1. Picasso’s Poetry

Picasso’s poetry is getting wider recognition for its innovative approach to writing. Although several publications appeared during his lifetime – in art journals and literary reviews– two projects for the publication of all of his poems which he himself had undertaken never came to fruition. It was not until 1989 that his collected writings were compiled and published in one single volume. Picasso’s poetic activity has recently given rise to quite a few studies—some of them quite lengthy, such as Michaël [31] and Rißler-Pipka [35]—and has been the subject of several conferences and exhibitions. Despite all this, overall, his literary contributions still remain largely unknown outside the narrow circle of specialists. Yet, we could say without exaggerating that Picasso’s literary writing was as revolutionary as his plastic work, thus demolishing the usual compartmentalizing of creators as belonging to single categories.

Picasso started writing in 1935, although there are indications that he might have started earlier. This was a difficult moment in his life as he was in the process of separating from his wife Olga Khohklova due to an uncovered secret affair with the young Marie-Thérèse Walter, from whom he was expecting a child. All this eventually resulted in him being blocked from his own studio for a few months. Keeping a distance from the bourgeois environment that had been imposed by his wife for years, Picasso began to live again in a bohemian style and started to put down his thoughts and frustrations in odd sheets of paper. He would announce to his friends that he was ready “to give up everything, painting, sculpture, engraving and poetry to devote himself entirely to ‘singing.’”

This overlap between the beginning of his poetic activity and his personal problems have led some critics to argue, based primarily on the artist’s biography, that his writing had come about as a derivative and compensating substitute in response to a possible artistic block. However, the evolution of his style thereafter shows that it did no consist of a temporary distraction from his artistic practice, but rather that it was closely linked to his continued interest in defiant creative language. His approach to writing might have borrowed certain elements from his surrealist friends whom he rubs shoulders with more frequently during this period, but the outcome was definitely Picassian.

2. Possible Triggers

The first known text by the artist is the one written in Spanish in Boigeloup on April 18, 1935 and the last, of which only a facsimile of the original exists, was also written in Spanish between January 6, 1957 and August 20, 1959. The most intense periods of his literary activity were the years 1935-1936 (during which his pictorial activity decreases) and the years 1939-1941. Even if his writing was not uninterrupted, it co-existed with his plastic work for years, producing in the end– according to current estimates– more than three hundred and fifty poems (among which there are long examples written over several days) and three plays: Le désir attrapé par la queue, Les Quatre Petites Filles and El entierro del Conde de Orgaz. Most of his poems are repeated in several states and variants; if one takes into account not only the last state of each poem but all of their successive stages, the volume of writing would increase considerably.

Picasso wrote in both Spanish and French without giving priority to his native language. Poems written in French even tend to dominate, since there are around two hundred texts in that language, including two of the three plays, compared to one hundred and fifty in Spanish. Even more interesting is the fact that Picasso did not hesitate to mix the two languages and to switch freely from one to the other, each time accomplishing unexpected results. From this point of view, it is not surprising that his first text written in French, following several writings in Spanish, should constitute a reflection on the nature of translation: “if I think in a language and write ‘the dog chases the hare through the woods’ and want to translate this into another language I have to say ‘the table of white wood sinks its paws into the sand and nearly dies of fright knowing itself to be so silly.” As Rißler-Pipka has pointed out, translation does not mean for him just the rendition from one language to the other, but a potential alteration of meaning. What he expresses is the fact, that his thinking itself is different depending on the language. Any connection between the two versions had to be left in the dark.

3. Possible Influences

There is no question that Picasso was aware of some of the writings being published by Surrealists like André Breton, Paul Éluard and others. In her 1981 dissertation, Lydia Gasman outlined the crucial influence they had on his work as a whole. As Rothenberg & Joris have recently explained, for Picasso as for Breton, poetic practice was not restricted to unmediated psychic acts or automatic writing, but consisted instead of careful compositions, often accompanied by revisions—however done rapidly—subjecting the original drafts to a flux of changes, additions, and deletions. There is a certain spontaneity, but it is a reworked spontaneity. Breton called his poems “semi-automatic”.

Molina compared Picasso’s “spontaneous phrases” in his poems to “verbal shots fired while doing tightrope pirouettes”. Through his free verses, Picasso managed to bring forth a world of reminiscences from his childhood and early days in Spain, as if speaking of a golden age, for ever present in his mind even following his later triumphal career. Nevertheless, the artist still kept an eye on his immediate circumstances and surroundings, further enriching his poems with references to the Spanish civil war, the shortages and sufferings during the German occupation of France, his isolation from friends and relatives, etc.

Picasso the writer was as inventive as Picasso the painter. He was not satisfied with an established method, but instead continually experimented with the possibilities afforded by his new material: words became malleable elements in his hands. He engaged in poetic creation with the same ambitious and challenging agenda that he brought to painting. As Gutiérrez-Rexach maintains, he was not only interested in the representation of emotions or in capturing the observed and intuited realities of his time, he also wanted to question the means of representation, its mechanisms, and even the nature of representation itself. He subverted language to expose its limits and in so doing he envisioned a new reality, probably deeper than the commonly perceived reality, only accessible in the poetic realm.

4. Defiant Poet

As in his approach to the visual arts, Picasso the poet is a defiant creator. Picasso’s writing is nomadic in terms of its free flow of words, unhampered by the sedentarizing effects of normative grammar. According to Sabartés, “he want[ed] to use all possible words, verbs and all other garments of language, to provide a graceful decoration, to pull the ends of ready-made sentences and undo them at his pleasure, to play with them, to use them as escape doors, to turn thought around without enduring it, to turn language into a plastic material and to do something that is not similar to the impetuous expression that comes from the lips ... that is why the attractive sing-song of an expression cajoles the pen and takes away the spirit, makes you forget the purpose that one proposes by unintentionally projecting a vision, an act or a suggestion. When that happens to him, when he realizes it, he comes back to himself and does what he can to subject the word to his desire, to turn off its sound, crush it, remove the edges and corners ... He paints with words in lines that are tense like the strings of a harp. In this manner he enjoys putting on paper in the shape of words those images that he would once suggest with plastic creations.”

