Abstract: The media has, for decades, been a tool through which the objectification and sexualization of women have been perpetuated. The research question pertains to whether East Asian magazines also encourage the perception of women as sexual objects. This research investigated four East Asian magazines, namely, VIVI, Korean Allure, Chinese Beauty, and Chinese ELLE, using the semiotic analysis to determine the extent to which the cover models’ clothing style and make-ups were used to sexualize and objectify East Asian women. Although some countries like Korea have tried to eliminate women's fetishization, others still insist on promoting sexualized images of women to protect their magazine sales and because of the power of the male gaze. The author argued that fashion magazine should be used more efficiently as a platform where women are empowered to express themselves outside the stereotypical sexualization and objectification of women perpetrated by the male gaze.

1. Introduction

Women have been objectified and sexualized through the media for decades, particularly in Western media and society. Hollywood has popularized the archetypes of East Asian women, such as the overly emotional, delicate, and submissive China Doll, which hypersexualizes and infantilizes the East Asian woman [1]. Images of women maintained through popular media are hinged on their sexuality, which is measured through the male gaze. In Western media, the Asian woman is hypersexualized and infantilized to satisfy White men’s desires, while in East Asia, the same occurs to gratify the patriarchy. The fetishization and sexualization of women is a dangerous trend because it affects how people view women, how they view themselves, and perpetuates violence against women.

Advertisements in fashion magazines sexualize and objectify women by featuring them in scanty clothing, red pouted lips, erotic and tantric poses. In contrast, some of them go all out and feature them naked [2]. Some of these ads are not even remotely related to sex, as seen in the Kohler kitchen faucet advertised by a naked woman. Western magazines are not unique in their sexual imagery of women, as evidenced by the review of the cover pages for four East Asian magazines. These magazines insist on fetishizing women by perpetuating gendered ideals that appeal to their men. For instance, Japanese and Chinese magazines feature women with exposed body parts to attract male consumers' attention. In contrast, Korean magazines infantilize women to satisfy men's fetish to protect women [3]. The characterization of women based on their sexuality to increase the sale of fashion magazines in East Asia promotes their sexualization and objectification to cater to the male gaze.

Women rely on fashion magazines to update them on trends and products that could improve their social status [4]. Thus, fashion magazines can play a substantial role in the empowerment of women. Instead, their representation of women primarily through a sexual lens denigrates them and keeps them under the influence of the male gaze. This study uses semiotic analysis to investigate the objectification and sexualization of women in East Asia, particularly the role of fashion magazines in women empowerment and social status. Rather than promoting the sexualization and fetishization of women in East Asia, fashion magazines should offer women a platform to express themselves without being limited by the male gaze.

The research will involve a semiotic analysis of four East Asian magazines: i) VIVI, a top Japanese fashion magazine, ii) Korean Allure magazine, iii) Chinese Beauty magazine and the Chinese ELLE fashion magazine. These will provide a perspective on the type of women’s clothing and make-up advertised on the cover of these fashion magazines and the messages they represent. The next section will analyze findings regarding the clothing style and make-up. The study finds that Korea has made substantial strides in reducing female objectification by encouraging comfort and “innocent” wear [5]. However, the clothing styles in Japan and China, and the make-up trends retain sexual and fetishized depictions of women. East Asia is making some progress towards better representation of women, but a lot remains to be done regarding eliminating the significance of the male gaze.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Theory of Semiotics

Semiotics refers to the science of sign systems and the processes through which an individual understands a phenomenon and organizes it mentally. The theory implies a relationship between a sign as a representation of a referent and a meaning [6]. The concept enables the development of a means to convey an understanding of a symbol. Zlatev [6] observes that such an argument implies that the interpreters of the signs that reflect the elements of an intended object are the people. Besides, the interpretation process for such details involves the aspects of designative, which guide an interpreter to the purpose, appraisive that highlights the qualities of an object and prescriptive that direct response in distinct ways.

