1. Overview of Healing Gardens

Healing gardens, also known as healing gardens or therapeutic landscapes, emerged in the 1990s in the United States and are considered a distinctive form of landscape. The concept is also referred to as healthy gardens, convalescent gardens, or medical gardens.

It is widely believed that the origin of Healing gardens can be traced back to ancient times in countries like the United States and the United Kingdom. For instance, ancient Egyptian physicians prescribed walks in gardens for pharaohs [1]. Ancient Greeks advocated the benefits of sleep gardens for hospital patients, while Roman military hospitals integrated gardens into expansive spaces to facilitate patient recovery [2]. In Babylonian times, people observed the connection between celestial changes and diseases, recognizing the vital importance of the triad of sky, earth, and water to human health. In the 4th century BC, Hippocrates highlighted the therapeutic efficacy of sea and saltwater [3].

During medieval Europe, monasteries and hospitals were dedicated to providing care for the poor, sick, and physically weak. Typically, they established cloistered courtyard gardens, cultivating medicinal herbs, where herbs and prayers were perceived as the primary forces for restoration and healing [4]. Towards the end of the medieval period, the role of religion in connecting gardens and therapy diminished, making way for more humanistic remedies [5]. Some progressive mental hospitals began emphasizing the relationship between the mind and nature, encouraging patients to engage in plant cultivation.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, European Healing gardens experienced a revival and development, primarily influenced by the Roman social democratic movement and new medical ideologies [2]. At the turn of the 20th century, psychiatric hospitals underwent transformations in treatment and hospital design. Psychological attention replaced physical punishment as the core of therapy, and innovative asylums created evocative landscapes through the design of surrounding spaces and plants for the benefit of the therapeutic experience [6].

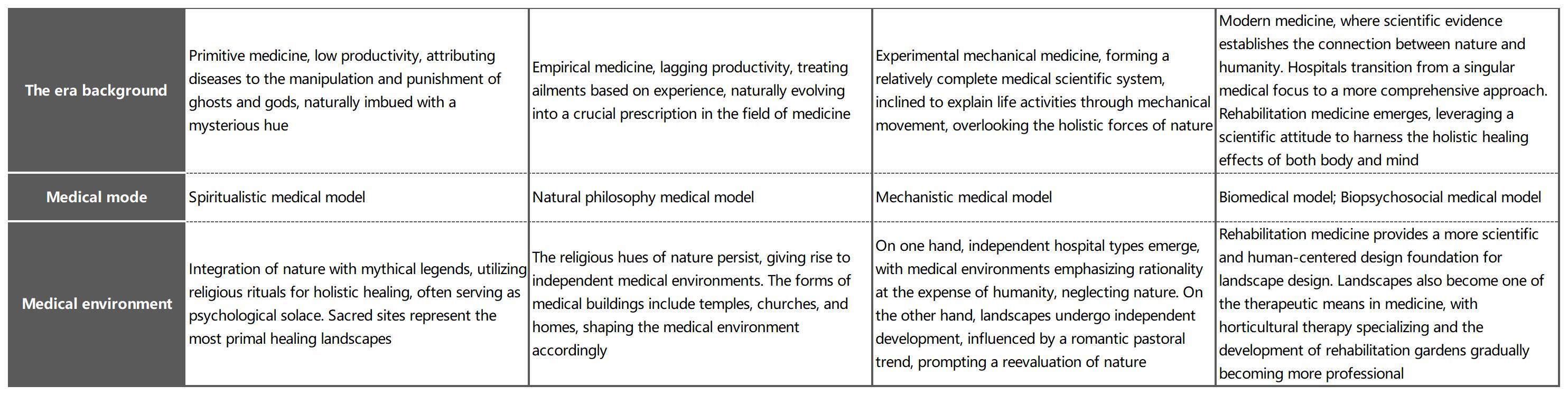

From the mid-20th century onward, the rise of rehabilitation and health medicine shifted the medical focus from diseases to health. This shift in medical paradigm propelled the development of Healing gardens, and from the 1970s, these gardens gradually gained popularity in Western countries [7].

Table 1: Diagram Illustrating the Relationship between Historical Background, Medical Models, and Healthcare Environments [8]

2. Current Research Status of Healing Gardens at Home and Abroad

2.1. Research Status of Healing Gardens Abroad

2.1.1. Healing Garden Design Theories

The foundational figure in modern Healing Garden theory, Roger Ulrich, proposed the theory of natural benefits in the 1970s. Building upon this, Gräslerr introduced the concept of therapeutic landscapes, while Claire Cooper Marcus, an American landscape designer, surveyed over 100 Western medical gardens and formulated design principles for therapeutic landscapes. These principles encompass proximity, affinity, tranquility, comfort, and the incorporation of meaningful artistic effects [9]. In 1973, FROMM [10] introduced the Biophilia hypothesis, emphasizing the innate emotional connection between humans and nature, highlighting the profound benefits derived from contact with the natural environment. Kaplan [11], in the Attention Restoration Theory (ART), explained that prolonged use of directed attention leads to fatigue and reduced work efficiency. ULRICH et al. [12] utilized the Stress Reduction Theory (SRT) to elucidate the emotional and physiological feedback induced by nature. The concept of immersion, initially proposed by Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi, refers to a state of temporary self-forgetfulness and an “immersive experience” when concentrating on a task. The six key elements triggering immersion include clear motivational goals, balance between skills and challenges, a relaxed experiential environment, complete activity control, and timely continuous feedback [13].

2.1.2. Implementation of Healing Gardens

Translating theories into practice is a crucial step in the implementation of specific projects. Outstanding examples of Healing gardens include the Joel Schnaper Memorial Garden and the Elizabeth and Nona Evans Healing Garden in the United States, providing valuable experiential insights for the design of therapeutic landscapes [14]. The Play Garden within the Rusk Rehabilitation Medical Research Institute in New York aims to serve children with brain injuries or ADHD. Designed by Johnson based on recommended child-friendly activities suggested by hospital staff and incorporating the team’s ideas, the garden cleverly addresses micro-topography and landforms, providing adventurous spaces for children’s activities and drawing them into the garden space subconsciously [15]. These successfully implemented projects lay the foundation for the future development of Healing gardens.

