1. Introduction

The theory of physicality provides a dual-dimensional perspective for interpreting pictorial stones: the body is not only an object of image representation, but also a subject involved in the construction and perception of cultural meanings. The structural connections embodied in the body have also formed another space at the level of symbolic forms [1]. Through the depiction of physicality postures, the symbolic translation of real-world behaviours can be achieved.

In China's localised sacred spaces, sacredness does not exist in isolation either inside or outside the space; instead, it resides in the Tian-ren connection and can be understood through a series of concepts, representations, experiences, ritual norms, and social orders [2].

In the funerary culture of the Eastern Han Dynasty, the ways of handling the body fundamentally constitute a concrete construction of physicality continuity, which is achieved through the ritualization of physicality postures, the interaction between the body and space, and the coordination of physicality symbols. The embodiment of the physicality in pictorial narratives centres on the interaction between physicality gestures, movements and symbolic systems.

The spatial layout of pictorial stones in Eastern Han dynasty tomb chambers contains sophisticated logic. In the northern Shaanxi region, pictorial contents are concentrated in the tomb gate called "Tian-men", while in the Sichuan region, "Tian-men" are extensively presented in the form of "Que-men"—tower like gate structures—images on the sarcophagi inside the tombs. Moreover, due to the particularity of the content related to "Tian-men", the tomb gate or stone coffin where "Tian-men" is located becomes a visual focal point, and is constructed as the "Tian-men" symbolizing the entrance to the heaven [3].

The horizontal symmetrical composition not only stems from the mechanical needs of the architectural structure but also corresponds to the Eastern Han dynasty philosophical concept of "Yin-yang duality"; the distribution of images in upper and lower layers reflects the Han dynasty cosmology—themes of the heaven often occupy the highest position in the images, and through the vertical spatial sequence, they symbolize the tomb owner entering the immortal world governed by the Queen Mother of the West [4]. When ritual participants step into the tomb chamber, their processional routes, visual focus points and worship actions form a dynamic interaction with the pictorial symbols, transforming the static stone materials into a medium for feeling sacredness [5].

This paper focuses on funerary ritual-related pictorial stones and other tomb components within burial materials of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 CE). It aims to construct an interpretive framework of "image narrative—physicality perception—sacredness generation" by analysing physicality expressions, symbolic meanings, spatial orientations in pictorial stones, as well as the simulation of worshippers' bodies in ritual contexts, thereby introducing a new perspective to the study of the Eastern Han Dynasty pictorial stones. Through the analysis of image narratives and spatial layouts, this paper examines the sacredness of tombs from the dimensions of physicality perception and ritual practices.

2. Theoretical foundations of sacredness and physicality

2.1. Physicality and sacredness

Physicality refers to the body as the core carrier of cultural meanings, presenting a spatial mode of existence [6]. Within tombs, the body participates in ritual construction, expression of beliefs, and spatial interaction through physical characteristics such as postures, movements and transformations. Material carriers may also acquire sacredness by alluding to the body.

This paper, from the perspective of physicality, transcends the traditional "mind-matter" dualism and reduces abstract concepts to concrete physicality practices, such as rituals and beliefs. Book of Rites · Jiao Te Sheng presents a similar view: "Hun qi (the vital essence of the soul) returns to heaven; Xing po (the corporeal essence of the form) returns to earth [7]".

In the construction of tomb chambers, craftsmen associated physicality postures with ritual norms, concepts and cosmic views of life through stylised compositional patterns and the appropriation of mythological and historical symbols (Figure 1).

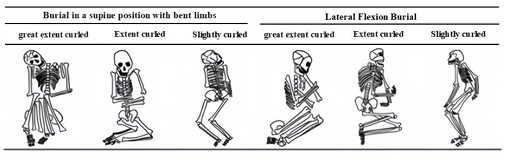

In the Eastern Han dynasty funerary rituals, the perception of the body among the Han people, transcended the material realm, developing the concept of "the body as a sign". The "flexed burial" (Figure 2) and "kneeling figurines" (Figure 3) [8] in tombs are another form of expression of physicality.

Kneeling figurines of the Eastern Han Dynasty, through their stylised knee-bending and body-bowing movements, transform "worship" in real-world rituals into the perpetual order within tombs. The body becomes a symbol that sustains beliefs regarding life and death [9], and its original function and symbolism should be examined within the context of rituals [1].

Sacredness is not an absolute separation; rather, it constitutes the vital integration of "heaven—human—deity", through the isomorphism of physicality postures, spatial layouts and cosmic order, and is characterised by "fluidity, pan-ness and integration" [12].

With the image and spatial narratives of the tomb chamber as material carriers, a dynamic integration between "from the mundane world to the transcendental realm" is formed. Through the stylised transformation of images, they are converted into symbols of the authority of the heaven [5], and sacredness is perceived through physicality experience.

Meanwhile, the sacredness, through the spatial construction of verticality (columns) and depth (courtyards) [12], integrates individual life into the cosmic order of the universe, rendering the tomb a field of meaning where "heaven, earth, humans and deities" coexist. In major clan sacrifices or other religious prayers and rituals, kneeling physicality rituals can also be frequently observed. The inward-outward process forges the connection between sacredness and rituals, making the guidance of tomb structures on physicality perception constitute the foundation of sacred experience.