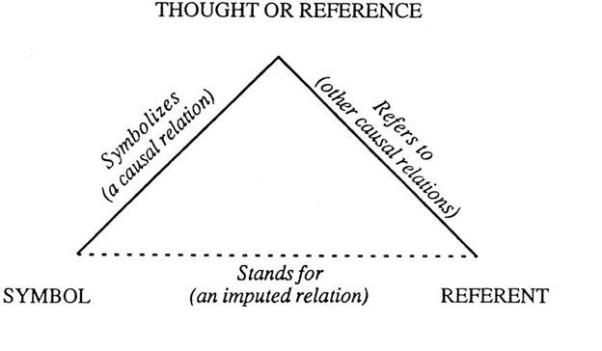

Moreover, the theory involves various semiotic tools that ensure an understanding of the intended meaning of a communication. Such include the semiotic triangle, Cameron Shackle's finite semiotics, and cognitive semiotics. According to Semetsky [7], the tools share a similarity in providing ideas on how to go about understanding an object’s maze meaning. The only difference is the context of application based on ways of transmission. Sanders Peirce’s is the most effective of the semiotic tool for understanding fashion and feminism-based issues. The model constitutes of elements demonstrating how a symbol relates to an objected it represents [7]. In such regard, there are three linked aspects of a sign in the triangle. The symbol connects to the referent through thought as the internal representation. The production process involves an individual conceptualizing the referent, thereby forming an internal image before verbalizing it as a symbol. Semetsky’s study adds that the comprehension involves a special parsing the sign, thus retrieving a representation and then interpreting as a referent. Such indicates the mark symbolizes a thought as the intended behavior that refers to and stands for the referent. The triangle in the context of fashion captures the processes through which semiotic aspects influence individual perceptions of women. Therefore, semiotics provides a way of viewing the East Asia society and understanding how some elements such as culture massively control us unconsciously.

In fashion, the semiotics triangle would apply distinctively. Such is through enabling an understanding that women's fashion style involves different layers of meanings and signification. According to Kuruc [8], such would come with diversified complexity as informed by the purposes of the fashion signs involved. Besides, this also extends to the unpredictable ease of understanding where individuals perceiving fashion in the context of social status and empowerment becomes directed by a particular reference frame. The semiotics triangle would, therefore, demonstrate how fashion style becomes subject to instances of misinterpretation.

Figure 1: Semiotic Triangle. Source: semanticsscholar.org.

2.2 The Relationship between Fashion and Feminism

According to Fung [9], feminism and fashion share a troubled relationship. In this context, the style has a history of playing the role of a budge in portraying feminism, especially cultural identity. Women tend to dress in specific ways based on the influence of femininity. Such helps in understanding the link between the outward appearance of a woman and the essential femininity. Titton's [10] study agrees by arguing that western society's promotion of clothing and make-up fashion in this context also paints a picture of how style promotes femininity through consumerism. The observation, therefore, brings out the objectification and sexualization of women in fashion sense.

In Asia, the relationship defines the depiction of most women in society. The clothing style and application of make-up play a fundamental role in the objectification and sexualization of women. According to Bertrand [5], such happens through the development of an appeal intended to draw a targeted audience's attention. The China and Japan fashion market in this context focuses on the revealing fashion sense meant to emphasize a sexual appeal. On the other hand, the Korean market practices less of the revealing fashion by focusing on comfortable wear. Bertrand [5] adds that make-up is also a fundamental aspect in style in the sense of sexualizing appearance where China and Korea encourage the use of lipsticks while Japan focuses on blushes in heightening sexual appeal. Such depicts the diverse objectification of women in fashion.

Fashion magazines are part of the leading platforms in the Asian fashion market used in driving the agenda of objectifying and sexualizing women through fashion. The approaches, primarily through the style of cover models, still have a minor effect on the male gaze, which remains a dominant aspect in markets like Korea, China, and Japan. Some of the leading magazines in women fashion that help with the depiction of such fashion content are VIVI, the top Japanese fashion magazine, Korean Allure magazine, Chinese Beauty magazine, and the Chinese ELLE fashion magazine.

