1.Introduction

Women’s increased involvement in the job market has brought positive changes, yet they still face an unequal burden of unpaid domestic work. Despite the significant economic and educational advancement of women in recent decades, studies show women’s domestic responsibilities haven’t decreased, leading to a dual workload, known as the “second-shift” [1]. Even in gender-equal societies, men contribute significantly less time to household chores [2,3]. This unequal division of labour highlights gender inequality. In addition, unpaid domestic labour is predominantly undertaken by women, but their contribution in this regard is of-ten overlooked, despite its important value to the functioning of society [4]. In this case, society faces challenges in achieving sustainable development and gender equality.

In China, the traditional notion of men as breadwinners and women as home-makers persists, despite more women joining the workforce due to reforms [5]. Women’s increased participation in productive activities has not lessened their burden in social reproduction. Most urban households still uphold the traditional division of household chores and women spend 1-4 times more time on house-work, leading to a dual burden and negative health effects [6,7]. This imbalance may affect women’s well-being, family care and the sustainable development of society [8]. Exhausted unpaid workers are less able to provide good care for their family members, leading to a decrease in overall labor productivity and thus eco-nomic downturn [4]. Therefore, ignoring women’s role in social reproduction risks China’s sustainability. In order to better understand this unequal gender division of labour, the theory of social reproduction emerged. It places gender primarily at the centre of the study, pointing out the significant contribution and oppression of women in social reproduction. Furthermore, the establishment of a paternity leave system can effectively address this issue. Paternity leave will allow men to have enough time to participate in childcare activities, which will enable both genders to share the social reproduction activities more equally, alleviate the burden on women and promote gender equality and sustainable social development.

This paper will first use the theoretical framework of social reproduction to understand the concept of social reproduction and further analyses gendered division of labour that exist in this area. Then, the paperwill present the role of the paternity leave system in addressing the unequal gender division of labour in social reproduction. Next, the paper puts the issue into the Chinese context to analyse the current situation of gender division of labour in domestic work in China. In the following section, by applying comparative policy analysis, the paper will analyse both the successes of Sweden’s paternity leave system and the shortcomings of China’s paternity leave system in dealing with gendered division of labour. Using Sweden as a template and then considering the actual situation in China, the paper hopes to provide practical suggestions for Chinese policy makers. The significance of this study is that, within the theoretical framework of social reproduction, it helps society to recognise that unpaid domestic work, as an important part of social reproduction, plays a crucial role in maintaining the functioning and productivity of society. In addition, the important contribution of women in social reproduction is also seen, as well as the double burden they have been shouldering for a long time. On this basis, this study aims to break down the gender division of labour in social reproduction, promote gender equality in this area, and ultimately contribute to a more inclusive and sustainable society in China.

2.Literature Review

2.1.Theoretical Framework

2.1.1.Social Reproduction Theory

The social reproduction theory emerged to understand the important role of social reproduction which is beyond the production process in the maintenance of labor and capitalism system. Social Reproduction Theory (SRT) defines social reproduction as the set of activities and processes necessary for the maintenance, reproduction, and daily functioning of society [9]. The social reproduction activities cover a wide range of activities including, but not limited to, domestic labor, care work, education, health care, community building, and the production and reproduction of cultural and social norms [9-14]. More specifically, social reproduction activities typically involve three dimensions: physical, physical, emotional, and mental [9,15]. First, ‘physical’ usually refers to behaviors that biologically sustain and reproduce populations. It includes re-productive behaviors; providing the necessities of human life such as food clothing and shelter; and providing services such as child rearing, caring for the elderly and infirm [16]. Second, emotional reproduction activities involve providing emotional care to maintain family and intimate relationships, such as giving care to the elderly and accompanying children in their development [15]. Thirdly, spiritual reproduction activities include cultural and ideological reproduction, which can be done through parents’ education of their children [9,15-17]. SRT emphasises that these social reproduction activities are crucial for the re-production of labor and to support the capitalist system.

However, in the context of the time, the logic and socio-cultural relations of capitalism dominated the functioning of society. Capitalism argues that only labor in the sphere of production can be described as the only legitimate form of ‘work’, while socially reproduction activities that do not circulate in the market cannot be considered a form of work [9,11]. Since social reproduction activities such as caregiving, child rearing, and domestic work usually take place in the private sphere, do not enter the market. Therefore, social reproduction activities are usually ignored and devalued [14,18]. This is in effect denial of the value of unpaid domestic labor performed primarily by women, which contributes to gender inequality and reinforces women’s subordinate position in society. Thus, SRT challenges the existing logic of how capitalism works. SRT asserts that social reproduction and productive activities are interconnected and interdependent, and together they constitute the functioning of society. The production of marketable goods and services and the reproduction of life are interconnected com-ponents of a unified process that are both fundamental to the continuation of society [16,19-22]. For example, domestic work and childcare ensures that the labor force is able to renew and perfect itself and continue from generation to generation, which further allows for the integrity of capitalist production and reproduction. Therefore, the role of social reproduction is significant and should be given the same importance as productive activities. By exposing the hidden dynamics of the private sphere, SRT sought to challenge the traditional capitalist theory and call attention to the importance of social reproduction.

2.1.2.Gendered Division of Labour

The gendered division of labour is an important component of SRT, which contributes to a better understanding of how capitalist societies reproduce and perpetuate existing gender hierarchies and norms. SRT states that women are the main bearers of social reproduction activities and that their contribution in this area is often overlooked. This leads to the exploitation and marginalisation of women. Traditional notions of gender roles define men as the breadwinners, while unpaid domestic labour, including tasks such as childcare, housework, and eldercare, is primarily the responsibility of women [23]. Women, as the main bearers of social reproduction activities, contribute to the maintenance and continuity of society. However, under the operating logic of capitalism, women’s contributions are often unpaid or undervalued, which leads to women’s subordination within the family and society. Federici points out that women’s reproduction labour, including childcare, and domestic work, is considered inferior to productive activities performed by men because they do not participate in market circulation and do not have monetary value [24]. As a result, social reproduction activities have been historically neglected. In this context, SRT emphasizes, on the one hand, the important contribution of women’s social reproduction activities to the functioning and reproduction of capitalist society [9,15,24]. On the other hand, SRT points to the fixed and gendered division of labour in the field of social reproduction and the unpaid nature of domestic work, which together con-stitute women’s long-term economic dependence on men, as the material basis of female exploitation [25-27]. In other words, the gendered division of labour and the unpaid nature of domestic work not only fundamentally devalues and ignores the fruits of women’s labour in the realm of social reproduction, but also further reinforces gender inequality through the economic subjugation of women.

In addition, the exploitation of women is not only economic, but is also reflected in the double burden borne by women. The double burden refers to the fact that with the passage of time, more and more women have flocked into the productive sphere. While participating in paid employment, women are also re-quired to fulfil the responsibilities of unpaid work at home [1,28,29]. This double burden can lead to time constraints, increased stress, and limit women’s opportunities to fully participate in the labor market or pursue career advancement. [1,8]. Kabeer observed that unpaid care work in the home continues to be almost universally assigned to women regardless of their employment status [30]. Research has shown that simultaneously taking on multiple roles, such as that of employee and mother, can lead to excessive stress and poor health outcomes such as obesity and psychological problems for women [7]. In this context, it is particularly important to utilize the SRT framework to break down the gender division of labor and promote the sharing of social reproduction responsibilities between the sexes to alleviate the double burden on women.

2.2.Paternity Leave

SRT has pointed out that the gender division of labour in social reproduction places a double burden on women, both in work and in life. In this context, paternity leave was established to distribute a more equitable gender division of la-bour. By including men in the social reproduction process, men and women can share equally in the social reproduction activities. This is conducive to changing the traditional gender division of labour and norms, relieving women of their double burden and promoting gender equality in social reproduction.

