1 La famille de saltimbanques

According to the accepted chronology, Picasso came upon a troupe of saltimbanques around mid-July 1904 as he strolled down the Esplanade des Invalides. The quatorze juillet was the traditional time for street fairs to pop up in the city. In contemporary avant-garde, these entertainers had become an important subject for artists, who—as nonconformists—identified with those rootless individuals, especially clowns. As Elmer Carmean indicates, by the close of the nineteenth century, there had been a mutual exchange in literature and art involving the circus performer, the saltimbanques, and the traditional Commedia characters (Carmean 1980, 25) [5]. Indeed, Picasso was not the first artist to draw inspiration from the solitary existence of these traveling entertainers. Modern artists such as Daumier, Cézanne, Degas, Seurat, and Toulouse-Lautrec had all delved into the artistic possibilities of the subject. Seurat's pieces conveyed a sense of sorrow and ceremonial gravity that would have certainly appealed to the Spanish artist. He would depict them on the barren outskirts of the city where many of these nomadic bands of mixed (often vaguely central European) origin, would set up their temporary encampments. Descendants of an itinerant culture that had first entered France during the fifteenth century, they formed a group for which the very word bohémien had originally been coined (Weiss 1997, 205) [47]. Their literary counterparts were the Romantic saltimbanques on the Parisian Rive Gauche, where Huysmans had described their performance taking place in a barren rural landscape, "a world apart … solitary and charming" (Reff 1971, 40) [33].

Some of Picasso's paintings depicted the actual harsh environment of Le Maquis de Montmartre. The performers, accompanied by their children and scarce possessions, could still be found wandering the streets with a monkey or bear on a leash. Their itinerant way of life symbolized freedom, but also instability and poverty. Sue Roe notes that, as a struggling foreigner, Picasso would have related to them on some level (Roe 2015, 80) [39]. The saltimbanque, highly favored in art and literature during the early part of the twentieth century, represented an idealized notion of the struggling artist wandering on the outskirts of society, completely dedicated to his craft. Picasso and his companions might have felt a connection with these entertainers, residing in their own unique world (Richardson 1991, 371, 386) [35].

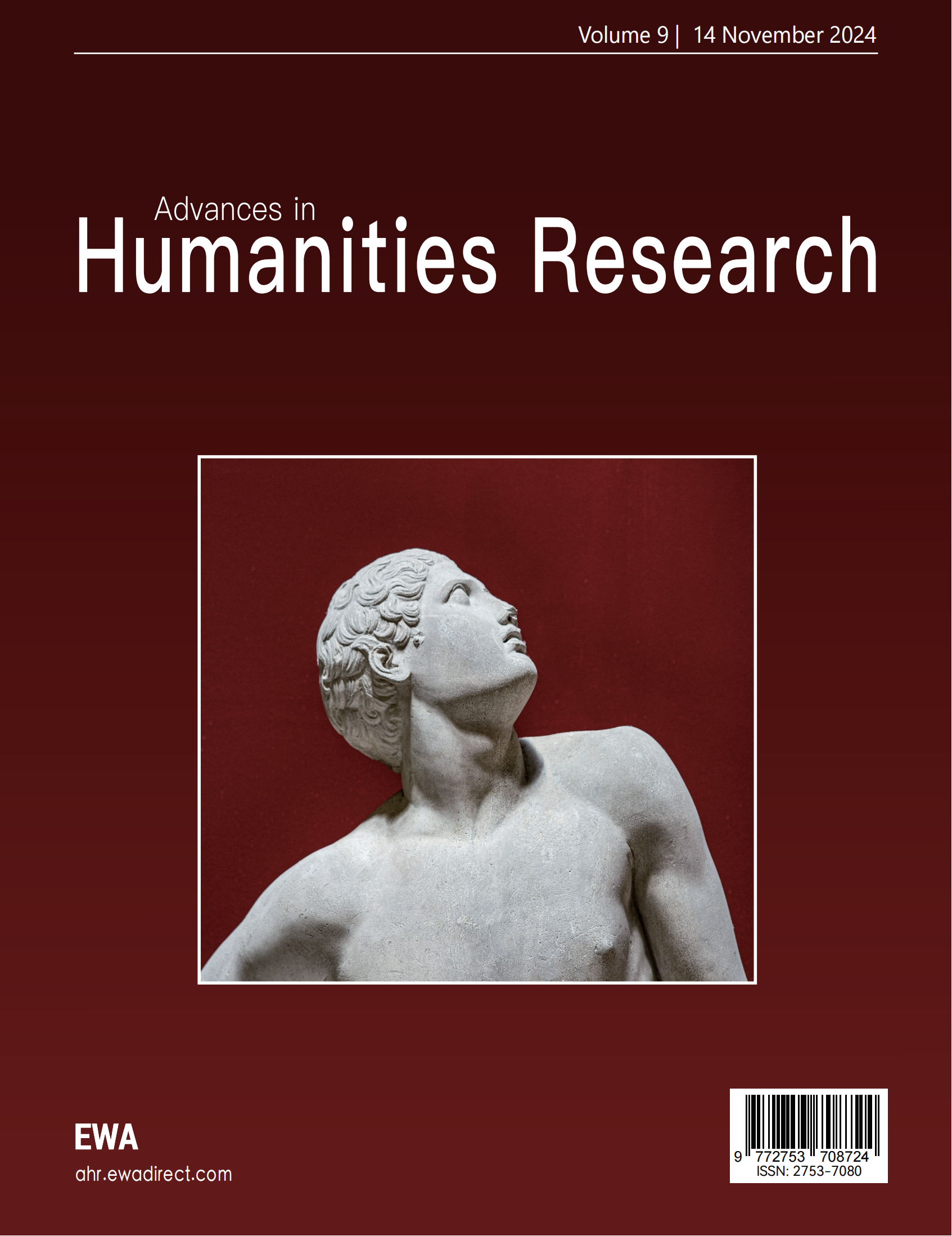

Figure 1. La famille de saltimbanques. Paris. 1905. Oil on canvas. 212,8 x 229,6 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. OPP.05:002.

The figure of the harlequin had already appeared in the artist's works. The character is identifiable in Arlequin accoudé by his lozenge-patterned costume, but as Raphaël Bouvier points out, the artist here also combined his traditional attributes with those of Pierrot, distinguished by his chalk-white face and black skullcap (Bouvier 2019, 63) [2]. Tinterow and Stein note that the harlequin costume, a patchwork of black and red lozenges separated by white bands, had been established by the mid-sixteenth century, and he usually carried a baton, or slapstick, and wore a black mask (Tinterow & Stein 2010, 46) [41]. Elizabeth Cowling describes how the treatment of the protagonist's outfit, represented as a bold chequerboard surface, flat and decorative, match the equally abstract arrangement of red and yellow flowers on the frieze above his head. The contours have been simplified although firmly drawn; and the very heavy, flat application of paint, familiar from the synthetist style Gauguin had developed, further emphasizes the unity of the surface. The French painter had had the reputation of an intrepid outsider so at odds with bourgeois values that he had been forced to lead the life of a savage in the South Seas—thereby escaping "civilization in which you suffer" and embracing "barbarism which is for me a rejuvenation." (Cowling 2002, 69–94) [9]. The painting may be interpreted not just as an homage to Gauguin's radical style, but as enshrining romantic fantasies about the artist himself.

A number of writers and artists, including Flaubert and Baudelaire had included these marginal individuals in their work, and Picasso's friend at the time, Max Jacob, was also an ardent fan of Verlaine and Laforgue, poets who frequently featured characters from the Commedia dell'Arte in their verses. As Carmean noticed, there was a reciprocal influence in the late 1800s between literature and painting centered around the circus performer, the saltimbanque, and the traditional Commedia figure. Harlequin was ubiquitous in popular entertainment, seen at masked balls, the opera, street fairs, the circus, and the cabarets. Upon arriving in Paris, Picasso tackled this dynamic interaction (Carmean 1980, 25) [5].

Ellen Bransten argued that the Harlequin could represent the objectified essence of Picasso's own struggles as an artist. He saw a resemblance between the Harlequin's exclusion from normal life and the isolation of an artist in modern society (Bransten 1944, 27) [3]. This is not the first time, the Spaniard had "inhabited" his creations without any reference to his own physiognomy. He often found ways to reflect his own interests and desires in his portrayals of others. Many of these sublimated selves may embody his private myths and superstitions or self-directed variety of animism and fetishism that constituted his own personal voodoo. Kirk Varnedoe suggested that the influence ran both ways between the worlds he created and the life he lived; "each shaped his understanding of the other, as his art allowed him … to construct and to discover, the complexities in himself" (Varnedoe 1996, 111–175) [46]. This process involved discovery, disclosure, and disguise in a synergistic dialogue. He wanted to use the signs he created to produce disruptively fertile ambiguities and uncertainties which often allowed contradictions to cohabit. Theodore Reff already commented that the subtle and elusive Harlequin was the closest thing to Picasso's concept of art as both disguise and revelation. The costume's flat, vibrant hues and bold designs both obscure and reveal the true shapes beneath, causing familiar traits to fade as the usually hidden aspects come to light (Reff 1971, 31) [33].

