1.Introduction

In the 20th century, modern linguistics was introduced to China, and many books and works on phonetics and dialect studies were translated into Chinese thus, the research results of Chinese phonetic descriptions contributed to the development of phonetic studies. Nowadays, English has become an international language, and with the flourishing of socialism with Chinese characteristics, the importance of learning English well has become an urgent need for Chinese students. There is no doubt that the correct and clear English pronunciation plays an important role in successful cross-cultural communication. Each language has its own unique rules, and each syllable has its own specific rules, both in terms of distribution and composition. Normal communication, including intelligibility, might benefit from having a clear pronunciation of the language. [1]. Influenced by their native language, Chinese students often transfer features of Chinese phonology to English phonology acquisition. In the English phonological system, the imitation of consonants, stress, and intonation is more complex, and the subtleties of pronunciation differences are not easily perceived by the naked eye and ear. This study will reveal the problems of Chinese students in consonants, stress, and intonation through a comparative phonological analysis of English and Chinese phonetics, and suggest some practical methods for teaching English pronunciation specific to these problems.

2.Basic Concepts and Research Design

2.1.Consonants

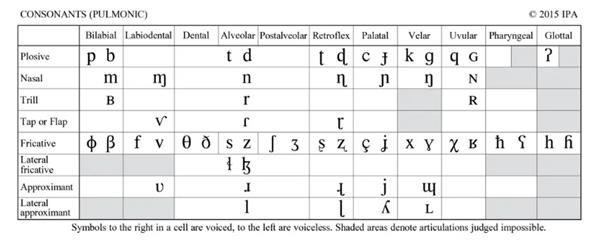

As shown in Figure 1, the consonant of English is one of the classifications of sounds. It is mainly determined by the two types of pronunciation, obstruent and sonorant. In the former case, there is closure of the articulatory organ and therefore an obstruction is produced, which is called obstruent; in the latter case, there is no obstruction and all vowels are loud.

Figure 1: The international phonetic alphabet for consonants [2].

The syllable structure of consonants is relatively complex and the consonants are pronounced with the back lung breath and have the same constrictions. There are many different types of consonants depending on how they are pronounced, For example, stop (implosive), affricative, and fricative in the obstruent branch, but what they all have in common is that they obstruct the vocal tract's ability to move air.

2.2.Stress-timed (Stress) and Syllable-timed (Intonation)

Languages can be classified according to whether they are stress-timed (stress) or syllable-time (intonation). In the past, it was thought that in English languages with stress timing (stress), the distance between stresses was equal, although there were variations in the amount of syllables between each stress. As a result, if there are several stresses between two accents, certain syllables must be uttered rapidly, and if there are few, some syllables will be delivered slowly. The syllable structure of syllable-timed (intonation) in syllable length varies is shorter than that of stress-timed (stress), and vowels may be shortened or omitted.

2.3.Research Design

Each fricative is represented by a segment that is either non-periodic (voiceless consonant) or periodic (superimposed consonant). These are good examples to test the pronunciation of consonants, stress, and intonation. The sounds listed were specifically set up to test the subjects of this paper, high school students in Hefei. These sounds are /f/, /v/, /ð/, /s/, /z/, as in words pronounce like /fie/, /vie/, /thy/, /sigh/, /zion/.

3.Related Reasons about Second Language Acquisition and Phonology

3.1.First Language Transfer and Second Language Acquisition

Behaviorist views of language learning and language teaching dominated the two decades following World War II. These views draw on Stevick, and Guior et.al. [3, 4, 5]. According to behaviorist theory, the biggest obstacle to learning is the interference of a priori knowledge. Active inhibition occurs when old habits prevent you from learning new habits. When people grow up, the habits of their own language are so strong that language habits are difficult to break and reshape. It is as if each person has a fixed number of rooms in his or her mind to store different sounds. When learners hear the pronunciation of their native language, they put each pronunciation into the correct room, and when they speak, the learner goes and opens the door to the room and takes those pronunciations out. Over time, the learner puts everything they hear, whether it is their own language or not, into these rooms. This means that everything the learner says comes out of these rooms. But each language has a different number of rooms, and the rooms are arranged in different ways. For example, the native English speaker’s room contains these three sounds at the beginning of the words /fin/ /thin/ /sin/, written in consonant like this:

Table 1: Examples of three sounds in native English speaker’s room.