In summary, research on Healing gardens abroad began earlier, and compared to China, Western countries have a more mature development of therapeutic landscapes with richer practical experiences. Western Healing gardens are built upon a highly specialized Western medical foundation, with more detailed branches and greater comprehensiveness, primarily serving sub-healthy populations and patients through personalized services. However, Western Healing gardens are based on the national conditions of Western countries and cannot fully meet the needs of domestic healing landscapes. Moreover, their rehabilitation theories are not perfect and require further research and development.

2.2. Current Research Status of Healing Gardens in China

2.2.1. Theoretical Research

Relevant Books: Hospital Healing Garden and Landscape Design, edited by Liang Yongji and Wang Lianqing, provides an on-site analysis of several hospitals in Tianjin. From a landscaping perspective with plants as a focal point, the book introduces the layout, planting, and composition of hospital green spaces [7]. The World of Horticultural Therapy and Therapeutic Landscapes and Horticultural Therapy, edited by Guo Tongren, offer detailed insights into horticultural therapy and landscape therapy [7]. Entering the World of Horticultural Therapy, written by Taiwanese horticultural therapist Huang Shenglou, compiles her study notes during a visit to the United States [7]. Jiang Ziyi provides a comprehensive exposition of Healing gardens, covering aspects such as definition, developmental history, design theory, and the impact on physical and mental health. She emphasizes the importance of cognitive preferences in constructing Healing gardens for the first time [7].

Relevant Journal Papers: The “Yin Yang Five Elements” principle has been applied to the design of eco-friendly healthcare gardens. Cheng Xuke successfully verified the health-promoting function of artificial plants and suggested the potential promotion of this theory within residential areas. In 2009, Yang Huan, Liu Binyi, and others indicated that traditional Chinese medicine in China can guide the landscape design of Healing gardens. Using Healing Garden practice as a case study, the authors elaborated on the relationship between traditional Chinese medicine and Healing Garden theory, proposing Healing Garden design principles based on traditional Chinese medicine health theories [7].

2.2.2. Case Studies

In the residential communities of Lujiazui in Shanghai, based on the Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) “Five Elements” theory, different vegetation corresponding to the health functions of human organs is planted in areas and orientations representing “Metal, Wood, Water, Fire, and Earth” [16].

The Urban Management Bureau of Shenzhen organized research on the analysis of volatile substances and health effects of Lingnan plants, aiming to select plants with health benefits for the construction of Healing gardens (Ye Gensheng, 2011).

Niu Zehui and Xu Feng (2007) applied knowledge related to health sciences and, by combining landscape elements with health-oriented purposes and fostering health awareness, designed a garden in the Lanqiao Waterfront Garden Villas on Jingchang Island. This case is considered quite successful by the authors.

3. Chinese Garden Wellness Philosophy and Its Theories

3.1. What is “Kangyang”?

The term “Kangyang” is a new concept introduced in the context of Chinese culture. The concept of “Kangyang” was proposed by Li Houqiang and others in 2015. “Kang” refers to health, well-being, joy, and recovery, while “Yang” refers to nourishing life, nurturing the spirit, convalescence, and self-cultivation. “Kangyang” is a comprehensive concept that includes both “health” and “nourishment of the body” [17]. In the earliest related journal paper, Zhang Yanlong and others (2019) suggested that “Kangyang” can be interpreted as focusing on ‘nourishment’ with ‘health’ as the goal, emphasizing the process of maintaining and preserving physical and mental health [18]. In the earliest thesis on “Kangyang,” Yang Fei (2019) stated that “Kangyang” encompasses both rehabilitation and convalescence, as well as health and life cultivation [19]. In recent academic theses, Li Xuefei, within the Chinese context, divided the term “Kangyang” into four dimensions: health cultivation, physical health, mental health, and social health, emphasizing their interdependence and integration [20].

3.2. Definition of Garden Wellness (Yuanlin Kangyang)

In 2018, the research team led by Li Shuhua at Tsinghua University [21] proposed the concept of “Yuanlin Kangyang” or Garden Wellness, defining it as different-scale landscape gardens, such as gardens, urban and rural green spaces, scenic areas, wilderness, etc., primarily featuring natural elements. Through spatial experiences, it produces healing and health-promoting effects on the human body in physiological, psychological, spiritual, and social aspects. Specific types include garden therapy, pastoral therapy, forest wellness, green therapy, wilderness therapy, natural therapy, and ecological therapy. Building upon this, Li Shuhua and Kang Ning revised the definition of Garden Wellness to focus on natural elements, particularly garden plants, and different-scale landscape gardens, such as gardens, urban and rural green spaces, scenic areas, and wilderness. Through sensory stimulation, horticultural activities, and spatial experiences, it produces healing and health-promoting effects on the human body in physiological, psychological, spiritual, and social aspects. Specific types include plant wellness, garden healing, pastoral healing, green wellness, wilderness wellness, natural wellness, environmental wellness, and ecological wellness.

