1. Introduction

1.1. Background

I naturally referred to the Fusuijing Building as the "People's Commune Building" and the "Communist Mansion" during my interviews with the original residents, their reactions revealed unfamiliarity and even denial. Over the past few decades, they have simply called it "the building." Listening to their oral histories of Fusuijing Building residents has shown me a different picture, a Fusuijing Building within the collective memory of the residents. These voices and recollections should be part of history that has been transformed into the building body, yet they remain overlooked and marginalized by both society and historical discourse. When we study historical buildings, we should pay more attention to voices like these.

Following the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, under the background of "learning comprehensively from the Soviet Union" [1] and the urban People's Commune movement, Changru Zhang designed the Fusuijing Building from 1958 to 1960, in northwest Beijing, now at No. 1, Santiao, White Dagoba Temple Palace Gate, Xicheng District. Today, the building carries the collective memory of two generations and serves as a microcosm of China’s societal transformations. In the collective memory of society, the Fusuijing Building is also known as the "People's Commune Building" or the "Communist Mansion."

This project examines the architectural space and daily life of the Fusuijing Building through the collective memories of its original residents. It relies on oral history and personal narratives to amplify voices that have been marginalized or forgotten [2]. In practice, it is not only about listening to and recording the stories of the original residents but also about using collective memory as a research tool and method. Through visual analysis, oral history interviews, and direct collaboration with the original residents, the collective memory of the Fusuijing Building's original residents is reconstructed, analyzed, and restored within an architectural context based on the original design archives. From both architectural and non-architectural perspectives, the descriptions of daily life and architectural space in different periods from the collective memories of the original residents are reinterpreted through speculative architectural drawings. By employing diverse forms of documentation and translation, the residents' own memory stories of the Fusuijing Building are carried out in visual and spatial representations.

1.2. Research Gap

There is limited research on the Fusuijing Building. Jian Shi compared it to the "Unité d'habitation, Marseille [3]" in Beijing in his research (Shi, 2016), which was limited to explore design archives and design background, focusing only on the spatial study of the building's early years (Hara, 2016). In Parkour in Beijing: Observations of 18 Areas, a brief interview with a resident of the Fusuijing Building provides a cursory account of its current state (Yi Shi,2009).

Over the 45 years between the building's completion and the relocation of its residents, scholars have primarily examined the Fusuijing Building as a "Communist Mansion" and "People's Commune Building" only when it was just completed. However, this utopian lifestyle lasted just over a year before it "disappeared" in 1961 due to political transformation. The stories of the building in the following 43 years seem to have been overlooked by scholars and seldom documented in existing documents, and the limited mention is brief and general, lacking depth. Currently, no detailed research has been conducted on this forgotten and marginalized history. This research seeks to address this gap by reconstructing the Fusuijing Building as remembered by its original residents, offering a nuanced perspective that extends beyond its initial ideological froming.

1.3. Significance Claim

The Fusuijing Building is recognized as one of the most representative projects in China’s architectural history, largely due to its association with the People's Commune movement (1958-1984). This research aims to offer a grassroots perspective on the Fusuijing Building, highlighting its overlooked and decentralized aspects within architectural discourse. As many first-generation residents are now aging, their memories and voices risk being lost. However, the term "Communist Mansion" encapsulates the building’s historical layers and the community memories of the Fusuijing Building. Through oral history interviews and the analysis of old photographs, I have collected the collective memories of the residents over 45 years, extracting the stories and micro-histories of the Fusuijing Building from their narratives. Using textual analysis and imaginative speculative architectural drawings, I aim to reconstruct the symbolic representation and connect the architectural space to daily life from the past to the present through the memorial manner of visualization and spatialization.

1.4. Structure of the Thesis

The thesis is structured into two main sections. The first section focuses on the design and historical background of the Fusuijing Building, as well as the vision underlying its creation. The second section outlines the research methodology and explores the Fusuijing Building within the collective memory of the residents.

2. A Social Vision

2.1. What is Communist Architecture

After the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, a movement to "comprehensively learn from the Soviet Union" (In the 1950s (1949-1956), the newly founded People's Republic of China implemented a "leaning to one side" foreign policy and launched a nationwide mass movement to comprehensively study the advanced experiences of the Soviet Union.) was launched to put Marxist materialism into practice. In August 1958, the Political Bureau of the Central Committee held an expanded meeting in Beidaihe, where the "Resolution on the Establishment of Rural People's Communes" was passed (On August 29, 1958, the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) passed a resolution on the establishment of people's communes in rural areas during the Beidaihe Conference.), sparking a nationwide surge in the people's commune movement. In December 1958, at the sixth plenary session of the 8th CPC Central Committee in Wuchang, Hubei Province. The "Resolution on Several Issues of the People's Commune" was passed. This resolution stated that the people's commune should serve as tools for transforming old cities and building socialist new cities [4]. Amidst the public's discussions on "What is the lifestyle of communism like?", people's visions for a new life formed strong social aspirations. In his memoir, writer Tiesheng Shi recalled his elementary school teacher's imagination of life in the People's Commune Building, even before its construction:

“Inside there, it truly is ‘upstairs and downstairs with electric lights and telephones,’ with gas, heating, and elevators; people living there don’t need to cook for themselves, they just go to the canteen after work and eat whatever they want; there’s a club where people can play chess, cards, and exercise during their leisure time; there’s a cinema showing movies every night, a library, public baths, medical stations, and a small shop... In short, the building is a miniature ideal society or model, where people are all like one big family, almost reaching communism. Gradually, people there won’t even need money. Why? Because it’s useless. Think about it, if you’re hungry, you go to the canteen to eat; if you’re cold, someone will make clothes and send them to you; all daily necessities are like that — need something? Just reach out and take it. [5]”(Shi, 2002)