5. Multiple Versions

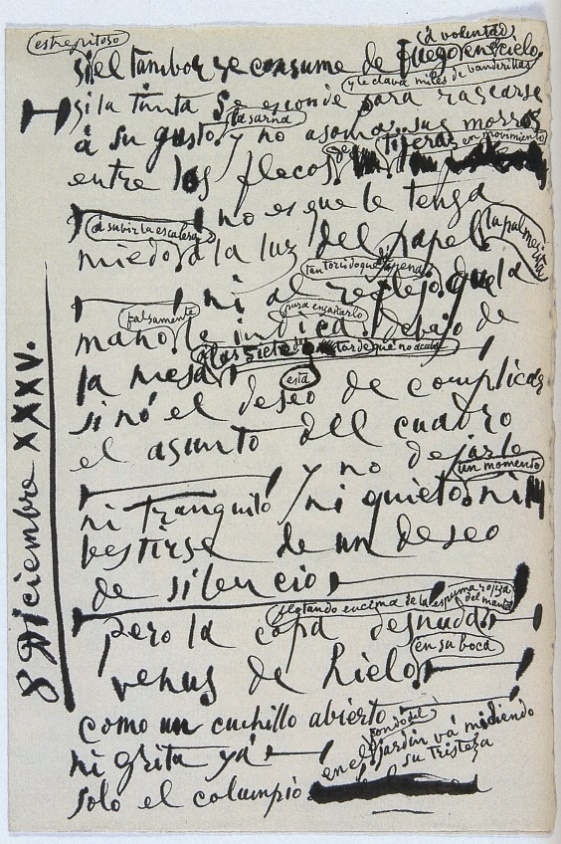

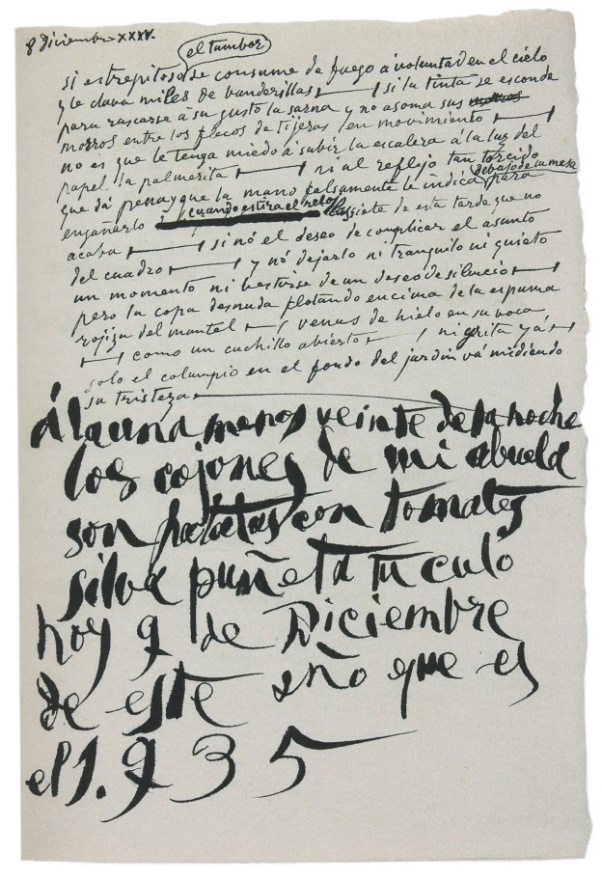

To illustrate Picasso’s poetry, I will use two poems from the two intense periods of literary activity mentioned earlier, one written on December 8, 1935 and another on January 4, 1940. The first one is a good example of how many of his poems went through successive states. He have a sense that this last version in existence is just one more step in an endless chain. This insistence on incompleteness is a specific feature to Picasso’s working practice. He had a horror of anything frozen in time. Indeed, he saw in incompleteness the necessary condition for opening up the possibility of a new perspective. This is how, when Sabartés asked, “And then, what do you do when you have finished the painting? Picasso answered: “Have you ever seen a finished painting? No more a painting than anything else. Woe to you when you say you’re done. Finish a work? Complete a painting? What a stupid thing! To finish means to put an end to an object, to kill it, to take away its soul, to give it the puntilla, to “finish it” as we say here, that is to say to give it what is most annoying for the painter. and for the painting: the coup de grâce.”

Figure 1: si estrepitoso el tambor … (1). OPP.35:070

8 Diciembre XXXV

si estrepitoso el tambor se consume de fuego a voluntad

en el cielo y le clava miles de banderillas

si la tinta se esconde para rascarse

a su gusto la sarna y no asoma sus morros

entre los flecos de tijeras en movimiento

no es que le tenga

miedo a subir la escalera a la luz del papel la palmerita

ni al reflejo tan torcido que da pena que la

mano falsamente le indica debajo de

la mesa para engañarlo a las siete de esta tarde que no acaba

si no el deseo de complicar

el asunto del cuadro

y no dejarlo

ni tranquilo ni quieto un momento ni

vestirse de un deseo

de silencio

pero la copa desnuda flotando encima de la espuma rojiza

del mantel venus de hielo en su boca

como un cuchillo abierto

ni grita ya

solo el columpio en el fondo del jardín va midiendo su tristeza

Figure 2: si estrepitoso el tambor … (2). OPP.35:071

8 Diciembre XXXV

si estrepitoso el tambor se consume de fuego a voluntad en el cielo

y le clava miles de banderillas si la tinta se esconde

para rascarse a su gusto la sarna y no asoma sus

morros entre los flecos de tijeras en movimiento

no es que le tenga miedo a subir la escalera a la luz del

papel la palmerita ni al reflejo tan torcido

que da pena y que la mano falsamente le indica debajo de la mesa para

engañarlo cuando estira el reloj las siete de esta tarde que no

acaba si no el deseo de complicar el asunto

del cuadro y no dejarlo ni tranquilo ni quieto

un momento ni vestirse de un deseo de silencio

pero la copa desnuda flotando encima de la espuma

rojiza del mantel venus de hielo en su boca

como un cuchillo abierto ni grita ya

solo el columpio en el fondo del jardín va midiendo

su tristeza

a la una menos veinte de la noche

los cojones de mi abuela

son patatas con tomates

silba puñeta tu culo

hoy 9 de Diciembre

de este año que es

el 1.935

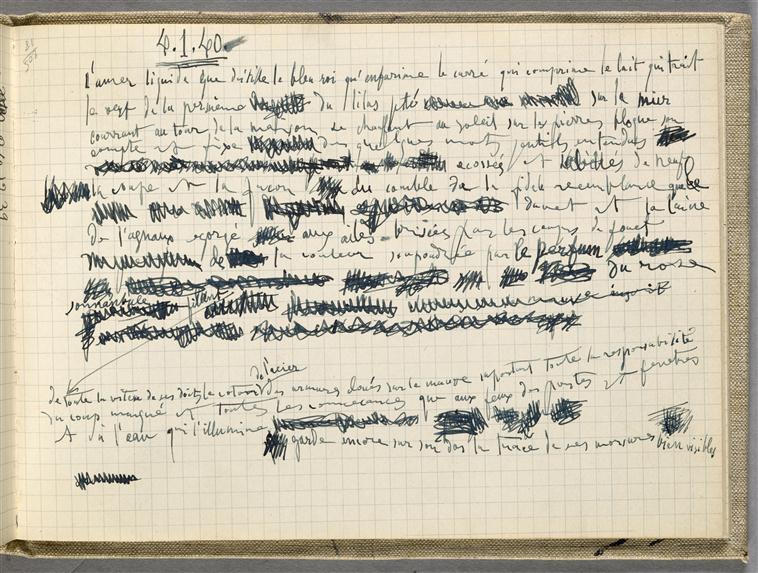

Figure 3: l’amer liquide. OPP.40:257

4.1.40

l’amer liquide que distille le bleu roi qu’enfarine le carré qui comprime le lait qui trait

le vert de la persienne du lilas jeté sur le mur

courant autour de la maison se chauffant au soleil sur les pierres bloque son

compte et fixe dans quelques mots gentils entendus

écossés et habillés de neuf

la coupe et la façon du comble de la fidèle ressemblance que le

duvet et la laine

de l’agneau égorgé aux ailes brisées par les coups de fouet

de la couleur saupoudrée par le parfum du rose

somnambule filant

de toute la vitesse de ses doigts le coton de l’acier des armures clouées sur le mauve supportant

toute la responsabilité

du coup marqué et toutes les conséquences qu’aux feux des portes et fenêtres

et à l’eau qui l’illumine garde encore sur son dos la trace de ses morsures bien visibles