2.2. Living's physicality and sacredness

The physical practices of the living within the funerary field constitute a dimension in the construction of the sacredness of tombs. The Eastern Han people believed: "The living have their own dwellings, and the deceased have their own coffins. The realms of the living and the dead are separate, and there should be no interaction between them" [13].

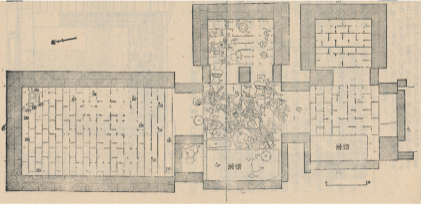

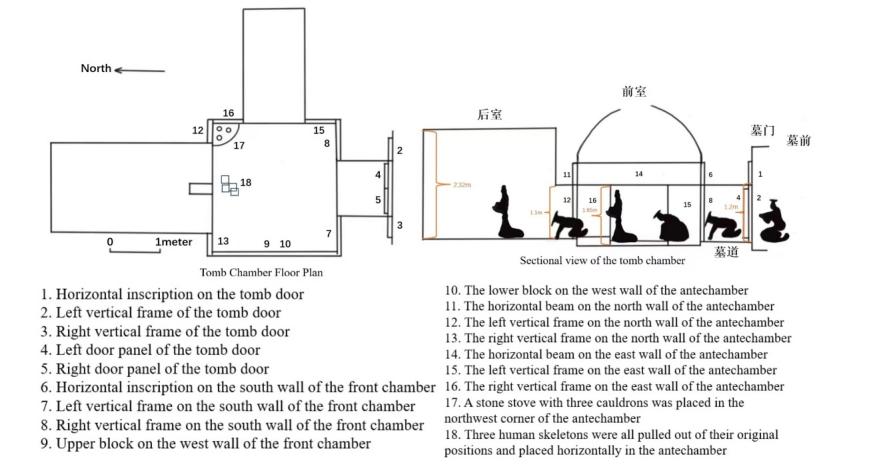

This awareness of spatial segmentation prompts the living to intensify their sacred experience through physicality rituals. The concentrated occurrence of pictorial content at the tomb gates in Eastern Han tombs [3], coupled with the tomb chamber's progressive structure of "anterior chamber—posterior chamber—side chamber" (Figure 4), constructs the trajectory of physicality movement for the living when entering.

As the living proceed through the tomb passage, their physicality behaviours transition from a kneeling posture to crawling with the body bent forward, and finally to standing upright. Their line of sight, obstructed by the tomb door panels, forms a visual barrier [3]. The tomb passage, thus, generates spatial oppression and visual guidance, eliciting a sense of awe.

The physical experience intertextually resonates with the regulation in Guan zi · Ba Guan: "The construction of palaces and chambers must also have limits, and the felling and closure of mountains and forests must also have fixed times" [14], demonstrating that the sanctity of burial sites stems not only from symbolic imagery but also fundamentally relies on the physical perception of spatial dimensions.

The sacrificial ritual constitutes the core of the interaction between the living and the sanctity of the burial site. The Eastern Han Dynasty held the belief that "The tombs are the abode of spirits and the site of sacrificial rites" [16].

The kneeling and prostration rituals in the ancestral hall make the physicality postures of the living transition from standing upright to prostration, thereby accomplishing the expression of reverence towards ancestral spirits [9]. At this point, the normativity of physicality movements constitutes the affirmation of sacredness.

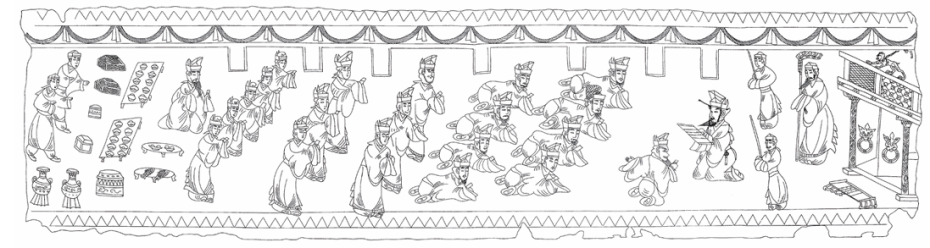

The specific positioning of the "Tian-men" pictorial images further intensifies the ritualistic responses of the body. Visual symbols awaken the physicality memories of the living, and visual practice is transformed into embodiment experiences [5]. In the pictorial images of the Wushi Shrine in Jiaxiang, Shandong, the collective posture of worshippers leaning forward with hands holding tablets is solidified into collective memory through visual symbols, enabling the bodies of the living to form a conditioned reflex-like sacred perception in repeated rituals [4].

2.3. Deceased's sacredness and physicality

The mortuary practices of the Eastern Han Dynasty consistently revolved around the dual beliefs of "the divergence of life and death" and "the immortality of the soul". The tomb structure itself constitutes a sacralising construction of the deceased's remains.

The handling of the sacredness of the deceased's remains by people of the Eastern Han Dynasty is generally reflected in the following two aspects: on the one hand, the principle of "resembling life" is employed to maintain the physical form of the remains, such as the form of coffins and outer coffins, and burial objects; on the other hand, the transformation of the soul is achieved through the symbolization of physicality postures.

