1.Introduction

The Internet has become a platform for rapidly disseminating various events and generating diverse discussions, with an observable trend worthy of attention: the phenomenal flourishing of gender-based antagonism fueled by digital technologies [1]. One significant contributing factor is that the algorithmic shaping of the design, features, and sociality of social platforms such as Weibo and the appropriation of their affordances by users has led to the “platformization of misogyny [2].” In the current digital era, the pervasive influence of gender perspectives has become more pronounced and accessible thanks to the advancements in online technologies and platforms. On the one hand, the development of online technology and platforms has promoted the spread of feminism in China. On the other hand, it has also encouraged hate speech and misogynistic culture [3]. The coexistence of feminist and anti-feminist voices has engendered an expanded public discourse sphere and intensified social ramifications.

The film industry has always been a powerful platform for storytelling and cultural expression. Society is reflected in film, and turn, films influence society through changes in its representations, which have continued for decades [4]. Moreover, because feminism is popular—contemporary feminism circulates in commerce and mainstream media, and the masses can consume it—the film industry increasingly acknowledges and addresses feminist topics driven by commercial interests [5]. While intentionally or not, film production provides a platform for further exploration of feminist topics, stimulates the audience’s engagement, fosters social awareness of gender and political issues, and contributes to the shaping and disseminating of feminism to a certain extent.

China, renowned as one of the world’s largest film markets, is experiencing a growing awareness and discourse surrounding gender-related concerns, encompassing the development of feminism. Even though social media provides a platform for Chinese feminists to voice their opinions, feminist writings, images, performance art, drama, and videos have been subjected to online attacks and abuse [6]. A prominent example of critical discussion is the movie Barbie. With its iconic and influential female protagonists, Barbie currently ranks second in the global box office in 2023. Intriguingly, nearly 80% of Barbie’s Chinese audience comprises females, rendering it a significant case study to examine the focal points and prevailing status of feminism in China. By examining and comparing the film reviews of Barbie on Eastern and Western network platforms, this research aims to conduct in-depth analysis and investigation. At the same time, this study focuses on the presentation and voice of Chinese feminism on online platforms.

The research questions of this paper are as follows:1) What issues do Chinese feminists pay attention to in online comments? What are their main views and reactions? 2) What is the attitude and emotional intensity of feminism among Chinese audiences? What are the barriers and limitations feminists face? 3) What are the similarities and differences between Chinese feminism and Western feminism? 4) Do Chinese audiences have different views on feminist films at home and abroad? What is the difference? Most film reviews were collected from popular online platforms in the East and West to ensure a representative and diverse sample. These reviews provide the study with a broad dataset to analyze and compare the focus and treatment of feminism in the movie Barbie. Besides, this study combines quantitative techniques such as word frequency and sentiment analysis with qualitative topic analysis. The collected data is analyzed and interpreted through various methods and strategies. Delve into these comments using techniques such as word frequency statistics, sentiment analysis, and topic analysis to reveal critical themes, emotional expressions, and common perceptions of feminism in China.

This research stands out from previous work in several key aspects. Firstly, while feminist studies in the past have primarily focused on the development of feminism in Western societies, there is a notable dearth of research on Chinese feminism. This study fills this research gap by examining the critical discourse surrounding Barbie, thereby revealing the focal points and contemporary status of Chinese feminism.

Secondly, this research utilizes a comparative analysis approach, enabling a systematic comparison of feminist perspectives, attitudes, and arguments across different cultural contexts. It aims to uncover shared themes and distinctiveness among these perspectives, thereby contributing to a better understanding of the position and development of Chinese feminism within a global framework. This has significant implications for promoting cross-cultural understanding and facilitating a global dialogue on feminism.

Furthermore, this study analyzes critiques related to Barbie, utilizing comments collected from both Eastern and Western network platforms as the primary data source. This focused approach enables the exploration of specific aspects within a limited scope, distinguishing it from other potential feminist studies.

2.“Feminism” and “Feminist Film”

Feminism as a political movement, including liberal, radical, Marxist, socialist, and other tendencies, only developed in the 20th century [7]. It is a theoretical and social movement that aims to fight for gender equality and address the problem of unequal gender power relations. It focuses on the pursuit of recognition, equality, and freedom of women’s status and rights in the social, political, economic, and cultural spheres. Today, while there is an explosion of popular feminism and a convergence of feminism with neoconservative and neoliberal agendas, grassroots feminism and large-scale feminist protests are re-emerging as a potentially powerful political force. These developments indeed allude to the experience of a feminist renaissance [8].