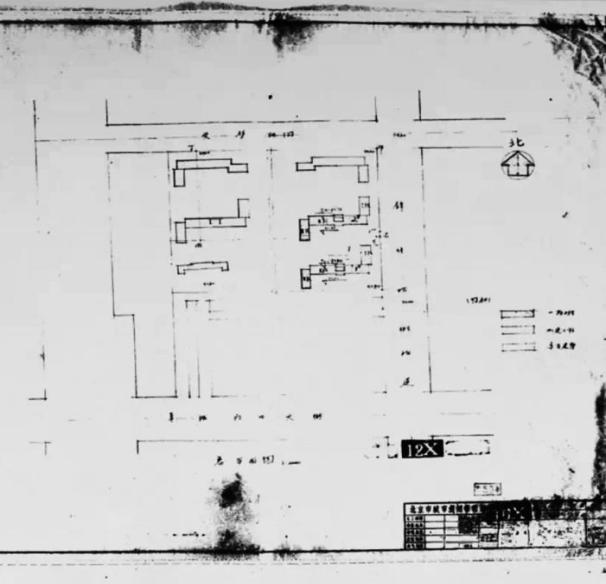

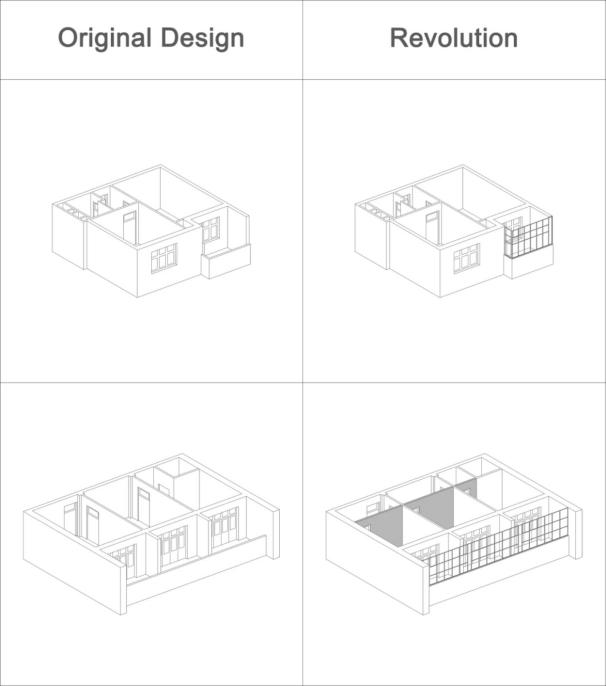

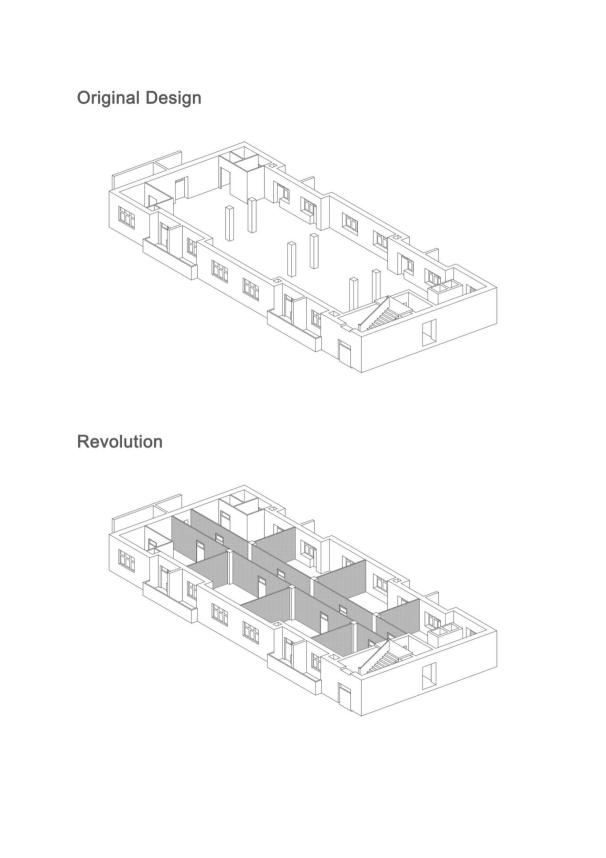

Amidst such enthusiastic discussions, in a small office of the Beijing Planning and Management Design Bureau (now the Beijing Institute of Architectural Design), 32-year-old engineer Cheng Jin and several colleagues pored over the documents from the 8th CPC Central Committee’s sixth plenary session, debating “What kind of architecture does communism need?(Lin. 2011) [6]” Under the unified social vision at that time (i.e., the socialization of housework [7]), they were tasked with coming up with initial designs for four model buildings for communism [8]. As the prototype for the design of the Fusuijing Building (originally named: Lu Xun Hall North Residence), the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China issued the Directive on Urban People's Communes in 1960, urging regions across the country to actively establish urban people's communes. The design prototype for these communist model buildings was assigned to Changru Zhang, head of Room 2 at the Beijing Planning and Design Institute, which was responsible for urban residential design. Upon reviewing the initial design, Zhang discovered that the U-shaped design of the Fusuijing Building had lighting issues, so he extended Section III southward rather than northward, resulting in the final Z-shaped design (Fig 1). (Mao,2018) [9] Kaiji Zhang, then director of the design office, also played a pivotal role in modifying the original design (Shi, 2016) [10].

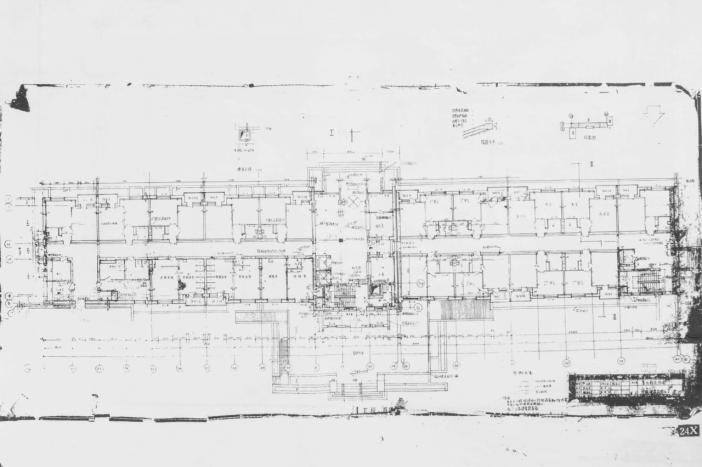

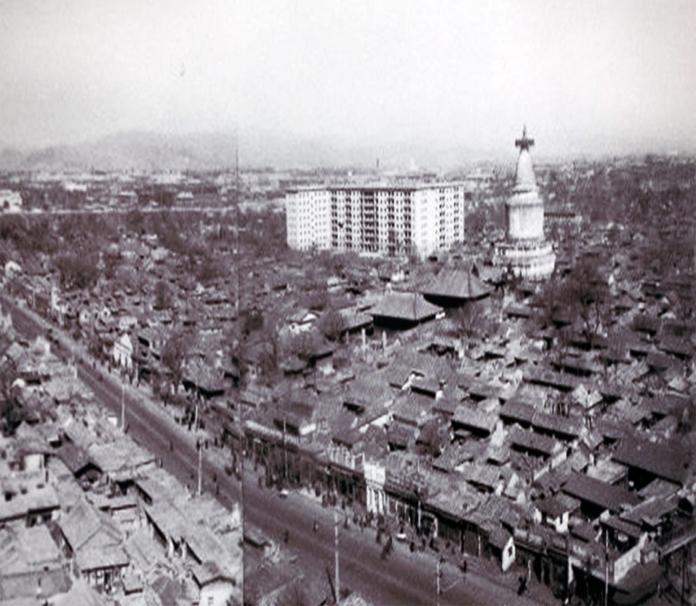

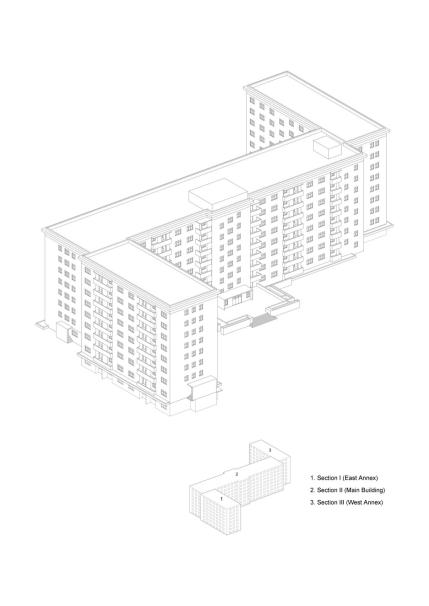

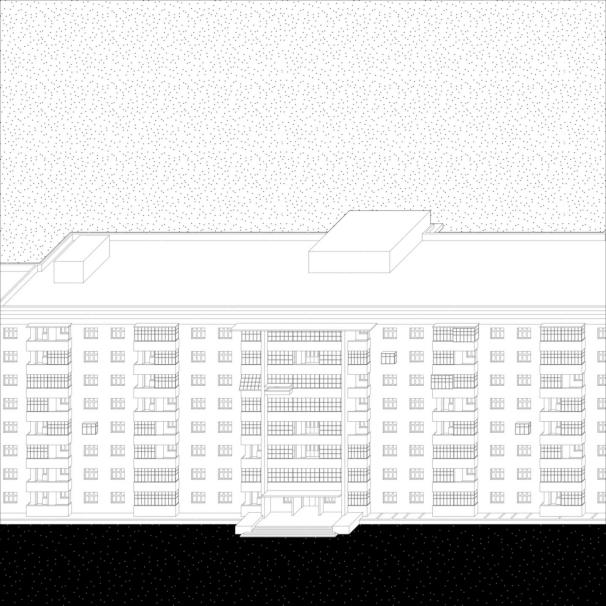

Within a year, several commune buildings completed their design plans, modifications to construction drawings (Fig 2), and construction, all utilizing brick-concrete structures. The Fusuijing Building became the most fully functional of the three model buildings (Fig 3) [11], standing in the northwest of Beijing, towering like a castle over the flat hutong neighborhood, with eight floors (Fig 4-5).

