1.Introduction

In the discussion of the Yuan court’s attitudes toward different cultures, historian Zhan defined Yuan’s attitudes towards Han culture as the delay of the assimilation with Han culture in his analysis of the characteristics of the Mongol Yuan [1]. Germany Herbert Franke also stressed Han culture and Tibetan Buddhism as tools of the Mongols to govern their expansive land, rather than completely adopting into them [2]. However, these two conclusions both focused on Mongol Yuan’s politics and ideologies but disregarded their absorption in materials, especially in textiles. From this panel, various cultural elements were shown on this imperial textile to resist extant theories that set the Yuan court in their original culture or treat their adaptation extremely functionally. This research on Yuan Tuan Feng tattoo piece aims to make up for the lack of studies focusing on a particular silk textile work because silk is corrosive and has to be reserved for several centuries. Most extant studies on Yuan textiles stress sorting and summarizing motif features and resources, rather than analyzing them in a whole work. Here, a silk panel from the 14th Yuan Dynasty could be explained overall from its motifs and where they came from, its colors and techniques, and who had mastered them. Based on ancient Chinese poems and historical records, Textile Pattern Studies in the Yuan Dynasty and Flight of the Phoenix: Crosscurrents in Late Thirteenth- to Fourteenth-Century Silk Patterns and Motifs, this paper analyzes the multi-cultural elements in the Silk Work Panel with Yuan Tuan Feng and gives insight into the tolerant and contradictory attitude of the Mongolian meta-nobility towards the multi-culture under its rule.

2.Yuan Tuan Feng tattoo piece

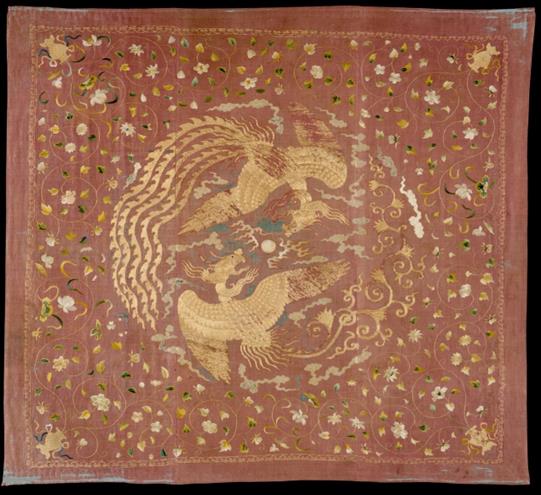

The red square silk board shown in Figure 1 was made in the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368) and now is in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum. To the fledging eye, silk panel 1988.82 looks intriguing: it is overly red, with golden thread embroidery, various small flowers and leaves surrounding and two golden phoenixes flying around a circular stone like a jade. The silk panel seems distinctive from any silk textile: its colorful decoration is unlikely to any other light-color plain silk form of the Song Dynasty (960-1279), differs from high-contrast colors of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), and is used as a tent decoration. It would require an overall look at the silk panel to see that the pattern of the textile is similar to the Islam textile in its pattern structure, with a Taoism symbol, Buddhist lotus, and Mongolian nomadic totems.

Figure 1: Panel with phoenixes and flowers.

3.Phoenix pattern

According to Figure 1, a couple of gold energetic phoenixes are looking at each other and flying around a circular stone up and down. The overall structure of the circular compartment formed by the tails of the two phoenixes is a combination of traditional Chinese motifs and Mongolian designs.

3.1.The head of phoenixes in north prairie culture and Han culture

Paired phoenixes are traditional Chinese motifs widely used in clothing weaving, representing the love of the married couple. In Greater Odes of the Kingdom in the Book of Song, the male and the female phoenix symbolizes the King of Zhou when phoenixes were an image of noble and sagacious man. In later Chinese literature, the phoenix is the symbol of true love. With the bolstering of the weaving textile business with the Near East and the West since the Tang Dynasty, the phoenix has been regarded as a typical Han culture motif in the tapestry. In fact, ancient ethnics also treated phoenixes as divine birds and applied them in their decoration. For example, as depicted in Figure 2, the Liao craftsman added a phoenix to the crown of the princess to explicit the noble status. The paired phoenixes in the middle of the textile are a mixture of the features of nomadic and Han phoenixes from their designs of heads to tails. The Liao gold phoenix on the princess’s crown has an eagle-like head with an opening sharp bill and a pair of fierce eyes, which differs from the Han traditional one with gentle eyesight and a chick-like bill.