The feminist film is not only a genre that explores and presents the female experience, gender identity, and gender relations but also provides revelations about how hegemonies concerning gender, race, class, and culture impact individuals’ social identities and lives. It intersects with different sociocultural issues in a diverse environment [9]. It aims to challenge and critique existing gender norms, stereotypes of the female image, and social discrimination against women. Feminist films highlight gender inequality and promote gender equality by telling women’s stories, exploring women’s individual and collective experiences, and focusing on women’s power and identity in society, politics, and culture.

3.Data Collection and Analysis Methods

3.1.Platform Selection and Data Collection

This study used crawlers to collect audience comments on the movie Barbie from four platforms: Douban, Maoyan, IMDB, and Rotten Tomatoes. The collected data consists of two main parts. The first part comprises textual data, which was analyzed to examine the themes discussed in film reviews, the content of concerns, and the expression of emotions. The second part encompasses rating data, that is, the rating of those comment-makers. As of August 31, 2023, a total of 1626 film review texts and 1595 ratings were collected on Douban and Maoyan platforms, while 1442 film review texts and 1171 ratings were collected from the IMDB and Rotten Tomatoes platforms. On average, Chinese comments consisted of 67.41 words, while English comments averaged 147.95 words in length.

The selection of these four platforms as the data sources for this study is based on the following considerations:

Douban is a prominent online platform in China that hosts film and television content, boasting a large and highly engaged user base. This platform primarily focuses on user-generated content, making it an ideal source for collecting diverse audience comments on films.

Additionally, the Maoyan platform is directly associated with movie ticket purchasing services.

This connection allows audiences to leave comments on the platform, following their movie experience conveniently. As a result, the comments gathered from Maoyan are more likely to reflect the opinions and impressions of moviegoers.

Furthermore, IMDB and Rotten Tomatoes are renowned film review websites that attract a broad audience of movie enthusiasts and professional critics alike. The reviews on these platforms derive from genuine viewers, lending them higher authenticity and representativeness.

By utilizing data from these four platforms, this study aims to incorporate a comprehensive range of perspectives from different sources, thereby enhancing the robustness and diversity of the collected data.

3.2.Data Analysis Methods

Once the review dataset is obtained, the text is cleaned and standardized using natural language processing techniques to ensure data accuracy and consistency. Word frequency statistical analysis was used to count and rank the words appearing in the review data to understand the audience’s attention to the movie Barbie. Then, the sentiment analysis technology of ChatGPT4 is used to classify the sentiment of the review text to explore the positive and negative attitudes of the audience towards feminism and the relationship between such attitudes and movie ratings. At the same time, Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) is used to find the potential themes in the comments and reveal the audience’s concerns and views on feminism.

Once the review dataset is obtained, a series of preprocessing steps is performed to ensure data accuracy and consistency using natural language processing techniques. These steps involve cleaning and standardizing the text. Then, sentiment analysis is conducted using ChatGPT4’s sentiment classification technology to classify the sentiment of the review text to explore the audience’s positive and negative attitudes toward feminism and the relationship between such attitudes and movie ratings. Moreover, Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) is employed to identify potential themes within the comments. This analysis identifies underlying topics and helps reveal the audience’s concerns and perspectives regarding feminism.

4.Analysis

4.1.Word Frequency Analysis

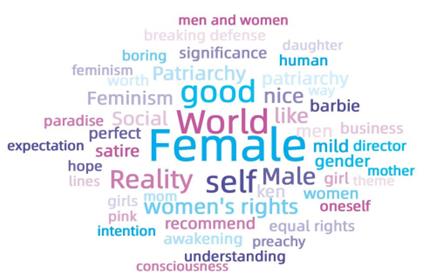

Data analysis is mainly divided into three steps. Firstly, 1625 comment samples were segmented into Chinese words using Python and the Chinese word segmentation database Jieba2, and word frequency was calculated. After eliminating meaningless words such as single words, quantifiers (such as “one”), pronouns (such as “this”), conjunctions (such as “but”), degree words (such as “very”), and words inevitably related to the theme such as “movie” and “Barbie,” the top 50 words with the highest frequency were selected as keywords to generate word cloud maps (Figure 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Word clouds of Barbie movie reviews on Douban and Maoyan.