Paternity leave dates back to the 1960s, when, in response to labour shortages, the Swedish government encouraged more and more women to participate in productive activities. Yet, women also carried the primary responsibility for child-rearing in this time, leading to a dual burden. This prompted the need for a change. As a result, the Swedish Government adopted the Parental Leave 1947 in 1974 [31]. Parental Leave 1947 allowed for parental leave to be shared between two parents, replacing maternity leave, which was taken solely by the mother. It means that mothers are not solely responsible for childcare in legal, but that fathers have the same parental responsibility as mothers. Thus, the inequality and imbalance between couples in terms of unpaid labour was changed. In practice, however, fathers’ leave rates were extremely low, never exceeding 10 per cent between 1974 and 1994, and mothers continued to dominate the household and childcare [32]. To increase fathers’ leave rates, the Swedish government amended the Parental Leave 1947 in 1995 to create a one-month non-transferable, use-it-or-lose-it paid parental leave for men. This month-long holiday, also known as fathers’ quotas, makes it clear that fathers are also one of the subjects of parenting [33-36]. At the same time, the Swedish Social Insurance Code specifies that fathers are entitled to a paternity allowance from the Government during the period of leave. If the father forgoes his leave or does not complete the month, the family loses the one-month paid allowance [31]. By 2016, paternity leave for fathers had increased from one month to three months [31]. This further encourages fathers to take a break from their jobs and effectively engage in parenting activities and responsibilities.

The significance of paternity leave in reducing women’s burden in social re-production has been widely discussed in academia. Historically, when a child was born in heterosexual couples, it often resulted in a gender-based division of labour [37,38]. New mothers assumed primary caregiver roles and learned parenting patterns in the months following birth, while fathers had limited time for involvement. This created a gendered division of labour, with mothers taking on most unpaid childcare responsibilities, and fathers assisting when needed [2,39-47]. Importantly, these established parenting patterns proved resistant to change over time. After the establishment of paternity leave, the establishment of paternity leave helps men to temporarily with-draw from the labour market and enhances their understanding and practice of child-rearing. Fathers continually gain the skills and confidence to master parent-ing as they learn to parent [48]. In other words, paternity leave provides fathers with the space they need to develop their parenting skills and sense of responsibility, thus enabling them to become the main actors in parenting activities rather than their wives’ helpers [48-51]. Data show that taking paternity leave is positively correlated with subsequent father involvement. Research in Europe suggests that fathers who take longer periods of leave are more frequently in-volved in childcare tasks than fathers who take shorter periods of leave [52,53]; Evidence from the United States suggests that taking paternity leave, especially longer paternity leave, is associated with higher levels of father involvement [54-56]. Fathers are more likely to perceive themselves as having an important, or even necessary, role in their children’s lives and create an opportunity to develop a more equitable gender division of labour [48,57-59].

Paternity leave extends beyond merely enhancing men’s parenting skills; it fosters a deeper understanding. Men who experience paternity leave gain empathy for women’s roles and burdens in social reproduction, which encourages a willingness to share childcare responsibilities. Qualitative research by Petts and Knoester indicates that greater involvement in childcare helps men appreciate the importance of infant care and understand the challenges of motherhood, shed-ding light on previously overlooked aspects [60]. This heightened awareness underscores women’s contributions and motivated men to participate in childcare tasks [48,54, 60]. This transformation breaks down traditional gendered divisions of labour, enabling equal co-parenting rather than one partner shouldering all childcare and household duties. Consequently, paternity leave not only high-lights the value of women’s contributions to social reproduction but also blurs gender boundaries in this sphere, dismantling gender-based labour divisions. Unpaid childcare and domestic work are now shared between parents, alleviating the double burden on women. Ultimately, improving paternity leave provisions for men will advance gender equality, emphasize the importance of social repro-duction in society, and promote a more equitable social system.

3.Chinese Context

3.1.Social Background

Under the influence of Confucianism, the traditional concept of ‘men earning a living and women taking care of the family’ has existed in Chinese families for a long time. The traditional notion that women’s centre of gravity should be in the home led some women to believe that domestic work was their ‘natural duty’ [61]. During the period of the planned economy, China pursued a policy of high employment and placement, guaranteeing that urban women would have a job right after graduation [5]. In this case, women are also gradually entering the ranks of breadwinners, and the two-earner family has become the most basic organisational unit in towns and cities [62]. Under the planned economy, the State socialised domestic work and undertook the public function of childcare and old-age care on a collective and unitary basis, for example, by building nurseries and kindergartens of a welfare nature [2013]. Therefore, in China’s planned economy, women had high workforce participation without a significant double burden. The shift to a market economy dismantled the unitary system, replacing collective parenthood with individual responsibility. Now, each family manages social reproduction like child-rearing, resulting in heightened stress as most women contend with work-family conflicts [63].

Moreover, it is worth noting that, although women began to enter the field of production, they were more likely to be in a lower-paid secondary labour position relative to men due to China’s `low-wage, high-employment’ policy under the planned economy [5]. After the reform of the market economy, women, who were already in a secondary labour position, lost the security provided by the state and became the primary unemployed, resulting in a further decline in the economic status of women [5]. Thus, since men earn more than women, men’s contribution to the household is perceived to be greater and the status of the household is higher. Under these circumstances, women are more likely to sacrifice their own interests in decision-making to protect their husbands’ careers, thus further rein-forcing women’s subordinate status in society and in the family [62]. Data from the 2010 survey on the social status of women in China, conducted by the All-China Women’s Federation and the National Bureau of Statistics, show that in urban dual-income families, 17 per cent of women interrupted their work because of childbirth [64]. In terms of ‘who mainly takes care of the child until the child is three years old’, the proportion of those who are mainly taken care of by their husbands is 4.47 per cent, while the proportion of those whose wives are responsible for their care is 38.89 per cent. This shows that whether more women participate in the labour market, women are always at an economic disadvantage and their value in unpaid work is always perceived to be lower than men’s earnings in paid work. Their self-interest is therefore more likely to be sacrificed than that of men. Therefore, true gender equality cannot be achieved by simply integrating women into the productive sphere and giving them more economic opportunities. On the contrary, it is only by recognising women’s contribution to social repro-duction and breaking gendered division of labour that it is possible to change women’s subordinate positions.

3.2.Data Facts: Chinese Unequal Distribution of Domestic Labour

With more and more women entering the productive sphere, China has become one of the countries with the highest proportion of women participating in the labour force, and World Bank statistics for 2022 show that the labour force participation rate of women over 15 years of age in China has reached 61 per cent [65]. Despite the high rate of female employment and the growing popularity of the concept of gender equality in China, women’s inequality in social repro-duction is still evident, with domestic labour remaining the main task of women. As a result, women of all ages in Chinese households are often subjected to a double squeeze from both productive and reproductive labour.

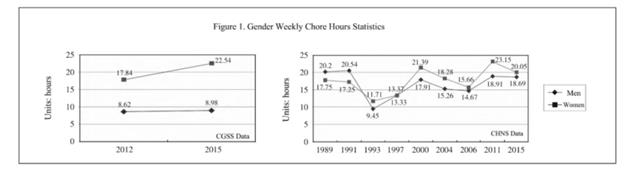

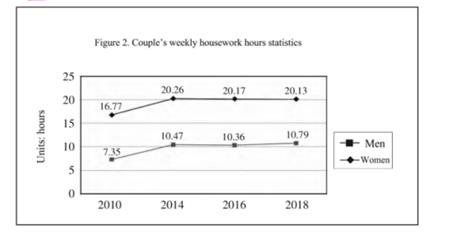

Figure 1 shows data from the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) and the Chinese Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS), respectively, which document the difference in the amount of time spent by men and women on unpaid domestic work. From the CGSS data for 2012 and 2015, women’s time spent on housework is much greater than men’s, and that the gap continues to grow, from twice as much as in 2012 to 2.5 times as much as in 2015; the same conclusion can be drawn from the CHNS data from 1993 onwards. Similarly, data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) show that among married couples living together, men spend half as much time on housework as women (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Gender weekly chore hours statistic. [66]

Figure 2: Couple’s weekly housework hours statistics. [66]