Eastern Han people regarded tombs as places to house the deceased, which was also related to their fear that the souls of the deceased might follow the living [9]. Meanwhile, they held that tombs should conform to the principle stated in "Funeral rituals involve adorning the deceased in the manner of the living; they imitate the conditions of life to send off the dead" [17]. Stone stoves and model pottery granaries were placed in the anterior chamber, while coffin platforms were set in the posterior chamber; burial objects were arranged according to the logic of "food and dwelling". This not only met the material needs of the deceased's "body", but also implied the transition of their souls to the immortal realm, through spatial hierarchy.

Placement is better manifested as the protection of the body. The Jie Chu texts (texts of dispelling misfortune) of the Eastern Han people more explicitly articulate the concept that tombs are places to house the deceased [9]. It can be observed that the Eastern Han people isolated the spaces of life and death through written incantations.

Meanwhile, the seal of the coffin and the solidity of the tomb chamber serve to strengthen the protection of the body at the physical level. Moreover, the continuation of the flexed burial style was transformed into ritual constraints on the deceased's remains during the Han Dynasty; through the stylization of the physicality postures in supine extended burials, the deceased's remains became a medium connecting life and death.

The connection between the deceased's physicality and sacredness are embodied in the physicality practices of funerary rituals. Lun Heng · Bo Zang Pian records: "Regard the dead as one would the living; pity the dead being buried alone, their souls left lonely and unaccompanied" [18], which reflects the Eastern Han people's dual perception of the deceased's remains: it is necessary both to maintain the secular order through the posture of "resembling life" and to achieve soul control through physicality handling.

The "Tian-men" inscriptions and images of twin towers on the front panel of the stone coffin in the Han tomb at Guitou Mountain, Jianyang, Sichuan [3] transform the tomb owner's body into a sacred narrative through ritual processes, where the body becomes the key to bridging the boundary between life and death.

3. Ritual practices and spatial construction

3.1. Physicality engagement in funerary ritual

"Mourning" and "sacrifice" are two distinct ritual processes, each encompassing different contents. As stated in Book of Rites, "In mourning, observe one's grief" and "In sacrifice, observe one's reverence" [19], the phenomenon of setting up offerings inside tombs during the Han Dynasty constituted an emerging funerary ritual—a one-time sacrificial ceremony. Its implementation could only be accomplished in brick-chambered or cave-chambered tombs with a certain amount of space [20].

The deceased's remains would commence their journey from the "Zhong Liu" (central eave), progressing sequentially through "Hu Xia" (below the window), "Hu Nei" (inside the doorway), "Zuo" (the eastern steps), "Ke Wei" (the guest position) and "Ting" (the courtyard), ultimately reaching the tomb chamber. This ritual process, proceeding from the inside out, enables the longitudinal extension of space and the dredging of individual emotional experiences to emerge synchronously and advance layer by layer (Figure 5) [2].

In Han Dynasty, the tomb passage and antechamber, as arenas for interaction between the living and the tomb chamber space, see their spatial design and spatial narrative jointly construct physicality practices. The living's viewing behaviour and physical participation are not passive receptions but active embodiments of the concept "Serve the living as one serves the dead" [21], achieved through spatial movement and ritual engagement.

The tomb gate constitutes a key node in the rituals of life and death. As a physical passage connecting the tomb gate to the antechamber, the tomb passage derives its sacredness first and foremost through its architectural form. Mao Shi Zheng Yi, records that "A tomb has a gate, hence the term 'tomb gate' which refers to the gate of the tomb passage" [23].

Furthermore, the exorcism text unearthed at Dou jitai from the fourth year of the Yongyuan era (92 CE) contains the phrase: "The living enters the residence; the dead enter the coffin" [24]. This statement emphasizes that life and death each have their own designated realms.

Taking the M1 tomb at Guanzhuang as an example (Figure 6), the tomb gate stands at a height of 1.2 meters, while the antechamber, starting from 1.65 meters above ground level, features walls that arch inward to form a four-sided pyramidal roof, the height of which remains unspecified [25]. As can be inferred from the sectional view in Figure 6, the height of the tomb passage is also approximately 1.2 to 1.3 meters. It can thus be deduced that when entering the tomb chamber, the living had to adopt a posture of "bending forward to move" or "proceeding slowly" to pass from outside the tomb through the tomb passage into the antechamber. This physical movement of the body constrained by the spatial form was transformed into a ritualistic action—gradually entering the underground dark space from the bright world above ground, which metaphorizes the Han people's funerary concept that "the paths of life and death are distinct" [26].

The construction of a sacred space can only realize its significance by relying on the physical presence of the body. As a symbolic structure marking the boundary between life and death, the sacredness of the tomb gate is activated through the "passage ritual" of the living body. Without human perception, the tomb passage is merely a physical corridor, incapable of functioning as a spiritual vessel that embodies concepts of life and death.