Among the Chinese comments (Figure 1), “female” (471 times), “self” (272 times), “male” (179 times), “women’s rights” (144 times), “Patriarchy” (125 times), “Feminism” (112 times), and “patriarchy” (100 times) ranked first, third, sixth, seventh, 10th, 12th, and 13th, respectively.

It is worth noting that in Chinese, there is a word that carries the same meaning as feminism but weakens its positive political connotations, thus avoiding any potential “prejudice and misinterpretation” associated with the term “feminism” [3]. This term, translated as “feminism” (with a lowercase “f” as a distinction), is mentioned 45 times in the text.

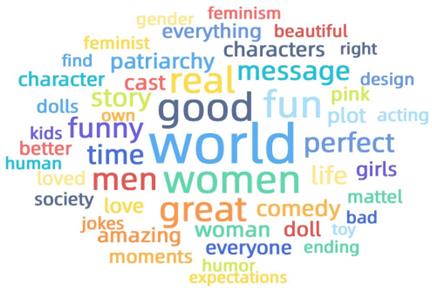

Figure 2: Word clouds of Barbie movie reviews on IMDB and Rotten Tomatoes.

Then, word frequency analysis was conducted on 1442 English comments using Python. In the results (Figure 2), “women” (560 times), “men” (417 times), “woman” (224 times), “patriarchy” (226 times), “gender” (139 times), “feminist” (148 times), and “feminism” (136 times) ranked 2nd, 7th, 16th, 17th, 35th, 43rd, and 45th, respectively.

The results of word frequency show that the discussion topics in the Chinese and English audience comments exhibit a high degree of similarity. In addition to the comments on the film, they all delve into themes concerning gender (“female/women” and “male/men”), patriarchy, and feminism.

However, notable differences emerge between the two:

The words related to gender and feminism in English reviews ranked generally lower than Chinese reviews in terms of word frequency, which shows that audiences in Chinese reviews are more sensitive to the feminist theme of the film and more expressive.

Chinese comments focused more on female gender roles, as words like “mother” and “daughter” appear among the top 50 keywords. At the same time, Chinese critics are more inclined to evaluate the expression of feminism in the film as either “mild” or “ironic”.

It is noteworthy that Chinese reviews more frequently refer to the reactions of male audiences, indicated by the use of the term “breaking defense.”

Breaking defense is a term often used in Chinese online contexts to describe the phenomenon of someone being hit with a vulnerable point and then leading to an emotional breakdown, often resulting in low ratings or negative commentary in movie reviews.

4.2.Sentiment Analysis

4.2.1.Sentiment Distribution

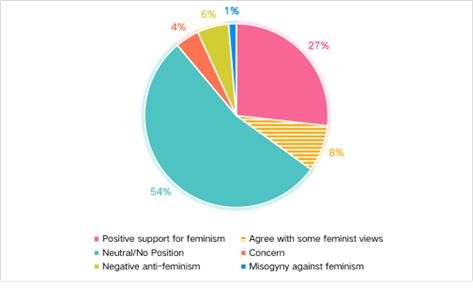

Firstly, the sentiment analysis of the review dataset was conducted using the ChatGPT4 model. This analysis aimed to classify the comments into six distinct emotional categories, namely actively supporting feminism, agreeing with some feminist views, neutral/non position, concern, negative anti-feminism, and misogyny against feminism.

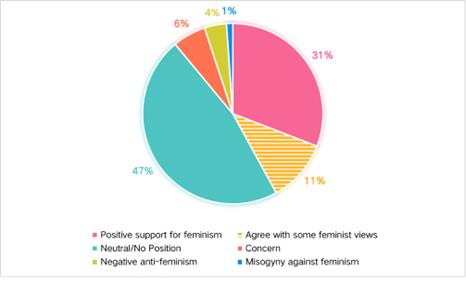

Figure 3: Distribution of sentiment in reviews on Douban and Maoyan.

In the Chinese comment dataset, as shown in Figure 3, 54% of the audience (875 comments) expressed a neutral/no position sentiment. However, among the comments that expressed sentiment toward feminism, more than half of the audience actively supported feminism.

Figure 4: Distribution of sentiment in reviews on IMDB and Rotten Tomatoes.