Historical materialism [12], the dominant philosophy in China at the time, asserts that the masses are the creators of history. From this perspective, the Fusuijing Building was designed as spatial representation of the ideal living style and commune structure envisioned by the time. This vision effectively made the design of the Fusuijing Building a collective act, rather than the work of an individual will. The architect, Changru Zhang, played the role of materializing the will of the people, which is why there is limited information available about him.

|

|

Figure 1. Zhang, Changru. Architectural Layout and Planning of Fusuijing Building. 1960. | Figure 2. Zhang, Changru. Original Design Archives of Section II Frist Floor Plan of the Fusuijing Building, 1960. |

|

|

Figure 3. Author. Analysis of the Locations of the Four People's Commune Buildings, 2024. | Figure 4. Unknown. Aerial View of the Fusuijing Building. Date unknown. Photograph. |

| |

Figure 5. Unknown. Fusuijing Building. Date unknown. | |

2.2. Living Together in the Fusuijing Building

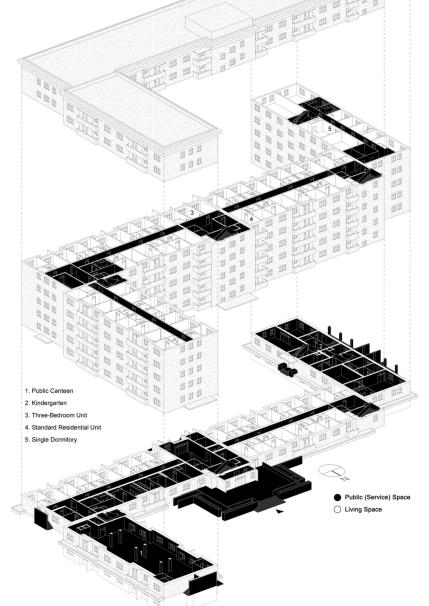

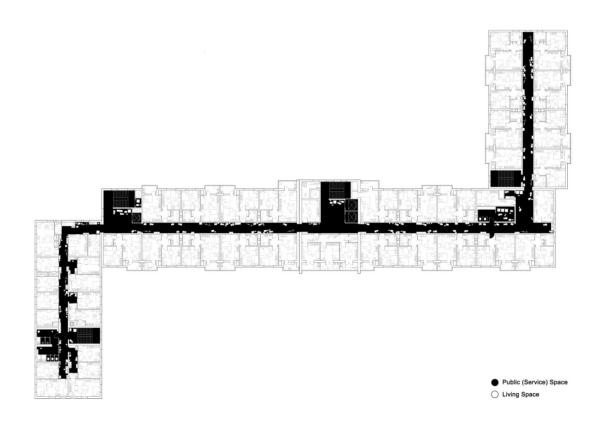

The Fusuijing Building is designed for the development of the People's Commune, with a clear social vision from top to bottom, encapsulating the manifesto: "Communism is heaven, and the People's Commune is the bridge." (Slogans of the people during the Great Leap Forward period.) The total building area is 25,000 square meters, and its design features a "Z" (Fig 6) composed of Section I (East Annex), Section II (Main Building), and Section III (West Annex). All sections are connected by a two-meter-wide long corridor (Fig 7-8). The basement of Section I houses a public kitchen, while the first-floor functions as a public canteen, while the standard floors (second to eighth floors) are residential spaces. Section II’s ground floor combines public services and residential spaces, including a small shop, public toilets, public kitchens, a hot water service room, a health clinic, a barber shop, men's changing rooms and showers, women's changing rooms and showers, and three elevators. The standard floors include storage rooms, public toilets, public kitchens, hot water rooms, 18 standard residential units (approximately 46 sqm), and one three-bedroom unit (approximately 57 sqm). The basement of Section III houses the kindergarten kitchen, the first to third floors are for the kindergarten, and the standard floors (fourth to eighth floors) are single dormitories, each floor with 15 rooms (all rooms without toilets, kitchens, or balconies), public toilets, bathrooms, storage rooms, and hot water rooms. The architect believed that families did not need to cook, as the commune canteen would replaces individual kitchens, fostering a more modern lifestyle. The single dormitories on the standard floors of Section III cater to the single status of some residents, and after marriage, they can move into the family residential units in Sections I and II. Beyond the accommodational constituents, public and social sectors are as well-equipped in the building, and the next generation is enabled to receive education after kindergarten inside it. The various public service spaces transform the Fusuijing Building into a vertical community— a small society where residents could meet most of their daily needs without leaving the building for several days. These endeavors on shared space and public functions featured the Fusuijing residential Building a multi-functional complex and marked as a Beijing Unité d'Habitation by scholar. (Shi, 2016).

|

|

|

Figure 6. Author. Redrawing the Fusuijing Building Based on Original Design Archives, 2024. Architectural Drawing | Figure 7. Author. Exploded View of the Fusuijing Building Redrawn Based on Original Design Archives, 2024. Architectural Drawing | Figure 8. Unknown. Corridor of the Fusuijing Building, 2016. Photograph. Obtained from Yi Fu |

Under the material conditions of that time, the Fusuijing Building undoubtedly provided a perfect answer to the question "What kind of architecture does communism need?" The innovation was not found in the architectural form itself but in the attempt to transform everyday life through architectural space, aligning it with a communist model. This approach is closely tied to the public life experiments derived from the social condenser theory following the 1917 Russian Revolution, which aimed to break traditional family units in urban communes by minimizing private spaces and maximizing shared public spaces, such as transforming private kitchens into communal ones and incorporating educational and medical services with residential complexes (Willimott, 2017) [13]. Under the slogan "Comprehensive Learning from the Soviet Union," the Fusuijing Building can be seen as a direct experiment in applying the social condenser theory in China.

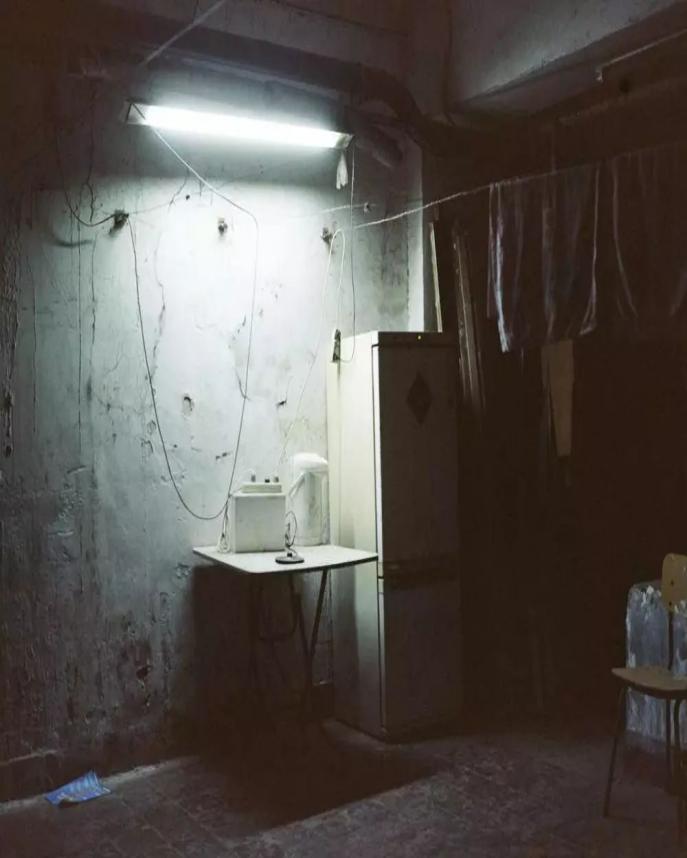

Forty-five years after its completion (Fig 9), the Fusuijing Building was evacuated in 2005 due to fire hazards, although a few households still insist on living there (Fig 10). In 2007, the building was designated as an excellent example of modern and contemporary architectural heritage by the Beijing municipal bureau of Urban Planning and the Municipal Administration of Cultural Heritage under the statement: "The Fusuijing Building, built during the period of the People's Commune, is an exploration by urban builders after the founding of the People's Republic of China to solve social issues with architectural ideals, reflecting the pursuit of communist ideals at the time and bearing the collective memory of past years. It holds significant historical value and meaning in social construction, cultural thought, national spirit, and historical research (Ruihua et al.,2018) [14]."

|

|

Figure 9. Author. Fusuijing Building and Hutong, 2024. Photograph. | Figure 10. Li, Wei. Dining Table and Refrigerator in the Dimly Lit Corridor of the Fusuijing Building, 2019. Photograph. |

3. Fusuijing Building in Collective Memory

3.1. Introduction

This section focuses on collaboration with the residents. Through interviews, the author has reconstructed the original design archives of the Fusuijing Building, illustrating the spatial layout of the building as recalled in the collective memory of its original residents.

