1.Introduction

From around 1960s, postmodernism has started to prevail, challenging the "universal truths" modernism promote while endorsing broad skepticism and relativism. As one of the most well-known postmodernists, Cindy Sherman has created famous works like Untitled Film Stills, Centerfolds (1981), Society Portraits (2008), etc., using materials that seem to testify for a "ceased originality" that postmodern works feature and casting doubt upon a definitive sense of self by transforming herself into various identities in photogrpahs to display the diversity of human types and to refute stereotypes. Among all her photographs, there is a central theme that Cindy Sherman strives to comprehend and express——feminism. She incorporates humor to construct female identities, to inquire gender relationships, and to reflect on the social gender structure. Rather than glamourous portrait, Cindy Sherman favors grotesque representations: she presents various body shapes to critize morbid aesthestic pursuits of "perfect" body, her makeup is always poorly blended, and her wigs are slipping off to imply that artificiality exists in all kinds of identity constructions; she confronts her audience by offering a visceral sense of otherness and voyeurism which reveals the dark aespects of humanity.

Though she is normally categorized as a postmodernist, her works show a slight deviation from Fredric Jameson's theory on postmodernists' use of pastiche and the sense of superficiality and emptiness achieved consequently. It is true that Cindy Sherman's works show a mimicry in forms to 20 century movies, commercial photographs, or references to fairy tales. However, the well-designed settings, the otherness expressed in increasingly deforming make-ups, and the voyerusim offered by characters' vulnerability achieved by their poses and expressions together convey a sarcastic or even disgustful connotation rather than a neutral and blank imitation. This leads her works beyond a mere nostalgic pasthiche to a complicated reflection of female roles in the patriarchal society and a positive display of new female identities, which is not empty at all.

2.Interpretations of Fredric Jameson's Theory

To fully examine to what extent Fredric Jameson's theories hold true in Cindy Sherman's photographs, it is critical to interpret Jameson's theories first. Jameson believes that a new category must be invented to describe films like the Star War——or more broadly, other art forms like literature and photographs——which seeks to reawaken a sense of the past by "reinventing the feel and shape of characteristic art objects of an older period[4]." They cannot simply be called historical genres because they do not "reinvent a picture of the past in its lived totality[4]." By this definition, Cindy Sherman's Untitled Film Stills falls into the nostalgia genre since Cindy Sherman evokes movie scenes and mimics styles of actresses in her work by wearing makeups, dressing up in costumes, and selecting props. Her works seem to confirm Jameson's theory on pastiche. Jameson states that "one of the most significant features or practices in postmodernism today is pastiche[4]." Pastiche is different from parody since pastiche refers to the neutral imitation of a peculiar style, while parody normally has a satirical impulse or implements humor. The effect of using pastiche can be illustrated by Jameson's comments on the contrast between Van Gogh's depiction of shoes and Andy Warhol's:

But there are some other significant differences between the high modernist and the postmodernist moment, between the shoes of Van Gogh and the shoes of Andy Warhol. The first and most evident is the emergence of a new kind of flatness or depthlessness, a new kind of superficiality in the most literal sense, perhaps the supreme formal feature of all [postmodernisms] [4].

With a culture of pastiche (extensive mimicries of former styles and loss of artists' own styles), Jameson contends, postmodernists create a new kind of flatness and depthlessness in both their works and the society.

3.Cindy Sherman's Usage of Pastiche

Cindy Sherman's photographs exhibit the usage of pastiche in two ways——both obvious and soft-core imitation. In her Untitled Film Stills, Cindy Sherman evokes a style of film scenes by choosing clothes and compositions of photos. The photographs are normally connotated to fall into the nostalgia genre because of this specific artistic choice. The visual resemblance between Cindy Sherman's photograph and the mid-20 century Hollywood movies seems to confirm Jameson's comment that "we had become incapable of achieving aesthetic representations of our own current experience[4]," which shows the society's inability to deal with time and history. Furthermore, Sherman's works also show a sense of soft-core pastiche, as illustrated by Laura Mulvey, because the photographs appear to have the same format with most of the figures lying on sofas, beds, or floors, giving out private emotions of females such as longing and reverie[7]. However, despite the mimicry in styles, Cindy Sherman does offer unique insights about how the patriarchal society reduces females to dual functions of taking care of families and having sexual appeals——through makeups, background setups, and carefully chosen viewing angles——and does incorporate some of her visions of females in works, which are not incoherent at all.