3. Analysis

3.1 Clothing style on fashion magazine

From an overall perspective, an evaluation of the Chinese fashion magazine ELLE shows that the representation of clothing styles and beauty standards is diversified but focuses on sexiness in China. Apart from the dresses, skirts, and other typically ladylike women clothes, drop shoulder blazers, cargo trousers, jeans are also found on Chinese ELLE magazine covers. Nevertheless, exposed body parts are still widely used in no matter what kind of clothing styles. For example, the March 2019 ELLE magazine cover features a beautiful young girl dress in a grey suit jumpsuit. The cover model is the “businesswomen style” look. Although the cover model is dressed in an untypical woman clothing, one of her shoulders is naked, which helps create a sexy and erotic image of a woman. The naked shoulder can be seen as a sign, which evokes the magazine readers’ thoughts that the exposed body parts are closely connected to the concept of women's beauty in China. The readers’ thoughts are reference to the fact that the occurrence of the diversified clothing styles indeed does not change the status of women in China. Women are still viewed as sexual agents whose greatest value is their sexual appeal. Admittedly, women are taking charge of their representation in Chinese media -- they got more freedom to choose or redefine their clothes -- which already made a great evolution, but they are still trapped in the realm of looking sexy, perhaps to satisfy the male gaze. Despite the evolution, the image of women in Chinese print media is still subject to objectification.

Figure 2: Source: ELLE Magazine

To some degree, Japanese magazines hold similar beauty ideals like those in China, as almost all the VIVI magazine covers encapsulate the idea of women beauty in Japan– looking sexy and gentle. Similar to Chinese fashion magazines, the clothing styles of Japanese fashion magazine also emphasizes on the exposed body parts (shoulders, legs, and thighs). However, differing from the diversified clothing styles in China, Japan has a relatively monotonous clothing style. Out a total of twelve VIVI magazine issued in 2019, six magazine covers featured girls dressed in knitwear, and five covers show models wearing cropped camisoles or tank tops. Also, if the model is dressed in a long-sleeved knitwear top, her lower body will usually be naked. An example is the January 2019 VIVI magazine cover which features a model with the “rocking the cowgirl” look: wearing a black high-neck knit with shorts and animal printed boots. Similarly, the September and March 2019 VIVI magazine covers also use the same clothing style. It is clear that naked thighs can be seen as an essential sign, which helps create ideal sexual imaginations and elicit thoughts of sexual desire in reference to Japanese men and their sexual fetishes. However, from another perspective, soft knits or cropped camisoles can also be seen as a sign. Wearing soft knits gives people a feeling of gentleness, and dressing in cropped camisoles creates an image of purity and innocence. Therefore, those clothes evoke the magazine audiences' thoughts to protect the girls on the magazine covers. Simultaneously, the monotonous clothing style on the VIVI magazine covers can be seen as a referent for the girls' perception in Japanese society in which they are expected to be pure, gentle, cute and available to fulfill men's sexual desires. By extension, the erotic appeals on the magazine covers are closely connected to the concepts of beauty in Japanese society where young girls are extremely sexualized by a system where police ignore the plight of girls in soaplands and men frequent hostess bars [11]. While the girls featured in the VIVI magazine differ in their overall styles, the dominant feature is that they are gentle, young, and delicate enough to fulfill the men's desire to protect women in Japanese society.

Figure 3: Source: VIVI Magazine

Based on the Korean magazine Allure, the representation of women in Korean mainstream media differs from other countries such as China and Japan [5]. The women on the Allure magazine covers are dressed in a more conservative clothing style. Simultaneously, the clothes are connected with more diversified, vivid colors, making the overall dressing style more fashionable, girlish, and innocent. In contrast with the exposed body dressing styles in China and Japan, Korean magazine Allure utilizes elements of maxi dresses and oversized shirts or blazers in their covers. Out of the seven covers (March, April, May I&III, June, and July I&II in 2019), models are wearing maxi dresses with a relative loose cut and long sleeves. Out of the four covers (May II, August, September, and October 2019), girls are dressed in oversized blazers.