Although Picasso remained a typically penniless artist, he had reason to feel optimistic—and little by little, during the summer and fall of 1904, the still frequent blue gloom would slowly gain a slight rose tinge. Rendered in delicate veils of gouache and watercolor, Les saltimbanques bears witness to an important stylistic transition. Here a golden glow breaks through the airy, indigo wash that surrounds the intimately composed figural group—a family of entertainers taking a break from their performance (Richardson 1991, 304) [35]. Picasso had become captivated by the circus performances. As Reff notes, he recalled that there were times when he attended three or four shows in a single week (Reff 1971, 33) [33]. The traditional Cirque Médrano at the base of la Butte was the most popular such venue for several years. Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec, Forain, Seurat, and many others had found delight in its saltimbanques, jugglers, and clowns. Picasso would engage in conversations with these entertainers behind the scenes at the circus or amid the sideshows of the fair that typically spread out throughout the entire boulevard in winter. Without realizing it, they became his models.

Another big fan of these performances was the poet Guillaume Apollinaire. He was fascinated with the theme of traveling entertainers, performers of magic and illusion, who, similar to poets, evoked images of freedom, wandering through strange lands in the pursuit of their calling. As his biographer John Richardson notes, his encounter with Apollinaire would be one of the most significant in Picasso's early career. It took place in October 1904, when Manuel Hugué (Manolo) introduced him to the poet at the English bar Austin's Fox on rue d'Amsterdam (Richardson 1991, 327) [35]. The establishment primarily served the racetrack crowd coming from training places at Maisons-Laffitte, which was just a few railroad stops away from Gare Prison de Saint-Lazare. The poet often lingered at the bar until he mustered enough courage to catch the train back to the rented villa in the Le Vésinet suburb where he lived with his abusive mother. ''

According to Miles Unger, Manolo also introduced Picasso to the writer and art critic André Salmon, who soon moved into the Bateau-Lavoir where the artist lived and became another member of la bande à Picasso (Unger 2018, 173) [44]. In his poorly lit studio, the artist worked through the night, with a single lamp casting a dim glow. Propped against the dusty walls were the paintings he had brought from Spain. These melancholy compositions, painted in monochrome blue, had depicted destitute men and fragile women, bearing a resemblance to a blend of Toulouse-Lautrec, Steinlen, and El Greco, as Roe remarks (Roe 2015, 76) [39].

Pierre Cabanne describes how later in the month, Picasso took his friend Max Jacob to Austin's Fox to introduce him to Apollinaire, with whom he had felt a strong connection. Salmon had shown up at his studio and had come along with them to meet this person that had so impressed him (Cabanne 1979, 91) [4]. Jacob and he had met in 1901. It is likely that it was at this point, when he had gotten to know all three poets, that he wrote the words Au rendez-vous des poètes in chalk on the studio door, inspired by the names of Parisian cafés. This showed how the artist felt somewhat connected to their poetic world. Apollinaire advised him to abandon the remaining traces of sadness in his paintings and infuse his Andalusian spirit with a dose of Parisian joy. He urged him to identify with the theatrical strolling performer, not only as an intriguing outsider in conflict with society, but as a form of sorcerer, assuming the ambiguous persona of Harlequin Trismegistus (according to Richardson), a soul liberated from hell (Richardson 1991, 333–334) [35]. Much has been made of the excellent relationship Picasso had with Apollinaire. As Peter Read has stated, the poet's mental landscape and poetic practice also brought to the artist's studio a new model of imaginative and creative diversity (Read 2011, 158) [32].

The clown, the performer, the Harlequin came from a lineage of creative individuals. Picasso would link their expertise and bravery in a setting known for its unpredictability and risk. The memory of that troupe of saltimbanques he had seen back in 1904 along the Esplanade des Invalides had stayed with him and now triggered an increased appearance of these characters in his paintings. The Spaniard adored the relaxed atmosphere of the circus and the popular theater, the agile acrobats, the contrived gesturing of the actors, the amusing clowns. These professionals were regarded as skilled artists, and to that extent Picasso could relate to them. The theatrical performances between the circus acts often featured not just Pierrots and Harlequins, but also illusionists, conjurers, and magicians of all kinds. As Roe points out, they seemed to inhabit an alternative universe, a world of vigor and amazing stunts, the contemplation of which took Picasso out of his own current situation and the preoccupation with social injustice (Roe 2015, 116–118) [39]. Varnedoe notes how those earlier experiments to mirror himself in the rejects of society were replaced by a new strategy to shift his identity beyond time and into the realm of ideals. Le saltimbanque is a metaphoric representation (Varnedoe 1996, 111–175) [46].

Reff wrote that Picasso seemed most attracted to the traveling acrobats, or saltimbanques, of the lowest order (Reff 1971, 42) [33]. Yet, those pictures got the attention of wealthy collectors. The prominent Parisian businessman André Level bought six paintings and watercolors from two of his occasional art dealers, Berthe Weill and Père Soulié. As Michael FitzGerald explained, Level had created an association called La Peau de l'Ours (FitzGerald 1995, 271) [14]. Its eleven members contributed an annual subscription of 250 francs that he was then authorized to invest on the purchase of artworks. He visited galleries and studios to discover young artists, whose paintings he then proposed to his associates. Each one he bought was distributed to a member of the group, chosen by lottery. It was agreed that all the items would be put back on sale ten years after founding of the association. A part of the profits would then be paid to the painters.

Despite his increased success, Picasso and his circle continued to frequent inexpensive eateries, coffee shops, and cabarets outside his Bateau-Lavoir studio, with Au Lapin Agile, owned by his friend Frédé, being a popular choice. In 1904, Picasso created a self-portrait as a Harlequin with his companion at the time, Germaine, and gave the painting to Frédé to be displayed in the main hall. According to David Riedel, Fernande began a more serious relationship with him this spring (Riedel 2011, 77) [37]. She remembered that, in an environment dominated by artistic endeavors, the options for cheap entertainment were scarce. She observed that Picasso would spend entire evenings at Cirque Médrano, one of the few places where he could relax, chatting and joking with the performers. Afterwards, everyone crowded into the Hôtel des Deux Hémisphères on rue des Martyrs, a popular bar frequented circus performers and their acquaintances, including people from all nationalities and walks of life. Salmon sarcastically commented that there were more Spaniards there than he had ever seen in Spain.

The splendid Cirque Médrano, with its lions, elephants, white horses, trapeze artists, jugglers, equestriennes, acrobats, actors, and clowns, matched Picasso's preference for popular entertainment. He loved the smell of the crowded tents and booths, and also admired the artistic integrity, and the dedicated professionalism of the people that worked and lived there: it was a multi-national atmosphere where language was never a barrier, a world separate from his usual routine, made up of outsiders whose contact with the public was confined to their performances, which often involved skilled performances, the fruit of endless rehearsals. One of the frequent acts involved graceful equestrians in skimpy, spangled costumes doing stunts on the backs of white horses.

As Tinterow and Stein point out, several contemporary writers had equally explored the connection between acrobats and artists. André Salmon, for example, discussed this theme in his early poetry. His initial collection of poems, featuring the frontispiece Les deux saltimbanques, included a poem directly likening himself to a tightrope walker. The subsequent volume, released in 1907, contained a poem honoring Rimbaud as both an "angel and demon, poet and acrobat," as well as a poem depicting the romance between a circus clown and a tightrope walker, and another where a gypsy acrobat, reflecting on his life experiences, parallels his destiny with that of the poet, much like Baudelaire's Vieux Saltimbanque (Tinterow & Stein 2010, 78) [41].

In some pictures of the time such as Acrobate et jeune arlequin Picasso portrayed the melancholy of these itinerant professionals. It is visible, for instance, in the manner in which the older character rests his hand on the younger one, a gesture also seen in Comédien et enfant. The tall figure wears a long cape and feathered hat. A similar outfit appeared in other depictions of actors like the important watercolor Les comédiens. The small boy, having been depicted all in blue in Comédien et enfant, is transformed in Acrobate et jeune arlequin into the dazzlingly multicolored Harlequin. By merging the circus with the Commedia dell'Arte, the artist gave these familiar motifs his own poetic twist. Cowling has noted how he often represented these professionals as archetypes—the thin but elegant Harlequin; the pretty but fragile mother; the famished acrobat with his dreamy expression; the fat clown; the petite equestrienne, etc. These transformations were at once chromatic and psychological, physiognomic and technical. Sometimes a switch in the protagonists called for a choice of medium and support—pastel, oil; paper, canvas, etc.,—which also determined a change in implementation. The delicate, hazy palette of pastel blues and pinks contributed to the fictional atmosphere; as did the vaguely sketched settings and scenery, which are made to look impermanent and illusive thus defining the subject matter as imaginary, transient and ambiguous (Cowling 2002, 118–131) [9]. The sitter was often depicted as an androgynous figure, one described by Apollinaire as being of "sexes indistinct" (Bouvier 2019, 174) [2].