While in the English comments (Figure 4), there was a noticeably higher percentage of individuals expressing sentiment (53%). Additionally, a more significant proportion of the audience (42%) actively supported feminism or agreed with some feminist views.

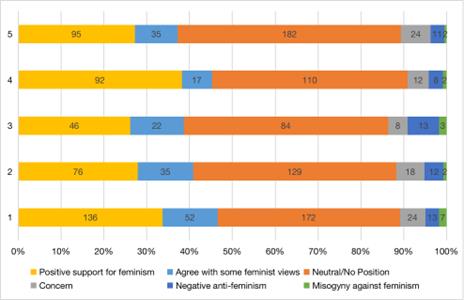

4.2.2.Relationship Between Sentiment Attitudes and Movie Ratings

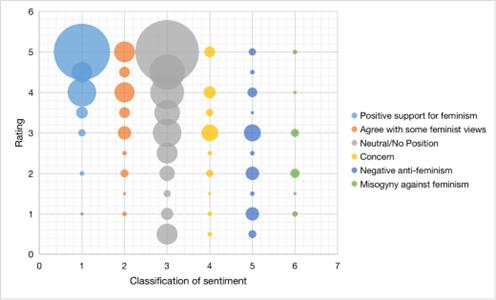

Regarding the impact of sentiment attitudes towards feminism on audience movie ratings, the following two images (Figure 5 and 6) demonstrate the relationship.

Figure 5: Classifications of sentiment and ratings in reviews on Douban and Maoyan.

From the results (Figure 5), it can be observed that the sentiment attitudes of the audience towards feminism have a significant impact on their movie ratings. Commenters who hold positive attitudes towards feminism tend to give higher ratings. This may be because they appreciate the portrayal of strong female characters in the movie and the feminist values it conveys. However, some viewers give relatively lower ratings (2-3 stars) despite having no significant disputes with feminism. Their reasons can be divided into three main aspects:

1. The movie’s depiction of feminism is not profound enough. (“It is too superficial, more suitable for awakening the feminist consciousness of young girls.”)

2. The movie’s plot needs to be more compelling. (“I am not easily pleased by something hastily put together like this. It is a movie, after all, and if it wants to convey values, it should at least establish a convincing story. Otherwise, I might as well watch a more humorous and incisive stand-up comedy.”)

3. Commercial films themselves contradict feminism. (“A ‘self-punishment of patriarchal norms.’”, “Can Hollywood produce truly excellent feminist films? It is difficult, as they cleverly exploit the traps of consumerism...”)

It is worth noting that some Chinese comments rate the movie with five stars, not because the commenters believe the movie deserves the highest rating, but rather to balance out the lower ratings they anticipate from those who do not support feminism. (“Adding an extra star to balance out the breaking-defense males.” “Better than I imagined. It is a four-star movie for me, but because the male’s defense has been broken, I will give it 5 stars.”)

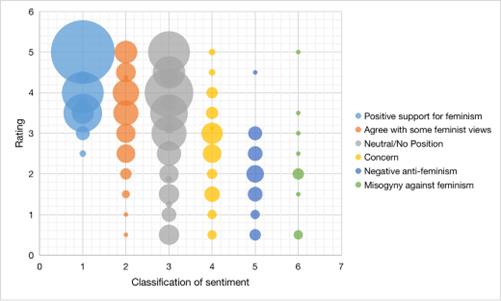

Figure 6: Classifications of sentiment and ratings in reviews on IMDB and Rotten Potatoes.

Unlike Chinese comments, where neutral/no position commenters also significantly tend to give higher ratings to the movie, English comments display a more balanced association between movie ratings and sentiment attitudes towards feminism. Upon reading the comments, it was found that while the high-rating neutral commenters in Chinese comments did not explicitly express their attitudes towards feminism, a considerable portion of them mentioned “men” and “women” and implied specific gender preferences (e.g., “kendom! Men dominate, like to have women serve them tea and water. The most a girl can do is a girl’s night out. Straight men are foolish, haha”, “What kind of people give one star, I will not say,” “The funniest thing is that the men on my right side did not laugh at all, he quickly left when the end credits rolled, so funny”). In contrast, among the neutral commenters in English comments, those who gave lower ratings provided reasons similar to the Chinese comments, while other comments that gave average or higher ratings did not mention sentiment attitudes towards feminism extensively (Figure 6).