6. Multiple Connectors

One thing that immediately stands out as we peruse the poems is the presence of multiple connectors (si, y, que, ni, de, et, qui, du, etc.,). The frequency of these elements makes them lose any causal or subordinating effects they have in traditional syntactical constructions to become pure accelerators of action, a way of getting from one thing to the next; its multiplicity immediately overcomes the (mis)use (as brake) of these these connectors when present singly, altering them to function as dividers, separators, creators of dialectical or ontological differentiations between two terms, and thus as destroyers of all kinds of dualisms. Rothenberg and Joris point out that the multiple conjunctions do not set up one-to-one relations between the terms they align, but function vectorially, pointing to drifting spaces outside and beyond those terms. As Deleuze writes: “The ‘and’ is not even a specific relation or conjunction, it is that which subtends all relations, the path of all relations, which makes relations shoot outside their terms and outside the set of their terms, and outside everything which could be determined as Being.” Other linking elements such as the preposition “de” play a similar role. Their rhizomatic layout linking wildly heterogeneous series of terms subverts any of its single or double genitive functions, forcing the reader to eventually relinquish causal/grammatical readings. In fact, it is the relinquishing of any resolution to locate the specific relationship of the combined units that leads the reader to experience an indefinite chain of derivations in an endless move forward.

si estrepitoso el tambor se consume de fuego a voluntad en el cielo

y le clava miles de banderillas

si la tinta se esconde para rascarse

a su gusto la sarna y no asoma sus morros

entre los flecos de tijeras en movimiento

no es que le tenga

miedo a subir la escalera a la luz del papel la palmerita

ni al reflejo tan torcido que da pena que la

mano falsamente le indica debajo de

la mesa para engañarlo a las siete de esta tarde que no acaba

si no el deseo de complicar

el asunto del cuadro

y no dejarlo

ni tranquilo ni quieto un momento ni

vestirse de un deseo

de silencio

pero la copa desnuda flotando encima de la espuma rojiza

del mantel venus de hielo en su boca

como un cuchillo abierto

ni grita ya

solo el columpio en el fondo del jardín va midiendo su tristeza

si estrepitoso el tambor se consume de fuego a voluntad en el cielo

y le clava miles de banderillas si la tinta se esconde

para rascarse a su gusto la sarna y no asoma sus

morros entre los flecos de tijeras en movimiento

no es que le tenga miedo a subir la escalera a la luz del

papel la palmerita ni al reflejo tan torcido

que da pena y que la mano falsamente le indica debajo de la mesa para

engañarlo cuando estira el reloj las siete de esta tarde que no

acaba si no el deseo de complicar el asunto

del cuadro y no dejarlo ni tranquilo ni quieto

un momento ni vestirse de un deseo de silencio

pero la copa desnuda flotando encima de la espuma

rojiza del mantel venus de hielo en su boca

como un cuchillo abierto ni grita ya

solo el columpio en el fondo del jardín va midiendo

su tristeza

a la una menos veinte de la noche

los cojones de mi abuela

son patatas con tomates

silba puñeta tu culo

hoy 9 de Diciembre

de este año que es

el 1.935

l’amer liquide que distille le bleu roi qu’enfarine le carré qui comprime le lait qui trait

le vert de la persienne du lilas jeté sur le mur

courant autour de la maison se chauffant au soleil sur les pierres bloque son

compte et fixe dans quelques mots gentils entendus

écossés et habillés de neuf

la coupe et la façon du comble de la fidèle ressemblance que le

duvet et la laine

de l’agneau égorgé aux ailes brisées par les coups de fouet

de la couleur saupoudrée par le parfum du rose

somnambule filant

de toute la vitesse de ses doigts le coton de l’acier des armures clouées sur le mauve supportant

toute la responsabilité

du coup marqué et toutes les conséquences qu’aux feux des portes et fenêtres

et à l’eau qui l’illumine garde encore sur son dos la trace de ses morsures bien visibles

7. Graphic Elements

Another noticeable feature of these manuscripts are the number of graphic elements that appear, not to mention his particularly playful calligraphy. Caparrós mentions that Picasso’s use of words beyond the strictly linguistic level to which literature would have subjected it, to expand its value as a sign on different semiotic levels, iconic, visual, phonetic. Picasso, consistent with himself, explores in the space of the word the bridges and potentialities that emerge towards other artistic expressions. Here the intention to break the conditions inherent to each representative, iconic or linguistic system reappears. Thus, when the word is written – in the literal sense, with letters – it can be a drawing, it can be transformed into calligraphy, into painting, into plastic expression. If the word is said, that is, if it is stated orally, it becomes an arbitrary sound (almost always), it emits a sound like music does, it is rhythm, cadence, foreign to the conventions imposed by spelling and unattainable by grammar.

Picasso’s writing is perpetually in the making, constantly evolving; and the many alterations he made to the poems are often highlighted by dashes (—), word bubbles (< >), inserts ([ ]), erasures (XXX), etc. As Cowling [11] noticed. “a glance at the manuscripts reveals that he was attentive to the look and lay-out of the pages, relishing the dramatic impact of such things as variations in the size and style of the script, changes in the flow of ink … contrasts between letters, numbers, dividing lines and the special punctuation marks he favored, different systems for crossing-out and large blots of ink.” The presence of all these graphic elements combined with the shifting and often playful calligraphy often give the draft the appearance of an illuminated manuscript. Nevertheless, to say that Picasso’s poems constitute visual compositions does not entail that the arrangement of the text should not be evaluated linguistically. We will show that the method he used in his writings is essentially syntactic in nature, although the manner in which he arranged the constituents in his poems could very well derive from the lessons learned during his involvement with the cubist collage.