The drypoint Les saltimbanques, in a general sense, expanded on the theme of poverty and alienation from the Blue Period, portraying these figures in a symbolic, unidentified setting. A poignant example is the elderly woman washing dishes at the bottom center: her stiff, angular shoulders, her downward gaze, drooping neck, and slender, upright arms closely mirrored those of a figure in his La repasseuse.

The woman and child on the right, carrying firewood, represented earlier types to a lesser degree. However, the central focus of the composition remained acrobatic rehearsals. The Harlequin, with hands on hips, observed the young acrobat balancing on a ball. It is evident that she is a new creation, embodying the concepts of balance and athletic grace as the circus theme developed. Their distinct features, slender figures, and elongated limbs and fingers continued to portray not only hunger and poverty but also a frail existence at the edges of society (McCully 1992, 53) [28]. As Cabanne notes, in works like these, the blue monochrome's firmness and authority transitioned into a delicate multicolored fragility (Cabanne 1979, 97) [4].

Famille de bateleurs is related to the above drypoint in its combination of the themes of motherhood, Harlequin, and acrobats into a single work portraying a despondent family of entertainers. The word bateleurs comes from the old French word basteler, which referred to someone who played with small batons called basteaux, and originally denoted a juggler. Its roots can be traced through the medieval church in France all the way back to Roman culture. As Carmean notes, in the eighteenth century, they became linked with forains, itinerant merchants who hired them to draw in customers to their performance (Carmean 1980, 18) [5]. In earlier sketches, the characters had been few and spread out, but now they appeared all interconnected as if purposely preventing any interruption of continuity. In the course of his work on La famille de saltimbanques, he tried to position himself within the tight, closely connected structure. This objective is especially clear in a drawing he kept, which shows the palm of a hand with four figures next to it, with their relative heights matching those typically found in the four fingers. In the first studies for the large canvas, a child is trying to balance on a large ball. The focal figure however was the Harlequin, standing with his elbows bent outward and hands on hips. This character would take the same formal stance in La famille de saltimbanques.

Throughout his life, Picasso always remembered the important advice his father had given him: to use a large canvas to convey a crucial message. So it is clear that this artwork's meticulous preparation and its large size were intended to emphasize its prominence (Unger 2018, 304–305) [44]. As he started transferring the sketch on the prepared canvas, he grew discontent with the initial idea as it seemed more fitting for a drawing and not for a grander composition. His initial concept of an extended family group was then reduced to just two acrobats with a dog. Nonetheless, that would have made the expansive canvas appear bare, so he attempted another approach by arranging figures closely around the rotund form of El Tío Pepe, one of the troupe's clowns (Richardson 1991, 382) [35]. At this time, Apollinaire and Picasso were spending almost every waking hour in each other's company, so it is not a big surprise that Tío Pepe should also bear a striking resemblance to the poet.

In the most worked-up sketches for the final composition, La famille de saltimbanques (Étude), done in late summer, there was a surprising turn of events: the background briefly featured a racetrack scene reminiscent of Degas. The fast-moving horses created a lively contrast with the stationary saltimbanques. However, he concluded that this would distract from the desired effect. Ultimately, he opted for a simple, desert-like setting "transitioning from the world of genre to the world of allegory" (Bouvier 2019, 165) [2]. The male traveler with a top hat and wrapped up in winter clothing hides a Harlequin's leotard, hardly outlined. A little girl holds his hand. Beside them is the obese jester we have seen before. While other small changes would be implemented, he would stick, for the most part, to the same arrangement except for the dog on the right of the composition that would be discarded. In the final version, none of the characters look at each other, which heightens the sense of isolation. The figure wearing a top hat on the left is evidently a self-portrait. In this major composition, Picasso intended to present himself as a member of the larger bohemian family, a dangerous class living on the fringes of society. He was familiar through his attendance to the Closerie des Lilas discussions with the concept of the bas-fonds as a realm of lurking menace, where defiance of established rules constituted a form of covert dominance over the city. It is through their association with an actual subculture that the community of Villonistes experienced Paris as "a city seized from within" (Weiss 1997, 204) [47].

The completion of La famille de saltimbanques occurred during the late part of autumn. The cohesive nature of the composition is rooted in the overall poetic ambiance rather than the specific details that one might discern. The general sense of restrain is emphasized by the fact that the two figures nearest to the observer are depicted from behind. In this presentation piece, Picasso wanted to include the three poets that had been a great influence on his new style. He depicted Max Jacob's features and small stature in the small wandering acrobat in the background. The taller acrobat carrying a drum on his shoulder recalls the description of André Salmon in Fernande's memoir as being a tall, thin man. The solid acrobat or clown in a red outfit once again clearly looked like Guillaume Apollinaire. The artist might have seen himself and his friends in the characters he painted, giving us some understanding of his creative process, but it doesn't completely clarify the significance of this important painting. The seemingly inconsequential scene has the power to create intense drama. The artist not only removed any indications of a particular time or place and any remnants of a storyline, but also rendered his life-size saltimbanques as motionless as the figures in a Renaissance fresco. Despite closely intertwining the various characters on the surface, their connections remained largely mysterious. Picasso created an atmosphere of open-endedness, which prompts the viewer to perceive it as magical or poetic, aiming to mask, rather than unveil reality.

The painting's original tonality featured some blue hues, although not as strongly as previously. However, the final colors include varying shades of red and blue, as well as combinations of yellow with blues and browns. The color effects are subtle, reduced to a discreet, unobtrusive harmony which endows the painting with a calm, oddly elegiac charm. The Harlequin's hand was twisted behind him, seemingly reflecting the emblematic mystery of the picture. As Richardson explains, in addition to palmistry, there is a hint of the Tarot (Richardson 1991, 382–385) [35]. The strolling players are adrift in a landscape without an audience, wanderers in search of a context that could give them meaning. The work would inspire the opening lines of Rilke's Fünfte Elegie: "Who are they, tell me, these homeless ones, these more fleeting / even than we ourselves" (Rilke & Boney 1975, 90–97) [38].

Two years after completing it, Picasso finally decided to unload La famille de saltimbanques. At that time, Picasso's dealer, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, presented it to a customer of his, Sergei Shchukin, who had reaped significant profits in 1905 by monopolizing the textile industry, speculating that the political crisis would soon be resolved, and had kept substantial funds outside of Russia to support his art purchases. According to FitzGerald, the gallerist Clovis Sagot heard about it and informed André Level, who immediately showed interest. To cut off other potential buyers, Level made an offer of 1,000 francs through Lucien Moline. Hoping for a higher price, the painter did not initially go for it, but the "La Peau de l'Ours" group eventually ended up acquiring it (FitzGerald 1995, 31) [14].

By 1914, it was time to auction the works the members of the investment group had purchased. In the space of ten years, they had accumulated a large number of pictures by a wide range of painters: Van Gogh, Gauguin, Odilon Redon, Vuillard, Maurice Denis, Bonnard, Vallotton, Signac, Sérusier, Maillol, but also Dufy, Laprade, Utrillo, Valadon, van Dongen, Herbin, Dufrénoy, Flandrin, Roger de La Fresnaye, Othon Friesz, Marquet, Manguin, Metzinger, Rouault, Dunoyer de Segonzac, Verhoeven, Vlaminck, Derain, Matisse, Laurencin, Willette and Picasso. The sale of "La Peau de l'Ours" collection took place on March 2. One hundred and forty-five works, with eighty-eight paintings and fifty-seven drawings by sixty different artists on display in rooms 6 and 7 were sold at auction with Maître Henri Baeudouin wielding the ivory gavel, flanked by the Bernheim brothers and Eugène Druet, the appointed experts. The twelve Picassos were all pre-Cubist works. As the large canvas La famille de saltimbanques was placed on the stand, the starting price was set at 8,000 francs (André Level had bought it for 1,000 francs). When Heinrich Thannhauser made the final bid at 11,500 francs (49,602.95 dollars at the current value), there was an immediate uproar. Franck mentions that Salmon called it a "Hernani of painting" (Franck 2001, 158–159), referring to the well-known clash between Romantic and Classicist groups sparked by the initial showing of Victor Hugo's play Hernani in 1830. To make matters worse, Thannhauser was quoted in Gil Blas as saying he would have "willingly paid twice as much." The total result of the auction was 116,545 francs, the quadruple of the purchase cost (27,500 francs over a ten-year period), and Picasso alone was responsible for a quarter of the huge gain: 31,301 francs was paid for works by him, of which he received 20%, i.e. 12,641 francs. As reported by FitzGerald, this would constitute one-fifth of his recorded income for 1914 (FitzGerald 1995, 44) [14]. Kahnweiler rushed from the saleroom to give him the great news. As soon as those incredible numbers were made public, an anti-German campaign was launched in the press. Two decades later, the American couple Maud and Chester Dale acquired La famille de saltimbanques from the Valentine Gallery, New York (Geelhaar 1993, 179) [17]. Picasso's marketability seemed to be on the increase in the 1930s despite of the financial crisis triggered by the Great Depression. After purchasing it at the Peau de l'Ours, Thannhauser had sold it to Hertha von König, who, in turn, had used it as a collateral to secure a loan after the economic crash. Dale heard from Valentine Dudensing, his dealer in New York, that the painting had been repossessed and now resided in a Swiss bank vault while a consortium of dealers bargained with the bankers over an asking price that may have approached 100,000 dollars. Understanding bankers' usual desire for cash rather than for illiquid property, Dale had Dudensing cabled a much lower offer, with a deadline of twenty-four hours. The bank accepted the bid. He acquired the painting for the sum of 20,000 dollars, a substantial price.

