1. The Emergence and Development of the Concept of Ugliness

In the development of Western classical art, beauty and harmony have often been regarded as the highest principles. As early as in ancient Greece, "beauty" was the most revered artistic belief of the time. The pursuit of beauty in ancient Greece reached its peak, to the extent that, according to the works of German philosopher Lessing in "Laocoon", the laws of the city-state of Thebes explicitly stated: artists must imitate things to be more beautiful than the originals, not uglier; violators would be punished . However, the exclusivity created by the singular celebration of beauty also banned its opposite, ugliness, which was deemed impure, filthy, and even sinful.

In the medieval period, aesthetician Augustine built upon previous ideas to propose his unique perspective on the concept of ugliness, namely the relativity of ugliness. He believed that there is no absolute ugliness in the world; ugliness is "merely relative deficiency." Thus, he considered ugliness as a subsidiary element of beauty, a backdrop that highlights beauty by comparison . Beauty and ugliness possess a mutual transformability, where ugliness can be converted and utilized as part of beauty. Although Augustine's views on ugliness are briefly mentioned in his "Confessions", it is evident that, compared to ancient Greece, the concept of ugliness began to receive attention.

It was not until the eighteenth century that German aesthetician Baumgarten established aesthetics as a separate discipline, marking a breakthrough development. In his definition of aesthetics, he stated: "In the broad sense of the capacity for appreciation, the visible, evident perfection of form is beauty; correspondingly, its opposite is ugliness." It is clear that Baumgarten, while establishing the definition of aesthetics, also explored the question of "what is ugliness", refining the basic definition of ugliness.

Another German aesthetician, Rosenkranz, in his work "Aesthetics of Ugliness", conducted a comprehensive and profound discussion on the meaning of ugliness, allowing ugliness to be judged and evaluated objectively by people. He categorized ugliness into three types: natural ugliness, spiritual ugliness, and artistic ugliness, and defined the characteristics of ugliness (formlessness, non-conformity, distortion, or malformation). "Aesthetics of Ugliness" is the first systematic study of the category of ugliness and incorporates it into the realm of aesthetics, marking the beginning of modern ugliness studies and its epoch-making significance.

At the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century, the outbreak of the two World Wars and the rise of capitalism propelled rapid scientific and technological advancements, but also led to a significant expansion in the wealth gap. Driven by this social backdrop, the turmoil in society and the surge of humanism turned society into an alienated one, inevitably affecting individual development and prompting innate resistance. Thus, under the double shadow, "beauty" was naturally negated, and "ugliness" was highlighted [6]. Of course, the rise of ugliness studies was not solely due to social reasons but also included the alienation of religious beliefs and nature, among other comprehensive factors. In 1857, Baudelaire's poem "Les Fleurs du mal" (The Flowers of Evil), filled with imagery of ugliness, heralded the advent of modern ugliness studies, making ugliness an independent aesthetic category and entering a relatively independent period.

Ugliness began to manifest in many artistic fields in the twentieth century, where the absurd, bizarre, and ugly primarily aimed to depict, denounce, and respond to a series of problems in the Western context of the time. There were two art forms associated with ugliness studies: Expressionism and Naturalism, each with different connotations. Naturalism depicted reality without embellishment, while Expressionism represented the artist's emotions based on the real world, mainly reflecting social turmoil and the fragmented inner emotions of individuals. Adorno, a representative of the Frankfurt School, once said in his "Aesthetic Theory": "Art needs to employ ugliness as a form of negation to realize itself."

Thus, from being despised and excluded in ancient Greek times, to being a backdrop for beauty in the medieval period, to transforming with beauty in the eighteenth century, and finally standing out in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the development and prosperity of ugliness studies cannot be separated from the evolution and changes in history and society, continuing to develop up to the modern era.