One speculation is that the discussion on feminism on the Chinese internet is more generalized, drifting towards the context of gender. Chinese audiences are more inclined to express their gender preferences rather than the political concept of “feminism.” There are historical reasons behind this phenomenon. In China, feminism is often seen as an alien political concept, while indigenous Chinese feminism has no ontological boundaries and has emerged in different forms throughout history [1]. There are also political factors at play. In the current political climate of China, collective feminist movements are generally forbidden, leading feminism to predominantly manifest in a mass online context rather than a purely academic one. This shift provides more opportunities for women-focused Chinese Internet Key Opinion Leaders (Kols) to engage with and influence feminist discourse [10]. Therefore, influenced by the characteristics of internet communication, feminist expressions and viewpoints are often easily simplified into gender perspectives.

In conclusion, when analyzing the Chinese and English reviews of Barbie, it can be observed that the sentiment attitudes of the audience towards feminism have a particular influence on their movie ratings. Commenters with positive attitudes towards feminism are likelier to give higher ratings, while those with different perspectives may provide different ratings. However, this is just a general trend within the audience group, and individual ratings and perspectives on the movie may vary.

4.3.Topic Analysis

The present study utilizes the Gensim library and the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model for topic analysis. The number of topics is set to 5, and each displays seven representative keywords, helping us understand the main content of each topic. These keywords are obtained through model training, representing the vocabulary highly relevant to each topic in the comment texts. Similarly, words that are necessarily related to the movie’s theme (such as “Barbie,” “movie,” and “Ken”) were excluded from the statistical analysis process.

This paper uses the LDA model for each comment to determine its distribution across different topics. Since each comment may be related to multiple topics, this paper chooses to classify it into the topic with the highest probability.

Table 1: Representative keywords for comment topics on Douban and Maoyan.

Topic |

Keywords |

1 |

0.017*“women” + 0.013*“men” + 0.010*“world” + 0.006*“good” + 0.005*“reality” + 0.004*“feminism” + 0.004*“society” |

2 |

0.014*“men” + 0.008*“women” + 0.007*“like” + 0.006*“reality” + 0.005*“plot” + 0.004*“world” + 0.004*“Patriarchy” |

3 |

0.019*“women” + 0.010*“world” + 0.008*“men” + 0.006*“Patriarchy” + 0.006*“reality” + 0.005*“plot” + 0.004*“become” |

4 |

0.008*“women” + 0.006*“men” + 0.006*“plot” + 0.006*“nice” + 0.005*“reality” + 0.005*“feminism” + 0.005*“world” |

5 |

0.013*“good” + 0.008*“women” + 0.008*“great” + 0.007*“world” + 0.005*“like” + 0.005*“plot” + 0.004*“recommend” |

According to the representative keywords (Table 1), it can be seen that the themes of comments mainly revolve around three aspects:

1. Gender roles and social cognition: The presence of words such as “women” and “men” indicates a focus on gender roles and social cognition.

2. Social reality and feminist consciousness: Words such as “world,” “reality,” “feminism,” and “society” suggest that Barbie is related to social reality and feminism advocacy.

3. Plot and film evaluation: Words such as “plot,” “good,” “great,” and “recommended” primarily pertain to the plot development and audience evaluation of the film.

Due to the limited sample size, the keywords of each topic may exhibit little differences. However, they can still be analyzed in terms of their weight distribution.

Theme 1 highlights the roles of women and men and their relevance to social and real-world situations. Theme 2 and Theme 3 emphasize male and female roles, respectively, and discuss the patriarchal system. The weight distribution of theme 4 keywords is relatively even, while theme 5 highlights the viewing experience and evaluation of the movie.

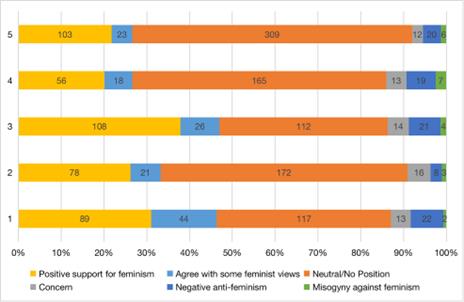

Figure 7: Topic distribution and sentiment classification of comments on Douban and Maoyan.

Furthermore, according to Figure 7, it can be observed that the proportion of neutral comments in theme 5 is the largest among the five themes, which corresponds to its keywords focusing on the viewing experience and narrative structure of the film.