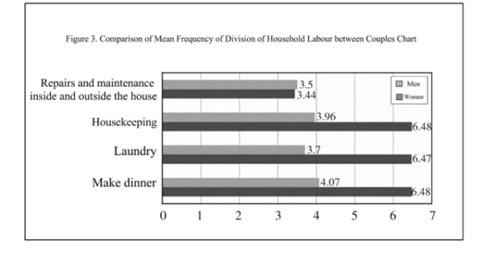

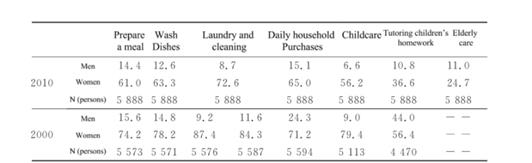

Figures 3 and 4 illustrate the gender disparity in terms of frequency and time spent on various unpaid domestic tasks. In 2017, CGSS data revealed that women performed tasks such as cooking dinner, laundry, and house cleaning nearly twice as often as men. Men were only slightly more involved in repairing and maintaining the house. These figures highlight the ongoing inequality in house-hold responsibilities. Figure 4 displays self-reported data on the division of household work among married individuals. While the proportion of domestic work performed by women decreased to some extent in 2010 compared to the 2000 survey, men’s involvement increased to varying degrees. Nevertheless, women still shouldered the majority of household chores. In 2010, women were responsible for 61% of cooking, 63.3% of dishwashing, 72% of laundry and sani-tation, 65% of daily household purchases, 56.2% of childcare, 36.6% of tutoring, and 24.7% of elderly care. This indicates that, despite men gradually entering the realm of social reproduction, a gender-based division of labour persists, with women primarily handling social reproduction tasks. The transition toward equal sharing of domestic responsibilities between spouses has not been fully realized.

Figure 3: Comparison of mean frequency of division of household labour between couples. [66]

Figure 4: Married people’s self-reported share of various types of household. [67]

To summarize, under the influence of the traditional concept of ‘men earn money, women take care of the family’, though more and more women in China are getting paid jobs, they still undertake a large amount of unpaid work. In terms of the total amount of housework, women’s tasks are much higher and more frequent than men’s; in terms of the time spent on housework, most of the data results show that women’s weekly time spent on housework is about twice as long as men’s time spent on housework, and this difference has not tended to diminish significantly over time. Thus, inequality between men and women in social re-production is still very evident in China.

4.Methodology Conclusion

4.1.Literature Research Method

Literature research method refers to the systematic and critical assessment of the collected literature by reviewing a large number of relevant laws and regulations, related books, academic journal articles, legislative documents, statistical data, and survey reports [68]. This method helps the researcher to conduct a comprehensive review of the background and theoretical foundations related to paternity leave in Sweden and China. In addition, the richness and credibility of the analysis is enhanced by identifying objective and actual data from different primary sources. This will help to summarize the key contents, advantages and implementation effects of paternity leave in Sweden and China.

4.2.Comparative Policy Analysis

Comparative policy analysis refers to the comparison of strengths and weak-nesses of policies across countries in terms of implementation outcomes, effectiveness and impacts, and then analysing the possibilities and challenges of transferring, or adapting a policy from one setting to another and make recommendations for policy improvement [69-71]. Sweden’s paternity leave legislation has an early origin, a well-developed system and a good implementation effect. By taking Sweden as a template, the specific contents of Sweden’s paternity leave system are sorted out and compared with China’s paternity leave provisions in different aspects. On this basis, the dissertation analyses the shortcomings of China’s legislation at this stage, and learns from Sweden’s policy while combining with China’s national conditions to provide certain reference and design ideas for improving China’s paternity leave system.

5.Policy Analysis

5.1.Sweden

Sweden has been focusing on the legislative exploration of paternity leave since 1970s and has now formed a comprehensive legal system of paternity leave. The Swedish Parental Leave Act establishes men as the subject of paternity leave, the number of days of paternity leave and the manner in which it is to be taken, as well as the protection of leave allowances. Therefore, this chapter takes Sweden as a sample, analyses the advantages of Swedish paternity leave, and provides a model for the improvement of China’s paternity leave legal system.

5.1.1.Father’s Quota Legislated at National Level

First, paternity leave is legislated for at a high level in Sweden and has a nationally unified legal system for paternity leave. Sweden establishes and protects the father’s non-transferable paternity leave nationally. The Swedish Parental Leave Act provides for 16 months of paid leave for each child until the child reaches the age of 12, irrespective of whether the parents are biological or married, in a quota to be arranged by the couple. However, the father is entitled to a fixed, non-transferable leave of three months. If the father abandons or does not take the full three months’ leave, he will not be able to receive the financial bene-fits provided by the social insurance system. Being protected by national law, employers cannot fire their employees during their leave and have no right to prohibit them from enjoying the benefits of paid leave [72]. If an employer violates the law and fails to give a permissive man the leave and salary he is entitled to, he should bear the legal consequences and be subject to legal sanctions [73]. This shows that the Swedish paternity leave system elevates the natural right of men to participate in childcare to a legal right, providing a legal basis and protection at the national level. In addition, the Parental Leave Act explicitly states that the subject of the right to paternity leave is a man. The Swedish paternity leave system transforms men’s natural right to engage in childcare into a legal entitlement, providing national-level legal foundation and protection. The Parental Leave Act explicitly designates men as the subjects entitled to paternity leave, emphasizing their indispensable role in reproductive childcare. This shift under-scores that reproductive responsibilities are not exclusive to women but extend to men as well, compelling their active involvement in social reproduction and challenging the stereotypical feminization of this sphere. Consequently, fathers cease being mere assistants to mothers, and both spouses share family responsibilities. This liberation from domestic labour enables women to escape economic disadvantages and break free from male subordination.

With strong policy interventions in Sweden, Swedish socio-cultural attitudes have also changed. Whereas fathers were initially sarcastically labelled as ‘velvet daddies’ when they took parental leave, nowadays a stay-at-home dad is no longer something to be ashamed of, and society no longer sees work as the only measure of a successful man [74]. This is due to the fact that the idea of couples sharing social reproductive activities has been internalised in Swedish law, and as a result, society has grown to agree on the shared responsibility of childcare. Data show that the introduction of paternity leave has led to a rapid increase in the rate of fathers taking leave in Sweden from less than 10 per cent to 82 per cent [31]. By 2020, almost 90 per cent of Swedish fathers will choose to take paid paternity leave [75]. In addition, Sweden not only has one of the highest rates of fathers taking parental leave in the world, but the women’s employment and fertility rates are also consistently high all year round [76]. Swedish data show that when fathers take parental leave, women’s monthly earnings increase by 7 per cent [77]. The employment rate of mothers aged 15-64 in Sweden is 77.5 per cent, much higher than the OECD average [78]. The Swedish paternity leave system fosters work-life balance for women, reducing their economic dependence on men. This, in turn, sustains high fertility rates and employment levels while promoting the sustainability of both the social reproduction and production sec-tors. Sweden’s paternity leave system institutionalizes shared responsibility be-tween genders in social reproduction within its legal framework. It is nationally mandated, with uniform guidelines making paternity leave a fundamental legal right and obligation for men. Men are compelled to actively engage in childcare and share social reproduction responsibilities with women. This not only acknowledges the value of social reproduction but also alleviates women’s dual burdens, contributing significantly to women’s emancipation.

5.1.2.Length and Flexibility of Paternity Leave

According to the Parental Leave Act, which was amended in 2016, parents share 480 days of parental leave, with three months of exclusive non-transferable leave for fathers, and the remainder of the time can be used flexibly by both parents [79]. Research has shown that paternity leave of more than three weeks will not only help fathers develop their parenting skills but increase their confidence in parenthood [49,80]. It also challenges perceptions of the traditional gender division of labour in social reproduction and increases the frequency with which fathers continue to be involved in the care of their children in later life. Conversely, shorter leave periods are not only insufficient to improve fathers’ parenting skills and sense of responsibility but also mean that fathers are less involved in parenting tasks later in life, and the burden on mothers is greater [48,51,54,81]. It has been shown that in Sweden, as the number of days of leave increases, so does the frequency of Swedish fathers’ involvement in accompanying their children, caring for them and physical care at a later date [52]. Therefore, the three-month paternity leave exclusively for men in Sweden can effectively include men in social reproduction to alleviate the double burden on women.