Bois [5] suggested that, during Cubism, Picasso played with the realization of “the value of the minimum sign.” He seized on the awareness that a mere handful of signs “none referring univocally to a referent” had the potential to provide multiple significations. However, the cubist collage also brought attention to the idiosyncrasy of artistic representation and the role it had in the production of that reality, as Cottington [10] has emphasized. Cubism demands from its audience the necessity to engage in a relationship with the artistic endeavor as the viewer/reader is encouraged to find his/her own meaning and understanding from the specific depiction of the subject.

si

en el cielo

— si la tinta se esconde para rascarse

a su gusto

entre los flecos [de] XXX

— no es que le tenga

miedo a la luz del papel

— ni al reflejo

mano

la mesa

si no el deseo de complicar

el asunto del cuadro

— y no dejarlo

ni tranquilo ni quieto

vestirse de un deseo

de silencio —

— pero la copa desnuda del mantel> XXX — venus de hielo como un cuchillo abierto — ni grita ya — solo el columpio XXX en el si estrepitoso y le clava miles de banderillas — si la tinta se esconde para rascarse a su gusto la sarna y no asoma sus morros entre los flecos de tijeras en movimiento — no es que le tenga miedo a subir la escalera a la luz del papel la palmerita — ni al reflejo tan torcido que da pena y que la mano falsamente le indica engañarlo XXX [cuando estira el reloj] las siete de esta tarde que no acaba — si no el deseo de complicar el asunto del cuadro — y no dejarlo ni tranquilo ni quieto un momento — ni vestirse de un deseo de silencio — pero la copa desnuda flotando encima de la espuma rojiza del mantel — venus de hielo en su boca — como un cuchillo abierto — ni grita ya — solo el columpio en el fondo del jardín va midiendo su tristeza — a la una menos veinte de la noche los cojones de mi abuela son patatas con tomates silba puñeta tu culo hoy 9 de Diciembre de este año que es el 1.935 l’amer liquide que distille le bleu roi qu’enfarine le carré qui comprime le lait qui trait] le vert de la persienne XXX du lilas jeté XXX sur le mur [courant autour de la maison se chauffant au soleil sur les pierres bloque son compte et fixe XXX dans quelques mots gentils entendus XXX XXX écossés et habillés de neuf la coupe et la façon XXX du comble de la fidèle ressemblance que [le] XXX duvet et la laine de l’agneau égorgé XXX aux ailes brisées par les coups de fouet XXX de XXX la couleur saupoudrée par le parfum XXX [du rose] XXX [somnambule filant] [de toute la vitesse de ses doigts le coton supportant toute la responsabilité du coup marqué et toutes les conséquences qu’aux feux des portes et fenêtres et à l’eau qui l’illumine XXX [garde encore sur son dos la trace de ses morsures bien visibles]] As was the case with papier collés, lexical items in Picasso’s poems do not lose their physical presence as they enter the realm of signification; they are equally valid as material elements, providing tonality and rhythm to the lines of the poem, as the color and texture of the pasted papers did in the cubist composition. The way in which his words are potentially combined in the writing/reading process crucially depends on their visual distribution on the page, and this in turn is emphasized by the graphic elements Picasso includes. The paradox of papier collés imposed a reality in imagery abstracted from reality. But this was a reality that was created—a conception and not always a perception. We will see that the artist pursues a similar goal with his poetry. Rothenberg & Joris cite Bernadac, who brings to our attention how Picasso uses “this new ‘plastic material’ [of language] ... chipping, pulverizing, modeling this ‘verbal clay,’ varying combinations of phrases, combining words, either by phonic opposition, repetition, or by an audacious metaphorical system, the seeming absurdity of which corresponds in fact to an internal and personal logic ... Lawless writing, disregardful of syntax or rationality, but which follows the incessant string of images and sensations that passed through his head … [One observes] various rearrangements of words and phrases from one text to another, “as if he were moving paper cutouts in a painting or drawing.” Incidentally, also similar to his artistic practice, is Picasso’s tendency to use any support he had handy to jot down his poems: from letterhead to envelopes, from sheets of colored paper to pieces cut out of a newspaper, even toilet paper. But on rare occasions, he used sheets of Arches paper, a support he was particularly fond of and which he also used for his drawings at that same time: “Luckily, he says, I was able to get my hands on a stock of splendid Japanese paper. This paper seduced me … It is so thick that, even by scratching it, you barely touch its deep layers.” One could then easily imagine that Picasso’s manuscripts would be teeming with sketches and all sorts of colorful enhancements. However, there are only a few of those manuscripts that are accompanied by drawings or engravings. The majority of them exclusively display texts crossed out and rewritten many times as one would expect from a writer’s draft. Indeed, it is surprising, from the point of view of the genesis of the work that any effort at pictorial representation was set aside. The marks he scribbled on the sides are marginal indexical elements intended to indicate the adjunctive nature of the text they serve to identify. Yet, this does not take way from the aesthetic value of those manuscripts, which can be enjoyed as much for their striking visual appearance as for the content of their text. 8. Writing Badly Rothenberg & Joris have pointed out how Picasso purposely practiced a complete obliteration of punctuation marks. This gives his poems the feel of a wide-open field, a smooth, non-striated space, or blocks of space, through or along which one can travel unchecked, free to choose one’s own moment of rest, free to create one’s own rhythms of reading—an exhilarating and liberating, dizzying and breathtaking dérive. His texts indeed have their own dynamic, which does not conform to pre-established orthographic or grammatical rules: there are no punctuations, spelling remains unchecked, a subordinate condition is rarely followed by its main clause, a raised question is left suspended, a sentence is stopped by another which intersperses its meaning. Picasso ironically advocates for writing “poorly done.” He was quoted as saying: “If only one could write wrong! Today writers have limited themselves to moving around words somewhat while respecting the syntax. It would be necessary to have a perfect knowledge of semantics and to write badly.” Language is, by nature, a system of conventions that guarantees communication, but the ideal of modern art tends to be the opposite. It requires singularizing, breaking conventions in order to surprise, breaking expectations. “La surprise est le plus grand ressort nouveau”, Apollinaire had declared in 1918 (L’esprit noveau). Picasso indeed grasps the true nature of literature which seeks to push the boundaries of verbal communication, thus inventing a new language within language by creating a “new” syntax. Caparrós comments that it is about not using anything in a strict literal sense, so that the familiar becomes strange. Only in this way does the aesthetic experience acquire its full value and, what is more important, allows us to contemplate reality with clean eyes. In Picasso’s view, style manages to dilute our attention on the how without paying attention to the what. “Writing badly,” from this perspective, is the most effective way to dispel such mirages and be able to directly reach the meanings. To “write badly” in the sense proposed above one would have to rely more deeply on lexical semantics, that is, one would have to be familiar with the rich meanings of words and their multiple connotations. Picasso wanted to free himself from “the tyranny of language,” but this is truly impossible. After all, we share a language because we all share the same recursive minimal system. The only possible transgression is to let meaning flow through the cracks of syntax. 