After the death of Chester Dale in December 1962, the majority of his collection, including La famille de saltimbanques was bequeathed to the National Gallery, Washington, DC.

2 Les demoiselles d'Avignon

During the autumn of 1906, Picasso, Apollinaire, Jacob, and Salmon often joined Henri Matisse for dinner. Jacob later mentioned that it was at Matisse's home where Picasso encountered African art, or at least where he first took a serious look at it (Madeline 2006, 198) [26]. On the contrary, Matisse insisted that he had discussed African sculpture with Picasso while they were at Gertrude Stein's apartment on rue de Fleurus. In any case, it is likely that both Matisse and Stein each had a share in the artist's first encounter with these objects, which both of them collected them.

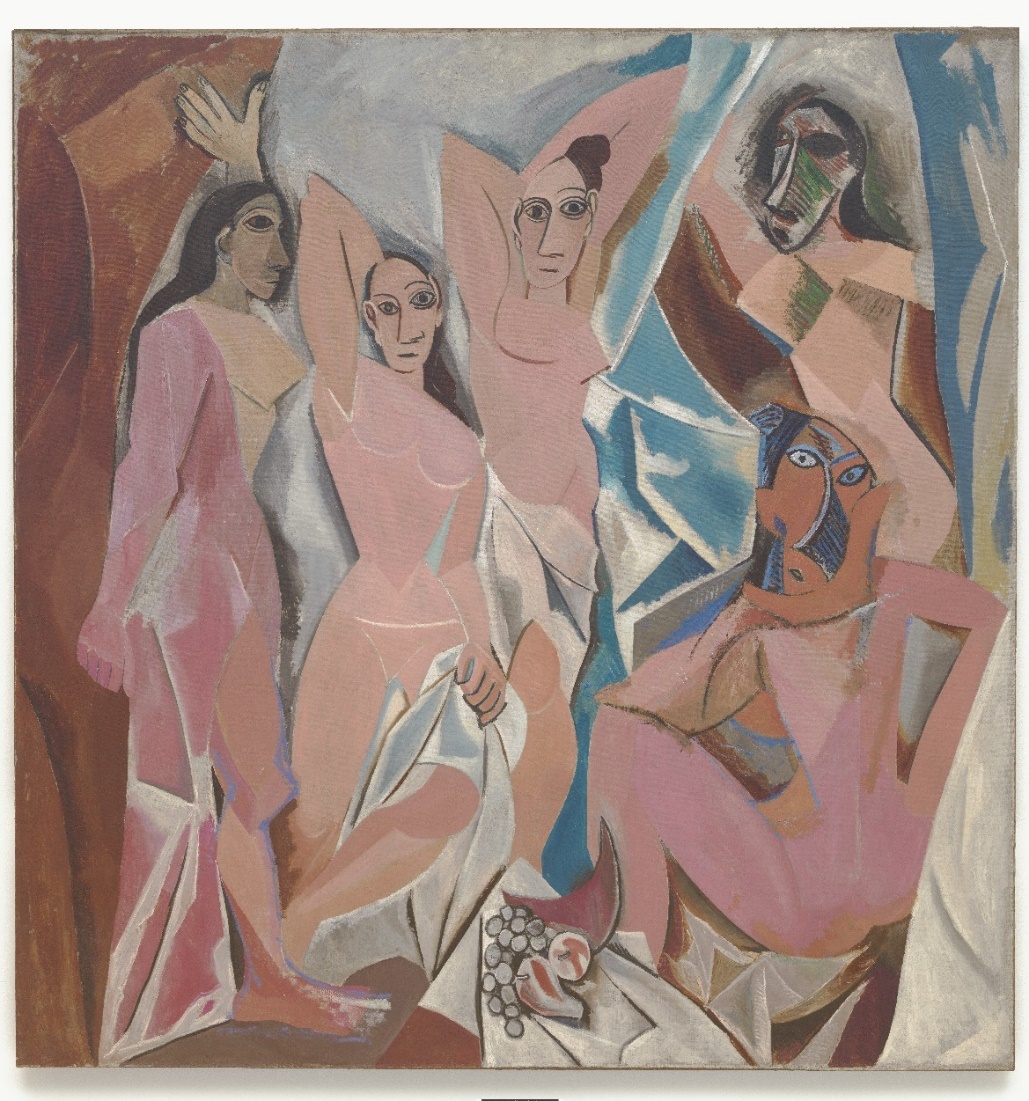

Figure 2. Les demoiselles d’Avignon. Paris. 1907. Oil on canvas. 243,9 x 233,7 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. OPP.07:001.

Maurice de Vlaminck and André Derain had both already developed a strong interest in African art as well. They could be easily acquired for a minimal cost at Saint-Ouen or in the rue Mouffetard, among other places. During the fall, Vlaminck bought his initial sculpture from the Congo, a nineteenth century Vili statuette, from Emile Heymann's shop on rue de Rennes. Heymann, also known as "le Père Sauvage," specialized in selling such exotic curiosities. Vlaminck later stated that he had been intrigued by Negro masks as early as 1904 and had managed to pique Derain's interest in them. In fact, the latter ended up purchasing a Fang mask directly from his friend. All this shows that these masks were becoming widely available, sparking the curiosity of individuals with a penchant for the exotic, providing new source of inspiration for those tired of the same old subjects.

Few knew, however, that African tribal sculpture had frequently served a distinct purpose and manifested a nonrational attempt to appease supernatural powers. The act of sculpting itself was ritualistic, as the thinking involved in giving shape to these unseen entities simultaneously controlled them, thus empowering the sculptor. Picasso was well aware of this and felt a connection to those artists-magicians. The artist believed that African figures and masks were associated with supernatural powers and possessed a sacred ritual energy. Salmon once called him "an apprentice sorcerer," and Blaise Cendrars wrote that his works reminded him of "black sorcery" (Choucha 1992, 25–33) [7].

Knowing of his friend's interest in primitive art, Derain urged Picasso to visit the Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro. He, Vlaminck, and Matisse recognized the potential of tribal art as a catalyst. However, Derain had his doubts about how these objects could be integrated in modern art. By encouraging Picasso to visit the museum, he was passing on to the Spaniard the risk of exploring that path. The experience would be exhilarating: "I understood what Negroes used their sculpture for … The Demoiselles d'Avignon had to happen that very day, not at all because of the forms: but because it was my first canvas of exorcism" (Gilot & Lake 1964, 248) [18]. In the end, Vlaminck would acknowledge that Picasso was the one who had immediately grasped the insights one could glean from the sculptural representations of African art (Flam and Deutch 2003, 28) [15].

Picasso immediately proceeded to paint several monstrously distorted female nudes, as seen in the small painting Trois nus (Étude), in which the expressionism was not tempered by any affected charm. This is one of the first studies for Les demoiselles d'Avignon The intentional unattractiveness of those figures was extremely confrontational; it not only deviated from the conventional idea of beauty, but it ruthlessly attacked the human body. 'Irving Lavin emphasizes that Picasso wasn't just exploring a new approach within an established practice; he was critically reinterpreting the fundamental principles of art in a profound and thoughtful manner (Lavin 2007, 55–56) [24]. Picasso now viewed art as a shamanic practice focused on controlling the hidden forces that govern human destiny at its core. He believed that the key to finding an artistic language capable of portraying the disruptive, uneven realities of modern life had to come from tapping into ancient modes predating the layers of civilization that disconnected people from their true selves. The breakthrough occurred when he found the means to access the magic inherent in all artistic creation, most vividly manifested in the art of these so-called "primitives" (Unger 2018, 263) [44].