3.3. Health and Wellness Philosophy in Classical Chinese Gardens

3.3.1. Health and Wellness Philosophy in Chinese Philosophy

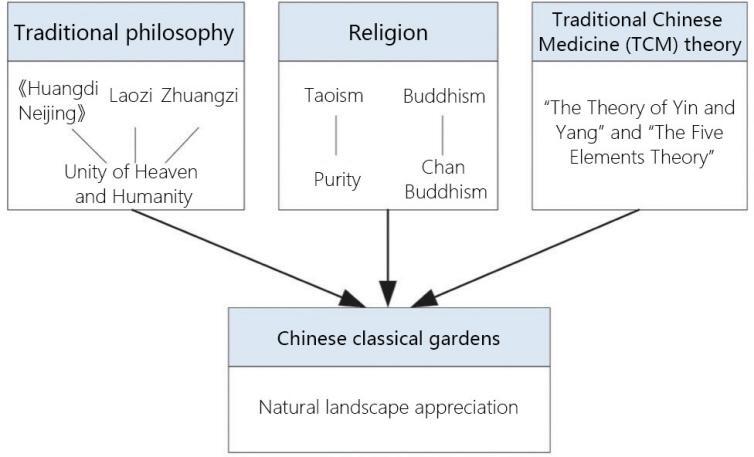

The major schools of thought in traditional Chinese philosophy—Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism—have significantly influenced and permeated various aspects of Chinese politics, economy, culture, and art throughout its extensive history, forming distinct philosophical perspectives on nature [22]. While maintaining their core ideologies, these three schools have interacted, absorbed, merged, and collided, leading to the development of traditional garden design concepts under the influence of traditional philosophical thoughts. This includes Laozi’s “Man follows the Earth, Earth follows Heaven, Heaven follows the Tao, and the Tao follows Nature,” reflecting Laozi’s advocacy for the Tao and reverence for nature. Additionally, Zhuangzi emphasizes harmony with nature, Taoist notions of self-cultivation through internal practices, and the integration of Buddhism with traditional landscape aesthetics. Monks often use natural elements such as mountains, water, flowers, and trees to evoke a meditative environment and enlighten the mind. In summary, the health and wellness philosophy in Chinese philosophy mainly involves three aspects: the idea of “Harmony between Heaven and Humanity,” Feng Shui principles, and the concept of reclusion.

Table 2: Origin and Development of Health and Wellness Philosophy in Classical Chinese Gardens [23]

The concept of “harmony between heaven and man.” In China, the ancient philosophy of “harmony between heaven and man” has been emphasized for centuries. Over two thousand years ago, the “Huangdi Neijing” explicitly stated the unity of humans and nature, asserting that human survival and health are inseparable from the natural environment. It reflects the idea that “heaven and earth are born together with me, and all things are one with me.” It believes that humans should not go against the universal laws of nature and advocates the harmony between heaven and man [23]. Feng Shui theory regards the unity of heaven, earth, and man as the highest principle in Chinese Feng Shui. By observing the sky, examining the earth, choosing auspicious locations, and avoiding inauspicious ones, it seeks the optimal environment for human habitation [23]. Additionally, Feng Shui theory has, to some extent, assisted the philosophy of seclusion. The concept of seclusion was often reflected in ancient Chinese literati, embodying their ideals and aspirations through the belief in “living quietly in the wild, semi-seclusion in the market, and complete seclusion in the court.” [23] For instance, Bai Juyi explicitly introduced the concept of semi-seclusion in his poem “Zhongyin.” Different from complete seclusion in the court or living quietly in the mountains, semi-seclusion involves withdrawing within the city, allowing literati to “avoid mental and physical exertion, and be free from hunger and cold.” This aligns well with the mentality of the literati. “Zhongyin” carries the flavor of Confucian moderation and the Zen principle of “non-attachment to practice.” During the Northern Song Dynasty, when Su Shunqin faced demotion in Bianjing (present-day Kaifeng) and later, after being dismissed, built the Canglang Pavilion during his exile in Wu, and Shi Zhengzhi, after being impeached and removed from office, retreated to the Wangshi Garden in Suzhou that he had built. These literati established their own “utopia” amidst the mundane world, seeking solace through withdrawal from society [22].

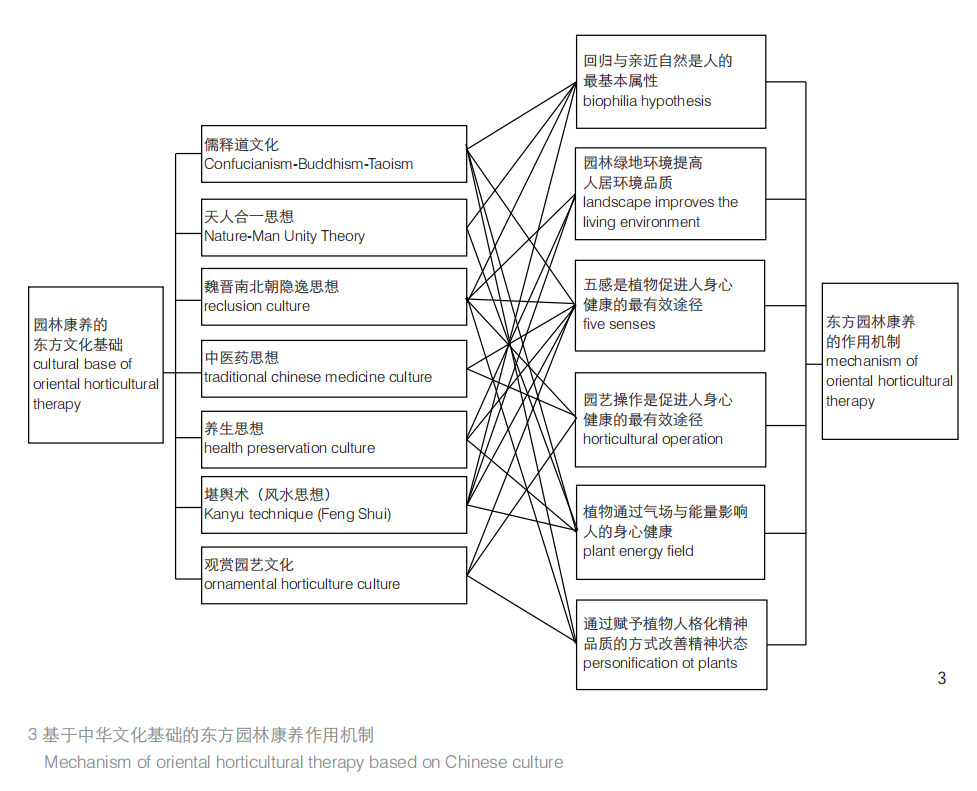

Table 3: Mechanisms of Oriental Garden Wellness Based on Chinese Cultural Foundation [24]

