1. Introduction

Expressing politeness through language during interaction is a fairly universal phenomenon to all cultures. Every language has its own way of expressing politeness. In Japanese, there exists a set of morphemes and rules for conveying esteem and courtesy. Japanese honorific is the little morpheme that is used when expressing politeness under some certain rules regarding Japanese grammar and sentence structure.

Japanese honorifics vary greatly in forms, which means there are different morphemes applied to different types of sentences. For example, there are honorific morphemes that attach to a verb and morphemes that attach to a noun. So they have to be used differently between a sentence ending with a verb and a sentence ending with a noun. In particular, the paper would focus on honorifics in a sentence with a copula.

In this paper, I want to illustrate how honorifics are involved in copular sentence structure and try to show the structural difference between two types of copular sentences. The paper is organized in the following way.

First, I introduce Japanese honorifics with examples and then illustrate how honorifics manifest themselves in copular sentences.

Next, I present the research questions and assumptions.

Then, I propose an analysis for a copula sentence with an honorific form and a copula sentence without an honorific form.

Finally, I conclude the paper.

2. Examples of Japanese Honorifics

2.1. Honorifics That Attach to Nouns and Verbs

Japanese honorifics are little morphemes that attach to nouns and verbs. They gives extra meanings such as respect and politeness to an expression. Here are the examples of sentences containing honorifics.

(1a) is a sentence without an honorific. (1b) shows a sentence with an honorific prefix “o-” on the noun “henji (reply)”. It is added at the beginning of the noun “henji (reply)” when the speaker is talking to another person for which they express respect.

(1) a. henji arigatou.

reply thank you.

“Thank you for your reply.” [non-honorific form]

b. o-henji arigatou.

HON-reply thank you.

“Thank you for your reply.” [with an honorific on the noun ‘reply’]

(The speaker honors the hearer)

(2a) is a sentence without an honorific. (2b) shows a sentence with an honorific suffix “-masu” on the verb “wara-ttei-ru (laughing)”. It replaces the tense suffix “-ru” of the verb “wara-ttei-ru (laughing)”. The honorific suffix “-masu” is used when the speaker wants to beautify the utterance and show good manners to the listener.

(2) a. Hanako-wa wara-ttei-ru.

Hanako-TOP laugh-PROG-Nonpast.

“Hanako is smiling.” [non-honorific form]

b. Hanako-wa wara-ttei-masu.

Hanako-TOP laugh-PROG-HON.

“Hanako is smiling.”

“The speaker is speaking nicely.” [with an honorific on the verb ‘smile’]

2.2. Honorifics in a Copula Sentence

This paper focuses on the two different forms of copula. One is the non-honorific copula da and the other is the honorific copula desu. Here are the examples:

(3a) shows a sentence with da “be”. This sentence is appropriate in an informal context. For example, when a student is chatting with his/her classmate.

(3b) shows a sentence with desu “be”. Desu in this sentence is a free morpheme (a copula), which is also an honorific. The sentence with desu is appropriate in a formal context. For example, when a student is talking to a professor.

(3) a. Context: A student is chatting with his/her classmate.

Kanojo-wa sannensei da.

She-TOP three-grade-student COP.

“ She is a three-grade-student.” [non-honorific copula]

Context: A student is introducing a classmate to a professor.

Kanojo-wa sannensei desu.

She-TOP three-grade-student COP.

“ She is a three-grade-student.” [honorific copula]

Similarly, (4a) is a sentence with da “be”. This sentence is appropriate in an informal context. For example, when a speaker invites a friend to his/her home and is showing him/her around.

And (4b) is a sentence with desu “be”, which is appropriate in a formal context, such as when a secretary is talking to his/her boss (or other superiors).

(4) a. Context: The speaker invites a friend to his/her home and is showing him/her around.