At this turning point, Picasso also realized that in order to achieve purity of plastic vision his art would have to acquire complete independence from emotional content, anecdote and even subject-matter altogether. One day, a friend, Henri Mahaut, heard him dismiss his previous work from the Blue and Rose periods with the contemptuous remark: "All that is sentiment" (Vallentin 1963, 76) [45]. The change, however, came gradually. He started filling sketchbooks with studies such as Quatre nus: étude pour Deux nus and Deux nus: nu assis et nu debout (Étude) for a multifigure composition on the theme of the bordello (Golding 1968, 48) [20]. These preparations seem to have been begun as a response to the challenge of Matisse's recent work and to his discovery of African art. Picasso referred to the brothel as the only place where "there are truly nude women nowadays" (Karmel 2007, 150) [23]. He would paint them in the tradition of Ingres's Le Bain turc or Cézanne's Les Baigneuses, but using that new approach he was developing. In one of the drawings, Les demoiselles d'Avignon: ensemble à sept personnages (Étude), five women are gathered around a seated man, to whom they pay no attention, although they also seem to be welcoming a man who enters from the left. The man in the middle is clearly a sailor, next to whom is a plate of sliced watermelon; the young man they turn their attention to raises the drapery with one hand and clutches his book (or occasionally a skull) in the other. Picasso's mind was in a ferment. As the studies progressed and as he came to grapple with the real issues at stake, the sailor would vanish, leaving only his melon, grapes, pear, and peach; and by the time the final composition reached completion, only five prostitutes would remain. Their humanity had been abstracted, wiping out all trace of morality or anecdote.

In the beginning of spring, Picasso bought a big canvas with the intention of putting down "the first outcome of his artistic experiments" (O'Brian 1994, 150) [29]. As mentioned earlier, its large size signaled the importance it had for Picasso as a major statement. Recently, he had been neglecting the quality of his supports, but this time, he opted for an especially costly, finely textured cotton canvas. Leo and Gertrude Stein funded a second studio for him in the Bateau-Lavoir to fit the big frame. It was a dim room located on the lower floor of his main studio, serving as a secluded space where he could isolate himself from any interruptions. He immediately delved into preliminary works such as Femme au corsage jaune and other related studies of figures standing rigidly, facing forward, with hands clasped at the groin, a stance that appears to have held a distinct and significant meaning for him. The exceptional studies, although informal, were crucial in his preparation for the final painting as they document the mental process of working out body proportion schemes. In late March, he began getting the canvas ready for the next phase, as witnessed by Leo before his departure for Italy: "I had some pictures relined, and [Picasso] decided that "he would have the canvas lined first and paint on it afterwards" (Stein 1947, 175) [40].

We have some witness accounts of those who saw the work in progress. Even in its early stages, the common reaction was complete incomprehension. A postcard dated April 27 and addressed by Picasso to Gertrude and Leo Stein at their Paris residence bears only the following words: "Please come Sunday tomorrow to see the painting" (Golding 1958, 160) [19]. From an express letter conveyed by pneumatic tube and sent to Uhde, we also know that he invited him to the studio to see his work. Uhde later wrote: "Vollard and Fénéon had paid him a visit but had left without understanding a thing" (Uhde 1938, 142) [43].

According to Kahnweiler, it was in early May that Georges Braque came to see it, accompanied by Apollinaire (Kahnweiler 1949, 16) [21]. Apparently, the desired effect was not yet strong enough. Soon after this initial visit, Picasso altered the sex of the medical student entering the bordello—all it took was for a shoulder to become a breast and for hair to come flowing down his back— The women are now effectively revealing themselves. This was followed by another change: he decided to eliminate one of the female figures, the one who formerly stood at the left leaning on the chair of the seated woman. The composition, still dominated by the caryatid with her arms above her head, had by now tightened into a square, somewhat higher than wide, which signals the format of the final painting. As he worked on it, he added Negroid heads with widely striated cheeks, masks formed like scythe strokes with hollow sockets. The pink and gray nudes were now as robust as tree trunks. The large number of overlapping sketchbooks he filled as he worked on this canvas document a period of intense work, and is indicative of the huge commitment he had made to this particular piece, possibly the most thorough (and exhausting) research any creator has ever undertaken on a canvas of similar size.

In June, he decided to do away with the last surviving male figure, and the sailor vanished, leaving the female characters to themselves, frozen within the dense folds of the drapery that had become one with their bodies as seen in Les demoiselles d'Avignon (Étude). Their full exposed flesh and intense eyes, ostensibly turned toward the spectator-voyeur, no longer left any doubt as to their identity. Brigitte Léal describes how the flat shapes of their deformed bodies are merely suggested by the spaces between the lines, while their faces, reduced to masks, are dominated by noses shown in profile, schematically drawn ears, and bulging eyes (Léal, et al. 2000, 107–110) [25]. To illustrate the process that took place as he went from the initial vision to the definitive form, Picasso would touch his forehead and say. "Everything that happens is here" (Vallentin 1963, 10–11) [45]. He was aware that the African sculptor tended to depict what he knew about his subject rather than what he saw. As John Golding indicates, the finished work has the quality of a symbol—a re-creation, rather than a reinterpretation (Golding 1968, 47–60) [20].

To Picasso, the sculptures from Africa appeared "logical" as they embodied their subjects rather than just depicting them. Tucker argues that the painter worked under the spell of a new conviction that art, in its essence, was not simply about beauty but rather a mechanism for influencing concealed elements in the cosmos (Tucker 1992, 100–116) [42]. As he continued working on the relined canvas in late June, he changed the poses of the women on the right and far left so that they looked at the viewer, turning beholder into customer; and from there, he altered the painting with increased savagery. As an African sorcerer, he attacked the faces, most of whose noses were rendered from the front, in the form of isosceles triangles. Although the space represented was one that transcended normal spatial (and temporal) boundaries, and clearly was not intended to be a "real" place, its multiangle features reinforced the broader subject of the painting.

He expanded the outlines of the figures, increased their size, smoothed them out, and rearranged them on his canvas; he coated them with unvarying hues, similar to the way Africans painted their sacred objects and amulets. The artistic transformation it brought about in how we see things would be a significant aspect of the neo-primitive movement in 20th century's art, a desire to rekindle a sense of mystical experience. Turner contends that one of the many characteristics of modern art was its provocative nature and its spiritual endeavor, as it proposed a new vision of reality. One that is not preestablished, but is molded by the artistic materials and structures, evolving through the artist's full engagement with the medium. This visionary process is what endows modern art with the capacity to be genuinely transformative.

Everything in Picasso's 1907 important canvas teaches us of the inadequacy and randomness of customary visual representation. The look of at least two of the women were intensely lacking in emotion, with expressions that remained unchanged. As Roe argues, the feeling of being trapped in the instant only intensifies the confusing effect of the canvas. It is challenging for viewers to arrive at a consistent understanding of the image. As the eye travels from left to right, mimicking the movement in a traditional artwork, one transitions from bare, intense faces to those that are masked. Thus, looking from left to right does not offer any apparent link between the characters. The desired effect comes precisely from the contrast and the discovery that the arrangement of those images lacked any coherence. According to Unger, the purpose was to maintain the shock of such confrontation, leaving it unresolved (Unger 2018, 325–327) [44].

In its final version, the pink and ocher bodies of the five women appear almost devoid of modeling, arranged in a low left to right diagonal anchored by a squatting figure on the lower right. There was still an underlying reference to Ingres (Daix & Rosselet 1979, 14–15) [13]. For sure, his goal with such an important work had been to measure himself against the giants. The combination of the lowest brothel scene and the loftiest style was as explosive as anyone could have wished for. The three women on the left still showed Iberian mask-like faces; one head in profile features a full-face eye and two full-face heads show the nose in profile, as sharp as a wedge of cheese. On the right, the violence of distortion reaches a new pitch: the face of the squatting female, turned right round over her back, had its features savagely jumbled, and the woman above has a long ridge for a nose, strongly hatched to give it height, very much like Congo masks: neither of these heads was of the same nature as the other three, and in this half of the picture, all the angular planes—drapery, breasts, interstices—were sharper, much more definite (O'Brian 1994, 150) [29]. Once these changes were implemented, the figures appeared to obey mutually contradictory principles, although they were simultaneously united by a general geometrical structure that superimposes its own laws on the natural proportions, making them merge almost completely with the background (Walther 1993, 37, 40) [48]. The rounded contours of the figures had metamorphosed into a series of hard-edged shapes (principally mandorlas and triangles) that lie flat within the picture plane (Karmel 2007, 150–151) [23]. The asymmetrical arrangement has no single focal point and the spectator's eye is constantly pulled to new details. Cowling notes that the impression of disunity and disharmony is intentionally exacerbated by the extreme congestion of the composition (Cowling 2002, 160–180) [9].