3.3.2. Health and Wellness Philosophy in Garden Space Creation

(I) Site Selection

The essence of garden creation lies in exploring the relationship between humans and nature. In “Yuan Ye·Xiang Di·Cheng Shi Di”, it is mentioned, “A common market cannot be a garden; if it is like a garden, it must be built in a secluded place, so that even though it is close to the common, the gate is closed without noise.” “Xiang Di,” also known as “Zé Jū” (“Choosing Residence”), “Bu Zhái” (“Divination for Residence”), or “Bu Jū” (“Divination for Dwelling”), reflects the stringent requirements of ancient scholars for the site selection of gardens. Ancient thinkers had different views on site selection, as reflected in Confucius’s “Ju Li Ren,” Laozi’s “Ju Shan Di,” and the descriptions in the “Inner Canon” and “Lüshi Chunqiu,” all highlighting the relationship between the natural environment, ecological surroundings, and health. This indicates that ancient people were aware of the close connection between health and the environment at that time.

Regarding the relationship between garden residences and their surrounding environment, “If the overall shape is not good, but the internal form is proper, it will not be completely auspicious. Therefore, the external form of the residence is paramount.” Traditional garden site selection generally emphasizes proximity to mountains and waters, with the garden backed by hills and surrounded on the sides, providing a psychological sense of security. If there are no mountains, alternatives like creating artificial hills using stacked rocks can be considered. A spacious main hall and aesthetically pleasing views are considered auspicious, providing a sense of openness and a rich aesthetic experience. If there are no scenic views within the garden, external scenery can be incorporated. The role of flowing water in improving psychological health has been verified by scholars. A residence surrounded by flowing water with gentle curves is considered favorable, and the sound of water should be pleasant. Ancient wisdom also acknowledges the virtue of water, stating, “The highest goodness is like water,” illustrating how flowing and clear water can provoke deep thoughts, purify the mind, and elevate the spirit [20]. Integrating natural scenery into the garden, adhering to the Feng Shui pattern of being near mountains and water, and combining the human body, thoughts, and environment is precisely what garden wellness seeks to achieve—a realm where “every landscape is a language of emotions” [20].

(II) Spatial Arrangement

Chinese traditional garden layouts almost exclusively adhere to a sequence of “starting point—rhythm—climax—finale,” seeking to uplift through restraint. This approach shares subtle connections with the rhythm of classical music [22]. Typically, the spatial arrangement of a garden is directly influenced by the creator’s spirit, giving rise to different themes. There is the “circumambulation-style” layout, exemplified by Canglang Pavilion and Wangshi Garden. This type of layout usually centers around mountain or water scenes, surrounded by winding paths. In contrast to a linear tour, the winding paths significantly extend the duration of the visit while achieving a shared mental and physical experience of multiple views.

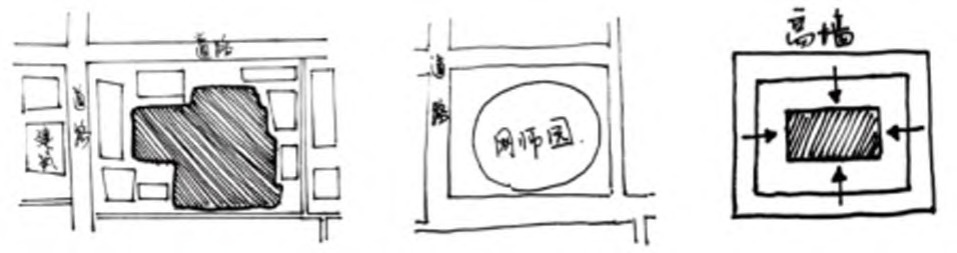

Figure 1: Overview of Canglang Pavilion [22]

Figure 2: Overview of Wangshi Garden [22]

Many other traditional gardens also exhibit unique health-oriented characteristics in their spatial arrangements. For instance, Chengde Mountain Resort employs a “circular concentric” layout symbolizing imperial authority, the Lion Grove features a religiously infused “ascending to heaven step by step” layout, and the grand “musical composition structure” layout of the Zhuozheng Garden also reflects similar health-promoting environmental features [22].

(III) Functional Space

Gardens were crucial spaces in the lives of ancient people, serving as places for daily activities, artistic pursuits like music, chess, calligraphy, and painting, as well as a means to connect with nature. The interconnection and layout of different functional areas in gardens reflected traditional philosophical thoughts and the garden owner’s intentions, making it a latent core in creating a wellness atmosphere and a healthy environment. As mentioned in the “Huangdi Zhaijing” (The Yellow Emperor’s Book of Residences), “Every person resides in a dwelling, regardless of its size. Though the dimensions may vary, the distinction between yin and yang is present. Even when temporarily dwelling in a single room, there are fortunes and misfortunes. For larger residences, there are extensive discussions, while smaller ones receive more concise considerations. Violations may bring disasters, but rectifying them can avert harm, akin to the effectiveness of treating an ailment.” In essence, the Feng Shui of a residence is directly linked to human health. Favorable Feng Shui in a residence can be likened to having therapeutic effects on one’s well-being. “Connecting to dense woods, with flowers and trees in abundance” [20], indicates that a residence should be situated near lush woods and flourishing flowers and trees.

