1 Introduction

As one of China’s ethnic minorities, the Tujia people have long inhabited the border regions of Hunan, Hubei, Chongqing, and Guizhou provinces. The Tujia people, with a rich history, have created a vibrant and profound culture through their diligence and perseverance over the centuries. The Tujia people have their own language, Tujia, but lack a written script, relying on oral transmission to preserve their culture. Scholars generally agree that Tujia is a unique language of the Tujia people, classified within the Sino-Tibetan language family, Tibeto-Burman branch, though its subgroup remains undetermined. Tujia is divided into southern and northern dialects, which exhibit significant differences in phonology, vocabulary, and grammar, rendering direct communication between the two dialects impossible. Throughout their long history, the Tujia people have developed cultural customs that reflect their distinct ethnic identity, such as the Baishou Dance, Weeping Wedding Songs, and Liuzi performances. Among these traditions, Sheba Songs, a work passed down through generations, serves as a cultural emblem of the Tujia people. The Tujia Sheba Songs is a collective creation of the Tujia community and is recognized as an epic that combines creation myths, heroic narratives, poetry, song, and dance. It is often described as an “encyclopedia” of Tujia culture [8], encompassing ethnographic, folkloric, epic, cultural, historical, and scientific (agriculture and handicrafts) value, and is considered a precious cultural heritage of the Tujia people [8].

Epic poetry emerges as a literary phenomenon in specific historical periods to meet the functional needs of society. Lacking early written records, Chinese ethnic minority epics primarily survive in oral form among their communities. The Tujia Sheba Songs, characterized by its reflection of ethnic historical evolution, heroic narratives, and oral transmission, qualifies as a lengthy epic. Performed entirely in the Tujia language, Sheba Songs showcases distinctive grammatical features of the language while highlighting linguistic variations across Tujia dialects. Previous studies on Sheba Songs have focused on ethnographic, cultural, historical, musical, and translational perspectives. For instance, Wu Ruishu approached Sheba Songs from an ethnographic perspective, exploring its origins, migration narratives, ethnic heroes, and “barbarian” culture, emphasizing its ethnographic value [25]. Similarly, Peng Jikuan and Yao Jipeng, in The History of Tujia Literature, conducted a detailed discussion on its artistic characteristics, literary significance, and scientific value [19]. Known also as Sheba Songs, Sheba Songs is performed during the Tujia Sheba Festival, where singing and dancing harmonize, with the songs accompanied by dances and the dances adapting to the songs. Some scholars have utilized ethnomusicological theories and methods to analyze the melodic and tonal structures of Sheba Songs. As a canonical work of China’s ethnic minorities, Sheba Songs represents an essential part of the country’s traditional culture. Its English translations contribute to the study of Tujia classics and the promotion of Chinese ethnic minority culture abroad. Shu Jing and Li Wei, using corpus-based translation studies, compared the English translation of Sheba Songs with the English versions of Ashima, translated by Dai Naidie, and the British folk epic Beowulf in modern prose. Their analysis explored lexical, syntactic, and textual features of the Sheba Songs English translation [20].

In contrast to the broader study of Sheba Songs, research on its linguistic aspects remains limited, with only Liu Ying and Xiang Liang having approached the subject from a linguistic perspective. Liu Ying, using systemic functional linguistics and the transitivity system alongside the “harmonious” eco-philosophy framework, constructed an analytical model focusing on ecological perspectives. This framework refines the participant and process type systems to examine the transitivity semantic representations and ecological philosophical implications of the intangible cultural heritage text Sheba Songs [14]. Xiang Liang, adopting a linguistic perspective, integrated textual analysis of Sheba Songs lyrics with field studies of living dialects to comprehensively explore the variations in Tujia dialects and uncover the cultural richness of the Tujia language [26]. However, research on the linguistic features of the Tujia epic Sheba Songs has largely remained at the level of semantic interpretation and lexical inquiry. Consequently, it is crucial to further investigate the epic linguistic characteristics of Sheba Songs.

Previous studies have primarily employed qualitative approaches to examine Sheba Songs, lacking support from robust linguistic data. Quantitative linguistics, as a vital branch of modern linguistics, emphasizes the use of scientific methods and tools to explain the nature, mechanisms, functions, and evolution of language. This discipline investigates various linguistic phenomena, structures, attributes, and their interrelations as observed in real communicative activities. It employs statistical and mathematical techniques such as probability theory, stochastic processes, differential equations, and functional analysis to measure, observe, model, and interpret linguistic phenomena with precision. These methods aim to uncover the hidden mathematical laws within language, depict its mathematical characteristics, and reveal the adaptive mechanisms and evolutionary dynamics of linguistic systems [11]. The concept of studying literary works through quantitative methods was first proposed by Russian literary critic and poet Michail Osipovic Lopatto. The publication of The Psycho-Biology of Language: An Introduction to Dynamic Philology by American linguist G.K. Zipf marked the formal emergence of quantitative linguistics. Zipf emphasized the use of statistical and quantitative methods to study authentic language materials, laying the foundation for contemporary quantitative linguistics. The earliest application of statistical methods to study literary works and their styles can be traced to British mathematician G. Yule. Since then, stylistic analysis based on text analysis has become a quantitative metric for identifying authorship and writing style. Previous research has shown that factors such as the frequency of nouns, pronouns, adverbs, and the type-token ratio are effective quantitative indicators for distinguishing between spoken and written registers in modern Chinese [9].