He felt that he needed to see the reaction of some of his most devoted admirers to the canvas at this later stage. Picasso, without mentioning a date, told Édouard Pignon that Fénéon had made jokes when he eventually saw the painting, and he told Parmelin that the critic advised him to take up caricature (Parmelin 1966, 37) [30]. Matisse came with Leo Stein, and the two, in a fit of laughter, supposedly invoked the fourth dimension. He had meant for the canvas to be his great coup de théátre, shifting the focus of the drama away from the behavior of the figures within the painting and onto the viewer, who thus became leading players in the psychological and pictorial structure of the canvas. But his friends failed to see the point he was making. One person that did understand the importance of the canvas was Kahnweiler. He had been on the lookout for such radical innovations to show in new gallery that opened July 11 at 28, rue Vignon. Picasso had gine to check it out, and returned the following day accompanied by his dealer at the time, Ambroise Vollard.

Kahnweiler had heard about Les demoiselles d'Avignon from Uhde. He remembered having seen the painting "in early summer" (Kahnweiler 1971, 38) [22]. He was bowled over by the still unfinished painting. As some of Picasso's friends who saw the work at this stage, he was also shocked. But in this big canvas, he observed how the artist had begun to see the fundamental processes and principles of art differently. It was a question of identifying himself with the formal concepts of the primitive mentality and applying them to the problems of the modern painter. Les demoiselles d'Avignon has been called a cathartic painting, a great cry of anguish and release—a form of black magic in which Picasso summoned his demons in order to vanquish them. As he eventually explained to André Malraux, "if we give spirits a form, we become independent" (Unger 2018, 322) [44].

By the end of summer, the artist had set the large painting aside for good. In its ultimate form, the canvas had shifted from a conventional narrative to a composition where the audience is compelled to decipher its significance. The five women present themselves to us, embodying both charm and terror simultaneously; their accusatory gazes immobilize us, evoking Steinberg's memorable expression, "the shocked awareness of a viewer who encounters a reflection of oneself." Following this masterpiece, many of Picasso's paintings would emphasize abstract shapes and rhythmic structures lacking any intended connection with real-world surroundings, but projecting the force of a new vision. According to Pierre Daix, the era of science had begun, the period when, to accurately depict physical events, scientists and artists were forced to abandon the realities of the physical world and the logic of everyday life (Daix 1965, 66–68) [11].

Between November and December, Matisse and Derain went together to see Les demoiselles d'Avignon in its final state in Picasso's studio. Matisse was troubled by the finished canvas. He perceived it as an obvious mockery of serious art; he declared it was intended as a direct insult to him. He had no doubt been alerted by Leo Stein's having found the painting to be a "horrible mess"—and most likely went to the studio after the furor of the Salon d'Automne. André was probably equally shocked. Salmon wrote: "Some of his painter friends were now giving him a wide berth" (Cousins & Daix 1989, 348) [8]. By mid-November, Braque had also returned to Paris for Friesz's exhibition at the Galerie Druet (November 4–16). It was probably shortly after his arrival that he went with Apollinaire to the Bateau-Lavoir. The impact it had on him was huge. By Fernande's description, his response was to tell Picasso: "It is as if someone had drunk kerosene to spit fire," as fairground cracheurs de feu (Richardson 1996, 83) [36]. Others translate the comment differently: "It's as if you wanted to make us eat dung and drink black oil" (Franck 2001, 100) [16]; or "It looks as if you want us to eat fire" (Daix 2007, 22). The artist turned the canvas to the wall and kept away from viewers for decades, but the seed had been planted. Following this major piece, and together with Braque, he would explore new true nature of art as creation.

Sadly, it would not be until 1923 that this major contribution to art would be purchased by the fashion designer Jacques Doucet with the assistance of another major pioneer, the surrealist writer André Breton (Baldassari 2006, 233) [1]. The final agreed price had been 25,000 francs (30,570.28 dollars at the current value), to be paid in monthly instalments of 2,000 francs (Revel 1961, 51) [34], a low amount that Picasso only accepted because he foresaw his masterpiece might end up in the Louvre, to which Doucet had promised to bequeath it (Chapon 1984, 297–298) [6].

In 1925, La Révolution Surréaliste (no. 4) reproduced Les demoiselles d'Avignon on page 7, the first time it had been seen since 1910 when it appeared in the American review The Architectural Record, photographed by Man Ray (Daemgen 2005, 27) [10]. In Breton's essay "Le Surréalisme et la Peintre," published in the same issue, he declared: "Picasso does not only decompose and destroy, he invents new anatomies, new architectures and a new synthesis" (Penrose 1981, 251) [31]. Even two decades after its creation, the painting continued to impress artists in the avant-garde.

Les demoiselles d'Avignon went to Mme Doucet after the death of her husband in 1929. In November 1937, it was purchased from her by Jacques Seligmann and Co. for 260,000 francs. Exactly two years later, the Board of Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art, New York agreed to purchase it from Seligmann for 28,000 dollars, with the proceeds from the sale of a Degas painting donated by Lillie P. Bliss (18,000 dollars) plus an additional 10,000 dollars.

Interestingly, of these two important canvases, La famille de saltimbanques has not been featured in important exhibition with the exception, perhaps, of Picasso: The Early Years 1892-1906 at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Conversely, Les demoiselles d'Avignon has been acclaimed as a major breakthrough in art history, and has been regularly featured in major Picasso retrospectives, such as "Twenty Years in the Evolution of Picasso, 1903-1923", "Picasso: Forty Years of His Art", "Picasso, 75th Anniversary", "Picasso. Retrospective 1895-1959", "Picasso and Man. Retrospective 1898 -1961" and "Hommage à Pablo Picasso. Rétrospective 1895-1965" (see appendix).

3 Conclusion

These two large canvases are now considered two of Picasso's most significant works. They are currently held at two major museums in the United States. La famille de saltimbanques which had been auctioned for a record-breaking price in 1914, has not been featured in important exhibition; while Les demoiselles d'Avignon which had sold for much less in 1923 has been acclaimed as a major breakthrough and has been regularly featured in major Picasso retrospectives. One could conclude that the importance a painting may have in art history is not always matched by the price attained at sale.

Appendix

Exhibitions featuring La famille de saltimbanques.

• Picasso-Braque-Léger (Museum of French Art, New York, February, 1931). (No. 4)

• 20th Century Paintings from the Chester Dale Collection (The Art Institute of Chicago, 1954).

• The Chester Dale Bequest (National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, May 6 - August 18, 1965).

• Aspects of Twentieth-Century Art (National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, June 1, 1978 - July 30, 1979).

• Picasso, The Saltimbanques (National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, December 14, 1980 - March 15, 1981).

• Picasso: The Early Years 1892-1906 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, March 30 - July 27, 1997); The Young Picasso (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, September 10, 1997 - January 4, 1998).

• Picasso und das Theater / Picasso and the Theater (Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, October 21, 2006 - January 21, 2007).

Exhibitions featuring Les demoiselles d'Avignon.

• L'Art moderne en France (Galerie Poiret (Salon d'Antin), Paris, 16-31 July, 1916).

• Œuvres de Matisse et de Picasso (Galerie Paul Guillaume, Paris, January 23 - February 15, 1918).

• Twenty Years in the Evolution of Picasso, 1903-1923 (Jacques Seligmann & Co., Inc., New York, November 1 - 20, 1937).

• The Sources of Modern Painting (Wildenstein & Co., New York, May, 1939).

• Art in Our Time: 10th Anniversary Exhibition (The Museum of Modern Art, New York, May 10 - September 30, 1939).

• Picasso: Forty Years of His Art (Picasso, Epochs in his Art) (The Museum of Modern Art, New York, November 15, 1939 - January 7, 1940; The Art Institute of Chicago, February 1 - March 3/5, 1940; The City Art Museum of St. Louis, March 16 - April 14, 1940; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, April 26 - May 25, 1940; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, June 25 - July 22, 1940; Cincinnati Museum of Art. September 28 - October 27, 1940; Cleveland Museum of Art. November 7 - December 8, 1940); Isaac Delgado Museum, New Orleans, December 20, 1940 - January 17, 1941; Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Minneapolis, February 1 - March 2, 1941; and Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, March 15 - April 13, 1941; Munson-Williams-Proctor Insntitute, Utica, November 1-24, 1941; Duke University, Durham, November 29 - December 20, 1941; William Rockhill Nelson Art Gallery, Kansas City, January 24 - February 14, 1942; Milwaukee Art Insntitute, February 20 - March 13, 1942; Grand Rapids Art Gallery, March 23 - April 13, 1942; Dartmouth College, Hanover, April 27 - May 18, 1942; Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, May 20 - June 15, 1942; Wellesley College, Wellesley, September 27 - October 18, 1942; Sweet Briar College, Sweet Briar, October 28 - November 18, 1942; Williams College, Williamstown, November 28 - December 19, 1942; Indiana University Art Center Gallery, Bloomington, January 1-22, 1943; Monticello College, Alton, February 5-26, 1943; Portland Art Museum, Portland, April 1-30, 1943).