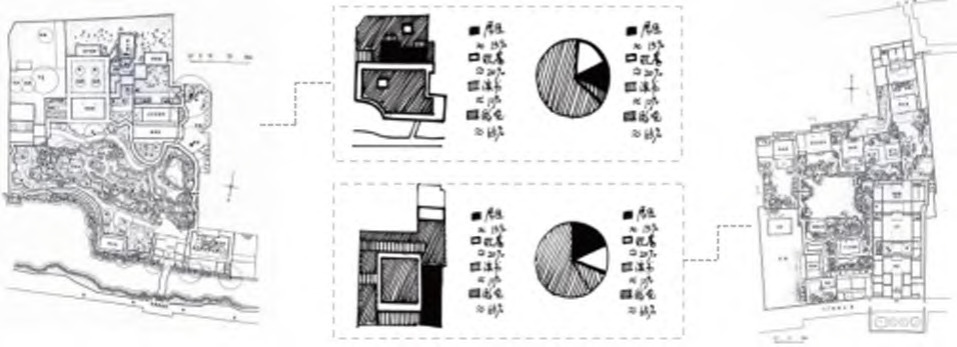

Taking the examples of Wangshi Garden and Canglang Pavilion, the residential spaces in these gardens are often appropriately separated from surrounding functional spaces to create a tranquil living environment. Reading spaces act as a transition between residential and external spaces, offering a relatively enclosed area for quiet study and contemplation. Touring spaces are distributed in a plane or linear fashion, promoting physical well-being. Landscape spaces are primarily arranged in a point-like manner, situated at the center or periphery of touring spaces, showcasing the overall beauty of the garden while allowing detailed appreciation of its intricate features. Therefore, a livable therapeutic garden needs to maintain a connection and balance in the proportion, distribution, and detailed arrangement of functional spaces. Through reasonable functional ratios and layouts, it is possible to create therapeutic spaces that are suitable for different needs - living, exploring, and strolling.

Figure 3: Functional Distribution of Canglang Pavilion and Wangshi Garden [22]

Figure 4: Techniques of Meandering Paths and Spatial Orientation in Gardens [22]

3.3.3. “Kangyang” Concepts in the Construction of Garden Landscapes

When discussing “Kangyang”, it is inevitable to address the five senses: vision, hearing, smell, touch, and taste. These senses significantly impact physical health, with vision, hearing, and smell being the most prominent. Classical Chinese gardens are known for their charming ability to engage multiple dimensions of human senses. Designs such as the fragrance of orchids, the sound of birds, and observing a waterfall in the rain all emphasize the connection and interaction between the five senses. To create a richer aesthetic experience, in the immersive garden tours, visual, auditory, and olfactory stimuli tend to complement each other, collaboratively crafting a multi-layered sensory enjoyment. While Western research on therapeutic gardens has been at the forefront, within China’s extensive history of 5,000 years of civilization, theories related to health and well-being have consistently held significant importance. The Daoist theories of health preservation and the traditional Chinese medicine’s Yin-Yang and Five Elements doctrines extensively explore the close relationship between human health and the natural environment. Scholars such as Zhang Jinli have conducted research on the landscape space division and plant landscape construction based on the theory of operations research and health preservation. In the implementation of designing gardens for treating liver qi stagnation and excessive liver fire, the ingenious application of the yin-yang and five elements theory in landscape design has achieved positive health-preserving effects.

Landscape creation involves more than just visual elements; soundscapes are also an integral part. This includes sounds of water, wind, living organisms, and artificial sounds. For instance, in Suzhou’s Zhuozheng Garden, there is a structure named “Listening to Rain Pavilion,” embodying the poetic sentiment of “listening to the sound of rain hitting banana leaves.” The same sound of rain hitting banana leaves can evoke different emotional responses based on the listener’s state of mind. Locations like Canglang Pavilion’s “Verdant Delicate Hall,” Zhuozheng Garden’s “Listening to the Wind Spot,” and Yangzhouge Garden’s “Breeze-Permeated Moon-Viewing Hall” are places to appreciate the sounds of wind. Combining the sounds of birds, cicadas, and flowing water with the natural landscape creates a therapeutic auditory experience that brings joy and relaxation. Additionally, aromatic landscapes in gardens are typically created using fragrant plants. For example, in Suzhou, the “Little Mountain with Cassia Trees Pavilion” south of the Wangshi Garden combines rocks, artificial hills, and various flowering plants to construct a secluded yet ethereal space. During the blooming season, the interaction between floral scents and the garden landscape stimulates imaginative thoughts. The “Fragrance of Osmanthus Pavilion” in Liuyuan Garden is another exemplary instance, allowing individuals to linger in the scent of osmanthus flowers and immerse themselves in the natural scenery. These examples highlight the significance of auditory and olfactory elements in gardens, providing people with joy and enjoyment.

In addition to objectively improving human health by releasing negative ions, fixing carbon dioxide, releasing oxygen, reducing airborne particulate matter, sterilizing, and reducing noise, plants in gardens can also express the passage of time through therapeutic landscape plants. Various plants undergo corresponding changes in different seasons. Planting different types of vegetation in the same area allows people to experience the seasonal changes in plant landscapes at the same location. Furthermore, therapeutic landscape plants are used to express space and create scenic spots. Plants play a crucial role in creating therapeutic landscapes, as their distinctive features provide diverse sensory experiences. The aesthetic beauty of individual plants can be showcased through independent planting, or their harmonious combinations can be depicted through structural diagrams to illustrate the overall landscape’s aesthetic appeal [25].