/f/ /θ/ /s/

In the Chinese language we do not have a special room for the consonant /θ/. Therefore, we can show the Chinese language room in the following form:

Table 2: Examples of English learners with Chinese as their first language that contain these two sounds in their room.

/f/ /s/

The habits of English learners with Chinese as their first language will force them to put what they would have heard /θ/ into /f/ room or /s/ room, and then their pronunciation is either like /fin/ or /sin/, naturally the pronunciation will be incorrect.

3.2.First Language Learners Face the Problems of Second Language Phonology

Second-language phonological acquisition is an important topic in the study of phonology. As an interdisciplinary subject, it involves not only phonology and phonetics, but also the combination of various linguistic knowledge such as psycholinguistics, cognitive linguistics, and pedagogy.

3.2.1.Age

There is clear evidence of a relationship between the age of language acquisition and the foreign accent. [6]. In general, learners of a second foreign language who are older than six years of age rarely have problems with their accent. If the learner starts learning a second language between the ages of 7 and 11, the learner usually has a slight accent. If the student learns after the age of 12 years, the learners will almost always have accent problems [7, 8]. A more plausible argument is that students have learned the phonological system of their first language, which increasingly influences their perceived linguistics for second and subsequent languages. Age affects this understanding as the first language system becomes increasingly integrated and stable The psychological explanation is that assertiveness is part of what is characteristic of people, and as they get older, people become more protective of their personalities and less willing to change their accent.

3.2.2.Fear of Difficulty

Students feel bad when they translate well. People are often sensitive to their English accent because it allows others to identify their identity, status, and background. In addition, if learners pronounce English well, others may assume it is because they like foreign cultures and want to be like foreigners. However, such an idea is often not recognized by learners and creates a sense of fear over time. This may be the sounds or other features of the foreign language (intonation or stress, sounding like /ð/, /f/) are strange to learners because they have never been exposed to them before, so they may not want to reproduce them correctly, even if they can. Learners can become anxious about making these sounds and thus fearful. If the teacher tells the students that they did not say something correctly, they can become very nervous and helpless, causing them to fail to pronounce the word correctly next. Therefore, teachers need to find ways to help learners understand their pronunciation instead of making them worry about their mispronunciation because they are shy and fearful.

3.2.3.The Experience and Attitudes of the Learner

Each student brings different life experiences and perspectives to the classroom which can affect the learning of new sound system. Purcell and Suter examined nearly two dozen influential factors that may affect English pronunciation of second language learners, such as the number of years the learner has lived in an English-speaking country, and the number of English speaking training sessions, the number of languages the learner has mastered (bilingual learners) [9]. They also included attitudinal factors such as the learner's type of motivation (economic, social prestige, general), the learner's desire for accurate pronunciation, the learner's imitation skills, and whether the learner was extroverted or introverted. Purcell and Suter found that the factors most associated with pronunciation success was the number of years spent in an English-speaking country, versus the number of months the student spent with native English speaker, the learner's first language, and the number of months the learner had lived with a native English speaker, the learner's desire for accurate pronunciation, and the learner's imitation skills. In general, a passionate attitude and some English learning skills are necessary for learners to learn a second foreign language well.