Kore-wa watashi-no heya da

This-TOP 1-GEN room COP

“This is my room.” [non-honorific copula]

b. Context: A secretary is talking to his/her boss (or other superiors)

Kore-wa watashi-no heya desu

This-TOP 1-GEN room COP

“This is my room.” [honorific copula]

Here is another pair. (5a) presents a sentence with da “be”. As mentioned above, an honorific-free sentence is appropriate in an informal context, where, for example, an employee is talking to his/her familiar coworkers or inferiors.

And a sentence like (5b) that has desu “be” is suitable in a formal context where, for example, a TV host is making comments in front of an audience.

(5) a. Context: An employee is talking to his/her familiar coworkers or inferiors.

Yuka-wa kirei da

Floor-SBJ clean COP

“The floor is clean.” [non-honorific copula]

b. Context: A TV host is making comments in front of an audience.

Yuka-wa kirei desu

Floor-SBJ clean COP

“The floor is clean.” [honorific copula]

It should be noted that sentences without desu or da are ungrammatical, as shown in example (7) with (6) as a contrast:

(6) Kare-wa koukousei desu/da.

He-TOP senior school student is.

(7) *Kare-wa koukousei.

He-TOP senior school student

3. Research Questions and Assumptions

The assumption that I make is that the underlying structure of a sentence is linked with interpretation. Therefore, I assume whenever there is a difference in meaning, it is reflected in the structure. For example, questions and declarative sentences have different meanings and are used in different contexts with different purposes, and for these different sentences I assume they differ in syntactic structure (i.e.declarative sentences have syntactically different structure from questions). Then a question arises: how do we explain the meaning differences between copula sentences with desu and da in terms of syntactic structure?

From the data in the previous sections, we have seen that desu and da are used in different contexts, namely they are appropriate in different discourse situations. The sentence with desu and the sentence with da do not share the same meaning since they are conveying different information beyond the surface string of words.

Given the assumption about the link between syntax and interpretation, the prediction is that one Japanese copula sentence with da and one with the honorific desu do not actually have the same underlying syntax, though at the surface level, they look almost identical except the form of the copula. We can assume that copula sentences with desu/da are structurally different.

At this point, one may argue that the difference we observe in Japanese copula sentences above has nothing to do with syntax. The difference could presumably be a matter of semantics or the context but is unrelated to the structure of the sentence. Because if we look at the data listed above, the structures seem to be totally the same. It may be argued that it is something about interpretation, something that is directly linked to semantics, not syntax.

Therefore, in the following parts, I am going to explain the meaning differences between copula sentences with desu and da by conducting analysis on their syntactic structure.

4. The Analysis

I am going to conduct the generative syntactic analysis by showing the derivation of the tree of a Japanese copula sentence Hanako-wa gakusei desu/da “Hanako is a high school student”, based on the theoretical perspective that the initial tree structure of a sentence shows the deep structure, and the deep structure undergoes certain movements before we get the correct surface string [1]. I will begin by showing the derivation with desu, and then the derivation with da.