9. Adjunctive Writing As pointed out in Mallen [28], the text that Picasso introduces with graphic insertions is purposely left differentiated (often placed at a different level, or in the margins, etc.), as if they were footnoted “afterthoughts” to the already validated text. In fact, it is sometimes quite a task for the editor of these poems to decide exactly where the added text must be incorporated, as the writer intentionally leaves this detail ambiguous. The reader is equally left to choose whether to follow the suggested insertions or to continue with the original text, ignoring the later additions. si [AP estrepitoso] el tambor se consume de fuego [PP a voluntad] en el cielo] [CP y le clava miles de banderillas] — [CP si la tinta se esconde para rascarse a su gusto [NP la sarna] y no asoma sus morros] entre los flecos [PP de] XXX [NP tijeras en movimiento] XXX — no es que le tenga miedo [CP a subir la escalera] a la luz del papel [NP la palmerita] — ni al reflejo [AP tan torcido que da pena] que la mano [AP falsamente] le indica debajo de la mesa [CP para engañarlo] [PP a las siete de esta tarde que no acaba] — si no el deseo de complicar] el asunto del cuadro — y no dejarlo ni tranquilo ni quieto [NP un momento] — ni XXX vestirse de un deseo de silencio — — pero la copa desnuda [VP flotando encima de la espuma rojiza del mantel] XXX — venus de hielo [PP en su boca] — como un cuchillo abierto — ni grita ya — solo el columpio XXX [PP en el [NP fondo del] jardín va midiendo su tristeza] si estrepitoso [NP el tambor] se consume de fuego a voluntad en el cielo y le clava miles de banderillas — si la tinta se esconde para rascarse a su gusto la sarna y no asoma sus morros entre los flecos de tijeras en movimiento — no es que le tenga miedo a subir la escalera a la luz del papel la palmerita — ni al reflejo tan torcido que da pena y que la mano falsamente le indica [PP debajo de la mesa] para engañarlo XXX [CP cuando estira el reloj] las siete de esta tarde que no acaba — si no el deseo de complicar el asunto del cuadro — y no dejarlo ni tranquilo ni quieto un momento — ni vestirse de un deseo de silencio — pero la copa desnuda flotando encima de la espuma rojiza del mantel — venus de hielo en su boca — como un cuchillo abierto — ni grita ya — solo el columpio en el fondo del jardín va midiendo su tristeza — a la una menos veinte de la noche los cojones de mi abuela son patatas con tomates silba puñeta tu culo hoy 9 de Diciembre de este año que es el 1.935 [NP l’amer liquide que distille le bleu roi qu’enfarine le carré qui comprime le lait qui trait] [NP le vert de la persienne] XXX [PP du lilas jeté] XXX [PP sur le mur] [VP courant autour de la maison se chauffant au soleil sur les pierres bloque son compte] [CP et fixe XXX [PP dans quelques mots gentils entendus]] XXX XXX [AP écossés et habillés de neuf] la coupe et la façon XXX [PP du comble de la fidèle ressemblance que [DP le] XXX [NP duvet] et [NP la laine] [PP de l’agneau égorgé] XXX [PP aux ailes brisées par les coups de fouet] XXX de XXX [NP la couleur saupoudrée par le parfum] XXX [PP du rose] XXX [AP somnambule filant] [PP de toute la vitesse de ses doigts le coton [PP de l’acier] des armures clouées sur le mauve supportant toute la responsabilité [PP du coup marqué et toutes les conséquences qu’aux feux des portes et fenêtres et à l’ eau qui l’ illumine XXX [VP garde encore sur son dos la trace de ses morsures bien visibles]] Phrases link to each other in fluctuant, reversible attachments, intentionally left tentative and ambiguous, open to potential deletions and insertions as the poems undergo revisions, just as pieces of pasted paper were precariously pinned to the support in the cubist papier collé and were left opened to the possibility of being removed. What is even more fascinating is that the grammatical function of these inserts tends to be adjunctive. Thus, Picasso seems to be indicating that there is a preeminence of information-based processing over syntactic processing, as the attachment of new elements creates ambiguity and displaces the topic of discourse. The core principles or rather the practical engines of those words in the poem are a nonstop process of connectivity and heterogeneity along the entire semiotic chains of the text, the characteristics of rhizomatic writing. The way this plays itself out in Picasso’s poems can be traced not only in the heterogeneity of the objects, affects, phenomena, concepts, sensations, vocabularies etcetera that can and do enter the writing at any given point, but mainly at the level of the assembling of these heterogeneities: eschewing syntax and its hierarchical clausal structures, the writing jumps back and forth through paratactic relations between terms on a “plane of consistency” that produce concatenations held together (and simultaneously separated) either by pure mental and spatial metonymical juxtapositions enhanced by the endless play of connectors/separators. In standard sentence construction, languages clearly identify expressions as selected arguments by positional or morphological marking. This identification is critical to determine how they relate to the main predicate of a sentence. By contrast, adjuncts tend not be selected by the nucleus of the sentence. In current syntactic theory, adjuncts are modifiers which freely attach at a separate level than arguments in the sentence structure and provide circumstantial information pertaining to the nucleus of the phrase and its relation to both its complement and specifier. Ernst [15] argues that the major determinant of an adjunct’s distribution is the aggregate effect of its lexicosemantic representation and the way it combines with other semantic elements. This means that the lexical entry for an adjunct may be underspecified, so that it may interact with different semantic objects according to different compositional rules, producing the typical ambiguities. He does assume that adjuncts may sometimes select for a specific type of semantic argument, namely, a proposition or an event (as well as a possible second argument), with particular additional properties. The object thus formed by compounding the adjunct and its argument would also be of a particular semantic type. When semantic composition takes place, all lexicosemantic requirements are fulfilled and the sentence is parsed as grammatical. In Picasso’s writing, we see that the different adjunct phrases interact with other constituents in the poem in strings of metaphoric combinations, often contradictory, in the two selected poems, for instance, relating both to a bullfight spectacle and the act of writing itself. The apparently random attachment of adjunctive phrases in his poems generate a range of heterogeneous interpretations which is triggered by numerous, reversible interconnections between the lexical items heading those phrases. Multiple phrasal constituents are combined and left “unattached” for the reader to interpret. The interpretation is directed by a chain of semantic coindexations which is characterized by its multidirectional instability, as any of the terms in the chain could become its head. si en el cielo — si la tinta se esconde para rascarse a su gusto entre los flecos2 [de] XXX — no es que le tenga1/3 miedo 3 a la luz del papel — ni al reflejo4 mano5 la mesa [NP l’amer liquide que distille le bleu roi qu’enfarine le carré qui comprime le lait qui trait]1 [NP le vert de la persienne]1 XXX [PP du lilas jeté]1 XXX [PP sur le mur] [VP courant autour de la maison se chauffant au soleil sur les pierres bloque son compte]1 [CP et fixe XXX [PP dans [NP quelques mots gentils entendus]2] XXX XXX [AP écossés et habillés de neuf]2 As Gutiérrez-Rexach notes, a tension emerges in the connection between syntactic and semantic ambiguity. Adding new terms creates a potential new parsing or syntactic analysis of the sequence that modifies or contradicts the interpretation of the previous parsing. Sabartés, who witnessed the creation of many of these texts, noted the kaleidoscopic impression provided by Picasso’s writings, which he attributes to the same desire that presides in his artistic work, namely to relate and interpret most of the things he knows. His descriptions, starting from a reality or an image, set in motion a mechanism through which new relationships arise. Pablo’s companion, Françoise Gilot noted that he was interested in establishing relationships that are little attended to among all the things he names. He is not guided by harmony, but precisely by the tension between things. It is about putting everything in motion, through opposing forces: “What interests me is to set up what you might call the rapports de grand écart—the most unexpected relationship possible between the things I want to speak about, because there is a certain difficulty in establishing the relationships in just that way, and in that difficulty there is an interest, and in that interest there’s a certain tension and for me that tension is a lot more important than the stable equilibrium of harmony, which doesn’t interest me at all.” Breton was aware as well—or seems to have been—that the actual process of the poems was not linear—all moving in the same direction—but that the written—the handwritten—works were circular or else, like palimpsests, were reaching out in all directions. A very salient constant in Picasso’s poetry is the accumulation of images. This can certainly be related to the collage techniques common in Cubism but, again, goes beyond a mere transposition of a technique from one creative realm to another. In line with the overarching goal of creating new dimensions of reality, images are connected by syntactic accumulation, challenging the reader to find the relevant connective thread or just even a common thread. Images are sometimes loosely connected by intersecting semantic fields or cognitively evoking powerful metaphors. In the end, what we find is a dance of language rather than of the things to which the words allude. He writes: “A wave that never tires of foaming at the surface, like color or like a rainbow of colors with names (it seems) spoken almost lovingly. A risky procession of disparate objects designated by words, but which, despite the intensity of their presence, are only words, billiard balls that roll and bump, launched regularly into absurd adventures, free reining only at the level of utterance, which seems to vouch for and refer to a reality, one that eventually becomes confusingly inane. A kind of psalmody in which the impossible is often signified, in which only the clusters of vocables count, brought into play and calling to each other, occasionally to the point of attack. To virtually make happen that which reasonably could not, but which takes form thanks to an assertion that must, one might say, be believed at its word; such is the astounding power with which we find this type of writing, at each instant, to be gifted.” Creating three-dimensionality from a two-dimensional surface had been one of the main goals of Cubism in painting. In poetry, Picasso carries this concern one step further, to a higher level of abstraction. In his poetry, we move from the three-dimensional space and the three dimensions of spatial perception to the many-dimensionality of the propositional or conceptual space, the space of meaning. As Gutiérrez-Rexach reminds us, recent trends such as Potts [34] advocate the idea of decomposing meaning in different layers, each with its own nature and requirements. Wittgenstein states in his notebooks that distrust of grammar is the first condition for philosophizing. Well, something similar is found in Picasso’s literary writing. 