Figure 2: Gold phoenix royal crown of liao princess [3]

The Liao phoenix design was introduced and contributed by North Shamanism and North Wei’s Buddhism. In the analysis of Zhang, the motifs of dragon and phoenix were brought by Tang’s princess in their marriage with the Khitan tribe, when Han culture started to influence the northern nomadic culture. Instead of throughout absorption of Han’s motif, nomadic culture has recreated them based on their Shamanism. In the legend of Shamanism, the eagle is the symbol of light and fire to frame the night and fight with fires, as the incarnation of Shamaness [4].

3.2.The gender implied in the phoenixes’ tails

The shapes of these phoenixes’ tails are Mongolian and vary in the number of feathers. In ancient China, male phoenixes were called “Feng”, while female ones were “Huang”, according to Erya, the extant earliest Chinese dictionary. In the story of the Han poet Sima Xiangru (179-113BCE), phoenixes were distinguished by gender, the male phoenix called “Feng” and the lady phoenix called “Huang”. In the later development, phoenixes have been regarded as a female symbol. In the Song Dynasty with the popularity of the combination of dragons and phoenixes, the phoenix was treated as female and the dragon represented male. In the research of Yuan Phoenixes by Liu, in the Tang Dynasty and the Ming Dynasty, phoenixes generally had no gender distinguishment with many tails [5]. With the population pattern of dragon and phoenix, the phoenix represents a female with long tail feathers. However, in the Yuan decorations from porcelains to textiles, a male phoenix with a scroll tail feather could be found. In this panel with phoenixes and flowers, the paired phoenixes are flying up and down surrounding the circular stone. The one at the top is a classical female phoenix with many feathers applied in the combing pattern with a dragon, while the bottom one with a single scroll tail feather is a unique sculpt, rarely in Chinese traditional motifs. The design of the male phoenix is Islamic. Islamism rapidly developed in China during the Mongol Empire. With Moslems participating in the Yuan’s conquest of Asia, they were treated as Semu, Second-class citizens, higher than Han people, in the Yuan Dynasty. Yuan set up Hadi department to govern Islamism. According to D’Ohsson’s recording in his research on Mongolian History, provincial and the same class offices designated Mongols and foreigners as their captains including Moslem, Christians, and Buddhists [6]. In addition, because of the captured craftsmen from the Near East, Islamic motifs have been pervasive in the Yuan weaving. Male phoenixes with a single scroll tail feather were one of these Islamic motifs that have already existed in Islamic textiles. On an Islamic ivory box decorated with floral and animal motifs collected by Musée national des Arts asiatiques-Guimet, there is the pattern of a divine bird with an “S” shape scroll tail like a curved grass, resembling the male phoenix in this Yuan panel.

3.3.Xixiangfeng structure and Taoism

Besides the appearance of the paired phoenixes, their position and structure in this textile are worthy to scrutinize. The upper phoenix has five long feathers while the below one has a single scroll tail. This design adopts Han’s “xixiangfeng” structure, an up-down pattern fabrication in a circular medallion. The earliest “xixiangfeng design” was found in the Tang decoration as a kind of spiral circle. The fashion of Taoism cemented the prevalence of this motif in decoration. The spiral originated from the pattern of yin-yang taiji in Taoism. Tang bird-and-flower paintings neatly utilized this spiral to show the vivid activities in nature. The routine was hesitated and improved by the Song painters and adopted with moral purposes. Xixifeng expanded Chinese art expression of nature, replacing previous null standing postures in art works. In Anne Wardwell’s discussion about the phoenix in thirteenth to fourteenth-century silk patterns and motifs, she mentioned Chinese Yuan central phoenixes were in energetic flight, while the serene pair in the Near East works fringing a floral motif [7].

Flighting was a significant feature that made Chinese phoenixes different from Near Eastern phoenixes. “Xixiangfeng” where the paired eyes meet and fly around each other, is not only a yin-yang formulation in Taoism but also a fabulous expression of affection. It has also been applied in other paired postures like a combination of dragons and phoenixes in the Yuan Dynasty. Thus, it could be detected that this structure that comes from Han culture prevailed in the decoration of Yuan.