4.1. Derivation with desu

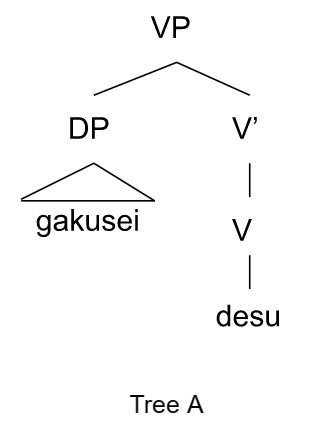

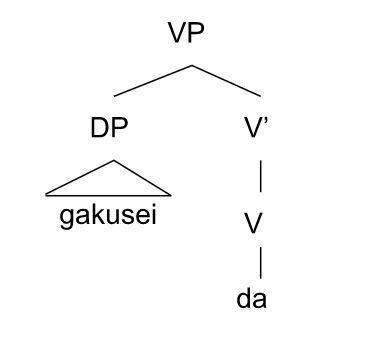

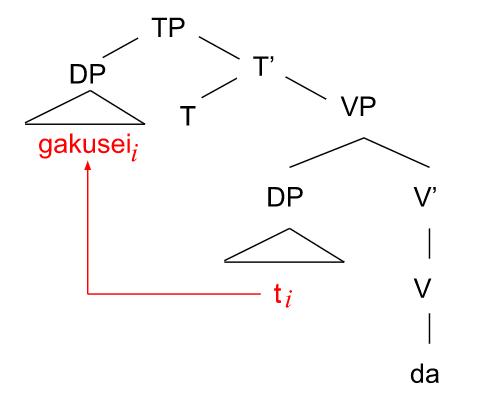

First, I assume the copula desu is in V. Second, I assume that gakusei “student” is a subject that starts in the specifier of VP [2], with Hanako-wa “Hanako-TOP” to be merged later. (as Figure 1 shows below)

Figure 1: Gakusei is in spec of VP and desu is in V.

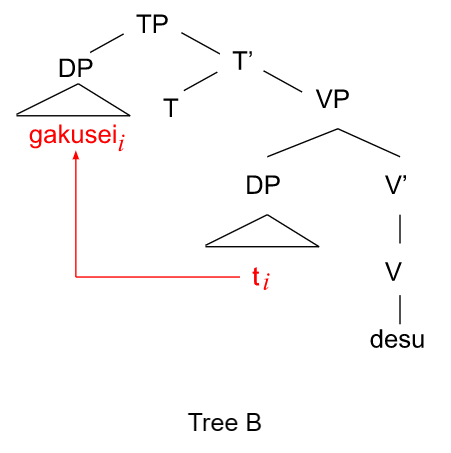

Then we merge T with VP. To satisfy the EPP feature [3] on T, I assume that gakusei “student” moves from the specifier of VP to the specifier of TP. (as Figure 2 shows below)

Figure 2: Gakusei moves from spec of VP to spec of TP.

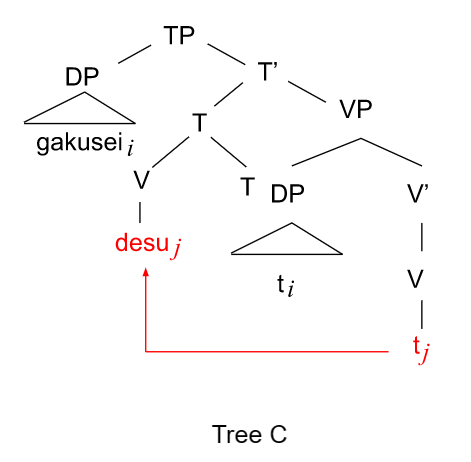

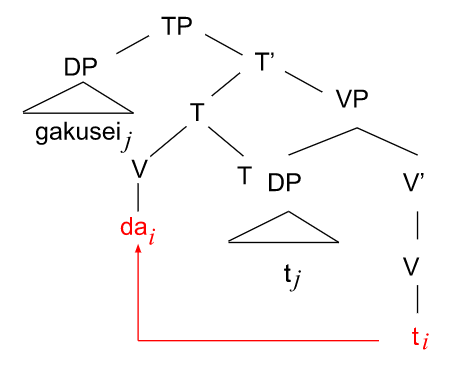

I then assume desu first moves to the T layer to get its tense feature checked, as is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Desu moves to T layer to get its tense feature checked.