Secondly, Swedish paternity leave is very flexible. Sweden has adopted a system of split leave and Semi-leave. Split leave means that the main body of the leave can choose to flexibly arrange the time of leave between 60 days before the expected date of birth and the child’s 12th birthday, without having to finish the whole course at once. Semi-leave means that the father can adopt a pattern of combining work and rest in one day. The amount of leave can be a full day’s leave, a half day’s leave, a quarter day’s leave, and an eighth day’s leave (1 hour) [82]. In addition, Swedish legislation allows fathers to exchange more days of leave for a lower rate of leave allowance [31]. This flexible arrangement system allows for a high degree of freedom and adjustability in the implementation of paternity leave. Fathers can take advantage of this flexibility to take care for their children. Women are also better able to balance their lives and work, easing the double burden. Overall, each family can organise the use of leave according to their own circumstances, which prevents it from being wasted or lacking. It con-tributes to men’s genuine participation in social reproduction and to gender equality in social reproduction.

5.1.3.Subjects of the Cost Burden

Swedish legislation specifies that paternity leave benefits are to be supported by the national public purse and that the benefits are to be paid entirely from the Swedish social insurance system. The government supports the allowances, bene-fits, bonuses, etc. paid for paternity leave from Swedish public finance taxes. The amount of the paternity allowance is linked to the father’s income level prior to the leave and is 85 per cent of the father’s salary prior to the leave, with a guaranteed minimum of SEK 180 per day [83]. The burden of paternity benefits is mainly borne by the government, with employers accounting for a small proportion and the individual worker bearing virtually no cost [83]. As a result, Sweden has developed a socialised pay compensation mechanism for paternity leave income. Research has shown that if higher levels of replacement pay during leave are borne entirely by the employer, this can lead to high costs for the employer, leading to negative attitudes towards paternity leave and thus creating artificial barriers to workers applying for leave [78]. This Swedish burden model effectively reduces the likelihood of employers denying employees leave in their own financial interests. This means that the implementation of paternity leave is effectively improved, allowing couples to share childcare tasks more equally. Furthermore, from an employee’s perspective, paid paternity leave means that men can take leave without significantly sacrificing their pay packages. Research has shown that if fathers are not provided with some form of alternative pay for taking pa-rental leave to protect the financial security of the person taking the leave, this can be a huge disincentive for fathers to take parental leave. For example, parental leave in Spain is unpaid, leaving less than 1 per cent of fathers to use the right; in Sweden, for example, more than 90 per cent of fathers exercise their right to parental leave, as the wage replacement rate in Sweden is more than 80 per cent [74]. This suggests that the Swedish cost-burden distribution model could substantially increase the rate at which men take paternity leave. Therefore, this rea-sonable cost-burden model in Sweden is conducive to paternity leave being truly effective and increasing male participation in social reproduction. It also further breaks the traditional gender division of labour in social reproduction and effectively relieves women’s double burden.

In general, Sweden has a well-developed system of paternity leave. This includes a national law guaranteeing a quota of leave for fathers, sufficient leave hours and flexible leave options that allow fathers to participate effectively in parenting activities, and the Government’s primary responsibility for the cost of paternity leave benefits, which greatly increases the rate of paternity leave taken.

5.2.China

Compared to Sweden’s comprehensive paternity leave system, the legalization of paternity leave in China is still in the exploratory phase, lagging behind and fragmented. Paternity leave in China has emerged as an ‘incentive leave’ to regulate population rather than as a means to promote gender equality in social re-production [31]. As China’s society develops and the quality of its population improves, the population is now at a stage of long-term low growth; coupled with the fact that women face the double pressure of work and life, Chinese women of childbearing age have little desire to have children, and thus China is facing the social problem of an ageing population and an ageing workforce [31]. In this con-text, paternity leave, as one of the state’s means of encouraging childbearing, serves the macro-strategy of population regulation [84]. Therefore, based on the analysis of Sweden’s paternity leave system, this chapter looks back at the cur-rent situation of China’s paternity system and puts forward proposals to supplement and improve China’s paternity leave legal system. However, at the same time, in view of the different development modes of Swedish and Chinese societies, the reference to Sweden’s advanced legislative experience is also combined with China’s national conditions to enhance the operability of the recommendations.

5.2.1.Raising the Level of Legislation and Establishing a Father’s Quota

Compared to Sweden, where paternity leave legislation is of a high order and men have exclusive leave quotas, China’s paternity leave system is of a low legal order, with insufficient authority, and men-only leave is not mandatory. China’s existing law on maternity protection is the Population and family planning law of the peoples Republic of China, but the maternity leave is mainly for women, and the law has not yet explicitly regulated the content of paternity leave for men [78]. Paternity leave for men is generally reflected in local Family Planning Regulations. At present, there are 34 provincial-level administrative units in China, and all 30 of them, with the exception of the Tibet Autonomous Region, have simple provisions for paternity leave for men in their family planning regulations [31]. However, local laws do not mandate paternity leave or specify it as an inherent right for men. Thus, men’s entitlement to paternity leave is primarily moral rather than legal. This leads to inadequate employer focus and many men not recognizing their role in childcare and societal reproduction. This lack of aware-ness perpetuates the double burden on women and the importance of paternity leave. Research conducted by the Beijing Municipal Federation of Trade Unions shows that out of the male workers surveyed, 41.78 per cent had not utilized paternity leave, and 39 per cent were unsure whether their workplaces offered such leave; Around 64.53 per cent of the male workers knew paternity leave but opted not to take it due to concerns about work interference; Many male workers ex-pressed apprehension about taking paternity leave and, instead, decided to spend time with their wives and babies using other forms of leave, such as annual leave, casual leave, or working overtime [85]. This suggests that under the positioning of paternity leave as ‘incentive leave’, the local regulations lack gender-specific and mandatory requirements for male workers to take on family responsibilities and participate in social reproduction activities, which makes it difficult to reflect the pursuit of paternity leave for gender equality in social reproduction. Therefore, it is unrealistic to rely solely on the self-driven efforts of provinces and cities to promote the development of paternity leave, and the country needs to establish national legislation to explicitly promote the implementation of paternity leave.

In view of this, a broader national approach through legislative means emerges as a necessity to systematically propel the implementation of paternity leave. Firstly, China needs to transform the positioning of the paternity leave system, removing its attribute of incentive leave for encouraging childbirth. The natural rights and obligations of men to participate in childcare activities are elevated to legal rights and obligations and the values of gender equality in social reproduction should be embedded in the legislation on paternity leave. Furthermore, the legislative status of paternity leave needs to be upgraded and provided with a national legal basis. Specifically, the paternity leave system for male workers can be separated from the family planning regulations of each region and written into the Labour Law of the People’s Republic of China (Labour Law). The Labour Law, as a national legislation, already contains a relatively complete system of maternity leave protection, and the institutional construction and operational mechanism of paternity leave and maternity leave are figured out, thus providing a good judicial basis [86]. Therefore, both maternity and paternity leave can be incorporated into the Labour Law. Article 62 of the Labour Law can be amended as follows: ‘Female employees are entitled to a minimum of ninety days of maternity leave for childbirth, and their spouses are entitled to a minimum of 30 days of paternity leave.’ Including paternity leave in a unified national law enhances its enforceability and signifies the role of national legislation in shaping societal attitudes. This encourages employers to respect this right and discourages them from arbitrarily denying men paternity leave. It also raises societal awareness about men’s participation in social reproduction activities, ultimately increasing the uptake of paternity leave and enabling men to fulfil their family responsibilities. Moreover, the exclusive leave quota for men internalizes the concept of breaking down gender divisions in social reproduction within the le-gal framework, promoting gender equality in this sphere through legal means.

5.2.2.Increasing the Length and Flexibility of Paternity Leave

Compared to Sweden, where male workers are entitled to three months’ paternity leave and flexible leave options, paternity leave in China is shorter and more rigid. The number of days of paternity leave varies considerably across China’s provinces, with leave lengths ranging from 7 to 30 days, such as 7 days in Shan-dong, 15 days in Beijing and 30 days in Yunnan [87]. In addition, paternity leave in China is not flexible. Men are usually required to take paternity leave in one go, and the leave is not postponed for rest days or legal holidays [72]. This rigid leave model fails to fully respect the need for flexibility in balancing family responsibilities and work, thus defeating the original purpose of paternity leave and limiting its effectiveness. Due to the lack of flexible leave patterns, men can-not give practical help in childcare activities, after which most of the childcare responsibilities fall on women. It is therefore recommended that the duration of paternity leave be extended and that a flexible leave pattern be established.