Quantitative linguistics addresses various levels of language research, including phonetics, lexicon, grammar, and text. For instance, some domestic and international scholars have attempted to examine the linguistic features of poetry from a quantitative perspective. Renowned quantitative linguist Popescu and colleagues employed quantitative methods to analyze word frequency distributions across 54 poetry texts. Building on this foundation, they used adjectives, adverbs, and verbs as quantitative indicators of descriptiveness and proactivity in poetry texts, investigating their correlational features [3]. Similarly, Liu Haitao and Pan Xiaxing applied quantitative methods to study the textual characteristics of Modern Chinese Poetry. Through cluster analysis, they identified distinctions and connections between Modern-style poetry and Modern Chinese Poetry, discovering that word frequency distribution in Modern Chinese Poetry aligns more closely with Zipf’s law. This finding underscores the “naturalness” characteristic of Modern Chinese Poetry [13]. Furthermore, Liu Haitao and Zhang Xiaojin used quantitative methods to explore the linguistic features of the Chinese folk song genre Hua’er. Through clustering experiments, they found that the word frequency distribution of Hua’er conforms to Zipf’s law. Additionally, a comparative analysis of Hua’er and May Fourth New Poetry from various levels revealed a trend toward “folk song-ization” in May Fourth New Poetry [32]. These studies demonstrate that quantitative linguistics offers a scientific and reliable new research method for poetry studies.

Sheba Songs is a long oral narrative poem passed down through the Tujia people over hundreds of thousands of years. Through this continuous transmission and refinement, fixed lyrics gradually emerged, forming a grand folk narrative poem. Investigations have revealed that no scholars have yet explored the Tujia epic Sheba Songs from a quantitative perspective. This study, based on existing Sheba Songs texts, employs common quantitative linguistics methods to analyze the quantitative features of the Tujia epic. By doing so, it aims to open a new research perspective for the study of the Tujia epic Sheba Songs.

2 Research Design

2.1 Corpus Collection and Processing

The corpus used in this study is selected from the Sheba Songs compiled, translated, and annotated by Tujia scholars Peng Bo and Peng Jikuan, under the editorial direction of the Hunan Minority Classics Office, published by Yuelu Publishing House in 1989. This text utilizes the International Phonetic Alphabet to document the phonetics of ancient Tujia songs and provides a Chinese interpretation, creating the first standardized version of Tujia oral literature. It has made a monumental contribution to the translation of minority classics. The Sheba Songs consists of four sections: songs of human origins, migration songs, agricultural labor songs, and heroic narrative songs. This epic originated in Western Hunan, where ethnic minorities constitute more than 50% of the population, and it is particularly widespread in the northwestern part of the region. From Sheba Songs (1989), 10 ancient songs were randomly selected. Additionally, 10 Modern-style poetrys and 10 Modern Chinese Poetrys were randomly chosen, along with 10 folk songs from the Anthology of Chinese Folk Songs: Hunan Volume. Table 1 provides detailed information on the corpus used in the study.

Table 1. Corpus Samples Used in the Study

Tujia Epic: Sheba Songs |

Modern-style poetry |

Modern Chinese Poetry |

Folk Songs |

|||||

No. |

Title |

No. |

Author |

Title |

No. |

Author |

Title |

No. |

1 |

Preparation for the Sheba Festival |

1 |

Li Bai |

Invitation to Wine |

1 |

Liu Ban Nong |

Falling Leaves |

1 |

2 |

Prayer for Harvest |

2 |

Bai Juyi |

The Everlasting Longing |

2 |

Lin Huiyin |

One Summer Night in the Mountains |

2 |

3 |

Hardships on the Journey |

3 |

Du Fu |

On the Height |

3 |

Wang Zuo Liang |

Long Night Walk |

3 |

4 |

Settlements Along the Journey |

4 |

Wang Wei |

Autumn Evening in the Mountains |

4 |

Mu Dan |

Winter Night |

4 |

5 |

Planting Corn |

5 |

Tao Yuanming |

Drinking Wine |

5 |

Zhou Meng Die |

October |

5 |

6 |

Transplanting Rice Seedlings |

6 |

Lu You |

A Visit to a Village West of the Mountains |

6 |

Shu Ting |

Toward the North |

6 |

7 |

Husking Rice |

7 |

Wang Bo |

Farewell to Prefect Du |

7 |

Zhang De Yi |

The Wilderness in April |

7 |

8 |

Carrying Corn Home |

8 |

Su Shi |

Drinking at the Lake, First in Sunny, Then in Rainy Weather |

8 |

Wang Yin |

Near |

8 |

9 |

Eight Brothers’ Leaving Home |

9 |

Meng Haoran |

Visiting an Old Friend’s Cottage |

9 |

Pang Pei |

Snowy Night |

9 |

10 |

Planting Winter Crops |

10 |

Zhang Jiuling |

Looking at the Moon and Longing for One Far Away |

10 |

Xie Xiangnan |

Reclamation of the Sea |

10 |

Following corpus collection, a statistical analysis of the word frequency distribution in the Tujia epic Sheba Songs was conducted to verify whether its text conforms to Zipf’s law. Using nouns, verbs, and pronouns from the texts as clustering indicators, software was employed for automated clustering. The resulting classifications were analyzed to explore the distinctions and connections between Sheba Songs, Modern-style poetry, Modern Chinese Poetry, and Chinese folk songs.

2.2 Research Questions

(1) Does the text of the Tujia epic Sheba Songs conform to Zipf’s Law?

(2) What are the connections between the textual features of the Tujia epic Sheba Songs, Modern-style poetry, and Modern Chinese Poetry?

(3) Are there stylistic similarities between the Tujia epic Sheba Songs and Chinese folk songs?

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 The “Naturalness” of the Tujia Epic Sheba Songs

Zipf’s Law describes the frequency distribution of words in a text, positing that when words are ranked in descending order of frequency, the frequency of a word is inversely proportional to its rank. The formula (1) is expressed as:

\( y=\frac{a}{x^{b}} \) (1)

Where y represents word frequency, x represents word rank, and a and b are parameters.