• Cubist and Abstract Art (The Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 25 - May 3, 1942).

• Le Cubisme, 1907-1914 (Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris, January 30 - April 9, 1953).

• Paintings From the Museum Collection: Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Exhibition (The Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 9, 1954 - January 23, 1955 (1st Floor); October 19, 1954 - January 2, 1955 (2nd Floor); October 19, 1954 - February 6, 1955 (3rd Floor)).

• Picasso: 12 Masterworks (The Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 15 - April 24, 1955).

• Picasso, 75th Anniversary (The Museum of Modern Art, New York, May 4, 22 - September 8, 1957; The Art Institute of Chicago, October 29 - December 8, 1957); Picasso: A Loan Exhibition of his Paintings, Drawings, Sculpture, Ceramics, Prints and Illustrated Books (Philadelphia Museum of Art, January 8 - February 23, 1958).

• Les Sources du XXe siècle. Les arts en Europe de 1844 à 1914 (Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris, November 4, 1960 - January 23, 1961).

• Picasso. Retrospective 1895-1959 (Tate Gallery, London, July 6 - September 18, 1960).

• Picasso and Man. Retrospective 1898 -1961 (The Art Gallery of Toronto, January 11 - February 16, 1964; Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, February 28 - March 31, 1964).

• Hommage à Pablo Picasso. Rétrospective 1895-1965 (Grand Palais, Paris (Peintures); Petit Palais, Paris (Dessins, Sculptures, Ceramiques), November 18/19/20, 1966 - February 12/28, 1967).

• The Cubist Epoch (Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Los Angeles, December 15, 1970 - February 21, 1971; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, April 7 - June 7, 1971).

• Picasso in the Collection of the Museum of Modern Art (The Museum of Modern Art, New York, January 25 / February 3 - April 2, 1972).

• Pablo Picasso: A Retrospective (The Museum of Modern Art, New York, May 22 - September 16, 1980).

• Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (Musée Picasso, Paris, January 26 -April 18,1988; Museu Picasso, Barcelona, May 10/11 - July 14, 1988).

• Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism (The Museum of Modern Art, New York, September 24 , 1989 - January 16, 1990).

• Picasso and Photography: The Dark Mirror (The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, November 16, 1997 - February, 1, 1998; München Stadtmuseum, München, March 3 - May 3, 1998; Bunkamura Museum of Art, Tokyo, June 5/6 - June 28, 1998; Suntory Museum of Art, Osaka, July 7/8 - August 23, 1998; Palazzo Vecchio, Firenze, September - November, 1998).

• Matisse Picasso (Tate Modern, London, May 11 - August 18, 2002; Les Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, September 25, 2002 – January 6, 2003; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, February 13 - May 19, 2003).

• Picasso and American Art (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 28, 2006 - January 28, 2007; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, February 25 - May 28, 2007; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, June 17 - September 9, 2007).

References

[1]. Baldassari, A., ed. (2006). The Surrealist Picasso (Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, June 12 - September 12, 2005). New York: Random House.

[2]. Bouvier, R., ed. (2019). The Early Picasso: Blue and Rose Periods. Riehen / Basel.

[3]. Bransten, E. (1944). "The significance of the clown in paintings by Daumier, Picasso and Rouault." Pacific Art Review. 3, pp. 21–39.

[4]. Cabanne, P. (1979). Pablo Picasso: His Life and Times. New York: William Morrow.

[5]. Carmean, E., Jr. (1980). Picasso, The Saltimbanques. Washington, DC: The National Gallery of Art.

[6]. Chapon, F. (1984). Mystère et splendeurs de Jacques Doucet, 1853-1929. Paris: Jean-Claude Lattès.

[7]. Choucha, N. (1992). Surrealism and the Occult: Shamanism, Magic, Alchemy, and the Birth of Artistic Movement. Rochester, VT: Destiny Books.

[8]. Cousins, J. and P. Daix. (1989). "Chronology." Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism. pp. 335–452. Ed. by William S. Rubin. New York: Museum of Modern Art Graphic Society.

[9]. Cowling, E. (2002). Picasso: Style and Meaning. London; New York: Phaidon.

[10]. Daemgen, A. (2005). "Picasso. Ein Leben." Pablo. Der private Picasso: Le Musée Picasso à Berlin. pp. 14–44. Ed. by Angela Schneider and Anke Daemgen. München: Prestel.

[11]. Daix, P. (1965). Picasso. New York: Preager.

[12]. Daix, P. (1987). Picasso, createur: la vie intime et l'oeuvre. Paris: Editions du Seuil.

[13]. Daix, P. & J. Rosselet. (1979). Picasso: The Cubist Years, 1907–1916: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings & Related Works. Neuchâtel: Ides & Calendes; Boston: New York Graphic Society. 1979.

[14]. FitzGerald, M. (1995). Making Modernism: Picasso and the Creation of the Market for Twentieth Century Art. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

[15]. Flam, J. & M. Deutch, eds. (2003). Primitivism and Twentieth-Century Art: A Documentary History. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press

[16]. Franck, D. (2001). Bohemian Paris: Picasso, Modigliani, Matisse, and the Birth of Modern Art. New York: Grove Press.

[17]. Geelhaar, C. (1993). Picasso: Wegbereiter und Förderer seines Aufstiegs 1899–1939. Zürich: Palladion / ABC Verlag.

[18]. Gilot, F. and C. Lake. (1964). Life with Picasso. New York: McGraw-Hill.

[19]. Golding, J. (1958). "The 'Demoiselles d'Avignon'." The Burlington Magazine. Vol. 100, No. 662. (May). pp. 154–163.

[20]. Golding, J. (1968). Cubism: A History and an Analysis 1907–1914. New York: Harper and Row.

[21]. Kahnweiler, D. (1949). The Rise of Cubism. New York: Wittenborn, Schultz.

[22]. Kahnweiler, D. (1971). My Galleries and Painters. New York: The Viking Press.

[23]. Karmel, P. (2007). "Le Laboratoire Central." Cubist Picasso. pp. 149–163. Ed. by Anne Baldassari. Paris: Flammarion.

[24]. Lavin, I. (2007). "Théodore Aubanel's 'Les Filles d'Avignon' and Picasso's 'Sum of Destructions.'" Picasso Cubiste / Cubist Picasso. pp. 55–69. Ed. by Anne Baldassari. Paris: Flammarion.

[25]. Léal, B., et al. (2000). The Ultimate Picasso. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

[26]. Madeline, L. (2006). Picasso and Africa. Cape Town, Bell-Roberts Publisher.

[27]. Mallen, E., ed. (2024). The Online Picasso Project Catalogue Raisonné (OPP). Sam Houston State University. http://picasso.shsu.edu.

[28]. McCully, M. (1992). "Picasso in North Holland: A Journey of Artistic Discovery." Picasso, 1905–1906. De l'època rosa als ocres de Gósol. pp. 51–62. Ed. by Maria Teresa Ocaña, Hans Christoph von Tavel, Núria Rivero, Teresa Llorens, et al. Barcelona: Electa.

[29]. O'Brian, P. (1994). Pablo Picasso. A Biography. New York: W.W. Norton and Company.

[30]. Parmelin, H. (1966). Picasso, Intimate Secrets of a Studio at Notre Dame de Vie. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

[31]. Penrose, R. (1981). Picasso: His Life and Work. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[32]. Read, P. (2011). "All Fields of Knowledge." Picasso in Paris 1900–1907: Eating Fire. pp. 155–176. Ed. by Marilyn McCully, et al. Brussels: Mercatorfonds

[33]. Reff, T. (1971). "Harlequins, Saltimbanques, Clowns and Fools." Artforum. 10. (October). pp. 30–43.

[34]. Revel, J. (1961). "Jacques Doucet, couturier et collectionneur." L'Oeil (Paris and Lausanne), no. 84 (December), pp. 44-51, 81, 106.

[35]. Richardson, J. (1991). A Life of Picasso. Volume I: The Prodigy, 1881–1906. New York: Random House.

[36]. Richardson, J. (1996). A Life of Picasso. Volume II: The Painter of Modern Life, 1907 1917. New York: Random House.

[37]. Riedel, D. (2011)."'... da war ich Maler!:' Die Ankunft in Paris." Picasso: 1905 in Paris. pp. 64–111. Ed. by Thomas Kellein and David Riedel. München: Hirmer Verlag GmbH.