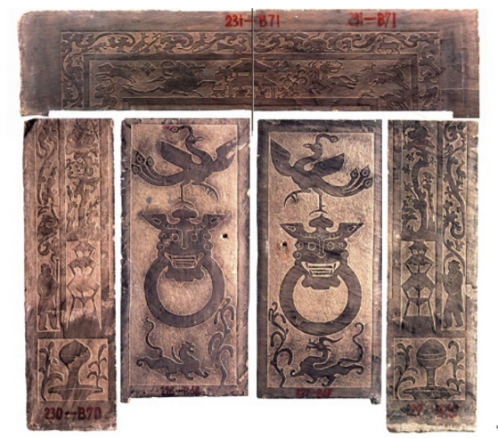

Taking the M1 tomb gate at Guanzhuang as an example (Figure 7) [25], the lintel decoration is divided into inner and outer registers. The outer register features a cloud-scroll pattern, with two long-necked birds standing face to face on top of the inner-register pavilion. The inner register depicts a scene of chariots and riders with a pavilion. The hall depicted in the centre features hanging curtains [10], the door leaves are adorned with huge images of animal-shaped door knockers holding rings in their mouths.

When the tomb door leaves swing inward, the living bend down to enter the chamber and proceed to the front of the southern wall (Figure 8). The line of sight, directed from bottom to top, is first drawn to the images of peacocks, covered carriages, and scenes of feeding horses under tree shade on the left and right vertical frames. Gradually moving upward, it reaches the Ruyi patterns on the horizontal lintel of the southern wall, interspersed with immortal birds, divine beasts, and a procession scene consisting of ten horses, five carriages and eighteen people [25].

The entire entry process constitutes a spatial transition "from the secular to the sacred". The tomb passage possesses the power to connect, reconcile and integrate, linking the originally fragmented spaces endowed with sacredness.

Large stone-chambered tombs with pictorial carvings in the Han Dynasty generally had two halls: one was the middle chamber or antechamber in the underground tomb, which was adjacent to the rear chamber and located in front of it; the other was the ancestral hall at the tomb site [27]. As an open space within the tomb, the antechamber carries the sacred functions of the living's sacrificial rituals, social interactions and expressions of faith, and its spatial significance is continuously reconstructed through physicality participation.

The antechamber also provides a venue for the extension of burial rituals. Therefore, the antechamber is not a static concept; it is a spiritual cosmos of sacred space. Through physicality actions such as placing sacrificial offerings and kneeling in prayer, the living construct a sacred connection of "serving the dead as one serves the living", endowing artifacts with the sacred function of communicating between life and death.

Taking the Beizhai Han Tomb as an example, the antechamber first served as a ritual space with the function of offering sacrifices. This significant cultural attribute determines it to be the largest and tallest section of the tomb, as described in Shiming · Shi Gongshi: "A hall (tang) is like a grand hall, with a lofty and prominent appearance" [28]. Secondly, it also symbolised the main hall of the mansion in the netherworld, serving as a place where the tomb owner received guests and held feasts [1].

When burial objects enter the antechamber, their nature undergoes transformations: there is a shift from "mingqi" to sacrificial utensils, as well as a transition from objects for the living to burial artifacts. Meanwhile, the antechamber endows these objects with the sacred function of communicating between life and death. Their transformation in nature within the antechamber, relying on the physicality practices of the living, achieves an elevation from the secular to the sacred. When the tomb gate is closed, the nature of all objects is fully realised, becoming "mingqi" owned and used by the tomb occupant in this enclosed eternal world [20].

People in the Eastern Han Dynasty believed that tombs should "bring lasting benefits to descendants". As the tomb owner's possessions in the sacred world, burial objects not only satisfy their needs for an "eternal life" but also symbolize the continuation of the family's well-being through "the immortality of artifacts".

Meanwhile, the scene of setting up offerings in the tomb transforms from the living's sacrifice to the deceased into the tomb owner's eternal feast. Therefore, as the most important part of the entire tomb and its chambers, the antechamber serves as a crucial arena for spiritual communication between the living and the dead.