4.Procedures and Techniques in Teaching Methods

4.1.Articulation of Individual Sounds

It is important for teachers to practice continuously in response to learners' voices in individual questions, and informed teachers can significantly improve learners' pronunciation through such practice [10]. This type of instruction needs to be based on the teacher's observation, analysis, and selection, possibly by first allowing the learners to hear the differences between the sounds they make on their own and the standard sounds, and to identify the specific sounds before guiding them to their own pronunciation. When teaching the individual sounds or correcting pronunciation, teachers can follow several steps:

(a). Whether or not the learner's pronunciation has the same sound as they would like to make in their first language, Chinese? (Examine the influence of the first language on the second language learning and identify what sound the learner put in place of the wanted sound)

(b). Does the mistakes occur at the beginning, middle, or end of each individual sound? (By observing , teachers can figure out whether a consonant, the vowel or another specific sound system has made mistakes)

(c). What is the difference between the sounds teachers want students to make and the sounds students actually make? (Specific problems use specific methods, teachers can clearly point out the mistakes to the students, making it more convenient to correct the pronunciation)

4.2.Teaching the Sound

The first step is to have the students repeat the teacher`s voice. Failing that, the teacher should explain the position of the tongue and lips in relation to the sound type to help the learner pronounce the If the student is unable to make the correct sound even after trying to imitate the teacher, the teacher can usually force their mouth into the correct position. For example, if learner says /v/ like /w/, teachers must have to ask learners to push their lips into the correct position so that their learner's teeth and lips are forced to release and make the correct sound /v/. Therefore, teachers should carefully observe and distinguish the types of errors and decide which method to use to correct students' pronunciation.

In a description of certain sounds, this teaching method can help learners distinguish the difference between correct pronunciation and incorrect pronunciation. It is recommended that teachers provide help in "describing the correct pronunciation" before the learner listens, rather than just correcting errors after listening [11], to prevent repetition of misremembering and avoidable accent errors. In some cases, teachers can describe the difference between the two sounds in the students' first language and draw students' attention to important parts of the sound that are more abstract and easier for them to understand and feel. For example, before practising listening to distinguish between /d/ and /ð/, the teacher could signalize that /ð/ is longer than /d/, that /ð/ is a continuous sound, and that /d/ is like a small explosion "BOOM". Such use of the learner's first language for description is usually intuitive and interesting.

4.3.Correcting Pronunciation Mistakes

Consultation on mispronunciation is a given, but teachers need to think carefully about the way they choose to correct it. For second language learners, it is very important that the teacher assist with pronunciation and help the learner build confidence.

(a). The teacher repeating the word several times correctly with an accent, intonation, until the student gets it right in imitating of the teacher.

(b). The teacher repeats the word correctly, accompanied by a tap on the table to give the learner the part that made the mistake in a rhythmic manner based on extra stress and length.

(c). The teacher used "not......but......" to put the incorrect pronunciation and the correct pronunciation in one sentence and let the learners distinguish the difference.

5.Conclusion

Pronunciation errors such as consonants, stress, and intonation, can be attributed to inappropriate teaching in China or a lack of understanding of how to pronounce English words. Sometimes, even when learners become aware of errors, learn to recognize them and correct themselves, they may fall back into old habits of mispronunciation. There are many factors that affect the pronunciation of second language learners, such as interference from the first language, the learner's attitude and age.

Certainly, it’s a long way for Chinese learners of English pronunciation to go. As mentioned earlier, Chinese learners have many difficulties pronouncing English consonants, stress and intonation. What we have done in this study is only a general estimate based on the learning and life experiences. There are many other factors that affect Chinese learners' inaccuracy in pronunciation of consonants, stress and intonation, such as regional dialects, the teaching environment, etc. And it do not exclude that there are some other factors that affect Chinese learners' pronunciation in real situations. Due to the lack of time and reference materials, the author cannot fully cover all the influencing factors and offer targeted teaching suggestions. Due to time and capacity constraints, many potential details of this study and its discussion of findings have been overlooked though. Correlations between gender, region, and upbringing of second language learners could be included in further research studies.