3.3.4. Health and Wellness Concepts in Courtyard Activities

The “Vacancy and Tranquility” theory is at the core of traditional Chinese health preservation studies. However, excessive “vacancy” and “tranquility” throughout the day can be detrimental to health. Therefore, enlightened philosophers and physicians from ancient times proposed a necessary theoretical complement, emphasizing the concepts of “exertion” and “activity,” namely, the “exertion of the body” theory. In “Su Wen: Discussion on Regulating the Spirit with the Four Seasons,” different “body-exerting” health preservation methods are recommended for various seasons. For instance, in spring, it is advisable to “sleep early and rise early, take a broad walk in the courtyard”; in summer, “sleep early and rise early, do not tire of the sunlight”; in autumn, “sleep early and rise early, rise simultaneously with the rooster”; and in winter, “sleep early and rise late, waiting for the daylight.” Additionally, there is a health preservation principle of “nurturing yang in spring and summer, nurturing yin in autumn and winter.” These methods actively enhance the body’s adaptability to cope with changes in the natural environment.

During the Qing Dynasty, health preservationist Cao Tingdong, in “Constant Advice for the Elderly,” advocated planting flowers and trees, raising fish, and arranging flowers in the courtyard. He emphasized the importance of ensuring continuous blossoming of flowers throughout all four seasons. Cao also highlighted personal involvement in these activities, such as watering, raising goldfish, and flower arranging. This not only beautified the living environment but also physically exercised the body.

(I) Gardening

Various activities in courtyard living not only contribute to physical fitness and flexibility but also cultivate one’s temperament, integrating aesthetics into the garden environment [25]. Ancient individuals, while planting medicinal herbs, fruits, and flowers, appreciated the forms of plants, nurtured the life of flowers and plants, and through the life of plants, influenced their own lives, embodying the theme of harmonizing with life. For example, during the Northern Song Dynasty, Sima Guang described the landscapes of a medicinal herb garden and a flower-watering pavilion in “Records of the Dule Garden,” combining the cultivation of medicinal herbs, herbs, and peonies with relaxation. During the Ming Dynasty, Yuan Zongdao built a small garden named “Embracing the Jar Pavilion” in the inner city of Beijing, where he planted melons, fruits, and vegetables. He assigned someone to water them daily, creating a rural scene within the city. Ming Dynasty health preservationist Gao Miao mentioned in “Ling Sheng Ba Zhi” that after breakfast, one could engage in various gardening activities, such as planting vegetables and flowers, to enjoy the freshness. The Qing Dynasty literati Yuan Mei also regulated his mood and promoted health through flower appreciation and cultivation.

(II) Raising Geese and Fish

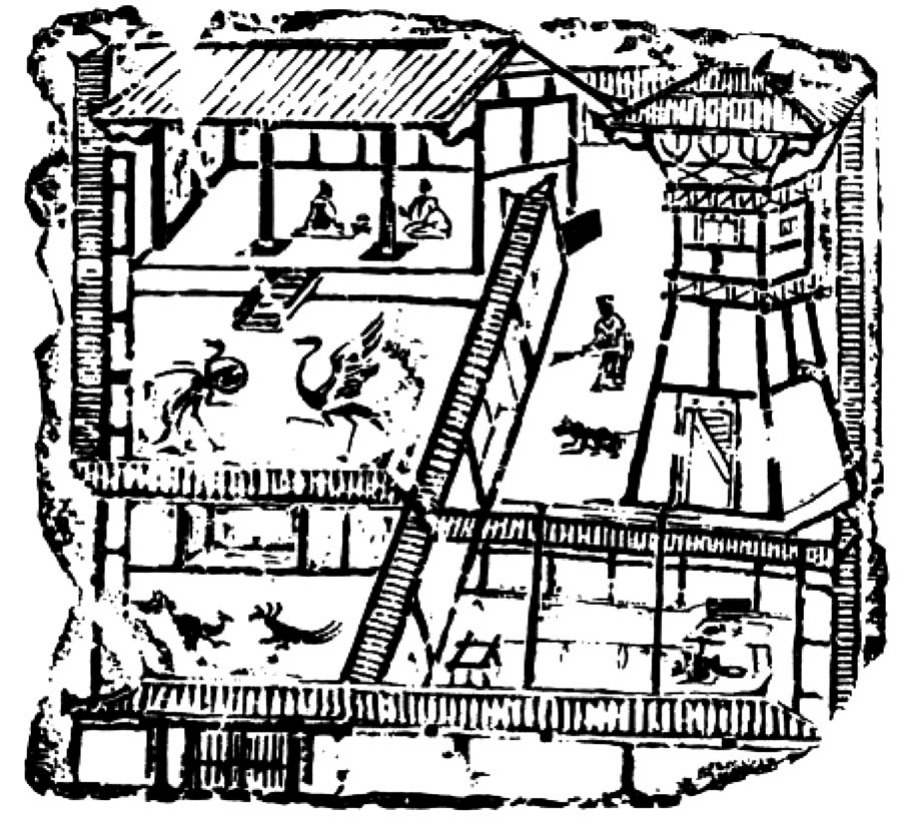

Raising geese and fish in the garden is not just a way for homeowners to participate in activities such as feeding and interacting but also provides sufficient physical contact and pleasure for the body and mind. In private gardens of different periods, residential spaces dedicated to raising geese and fish have emerged. Scenes of interaction between geese and humans are depicted on handed-down pictorial bricks and pictorial stones.

In “Records of Long Things: Foxes and Fish,” it is mentioned, “Regulating the heart and temperament, taming birds, and playing with fish are essential economic activities for living in seclusion in the mountains.” This means that while living in seclusion in the mountains, economic benefits can be achieved through activities such as regulating the heart and temperament, taming birds, and playing with fish.

The “Lively Slope” in the Liuyuan Water Pavilion is inspired by the poem “Self” by Yin Mai, which states, “Beyond the window, birds and fish are lively.” Surrounding the water pavilion, there are birds perching on trees and fish leaping in the creek, creating a lively natural landscape. Illustrations of Lin Hejing releasing cranes are carved on the short windows on either side of the water pavilion. From the practical construction of the landscape to the imaginative creation in paintings, Liuyuan showcases the enriching and therapeutic concepts associated with raising geese [20].