As mentioned earlier, the three-month paternity leave in Sweden has helped to effectively enhance and develop men’s parenting skills and sense of responsibility. Moreover, studies have also shown that paternity leave of more than three weeks not only effectively increases the frequency of fathers’ participation in social reproduction activities in the future, but also challenges stereotypes about the traditional gender division of labour in this area [48,81,88]. By analogy with China, paternity leave of less than three weeks would have little effect on reducing the double burden on Chinese women, increasing the fertility intentions of families of childbearing age, and addressing the status quo of an ageing population. However, the number of days of paternity leave should not be too long in light of China’s national conditions. This is because there is still a gap between China and high welfare countries like Sweden, and because the population base is so large that the state’s financial resources are insufficient to support a long period of childcare leave benefits. In addition, in China, where there is a large labour shortage, an excessively long leave will increase the burden on enterprises and make it more difficult to implement paternity leave. Therefore, on balance, 30 days is most appropriate. A one-month leave not only enables men to better participate in future social reproduction activities, but also makes the paternity leave system more practical and quicker to implement. In terms of leave flexibility, Sweden’s institutional arrangement provides a reference for China’s paternity leave. China’s paternity leave system can learn from Sweden’s and introduce a flexible leave time system. Paternity leave can be granted in units of days or one-half of a day, and the leave can be dispensed in phases according to the actual needs of the leave recipient. Specifically, it is possible to add after article 62 of the Labour Law that ‘men entitled to paternity leave may arrange the number of days of leave according to the actual situation of the leave body, and it is not necessary to take consecutive days of leave, and it can be applied both before and after childbirth.’ At the same time, male employees should notify their employers about their paternity leave plans within a designated time frame, allowing for better work task coordination. Adequate leave days and flexible options enhance the effectiveness of the paternity leave system in easing the burden on women in social reproduction. This is vital for increasing male workers’ utilization of paternity leave and ensuring its practical implementation.

5.2.3.Establishment of a Reasonable Cost-burden Model

In Sweden, state support for paternity leave is high. As mentioned earlier, during the leave period for male workers, the Swedish government bears the main cost of the leave, and enterprises mainly play the role of executors, so that workers’ salaries are basically not affected too much. In contrast, in China, although the paternity leave system stipulates that men’s wages and treatment remain un-changed during the leave period, the cost of the leave is mainly guaranteed by the employer, and no corresponding socialization mechanism has been established [78]. Except for individual places such as Jiangsu Province, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region and Wuhan City, which stipulate in their local government regulations that the wages and benefits of male workers during paternity leave should be shared by the enterprise and the government, the relevant legislation in other places generally places the responsibility for granting allowances and benefits during paternity leave on the employer alone [87]. ‘The government treats, but enterprises foot the bill,’ creating significant financial strain on small and medium-sized businesses. They must cover the employee’s salary during leave and additional costs from job vacancies, leading them to reject the system due to financial constraints. The implementation of paternity leave depends very much on the size of the enterprise and the ‘conscience’ of the employer [31]. Therefore, the serious lack of government responsibility has made it difficult to put paternity leave into practice in reality. However, it is not quite realistic to directly copy the Swedish model where the government is fully responsible. This is because China’s population base is large and its economy is still in the development stage, so the government’s financial resources are not yet able to cover the full cost of the benefits. In this regard, it is necessary for China to clarify in the social insurance law that working men can obtain the benefits of paternity leave allowance from the social insurance fund. Through a mechanism for sharing the cost of paternity leave, the pressure on employers to cover the cost of labour will be spread out, and the resistance to the implementation of the system will be overcome.

In China today, it is the Maternity Insurance that is directly related to maternity leave entitlements. With the integration of maternity insurance into the medical insurance reform, the previous maternity insurance benefits are now centrally collected and paid for by the social medical insurance fund. However, the Social Insurance Law of the People’s Republic of China only protects the maternity interests of female workers. Therefore, it is possible to add the cost of leave for paternity leave in social medical insurance. Male workers are established in the Social Insurance Law as the subject of rights in the maternity protection system, and the cost of their leave benefits is unified and coordinated by social insurance. As far as system design is concerned, the item ‘male employees enjoying paternity leave’ can be added to Article 56 of the Social Insurance Law, ‘Employees enjoying maternity allowance’. It can be stipulated that ‘Paternity leave allowance for working men, granting male workers the right to receive financial support from social insurance during the leave period’. This proposal has a certain degree of feasibility. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China’s National Economic and Social Development Statistics Bulletin, China’s Maternity Insurance Fund has been in a situation where its income exceeded its expenditure, and the amount of its balance has been on an upward trend from 2010-2015 [89]. After the integration of maternity insurance into the medical insurance reform, the medical insurance fund (including maternity insurance) also has an adequate balance of 3.14 trillion yuan in 2021 [90]. On this basis, the Chinese government can make reasonable use of the unused fund to extend social insurance coverage to paternity leave for male workers and form a socialised security system, which changes the situation in which the employer directly bears the paternity leave allowance. This would alleviate the financial burden on employers to a greater extent and increase their willingness to support paternity leave for male workers, thus making paternity leave a real reality on the ground. Therefore, China should consider its own level of economic development and establish a cost-sharing mechanism that matches it. Only when the cost of paternity leave is shared by society can one of the major obstacles to men’s entry into the field of social reproduction be removed, and an important step towards gender equality in the field of social reproduction be taken.

To sum up, China should learn from the successful experience of Sweden and at the same time improve its paternity leave system in the light of its own actual situation. This includes clarifying the father’s quota and upgrading the legislative status of paternity leave, stipulating the length of paternity leave to be about one month, and supplementing it with a flexible leave system, and adopting a model in which paternity leave allowances are shared among individuals, enterprises and the State. Through the continuous improvement of the paternity leave system, men will be included in social reproduction and a model of shared responsibility between the sexes will be promoted.

6.Conclusion

To summarize, despite China as one of the countries with the highest female employment rate, women’s educational and economic levels have increased significantly. However, in social reproduction, women still bear the lion’s share of unpaid domestic work, including childcare, and their contribution in this regard has long been overlooked. This has significantly increased women’s double bur-den of work and life, which is detrimental to women’s personal well-being and the sustainability of society. To alleviate women’s double burden, break down the gender division of labor and promote gender equality in the field of social repro-duction, the introduction of a paternity leave system is of great significance. Sweden has embedded the concept of gender equality well in its paternity leave system and utilized the law to include men in social reproduction, transforming the social stereotype of the traditional gender division of labor. Under the Swe-dish paternity system, a very high percentage of Swedish fathers take paternity leave, and men actively participate in childcare activities, sharing the pressure of women in the field of social reproduction. This not only promotes gender-equal division of family responsibilities, but also guarantees long-term stable population growth and sustainable social development. In contrast, China’s paternity leave, under the positioning of incentive leave, faces a series of problems such as low legislative status, lagging legislative concepts, short leave hours, rigid leave methods, and unreasonable cost-burden patterns. This greatly inhibits the paternity leave system landing and effect. Therefore, China should take Sweden’s paternity leave system as a model, learn from its excellent legislative experience, and combine it with China’s national conditions to improve its own paternity leave system. Only in this way can the paternity leave system reflect the value of gender equality in the field of social reproduction and better contribute to the sustainable development of society.

References

[1]. Hochschild, A., & Machung, A. (2012). The second shift: Working families and the revolution at home. Penguin.

[2]. Bianchi, S. M., Milkie, M. A., Sayer, L. C., & Robinson, J. P. (2000). Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in the gender division of household labor. Social forces, 79(1), 191-228.

[3]. Killewald, A., & Gough, M. (2010). Money isn’t everything: Wives’ earnings and housework time. Social science research, 39(6), 987-1003.

[4]. Braunstein, E., Bouhia, R., & Seguino, S. (2020). Social reproduction, gender equality and economic growth. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 44(1), 129-156.