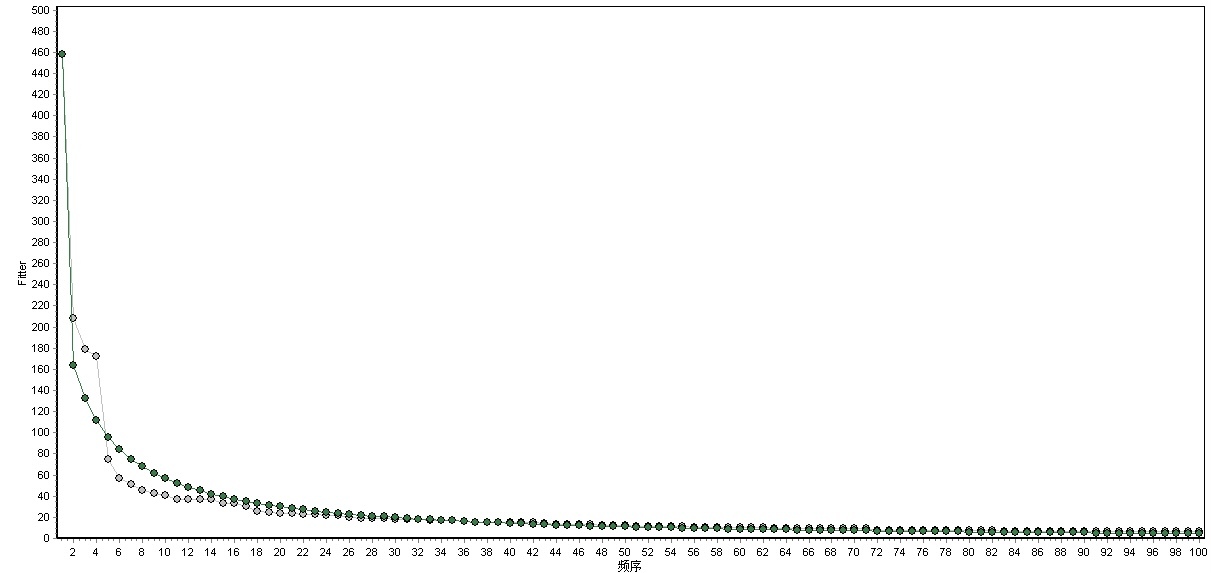

Quantitative linguistics emphasizes using authentic texts as research materials, employing statistical methods commonly used in natural sciences to enhance objectivity in linguistic studies, thereby improving the reliability of research results [11]. Frequency, one of the most frequently used metrics in quantitative linguistics, refers to the number of times a linguistic unit appears in a text. Dividing this number by the total occurrences of all linguistic units in the text yields the probability of the linguistic unit. Table 2 shows the frequency and probability sequence of the top 10 words from 10 samples of the Tujia epSic Sheba Songs, arranged in descending order. Figure 1 illustrates the frequency distribution curve of these words and the Zipf’s Law fitting curve.

Table 2. Word Frequency and Probability Sequence for 10 Samples of the Tujia Epic Sheba Songs

Rank |

Word |

Frequency |

Probability (%) |

1 |

了(le) |

458 |

57.12 |

2 |

在(zai) |

208 |

25.94 |

3 |

的(de) |

179 |

22.32 |

4 |

哩(li) |

172 |

21.45 |

5 |

着(zhe/zhao) |

75 |

9.35 |

6 |

要(yao) |

57 |

7.11 |

7 |

好(hao) |

51 |

6.36 |

8 |

做(zuo) |

45 |

5.61 |

9 |

去(qu) |

43 |

5.36 |

10 |

你(ni) |

41 |

5.11 |

Figure 1. Word Frequency Distribution Curve and Zipf’s Law Fitting for the Tujia Epic Sheba Songs

In quantitative linguistics, the goodness-of-fit indicator R2 is commonly used to determine whether a dataset conforms to a specific model or law. The fitting results of the word frequency distribution for the Tujia epic Sheba Songs and Zipf’s Law, as shown in Figure 1, indicate an R2 coefficient of 0.9598 (with R2 > 0.90) indicating an excellent fit). This demonstrates that the word frequency distribution of the Sheba Songs text conforms to Zipf’s Law. It suggests that the text achieves a balance between homogeneity and diversity in word usage, meaning the distribution of words in the Sheba Songs is neither overly concentrated nor overly dispersed, adhering to the frequency distribution pattern described by Zipf’s Law.

Since the Tujia people lack a written language, the Sheba Songs has long been transmitted through dynamic and evolving oral forms, a tradition that continues unbroken to this day. Historically, the Sheba Songs originated from labor, flourishing and taking root in the context of agricultural production. Closely associated with productive labor are farming songs, which are reflected in the Sheba Songs through descriptions of traditional agricultural activities such as planting maize, transplanting rice seedlings, and threshing grain. These activities are expressed through naturally sung forms, with the intensity of singing growing over time. Consequently, the Sheba Songs exhibits distinct collective and oral characteristics in its creation and transmission. While oral artistic creation and the text’s formalization influence the Sheba Songs, it retains its original ecological form in Tujia communities, gradually evolving into a unique literary genre rich in ethnic characteristics. The goodness-of-fit coefficient and the presence of high-frequency words both indicate that the word frequency distribution of the Sheba Songs conforms to Zipf’s Law, reflecting the text’s internal linguistic mechanism of “self-organization.”

The Sheba Songs shares similarities with Tujia proverbs, folk stories, and poetry in its origins, emerging from everyday oral traditions within the labor scenarios of the Tujia people. Its oral text does not emphasize meticulous wordsmithing but is transmitted in a free and dynamic artistic form, endowing it with exceptional vitality and literary vigor. This natural state further underscores that the word usage in the Sheba Songs adheres to Zipf’s Law.