4.Floral patterns

Floral and leaf patterns at the edge of Yuan Tuan Feng tattoo piece are also manifest elements that imply Yuan’s tolerance of current various cultures and regions. The four primary kinds of flowers in the work are lotus, peony, plum blossom, and water grass.

4.1.One year scene” and Han culture

This motif combination including various flowers comes from the “one year scene”, a fashion among the South Song noble women. Lu You mentioned it in Laoxue'an biji. At the beginning of the Jingkang era (1126-1127AD), in the capital city, the weaves of silk, women’s jewelry, and clothes patterns, were all prepared for the four seasons. For example, the festive object patterns are spring banners, lanterns, racing boats, aihu (Dragon Boat Festival pattern), and cloud moon pattern, and the flowers are peaches, apricots, lotus, chrysanthemums, and plum blossoms. They are all combined into one scene, which is called one year scene. But the Jingkang era (Emperor Qinzong’s Reign) really ended in one year, sure enough, strange fashions will herald changes in the world. After being banned by Song, this design was resuscitated in Yuan and has expanded in clothing. In 1955, in dismantling the twin towers of Beijing Qingshou Temple where Mongolian Buddhism State Teacher Yunhai and his disciple Ke’an were burnt, there was a cloth-wrapped with dragon embroideries with lotus, peony, Paeonia lactiflora and chrysanthemum at the corns, also Chinese characters as “xianghuagongyang” (flower puja).

4.2.The lotus in Buddhism and Han culture

The remarkable thing is that all the flowers in the silk textile are not Mongolian original flowers but are pervasive in Han culture and Buddhism. The lotus implies the Yuan nobility’s worship of Buddhism. In many Yuan Buddhism silk textiles treated lotuses as an important element to show the concept of “Sukhavati”. Before Yuan, lotus has been gradually adopted into the Han literati’s work. Since the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420-589), Buddhism has thrived with the support of the nobility, the lotus has been used in Buddhist Statues, and murals, and has been glorified by the literati who followed the teachings of Buddha. Until the Tang when Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism had been converging, the lotus became a typical symbol in Chinese culture from literature to painting. In the Song Dynasty, the lotus was appropriated into Neo-Confucian cosmology as a significant image in its discussion of the Mind and Human Nature [8], with the development of silk weaving, exquisite and various lotus motifs prevailed in silk textiles. Thus, it can be said that the lotus in this panel symbolizes the Yuan court’s worship of Buddhism, while it should be admitted the high-level motif design was from Han culture.

4.3.Peony and plum blossoms in Han culture

Peony and plum blossoms have a long cultivated and popular cultural history in China before the Yuan. The peony is a Chinese narrative flower with abundant and broad petals, representing richness and productiveness. In the narrative of Song Zhou Dunyi’s On the Love of the Lotus, since the Tang Dynasty of the imperial Li family, everyone has been enamored of the peony. Plum blossom as one of “the three friends of winter” was associated with the spirit of endurance, perseverance, and rejuvenation in the literati’s work. The Nogeoldae ('Old Cathayan') took notes for a motif: bees flying around plum flowers against green grassland [9]. These two floral motifs convey the nobility’s wish to be rich, persevere, and rejuvenate. Entangled floral branches connect all the flowers on this panel, branches tangling all over the ground through broken branches. While there had been interlocked lotus and peonies in textiles in Song, this motif with small flower heads was influenced by Islamic arabesque that promoted Chinese Persian textiles in the Mongol court [10]. The treasure bottles at the four corners and the ruyi cloud surrounding the phoenixes are Buddhist auspicious patterns, having been embroidered in Song and becoming a fashion since Yuan’s support of Tibetan Buddhism.

5.Colors

5.1.Red and Mongolian shamanism

Red and gold are the main colors widely used in imperial artwork and decoration. According to Yuan Shi, the red silk textile with gold weaving was commonly applied as traditional Mongolian sacrificial offerings in their significant ritual for worshiping their ancestors Chinggis Khan [11]. Previous research often regarded redness, a popular color in clothing and decoration in the Yuan dynasty, as Mongolian Yuan’s worship on fire in their Shamanism or their fellowship for Tibetan Buddhism, as found in official recordings. However, as Christopher P. Atwood pointed out religious symbols, the fire cult has already occurred in Mongolian nomadic culture with a ritual to contact tents and families with the world based on fire and state, the people of house with powerful ancestors of the world to bring the house and family thrive and indestructible. The explanation of the fire cult in the family also matches the phoenix pattern in the textile, which implies harmony in a fresh family. Atwood explicated that this fire cult is far from sectarianism which recreate the family itself as a scene of strife [12]. Therefore, this fire cult, and redness cult results from Mongolian nomadic nature, instead of a religious cult in Shamanism or Buddhism.