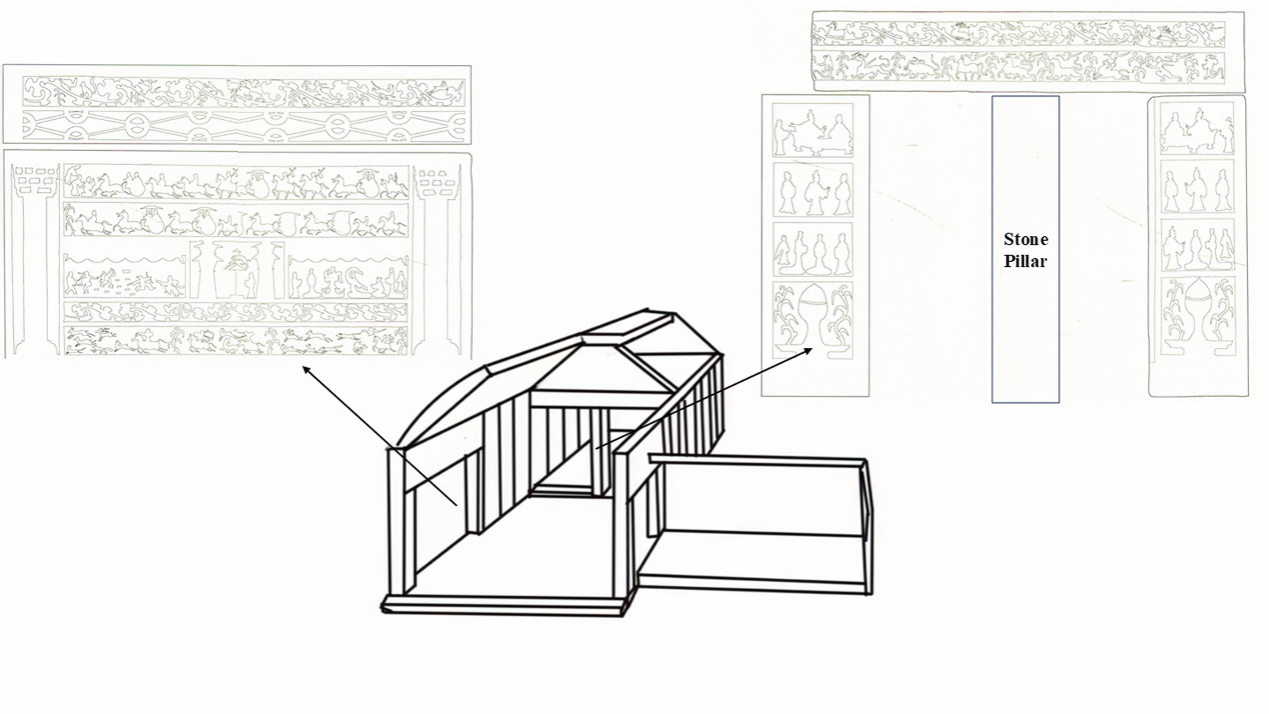

3.2. The physicality and sacredness of the deceased

Tombs of the Eastern Han Dynasty mostly adopted a residential-like simulation with a "front hall and rear chamber" structure [20]. The rear chamber, usually located at the innermost part of the tomb, highlights the deceased's remains as the core of the tomb through spatial progression. Its floor is higher than that of the front hall, with the coffin placed in the centre; the four walls are carved with images of the Queen Mother of the West and feathered immortals (Figure 9). Through such spatial progression and the superposition of symbols, the deceased's remains becomes the ultimate destination of this "residential simulation".

Taking the Guanzhuang M1 Han Tomb as an example, the floor of the rear chamber is 0.1 meters higher than that of the front chamber, with a stone pillar 0.2 meters in width standing in the middle, dividing it into two parallel passageways [25] (Figure 10). This arrangement thus enhances the privacy of the space where the deceased's remains resides.

The construction of the sacredness of the tomb chamber space is by no means merely emphasizing the space itself; rather, it is the deities in the pictorial stones that endow this place and the stone coffin with a sacred aura. Therefore, the stone coffin, as the carrier for placing the deceased's remains, directly participates in the deceased's experience of sacredness. Among all the discovered pictorial stone coffins, most of the images depict the immortal realm and ascension to immortality [29]. The purpose is to enable the deceased to reach the immortal world where one can achieve eternal life, which is the most fundamental reason for the appearance of images of the Queen Mother of the West on stone coffins [30].

Thus, the deceased's remains is not only a physical continuation of earthly life but also a sanctified and immortal vessel within the auspicious belief system. The ascension to heaven discussed in the Han Dynasty's immortality ideology was, to a greater extent, a pursuit of eternal life without death [31].

Taking the stone coffin paintings in Sichuan as an example, not only do the "Que-men" images on some front panels imply a connection with Mount Kunlun, where the Queen Mother of the West resides, but the pictorial contents on the side panels and even the rear panels of the stone coffins also, in fact, mostly constitute specific depictions of that deathless world where the Queen Mother of the West dwells.

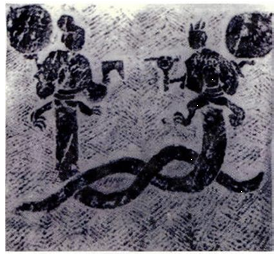

Taking the pictorial carvings on the Hejiang No.4 stone coffin as an example, although only a pair of gate towers are engraved on its front panel, on its left and right-side panels, one side depicts a carriage carrying the owner towards a building complex, beside which sits the Queen Mother of the West on Mount Kunlun (Figure 11). The other side is carved with immortal spirit beasts such as toads, black bears, nine-tailed foxes and three-legged crows (or the three blue birds of the Queen Mother of the West) (Figure 12). The rear panel is carved with Fuxi and Nuwa holding the sun and moon discs in their hands (Figure 13) [32].

Therefore, the emphasis on the "physicality" of the deceased in the Han Dynasty was, in essence, the ultimate embodiment of the concept of "serving the dead as one serves the living"—the continuation of the body in the underground world was the core of funeral practices, while sacredness provided support for the eternal existence of the body, through symbolic systems such as the Queen Mother of the West and auspicious omens.

The tomb gates of the Eastern Han Dynasty in northern Shaanxi transformed the tomb gate visually into a "Tian-men" through symbols such as the sun, moon, clouds, and ganoderma, symbolizing that the tomb owner's body enters the immortal realm through this gate. Similarly, the double "Que-men" images on the front panels of Sichuan stone coffins are self-inscribed as "Tian-men". Like the tomb gates, "Que-men" equate the gate-towers to the passage for ascension to immortality, reflecting people's concepts of life and death as well as their belief in ascension to immortality at that time.

The use of such a pictorial symbol as "Que" in the tomb "is regarded as a symbolic theological means that, acting as a 'ladder to heaven', guides people to ascend to heaven" [33]. The symbolic representation indicates that the tomb owner has successfully passed through the "Tian-men" and entered the immortal realm presided over by the Queen Mother of the West [3].