Table 2: Representative keywords for comment topics on IMDB and Rotten Tomatoes.

Topic |

Keywords |

1 |

0.012*“women” + 0.009*“fun” + 0.006*“perfect” + 0.006*“story” + 0.005*“message” + 0.005*“funny” + 0.004*“land” |

2 |

0.010*“fun” + 0.009*“funny” + 0.006*“women” + 0.006*“plot” + 0.005*“message” + 0.005*“characters” + 0.004*“loved” |

3 |

0.006*“women” + 0.006*“fun” + 0.005*“message” + 0.004*“comedy” + 0.004*“patriarchy” + 0.004*“feminist” + 0.004*“funny” |

4 |

0.011*“women” + 0.009*“perfect” + 0.007*“fun” + 0.005*“funny” + 0.004*“patriarchy” + 0.004*“doll” + 0.004*“message” |

5 |

0.008*“fun” + 0.007*“women” + 0.006*“comedy” + 0.006*“story” + 0.006*“message” + 0.005*“character” + 0.004*“amazing” |

The representative keywords of comments on IMDB and Rotten Tomatoes (Table 2) demonstrate a similar focus on women as seen the Chinese comments, alongside discussions about patriarchy and feminism. Both express an interest in the portrayal of women in Barbie, development of female characters, and women-related issues. However, a notable difference is the absence of mentions of men in English reviews. This indicates that in Chinese cultural context, feminism is highly associated with men (as the opposite gender), which is confirmed by the phenomenon --Chinese comments exhibiting a distinct focus on the reaction of male audiences to the film. This, to some extent, reflects a stronger sense of opposition.

Additionally, the English review emphasized the comedy and entertainment value of the film, with keywords like “fun” and “funny” present in every theme. This suggests that western reviewers pay more attention to the comedic elements, sense of humor and the overall entertainment experience when evaluating the movie. This may also explain why the distribution of emotional attitudes across different themes in English reviews is not as distinct as in Chinese reviews.

Figure 8: Topic distribution and sentiment classification of comments on IMDB and Rotten Tomatoes.

It is worth noting that theme 3 and theme 4, which both mention patriarchy, exhibit contrasting attitudes, as shown in Figure 8. Theme 3 has the largest proportion of individuals who are negatively anti-feminism and misogyny against feminism, while theme 4 has the largest proportion actively supporting feminism among the 5 themes. One possible explanation is that when it comes to political and ideological concepts, people’s emotional attitudes tend to become more intensified and polarized, which is the “ideologisation” of today’s growing phenomenon of affective polarization [11]. After reading the comments, it is found that negative comments on feminism in Theme 3 primarily stem from they think the film is too extreme, too political, and potentially sexist, while some others argue that the film’s portrayal of feminism is outdated and superficial.

5.Discussion

To examine the potential divergent attitudes and perspectives of Chinese audiences towards domestic and foreign feminist films, this research collected 200 comments for 10 films from the Douban platform. The selected films consisted of domestic feminist films, namely Ghost Love, Send Me to the Clouds, Spring Tide, The Crossing, and Balloon, as well as foreign feminist films, namely Barbie, Thelma and Louise, The Desert Flower, Hidden Figures, and Kim Ji-young, Born 1982.

Following data processing and Chinese word segmentation, a word frequency analysis was conducted on the dataset consisting of 2000 comments.

Table 3: Word frequency table of domestic feminist films.

Words |

Frequency |

Words |

Frequency |

Words |

Frequency |

Female |

345 |

Like |

102 |

Monologue |

76 |

Director |

265 |

Life |

100 |

Performance |

75 |

Self |

177 |

Male |

98 |

Narrative |

74 |

Balloon |

157 |

Expression |

92 |

Men |

68 |

Table 3: (continued).

Story |

152 |

Women |

90 |

Actors |

66 |

Mother |

130 |

Reality |

89 |

World |

64 |

Characters |

129 |

Youth |

83 |

Daughter |

59 |

Family |

124 |

China |

81 |

Lines |

59 |

characters |

112 |

Zhong Kui |

80 |

Conflict |

58 |

Relation |

108 |

Hong Kong |

79 |

||

Shot |

106 |

Society |

78 |

Table 4: Word frequency table of foreign feminist films.