5.2.Gold and Mongolian culture

The gold threads are one of the most important elements to show the wealth and status of the Mongolian user whose passion for gold is common for nomadic people. The Mongol noble intended to display their wealth via gold and considered gold as a material containing recondite cosmology [13]. Chinggis Khan vowed to dress up the woman in his family with gold clothing on Altay Mountain [14]. Chinggis Khan and his descendants also called themselves Altan Urugh (Gold Family). With the Mongol conquest, the sources of gold expanded from Yunnan, and Tibet, to Central Asia which materially supported gold consummation.

6.Official limitations on the folk use of phoenix patterns and gold weaving

Although the Mongols adapted themselves to the various cultures, these technologies and motifs could be applied in their limitation to show off their imperial status. Weaving golden thread on silk having been popular among the people in the South Song Dynasty could serve the nobility. This textile with golden phoenixes must be possessed by the Yuan Mongolian nobles, because of the Yuan’s strict limits on personal use of gold weaving, as Yuan Dianzhang (The Collection of Laws of the Yuan Dynasty) recorded that besides official textile bureaus, ordinary people should not produce silk with gold weaving. Existing golden weaving silk should be recorded with stamps for sale [15]. The ban had been exacted since 1270 with more severe details in the next decade. Unfortunately, the phoenix motif could not be added to normal clothes yet, in the law of Yuan. Although the Yuan court’s favor of various cultures improved cultural appropriation in the artwork, its strict limitation in gold weaving restricted multi-culture improvement out of the court and left people with a narrow attitude towards other cultures.

7.Conclusion

This paper first illustrates multicultural elements in Yuan Tuan Feng tattoo piece. This imperial decoration consists of diverse Buddhist and Han motifs, and Islamic gold-weaving techniques and does have the ability to reveal the Yuan nobility’s opening attitude towards other cultures. The history of Pre-Yuan Mongolian weaving further explains that the Yuan leader realized their undeveloped material life and desire to absorb others to improve themselves by saving Islamic craftsmen and building a weaving bureau. The analysis verified the Mongol-Yuan was willing to absorb other cultures into their decoration and material life, rather than instrumentalizing them for continuing conquer.

However, as there is little information about the Yuan Tuan Feng tattoo piece, its specific possessor and purpose cannot be determined. Moreover, this paper merely limits to the cultures from where the Yuan conquered, lacking the connection with the West and the Near East which had close commercial intercourse in the 13th and 14th centuries. In the future, more information will be collected based on new archeologic findings and a global perspective will be added.

References

[1]. Zhang Fan (2018) Characteristics of the Yuan dynasty: Reflections on several issues from Mongol Yuan history, Chinese Studies in History, 51:1, 51-69, DOI: 10.1080/00094633.2018.1466564

[2]. Herbert Franke (1994) From Tribal Chieftain to Universal Ruler and God, China under Mongolian Rule, Variorum, pp.33.

[3]. Liu Keyan (2015) Yuan Dynasty Textile Pattern Research [Doctoral dissertation, DongHuaUniversity]. pp.163.

[4]. Zhang Zhengxv (2010). The Analysis of Dragon and Phoenix Motifs on Liao Antiques, Collection of Song Dynasty Studies, (00), 300-314. DOI: 10.16764/b.cnki.ssyjlc.2010.00.042.

[5]. Liu Keyan (2015) Yuan Dynasty Textile Pattern Research [Doctoral dissertation, DongHuaUniversity]. pp.175.

[6]. d’ Ohsson, Abraham Constantin Mouradgea (2008). Histoire des Mongols: depuis Tchinguiz-Khan jusqu’à Timour-Lang. Paris: Didot, Volume One, (Feng Chengjun, Trans) Century Publishing Group of Shanghai, pp.324.

[7]. Wardwell, A. E. (1987) Flight of the Phoenix: Crosscurrents in Late Thirteenth- to Fourteenth-Century Silk Patterns and Motifs. The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art, 74(1), 2–35. pp.14.

[8]. Guo Rongmei (2007) Lotus Flower as a Symbol of Literal Image from Pre-qin to Song (Master’s dissertation, Nanjing Normal University), pp.218.