Figure 5: Eastern Han Dynasty Brick Painting - “Courtyard” with Birds

Figure 6: Eastern Han Dynasty Brick Painting - “Fishing Scene” [20]

(III) Strolling

Strolling is an activity characterized by autonomy, walking, and intermittent pauses, and the stroller should maintain a leisurely and relaxed state. Water, if not turbid, will be clear; if stagnant and not flowing, it cannot maintain clarity. This is a method for nurturing the soul, as strolling is intended for soul maintenance. Walking in the garden can alleviate physical stiffness and relieve melancholic emotions. The “Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon: Declaration of the Five Sections” mentions, “Long-time harm to the eyes impairs blood, long-time lying down harms blood, long-time sitting harms muscles, long-time standing harms tendons and bones, long-time walking harms tendons and collaterals. These are the five kinds of harm to the body caused by exhaustion.” Regular walks in the garden, combining labor and rest, can prevent harm to the body from these five types of exhaustion. For ancients, the importance of strolling for health preservation was self-evident. Those adept at health preservation habitually strolled in the garden in the morning after waking up, after meals, and before bedtime, promoting physical well-being.

Chinese classical private gardens, in their landscape designs, pay attention to dynamic layout changes and points of interest, known as “shifting scenes.” Moreover, the rich topographical variations allow individuals to experience endless vitality and unlimited interest during walks, continuously generating interest and enjoying it tirelessly, thereby exercising the body.

4. Conclusion and Outlook

Chinese classical garden culture emphasizes the harmonious coexistence of humans and nature, focusing on creating comfortable and pleasant living spaces. It integrates art, philosophy, and a natural perspective, pursuing mental tranquility and peace. Through the layout of garden landscapes, plant selection, and spatial design, classical gardens create a rational living environment, providing both spiritual and physical wellness experiences. In comparison to Healing gardens serving specific groups, the service scope of wellness garden landscapes is more extensive, not only addressing the health recovery of specific populations but also emphasizing the general population’s health maintenance.

Facing various health issues today, the construction of green spaces in wellness-oriented residential areas presents both opportunities and challenges for the landscape and gardening industry. In this context, we can reflect on the long history of Chinese classical private garden culture, providing valuable references for solving contemporary issues. Chinese classical private garden culture possesses abundant wellness elements, offering a solid foundation and a rich treasure trove for constructing healthy living environments. In the process of building wellness-oriented residential areas, the principles and experiences of classical private gardens can be drawn upon. By creating green spaces, landscapes, and public areas, a harmonious environment between humans and nature can be cultivated. Emphasis on plant selection, landscape planning, and spatial layout makes residential areas places for people to relax and enjoy nature. Simultaneously, through the integration of cultural connotations, residents are encouraged to love and engage with traditional culture, enhancing the overall cultural atmosphere of the community.

In summary, Chinese classical private garden culture serves as an essential basis and valuable resource for constructing healthy living environments. By borrowing the experiences and wisdom of classical gardens, we can build modern residential areas that combine aesthetic value and wellness functionality, creating a livable and healthy living environment for people.

References

[1]. Liu, J. H. (1999). Horticultural therapy. Greening and Living, (01), 9.

[2]. Patrick Francis Muñoz. (2009). World development of healing landscapes. Chen, J. Y., Trans. China Garden, (8), 24-27.

[3]. Qi, D. W. (2007). Achieving physical and mental balance: A preliminary exploration of the landscape design of rehabilitation and recuperation spaces (Unpublished master’s thesis). Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China.

[4]. Claire Cooper Marcus & Barnes. (2007). Healing Gardens: Theory and Practice. Jiang, Z. Y., Wu, Z. Z., & Lin, F. L., Trans. Taipei: Taiwan Wunan Publishing, 2-20.

[5]. Tyson, M. M. (2008). The healing landscape: Therapeutic outdoor environment. Madison, WI: Parallel Press, 4-12.

[6]. Claire Cooper Marcus & Barnes. (2007). Healing Gardens: Theory and Practice. Jiang, Z. Y., Wu, Z. Z., & Lin, F. L., Trans. Taipei: Taiwan Wunan Publishing, 2-20.

[7]. Lei, Y. H., Jin, H. X., & Wang, J. Y. (2011). Research status and prospects of Healing gardens. China Garden, 27(04), 31-36.

[8]. Qi, D. W. (2007). Achieving physical and mental balance: A preliminary exploration of the landscape design of rehabilitation and recuperation spaces (Unpublished master’s thesis). Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China.

[9]. Li, Q., & Tang, X. M. (2012). Construction of a quality evaluation index system for Healing gardens. Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University: Agricultural Science Edition, 30(3), 58-64.

[10]. Fromm, E. (1973). The anatomy of human destructiveness. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

[11]. Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 169-182.

[12]. Ulrich, R. S., Simons, R. F., Losito, B. D., et al. (1991). Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 11(3), 201-230.

[13]. Qi, Y., Zhang, X. X., Feng, J. R., Xiang, Y. Y., & Hu, J. P. (2020). Research on the environmental creation of autism healing centers in China. Journal of Suihua University, 40(01), 84-87.

[14]. Shen, Z. X. (2013). Research on the construction of rehabilitative gardens in small public spaces in China (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Chinese Academy of Forestry, China.

[15]. Claire Cooper Marcus, Luo Hua, & Jin Hexian. (2009). Healing Gardens. China Garden, 25(07), 1-6.

[16]. Huang, B. B., & Cui, R. F. (2011). Research on the theory and practice of health-oriented garden design. Modern Agricultural Science and Technology, (22), 247-249+257.

[17]. Li, H. Q., Liao, Z. J., Lan, D. X., et al. (2015). Ecological rehabilitation theory. Chengdu: Sichuan People’s Publishing House.

[18]. Zhang, Y. L., Niu, L. X., Zhang, B. T., et al. (2019). Healing landscape and garden plants. Garden, 2019(02), 2-7.