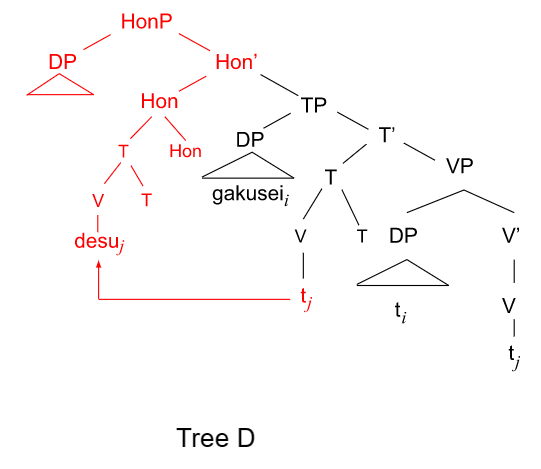

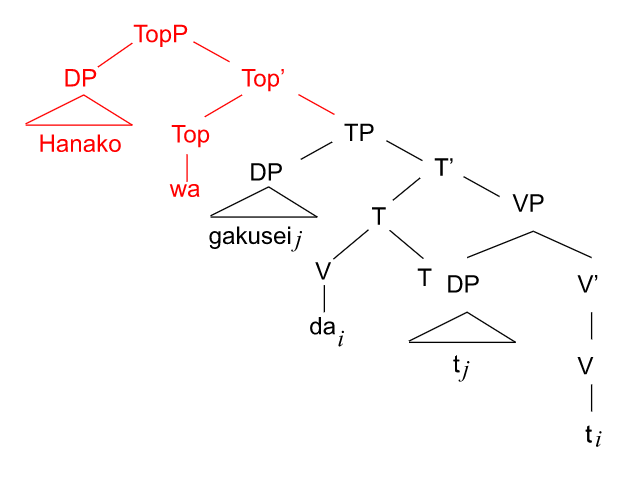

Next, I will assume that politeness can be reflected by the syntax of a sentence and that politeness is a grammatical category encoded into the system of the sentence. I assume that the sentence with desu has the “honorific layer” (HonP) [4]. The head of this projection, namely Hon, gets activated by desu moving to it to get its “politeness” feature checked, as is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Desu moves to the head of HonP to get its “politeness” feature checked.

Now it is the HonP that requires a specifier. To satisfy the EPP feature [3] on Hon, a closest phrase has to move to the specifier of HonP. And the closest phrase is gakusei “student”. So I internally merge gakusei “student” from the specifier of TP to the specifier of HonP. (as is shown in Figure 5 below)

Figure 5: Gakusei moves from spec of TP to spec of HonP.

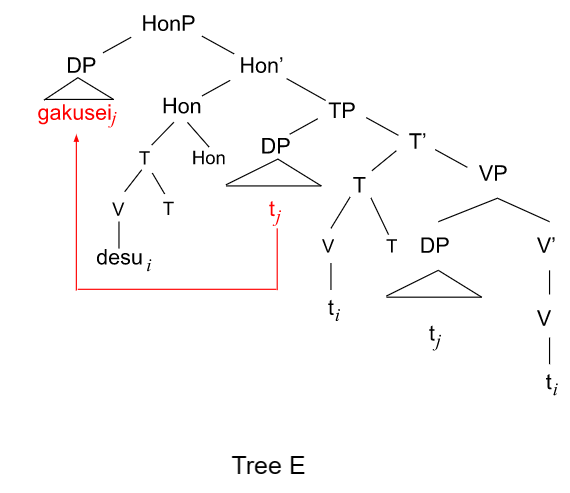

In Japanese, wa is a topic marker. Therefore, I assume Hanako is the topic of the sentence. According to Rizzi, topics are located higher in a tree [5], hence I assume that there is a “topic layer” (marked as TopP) activated in a sentence with the topic marker wa located under Top. To satisfy the EPP feature [3] on Top, I externally merge Hanako in the specifier of TopP. (As Figure 6 shows below).

The complete derivation in Figure 6 translates into the correct linear order, namely, Hanako-wa gakusei desu. “Hanako is a student.”

Figure 6: Hanako is externally merged in spec of TopP.

4.2. Derivation with da

In the following parts, I would like to switch to the analysis of a sentence with da.

Similar to the previous analysis on the polite sentence with desu, first I assume the copula da is in V. Second, I assume that gakusei “student” is a subject that starts in the specifier of VP [2]. (as Figure 7 shows below)

Figure 7: Gakusei is in spec of VP and da is in V.

We merge T with VP. And I assume that gakusei “student” moves from the specifier of VP to the specifier of TP to satisfy the EPP feature [3] on T, as is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Gakusei moves from spec of VP to spec of TP.