10. Syntax in Suspension To use an expression Michaël cites from Deluze, in Picasso “language is seized with a delirium, which makes it precisely emerge from its furrows,” thus breaking the coherences dictated by the rules of syntax. In Picasso, we appreciate an attempt to use available syntactic rules and conventions to put the syntax in suspension thus gaining full expressivity. Words are inserted and left hanging in the poem, displayed on top of a line or on the margins. This is not just a typographical trick to suggest a certain shape or form. The insertions (and omissions) create grammatical multi-dimensionality at the syntactic and semantic levels. One immediate effect of this strategy is the multiplication of the conceptual space, creating the possibility of several interpretations. By adding or suppressing words or phrases, Picasso managed to change the meaning of a structure, multiplying its denotative and connotative content. What Picasso seems to be hinting at is the impossibility of univocal parsing or the preponderance of massive ambiguity. We know that human languages differ from logical and mathematical languages in allowing ambiguity. Syntax conspires with other grammatical means (prosody, intonation) to avoid such ambiguity. Picasso seems to be telling us that we need to force syntax to fail in order to reach a poetic stage, free of the strictures of unambiguous parsing. Adding new terms multiplies syntactic complexity and makes the syntactic derivation “crash”, in Chomsky’s [9] terms. Meaning has to be rescued from the ashes of such syntactic failure. Sometimes recovering meaning is not possible and the sequence appears to be almost non-sensical, from a conventional or standard semantic/logical point of view. Alternatively, the reader may become lost in a galaxy or constellation of potential interpretations, for which conventional syntax has ceased to be a guide. In this respect, As Gutiérrez-Rexach has noted, Picasso would question the logician Willard Quine’s famous statement “meaning grows on the grammar tree”. For Picasso, meaning grows through mechanisms allowed by the adjoined elements in the grammar tree. A new realm of meaning, beyond the logical or linguistic meaning, emerges when the parsing of the syntax is put in suspension. Following Jackendoff and Wittenberg [20], we assume that the complex linguistic configurations in Picasso’s surrealist poetry display many symptoms of lower levels of linguistic hierarchy. More concretely, we can adopt an autonomous semantic interpretation for these appositive structures that go along with those propose by the Simpler Syntax Hypothesis of Culicover [12] and Culicover and Jackendoff [13]: Autonomous Semantics Phrase and sentence meanings are composed from the meanings of the words plus independent principles for constructing meanings, only some of which correlate with syntactic structure. Simpler Syntax Hypothesis (SSH) Syntactic structure is only as complex as it needs to be to guide interpretation. The most explanatory theory is one that imputes the minimum syntactic structure necessary to mediate between phonology and meaning. The Simpler Syntax Hypothesis entails a view of the syntax–semantics interface that differs significantly from the standard view of Fregean compositionality. Simpler Syntax contends that syntactic structure is only as complex as it needs to be to guide interpretation; it does not hold to the stricter standard view that every aspect of interpretation corresponds to some distinct basic element in the configuration. It also promotes the view that some meaning is strictly compositional and some is constructional. Thus, some cases of parataxis need not be located in a particular syntactic element, but may be a property of the syntactic configuration as a whole. 11. Compositionality As Michaël has pointed out, for Picasso writing to a combinatorial practice. In other words, Picasso uses connecting elements and insertions intended to serve as markers simultaneously separating and combining different conceptual domains that reach an alternative dimension as they come in contact. Picasso combined words as he did with numbers, changing their arrangements, using them as elements that are both independent but which make sense in the series as a whole. One of the main tenets of linguistic interpretation is the principle of compositionality, stated explicitly by the German logician Gottlob Frege. This principle states that the meaning of a sequence or expression is a function from the meaning of its parts and the way in which they are combined. It is alleged to be a core principle of the composition of meaning both in logical and in natural languages, after the work of Richard Montague and his followers. In his pursuit of a new language, capable of denoting new semantic realms or realities, Picasso deliberately plays with the compositionality principle. More specifically, he seems to go from compositionality to multicompositionality, where items are allowed to combine almost freely, giving rise to multiple interpretations. The lines of text connect different semantic fields or mental spaces in Fauconnier’s [17] terms. Together they represent the free flow of ideas in the poet’s mind before writing. Images belonging to one space or field become mixed with other images from another field. The intruding images became predominant, and the outcome is a new dominant field or space which, in turn, is also intruded upon by images from another mental space. Thus, image transition is displayed like a chain or domino of concatenating spaces. It seems clear that Picasso appreciates in language the ability to transport us to the conceptual domain beyond the purely referential. TO SAY, written in capital letters, or its equivalent name, become at this point the painter’s goal: “Je veux DIRE le nu. Je ne veux pas faire un nu comme un nu. Je veux seulement DIRE sein, DIRE pied, DIRE main, ventre. Trouver le moyen de le DIRE, et ça suffit. Je ne veux pas peindre le nu de la tête aux pieds. Mais arriver à DIRE. Voilà ce que je veux. Un seul mot suffit quand on en parle. Ici, un seul regard, et le nu te dit ce qu’il est, sans phrases ... Il faut que tu donnes à celui qui regarde le moyen de faire le nu lui-même avec ses yeux.” There is no shortage of verbs in his poems, generally in a paratactic function or free of hierarchies, but what dominates our attention is the accumulation of appositive constituents in long enumerations, the diversification of things (nouns) that revolve around certain fields. The predominance of these nominal goes together with a rejection of the narrative and the descriptive, that is, from the verbal and the adjectival. We could identify it with the chose signifiée, which is consolidated as the building key, capable of evoking the object. It is not the external referent, the objective thing, but its artistic correlate that plays a crucial role, that is, the poetic signified. Once again Picasso imposes a distance between the real object and the created object as he did in Cubism. Where named things manage to unfold their truth is not under the conditions imposed by nature, but in the free medium of the poem. As Picasso recognized, the juggling of syntactic constituents only serves to enhance the semantic interconnections between words in his poems: “Only I have not yet managed to use words without depending on their meaning.” He admitted that he had prepared for his poems “a palette of words” as he set about composing his texts. He was fully aware of the polysemy of words: “Blue. What does blue mean? There are thousands of sensations that we call blue. The blue of the packet of Gauloises … in this case we can say that the eyes are a Gauloises blue, or on the contrary, as we do in Paris, we can say that a steak is blue when we want to say red. This is what I often did when I tried to write poems.” In his poems, he tried to take advantage of this fact, freeing his words from the standard syntactic use without worrying that this would lead to a distortion of ordinary language, because the final goal was precisely to have “reality … torn apart in every sense of the word.”