2. The Embodiment of Ugliness in 20th Century Music

Prior to the 19th century, classical music strictly adhered to aesthetic principles, with completeness, regularity, and harmony as its main features. However, the extreme suppression of the pre-war social environment and the extreme volatility of the economic environment in the 20th century led to a loss of balance in people's inner worlds and questioning of traditional worldviews and value standards. It was during this time that ugliness studies, as the antithesis of aesthetics, emerged. The influence of ugliness studies is multifaceted, with its characteristics particularly evident in expressionist music.

The West, after undergoing the ordeals of two World Wars from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century, witnessed countless lives lost and economic stagnation. In this context, people had no trust in Western governments and powerful forces, leaving them with nowhere to turn internally. As Nietzsche wrote in "Thus Spoke Zarathustra": "The edifice of human belief has collapsed." Thus, artists of the time, in order to express complex inner emotions and depict and satirize current social realities, centered expressionism around ugliness studies, employing grotesque and absurd techniques to portray and satirize the real world, evident in music, art, and literature. Arnold Schoenberg, a representative figure of 20th-century musical expressionism, abandoned tradition with his invention of the twelve-tone technique , diverging from Romanticism and previous "beauty"-centered musical forms, using new musical techniques to create a form of music that matched the ugliness studies of the 20th century.

Schoenberg broke away from the traditional tonal music form, utilizing discordant chords, irregular dynamics, complex and variable rhythms, unexpected harmonic progressions and terminations, and elusive melodies (rarely reprised) to depict music. This new musical form portrayed the real and ugly objective world, aligning with the concepts of ugliness studies mentioned earlier [2]. Thus, 20th-century expressionist music, hand in hand with ugliness studies, made its brilliant debut, aiming to depict reality and reflect social issues, contributing its strength to exploring the true side of society.

Schoenberg's first work using the twelve-tone technique was born in 1923, and his "Piano Suite" No. 25 consists of six pieces, including "Prelude", "Gavotte", "Musette", "Intermezzo", "Minuet", and "Gigue". This article focuses on the "Prelude" from the Piano Suite as an example to discuss the relationship between expressionist music led by Schoenberg and ugliness studies.