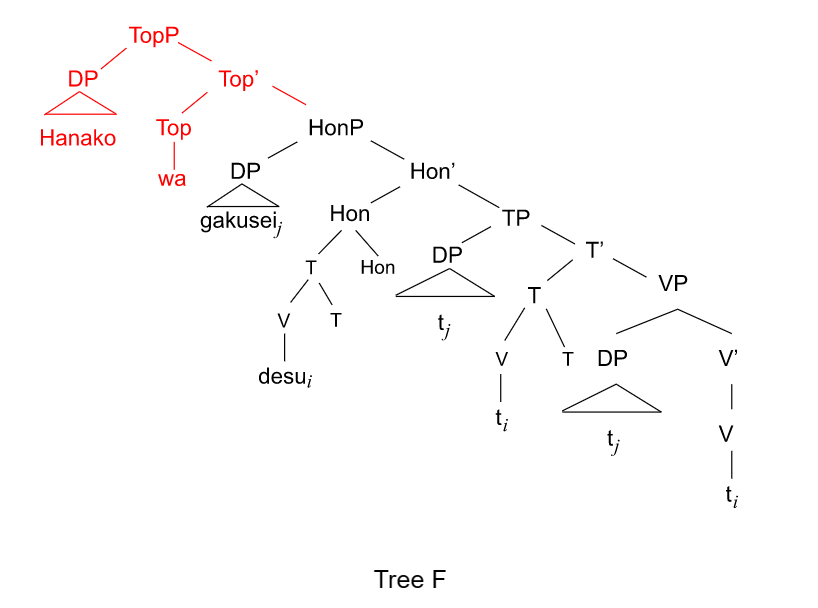

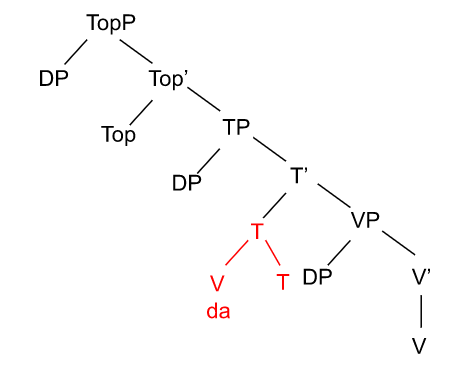

Then I assume that da moves to T to get its tense feature, as is shown in Figure 9 below. However, the HonP is not activated in this case, because da is not an honorific (copula), thus I assume that da stops in T.

Figure 9: HonP remains inactivated and da moves to T.

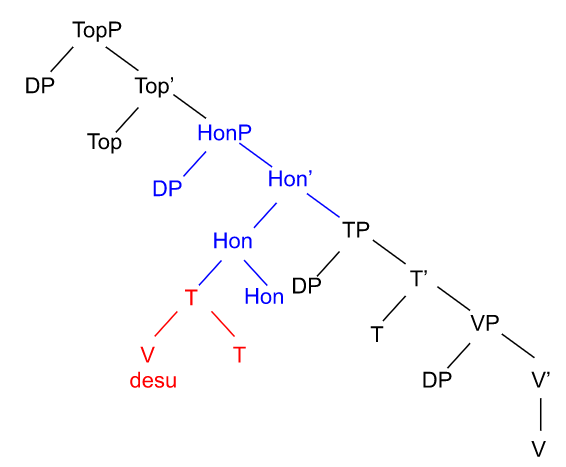

Finally, Hanako is the topic of the sentence. Therefore, I merge Top with TP and put Hanako in the specifier of the TopP (as is shown in Figure 10).

The complete derivation in Tree d translates into the correct linear order, namely, Hanako-wa gakusei da. “Hanako is a student”.

Figure 10: Hanako is externally merged in spec of TopP.

5. Presentation and Summary of Results

On the basis of the analysis above, we can make a summary as follows:

The hierarchical structure of a sentence with desu and a sentence with da can be shown in Figure 11:

Figure 11: The sentence with desu has a bigger structure in the left periphery.