[19]. Yang, F. (2019). Research on the landscape planning and design of health industry parks under the “health + “ model (Unpublished master’s thesis). Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot, China.

[20]. Li, X. F., & Li, S. H. (2021). Research on health preservation ideas in the construction of classical private gardens in China. Residential Area, 2021(01), 124-131.

[21]. Li, S. H. (2020). Green health preservation. Journal of Northwest University (Natural Science Edition), 50(06), 851.

[22]. Chen, X. X., Lu, Y. J., Yang, M. J., Yu, R. Z., & Wang, Y. (2023). Research on the relationship between traditional Chinese garden health preservation ideas and modern healthy living environments. Modern Horticulture, 46(05), 118-121. DOI: 10.14051/j.cnki.xdyy.2023.05.016.

[23]. Zhang, L. (2021). Comparative study of the theory of healing environment and the health preservation ideas of classical Chinese gardens. China Famous City, 35(03), 46-51. DOI: 10.19924/j.cnki.1674-4144.2021.03.007.

[24]. Li, S. H., & Kang, N. (2023). Building a professional system for Chinese garden health preservation. Landscape Architecture, 30(03), 81-87.

[25]. Zhang, Y. L., Niu, L. X., Zhang, B. T., Guo, L. N., Zhao, R. L., & Yan, Z. G. (2019). Healing landscape and garden plants. Garden, 2019(02), 2-7.

Cite this article

Liu,L. (2024). Healing Gardens from the Perspective of Oriental Gardens – Therapeutic Landscapes. Advances in Humanities Research,4,92-104.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Humanities Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Liu, J. H. (1999). Horticultural therapy. Greening and Living, (01), 9.

[2]. Patrick Francis Muñoz. (2009). World development of healing landscapes. Chen, J. Y., Trans. China Garden, (8), 24-27.

[3]. Qi, D. W. (2007). Achieving physical and mental balance: A preliminary exploration of the landscape design of rehabilitation and recuperation spaces (Unpublished master’s thesis). Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China.

[4]. Claire Cooper Marcus & Barnes. (2007). Healing Gardens: Theory and Practice. Jiang, Z. Y., Wu, Z. Z., & Lin, F. L., Trans. Taipei: Taiwan Wunan Publishing, 2-20.

[5]. Tyson, M. M. (2008). The healing landscape: Therapeutic outdoor environment. Madison, WI: Parallel Press, 4-12.

[6]. Claire Cooper Marcus & Barnes. (2007). Healing Gardens: Theory and Practice. Jiang, Z. Y., Wu, Z. Z., & Lin, F. L., Trans. Taipei: Taiwan Wunan Publishing, 2-20.

[7]. Lei, Y. H., Jin, H. X., & Wang, J. Y. (2011). Research status and prospects of Healing gardens. China Garden, 27(04), 31-36.

[8]. Qi, D. W. (2007). Achieving physical and mental balance: A preliminary exploration of the landscape design of rehabilitation and recuperation spaces (Unpublished master’s thesis). Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China.

[9]. Li, Q., & Tang, X. M. (2012). Construction of a quality evaluation index system for Healing gardens. Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University: Agricultural Science Edition, 30(3), 58-64.

[10]. Fromm, E. (1973). The anatomy of human destructiveness. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

[11]. Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 169-182.

[12]. Ulrich, R. S., Simons, R. F., Losito, B. D., et al. (1991). Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 11(3), 201-230.

[13]. Qi, Y., Zhang, X. X., Feng, J. R., Xiang, Y. Y., & Hu, J. P. (2020). Research on the environmental creation of autism healing centers in China. Journal of Suihua University, 40(01), 84-87.

[14]. Shen, Z. X. (2013). Research on the construction of rehabilitative gardens in small public spaces in China (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Chinese Academy of Forestry, China.

[15]. Claire Cooper Marcus, Luo Hua, & Jin Hexian. (2009). Healing Gardens. China Garden, 25(07), 1-6.

[16]. Huang, B. B., & Cui, R. F. (2011). Research on the theory and practice of health-oriented garden design. Modern Agricultural Science and Technology, (22), 247-249+257.

[17]. Li, H. Q., Liao, Z. J., Lan, D. X., et al. (2015). Ecological rehabilitation theory. Chengdu: Sichuan People’s Publishing House.

[18]. Zhang, Y. L., Niu, L. X., Zhang, B. T., et al. (2019). Healing landscape and garden plants. Garden, 2019(02), 2-7.

[19]. Yang, F. (2019). Research on the landscape planning and design of health industry parks under the “health + “ model (Unpublished master’s thesis). Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot, China.

[20]. Li, X. F., & Li, S. H. (2021). Research on health preservation ideas in the construction of classical private gardens in China. Residential Area, 2021(01), 124-131.

[21]. Li, S. H. (2020). Green health preservation. Journal of Northwest University (Natural Science Edition), 50(06), 851.

[22]. Chen, X. X., Lu, Y. J., Yang, M. J., Yu, R. Z., & Wang, Y. (2023). Research on the relationship between traditional Chinese garden health preservation ideas and modern healthy living environments. Modern Horticulture, 46(05), 118-121. DOI: 10.14051/j.cnki.xdyy.2023.05.016.

[23]. Zhang, L. (2021). Comparative study of the theory of healing environment and the health preservation ideas of classical Chinese gardens. China Famous City, 35(03), 46-51. DOI: 10.19924/j.cnki.1674-4144.2021.03.007.

[24]. Li, S. H., & Kang, N. (2023). Building a professional system for Chinese garden health preservation. Landscape Architecture, 30(03), 81-87.

[25]. Zhang, Y. L., Niu, L. X., Zhang, B. T., Guo, L. N., Zhao, R. L., & Yan, Z. G. (2019). Healing landscape and garden plants. Garden, 2019(02), 2-7.