[5]. Tong, X.. (1999). Social change and the history and trend of women’s employment in China. Women’s Studies Series (01), 38-41.

[6]. Tong, X and Zhou, Lvjun (2013). Balance between employment and family caregiving:A comparison based on gender and occupational position[J]. Xuehai,2013(02):72-77.

[7]. Chen, L., Fan, H., & Chu, L. (2020). The Double-Burden Effect: Does the Combination of Informal Care and Work Cause Adverse Health Outcomes Among Females in China?. Journal of Aging and Health, 32(9), 1222-1232.

[8]. Rai, S. M., Hoskyns, C., & Thomas, D. (2014). Depletion: The cost of social reproduction. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 16(1), 86-105.

[9]. Bhattacharya, T. (2017). Introduction. Mapping Social Reproduction Theory [w:] Social Reproduction Theory. Remapping Class, Recentring Oppression, ed. T. Bhattacharya, foreword L. Vogel.

[10]. Arruzza, C. (2016). Functionalist, determinist, reductionist: Social reproduction feminism and its critics. Science & Society, 80(1), 9-30.

[11]. Beneria, L. (1999). The enduring debate over unpaid labour. Int’l Lab. Rev., 138, 287.

[12]. Ferguson, S. (2016). Intersectionality and social-reproduction feminisms: Toward an integrative ontology. Historical Materialism, 24(2), 38-60.

[13]. Fraser, N. (2017). Feminism, capitalism and the cunning of history. In Citizenship rights (pp. 393-413). Routledge.

[14]. Munro, K. (2019). “Social reproduction theory,” social reproduction, and household production. Science & Society, 83(4), 451-468.

[15]. Hoskyns, C., & Rai, S. M. (2007). Recasting the global political economy: Counting women’s unpaid work. New political economy, 12(3), 297-317.

[16]. Laslett, B., & Brenner, J. (1989). Gender and social reproduction: Historical perspectives. Annual review of sociology, 15(1), 381-404.

[17]. Brenner, Johanna. (2000). Women and the Politics of Class. New York: Monthly Review.

[18]. Benería, L., Berik, G., & Floro, M. (2015). Gender, development and globalization: Economics as if all people mattered. Routledge.

[19]. Lamphere, L. (1987). From Working Daughters to Working Mothers. Ithaca, NY: Cor- nell Univ. Press.

[20]. Luxton, M. (1980). More than a labour of love: Three generations of women’s work in the home (Vol. 2). Canadian Scholars’ Press.

[21]. Luxton, M. (2006). Feminist political economy in Canada and the politics of social reproduction. Social reproduction: Feminist political economy challenges neo-liberalism, 11-4.

[22]. Smith, D. (1987). Women’s inequality and the family. See Gerstel & Gross 1987, pp. 23- 54.

[23]. Armstrong, J., Walby, S., and Strid, S. (2009). The gendered division of labour: how can we assess the quality of employment and care policy from a gender equality perspective?. Benefits: A Journal of Poverty and Social Justice, 17(3), 263-275.

[24]. Federici, Silvia (2014). Caliban and the Witch : Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. 2nd rev. ed. Brooklyn, NY: Autonomedia, 2014. Print.

[25]. Dalla Costa, Mariarosa., and Selma James (1975). The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community. 3rd ed. Bristol: Falling Wall Press Ltd. Print.

[26]. Federici, S. (1975). Wages against housework (pp. 187-194). Bristol: Falling Wall Press.

[27]. Vogel, L. (2013). Marxism and the oppression of women: Toward a unitary theory. Brill.

[28]. Charmes, J. (2006). A review of empirical evidence on time use in Africa from UN-sponsored surveys, in Blackden, C. M. and Wodon, Q. (eds), Gender, Time Use, and Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa, World Bank Working Paper No. 73.

[29]. Budlender, D. (2008). ‘The Statistical Evidence on Care and Non-Care Work across Six Countries’, Gender and Development Programme Paper No. 4, UNRISD.

[30]. Kabeer, N. (2016). Gender equality, economic growth, and women’s agency: the “endless variety” and “monotonous similarity” of patriarchal constraints. Feminist Economics, 22(1), 295-321.

[31]. Zhao, Xiaobai (2022). Research on the legal system of paternity leave in China [D]. Lanzhou University.

[32]. Johansson, T. (2011). Fatherhood in transition: Paternity leave and changing masculinities. Journal of family communication, 11(3), 165-180.

[33]. Ellingsæter, Anne Lise and Leira, Arnlaug (2006). Introduction in Ellingsæter, AL; Leira A, eds. Politicising parenthood in Scandinavia. Gender relations in welfare states. Bristol: Policy Press, 1–18.

[34]. Eydal, Guðny Bjork (2005). Childcare policies of the Nordic welfare states: different paths to enable parents to earn and care? In: Pfau-Effinger, Birgit; Geissler, Birgit, eds. Care and social integration in European societies. Bristol: Policy Press: 153–173.

[35]. Haataja, A. (2009). Fathers’ use of paternity and parental leave in the Nordic countries.

[36]. Rostgaard, Tine (2002). Setting time aside for the father: father’s leave in Scandinavia. Community, Work and Family. 5 (3): 343–364.

[37]. Cowan Carolyn, and Philip Cowan. (1992). When partners become parents: The big life change for couples. New York: Basic Books.

[38]. Walzer, S. (1998). Thinking about the baby: Gender and transitions into parenthood (Vol. 105). Temple University Press.

[39]. Bobel, Chris. (2002). The paradox of natural mothering. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

[40]. Chodorow, Nancy. (1978). The reproduction of mothering: Psychoanalysis and the sociology of gender. Berkeley: University of California Press.

[41]. Miller, Tina. (2007). Is this what motherhood is all about? Weaving experiences and discourse through transition to first-time motherhood. Gender & Society 21:337-58.

[42]. Oakley, Ann. (1979). Becoming a mother. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

[43]. Allen, Sarah, and Alan Hawkins. (1999). Maternal gatekeeping: Mothers’ beliefs and behaviors that inhibit greater father involvement in family work. Journal of Marriage and Family 61:199-212.

[44]. Craig, Lyn, and Killian Mullan. (2011). How mothers and fathers share childcare: A cross-national time use comparison. American Sociological Review 76:834-61.

[45]. Coltrane, Scott. (1996). Family man: Fatherhood, housework, and gender equity. New York: Oxford University.

[46]. Ehrensaft, Diane. (1987). Parenting together: Men and women sharing the care of their children. New York: Free Press.

[47]. Gerson, Kathleen. (1993). No man’s land: Men’s changing commitment to family and work. New York: Basic Books.

[48]. Rehel, E. M. (2014). When dad stays home too: Pater- nity leave, gender, and parenting. Gender & Society, 28, 110–132.

[49]. Cabrera, N. J., Fagan, J., & Farrie, D. (2008). Explaining the long reach of fathers’ prenatal involvement on later paternal engagement. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 1094–1107.

[50]. Marsiglio, W., & Roy, K. (2012). Nurturing dads: Social initiatives for contemporary fatherhood. New York: Russell Sage.

[51]. Roggman, L. A., Boyce, L. K., Cook, G. A., & Cook, J. (2002). Getting dads involved: Predictors of father involvement in Early Head Start and with their children. Infant Mental Health Journal, 23, 62–78.

[52]. Haas, L., & Hwang, C. P. (2008). The impact of taking parental leave on fathers’ participation in childcare and relationships with children: Lessons from Sweden. Community, Work, and Fam- ily, 11, 85–104.

[53]. Huerta, M. C., Adema, W., Baxter, J., Han, W., Lausten, M., Lee, R., & Waldfo- gel, J. (2014). Fathers’ leave and fathers’ involvement: Evidence from four OECD countries. European Journal of Social Secu- rity, 16, 308–346.

[54]. Pragg, B., & Knoester, C. (2017). Parental leave usage among disadvantaged fathers. Journal of Family Issues, 38, 1157–1185.

[55]. Nepomnyaschy, L., & Waldfogel, J. (2007). Pater- nity leave and fathers’ involvement with their young children. Community, Work and Family, 10, 427–453.