Due to limited access to official archives in China, the author was unable to obtain primary documents. Instead, archival materials related to the Fusuijing Building were gathered through informal channels, including scanned copies of documents shared on the internet and social media, as well as illustrations published by scholars who have studied the building. While the materials were collected comprehensively, some documents-specifically those related to the kindergarten kitchen located on the underground floor of Section III (the Wset Annex)- were unavailable.

3.2. Collective Memory as Method

In 1925, Maurice Halbwachs systematically introduced the concept of collective memory as both a process and an outcome of shared past experiences within a social group, and emphasized the crucial role of social frameworks in shaping collective memory (Halbwachs, 1975) [15]. Later, in his 1950 book The Collective Memory, he expanded this concept beyond psychology, framing it within a sociological perspective, that underscores its inherently social and cultural dimensions (Halbwachs, 1992) [16]. In 1966, Aldo Rossi combined architecture with collective memory, pointing out that architecture is not only a physical structure but also a carrier and container of collective memory, embodying past narratives and historical events (Halbwachs, 2002) [17]. As a historical structure, the Fusuijing Building functions as such a repository, connecting past and present, individuals and social transformations, while encapsulating a unique architectural and historical narrative.

Completed in 1960, the Fusuijing Building was initially envisioned as a moder for "Communist life." However, the 43-years history of its everyday use remains largely undocumented if official records. To recover these untold stories, this study employs collective memory as both a theoretical framework and a research method, facilitating an exploration of the building’s lived experiences and social significance.

This research method encompasses several key aspects. Since most of the original residents of the Fusuijing Building relocated in 2005, I first conducted oral history interviews with former residents and visually analyzed old photographs they shared. Given that many residents are now elderly and some memories are blurred, I tried to help them recall stories of the Fusuijing Building through four significant historical milestones (the completion of the Fusuijing Building; the three years of economic difficulties [18]; the Cultural Revolution [19]; and the Reform and Opening-up [20]) to collect local and folk histories that had previously gone undocumented. Following this, in collaboration with the former residents, I overlaid tracing paper on the original design archives for memory-based redrawing and modification, attempting to identify the space in their memories as well as locate and map the memories in the Fusuijing Building. Finally, based on these reconstructed archives, from the perspectives of architects, I employed speculative imagination methods to reinterpret and reassemble the architectural space, daily life, and stories of the Fusuijing Building from the collective memory of its residents into creation drawings.