3.2 Textual Features of the Tujia Epic Sheba Songs

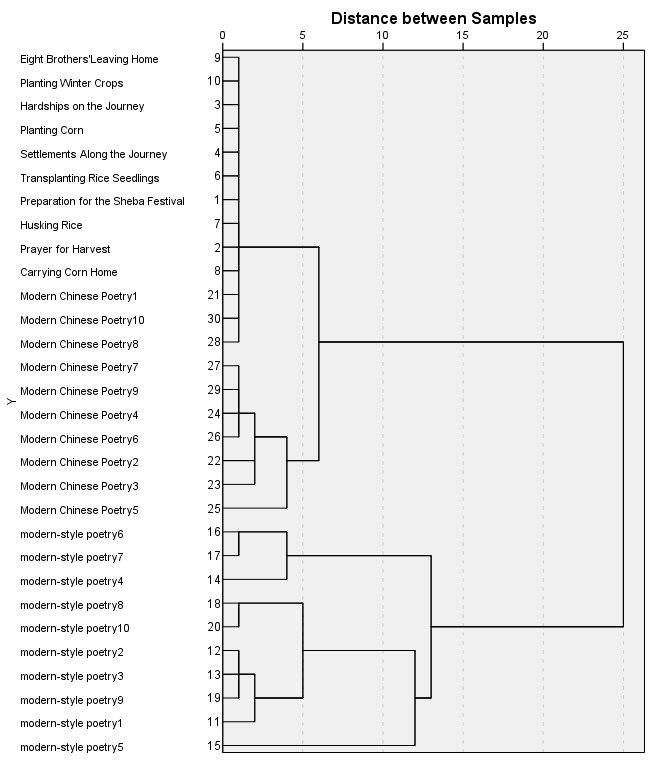

Cluster analysis is a multivariate statistical method that involves grouping collected texts by comparing the properties of each sample and categorizing those with similar characteristics into clusters. This method provides a mathematical and statistical framework to describe the most relevant linguistic features among texts. Liu Haitao and Pan Xiaxing [13] effectively validated the connection between regulated verse and modern Chinese poetry through cluster analysis. In this study, the frequency of nouns and verbs in the Sheba Songs, regulated verse, and modern Chinese poetry was used as clustering indicators to explore the relationship between the Sheba Songs and these two literary forms, as shown in Table 3. Table 3 presents the frequency statistics of nouns and verbs in the Sheba Songs, regulated verse, and modern Chinese poetry. Figure 2 illustrates the classification results obtained through cluster analysis based on the probability of nouns and verbs appearing in the texts.

Table 3. Word Frequency of Nouns and Verbs in the Sheba Songs, Regulated Verse, and Modern Chinese Poetry

ID |

Title |

Nouns |

Verbs |

1 |

Preparation for the Sheba Festival |

22 |

18 |

2 |

Prayer for Harvest |

24 |

21 |

3 |

Hardships on the Journey |

22 |

19 |

4 |

Settlements Along the Journey |

21 |

18 |

5 |

Planting Corn |

24 |

22 |

6 |

Transplanting Rice Seedlings |

19 |

21 |

7 |

Husking Rice |

22 |

27 |

8 |

Carrying Corn Home |

16 |

21 |

9 |

Eight Brothers’ Leaving Home |

18 |

27 |

10 |

Planting Winter Crops |

18 |

18 |

11 |

Invitation to Wine |

14 |

6 |

12 |

The Everlasting Longing |

30 |

25 |

13 |

On the Height |

6 |

3 |

14 |

Autumn Evening in the Mountains |

6 |

0 |

15 |

Drinking Wine |

5 |

3 |

16 |

A Visit to a Village West of the Mountains |

5 |

5 |

17 |

Farewell to Prefect Du |

5 |

1 |

18 |

Drinking at the Lake, First in Sunny, Then in Rainy Weather |

3 |

1 |

19 |

Visiting an Old Friend’s Cottage |

6 |

1 |

20 |

Looking at the Moon and Longing for One Far Away |

1 |

3 |

21 |

Falling Leaves |

4 |

4 |

22 |

One Summer Night in the Mountains |

12 |

9 |

23 |

Long Night Walk |

24 |

17 |

24 |

Winter Night |

5 |

7 |

25 |

October |

8 |

11 |

26 |

Toward the North |

16 |

10 |

27 |

The Wilderness in April |

17 |

7 |

28 |

Near |

16 |

9 |

29 |

Snowy Night |

23 |

13 |

30 |

Reclamation of the Sea |

10 |

5 |

Note: IDs 1–10 represent the Sheba Songs, IDs 11–20 represent regulated verse, and IDs 21–30 represent modern Chinese poetry.

Figure 2. Clustering Analysis Results Based on the Frequency of Nouns and Verbs in the Texts

Figure 2 presents the clustering results for the Tujia epic Sheba Songs, regulated verse, and modern Chinese poetry, derived through automatic clustering using SPSS.27, with the frequency of nouns and verbs as the clustering indicators. The figure reveals that chapters of Sheba Songs, including Eight Brothers’ Leaving Home, Planting Winter Crops, Hardships on the Journey, Planting Corn, Settlements Along the Journey, Transplanting Rice Seedlings, Preparation for the Sheba Festival, Husking Rice, Prayer for Harvest and Carrying Corn Home, are clustered alongside three modern Chinese poems: Liu Bannong’s Falling Leaves (ID 1), Wang Yin’s Near (ID 8), and Xie Xiangnan’s Reclamation of the Sea (ID 10). Furthermore, Prayer for Harvest and Carrying Corn Home exhibit closer clustering proximity to modern Chinese poems (IDs 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10) compared to regulated verse. This proximity can be attributed to the defining characteristic of modern Chinese poetry, namely its “freedom.” Modern Chinese poetry breaks away from the constraints of traditional poetic rules, adopting more flexible and diverse structures, layouts, and arrangements. Chen Aizhong has described this shift, emphasizing the “Chineseness” of modern Chinese poetry in its poetic experience and linguistic styles. The language style has undergone significant changes, favoring simplicity, naturalness, and a flexible use of colloquial, vernacular, and dialect expressions, which closely align with everyday life and oral communication. The Tujia epic Sheba Songs, having evolved through generations of oral transmission, possesses its own distinct artistic and expressive features. As a national epic, it is structurally rigorous, with interconnected yet independently cohesive sections. Its rich content spans grand creation myths, heroic tales, and songs reflecting everyday life and agricultural activities. The Compilation of Chinese Folk Songs: Hunan Volume (Part II) describes Sheba Songs as follows:

“Sheba Songs encompasses a wide range of content, including the creation of heaven and earth, long migrations , seasonal agricultural activities, and tales of characters. Its lyrics form a long narrative poem that blends mythology, history, labor, life, and human affairs. It is a masterpiece of Tujia literature, crafted across generations.”

As a paradigmatic oral tradition of the Tujia ethnic group, Sheba Songs primarily uses the ancient Tujia language in a free verse style. Although it adheres to rhythmic patterns, it is not restricted by syllable counts or strict rules, allowing for expressive and vivid narration. The frequent repetition of specific phrases or events emphasizes themes and reinforces the audience’s memory. Its lyrics are colloquial, natural, and imbued with everyday life, showcasing the free verse style prevalent in early Tujia folk songs. Singers narrate stories in conversational Tujia language, accompanied by the melodic chanting of Tima priests, creating a poetic atmosphere. For instance:

Pa55 je51 phan21 toŋ55 Pa55 je51 ye55 吧吔盘冬吧吔吔,

Pa55 je51 phan21 toŋ55 Pa55 je51 ye55 吧吔盘冬吧吔吔,

Pa55 je51 phan21 toŋ55 Pa55 je51 toŋ55 吧吔盘冬吧吔冬,

Pa55 je51 je51 phan21 toŋ55 phan21 吧吔吔盘冬盘!

Pa55 je51 je51 phan21 toŋ55 phan21 吧吔吔盘冬盘!

Pa55 je51 phan21 toŋ55 Pa55 je51 toŋ55 吧吔盘冬吧吔冬,

Pa55 je51 phan21 toŋ55 Pa55 je51 toŋ55 吧吔盘冬吧吔冬,

Pa55 je51 phan21 toŋ55 Pa55 je51 toŋ55 吧吔盘冬吧吔冬!

——《备社巴》Preparation for the Sheba Festival

ten21 toŋ21 ten21 toŋ21 oŋ21 la21 xu55 叮冬叮冬响在了,

ten21 toŋ21 ten21 toŋ21 oŋ21 la21 xu55 叮冬叮冬响在了,

li35 pu55 xa21 ma21 xa21 la21 xu55 谷子打人打在了。

ŋa51 ma51 le55 割的人哩,

se21 la21 me35 ka21 tɕhiau35 po55 la55 屁股天上翘着在,

kho55 pa51 pa21 tsi21 ka35 po51 la55 脑壳泥巴吃着在。

——《打谷子》Husking Rice

Although agricultural songs like Songs of Harvest in Sheba Songs show the influence of Han folk songs, often adopting the seven-character verse form and combining Tujia and Han languages, they maintain linguistic diversity. In terms of performance, Sheba Songs is closely integrated with dance, accompanied by drumbeats, with lyrics performed continuously without fixed chapters, adapting to the progression of the narrative. Compared to the strict stylistic requirements of regulated verse—such as tonal patterns, rhyme schemes, and antithesis—Sheba Songs exhibits stylistic traits more akin to modern Chinese poetry. Therefore, the clustering experiment using nouns and verbs as indicators highlights a certain textual similarity between the Tujia epic Sheba Songs and modern Chinese poetry in terms of literary style.

3.3 “Folk Song” Features of the Tujia Epic Sheba Songs

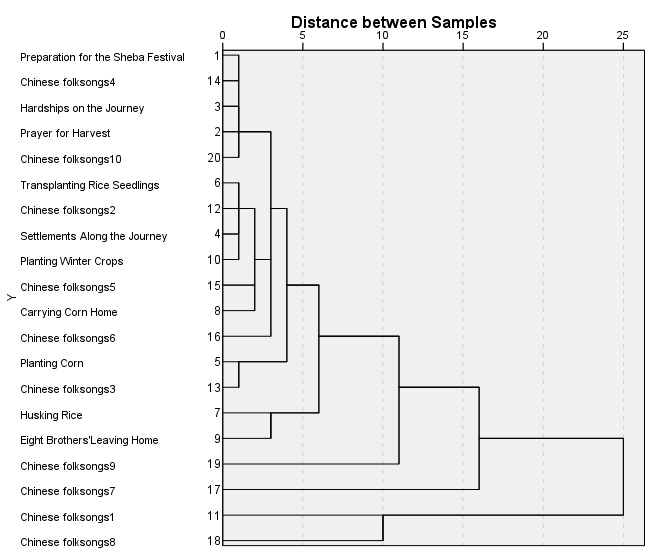

Folk songs are oral poetic creations of the working people, and their natural and simple linguistic characteristics align with the collective singing tradition of the Tujia epic Sheba Songs. Folk songs are an art of language, characterized by distinct local and ethnic features. Previous studies have shown that the word frequency distribution in Chinese folk songs, such as Hua’er, follows Zipf’s Law, and its internal linguistic structure exhibits a “self-organizing” pattern. Zhang Xiaojin, using quantitative methods, studied the linguistic features of folk songs from the Yellow River Basin and demonstrated that the vocabulary of these songs reflects the general linguistic property of “self-organization,” which can help explain both the unity and diversity of word usage in language [33]. Furthermore, from the perspective of quantitative linguistics, Zhang Xiaojin and Liu Haitao used the probability distribution of word categories in poetic texts and conducted clustering experiments to verify that the New Poetry of the May Fourth Movement exhibits colloquial features typical of folk songs [32]. The Sheba Songs is a lengthy oral poem—does its text exhibit features of a folk song? To answer this question, this paper uses the frequency of nouns, verbs, and pronouns in Sheba Songs and Chinese folk songs as clustering indicators. After automatic clustering using software, the clustering results of Sheba Songs and Chinese folk songs were obtained. Table 4 shows the frequency of nouns, verbs, and pronouns in the Tujia epic Sheba Songs and Chinese folk songs, while Figure 3 presents the results of the clustering experiment conducted using SPSS 27.0 software.