"Que-men" and the "Tian-men" refer specifically to the gates of the yin residence (the abode of the deceased) represented by the coffin, outer coffin, or tomb chamber. At the tomb gate of Cave 4 in Qigedong, Baomin Village, Changning, Sichuan, a "Que-men" is carved, with the inscription "Zhao Shi Tian-men" beside it [31].

The character "是" (Shi) is a substitute for "氏" (Shi, meaning "family"), a usage commonly seen in mirror inscriptions. Thus, this "Tian-men" is privately owned by the Zhao, providing irrefutable evidence for the nature of such que gates: they are the gates of private yin residences (abodes of the deceased), not thoroughfares leading to heaven. Though there are only four simple characters on the gate of Cave 4 in Qigedong, their meaning is expressed extremely clearly, leaving no room for misunderstanding [34].

The supine extended burial posture, central to Han funerary practices, utilizes pictorial representations on stone coffins to simulate universal order and "Que-men" motifs, facilitating the soul's celestial ascent. These elements serve as sacred intermediaries connecting the "mortal realm" with the "divine sphere", embodying the concept of "eternal posture" and imbuing the deceased with a sense of "sacredness".

Take the painting of Fuxi and Nuwa on the No. 1 stone coffin unearthed from the cliff tomb in Xinmin Village as an example. Under the two deities, there are two snakes copulating, with their heads pointing respectively to the lower bodies of Fuxi and Nuwa. The implication of copulation is unmistakable. All these express the deceased's desire to have their life continued and regenerated (Figure 14) [29].

It implies life regeneration through an intuitive physicality narrative, transforming reproductive acts into a symbol of cosmic order. The deceased's remains echoes the reproductive symbols on the coffin and outer coffin, interpreting death as a link in the cycle of life and endowing funeral rituals with a sacred meaning of regeneration.

Xunzi described the Warring States period's funerary concepts as "the grand emulation of life in seeing off the dead" [17]. This concept continued to be inherited into the Eastern Han Dynasty [9].

The pictorial carvings on coffins and outer coffins are not merely decorations; rather, through the interaction between the deceased's remains and the images, they enable the deceased to continue their social roles from life in the "post-mortem world", endowing death with the sacred meaning of "continuation of life".

4. Conclusion

This study, from the perspective of physicality, reveals that the core of the construction of sacredness in Eastern Han dynasty stone relief tombs lies in the interactive mechanism between the physical practices of the living, the symbolization of the deceased's remains and spatiality. The living, through physical behaviours such as processions and worship, establish ritualised connections with the narrative of the reliefs and the spatial layout, thereby activating sacred perceptions; the bodies of the deceased, by means of ritualised postures and symbols in the stone coffin reliefs, achieve the transformation from the secular to the sacred, while space, as a medium that carries the meaning of the body, permeates this entire process.

The physicality of both exhibits a progressive logic: the living transforms the secular space into a sacred field through physicality perception, while the deceased complete the narrative of ascension to immortality within the space by virtue of physicality symbols, and physicality serves as the core link in the generation and reinforcement of sacredness.

This study provides a focused analysis from the perspective of physicality for the interpretation of the sacredness of Eastern Han stone reliefs. In the future, the scope of regions and materials can be expanded to further explore the underlying logic of physicality symbols in the construction of sacredness in ancient funerary practices.

References

[1]. Zhang, J. (2019). A study on the pictorial narrative of Han dynasty stone reliefs [PhD dissertation]. Wuhan University. https: //doi.org/10.27379/d.cnki.gwhdu.2019.00223

[2]. Wang, Z.H. (2024). How is the de-boundaries sacredness possible? The construction mode of sacred space from the perspective of heaven-human relations. World Religious Cultures, (02), 160-166.

[3]. Li, Q.Q. (2015). Tomb gates and Tian-men: A study on the themes of stone reliefs on Eastern Han tomb gates in northern Shaanxi. Journal of the Arts, (02), 14-24.

[4]. Wu, H. (1989). The Wu Liang Shrine: The Ideology of Early Chinese Pictorial Art. Stanford University Press, 73-217.

[5]. Li, W.X. (2014). The shrine owner paying homage to the immortal messengers of the Queen Mother of the West: A query on the shrine owner being worshipped images in Han dynasty stone reliefs. Ancient Civilizations, 8(02), 68-77, 113-114. https: //doi.org/10.16758/j.cnki.1004-9371.2014.02.016

[6]. Guo, Y.Y. & Zhang, X.Y. (2021). The ethical movement of the transformation of views on death from physicality to embodied subjectivity. Medicine and Philosophy, 42(20), 33-37.

[7]. Ruan, Yuan. (Ed.). (2009). Jiao Te Sheng. In Shi San Jing Zhu Shu: Qing Jiaqing Ke Ben. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 3156.

[8]. Li, W.X. (2012). Physicality expression and pursuit of faith [PhD dissertation]. Shandong University.

[9]. Yang, A.G. (2020). Discovery and research on inscriptions on Han dynasty stone reliefs. Chinese Calligraphy, (12), 80-95, 210-211.

[10]. Kang, L.Y. & Zhu, Q.S. (Eds.). (2012). Han Hua Zonglu (Comprehensive Record of Han Dynasty Pictorial Art). Guangxi Normal University Press, 147.