4.Masterful Design of Setups for Construction of Positive Female Identities

4.1.Case Study—— Untitled Film Still #13

Sherman's masterful design of background setups to indicate insights can be well exemplified by her Untitled Film Still #13. Trying to evoke the image of Brigitte Bardot (a French actress in the 1950s who is famous for portraying sexually emancipated characters) in a 1963 movie Contempt (see figure 2), Cindy Sherman wears a long blonde hair and a headscarf. What makes this photo really stick out from various nostalgic works is that Cindy Sherman situates the Bardot-like character in front of a bookshelf, the character trying to reach for a book. Brigitte Bardot herself has never been depicted in such intellectual context in films. In Contempt, Bardot plays the wife of a playwright who uses her to cement his own ties with an American producer to further his career in film industry. By situating the character in an intellectual background, Cindy Sherman moves from a superficial depiction of females' sexual appeals to suggest that females can also take on initiatives to learn and should receive the same kind of intellectual regards as men do. By ingeniously drawing a contrast between the model in her photograph and the wife Bardot plays in the movie Contempt, Cindy Sherman discloses the fact that female characters depicted in films under male gaze are normally brainless accessories of males.

Figure 1: Untitled Film Still # 13 Figure 2: Brigitte Bardot in the film Contempt

4.2.Case Study—— Untitled Film Still #25

Similarly, Cindy Sherman also evokes a scene of Francois Truffaut's movie Jules et Jim in her Untitled Film Still #25. In the end of the film, Catherine, the female leading role, asked her lover Jim to get into her car and drove the car off a damaged bridge into the river, killing herself and lover Jim while mentally destroying their friend and lover Jules because she could not accept that Jim did not love her anymore. Catherine was portrayed as a crazy and desperate lover, a woman who lived her life on males' love and would do anything including ending her life to prove or reawaken that love. In Untitled Film Still #25, Cindy Sherman also photographs herself in front of a river. However, the rippling of the river, combined with the woman standing on the bridge, seems to suggest that the woman's lover has driven off into the river alone. Contrasting Catherine's rage when finding out that Jim no longer loves her, the figure in this photo seems confused but calm instead of hysterical and desperate. Cindy Sherman seems to dispute the stereotype that females tend to be emotional: they require lots of love, and they become hysterical if they don't. Rather, the figure is walking away into a new life, which shows females' independence and wisdom: logic and calmness are not things that only men can have.

Figure 3: Untitled Film Still #25.

4.3.Case Study—— Untitled Film Still #35

If the above two instances are merely critics' specualtions, this one gives a hard proof. Cindy Sherman herself admits that she alludes to Vittorio De Sica's La ciociara in Untitled Film Still #35[18]. In this photograph, Cindy Sherman wears a dress resembling the dress of Loren (see Figure 5, both dresses feature flowery elements), a woman who experiences immense wartime suffering in the film. What's interesting is that a cable shown in the background of the photograph is the cable connected to Sherman's camera's shutter which is controlled by the artist herself. In the film, however, the cable is used to torture Loren. Cindy Sherman challenges the image of the persecuted females. By presenting females with initiatives and control over themselves, Cindy Sherman objects the persecution and torture on women and encourage females to take controls of their own lives. The three works discussed all show that the power of males in society is reinforced again and agian by "reducing" females to representations of sexual desires and housekeepers through multiple cultural products like movies, magazines, and fashion designs, etc. Besides the two roles of females in society, Cindy Sherman also challenges other female stererotypes: she points out that females are not emotional, brainless, and superficial and that they deserve to be regarded as having equal logic, intelligence, and independence as men.

Figure 4: Untitled Film Still #35. Figure 5: Loren (left) in the film La ciociara.

5.Utilization of Exaggerated Makeups for Criticism

Despite imitating the styles of notable directors but creating positive images for the females through the choices of settings and props, Cindy Sherman intensively utilizes makeups during her metamorphoses to offer indications of her attitudes, which contradicts the skill of blank mimicry that postmodernists always use. She does so primiarily out of two reasons. First, in her Untitled Film Still series, Cindy Sherman wears cosmetics as real masks when trying to imitate film scenes. The emphasis on the masquerade of appearances seems to suggest that identities may lie in looks. The other reason is that she desires to show that wearing makeups is not a way of catering males' aesthetic pursuits and to criticize the morbid aesthetic pursuits (for instance, to be very thin) that males force on females, as is especially shown in the fashion industry. From Cindy Sherman's Untitleds of 1983 (see figure 6), she starts to wear heavier and heavier makeups. Cindy Sherman herself admits that this series is designed to mock at the fashion industry and its flawed aesthetic pursuits:

From the beginning there was something that didn't work with me, like there was friction. I picked out some clothes I wanted to use. I was sent completely different clothes that I found boring to use. I really started to make fun, not of the clothes, but much more of the fashion. I was starting to put scar tissue on my face to become really ugly. This stuff you put on your teeth to make them look rotten. I really liked the idea tht this was going to be for French Vogue, amongst all these gorgeous women in the magazine I would be these sick-looking people[20].