Table 4. Frequency of Nouns, Verbs, and Pronouns in the Tujia Epic Sheba Songs and Chinese Folk Songs

ID |

Title |

Nouns |

Verbs |

Pronouns |

1 |

Preparation for the Sheba Festival |

22 |

18 |

2 |

2 |

Prayer for Harvest |

24 |

21 |

2 |

3 |

Hardships on the Journey |

22 |

19 |

0 |

4 |

Settlements Along the Journey |

21 |

18 |

3 |

5 |

Planting Corn |

24 |

22 |

1 |

6 |

Transplanting Rice Seedlings |

19 |

21 |

1 |

7 |

Husking Rice |

22 |

27 |

4 |

8 |

Carrying Corn Home |

16 |

21 |

3 |

9 |

Eight Brothers’ Leaving Home |

18 |

27 |

0 |

10 |

Planting Winter Crops |

18 |

18 |

2 |

11 |

Folk Song 1 |

30 |

14 |

1 |

12 |

Folk Song 2 |

21 |

21 |

1 |

13 |

Folk Song 3 |

24 |

24 |

0 |

14 |

Folk Song 4 |

23 |

17 |

1 |

15 |

Folk Song 5 |

20 |

23 |

4 |

16 |

Folk Song 6 |

19 |

19 |

0 |

17 |

Folk Song 7 |

17 |

24 |

14 |

18 |

Folk Song 8 |

41 |

11 |

0 |

19 |

Folk Song 9 |

30 |

27 |

5 |

20 |

Folk Song 10 |

26 |

17 |

1 |

Note: ID1-10 refer to the Tujia epic Sheba Songs, and ID11-20 refer to Chinese folk songs.

Figure 3. Clustering Results Based on the Frequency of Nouns, Verbs, and Pronouns in the Texts

From Figure 3, it can be seen that by using the frequency of nouns, verbs, and pronouns in the two types of texts as clustering indicators, the clustering results reflect the close connection between the Tujia epic Sheba Songs and folk songs. The texts Preparation for the Sheba Festival, Hardships on the Journey, and Prayer for Harvest from the Tujia epic Sheba Songs are grouped together with Folk Song No. 4 and No. 10; Transplanting Rice Seedlings, Settlements Along the Journey, and Planting Winter Crops are grouped together with Folk Song No. 2; Planting Corn is grouped together with Folk Song No. 3. This can be explained as follows: firstly, the Tujia Sheba Songs originated from labor, which is indisputable. It is the crystallization of the collective wisdom of the Tujia laboring people and has existed since the fishing and hunting era. It is not the product of one specific era but has been refined and passed down through generations. Folk songs are the voices of the laboring people. The Book of Documents says: “Poetry expresses one’s aspirations, and songs echo them forever.” The earliest collection of Chinese poetry, the Book of Songs, is divided into three sections: Feng, Ya, and Song, with Feng being the most famous. Feng refers to folk songs, covering the “fifteen states” from the Yellow River Basin to the Jianghan region. Today’s Chinese folk songs, ethnic epics, and long narrative poems or lyrical poems share a distinct characteristic: they continue to live in ethnic customs and among the people, especially as folk artists still sing epics. Therefore, it is evident that the Tujia Sheba Songs is inextricably linked with folk songs. Lastly, from a literary perspective, the words and music of folk songs are inseparable. “In words, it is poetry; in music, it is song,” and songs express through “sound.” “Songs echo forever,” and the singer’s emotions are expressed through the song: the song relies on words, and words soar on the wings of melody. The song is a product of the unity of lyrics and music. Folk songs demonstrate the dual beauty of sound and meaning directly from the heart. In folk performances, poetry, song, and dance are often combined, which is one of the characteristics of folk art. This is in perfect alignment with the Tujia Sheba Songs’s recitative language and performance style.

In conclusion, by examining the relationship between the Tujia epic Sheba Songs and folk songs through nouns, verbs, and pronouns, the clustering results show that the Tujia epic Sheba Songs exhibits a tendency toward “folk-like” characteristics.

4 Conclusion

This paper preliminarily explores some common issues in the study of the Tujia epic Sheba Songs from the perspective of quantitative linguistics. From the perspective of word frequency distribution, it verifies that the frequency distribution of the Sheba Songs text highly conforms to Zipf’s Law, demonstrating the “naturalness” of the language in this orally transmitted epic, which aligns with the internal mechanisms of human language. From the perspective of text word-class probability distribution, through clustering studies, it proves that the stylistic features of the Tujia epic Sheba Songs are closer to modern Chinese new poetry, distinguishing it from the regulated verse poetry that emphasizes meticulous word and sentence construction. It also reveals that the Tujia epic Sheba Songs tends to exhibit “folk-like” characteristics. The findings of this study suggest that quantitative linguistics provides new ideas and methods for comparative studies between the Tujia epic Sheba Songs, Chinese folk songs, and other texts. This approach is expected to introduce more new quantitative methods into the study of the Tujia epic Sheba Songs and promote further in-depth research.