[11]. Xianyang Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology. (2005). Ren Jia Ju Qin Mu. Scientific Publishing House.

[12]. Wang, Z.H. (2018). The theoretical construction and cultural representation of sacred space. Cultural Heritage, (06), 91-98.

[13]. Wang, Z.Q. (1993). The Zhu Shu soul vase of the 9th year of Yanxi in the Eastern Han dynasty. China Cultural Relics Newspaper, 7 November, 3.

[14]. Li, S., & Xuan, X.L. (2019). Baguan In Guanzi 5. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 242.

[15]. Liu. S.Q. & Sun L. (1989). The Tomb with Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs and Murals on Qinglong Mountain, Jinan, Shandong Province. Archaeology, (11), 984-993, 1059-1060.

[16]. Wang, Chong. (1990). Sihui Pian 23. In Lun Heng Jiao Shi. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 972.

[17]. Xun, Qing. (1978). Xun Zi 19, Li Lun. In Zhuzi Jicheng (Collection of Philosophers). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 243.

[18]. Wang, C. (1978). Bozang Pian. In Zhuzi Jicheng 1st ed. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 225.

[19]. Sun, X.D. (1989). Juan 47: Jitong Di 25 [Volume 47: The 25th Chapter on the Meaning of Sacrifices]. In Liji Jijie [Collected Explanations of the Book of Rites]. 1st ed Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 1236-1237.

[20]. Wei, Z. (2020). A re-study on the phenomenon of setting up offerings in Han dynasty tombs and sacrificial utensils. Archaeology, (11), 83-90.

[21]. Ruan, Yuan. (Ed.). (2009). Ji Yi 24. In Shi San Jing Zhu Shu: Qing Jiaqing Ke Ben. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 3456.

[22]. Shandong Provincial Museum. (2015). Yinan Beizhai Han Tomb Portraiture. Cultural Relics Publishing House.

[23]. Ruan, Yuan. (Ed.). (2009). Mao Shi Zhengyi 7. In Shi San Jing Zhu Shu: Qing Jiaqing Ke Ben. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 804.

[24]. Wang, G.Y. (1981). Pottery with Zhu Shu inscriptions from the Guanghe and Yongyuan periods discovered in Han tombs in Baoji City. Cultural Relics, (3).

[25]. Wu, L. & Xue, Y. (1987). The Eastern Han stone relief tomb in Guanzhuang, Mizhi County, Shaanxi. Archaeology, (11), 997-1001.

[26]. Wang, Chong. (1990). Si Wei Pian. In Lun Heng Jiao Shi. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 887.

[27]. Kang, L.Y. & Zhu, Q.S. (Eds.). (2012). Han Hua Zonglu (Comprehensive Record of Han Dynasty Pictorial Art). Guangxi Normal University Press, 147.

[28]. Xin, L.X. (2000). A comprehensive study on Han dynasty stone reliefs. Cultural Relics Publishing House, 323.

[29]. Liu, X. (2008). Shi Gongshi 17. In Bi Y., and Wang X.Q. eds. Shiming Shuzheng Bu. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 188.

[30]. Luo, E.H. (2000). A study on Han dynasty pictorial stone coffins. Acta Archaeological Sinica, (01), 31-62.

[31]. Liu, Y.M. (2012). A study on Han dynasty pictorial stone coffins and their immortal beliefs [PhD dissertation]. Shandong University.

[32]. Wu, H. (2005). Art in Ritual Context (Zheng, Y. et al. trans.). SDX Joint Publishing Company, 102.

[33]. Gao, W. (1998). A Collection of Stone Coffin Paintings of the Han Dynasty in Sichuan. People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, pp. 70-72, figs. 136-139.

[34]. Jiang, S. (1997). A study on Han dynasty que. Journal of Sun Yat-sen University (Social Science Edition), (01), 61-66.

[35]. Sun, J. (2013). Between immortals and mortals, the visible and the invisible: Han dynasty stone reliefs and imitating life. Journal of National Museum of China, (09), 81-117.

[36]. Lin, B.Z., Wang, Y., Chen, A.L., et al. (2018). Excavation report on Tomb M1 of the Mandongpo cliff tomb group in Bishan District, Chongqing. Sichuan Cultural Relics, (01), 23-31.

Cite this article

Ding,M. (2025). The sacredness of Eastern Han Dynasty pictorial stones from the perspective of physicality. Advances in Humanities Research,12(6),60-70.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Humanities Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Zhang, J. (2019). A study on the pictorial narrative of Han dynasty stone reliefs [PhD dissertation]. Wuhan University. https: //doi.org/10.27379/d.cnki.gwhdu.2019.00223

[2]. Wang, Z.H. (2024). How is the de-boundaries sacredness possible? The construction mode of sacred space from the perspective of heaven-human relations. World Religious Cultures, (02), 160-166.

[3]. Li, Q.Q. (2015). Tomb gates and Tian-men: A study on the themes of stone reliefs on Eastern Han tomb gates in northern Shaanxi. Journal of the Arts, (02), 14-24.

[4]. Wu, H. (1989). The Wu Liang Shrine: The Ideology of Early Chinese Pictorial Art. Stanford University Press, 73-217.