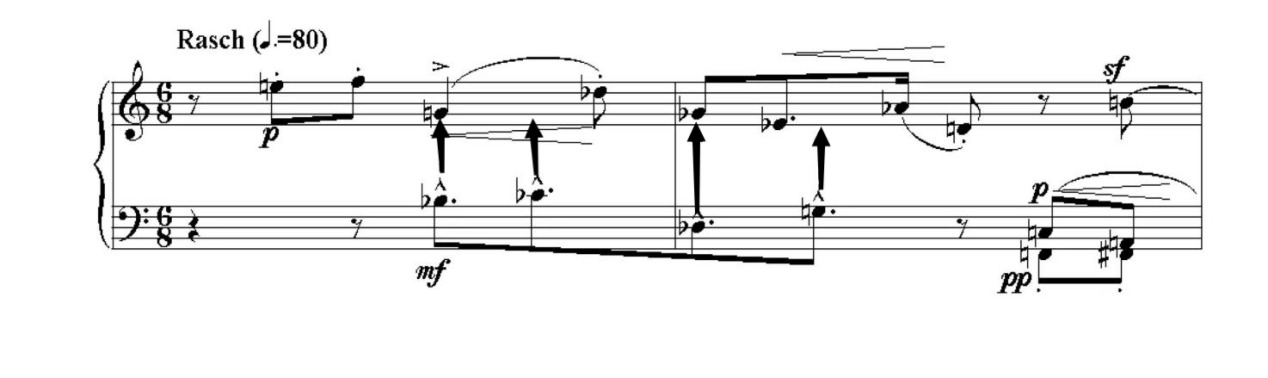

As mentioned earlier, Schoenberg's use of rhythm and meter differed from the traditional, adeptly employing complex rhythms and meters to depict the uniqueness of music. For example, in measures 1-2 of the "Prelude", the left hand plays a relatively tidy rhythm, while the right hand uses a "staggered" rhythmic counterpoint technique to highlight the timbral differences between the voices, emphasizing the contrast in timbre. The two voices in the left and right hands oppose and yet merge with each other, forming a contradictory conflict of beauty, which is closely related to the essence of ugliness studies. Daniel Bell, when discussing the contradictions in capitalist culture, mentioned: "The bankruptcy of religious authority in the mid-19th century led to a psychological shift towards relaxation. As a result, culture—especially modernist culture—took on the task of dealing with the devil. Unlike religion, which seeks to tame the devil, it embraces, explores, and studies it in the guise of secular culture (art and literature), gradually seeing it as a source of creation." Due to the elevation of the subject, the awareness of individuality, the liberation of man, and the socio-historical background of the 20th century, human rational thinking clashed with feudal theology and capitalist thought. The human desire for freedom contradicts the theological repression of human nature, making ugliness inevitably stand out in people's emotional psychology and attract attention. [3]

Example 1: Measure 1-2 of the "Prelude"

For another example, a rhythmic pattern  appears in measure 5 of the "Prelude", which occurs five times throughout the piece. Each occurrence utilizes different pitch materials, timbres, and directions. Moreover, Schoenberg adeptly uses shifts in accentuation to depict changes in musical rhythm, such as the irregular accent markings and the unconventional use of a 3/8 beat plus a 1/8 beat in measure 23. Even when rhythms are specified, Schoenberg often employs special performance markings to bestow the music with new forms of expression. This involves disrupting the original beat and shifting the accents, creating a new auditory effect.

appears in measure 5 of the "Prelude", which occurs five times throughout the piece. Each occurrence utilizes different pitch materials, timbres, and directions. Moreover, Schoenberg adeptly uses shifts in accentuation to depict changes in musical rhythm, such as the irregular accent markings and the unconventional use of a 3/8 beat plus a 1/8 beat in measure 23. Even when rhythms are specified, Schoenberg often employs special performance markings to bestow the music with new forms of expression. This involves disrupting the original beat and shifting the accents, creating a new auditory effect.

Example 2: Measure 23 of the "Prelude"

————Schoenberg's explanation is: "Emphasize like a downbeat."

————Schoenberg's explanation is: "Emphasize like a downbeat."

————Schoenberg's explanation is: "Play like an upbeat, without emphasis."

————Schoenberg's explanation is: "Play like an upbeat, without emphasis."

From these two examples, it is not difficult to see that Schoenberg, by breaking conventions with unusual uses of rhythm and meter, highlighted the absurdity of his musical works, seeking new paths of expression with unique rhythmic forms. With unsettling sound effects as a form of deformed, pathological representation, he depicted ugliness through irrational music, pulling down the traditional rational music (music conforming to the essence of aesthetics) from its pedestal, breaking the complete, harmonious, and universally recognized aesthetic image crafted in the late 18th century and before. What then is the aesthetic significance of this irrational music? As Niu Hongbao mentions in his "Introduction to Aesthetics": "Forcing the irrational will into an irregular, abstract, and dismembered form, on one hand, expresses the unpleasant and terrifying feelings evoked by people's anxiety over economic instability and the pressures of war through fragmented expressionist music. On the other hand, it arouses a sense of power, a stimulating excitement, which is the aesthetic pleasure evoked by the manifestation of irrational consciousness." This precisely matches the characteristics of Schoenberg's music.