Words |

Frequency |

Words |

Frequency |

Words |

Frequency |

Female |

477 |

Freedom |

65 |

Like |

49 |

Self |

156 |

Black people |

62 |

Family |

47 |

Male |

151 |

Feminism |

59 |

Subject Matter |

46 |

World |

137 |

True |

58 |

characters |

45 |

Society |

135 |

Life |

56 |

Patriarchy |

44 |

Women |

115 |

Husband |

55 |

husband |

44 |

Reality |

109 |

Mother |

55 |

South Korea |

43 |

Story |

96 |

Gender |

54 |

Daughter |

42 |

Men |

92 |

Problem |

50 |

Perfect |

41 |

Women’s rights |

83 |

Mom |

50 |

Ending |

41 |

According to the word frequency analysis results (Table 3 and 4), this paper can draw some conclusions about the similarities and differences in Chinese people’s comments on domestic and foreign feminist films.

For domestic feminist films, the most frequently used words include “female,” “director,” “myself,” “balloon,” “story,” “mother,” “character,” “family,” “role,” and “relationship.” These indicate that reviewers are concerned about female themes, family relationships, character development, and interpersonal connections within the films. Additionally, specific words such as “China,” “Hong Kong,” “society,” and “reality” suggest that reviewers are making connections between the films and the Chinese social and cultural context.

In contrast, for foreign feminist films, the most frequently used words include “female,” “film,” “self,” “men,” “world,” “society,” “women,” “reality,” and “story.” This reflects reviewers’ concerns about female themes, social reality, and gender relations portrayed in the films. Specific terms like “women’s rights,” “freedom,” “black,” and “feminism” indicate reviewers’ focus on women’s rights, social progress, and pluralism.

By comparing the two sets of comments, we see differences between Chinese audiences’ comments on domestic and foreign feminist films. In domestic feminist films, reviewers pay more attention to family and social relationships and issues tied to the Chinese social background. On the other hand, reviewers emphasize global social issues and women’s rights and interests for foreign feminist films.

However, both sets of comments focus on individual subjectivity and self-exploration, as evidenced by the frequent use of the word “self.” This suggests that reviewers highly value the personal growth and development of characters in the films.

Moreover, word frequency statistics reveal reviewers’ similar attitudes toward the films’ captivating stories, character developments, and audio-visual presentations. Whether discussing domestic or foreign feminist films, reviewers express a certain degree of admiration and concern for the authenticity and life presented in the films and the social issues they address.

6.Conclusion

This study comprehensively analyzed a dataset comprising Chinese and English comments. Valuable insights into the expressed opinions and attitudes were gained through various analytical techniques, including word frequency analysis, sentiment analysis, and topic analysis. Word frequency analysis revealed common themes discussed by both Chinese and foreign audiences, such as gender, patriarchy, and feminism. However, notable variations were observed in these themes, with Chinese comments being more sensitive to the feminist themes of the movie, more focused on female gender roles, and more expressive in their commentary. The results of sentiment analysis indicated that half of the Chinese comments exhibited neutral emotions, with a certain percentage implying gender preference. Additionally, a positive correlation was observed between sentiment attitudes and movie ratings, suggesting that more positive emotions are associated with higher movie ratings. Furthermore, topic analysis provided a deeper understanding of the underlying themes prevalent in the comments. The presence of the representative keyword “men” in Chinese comments, while absent in English comments, suggests that Chinese feminism exhibits a stronger sense of opposition in terms of gender. By conducting these analyses, a comprehensive comprehension of the opinions and attitudes expressed by Chinese and foreign audiences in movie comments was achieved. The research findings highlight the significance of accounting for cultural disparities and subtle linguistic nuances when analyzing and interpreting user-generated content. The results can provide valuable insights for further understanding the status and development of feminism in China.

References

[1]. Angela Xiao Wu & Yige Dong (2019) What is made-in-China feminism(s)? Gender discontent and class friction in post-socialist China, Critical Asian Studies, 51:4, 471-492, DOI: 10.1080/14672715.2019.1656538.

[2]. Liao, S. (2023). The platformization of misogyny: Popular media, gender politics, and misogyny in China’s state-market nexus. Media, Culture & Society, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437221146905.

[3]. Lihua GAN.(2021).Patriarchy, Networked Misogyny, and Interpreting Feminism in China. Communication and Society, 57 (2021), 159-190.

[4]. Mo Xu.(2021).Analysis on the Influence of Female Characters in Disney Films.Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 571, 327-331, DOI:10.2991/assehr.k.210806.061.