3.3. Fusuijing Building in Collective Memory

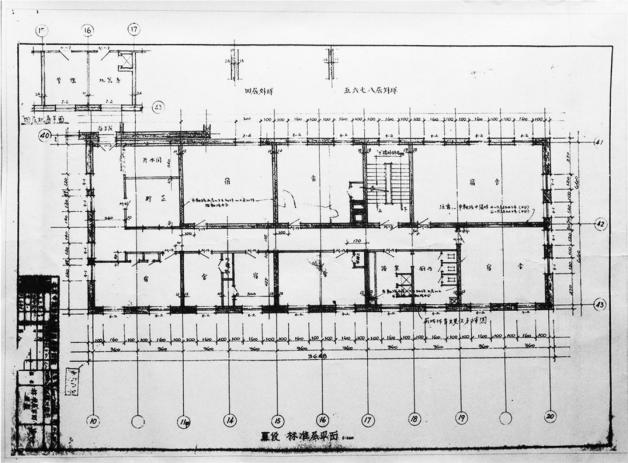

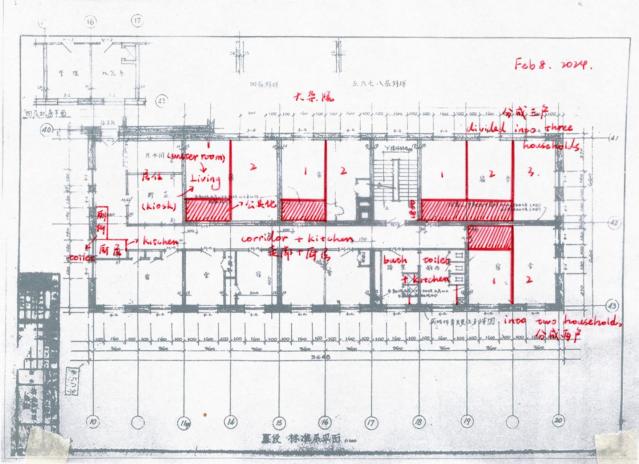

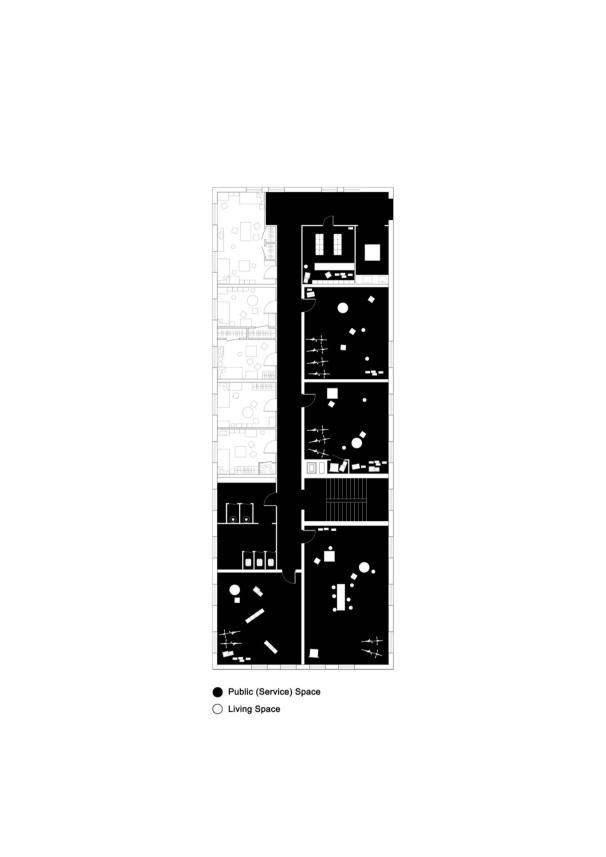

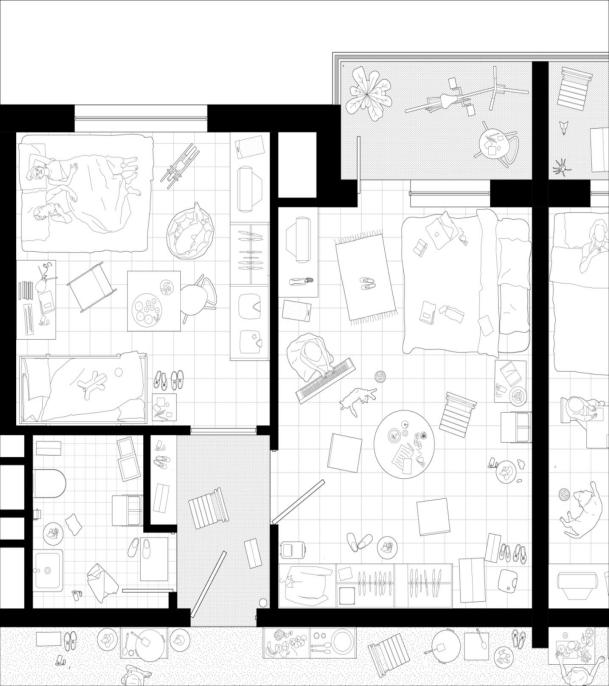

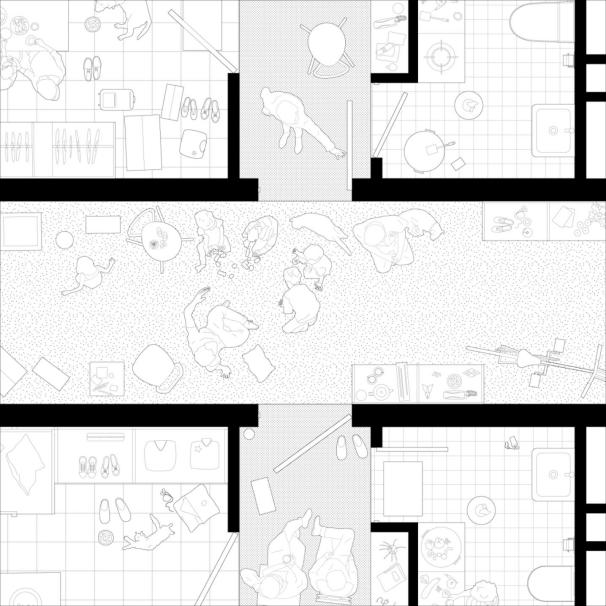

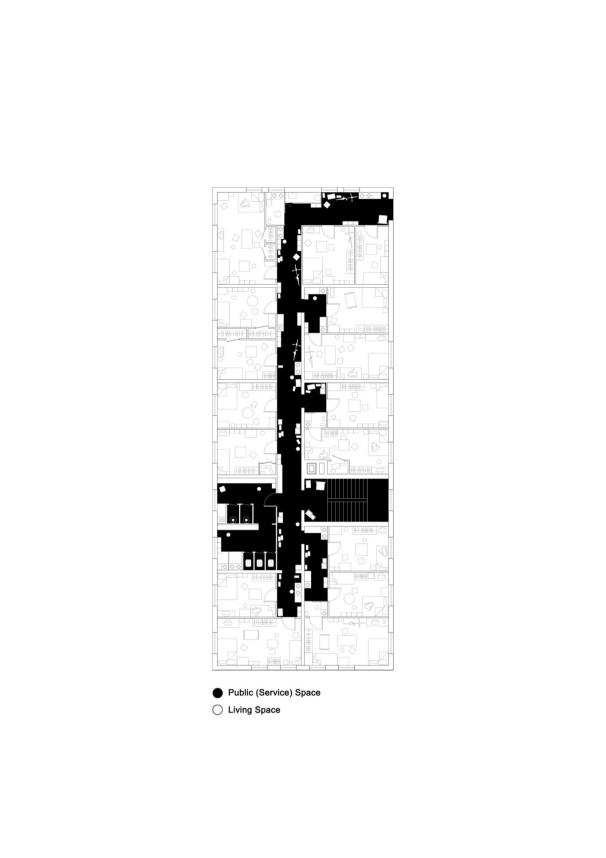

In this chapter, my practice, from an architectural perspective, involves speculative imagination based on the actual architectural space. During the interviews, I guided residents to recall their use of the Fusuijing Building's architectural space. Simultaneously, I overlaid tracing paper onto the original design archives, modifying and reconstructing them to transform the original architectural records (Fig 11) into spatial archives of residents' collective memory (Fig 12). In cases of disputed physical space memories, I used historical photographs of the Fusuijing Building to assist residents recall and facilitate discussions among multiple opinions collectively to coordinate a most convincing conclusion. Finally, drawing from the oral history interviews and spatial memory archives, I performed speculative imaginative redrawing to reconstruct the spatial form, using architectural language to represent the Fusuijing Building upon the residents' collective memory.

|

|

Figure 11. Zhang, Changru. Original Design Archives of Section III Standard Floor Plan of the Fusuijing Building, 1960. | Figure 12. Author. Speculative Floor Plan of the Standard Section III of the Fusuijing Building in Collective Memory. Interviewees: Hanran Zhang, Shuo Yu, Lanping Xu, and Yehang Yu. |

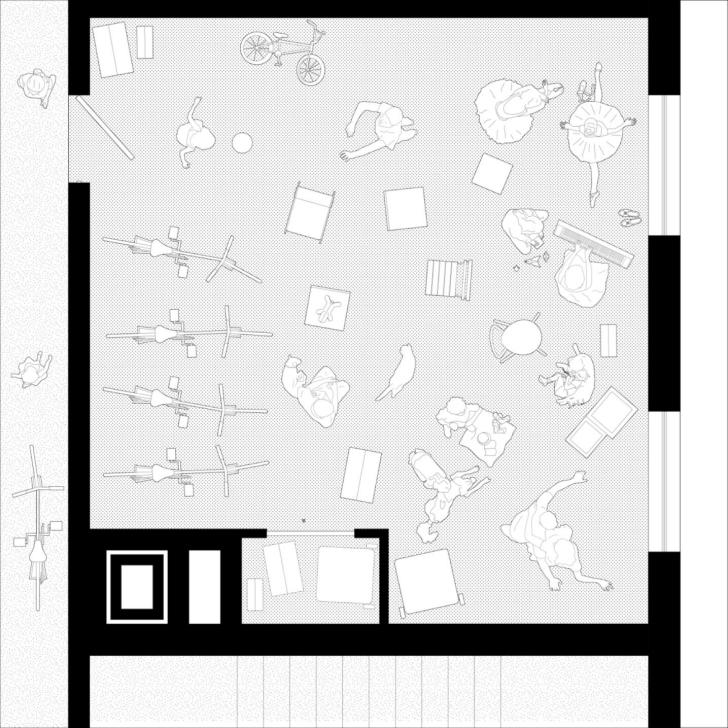

Unlike the Fusuijing Building, as a symbol of "communism," a more "tangible and lived" Fusuijing Building was reconstructed based on local knowledge and experience. In the minds of former residents, the Fusuijing Building was actually a public rental housing, where tenants were required to pay rent monthly. Due to the welfare housing system [21] adopted by the country at that time, everyone living in the Fusuijing Building held a certain social status or had made contributions to the country (a kind of qualification). As a result, many rooms in the building remained unoccupied and were spontaneously transformed into public activity rooms by the residents (Fig 13-14). The kindergarten within the building did not exclusively serve residents, and some residents' children were not even eligible to attend. The highly anticipated public canteen charged relatively high meal prices, making many residents reluctant to dine there. Despite these many discrepancies from the ideal, the building did foster a small-scale collectivist society in the first year after its completion, living an ideal socialist life.

|

|

Figure 13. Author. Speculated Floor Plans of Standard Section III of the Fusuijing Building in Collective Memory from 1960-1962, 2024. Speculative Architectural Drawing. | Figure 14. Author. Renovating a Spare Room into an Activity Room, 2024. Speculative Architectural Drawing. |