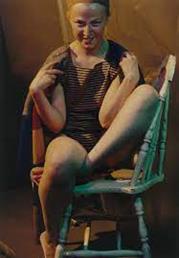

Figure 6: Untitled #123.1983

From 1983, Cindy Sherman starts to wear exaggerated (sometimes even clown-like) makeups, to make awkward poses that emphasize the heaviness of body, and to pick camera angles and lighting that create high-contrast colors. Cindy Sherman in these photographs is not wearing makeups just to look beautiful. Instead, Cindy Sherman puts on makeups as a part of her identities(though the identity is perhaps disguised, as discussed in the former paragraph). The photographs show that the pursuit of a perfect body shape and smooth skin due to the polished photographs fashion magazines publish is a somehow twisted aesthetic pursuit, evoking anxiety, shame, and abasement of females. The fashion industry, a male-dominated industry in the twentieth century, perfectly reflects that under male gaze, females are consumed just like products: they are supposed to look pretty and to please males. This increasing otherness lurking in the photographs created by funny or even grotesque makeup reaches a climax when Cindy Sherman creates her Fairy Tales series (see figure 7 as one example), representing herself as supernatural beings. Differentiated from her former works, the Fairy Tales series seems to show an obvious disclosure of otherness rather than a lurking sense of otherness, directly pointing out Cindy Sherman's disgust towards sexual detritus[19].

Figure 7: Fairy Tales 1985.

6.Gesture and Expression Selections for Sense of Voyeurism

Figure 8: Untitled Film Still #34. Figure 9: Untitled Film Still #2.

What's more, Cindy Sherman also utilizes the poses and expressions of her figures to show voyeurism. In the Untitled Film Stills, the female figures are usually captured as unguarded, sometimes even undressed, sinking into her own world in private environments such as bathrooms or bedrooms(see figure 8 and 9 as examples). Or sometimes, the figure is suddenly startled by a presence watching her. This intrusive gaze offers the viewer a sense of voyeurism. However, the choice that Cindy Sherman uses herself as the model makes things more complicated: she seems to disguise the voyeurism on the offer, making viewers question at the credibility of the illusion. Cindy Sherman-the artist seems to materialize the gaze uncomfortably, in alliance with Cindy Sherman-the model. This voyeurism is uncomfortable to the viewers. The storytelling of the photographs provokes a mixture of curiosity and anxiety of viewers: sexuality pervades.

7.Visual Flatness as Contrary to Superfaciality of Theme

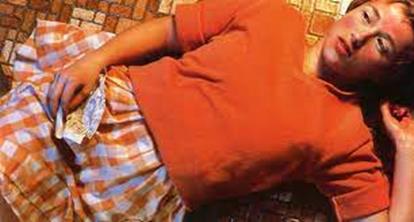

Some may argue that some of Cindy Sherman's photographs, especially her Untitled Film Stills series, appears cheap, trashy, and flat, like some commercial advertisements, which exemplifies that her photographs are depthless. In these photographs, the figure is often merged with the texture and the material of the photograph, making the figure less stereoscopic——instead of a real person telling a real narrative, the model may seem to be "manifested" only based on the need of the photos. For instance, in her 1981 series, Cindy Sherman uses color, light and shades to merge the female figure and her surroundings into a continuum, without hard edges. In Untitled #96, her skin is illuminated with a soft glow achieved by pools of orange light. This hue seems to make her echoing with the orange background and clothes, reinforcing the viewer's feeling that the model seems to be depthless, as flat as the floor she lies on. Above all, the material of the photograph shows a glossy, polished finish, which coincides with the conventions of commercial photography. Although it is true that some of Cindy Sherman's photographs exhibit a flatness in their visual forms as illustrated above, it does not mean that Cindy Sherman's photographs fully confirms Fredric Jameson's theory because when Jameson mentions flatness, he refers to both the flatness and superficiality in visual forms achieved by textures, styles, and color and the emptiness in topics of artworks. Jameson believes that with the use of pastiche and the development of capitalism, postmodern works cultivate a cultural trend of focusing on the surface appearance rather than the depth. Thus, he states that the postmodern culture values the signifier rather than the signified, which means that the linguistic sign loses its value. The absence of depth leads to a culture where appearances and surface meanings are the only things people care. However, Cindy Sherman's photographs clearly contradicts this sole concentration on surface meanings. Cindy Sherman has hidden so many Easter Eggs in her photographs: her purposedly chosen settings, props, makeups, and filming angles give us, audiences, so much to unpack, to interpret, and to comprehend. As analyzed in the former paragraphs, Cindy Sherman sure gives out clues to unpack enigmas in her seemingly simple and flat photographs to see the feminism ideas behind.