[56]. Seward, R. R., Yeats, D. E., Amin, I., & DeWitt, A. (2006). Employment leave and fathers’ involvement with children. Men and Masculinities, 8, 405–427.

[57]. Pasley, K., Petren, R. E., & Fish, J. N. (2014). Use of identity theory to inform fathering scholarship. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 6, 298–318.

[58]. Rane, T. R., & McBride, B. A. (2000). Identity theory as a guide to understanding fathers’ involvement with their children. Journal of Family Issues, 21, 347–366.

[59]. Stryker, S. (1968). Identity salience and role per- formance: The relevance of symbolic interaction theory for family research. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 30, 558–564.

[60]. Petts, R. J., & Knoester, C. (2018). Paternity leave-taking and father engagement. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80(5), 1144-1162.

[61]. Tong, ShaoSu. (1994). Role Confusion and Women’s Way Out--A Review of the International Conference on “Contemporary Role Conflict Research of Working Women”. Zhejiang Journal (01).

[62]. Tong, X., Long, Y.. (2002). Reflection and Reconstruction--A Review of Research on Gender Division of Labor in China. Zhejiang Journal (04).

[63]. Shen Chonglin, Yang Shanhua, and Li Dong. (1999). Urban and Rural Families at the Turn of the Century. China Social Science Press. p91.

[64]. Third Survey on the Social Status of Chinese Women (2011). All-China Women’s Federation and National Bureau of Statistics. Available from: http://www.china.com.cn/zhibo/zhuanti/ch-xinwen/2011-10/21/content_23687810.htm (Accessed19 July 2023 ).

[65]. The world bank (2023). Labor force participation rate, female (% of female population ages 15+) (modeled ILO estimate). Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.FE.ZS (Accessed19 July 2023).

[66]. Yu, Zhilin (2022). Analysis of the current situation of division of labour in domestic work in China[J]. Co-operative Economy and Science and Technology,2022(23):84-87.

[67]. Liu Aiyu, Tong Xin, Fu Wei (2015). Gendered division of household chores in dual-income families:economic dependence, gender concepts, or emotional expression[J]. Society,2015,35(02):109-136.

[68]. Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: an overview and guidelines. journal of business research, 104, 333-339.

[69]. Breuning, M. (2007). Foreign policy analysis: A comparative introduction. Springer.

[70]. Hofferbert, R. I., & Cingranelli, D. L. (1996). Public policy and administration: comparative policy analysis. A new handbook of political science, 593-609.

[71]. Radin, B. A., & Weimer, D. L. (2020). Compared to what? The multiple meanings of comparative policy analysis. Theory and Methods in Comparative Policy Analysis Studies, 43-58.

[72]. Li Chunxiu. (2022). Research on the legal system of paternity leave. Liaoning University.

[73]. Liu, S. N.. (2020). On the Improvement of the Legal System of Paternity Leave in China. China University of Mining and Technology.

[74]. Hu, Yukun. (2019). From “Velvet Daddy” to “Latte Daddy”-Institutional and conceptual changes of paid paternity leave in Sweden. Social Science Forum (05), 183-191.

[75]. Diesel. (2010). Swedish legal system against employment discrimination. China Labour (03), 28-30.

[76]. Fertility rate, total (births per woman) - Sweden(2022). United Nations Population Division. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=SE (Accessed 19 July 2023).

[77]. Guo, J. (2017). What is the Best Paid Parental Leave Arrangement to Promote Gender-Balanced Caregiving in the Home, and Gender Equality in the Workplace in New Zealand. NZWLJ, 1, 65.

[78]. Wang, Jian. (2022). From ‘Gender Difference’ to ‘Gender Neutrality’ to ‘Gender Reinvention’: Extraterritorial Experience of Parental Leave Legislation and Its Implications. Global Law Review (05), 147-162.

[79]. Guo, W. H.. (2022). Research on the legal system of maternity leave. Liaoning University.

[80]. Lamb, Michael. (2004). The role of the father in child development, 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

[81]. Lamb, M. E. (2010). How do fathers influence children’s development? Let me count the ways. In M.E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development, 5th edition (1–26). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

[82]. Wells, M. B., & Bergnehr, D. (2014). Families and family policies in Sweden. Handbook of family policies across the globe, 91-107.

[83]. Your social security rights in Sweden (2022). European Commission. Available from: file:///Users/lily/Downloads/missoc-ssg-SE-2022-en.pdf (Accessed 19 July 2023).

[84]. Liang, JZ and Guo, ZG (2013). Fertility policy adjustment and China’s development [M]. Beijing:Social Science Literature Press,199-201.

[85]. How to reassure workers after the extension of maternity leave? (2022). Beijing Municipal Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. Available from: http://www.bjzx.gov.cn/ztzl/zxqh/zxh2022/mtgz202201/202201/t20220106_38357.html (Accessed 19 July 2023).

[86]. Qiu, Yumei and Tian, Mengmeng. (2014). Research on “paternity leave” system. Times Law (03), 63-72.

[87]. Pan, X. T.. (2021). Research on paternity leave system in China. Tianjin Normal University parenthood. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

[88]. Lamb, M. E., Chuang, S. C., & Hwang, C. P. (2004). Internal reliability, temporal stability, and correlates of individual differences in paternal involvement: A 15-year longitudinal study in Sweden. In R. D. Day & M. E. Lamb (Eds.), Conceptualizing and measuring father involvement (pp. 129–148). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

[89]. Ying, Jieqin. (2018). On the Establishment and Improvement of the Legal System of Parental Leave. East China University of Politics and Law.

[90]. Statistical Bulletin of the People’s Republic of China on National Economic and Social Development, 2021. (2022). National Bureau of Statistics of China. Available from: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-02/28/content_5676015.htm (Accessed 19 July 2023).

Cite this article

Li,P. (2023). Reflecting Social Reproduction in Chinese Policy: Learning from Sweden Successful Practices to Promote Gender Equality in Social Reproduction. Communications in Humanities Research,16,121-138.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Global Politics and Socio-Humanities

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Hochschild, A., & Machung, A. (2012). The second shift: Working families and the revolution at home. Penguin.

[2]. Bianchi, S. M., Milkie, M. A., Sayer, L. C., & Robinson, J. P. (2000). Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in the gender division of household labor. Social forces, 79(1), 191-228.

[3]. Killewald, A., & Gough, M. (2010). Money isn’t everything: Wives’ earnings and housework time. Social science research, 39(6), 987-1003.

[4]. Braunstein, E., Bouhia, R., & Seguino, S. (2020). Social reproduction, gender equality and economic growth. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 44(1), 129-156.

[5]. Tong, X.. (1999). Social change and the history and trend of women’s employment in China. Women’s Studies Series (01), 38-41.

[6]. Tong, X and Zhou, Lvjun (2013). Balance between employment and family caregiving:A comparison based on gender and occupational position[J]. Xuehai,2013(02):72-77.

[7]. Chen, L., Fan, H., & Chu, L. (2020). The Double-Burden Effect: Does the Combination of Informal Care and Work Cause Adverse Health Outcomes Among Females in China?. Journal of Aging and Health, 32(9), 1222-1232.

[8]. Rai, S. M., Hoskyns, C., & Thomas, D. (2014). Depletion: The cost of social reproduction. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 16(1), 86-105.

[9]. Bhattacharya, T. (2017). Introduction. Mapping Social Reproduction Theory [w:] Social Reproduction Theory. Remapping Class, Recentring Oppression, ed. T. Bhattacharya, foreword L. Vogel.

[10]. Arruzza, C. (2016). Functionalist, determinist, reductionist: Social reproduction feminism and its critics. Science & Society, 80(1), 9-30.

[11]. Beneria, L. (1999). The enduring debate over unpaid labour. Int’l Lab. Rev., 138, 287.

[12]. Ferguson, S. (2016). Intersectionality and social-reproduction feminisms: Toward an integrative ontology. Historical Materialism, 24(2), 38-60.

[13]. Fraser, N. (2017). Feminism, capitalism and the cunning of history. In Citizenship rights (pp. 393-413). Routledge.

[14]. Munro, K. (2019). “Social reproduction theory,” social reproduction, and household production. Science & Society, 83(4), 451-468.