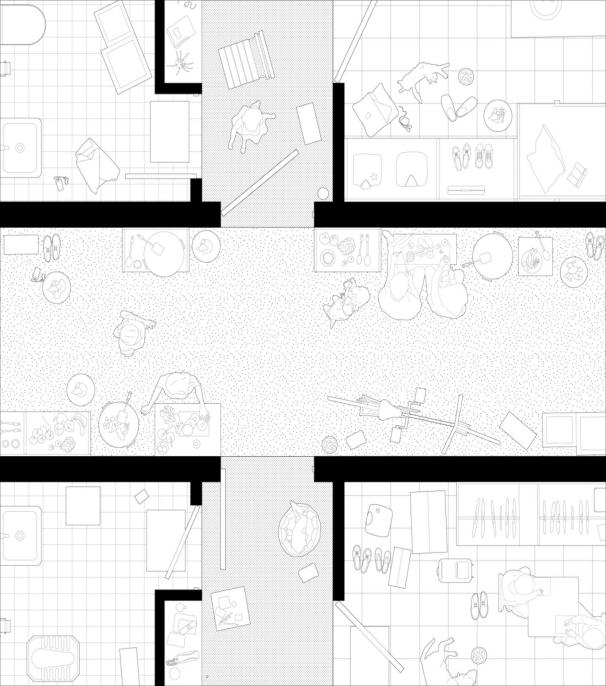

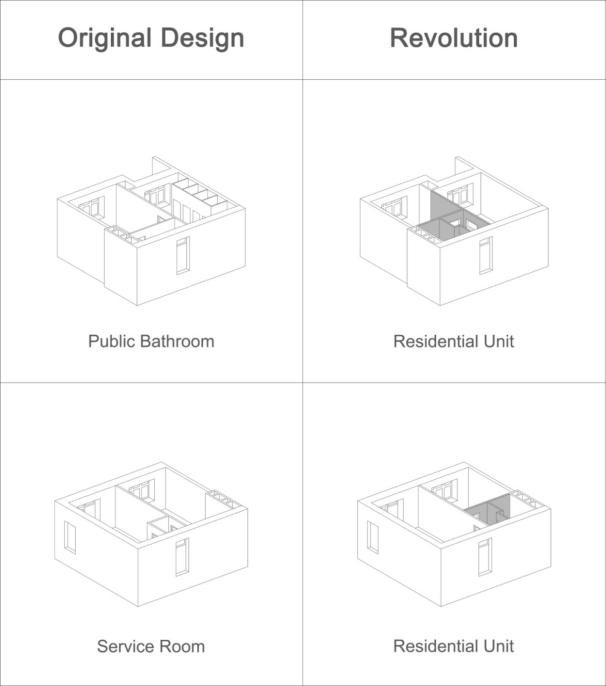

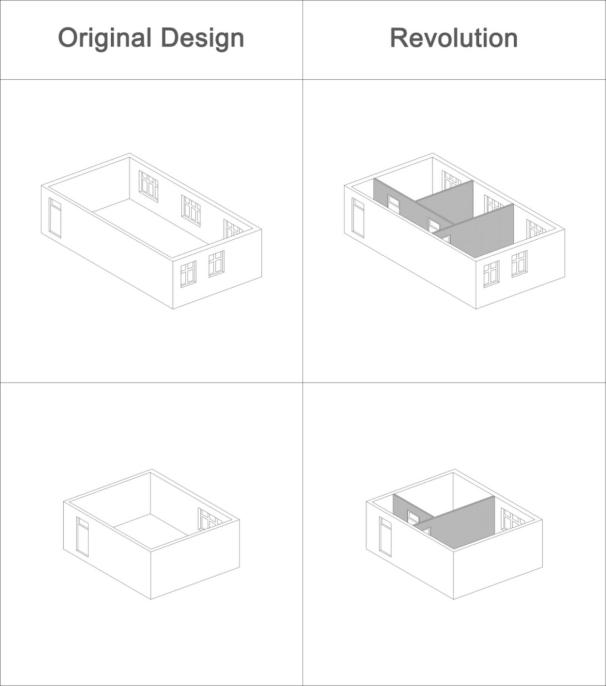

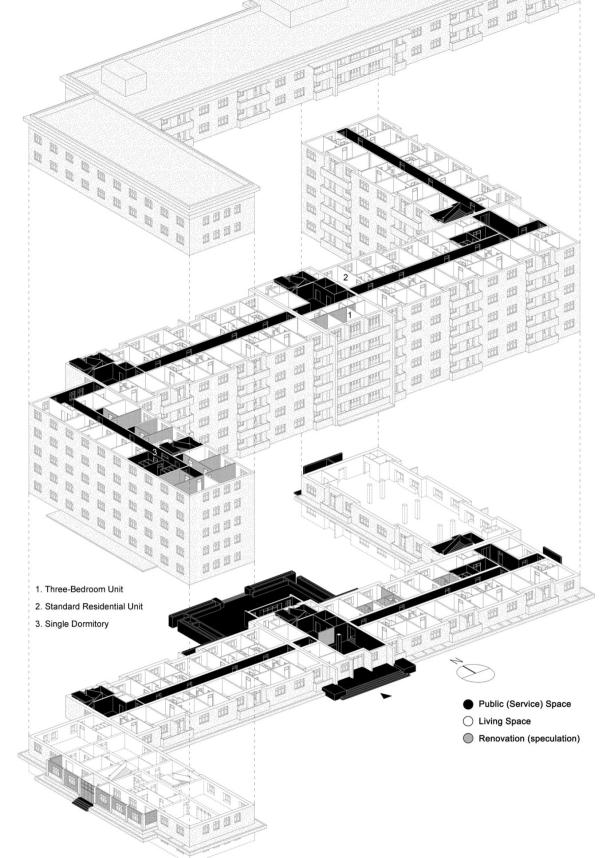

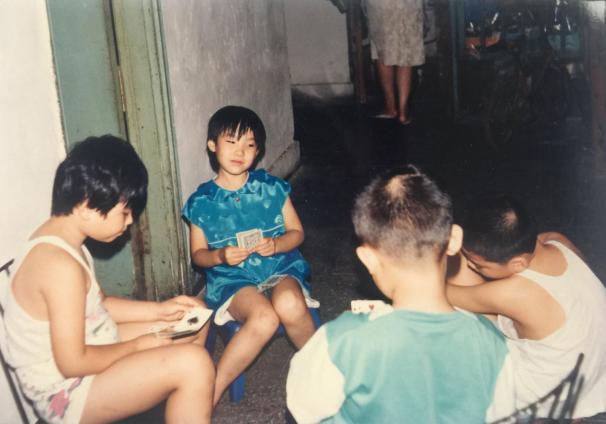

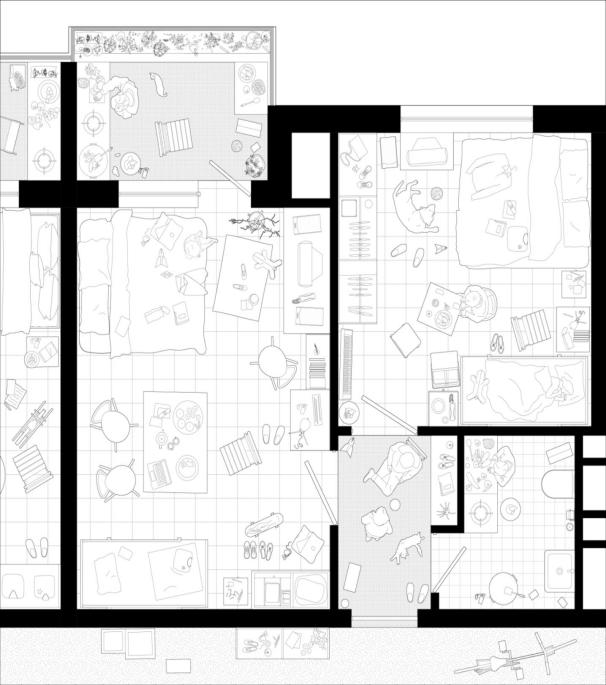

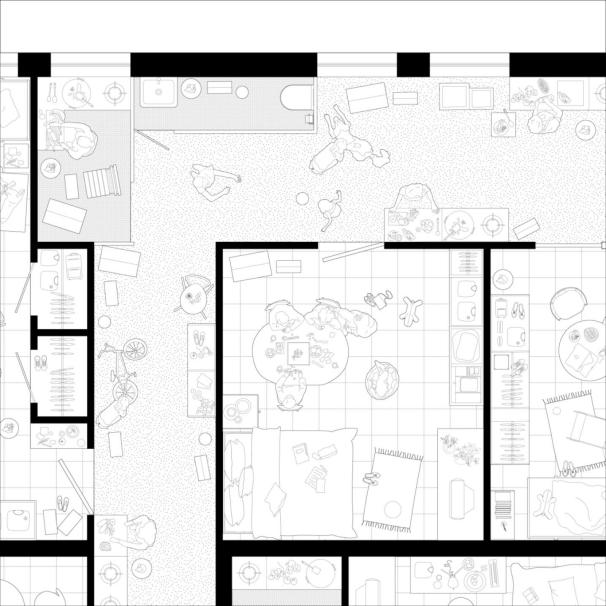

More than a year after the building's completion, China entered a three-year period of economic crisis, and residents gradually became unable to afford the high costs of the public canteen, which was ultimately forced to close by the end of 1961. This closure of the canteen significantly impacted residents' daily lives, as the original design of the building did not include kitchens in each household. Cooking thus became a significant challenge that residents had to solve on a daily basis. By late 1961, households began using coal stoves in the corridors to cook, converting the hallways into makeshift kitchens (Fig 15). Due to the increasing demand for housing, ordinary workers and citizen families were allocated living spaces in the Fusuijing Building through their served workplace. After 1962, many of the building's original public spaces were gradually converted into living spaces (Fig 16) by the Housing Management Bureau [22]. The residential units in Sections I and II, initially designed for a single family with a living room and bedroom, were restructured to accommodate two families sharing one unit and a bathroom (Fig 17). In Section III, the larger standard-floor dormitory rooms were subdivided into smaller units (Fig 18), with families moving into what were originally single dormitory rooms (Fig 19-20). Only the long corridors, a general store on the first floor, and the public baths and toilets on the standard floors of Section III were remained as public spaces. During this period, the corridor became the largest public space in the building (Fig 21), serving not only as a kitchen, but also as a vital social hub where residents gathered, and the best place for children to play hide and seek (Fig 22-23). It can be said that the corridor reconnected the people in the building and turned out to be the most public and multifunctional space which remains the most of the socialist nature. From an architectural perspective, the original design vision had largely disappeared. However, for those who upheld collectivist ideals, their vision did not vanish; rather, it continued through the spontaneous spatial modifications made by the residents which grounded the vision and concept to real life.