On the other hand, the bright colors of the clothes quickly catch the audiences' eyes. Take May 2019 III as an example, three models dressed in a maxi dress with mint green, coral pink, and aqua blue leopard print colors. Also, on the covers of Allure magazine May II and August 2019, women are wearing oversized blazers with diversified colors such as khaki, baby pink, tiger lily, baby blue, and lilac. The vivid colored maxi dresses and oversized blazers indeed can be viewed as a sign, which expresses the thought that Korean women should be conservative, understanding, and keep being an image of a young, innocent girl at the same time. Beyond that, the colored dress and blazers are also a referent. They reiterate the Korean high-standard perception of women as intelligent, fashionable, and, most importantly, keeping energetic and young.

3.2 Make-ups of cover models

From the perspective of cosmetics, Chinese fashion magazine covers usually use flashy eyes make-ups and red lipsticks to build a sexy image of women. Flashy make-up can easily impress people, especially the eyes since eyes play an essential role in daily communication. Also, based on the color theory, red is closely connected with passion and desire for sexuality [12]. Take Chinese fashion magazine the BEAUTY as an example; the cover models on seven issued magazine covers in 2019 are wearing red lipstick to reiterate the need for women to be sexy [5]. On the other hand, on the BEAUTY cover of December 2019, the model is wearing volume-curved eyelashes and winged eyeliner with heavy eye-shadow on her face. From the examples, the red lipsticks, winged eyeliners, and the curved eyelashes can be viewed as a sign. Those signs transfer information that make-up is used as a tool of revealing women attraction or impressing guys to the audience. Over time, the Chinese audience forms a link between make-up and sexy women. Make-up becomes a symbol of a woman's beauty and sexuality. The audience's thoughts also refer to that make-up as a symbol of beauty that elicits sexualized appeals in men and extends sexism, a recurrent theme in the Chinese beauty context. Admittedly, the same as the dressing style, different make-up styles also occur on the covers of Chinese fashion magazines the BEAUTY. Nowadays, women are trying to redefine the role of wearing make-up in Chinese society; make-up is used to symbolize power and individuality. However, in the Chinese context, beauty is carved in Confucian ideals that place women in conservative family duties at men's service. Hence, the mainstream culture still puts women wearing make-up in the place of impressing others.

Figure4: Source: BEAUTY Magazine

In contrast with the Chinese magazine’s cosmetic style, the models on Japanese VIVI magazines wear more nude looks, which give the audience a fresh and natural sense. At the same time, the magazine also widely uses the orange color scheme in eyeshades, blushers, and lipsticks of the girl models. In the color theory, the orange is a youthful and energetic color that easily conveys warmth and joy to the people [13]. For instance, in the 2019 VIVI magazine covers, out of nine covers' models are wearing nude looks. The make-up emphasizes the sense of natural and fresh by using the natural eyebrows' shapes, the light inner eyeliners, and nude glossy lipsticks. Also, take the 2019 May VIVI magazine cover as a specific example; the girl is wearing the light eyes make-up, orange blushes with neat hair bangs. The nude eye make-up and orange blushes can be viewed as a sign. Those signs have always been the ablest to stimulate men's thoughts of protection desires to girls in Japanese society. The extensive usage of those signs also shows a clear indication of female objectification and sexualization of women in Japanese magazine covers. The cover on VIVI magazine features a typical girl's make-up and signifies the ritualization of subordination on the woman's part. Print media magazines tend to portray women as defenseless, powerless and accepting subordination to illustrate the power imbalance between men and women.

Figure 5:Source: VIVI Magazine

The Korean magazine focuses on portraying cosmetic facial beauty through glitter-flecked skin and perfect facial elements. That is because the Korean concept of beauty is a pretty face, as noted in the study of the predictors of cosmetic surgery among Korean adolescents. The Korean Allure magazine covers show that people will use make-up as a tool to conceal their "imperfect" facial elements. Take the 2019 August Allure magazine cover as an example; the models wear light eyes make-up and relative dense lip color. By doing this, instead of concentrating on the models' single-fold eyelids, which are viewed as imperfect or unattractive facial elements in Korean culture, the audience will first look at their lips. The perfect overall make-up can be viewed as a sign that conveys the thought that perfect facial consciousness is the core representation of beauty in Korean society to the audience, as identified by Kim et al. [14]. The sign also served as a referent, indicating that the perfect faces presented in all 13 issues of Allure magazine signify beauty and internalized objectification. They create images of sentimentalism among Korean men and drive a narrative of the essentiality of body appearance and facial perfection in the Korean culture. Like the objectification in Japan and China, the magazine covers in Korea sell an idea of beauty confined through small scales. That creates a sense of ambition among young women as they seek to achieve perfect facial appearance to appease men, in the case of heterosexual women.