[15]. Hoskyns, C., & Rai, S. M. (2007). Recasting the global political economy: Counting women’s unpaid work. New political economy, 12(3), 297-317.

[16]. Laslett, B., & Brenner, J. (1989). Gender and social reproduction: Historical perspectives. Annual review of sociology, 15(1), 381-404.

[17]. Brenner, Johanna. (2000). Women and the Politics of Class. New York: Monthly Review.

[18]. Benería, L., Berik, G., & Floro, M. (2015). Gender, development and globalization: Economics as if all people mattered. Routledge.

[19]. Lamphere, L. (1987). From Working Daughters to Working Mothers. Ithaca, NY: Cor- nell Univ. Press.

[20]. Luxton, M. (1980). More than a labour of love: Three generations of women’s work in the home (Vol. 2). Canadian Scholars’ Press.

[21]. Luxton, M. (2006). Feminist political economy in Canada and the politics of social reproduction. Social reproduction: Feminist political economy challenges neo-liberalism, 11-4.

[22]. Smith, D. (1987). Women’s inequality and the family. See Gerstel & Gross 1987, pp. 23- 54.

[23]. Armstrong, J., Walby, S., and Strid, S. (2009). The gendered division of labour: how can we assess the quality of employment and care policy from a gender equality perspective?. Benefits: A Journal of Poverty and Social Justice, 17(3), 263-275.

[24]. Federici, Silvia (2014). Caliban and the Witch : Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. 2nd rev. ed. Brooklyn, NY: Autonomedia, 2014. Print.

[25]. Dalla Costa, Mariarosa., and Selma James (1975). The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community. 3rd ed. Bristol: Falling Wall Press Ltd. Print.

[26]. Federici, S. (1975). Wages against housework (pp. 187-194). Bristol: Falling Wall Press.

[27]. Vogel, L. (2013). Marxism and the oppression of women: Toward a unitary theory. Brill.

[28]. Charmes, J. (2006). A review of empirical evidence on time use in Africa from UN-sponsored surveys, in Blackden, C. M. and Wodon, Q. (eds), Gender, Time Use, and Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa, World Bank Working Paper No. 73.

[29]. Budlender, D. (2008). ‘The Statistical Evidence on Care and Non-Care Work across Six Countries’, Gender and Development Programme Paper No. 4, UNRISD.

[30]. Kabeer, N. (2016). Gender equality, economic growth, and women’s agency: the “endless variety” and “monotonous similarity” of patriarchal constraints. Feminist Economics, 22(1), 295-321.

[31]. Zhao, Xiaobai (2022). Research on the legal system of paternity leave in China [D]. Lanzhou University.

[32]. Johansson, T. (2011). Fatherhood in transition: Paternity leave and changing masculinities. Journal of family communication, 11(3), 165-180.

[33]. Ellingsæter, Anne Lise and Leira, Arnlaug (2006). Introduction in Ellingsæter, AL; Leira A, eds. Politicising parenthood in Scandinavia. Gender relations in welfare states. Bristol: Policy Press, 1–18.

[34]. Eydal, Guðny Bjork (2005). Childcare policies of the Nordic welfare states: different paths to enable parents to earn and care? In: Pfau-Effinger, Birgit; Geissler, Birgit, eds. Care and social integration in European societies. Bristol: Policy Press: 153–173.

[35]. Haataja, A. (2009). Fathers’ use of paternity and parental leave in the Nordic countries.

[36]. Rostgaard, Tine (2002). Setting time aside for the father: father’s leave in Scandinavia. Community, Work and Family. 5 (3): 343–364.

[37]. Cowan Carolyn, and Philip Cowan. (1992). When partners become parents: The big life change for couples. New York: Basic Books.

[38]. Walzer, S. (1998). Thinking about the baby: Gender and transitions into parenthood (Vol. 105). Temple University Press.

[39]. Bobel, Chris. (2002). The paradox of natural mothering. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

[40]. Chodorow, Nancy. (1978). The reproduction of mothering: Psychoanalysis and the sociology of gender. Berkeley: University of California Press.

[41]. Miller, Tina. (2007). Is this what motherhood is all about? Weaving experiences and discourse through transition to first-time motherhood. Gender & Society 21:337-58.

[42]. Oakley, Ann. (1979). Becoming a mother. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

[43]. Allen, Sarah, and Alan Hawkins. (1999). Maternal gatekeeping: Mothers’ beliefs and behaviors that inhibit greater father involvement in family work. Journal of Marriage and Family 61:199-212.

[44]. Craig, Lyn, and Killian Mullan. (2011). How mothers and fathers share childcare: A cross-national time use comparison. American Sociological Review 76:834-61.

[45]. Coltrane, Scott. (1996). Family man: Fatherhood, housework, and gender equity. New York: Oxford University.

[46]. Ehrensaft, Diane. (1987). Parenting together: Men and women sharing the care of their children. New York: Free Press.

[47]. Gerson, Kathleen. (1993). No man’s land: Men’s changing commitment to family and work. New York: Basic Books.

[48]. Rehel, E. M. (2014). When dad stays home too: Pater- nity leave, gender, and parenting. Gender & Society, 28, 110–132.

[49]. Cabrera, N. J., Fagan, J., & Farrie, D. (2008). Explaining the long reach of fathers’ prenatal involvement on later paternal engagement. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 1094–1107.

[50]. Marsiglio, W., & Roy, K. (2012). Nurturing dads: Social initiatives for contemporary fatherhood. New York: Russell Sage.

[51]. Roggman, L. A., Boyce, L. K., Cook, G. A., & Cook, J. (2002). Getting dads involved: Predictors of father involvement in Early Head Start and with their children. Infant Mental Health Journal, 23, 62–78.

[52]. Haas, L., & Hwang, C. P. (2008). The impact of taking parental leave on fathers’ participation in childcare and relationships with children: Lessons from Sweden. Community, Work, and Fam- ily, 11, 85–104.

[53]. Huerta, M. C., Adema, W., Baxter, J., Han, W., Lausten, M., Lee, R., & Waldfo- gel, J. (2014). Fathers’ leave and fathers’ involvement: Evidence from four OECD countries. European Journal of Social Secu- rity, 16, 308–346.

[54]. Pragg, B., & Knoester, C. (2017). Parental leave usage among disadvantaged fathers. Journal of Family Issues, 38, 1157–1185.

[55]. Nepomnyaschy, L., & Waldfogel, J. (2007). Pater- nity leave and fathers’ involvement with their young children. Community, Work and Family, 10, 427–453.

[56]. Seward, R. R., Yeats, D. E., Amin, I., & DeWitt, A. (2006). Employment leave and fathers’ involvement with children. Men and Masculinities, 8, 405–427.

[57]. Pasley, K., Petren, R. E., & Fish, J. N. (2014). Use of identity theory to inform fathering scholarship. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 6, 298–318.

[58]. Rane, T. R., & McBride, B. A. (2000). Identity theory as a guide to understanding fathers’ involvement with their children. Journal of Family Issues, 21, 347–366.

[59]. Stryker, S. (1968). Identity salience and role per- formance: The relevance of symbolic interaction theory for family research. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 30, 558–564.

[60]. Petts, R. J., & Knoester, C. (2018). Paternity leave-taking and father engagement. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80(5), 1144-1162.

[61]. Tong, ShaoSu. (1994). Role Confusion and Women’s Way Out--A Review of the International Conference on “Contemporary Role Conflict Research of Working Women”. Zhejiang Journal (01).

[62]. Tong, X., Long, Y.. (2002). Reflection and Reconstruction--A Review of Research on Gender Division of Labor in China. Zhejiang Journal (04).

[63]. Shen Chonglin, Yang Shanhua, and Li Dong. (1999). Urban and Rural Families at the Turn of the Century. China Social Science Press. p91.

[64]. Third Survey on the Social Status of Chinese Women (2011). All-China Women’s Federation and National Bureau of Statistics. Available from: http://www.china.com.cn/zhibo/zhuanti/ch-xinwen/2011-10/21/content_23687810.htm (Accessed19 July 2023 ).

[65]. The world bank (2023). Labor force participation rate, female (% of female population ages 15+) (modeled ILO estimate). Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.FE.ZS (Accessed19 July 2023).