|

|

Figure 15. Author. Corridor as Kitchen, 2024. Speculative Architectural Drawing. | Figure 16. Author. Renovating Public Spaces into Living Spaces, 2024. Speculative Architectural Drawing. |

|

|

Figure 17. Author. Standard Residential Unit for Two Families, 2024. Speculative Architectural Drawing. | Figure 18. Author. Analysis of Room Renovation on Standard Floors of the Section III, 2024. Speculative Architectural Drawing. |

|

|

Figure 19. Author. Speculated Floor Plans of Standard Section III of the Fusuijing Building in Collective Memory from 1962-1978, 2024. Speculative Architectural Drawing. | Figure 20. Yu Shuo. Group Photo with Friends at Home, 1994. Photograph. Obtained from original resident Yehang Yu |

|

|

Figure 22. Yu Shuo. Playing Cards in the Corridor, 1992. Photograph. Obtained from original resident Yehang Yu | |

Figure 21. Author. Fusuijing Building in Collective Memory from 1962 to 1978, 2024. Speculative Architectural Drawing. |

|

Figure 23. Author. Playing in the Corridor, 2024. Speculative Architectural Drawing. |

In 1973, after years of abandonment, the former public canteen was converted into a youth center. The kindergarten in the building also closed after the Cultural Revolution period (1966-1976), and its first three floors were replaced by a sweater factory, while the basement was converted into a hotel. However, these transformed spaces did not serve the residents and quickly disappeared from the memory (Fig 24).

Figure 24. Author. Renovating an Abandoned Public Canteen into a Youth Center, 2024. Speculative Architectural Drawing.

Following the Reform and Opening-Up in 1978, the widespread adoption of gas stoves triggered a second wave of spontaneous renovations. Residents enclosed their balconies to create kitchens and converted the public toilets into kitchens for two families. As a result, the usage of the public toilets and kitchen increased significantly, the entrance halls became waiting areas as well as the most dynamic public space for the two families, connecting them into a small collective unit (Fig 25-26). As the entrance halls and toilets replaced the functions of corridors, kitchens, and some public spaces, residents in Sections I and II gradually repurposed the corridors for storage (Fig 27-28), and did not bother to repair the corridor lighting. Thus, in their collective memory, the corridors became chaotic, dim spaces that were disliked, except for children who found them ideal for playing hide-and-seek (Fig 29). The modifications to the balconies changed the architectural facade of the Fusuijing Building overwhelmingly (Fig 30), showcasing different families' living conditions.

|

|

Figure 25. Author. Enclosing the Balcony to Convert it into a Kitchen, 2024. Speculative Architectural Drawing. | Figure 26. Author. Living Together, 2024. Speculative Architectural Drawing. |

|

|

Figure 27. Unknown. Home Entrance Cluttered with Items, 2016. Photograph. Obtained from Yi Fu | Figure 28. Li, Wei. Various items piled up in the corner of the side building of the Fusuijing Building, 2019 Photograph. |

|

|

Figure 29. Author. Child Playing Among the Clutter, 2024. Speculative Architectural Drawing. | Figure 30. Author. Facade of the Fusuijing Building in Collective Memory from 1978-2005, 2024. Speculative Architectural Drawing. |

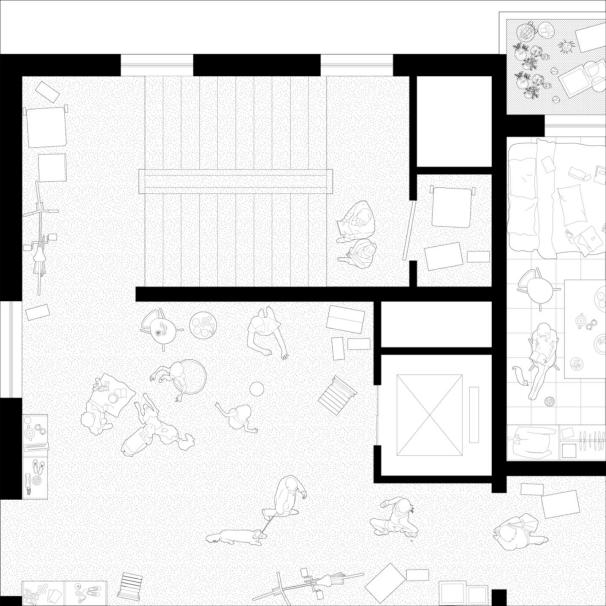

At the same time, an alternative way of life persisted in Section III. Since its standard floors were originally designed as single dormitories without balconies, residents began to occupy parts of the corridors as their own cooking areas (Fig 31-33), continuing lifestyle of sharing toilets and bathrooms after 1962, with corridors connecting each family into a small community.

|

|

Figure 31. Author. Speculated Floor Plans of Standard Section III of the Fusuijing Building in Collective Memory from 1978-2005, 2024. Speculative Architectural Drawing. | Figure 32. Author. Cooking in the Corridor (Section III), 1978-2005, 2024. Speculative Architectural Drawing. |

Figure 33. Unknown. Occupying the Corridor as a Kitchen, 2016. Photograph. Obtained from Yi Fu

Undoubtedly, the grand social vision from top to bottom of the building's initial design disappeared within just over a year of its completion. However, the residents practiced a feasible commune life through bottom-up transformations. Ironically, the kitchen, which was excluded in the initial design, became the carrier of this social vision. Whether repurposed corridors or public toilets functioned as kitchens, they both symbolized small yet persistent flames sustaining the ideal of "living together." This continued and sustained the collective memory of sharing in the Fusuijing Building [23] (Fig 34).

Figure 34. Author. Floor Plan of the Fusuijing Building in Residents' Collective Memory, 2024. Speculative Architectural Drawing.

References

[1]. After the signing of the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance in 1950, a wave of comprehensive learning from the Soviet Union surged across China.

[2]. Gosseye, J., Stead, N., & Van, D. (2019). Speaking of Buildings: Oral History in Architectural Research. Princeton Architectural Press.

[3]. Located in Marseille, France, designed by the architect Le Corbusier.

[4]. The original text of the "Resolution on Several Issues of People's Communes": "In the future, the people's communes in cities will also take a form suitable for urban characteristics, becoming tools for transforming old cities and building new socialist cities, becoming unified organizers of production, exchange, distribution, and people's livelihood welfare, and becoming social organizations that integrate government and society with the combination of workers, peasants, merchants, students, and soldiers."

[5]. Shi, T. (2002). I and the Temple of Earth. Spring Wind Literature and Arts Publishing House.

[6]. Lin, Y. (2011). Communist Building - China Youth Daily. China Youth Daily. https://zqb.cyol.com/html/2011-08/31/nw.D110000zgqnb_20110831_1-12.htm

[7]. The socialization of household: The process by which various household chores necessary for fulfilling the personal subsistence of family members and maintaining various family functions are gradually transformed into socialized services provided by social organizations. The basic content includes: the commodification of household consumer goods and the socialization of domestic services.