[9]. Liu Jian, Jiang Shaoyu & Hu Shuangbao (1990) The Nogeoldae, Jin dai Han yu yu fa zi liao hui bian, Shang wu yin shu guan: Xin hua shu dian Beijing fa xing suo fa xing, vol.3 pp.281-282.

[10]. Gray, B. (1985). The Lotus and the Dragon. London, British Museum. The Burlington Magazine, 127(986), 313–303. pp. 313. http://www.jstor.org/stable/882082

[11]. Song, Liang (1976). Yuan Shi, Zhonghua Book Company, vol.77. pp.1924.

[12]. Atwood, C. P. (1996). Buddhism and Popular Ritual in Mongolian Religion: A Reexamination of the Fire Cult. History of Religions, 36(2), 112–139. pp. 126. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3176686

[13]. Allsen, T.T. (2002). Commodity and exchange in the Mongol empire a cultural history of Islamic textiles. Cambridge Cambridge Univ.Press, pp.37.

[14]. Shang Gang. (2003). Nashishi in China, Southeast Culture (08),54-64. pp.59.

[15]. Chen, Gaohua, & Zhang Fan, & Liu Xiao, Duan pi jin zhi long feng duan pi, Yuan Dianzhang Zhouhua Book Company.

Cite this article

Meng,H. (2024). Multicultural Elements of the Mongol-Yuan Silk Textile. Communications in Humanities Research,25,278-284.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Zhang Fan (2018) Characteristics of the Yuan dynasty: Reflections on several issues from Mongol Yuan history, Chinese Studies in History, 51:1, 51-69, DOI: 10.1080/00094633.2018.1466564

[2]. Herbert Franke (1994) From Tribal Chieftain to Universal Ruler and God, China under Mongolian Rule, Variorum, pp.33.

[3]. Liu Keyan (2015) Yuan Dynasty Textile Pattern Research [Doctoral dissertation, DongHuaUniversity]. pp.163.

[4]. Zhang Zhengxv (2010). The Analysis of Dragon and Phoenix Motifs on Liao Antiques, Collection of Song Dynasty Studies, (00), 300-314. DOI: 10.16764/b.cnki.ssyjlc.2010.00.042.

[5]. Liu Keyan (2015) Yuan Dynasty Textile Pattern Research [Doctoral dissertation, DongHuaUniversity]. pp.175.

[6]. d’ Ohsson, Abraham Constantin Mouradgea (2008). Histoire des Mongols: depuis Tchinguiz-Khan jusqu’à Timour-Lang. Paris: Didot, Volume One, (Feng Chengjun, Trans) Century Publishing Group of Shanghai, pp.324.

[7]. Wardwell, A. E. (1987) Flight of the Phoenix: Crosscurrents in Late Thirteenth- to Fourteenth-Century Silk Patterns and Motifs. The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art, 74(1), 2–35. pp.14.

[8]. Guo Rongmei (2007) Lotus Flower as a Symbol of Literal Image from Pre-qin to Song (Master’s dissertation, Nanjing Normal University), pp.218.

[9]. Liu Jian, Jiang Shaoyu & Hu Shuangbao (1990) The Nogeoldae, Jin dai Han yu yu fa zi liao hui bian, Shang wu yin shu guan: Xin hua shu dian Beijing fa xing suo fa xing, vol.3 pp.281-282.

[10]. Gray, B. (1985). The Lotus and the Dragon. London, British Museum. The Burlington Magazine, 127(986), 313–303. pp. 313. http://www.jstor.org/stable/882082

[11]. Song, Liang (1976). Yuan Shi, Zhonghua Book Company, vol.77. pp.1924.

[12]. Atwood, C. P. (1996). Buddhism and Popular Ritual in Mongolian Religion: A Reexamination of the Fire Cult. History of Religions, 36(2), 112–139. pp. 126. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3176686

[13]. Allsen, T.T. (2002). Commodity and exchange in the Mongol empire a cultural history of Islamic textiles. Cambridge Cambridge Univ.Press, pp.37.

[14]. Shang Gang. (2003). Nashishi in China, Southeast Culture (08),54-64. pp.59.

[15]. Chen, Gaohua, & Zhang Fan, & Liu Xiao, Duan pi jin zhi long feng duan pi, Yuan Dianzhang Zhouhua Book Company.