[38]. Rilke, Rainer Maria. and Elaine E. Boney. 1975. "The Fifth Elegy." Duinesian Elegies, vol. 81. University of North Carolina Press, pp. 90–97.

[39]. Roe, S. (2015). In Montmartre: Picasso, Matisse and Modernism in Paris 1900–1910. New York: Penguin Press.

[40]. Stein, L. (1947). Appreciation: Painting, Poetry and Prose. New York: Crown.

[41]. Tinterow, G. and S. Stein, eds. (2010). Picasso in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

[42]. Tucker, M. (1992). Dreaming with Open Yes: The Shamanic Spirit in Twentieth Century Art and Culture. London: Aquarian/Thorson.

[43]. Uhde, W. (1938). Von Bismarck bis Picasso: Erinnerung und Bekenntnisse. Zürich: Römerhof Verlag.

[44]. Unger, M. (2018). Picasso and the Painting That Shocked the World. New York: Simon and Schuster.

[45]. Vallentin, A. (1963). Picasso. Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday and Co.

[46]. Varnedoe, K. (1996). "Picasso's Self-Portraits." Picasso and Portraiture: Representation and Transformation. pp. 111–179. New York: Museum of Modern Art.

[47]. Weiss, J. (1997). "Bohemian Nostalgia: Picasso in Villon's Paris." Picasso: The Early Years 1892–1906. pp. 197–209. Ed. by Marilyn McCully. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

[48]. Walther, I. (1993). Pablo Picasso 1881–1973: Genius of the Century. New York: Taschen.

Cite this article

Mallen,E. (2024). From Convention to Contention: La Famille de Saltimbanques and Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. Advances in Humanities Research,9,18-30.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Humanities Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Baldassari, A., ed. (2006). The Surrealist Picasso (Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, June 12 - September 12, 2005). New York: Random House.

[2]. Bouvier, R., ed. (2019). The Early Picasso: Blue and Rose Periods. Riehen / Basel.

[3]. Bransten, E. (1944). "The significance of the clown in paintings by Daumier, Picasso and Rouault." Pacific Art Review. 3, pp. 21–39.

[4]. Cabanne, P. (1979). Pablo Picasso: His Life and Times. New York: William Morrow.

[5]. Carmean, E., Jr. (1980). Picasso, The Saltimbanques. Washington, DC: The National Gallery of Art.

[6]. Chapon, F. (1984). Mystère et splendeurs de Jacques Doucet, 1853-1929. Paris: Jean-Claude Lattès.

[7]. Choucha, N. (1992). Surrealism and the Occult: Shamanism, Magic, Alchemy, and the Birth of Artistic Movement. Rochester, VT: Destiny Books.

[8]. Cousins, J. and P. Daix. (1989). "Chronology." Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism. pp. 335–452. Ed. by William S. Rubin. New York: Museum of Modern Art Graphic Society.

[9]. Cowling, E. (2002). Picasso: Style and Meaning. London; New York: Phaidon.

[10]. Daemgen, A. (2005). "Picasso. Ein Leben." Pablo. Der private Picasso: Le Musée Picasso à Berlin. pp. 14–44. Ed. by Angela Schneider and Anke Daemgen. München: Prestel.

[11]. Daix, P. (1965). Picasso. New York: Preager.

[12]. Daix, P. (1987). Picasso, createur: la vie intime et l'oeuvre. Paris: Editions du Seuil.

[13]. Daix, P. & J. Rosselet. (1979). Picasso: The Cubist Years, 1907–1916: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings & Related Works. Neuchâtel: Ides & Calendes; Boston: New York Graphic Society. 1979.

[14]. FitzGerald, M. (1995). Making Modernism: Picasso and the Creation of the Market for Twentieth Century Art. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

[15]. Flam, J. & M. Deutch, eds. (2003). Primitivism and Twentieth-Century Art: A Documentary History. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press

[16]. Franck, D. (2001). Bohemian Paris: Picasso, Modigliani, Matisse, and the Birth of Modern Art. New York: Grove Press.

[17]. Geelhaar, C. (1993). Picasso: Wegbereiter und Förderer seines Aufstiegs 1899–1939. Zürich: Palladion / ABC Verlag.

[18]. Gilot, F. and C. Lake. (1964). Life with Picasso. New York: McGraw-Hill.

[19]. Golding, J. (1958). "The 'Demoiselles d'Avignon'." The Burlington Magazine. Vol. 100, No. 662. (May). pp. 154–163.

[20]. Golding, J. (1968). Cubism: A History and an Analysis 1907–1914. New York: Harper and Row.

[21]. Kahnweiler, D. (1949). The Rise of Cubism. New York: Wittenborn, Schultz.

[22]. Kahnweiler, D. (1971). My Galleries and Painters. New York: The Viking Press.

[23]. Karmel, P. (2007). "Le Laboratoire Central." Cubist Picasso. pp. 149–163. Ed. by Anne Baldassari. Paris: Flammarion.

[24]. Lavin, I. (2007). "Théodore Aubanel's 'Les Filles d'Avignon' and Picasso's 'Sum of Destructions.'" Picasso Cubiste / Cubist Picasso. pp. 55–69. Ed. by Anne Baldassari. Paris: Flammarion.

[25]. Léal, B., et al. (2000). The Ultimate Picasso. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

[26]. Madeline, L. (2006). Picasso and Africa. Cape Town, Bell-Roberts Publisher.

[27]. Mallen, E., ed. (2024). The Online Picasso Project Catalogue Raisonné (OPP). Sam Houston State University. http://picasso.shsu.edu.

[28]. McCully, M. (1992). "Picasso in North Holland: A Journey of Artistic Discovery." Picasso, 1905–1906. De l'època rosa als ocres de Gósol. pp. 51–62. Ed. by Maria Teresa Ocaña, Hans Christoph von Tavel, Núria Rivero, Teresa Llorens, et al. Barcelona: Electa.

[29]. O'Brian, P. (1994). Pablo Picasso. A Biography. New York: W.W. Norton and Company.

[30]. Parmelin, H. (1966). Picasso, Intimate Secrets of a Studio at Notre Dame de Vie. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

[31]. Penrose, R. (1981). Picasso: His Life and Work. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[32]. Read, P. (2011). "All Fields of Knowledge." Picasso in Paris 1900–1907: Eating Fire. pp. 155–176. Ed. by Marilyn McCully, et al. Brussels: Mercatorfonds

[33]. Reff, T. (1971). "Harlequins, Saltimbanques, Clowns and Fools." Artforum. 10. (October). pp. 30–43.

[34]. Revel, J. (1961). "Jacques Doucet, couturier et collectionneur." L'Oeil (Paris and Lausanne), no. 84 (December), pp. 44-51, 81, 106.

[35]. Richardson, J. (1991). A Life of Picasso. Volume I: The Prodigy, 1881–1906. New York: Random House.

[36]. Richardson, J. (1996). A Life of Picasso. Volume II: The Painter of Modern Life, 1907 1917. New York: Random House.

[37]. Riedel, D. (2011)."'... da war ich Maler!:' Die Ankunft in Paris." Picasso: 1905 in Paris. pp. 64–111. Ed. by Thomas Kellein and David Riedel. München: Hirmer Verlag GmbH.

[38]. Rilke, Rainer Maria. and Elaine E. Boney. 1975. "The Fifth Elegy." Duinesian Elegies, vol. 81. University of North Carolina Press, pp. 90–97.

[39]. Roe, S. (2015). In Montmartre: Picasso, Matisse and Modernism in Paris 1900–1910. New York: Penguin Press.

[40]. Stein, L. (1947). Appreciation: Painting, Poetry and Prose. New York: Crown.

[41]. Tinterow, G. and S. Stein, eds. (2010). Picasso in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

[42]. Tucker, M. (1992). Dreaming with Open Yes: The Shamanic Spirit in Twentieth Century Art and Culture. London: Aquarian/Thorson.

[43]. Uhde, W. (1938). Von Bismarck bis Picasso: Erinnerung und Bekenntnisse. Zürich: Römerhof Verlag.

[44]. Unger, M. (2018). Picasso and the Painting That Shocked the World. New York: Simon and Schuster.

[45]. Vallentin, A. (1963). Picasso. Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday and Co.

[46]. Varnedoe, K. (1996). "Picasso's Self-Portraits." Picasso and Portraiture: Representation and Transformation. pp. 111–179. New York: Museum of Modern Art.

[47]. Weiss, J. (1997). "Bohemian Nostalgia: Picasso in Villon's Paris." Picasso: The Early Years 1892–1906. pp. 197–209. Ed. by Marilyn McCully. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

[48]. Walther, I. (1993). Pablo Picasso 1881–1973: Genius of the Century. New York: Taschen.