Figure 6: Source: Allure Magazine

4. Conclusion

Claiming that fashion magazine provides a platform for the elevation of East Asian women conveniently ignores the gendered image of women. The magazines might have challenged the open objectification and sexualization of women, but the male gaze remains, albeit with reduced power. Notably, the male gaze remains a dominant force in China and Japan, but Korea’s fashion styles have much moved away from the objectification of women [5]. These shifts emerge in how beauty magazines present female cover models where both the make-up and fashion styles either deviate or conform to the stereotypical representation of women.

From a Foucauldian perspective, the objection and sexualization of women in fashion magazines only perpetuate gender biases. In China and Japan, magazines emphasize the exposure of body parts where the sexual appeal increases sales. Conversely, Korea has reduced female objectification with most magazines like Allure, encouraging comfortable and innocent wear [5]. As this discussion has shown, all three East Asian nations have retained make-up styles that present women as inferior to men. Japanese women use orange blushes that not only sexualize their appearance but also create a drive for men to protect women. Both China and Korea focus on lipsticks and eye shadow styles that heighten the sexual appeal of women's faces. What this suggests is that the male gaze plays a critical role in determining acceptable norms of make-up.

Despite the global push for equality, women are still perceived to be objects that fulfill sexual desires. In the fashion sector, magazines in Japan and China insist on exposed body parts to their magazines to increase the clientele base by attracting their attention since it fulfills their sexual fetishes [11]. Similarly, Chinese women are trying to take charge of how they are represented in the media. However, they are still trapped in satisfying the sexual desires of the male gaze [15]. However, many years it may take that women's image in Chinese print media will always be subject to objectivities. Sexualizing women degrades their worth and reinforces structures that exclude them from socioeconomic processes.

The examples from Korea and Japan illustrate that the empowerment of women through fashion should deal with the sophisticated power play created by the male gaze. If all clothing and make-up styles are primarily meant for the comfort and Allure of the woman, then several questions should be asked. How is the male gaze allowed to influence fashion styles, and why should models impress patriarchal structures? If fashion is personal, how do social norms and consumerism affect sexuality in the presentation of women fashion figures? Combining feminist and Kantian thinking makes a case for the dignified treatment of women. Women should not be used to satisfy the male gaze or increase the volume of sales. Here, objectification and sexualization of women through fashion treats them as a means to an economic gain. Ultimately, fashion should provide a platform where women can express themselves without conforming to stereotypical images where the male gaze sexualizes and objectifies female models in fashion magazines.

References

[1]. Lee, J. (2018). East Asian" China Doll" or" Dragon Lady"?. Bridges: An Undergraduate Journal of Contemporary Connections, 3(1), 2.

[2]. Freire, N. A. (2014). When luxury advertising adds the identitary values of luxury: A semiotic analysis. Journal of Business Research, 67(12), 2666-2675.

[3]. Xiao, L., Li, B., Zheng, L., & Wang, F. (2019). The relationship between social power and sexual objectification: Behavioral and ERP data. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 57.

[4]. Luo, X. (2008). WOMEN'S FASHION MAGAZINES IN JAPAN: Women vs. Women's Fashion Magazines in Relation to Self-image Creation and Consumption.

[5]. Bertrand, D. (1988). The Creation of Complicity A Semiotic Analysis of An Advertising Campaign for Black & White Whisky. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 4(4), 273-289.

[6]. Zlatev, J. (2012). Cognitive semiotics: An emerging field for the transdisciplinary study of meaning. Public Journal of Semiotics, 4(1), 2-24.

[7]. Semetsky, I. (2019). Visual Semiotics and Real Events. Video Journal of Education and Pedagogy, 4(2), 90-110.

[8]. Kuruc, K. (2008). Fashion as communication: A semiotic analysis of fashion on ‘Sex and the City’. Semiotica, 2008(171), 193-214.