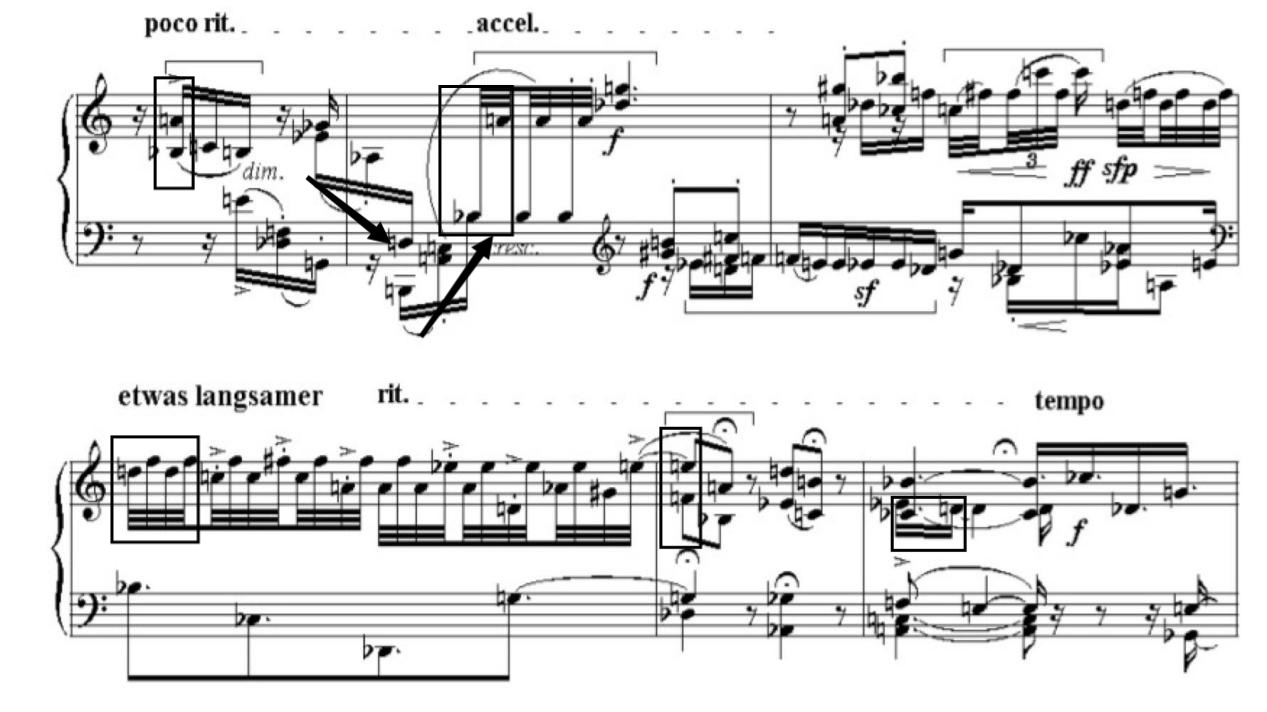

At the same time, Schoenberg often used the dramatic musical depiction by coordinating the melody's contour with the dynamics of rhythm, making the auditory effects of the music even more unpredictable and producing an absurd ugliness effect. This ungraspable, absurd quality of the music pushes the contradictory, discordant, uncertain, and irrational aspects of expressionist music to an irreversible extreme, causing the audience to experience a boundless sense of oppression, absurdity, and disorientation during the listening process. [4]

Example 3: Measures 12-16 of the "Prelude"

In Example 3, measures 12 and 13 feature contrary motion between the left and right hands, complemented by thirty-second notes interspersed in the right hand, the use of triplet notes in measure 14 in the right hand, and the interweaving notes between the two voices in the left hand. The changing note values, from sixteenth notes in measure 12 to thirty-second notes in measures 13 and 14, and then a sudden shift to eighth notes and tie marks in measure 15 to depict the music's tension, returning to sixteenth notes in measure 16. The direction of the music and the use of note values, combined with the three-voice texture, produce an unpredictable auditory effect for the audience. The emotional unpredictability keeps the audience in a state of excitement, conveying a message from Schoenberg: the uncontrollability of music is like the world of the 20th century, with the masses always in a state of turmoil, unable to change the current situation or predict the future.