References

[1]. Munro, M., Derwing, T., & Morton, S. (2006). THE MUTUAL INTELLIGIBILITY OF L2 SPEECH. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28(1), 111-131. DOI: 10.1017/S0272263106060049

[2]. Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License. (2015). 2015 International Phonetic Association. Online: https://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org/sites/default/files/IPA_Kiel_2015.pdf

[3]. Stevick, E.W. (1978). Toward a practical philosophy of pronunciation: another view. TESOL Quarterly, 12(2): 145-150.

[4]. Guiora, A.Z., Beit-Hallami, B., Brannon, R.C.L., Dull, C.Y. and Scovel, T. (1972a). The effects of experimentally induced changes in ego states on pronunciation ability in a second language: an exploratory study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 13: 421-428.

[5]. Guiora, A.Z., Brannon, R.C.L. and Dull, C.Y. (1972b). Empathy and second language learning. Language Learning, 22(1): 111-130.

[6]. Patowski, M. (1990). Age and accent in a second language: a reply to James Emil Flege. Applied Linguistics, 11: 73-89.

[7]. Tahta, S., Wood, M. and Lowenthal, K. (1981a). Age changes in the ability to replicate foreign pronunciation and intonation. Language and Speech, 24(4): 363-372.

[8]. Tahta, S., Wood, M. and Lowenthal, K. (1981b). Foreign accents: factors relating to transfer of accent from the first language to the second language. Language and Speech, 24(3): 265-272.

[9]. Purcell, E.T. and Suter, R.W. (1980). Predictors of pronunciation accuracy: a re-examination. Language Learning, 30(2): 271-87.

[10]. Pennington, M.C. and Richards, J.C. (1986). Pronunciation revisited. TESOL Quarterly, 20(2): 207-225.

[11]. George, H.V. (1972). Common Errors in Language Learning. Rowley, Mass.: Newbury House.

Cite this article

Li,H. (2023). Analysis of Current Pronunciation Errors about Stress, Intonation and Consonant among Chinese Students. Communications in Humanities Research,5,201-206.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Munro, M., Derwing, T., & Morton, S. (2006). THE MUTUAL INTELLIGIBILITY OF L2 SPEECH. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28(1), 111-131. DOI: 10.1017/S0272263106060049

[2]. Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License. (2015). 2015 International Phonetic Association. Online: https://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org/sites/default/files/IPA_Kiel_2015.pdf

[3]. Stevick, E.W. (1978). Toward a practical philosophy of pronunciation: another view. TESOL Quarterly, 12(2): 145-150.

[4]. Guiora, A.Z., Beit-Hallami, B., Brannon, R.C.L., Dull, C.Y. and Scovel, T. (1972a). The effects of experimentally induced changes in ego states on pronunciation ability in a second language: an exploratory study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 13: 421-428.

[5]. Guiora, A.Z., Brannon, R.C.L. and Dull, C.Y. (1972b). Empathy and second language learning. Language Learning, 22(1): 111-130.

[6]. Patowski, M. (1990). Age and accent in a second language: a reply to James Emil Flege. Applied Linguistics, 11: 73-89.

[7]. Tahta, S., Wood, M. and Lowenthal, K. (1981a). Age changes in the ability to replicate foreign pronunciation and intonation. Language and Speech, 24(4): 363-372.

[8]. Tahta, S., Wood, M. and Lowenthal, K. (1981b). Foreign accents: factors relating to transfer of accent from the first language to the second language. Language and Speech, 24(3): 265-272.

[9]. Purcell, E.T. and Suter, R.W. (1980). Predictors of pronunciation accuracy: a re-examination. Language Learning, 30(2): 271-87.

[10]. Pennington, M.C. and Richards, J.C. (1986). Pronunciation revisited. TESOL Quarterly, 20(2): 207-225.

[11]. George, H.V. (1972). Common Errors in Language Learning. Rowley, Mass.: Newbury House.