cambridge University Press.

[17]. Zwaan, R. A., & Radvansky, G. A. (1998). Situation models in language comprehension and memory. Psychological Bulletin, 123(2), 162–185.

[18]. Webber, B., Egg, M., & Kordoni, V. (2012). Discourse structure and language technology. Natural Language Engineering, 18(4), 437-490.

[19]. Wolf, F., & Gibson, E. (2005). Representing discourse coherence: A corpus-based study. Computational linguistics, 31(2), 249-287.

[20]. Meng, A. (2024). The Coherence Relations of “Mollie” in Animal Farm under segmented Discourse Representation Theory (SDRT). Communications in Humanities Research, 63, 188-196.

[21]. Hao, Y. (2024). Testing Right Frontier Constraint on Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media, 36, 62-70.

[22]. Zhou, Y. (2024). A Coherent Analysis of The Lottery by Shirley Jackson Using segmented Discourse Representation Theory. Communications in Humanities Research, 39, 156-165.

[23]. Faulkner, W. (1930). CommonLit | A Rose for Emily. CommonLit. https: //www.commonlit.org/en/texts/a-rose-for-emily

Cite this article

Zhao,Y. (2025). Understanding Discourse Coherence Through SDRT: A Case Study of A Rose for Emily. Communications in Humanities Research,74,52-60.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICADSS 2025 Symposium: Art, Identity, and Society: Interdisciplinary Dialogues

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Ahmadian, M., & Jorfi, L. (2015). A narratological study and analysis of: The concept of time in William Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily”. Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 6(3), 215-224.

[2]. Allen, D. W. (1984). HORROR AND PERVERSE DELIGHT: FAULKNER’S “A ROSE FOR EMILY.” Modern Fiction Studies, 30(4), 685–696.

[3]. Dilworth, T. (1999). A romance to kill for: homicidal complicity in Faulkner's" A Rose for Emily". Studies in Short Fiction, 36(3), 251.

[4]. Scherting, J. (1980). Emily Grierson’s Oedipus Complex: Motif, Motive, and Meaning in Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily”. Studies in Short Fiction, 17(4), 397.

[5]. Asher, N., & Lascarides, A. (2003). Logics of Conversation. Cambridge University Press.

[6]. Perry, M. (1979). Literary Dynamics: How the order of a text creates its meanings [With an analysis of Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily”]. Poetics Today, 1(1/2), 35-64+311-361.

[7]. Skinner, J. L. (1985). “A Rose for Emily”: Against Interpretation. The Journal of Narrative Technique, 15(1), 42–51.

[8]. Melczarek, N. (2009). Narrative Motivation in Faulkner’s A ROSE FOR EMILY. The Explicator, 67(4), 237–243.

[9]. Harris. (2007). In search of Dead Time: Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily.” KronoScope, 7(2), 169–183.

[10]. Halliday, M. A. K., & Hasan, R. (2014). Cohesion in english. Routledge.

[11]. van Dijk, T. A., & Kintsch, W. (1983). Strategies of discourse comprehension.

[12]. Sanders, T. J., Spooren, W. P., & Noordman, L. G. (1992). Toward a taxonomy of coherence relations. Discourse processes, 15(1), 1-35.

[13]. Hobbs, J. (1985). On the coherence and structure of discourse. CSLI Report, No. 85-37.

[14]. Kehler, A., & Kehler, A. (2002). Coherence, reference, and the theory of grammar (Vol. 380). Stanford, CA: CSLI publications.

[15]. Mann, W. C., & Thompson, S. A. (1988). Rhetorical structure theory: Toward a functional theory of text organization. Text-interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of Discourse, 8(3), 243-281.

[16]. Kintsch, W. (1998). Comprehension: A Paradigm for Cognition. Cambridge University Press.

[17]. Zwaan, R. A., & Radvansky, G. A. (1998). Situation models in language comprehension and memory. Psychological Bulletin, 123(2), 162–185.

[18]. Webber, B., Egg, M., & Kordoni, V. (2012). Discourse structure and language technology. Natural Language Engineering, 18(4), 437-490.

[19]. Wolf, F., & Gibson, E. (2005). Representing discourse coherence: A corpus-based study. Computational linguistics, 31(2), 249-287.

[20]. Meng, A. (2024). The Coherence Relations of “Mollie” in Animal Farm under segmented Discourse Representation Theory (SDRT). Communications in Humanities Research, 63, 188-196.

[21]. Hao, Y. (2024). Testing Right Frontier Constraint on Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media, 36, 62-70.

[22]. Zhou, Y. (2024). A Coherent Analysis of The Lottery by Shirley Jackson Using segmented Discourse Representation Theory. Communications in Humanities Research, 39, 156-165.

[23]. Faulkner, W. (1930). CommonLit | A Rose for Emily. CommonLit. https: //www.commonlit.org/en/texts/a-rose-for-emily