Furthermore, the unpredictability of Schoenberg's music is also reflected in the contrasts of dynamics. Schoenberg employed various dynamic markings to shape the music, causing significant fluctuations in loudness and softness, resulting in sharp, intense, and stimulating sound effects. He pursued sensory stimulation and exaggerated contrasts of intuition, with these musical techniques being driven by the modern concept of ugliness. [5]

Example 4: Measures 1-5 of the "Prelude"

In Example 4, it is clear that Schoenberg used a constantly changing approach of sudden loudness and softness to depict the uncontrollability of the musical direction. In the first measure, a contrast is made from a high voice's p to a low voice's mf, while in the second measure, the dynamics between the high and low voices switch, with the low voice changing to pp and the high voice to mf, especially the rapid transition from fortepiano (fp) to sudden softness in the third, fourth, and fifth measures. The continuous interjection of accents constantly challenges the audience's fragile nerves. In Schoenberg's musical creation, by dismembering the structure of music and destroying its inherent direction, he creates a different kind of stimulation for the audience by breaking the regularity of traditional classical music, and this stimulation brings a different kind of auditory pleasure. The audience's initial resistance turns into a novel experience. Exaggerated deformation techniques, fragmented tonal structures, elusive musical emotions, and the collapse of the boundary between subject and object further promote the transition from aesthetic activity to the activity of appreciating ugliness.

3. Conclusion

Schoenberg's "Prelude" excellently demonstrates the application of ugliness studies within expressionist music through its use of the twelve-tone system. This paper has analyzed and discussed the development of ugliness studies and the rhythm, meter, dynamics, and melodic direction of "Prelude" in conjunction with specific aspects of ugliness studies. Certainly, the application of ugliness studies is not only evident in Schoenberg's work but also widely present in other artistic domains. The occurrence of "ugliness" phenomena in modern art or works that contain "ugly" elements cannot be categorized within the aesthetic realm. Artworks related to "ugly" elements aim for visual and auditory extreme impacts, running counter to the aesthetic principle that centers on the embodiment of "beauty". Thus, explaining such works from an aesthetic perspective seems unsatisfactory. This is also true for musical compositions, whether it's the twelve-tone system introduced and promoted by Schoenberg, Berg, or Webern, or later avant-garde composers like John Cage; aesthetics is no longer the sole principle of creation. Therefore, when researching art movements and artworks of the 20th century and beyond, the academic importance of often underestimated ugliness studies becomes apparent. Ugliness studies, as a novel research perspective, play an indispensable role in the development of modern and contemporary art.

References

[1]. Ma, Q. (2013). On the development of Western music from the changes in 20th-century music. Popular Art and Literature, (17), 142-143.

[2]. Lv, X. (2020). The development and transformation of “new music” in Western 20th-century music. Voice of the Yellow River, (13), 168-169. https://doi.org/10.19340/j.cnki.hhzs.2020.13.139

[3]. Li, Q. (2006). Ugly, the study of ugliness, and ugliness studies. Northeast Normal University.

[4]. Fan, Y. G. (2008). Absurdity: The unfolding of ugliness studies and the generation of aesthetic value. Journal of Shaanxi Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), (01), 55-61.

[5]. Liu, Y. (2009). The entanglement of ugliness in sensuous continuity. Northwest University.

[6]. He, J. (2002). The threefold causes of the critique of ugliness in Western modern art. Journal of Xiangtan Normal University (Social Science Edition), (05), 114-119.

Cite this article

Fan,J. (2024). The Embodiment of Ugliness in 20th Century Western Music: A Case Study of Schoenberg's “Prelude”. Advances in Humanities Research,5,27-31.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Humanities Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Ma, Q. (2013). On the development of Western music from the changes in 20th-century music. Popular Art and Literature, (17), 142-143.

[2]. Lv, X. (2020). The development and transformation of “new music” in Western 20th-century music. Voice of the Yellow River, (13), 168-169. https://doi.org/10.19340/j.cnki.hhzs.2020.13.139

[3]. Li, Q. (2006). Ugly, the study of ugliness, and ugliness studies. Northeast Normal University.

[4]. Fan, Y. G. (2008). Absurdity: The unfolding of ugliness studies and the generation of aesthetic value. Journal of Shaanxi Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), (01), 55-61.

[5]. Liu, Y. (2009). The entanglement of ugliness in sensuous continuity. Northwest University.

[6]. He, J. (2002). The threefold causes of the critique of ugliness in Western modern art. Journal of Xiangtan Normal University (Social Science Edition), (05), 114-119.