Figure 10: Untitled #96.

8.Conclusion

Throughout her life, Cindy Sherman plays with both visual and cultural codes to construct different identities in her artworks, investigating diversity of humans (especially females) and speaking out her attitudes in artworks via humor or sarcasm, two of her most masterful techniques. There is no doubt that Cindy Sherman's works contain a lot of nostalgic elements: Cindy Sherman alludes to famous scenes in the twentieth-century Holleywood B movies in her Untitled Film Stills, mimics styles of fashion posters and commercial photogrpahs in her 1983 Untitleds, and rerepresents fairy tales in her Fairy Tale series. The appearances of historical, cultural, or artistic symbols in her works seem to confirm Fredric Jameson's theory that postmodern artists employ a technique of "blank mimicry" to formal styles and fail to originate new meanings, which shows an inability to cope with present but a strong impulse to look back into the history. With that inability to create new styles and to live at the present, Jameson argues, postmodernists convey an emptiness, depthlessness, and superficiality in their artworks and spread these senses into postmodern society.

However, the mimicry to former film and poster sytles are not a blank mimicry. Instead, they are deliberately chosen styles to best advertise the information. The first reason for this choice is to create sarcasm and thus offer insights. People in that era have been exposed in these forms of cultural products and commercial products for a very long time on mass media and have become numb at sensing the lurking otherness, the uncomfortable voyeurism, or the twisted view of aesthetics presented. By following the conventions of styles while altering background settings, props, makeups, and figure gestures and expressions, Cindy Sherman exaggerates these lurking elements to expose them, to criticize them, and to give them new wishes or meanings. The second reason is that in the mass media landscape in the 1970s, these forms are best for spreading out ideas and earning attention. Only if her works receives attention, the issues investigated in her works can be examined by the public.

To achieve the complication in her artwork and express her voice on feminism, Cindy Sherman employs slight changes in backgrounds of famous film settings to speak positively of women: they are not accessories of males, but they are just as intelligent, as calm and logical, and as independent, and their diversity should be seen instead of being reduced to house-carers and sexual appeals. Cindy Sherman also puts on heavier and heavier makeups in her artistic life to mock at the pursuit of the unhealthy beauty forced by males and to expose the disgust towards sexual detritus by emphasizing on otherness. What's more, Cindy Sherman as the model in her Untitled Film Stills series presents herself as vulnerable, innocent, or unaware and in private settings like bathrooms or bedrooms to confront the viewers with an uncomfortable feeling of voyeurism and leads the viewers to question the current situation. With all these masterful methods, Cindy Sherman successuly gets her works out of the comment of a depthless use of pastiche, a comment attributed to most postmodern works. Rather than spreading hollow superficiality and emptiness in the society, Cindy Sherman continues to investigate gender power structures, to confront stereotypes related to identities, and to call for the public to reflect on and change the issues.

References

[1]. Alexander, K. J. (2019). “The Films That Influenced Cindy Sherman's 'Untitled Film Stills' Series.”Retrieved from https://www.dazeddigital.com/art-photography/article/45267/1/the-films-that-influenced-cindy-shermans-untitled-film-stills-series.

[2]. Brigitte Bardot in Contempt. (1963). Retrieved from https://slate.com/culture/2013/10/the-coolest-movie-of-all-time-is-jean-luc-godards-contempt.html.

[3]. Dr. Shana.G and Dr. Beth.H. (2015). "Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #21," in Smarthistory. Retrieved from https://smarthistory.org/cindy-sherman-untitled-film-still-21/.

[4]. Jameson, F. (1983-1998). In The Cultural Turn, 7–11.

[5]. Mary B. L. (2015). "Cindy Sherman, Untitled #228," in Smarthistory, Retrieved from https://smarthistory.org/cindy-sherman-untitled-228/.

[6]. Loren (Left) in the Film La Ciociara. (1960). Retrieved from https://www.artlovingitaly.com/la-ciociara-two-women-sophia-loren/.

[7]. Mulvey, L. (1991). In A Phantasmagoria of the Female Body: The Work of Cindy Sherman.

[8]. Schjeldahl, P. and Phillips, L., Sherman, C. (1987). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, p.15.