[5]. Sarah Banet-Weiser & Laura Portwood-Stacer (2017) The traffic in feminism: an introduction to the commentary and criticism on popular feminism, Feminist Media Studies, 17:5, 884-888, DOI: 10.1080/14680777.2017.1350517.

[6]. Qiqi Huang (2022) Anti-Feminism: four strategies for the demonisation and depoliticisation of feminism on Chinese social media, Feminist Media Studies, DOI: 10.1080/14680777.2022.2129412.

[7]. MICHELLE FRIEDMAN, JO METELERKAMP & ROS POSEL (1987) What Is Feminism?, Agenda, 1:1, 3-24, DOI: 10.1080/10130950.1987.9674671.

[8]. Banet-Weiser, S., Gill, R., & Rottenberg, C. (2020). Postfeminism, popular feminism and neoliberal feminism? Sarah Banet-Weiser, Rosalind Gill and Catherine Rottenberg in conversation. Feminist Theory, 21(1), 3-24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700119842555.

[9]. Ai, Yiran (2022). What makes a film feminist?: gender perspectives of directors of westernised and Hong Kong cinema between 1990 and 2000. University of Birmingham. Ph.D..

[10]. Altman Yuzhu Peng (2021) Neoliberal feminism, gender relations, and a feminized male ideal in China: a critical discourse analysis of Mimeng’s WeChat posts, Feminist Media Studies, 21:1, 115-131, DOI: 10.1080/14680777.2019.1653350.

[11]. Lilliana Mason, Ideologues without Issues: The Polarizing Consequences of Ideological Identities, Public Opinion Quarterly, Volume 82, Issue S1, 2018, Pages 866-887, https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfy005.

Cite this article

Huang,J. (2023). Comparative Analysis: The Development of Chinese Feminism Based on East and West Barbie Film Reviews. Communications in Humanities Research,22,51-63.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Angela Xiao Wu & Yige Dong (2019) What is made-in-China feminism(s)? Gender discontent and class friction in post-socialist China, Critical Asian Studies, 51:4, 471-492, DOI: 10.1080/14672715.2019.1656538.

[2]. Liao, S. (2023). The platformization of misogyny: Popular media, gender politics, and misogyny in China’s state-market nexus. Media, Culture & Society, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437221146905.

[3]. Lihua GAN.(2021).Patriarchy, Networked Misogyny, and Interpreting Feminism in China. Communication and Society, 57 (2021), 159-190.

[4]. Mo Xu.(2021).Analysis on the Influence of Female Characters in Disney Films.Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 571, 327-331, DOI:10.2991/assehr.k.210806.061.

[5]. Sarah Banet-Weiser & Laura Portwood-Stacer (2017) The traffic in feminism: an introduction to the commentary and criticism on popular feminism, Feminist Media Studies, 17:5, 884-888, DOI: 10.1080/14680777.2017.1350517.

[6]. Qiqi Huang (2022) Anti-Feminism: four strategies for the demonisation and depoliticisation of feminism on Chinese social media, Feminist Media Studies, DOI: 10.1080/14680777.2022.2129412.

[7]. MICHELLE FRIEDMAN, JO METELERKAMP & ROS POSEL (1987) What Is Feminism?, Agenda, 1:1, 3-24, DOI: 10.1080/10130950.1987.9674671.

[8]. Banet-Weiser, S., Gill, R., & Rottenberg, C. (2020). Postfeminism, popular feminism and neoliberal feminism? Sarah Banet-Weiser, Rosalind Gill and Catherine Rottenberg in conversation. Feminist Theory, 21(1), 3-24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700119842555.

[9]. Ai, Yiran (2022). What makes a film feminist?: gender perspectives of directors of westernised and Hong Kong cinema between 1990 and 2000. University of Birmingham. Ph.D..

[10]. Altman Yuzhu Peng (2021) Neoliberal feminism, gender relations, and a feminized male ideal in China: a critical discourse analysis of Mimeng’s WeChat posts, Feminist Media Studies, 21:1, 115-131, DOI: 10.1080/14680777.2019.1653350.

[11]. Lilliana Mason, Ideologues without Issues: The Polarizing Consequences of Ideological Identities, Public Opinion Quarterly, Volume 82, Issue S1, 2018, Pages 866-887, https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfy005.