References

[1]. Grzybek, P. (2012). History of quantitative linguistics. Glottometrics, 23, 70–80.

[2]. Popescu, I. I., Čech, R., & Altmann, G. (2011). Vocabulary richness in Slovak poetry. Glottometrics, 22, 62–72.

[3]. Popescu, I., & Altmann, G. (2013). Descriptivity in Slovak lyrics. Glottotheory, 4, 92–104.

[4]. Yule, G. U. (1938/1939). On sentence-length as a statistical characteristic of style in prose: With application to two cases of disputed authorship. Biometrika, 30, 363–390.

[5]. Zipf, G. K. (1935). The psychobiology of language. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

[6]. Chen, D. (2012). The artistic characteristics and cultural value of the Tujia language “Sheba Songs.” Music Exploration, (04), 59–64.

[7]. Du, Y. X. (2023). The inheritance and development of Chinese folk songs. Journal of Zhejiang Art Vocational College, 21(03), 82–86.

[8]. Huang, H. (2016). A study on the epic nature of Tujia’s “Sheba Songs.” Jishou University.

[9]. Huang, W., & Liu, H. T. (2009). The application of Chinese linguistic features in text clustering. Computer Engineering and Applications, 45(29), 25–27+33.

[10]. Liu, B. Q., & Peng, L. X. (2011). Regional differences in Tujia’s Baishou dance. Journal of South-Central University for Nationalities (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition), 31(06), 55–59.

[11]. Liu, H. T., & Huang, W. (2012). The current status, theory, and methods of quantitative linguistics. Journal of Zhejiang University (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition), 42(02), 178–192.

[12]. Liu, H. T., & Lin, Y. N. (2018). Methods and trends in linguistic research in the era of big data. Journal of Xinjiang Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), 39(01), 72–83.

[13]. Liu, H. T., & Pan, X. X. (2015). The quantitative features of modern Chinese poetry. Journal of Shanxi University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), 38(02), 40–47.

[14]. Liu, Y. (2024). A study on the harmonious discourse of creation myths in intangible cultural heritage texts from the perspective of transitivity: A case study of Tujia’s “Sheba Songs.” Journal of Hunan University of Science and Technology (Social Sciences Edition), 27(03), 161–168.

[15]. Luo, X. Y., & Zeng, M. (2010). A preliminary study on the application of melody and rhythm in folk music: A case study of Tujia’s Baishou dance music. Big Stage, (02), 18–19.

[16]. Peng, B., & Peng, J. K. (Eds.). (1989). Sheba Songs (Translation). Yuelu Publishing House.

[17]. Peng, B., & Peng, J. K. (2000). Baishou activities historical materials (2nd ed.). Yuelu Publishing House.

[18]. Peng, B. (1987). A discussion on the traditional ancient songs of the Tujia ethnic group: Sheba Songs. Journal of Changsha Water Conservancy and Hydroelectric Engineering Institute (Social Sciences Edition), (03), 150–157.

[19]. Peng, J. K., & Yao, J. P. (Eds.). (1989). A history of Tujia literature. Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House.

[20]. Shu, J., & Li, W. (2021). Language features of the English translation of “Sheba Songs” based on corpus. Journal of South-Central University for Nationalities (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition), 41(04), 155–160.

[21]. Tian, K. (2010). The contemporary characteristics and functions of Tujia’s Baishou dance in Longshan, Xiangxi. Shanghai Normal University.

[22]. Tian, R. L. (2012). Protecting ethnic ancient books and preserving ethnic culture: A review and proposal for the ethnic ancient book work in Xiangxi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture. Ethnic Forum, (06).

[23]. Weng, Y. M., & Wang, J. P. (2017). A linguistic typological study on the grammatical features of the Tujia language: A case study of “Sheba Songs.” Journal of Ningxia University (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition), 39(01), 5–12.

[24]. Wu, R. S. (2007). A comparative study of “Sheba Songs” and “Ancient Words.” Journal of Hunan University (Social Sciences Edition), (01), 72–78.

[25]. Wu, R. S. (2003). The ethnological value of the epic “Sheba Songs”: A study of Tujia’s “Baishou” (Part 1). Journal of Hunan University (Social Sciences Edition), (05), 3–8.

[26]. Xiang, L. (2021). A linguistic study on the lyrics of Tujia’s Sheba Songs. Journal of Chongqing Three Gorges University, 37(02), 117–128.

[27]. Yang, D. L. (2022). On the translation aesthetic features of the English translation of Tujia ethnic classics: A case study of “Sheba Songs.” Chinese Character Culture, (15), 141–144.

[28]. Yang, Y. (2018). The major ancient books of the Tujia ethnic group and their cultural studies. Wuhan University Press.

[29]. Yin, H. B. (2009). The connotation and characteristics of oral traditional epics. Henan Education Institute Journal (Social Sciences Edition), (03).

[30]. Yin, H. B. (2009). Thirty years of research on Chinese minority epics. Journal of the Graduate School of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, (05).

[31]. Zhang, J. (2014). A narrative study of the Tujia epic “Sheba Songs.” Shaanxi Normal University.

[32]. Zhang, X. J., & Liu, H. T. (2017). The quantitative features of Chinese folk song “Hua’er.” Journal of Ningxia University (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition), 39(05), 76–80+91.

[33]. Zhang, X. J., & Liu, H. T. (2024). A quantitative study of the linguistic features of folk songs in the Yellow River Basin under the perspective of the Chinese national community. Journal of Northern Nationalities University, (02), 111–119.

[34]. Zhang, Y. M. (2020). A review and development of research on Tujia folk songs. Journal of Ganzhou Normal University, 41(04), 63–68.