[5]. Li, W.X. (2014). The shrine owner paying homage to the immortal messengers of the Queen Mother of the West: A query on the shrine owner being worshipped images in Han dynasty stone reliefs. Ancient Civilizations, 8(02), 68-77, 113-114. https: //doi.org/10.16758/j.cnki.1004-9371.2014.02.016

[6]. Guo, Y.Y. & Zhang, X.Y. (2021). The ethical movement of the transformation of views on death from physicality to embodied subjectivity. Medicine and Philosophy, 42(20), 33-37.

[7]. Ruan, Yuan. (Ed.). (2009). Jiao Te Sheng. In Shi San Jing Zhu Shu: Qing Jiaqing Ke Ben. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 3156.

[8]. Li, W.X. (2012). Physicality expression and pursuit of faith [PhD dissertation]. Shandong University.

[9]. Yang, A.G. (2020). Discovery and research on inscriptions on Han dynasty stone reliefs. Chinese Calligraphy, (12), 80-95, 210-211.

[10]. Kang, L.Y. & Zhu, Q.S. (Eds.). (2012). Han Hua Zonglu (Comprehensive Record of Han Dynasty Pictorial Art). Guangxi Normal University Press, 147.

[11]. Xianyang Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology. (2005). Ren Jia Ju Qin Mu. Scientific Publishing House.

[12]. Wang, Z.H. (2018). The theoretical construction and cultural representation of sacred space. Cultural Heritage, (06), 91-98.

[13]. Wang, Z.Q. (1993). The Zhu Shu soul vase of the 9th year of Yanxi in the Eastern Han dynasty. China Cultural Relics Newspaper, 7 November, 3.

[14]. Li, S., & Xuan, X.L. (2019). Baguan In Guanzi 5. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 242.

[15]. Liu. S.Q. & Sun L. (1989). The Tomb with Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs and Murals on Qinglong Mountain, Jinan, Shandong Province. Archaeology, (11), 984-993, 1059-1060.

[16]. Wang, Chong. (1990). Sihui Pian 23. In Lun Heng Jiao Shi. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 972.

[17]. Xun, Qing. (1978). Xun Zi 19, Li Lun. In Zhuzi Jicheng (Collection of Philosophers). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 243.

[18]. Wang, C. (1978). Bozang Pian. In Zhuzi Jicheng 1st ed. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 225.

[19]. Sun, X.D. (1989). Juan 47: Jitong Di 25 [Volume 47: The 25th Chapter on the Meaning of Sacrifices]. In Liji Jijie [Collected Explanations of the Book of Rites]. 1st ed Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 1236-1237.

[20]. Wei, Z. (2020). A re-study on the phenomenon of setting up offerings in Han dynasty tombs and sacrificial utensils. Archaeology, (11), 83-90.

[21]. Ruan, Yuan. (Ed.). (2009). Ji Yi 24. In Shi San Jing Zhu Shu: Qing Jiaqing Ke Ben. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 3456.

[22]. Shandong Provincial Museum. (2015). Yinan Beizhai Han Tomb Portraiture. Cultural Relics Publishing House.

[23]. Ruan, Yuan. (Ed.). (2009). Mao Shi Zhengyi 7. In Shi San Jing Zhu Shu: Qing Jiaqing Ke Ben. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 804.

[24]. Wang, G.Y. (1981). Pottery with Zhu Shu inscriptions from the Guanghe and Yongyuan periods discovered in Han tombs in Baoji City. Cultural Relics, (3).

[25]. Wu, L. & Xue, Y. (1987). The Eastern Han stone relief tomb in Guanzhuang, Mizhi County, Shaanxi. Archaeology, (11), 997-1001.

[26]. Wang, Chong. (1990). Si Wei Pian. In Lun Heng Jiao Shi. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 887.

[27]. Kang, L.Y. & Zhu, Q.S. (Eds.). (2012). Han Hua Zonglu (Comprehensive Record of Han Dynasty Pictorial Art). Guangxi Normal University Press, 147.

[28]. Xin, L.X. (2000). A comprehensive study on Han dynasty stone reliefs. Cultural Relics Publishing House, 323.

[29]. Liu, X. (2008). Shi Gongshi 17. In Bi Y., and Wang X.Q. eds. Shiming Shuzheng Bu. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 188.

[30]. Luo, E.H. (2000). A study on Han dynasty pictorial stone coffins. Acta Archaeological Sinica, (01), 31-62.

[31]. Liu, Y.M. (2012). A study on Han dynasty pictorial stone coffins and their immortal beliefs [PhD dissertation]. Shandong University.

[32]. Wu, H. (2005). Art in Ritual Context (Zheng, Y. et al. trans.). SDX Joint Publishing Company, 102.

[33]. Gao, W. (1998). A Collection of Stone Coffin Paintings of the Han Dynasty in Sichuan. People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, pp. 70-72, figs. 136-139.

[34]. Jiang, S. (1997). A study on Han dynasty que. Journal of Sun Yat-sen University (Social Science Edition), (01), 61-66.

[35]. Sun, J. (2013). Between immortals and mortals, the visible and the invisible: Han dynasty stone reliefs and imitating life. Journal of National Museum of China, (09), 81-117.

[36]. Lin, B.Z., Wang, Y., Chen, A.L., et al. (2018). Excavation report on Tomb M1 of the Mandongpo cliff tomb group in Bishan District, Chongqing. Sichuan Cultural Relics, (01), 23-31.