[8]. From 1958 to 1960, Beijing planned to build four People's Commune buildings at Fusuijing (now No. 1 Gongmenkou San Tiao, Baita Temple, Xicheng District), Beiguan Hall (now No. 14 Beiguan Hall Hutong, Dongcheng District), Anhua Temple (now No. 14 Guangqumen Inner Street, Dongcheng District), and Baizhifang, of which the Baizhifang building was not completed for unknown reasons, and the other three were the first eight to nine-story residential buildings with elevators in Beijing.

[9]. Mao, Y. (2018). A Half-Century of Prosperity and Decline of Anhualou - China News Weekly. China News Weekly. http://www.zgxwzk.chinanews.com.cn/2/2018-06-13/1144.shtml

[10]. Jian, S. (2016). The 'Marseille Apartment' in Beijing | China space research plan 07 (Appendix). Archiposition. https://www.archiposition.com/items/20180525102414The design of the Fusuijing Building is an upgraded version of the original plan, the Anhua Building is the closest to the original plan, and the Beiguan Hall Building is a simplified version.

[11]. In the thought of Marxist historical materialism, it is emphasized that the masses are the creators of history.

[12]. Willimott, A. (2017). ‘How Do You Live?’: Experiments in Revolutionary Living after 1917. The Journal of Architecture, 22(3), 437–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2017.1307870

[13]. Li, R., Wu, C., & Yang, Y. (2018). Conservation and Reuse of Modern Architecture Heritage: Taking Fusuijing Building as an Example. Research on Heritages and Preservation, 3(10), 89.

[14]. Halbwachs, M. (1975). The Social Framework of Memory. Ayer Co Pub.

[15]. Halbwachs, M. (1992). On Collective Memory. University of Chicago Press.

[16]. Rossi, A. (2002). The Architecture of the City. MIT Press.

[17]. Due to the serious "left" errors in the Great Leap Forward and the People's Commune movement, coupled with the large-scale natural disasters that Chinese farmland suffered for several consecutive years from 1959 to 1961, New China faced the most severe economic difficulties since its founding.

[18]. The Cultural Revolution was an internal chaos mistakenly initiated by leaders, exploited by counter-revolutionary groups, and brought severe disaster to the Party, the state, and people of all ethnicities.

[19]. Reform and Opening Up refers to the exploration and innovation conducted by the Communist Party of China in leading the Chinese people on the path of socialist construction since 1978. It is a new great revolution. Its goal is to liberate and develop productive forces, enrich the Chinese people, modernize China, achieve the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, and find a path of socialism with Chinese characteristics that suits the national conditions.

[20]. After the founding of the People's Republic of China, a unique form of housing allocation emerged during the era of the planned economy. Urban residents' housing needs were primarily addressed by their work units. Various levels of government and work units constructed housing according to the national basic construction investment plan. Once the housing was completed, it was allocated to employees based on a series of conditions such as rank, years of service, age, number of residents, generations, number of people, and whether they already had housing. Only a nominal rent was charged.

[21]. The Housing Management Bureau is a department of the People's Government responsible for the management, repair, and renovation of public housing, as well as the collection of rent.

[22]. The influence of this "social vision" is not only on the use of architectural space. A former resident of the Fusuijing Building who has immigrated to Australia said in a chat with the author, "Even though I have lived abroad for many years, the daily living style of the Fusuijing Building during my childhood still influences me, such as thinking collectively first, then individually."

Cite this article

Mo,N. (2025). Another Fusuijing Building: collective memory, reconstruction, and the echoes of the past. Advances in Humanities Research,12(1),49-61.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Humanities Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. After the signing of the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance in 1950, a wave of comprehensive learning from the Soviet Union surged across China.

[2]. Gosseye, J., Stead, N., & Van, D. (2019). Speaking of Buildings: Oral History in Architectural Research. Princeton Architectural Press.

[3]. Located in Marseille, France, designed by the architect Le Corbusier.

[4]. The original text of the "Resolution on Several Issues of People's Communes": "In the future, the people's communes in cities will also take a form suitable for urban characteristics, becoming tools for transforming old cities and building new socialist cities, becoming unified organizers of production, exchange, distribution, and people's livelihood welfare, and becoming social organizations that integrate government and society with the combination of workers, peasants, merchants, students, and soldiers."

[5]. Shi, T. (2002). I and the Temple of Earth. Spring Wind Literature and Arts Publishing House.

[6]. Lin, Y. (2011). Communist Building - China Youth Daily. China Youth Daily. https://zqb.cyol.com/html/2011-08/31/nw.D110000zgqnb_20110831_1-12.htm

[7]. The socialization of household: The process by which various household chores necessary for fulfilling the personal subsistence of family members and maintaining various family functions are gradually transformed into socialized services provided by social organizations. The basic content includes: the commodification of household consumer goods and the socialization of domestic services.

[8]. From 1958 to 1960, Beijing planned to build four People's Commune buildings at Fusuijing (now No. 1 Gongmenkou San Tiao, Baita Temple, Xicheng District), Beiguan Hall (now No. 14 Beiguan Hall Hutong, Dongcheng District), Anhua Temple (now No. 14 Guangqumen Inner Street, Dongcheng District), and Baizhifang, of which the Baizhifang building was not completed for unknown reasons, and the other three were the first eight to nine-story residential buildings with elevators in Beijing.

[9]. Mao, Y. (2018). A Half-Century of Prosperity and Decline of Anhualou - China News Weekly. China News Weekly. http://www.zgxwzk.chinanews.com.cn/2/2018-06-13/1144.shtml

[10]. Jian, S. (2016). The 'Marseille Apartment' in Beijing | China space research plan 07 (Appendix). Archiposition. https://www.archiposition.com/items/20180525102414The design of the Fusuijing Building is an upgraded version of the original plan, the Anhua Building is the closest to the original plan, and the Beiguan Hall Building is a simplified version.

[11]. In the thought of Marxist historical materialism, it is emphasized that the masses are the creators of history.

[12]. Willimott, A. (2017). ‘How Do You Live?’: Experiments in Revolutionary Living after 1917. The Journal of Architecture, 22(3), 437–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2017.1307870

[13]. Li, R., Wu, C., & Yang, Y. (2018). Conservation and Reuse of Modern Architecture Heritage: Taking Fusuijing Building as an Example. Research on Heritages and Preservation, 3(10), 89.

[14]. Halbwachs, M. (1975). The Social Framework of Memory. Ayer Co Pub.

[15]. Halbwachs, M. (1992). On Collective Memory. University of Chicago Press.

[16]. Rossi, A. (2002). The Architecture of the City. MIT Press.

[17]. Due to the serious "left" errors in the Great Leap Forward and the People's Commune movement, coupled with the large-scale natural disasters that Chinese farmland suffered for several consecutive years from 1959 to 1961, New China faced the most severe economic difficulties since its founding.

[18]. The Cultural Revolution was an internal chaos mistakenly initiated by leaders, exploited by counter-revolutionary groups, and brought severe disaster to the Party, the state, and people of all ethnicities.

[19]. Reform and Opening Up refers to the exploration and innovation conducted by the Communist Party of China in leading the Chinese people on the path of socialist construction since 1978. It is a new great revolution. Its goal is to liberate and develop productive forces, enrich the Chinese people, modernize China, achieve the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, and find a path of socialism with Chinese characteristics that suits the national conditions.

[20]. After the founding of the People's Republic of China, a unique form of housing allocation emerged during the era of the planned economy. Urban residents' housing needs were primarily addressed by their work units. Various levels of government and work units constructed housing according to the national basic construction investment plan. Once the housing was completed, it was allocated to employees based on a series of conditions such as rank, years of service, age, number of residents, generations, number of people, and whether they already had housing. Only a nominal rent was charged.

[21]. The Housing Management Bureau is a department of the People's Government responsible for the management, repair, and renovation of public housing, as well as the collection of rent.

[22]. The influence of this "social vision" is not only on the use of architectural space. A former resident of the Fusuijing Building who has immigrated to Australia said in a chat with the author, "Even though I have lived abroad for many years, the daily living style of the Fusuijing Building during my childhood still influences me, such as thinking collectively first, then individually."