References

[1]. Apollinaire, G. (1918) “L’esprit noveau et les poétes”. Mércure de France 130.491 (December).

[2]. Baldassari, A. (2005) The Surrealist Picasso. New York: Random House.

[3]. Bernadac, M-L. (1989) “Le crayon qui parle.” Picasso poète. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux.

[4]. Bernadac, M-L. (1989) “La peinture à l’estomac: le thème de la nourriture dans les écrits de Picasso.” pp. 22–29. In: J. Sutherland, M-L. Bernadac & C. Piot (Eds.). Picasso. Écrits. Paris: Réunion des musees nationaux / Gallimard.

[5]. Bois, Y A. (1987) “Kahnweiler’s lesson.” Répresentations. 18. pp. 33–68.

[6]. Brassaï. (1969) Conversations avec Picasso. Paris : Gallimard.

[7]. Breton, A. (1988). Mad Love. New York: Bison Books.

[8]. Caparrós Esperante, L. (2019). “‘Dire le un’: Poesía y referencialidad en Pablo Picasso.” Anales de la Literatura Española Contemporanea. (January). 44.1 pp. 5-26.

[9]. Chomsky, N. (1995) The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

[10]. Cottington, D. (1998) Movements in Modern Art: Cubism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

[11]. Cowling, E. (2002) Picasso: Style and Meaning. New York, NY: Phaidon.

[12]. Culicover, P. (2016) “Parataxis and Simpler Syntax.” Ms. The Ohio State University and Eberhard-Karls Universität, Tübingen

[13]. Culicover, P. and R. Jackendoff (2005) Simpler Syntax. Oxford : Oxford University Press.

[14]. Deleuze, G. and C. Parnet. (1987) Dialogues. New York: Columbia University Press.

[15]. Ernst, Thomas. The Syntax of Adjuncts. (2004) Cambridge University Press.

[16]. Fernández Molina, A. (1988) Picasso, Escritor. Madrid: Prensa y Ediciones Iberoamericanas.

[17]. Fauconnier, G. (1985). Mental spaces: Aspects of meaning construction in natural language. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

[18]. Gilot, F. and C. Lake. 1964 Life with Picasso. New York: McGraw-Hill.

[19]. Gutiérrez-Rexach, J. (2012) “A linguistic approach to the poetry of Pablo Picasso”. pp. 89-104. In: N. Rißler-Pipka & G. Wild (eds.). Picasso – Poesie – Poetik / Picasso, his Poetry and Poetics. Aachen: Shaker Verlag.

[20]. Jackendoff, R. and E. Wittenberg (2014) “What You Can Say Without Syntax: A Hierarchy of Grammatical Complexity”. pp. 65–82. Frederick J. Newmeyer and Laurel B. Preston. (eds.) Measuring Grammatical Complexity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[21]. Joris, P. (2001) “The Nomadism of Picasso”. pp. 25–28. In: Jerome Rothenberg and Pierre Joris (Eds.). The Burial of the Count of Orgaz and Other Poems. Cambridge, MA: Exact Change Publishers.

[22]. Laporte, G. (1974) El amor secreto de Picasso. Barcelona: Euros.

[23]. Leiris, M. (2001) “Afterword.“ pp. 311-316. In J. Rothenberg and P. Joris (Eds.). The Burial of the Count of Orgaz and Other Poems. Cambridge, MA: Exact Change Publishers.

[24]. Mallen, E. (2923) Online Picasso Project (OPP). Retrieved from http:picasso.shsu.edu.

[25]. Mallen, E. (2018) “Parataxis and Interface Rules in Pablo Picasso’s Poetry." Interdisciplinary Journal for Germanic Linguistics & Semiotic Analysis. No. 23.1. pp. 73-111. Spring.

[26]. Mallen, E. (2015) “The Fichtean Anstoß and Pablo Picasso's Poetry.” Revista Académica liLETRAd, No. 1. pp. 251-261. Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla..

[27]. Mallen. (2012). “La poesía simpatética de Pablo Picasso.” pp. 105-140. In: N. Rißler-Pipka & G. Wild (eds.). Picasso – Poesie – Poetik / Picasso, his Poetry and Poetics. Aachen: Shaker Verlag.

[28]. Mallen, E. (2009). "The Multilineal Poetry of Pablo Picasso." Interdisciplinary Journal for Germanic Linguistics & Semiotic Analysis No. 14.2. pp. 163-202. Spring.