[9]. Fung, A. (2000). Feminist Philosophy and Cultural Representation in the Asian Context. Gazette, 62(2), 153-165.

[10]. Titton, M. (2019). Afterthought: Fashion, Feminism, and Radical Protest. Fashion Theory, 23(6), 747-756.

[11]. Luck, A. (2017). Japan’s Madonna complex: Japan’s contradictory attitudes include highly sexualised images of women and women not being allowed to talk about sex-related subjects. Index on Censorship, 46(1), 22-25.

[12]. Elliot, A. J., & Maier, M. A. (2012). Color-in-context theory. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 45, pp. 61-125). Academic Press.

[13]. Wool, L. E., Komban, S. J., Kremkow, J., Jansen, M., Li, X., Alonso, J. M., & Zaidi, Q. (2015). Salience of unique hues and implications for color theory. Journal of vision, 15(2), 10-10.

[14]. Kim, S. Y., Seo, Y. S., & Baek, K. Y. (2014). Face consciousness among South Korean women: a culture-specific extension of objectification theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(1), 24.

[15]. McKenney, S. J., & Bigler, R. S. (2016). High heels, low grades: Internalized sexualization and academic orientation among adolescent girls. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26(1), 30-36.

Cite this article

Wang,M. (2021). A Semiotic Analysis of the Objectification and Sexualization of Women in East Asia: Exploring the Role of Fashion Magazine. Communications in Humanities Research,1,36-44.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Educational Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries (ICEIPI 2021), Part 2

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Lee, J. (2018). East Asian" China Doll" or" Dragon Lady"?. Bridges: An Undergraduate Journal of Contemporary Connections, 3(1), 2.

[2]. Freire, N. A. (2014). When luxury advertising adds the identitary values of luxury: A semiotic analysis. Journal of Business Research, 67(12), 2666-2675.

[3]. Xiao, L., Li, B., Zheng, L., & Wang, F. (2019). The relationship between social power and sexual objectification: Behavioral and ERP data. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 57.

[4]. Luo, X. (2008). WOMEN'S FASHION MAGAZINES IN JAPAN: Women vs. Women's Fashion Magazines in Relation to Self-image Creation and Consumption.

[5]. Bertrand, D. (1988). The Creation of Complicity A Semiotic Analysis of An Advertising Campaign for Black & White Whisky. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 4(4), 273-289.

[6]. Zlatev, J. (2012). Cognitive semiotics: An emerging field for the transdisciplinary study of meaning. Public Journal of Semiotics, 4(1), 2-24.

[7]. Semetsky, I. (2019). Visual Semiotics and Real Events. Video Journal of Education and Pedagogy, 4(2), 90-110.

[8]. Kuruc, K. (2008). Fashion as communication: A semiotic analysis of fashion on ‘Sex and the City’. Semiotica, 2008(171), 193-214.

[9]. Fung, A. (2000). Feminist Philosophy and Cultural Representation in the Asian Context. Gazette, 62(2), 153-165.

[10]. Titton, M. (2019). Afterthought: Fashion, Feminism, and Radical Protest. Fashion Theory, 23(6), 747-756.

[11]. Luck, A. (2017). Japan’s Madonna complex: Japan’s contradictory attitudes include highly sexualised images of women and women not being allowed to talk about sex-related subjects. Index on Censorship, 46(1), 22-25.

[12]. Elliot, A. J., & Maier, M. A. (2012). Color-in-context theory. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 45, pp. 61-125). Academic Press.

[13]. Wool, L. E., Komban, S. J., Kremkow, J., Jansen, M., Li, X., Alonso, J. M., & Zaidi, Q. (2015). Salience of unique hues and implications for color theory. Journal of vision, 15(2), 10-10.

[14]. Kim, S. Y., Seo, Y. S., & Baek, K. Y. (2014). Face consciousness among South Korean women: a culture-specific extension of objectification theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(1), 24.

[15]. McKenney, S. J., & Bigler, R. S. (2016). High heels, low grades: Internalized sexualization and academic orientation among adolescent girls. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26(1), 30-36.