[9]. Sherman, C. and Frankel, D. (2003). Cindy Sherman: The Complete Untitled Film Stills. London: Thames & Hudson.

[10]. Sherman, C. (1985). Fairy Tales 1985. Retrieved from https://www.caviar20.com/products/cindy-sherman-fairy-tales-photograph-1985.

[11]. Sherman, C. (1977). Untitled Film Still #2. New York. the Museum of Modern Art.

[12]. Sherman, C. (1978). Untitled Film Still #13. New York. the Museum of Modern Art.

[13]. Sherman, C. (1978). Untitled Film Still #25. New York. the Museum of Modern Art.

[14]. Sherman, C. (1979). Untitled Film Still #34. New York. the Museum of Modern Art.

[15]. Sherman, C. (1979). Untitled Film Still #35. New York. the Museum of Modern Art.

[16]. Sherman, C. (1981). Untitled #96. New York. the Museum of Modern Art.

[17]. Sherman, C. (1983). Untitled #123.1983. New York. the Museum of Modern Art.

[18]. Sherman,C., and Goldsmith, D. (1933). “CINDY SHERMAN.” Aperture, no. 133 (1993): 34–43. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/24471695.

[19]. Sherman, Cindy, and Larry Frascella. “Cindy Sherman’s Tales of Terror.” Aperture, no. 103 (1986): 48–53. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/24471935.

[20]. Sussler, Betsy, and Cindy Sherman. “An Interview with Cindy Sherman.” BOMB, no. 12 (1985): 30–33. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40423120.

Cite this article

Zhang,H. (2023). Cindy Sherman’s Construction of Female Identity —— a Practice more than Depthless Pastiche. Communications in Humanities Research,2,582-590.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Educational Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries (ICEIPI 2022), Part III

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Alexander, K. J. (2019). “The Films That Influenced Cindy Sherman's 'Untitled Film Stills' Series.”Retrieved from https://www.dazeddigital.com/art-photography/article/45267/1/the-films-that-influenced-cindy-shermans-untitled-film-stills-series.

[2]. Brigitte Bardot in Contempt. (1963). Retrieved from https://slate.com/culture/2013/10/the-coolest-movie-of-all-time-is-jean-luc-godards-contempt.html.

[3]. Dr. Shana.G and Dr. Beth.H. (2015). "Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #21," in Smarthistory. Retrieved from https://smarthistory.org/cindy-sherman-untitled-film-still-21/.

[4]. Jameson, F. (1983-1998). In The Cultural Turn, 7–11.

[5]. Mary B. L. (2015). "Cindy Sherman, Untitled #228," in Smarthistory, Retrieved from https://smarthistory.org/cindy-sherman-untitled-228/.

[6]. Loren (Left) in the Film La Ciociara. (1960). Retrieved from https://www.artlovingitaly.com/la-ciociara-two-women-sophia-loren/.

[7]. Mulvey, L. (1991). In A Phantasmagoria of the Female Body: The Work of Cindy Sherman.

[8]. Schjeldahl, P. and Phillips, L., Sherman, C. (1987). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, p.15.

[9]. Sherman, C. and Frankel, D. (2003). Cindy Sherman: The Complete Untitled Film Stills. London: Thames & Hudson.

[10]. Sherman, C. (1985). Fairy Tales 1985. Retrieved from https://www.caviar20.com/products/cindy-sherman-fairy-tales-photograph-1985.

[11]. Sherman, C. (1977). Untitled Film Still #2. New York. the Museum of Modern Art.

[12]. Sherman, C. (1978). Untitled Film Still #13. New York. the Museum of Modern Art.

[13]. Sherman, C. (1978). Untitled Film Still #25. New York. the Museum of Modern Art.

[14]. Sherman, C. (1979). Untitled Film Still #34. New York. the Museum of Modern Art.

[15]. Sherman, C. (1979). Untitled Film Still #35. New York. the Museum of Modern Art.

[16]. Sherman, C. (1981). Untitled #96. New York. the Museum of Modern Art.

[17]. Sherman, C. (1983). Untitled #123.1983. New York. the Museum of Modern Art.

[18]. Sherman,C., and Goldsmith, D. (1933). “CINDY SHERMAN.” Aperture, no. 133 (1993): 34–43. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/24471695.

[19]. Sherman, Cindy, and Larry Frascella. “Cindy Sherman’s Tales of Terror.” Aperture, no. 103 (1986): 48–53. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/24471935.

[20]. Sussler, Betsy, and Cindy Sherman. “An Interview with Cindy Sherman.” BOMB, no. 12 (1985): 30–33. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40423120.