As we can see from Figure 11, the sentence with desu has more structure activated than the sentence with da. There is an honorific layer motivated in the sentence with desu, while in the sentence with da, the honorific layer remains inactivated.

Moreover, the copula in the sentence with desu is “higher” than the sentence with da. In the sentence with desu, the copula is in the HonP layer, whereas in the sentence with da, the copula remains in the TP layer.

Therefore, besides the difference in the amount of structure between a sentence with an honorific copula and a non-honorific copula, another interesting thing that we can observe from the analysis is the position of the verb in Japanese. In the case of languages with tense morphology such as English, Italian or Russian, the verb usually moves as high as T (or even higher) to get the tense feature and inflection morphology, yet it is possible that Japanese verb actually also moves higher than T, considering that Japanese language has honorific forms.

Therefore, based on the analysis above, we can assume that in Japanese, verbs are allowed to move even higher than T. This is because Japanese verbs have honorific morphology that carries politeness information. And the position of tensed verbs in Japanese is left for further exploration.

6. Conclusion

In the analysis conducted above, I showed that one Japanese copular sentence with da and one with the honorific desu do not actually have the same underlying syntax. Here are the differences in the inner structure between a sentence with desu and a sentence with da reflected from the analysis:

A copular sentence with desu has more structure than a copular sentence with da. In a sentence with the honorific copula desu, there is an honorific layer activated. In contrast, in a sentence with the normal copula da, there is no honorific layer activated, which shows that a copular sentence with da has less underlying structure than a sentence with the honorific copula desu.

Besides the main difference in structure, the analysis points to a different position of honorific “be” and a non-honorific “be”. In a copular sentence with desu, the verb moves higher than the TP layer. By comparison, the verb moves as high as the TP layer in a copular sentence with da. This also draws our attention to the position of verbs in a Japanese sentence.

The syntactic analysis proposed above shows how different morphological forms of “be” are connected to different social contexts and grammatical structures and convinces me that we should start teaching honorifics with copular sentences. It is better for beginners learning Japanese as the second language to start learning honorifics from copular structure than from the rules of affixation. I suggest that modern Japanese second language education should prioritize the introduction to copular structure so as to enable Japanese honorifics to be taught in a more vivid, impressive and effective way.

In the analysis conducted above, I assumed that the honorific layer is above the TP layer. However, the exact location of HonP in Japanese syntax is left for further investigation.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Daniela Culinovic, who had led me into the door of linguistics research field and gave me a lot of inspirations and informative instructions concerning this paper.

References

[1]. Sportiche, D et al. (2013). An Introduction to Syntactic Analysis and Theory.Wiley-Blackwell.

[2]. Koopman, H. and Sportiche, D. (1991). The position of subjects. Lingua, 85, 211–258.

[3]. Chomsky, N. (1981). Lectures on Government and Binding: The Pisa Lectures. Dordrecht: Foris.

[4]. Lee, Doo-Won. (2014). Two Positions of Honorific Phrases in Korean Long Form Negation. Studies in Linguistics, 31, 179-199.

[5]. Rizzi, L. (1997). The fine structure of the left periphery. In Haegeman, Liliane (Eds.), Elements of grammar, 281–338. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Cite this article

Wang,M. (2023). The Internal Structure of Copular Sentences with desu and da in Japanese. Communications in Humanities Research,10,183-192.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Educational Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Sportiche, D et al. (2013). An Introduction to Syntactic Analysis and Theory.Wiley-Blackwell.

[2]. Koopman, H. and Sportiche, D. (1991). The position of subjects. Lingua, 85, 211–258.

[3]. Chomsky, N. (1981). Lectures on Government and Binding: The Pisa Lectures. Dordrecht: Foris.

[4]. Lee, Doo-Won. (2014). Two Positions of Honorific Phrases in Korean Long Form Negation. Studies in Linguistics, 31, 179-199.

[5]. Rizzi, L. (1997). The fine structure of the left periphery. In Haegeman, Liliane (Eds.), Elements of grammar, 281–338. Dordrecht: Kluwer.