[29]. Michaël, A. (2015) “Picasso ou le plaisir de l’écriture et quelques résonances steiniennes.” Revoir Picasso. 28 mars, pp. 1-5.

[30]. Michaël, A. (2011) “Picasso poète: Une expérimentation permanente.” Études 9. (Tome 415), pp. 219-230.

[31]. Michaël, A. (2008) Picasso poète. Paris: Beux-arts de Paris.

[32]. Michaël, A. (2000) “Dans le laboratoire de l’ecriture de Picasso: presentation d’un dossier génétique.” Genesis. 15. pp. 11-28.

[33]. Parmelin, H. (2013) Picasso dit ... suivi de Picasso sur la place. París: Les Belles Lettres.

[34]. Potts, C. (2005) The Logic of Conventional Implicatures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[35]. Rißler-Pipka, N: (2015) Picassos schriftstellerisches Werk. Passagen zwischen Bild und Text, Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

[36]. Rothenberg, J. and P. Joris (Eds.). (2004) The Burial of the Count of Orgaz and Other Poems. Cambridge, MA: Exact Change Publishers.

[37]. Sabartés, J. (1953) Picasso: Retratos y recuerdos. Madrid: Afrodisio Aguado.

Cite this article

Mallen,E. (2023). Compositionality in Pablo Picasso’s Poetry. Advances in Humanities Research,3,1-20.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Humanities Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Apollinaire, G. (1918) “L’esprit noveau et les poétes”. Mércure de France 130.491 (December).

[2]. Baldassari, A. (2005) The Surrealist Picasso. New York: Random House.

[3]. Bernadac, M-L. (1989) “Le crayon qui parle.” Picasso poète. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux.

[4]. Bernadac, M-L. (1989) “La peinture à l’estomac: le thème de la nourriture dans les écrits de Picasso.” pp. 22–29. In: J. Sutherland, M-L. Bernadac & C. Piot (Eds.). Picasso. Écrits. Paris: Réunion des musees nationaux / Gallimard.

[5]. Bois, Y A. (1987) “Kahnweiler’s lesson.” Répresentations. 18. pp. 33–68.

[6]. Brassaï. (1969) Conversations avec Picasso. Paris : Gallimard.

[7]. Breton, A. (1988). Mad Love. New York: Bison Books.

[8]. Caparrós Esperante, L. (2019). “‘Dire le un’: Poesía y referencialidad en Pablo Picasso.” Anales de la Literatura Española Contemporanea. (January). 44.1 pp. 5-26.

[9]. Chomsky, N. (1995) The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

[10]. Cottington, D. (1998) Movements in Modern Art: Cubism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

[11]. Cowling, E. (2002) Picasso: Style and Meaning. New York, NY: Phaidon.

[12]. Culicover, P. (2016) “Parataxis and Simpler Syntax.” Ms. The Ohio State University and Eberhard-Karls Universität, Tübingen

[13]. Culicover, P. and R. Jackendoff (2005) Simpler Syntax. Oxford : Oxford University Press.

[14]. Deleuze, G. and C. Parnet. (1987) Dialogues. New York: Columbia University Press.

[15]. Ernst, Thomas. The Syntax of Adjuncts. (2004) Cambridge University Press.

[16]. Fernández Molina, A. (1988) Picasso, Escritor. Madrid: Prensa y Ediciones Iberoamericanas.

[17]. Fauconnier, G. (1985). Mental spaces: Aspects of meaning construction in natural language. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

[18]. Gilot, F. and C. Lake. 1964 Life with Picasso. New York: McGraw-Hill.

[19]. Gutiérrez-Rexach, J. (2012) “A linguistic approach to the poetry of Pablo Picasso”. pp. 89-104. In: N. Rißler-Pipka & G. Wild (eds.). Picasso – Poesie – Poetik / Picasso, his Poetry and Poetics. Aachen: Shaker Verlag.

[20]. Jackendoff, R. and E. Wittenberg (2014) “What You Can Say Without Syntax: A Hierarchy of Grammatical Complexity”. pp. 65–82. Frederick J. Newmeyer and Laurel B. Preston. (eds.) Measuring Grammatical Complexity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[21]. Joris, P. (2001) “The Nomadism of Picasso”. pp. 25–28. In: Jerome Rothenberg and Pierre Joris (Eds.). The Burial of the Count of Orgaz and Other Poems. Cambridge, MA: Exact Change Publishers.

[22]. Laporte, G. (1974) El amor secreto de Picasso. Barcelona: Euros.

[23]. Leiris, M. (2001) “Afterword.“ pp. 311-316. In J. Rothenberg and P. Joris (Eds.). The Burial of the Count of Orgaz and Other Poems. Cambridge, MA: Exact Change Publishers.

[24]. Mallen, E. (2923) Online Picasso Project (OPP). Retrieved from http:picasso.shsu.edu.

[25]. Mallen, E. (2018) “Parataxis and Interface Rules in Pablo Picasso’s Poetry." Interdisciplinary Journal for Germanic Linguistics & Semiotic Analysis. No. 23.1. pp. 73-111. Spring.

[26]. Mallen, E. (2015) “The Fichtean Anstoß and Pablo Picasso's Poetry.” Revista Académica liLETRAd, No. 1. pp. 251-261. Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla..

[27]. Mallen. (2012). “La poesía simpatética de Pablo Picasso.” pp. 105-140. In: N. Rißler-Pipka & G. Wild (eds.). Picasso – Poesie – Poetik / Picasso, his Poetry and Poetics. Aachen: Shaker Verlag.

[28]. Mallen, E. (2009). "The Multilineal Poetry of Pablo Picasso." Interdisciplinary Journal for Germanic Linguistics & Semiotic Analysis No. 14.2. pp. 163-202. Spring.

[29]. Michaël, A. (2015) “Picasso ou le plaisir de l’écriture et quelques résonances steiniennes.” Revoir Picasso. 28 mars, pp. 1-5.

[30]. Michaël, A. (2011) “Picasso poète: Une expérimentation permanente.” Études 9. (Tome 415), pp. 219-230.

[31]. Michaël, A. (2008) Picasso poète. Paris: Beux-arts de Paris.

[32]. Michaël, A. (2000) “Dans le laboratoire de l’ecriture de Picasso: presentation d’un dossier génétique.” Genesis. 15. pp. 11-28.

[33]. Parmelin, H. (2013) Picasso dit ... suivi de Picasso sur la place. París: Les Belles Lettres.

[34]. Potts, C. (2005) The Logic of Conventional Implicatures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[35]. Rißler-Pipka, N: (2015) Picassos schriftstellerisches Werk. Passagen zwischen Bild und Text, Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

[36]. Rothenberg, J. and P. Joris (Eds.). (2004) The Burial of the Count of Orgaz and Other Poems. Cambridge, MA: Exact Change Publishers.

[37]. Sabartés, J. (1953) Picasso: Retratos y recuerdos. Madrid: Afrodisio Aguado.