Cite this article

Xiang,Y. (2024). A Quantitative Study on the Linguistic Features of the Tujia Epic Sheba Songs. Advances in Humanities Research,10,43-52.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Humanities Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Grzybek, P. (2012). History of quantitative linguistics. Glottometrics, 23, 70–80.

[2]. Popescu, I. I., Čech, R., & Altmann, G. (2011). Vocabulary richness in Slovak poetry. Glottometrics, 22, 62–72.

[3]. Popescu, I., & Altmann, G. (2013). Descriptivity in Slovak lyrics. Glottotheory, 4, 92–104.

[4]. Yule, G. U. (1938/1939). On sentence-length as a statistical characteristic of style in prose: With application to two cases of disputed authorship. Biometrika, 30, 363–390.

[5]. Zipf, G. K. (1935). The psychobiology of language. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

[6]. Chen, D. (2012). The artistic characteristics and cultural value of the Tujia language “Sheba Songs.” Music Exploration, (04), 59–64.

[7]. Du, Y. X. (2023). The inheritance and development of Chinese folk songs. Journal of Zhejiang Art Vocational College, 21(03), 82–86.

[8]. Huang, H. (2016). A study on the epic nature of Tujia’s “Sheba Songs.” Jishou University.

[9]. Huang, W., & Liu, H. T. (2009). The application of Chinese linguistic features in text clustering. Computer Engineering and Applications, 45(29), 25–27+33.

[10]. Liu, B. Q., & Peng, L. X. (2011). Regional differences in Tujia’s Baishou dance. Journal of South-Central University for Nationalities (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition), 31(06), 55–59.

[11]. Liu, H. T., & Huang, W. (2012). The current status, theory, and methods of quantitative linguistics. Journal of Zhejiang University (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition), 42(02), 178–192.

[12]. Liu, H. T., & Lin, Y. N. (2018). Methods and trends in linguistic research in the era of big data. Journal of Xinjiang Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), 39(01), 72–83.

[13]. Liu, H. T., & Pan, X. X. (2015). The quantitative features of modern Chinese poetry. Journal of Shanxi University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), 38(02), 40–47.

[14]. Liu, Y. (2024). A study on the harmonious discourse of creation myths in intangible cultural heritage texts from the perspective of transitivity: A case study of Tujia’s “Sheba Songs.” Journal of Hunan University of Science and Technology (Social Sciences Edition), 27(03), 161–168.

[15]. Luo, X. Y., & Zeng, M. (2010). A preliminary study on the application of melody and rhythm in folk music: A case study of Tujia’s Baishou dance music. Big Stage, (02), 18–19.

[16]. Peng, B., & Peng, J. K. (Eds.). (1989). Sheba Songs (Translation). Yuelu Publishing House.

[17]. Peng, B., & Peng, J. K. (2000). Baishou activities historical materials (2nd ed.). Yuelu Publishing House.

[18]. Peng, B. (1987). A discussion on the traditional ancient songs of the Tujia ethnic group: Sheba Songs. Journal of Changsha Water Conservancy and Hydroelectric Engineering Institute (Social Sciences Edition), (03), 150–157.

[19]. Peng, J. K., & Yao, J. P. (Eds.). (1989). A history of Tujia literature. Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House.

[20]. Shu, J., & Li, W. (2021). Language features of the English translation of “Sheba Songs” based on corpus. Journal of South-Central University for Nationalities (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition), 41(04), 155–160.

[21]. Tian, K. (2010). The contemporary characteristics and functions of Tujia’s Baishou dance in Longshan, Xiangxi. Shanghai Normal University.

[22]. Tian, R. L. (2012). Protecting ethnic ancient books and preserving ethnic culture: A review and proposal for the ethnic ancient book work in Xiangxi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture. Ethnic Forum, (06).

[23]. Weng, Y. M., & Wang, J. P. (2017). A linguistic typological study on the grammatical features of the Tujia language: A case study of “Sheba Songs.” Journal of Ningxia University (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition), 39(01), 5–12.

[24]. Wu, R. S. (2007). A comparative study of “Sheba Songs” and “Ancient Words.” Journal of Hunan University (Social Sciences Edition), (01), 72–78.

[25]. Wu, R. S. (2003). The ethnological value of the epic “Sheba Songs”: A study of Tujia’s “Baishou” (Part 1). Journal of Hunan University (Social Sciences Edition), (05), 3–8.

[26]. Xiang, L. (2021). A linguistic study on the lyrics of Tujia’s Sheba Songs. Journal of Chongqing Three Gorges University, 37(02), 117–128.

[27]. Yang, D. L. (2022). On the translation aesthetic features of the English translation of Tujia ethnic classics: A case study of “Sheba Songs.” Chinese Character Culture, (15), 141–144.

[28]. Yang, Y. (2018). The major ancient books of the Tujia ethnic group and their cultural studies. Wuhan University Press.

[29]. Yin, H. B. (2009). The connotation and characteristics of oral traditional epics. Henan Education Institute Journal (Social Sciences Edition), (03).

[30]. Yin, H. B. (2009). Thirty years of research on Chinese minority epics. Journal of the Graduate School of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, (05).

[31]. Zhang, J. (2014). A narrative study of the Tujia epic “Sheba Songs.” Shaanxi Normal University.

[32]. Zhang, X. J., & Liu, H. T. (2017). The quantitative features of Chinese folk song “Hua’er.” Journal of Ningxia University (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition), 39(05), 76–80+91.

[33]. Zhang, X. J., & Liu, H. T. (2024). A quantitative study of the linguistic features of folk songs in the Yellow River Basin under the perspective of the Chinese national community. Journal of Northern Nationalities University, (02), 111–119.

[34]. Zhang, Y. M. (2020). A review and development of research on Tujia folk songs. Journal of Ganzhou Normal University, 41(04), 63–68.