1 Introduction

The paper begins by describing the definition of discrimination and racial discrimination and the three levels of racism, as well as the harm that discrimination has caused black people at work, in life, and in health. Therefore, the discussion of this paper begins with the effects of racial discrimination, they have difficulty in getting promoted at work and even when looking for jobs, they have a much lower rate of return letters than whites because many of the leaders are white and they will favour people of their own race. In terms of medical care, white doctors often do not examine blacks properly or are too rough when dealing with them leading to more serious conditions for them. In addition the environment of the neighbourhood they live in is very bad, which is very unfavourable to their health. After that, the thesis specifically analyses the disadvantages and differences between them and the whites when it comes to work. The jobs of the blacks are less specialised and they are generally in lower level jobs. For example, in the nursing profession, even though the job is not technically difficult, there are significantly fewer blacks than whites in the leadership ranks. Some researchers have proposed that if the number of black leaders were increased, this would reduce the gap between black and white health. [12] In a comparison of promotion disparities between blacks and whites, blacks are harder to promote than whites. Education is an important determinant of promotion in a job that depends on it [13]. Finally, the paper elaborates on the contrast regarding job satisfaction. Most of the blacks have higher job satisfaction than whites. They are more appreciative if they receive support from their managers.

In conclusion, we find that the disadvantages of racial discrimination far outweigh its benefits. Therefore we need to reduce the negative effects of racial discrimination and call attention to the equality of rights between ethnic minorities and their other ethnic groups.

2 Research Review

2.1 Discrimination

2.1.1 What Is Discrimination

What is discrimination? When talking about discrimination, it primarily targets ethnic minorities and inflicts harm upon them, but of course there are examples of majority ethnic groups being discriminated against. There is a growing terminology that labels discrimination in a variety of ways, from racial discrimination, weight discrimination, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, disability discrimination and appearance discrimination. (Salentin et al., 2023) Among them, racial discrimination has attracted extensive attention and research from scholars. In the view of inherited physical and behavioral differences, race defines that human beings are divided into different groups: black, white, yellow, etc. Generally, racial discrimination means unequal treatment of individuals or groups of individuals due to race or ethnicity (Pager and Shepherd, 2008). At the end of 20th century, genetic studies argued the existence of races that are biogenetically distinct and refuted that racial discrimination was a cultural intervention, reflecting attitudes and beliefs to be determined (Peter et al., 2023). However, racial discrimination has evolved into racism over time. The argument that human beings can be divided into distinct and exclusive biological entities, which are called races, was argued by some researchers. A causal relationship exsited between inherited physical traits and intelligence, morality, personality and other behavioral and cultural traits. Some races are naturally superior to others. The term also applies to political, economic, or legal institutions and systems that engage in or perpetuate discrimination on the basis of race or otherwise exacerbate racial inequalities in wealth and income, education, health care, civil rights, and other areas. In the 1980s, academics have focussed on this institutional, structural, or systemic racism. However, since the late twentieth century, the concept of race based on biological entities has been challenged and questioned, and biological race has been considered a cultural invention with absolutely no scientific foundation (Smedley, 2023) .

2.1.2 The Effect of Discrimination on Different Groups

2.1.2.1 Race Discrimination

A culture of racial discrimination is prevalent among United States, with the same rate of discrimination today as in the 1980s (Payne, 2019). It is widely known that blacks are strongly discriminated against in the United States as a disadvantaged race. Specifically, the influences of racial discrimination on blacks related to jobs (interviews), housing, health, and education have received much attention and have been investigated in depth by several researchers. First, when it comes to jobs, African Americans are treated unfairly from the moment they apply for a job. The response rate for blacks is 50% lower than that of equally qualified whites, and they also raise the qualifications of applicants in a way that benefits whites and not blacks. This ultimately led to the response rate of those with higher skills widening the gap between societies, thus exemplifying the unfairness of racial discrimination. Even when blacks are hired, studies have shown that they are paid far less than whites. In addition, the unemployment rate for African Americans is double that of whites, which makes their situation in the United States even more torturous, causing many to be stuck with the lowest level jobs, such as, cab drivers and so on. This eventually leads to robberies, violence, and other horrible acts by blacks. Secondly, in terms of housing, there is still widespread discrimination in the housing and rental market. Many blacks live in fixed neighborhoods that are in a state of disrepair, largely because they don't have the money to maintain them and because whites don't allow them to live in their neighborhoods. And, moreover, studies have shown that home mortgages for blacks are more than 0.5% higher than for whites. Although there is only a 0.5% difference, the money blacks get for their jobs becomes harder to pay their loans because of discrimination. In the end a vicious cycle is created and very few people are trying to change this, although there are many studies that illustrate the consequences of racial discrimination. Thirdly, when it comes to health, doctors also treat African Americans very differently - not taking a closer look at their symptoms, leading to the possibility of further deterioration of their symptoms. In the just recently passed COVID-19 Epidemic, a study stated that the death rate for blacks was 2.3 times that of whites and Asians (S. Leitch et al., 2023). Finally, in education, direct evidence of this discrimination against minorities are exsisted in other areas as well. Emails from students of color are more likely to be ignored by professors.

2.1.2.2 Gender Discrimination

Gender discrimination is when some people are treated unequally and unfairly because of their gender identity. Like all discrimination, gender discrimination is a violation of human rights that manifests itself in gender-specific unequal treatment and violence. As with racial discrimination, women are subjected to similar unequal treatment in terms of wages, education and health care. First, when it comes to work. Men and women may have some differences in experience, ability and physiology, as well as some gender-based phenomena. For example, women are paid 20 cents less than men. And, many women are harassed and discriminated against in the workplace, and they often have to put up with it in order to have a stable job. Of course, nowadays, the society has realized the danger of such discrimination and has enacted laws to regulate it, which can help them to narrow the gender gap in economic and opportunity. There are countless discrimination in education. This is because the level of education largely determines people's future employment, which brings about adverse effects in terms of health, poverty, and knowledge. (Soken-Huberty) When some people receive a lower level of education than most, leaders will belittle you later in the job search process because of your education. And women are generally less educated than men, so it will show in employment. To take it a step further, black women are more underprivileged than others, and they are negatively affected by both racial and sexual discrimination.

2.1.2.3 Weight Discrimination

When it comes to weight, obese people are treated unfairly in their daily lives and health. Studies have shown that people tend to have negative stereotypes about people with higher body weights, leading to the phenomenon that people with high body weights are discriminated against in their daily lives, which also gives them bad experiences in their daily lives. As the saying goes, discrimination is a key factor affecting health, and weight discrimination in daily life can lead to a vicious cycle of continuous increase in the BMI of these otherwise high-weight people. First of all, high weight people are often perceived as lazy, incompetent and undisciplined figures, and their weight is perceived to be highly controllable, while those with higher weights are thought to be responsible for their weight. These stigmatizing statements about them lead to their social marginalization [9]. And in everyday life, people tend to compare these high weight people to thin people, which adds to the sting and powerlessness they feel inside. When both are shopping at the mall, the salesperson will prioritize the thin person and treat him/her more friendly and kind. And even sometimes they will simply ignore the feelings of the person with higher weight. And, whereas people who experience weight discrimination have been shown to be more susceptible to a number of mental illnesses and physical ailments such as depression, substance use, diabetes, and so on. These undoubtedly reduce the life expectancy of people with high body weight, which shows the seriousness of the consequences of discrimination. When a person goes to the same store or hospital before and after gaining weight the service they are received is completely different: the treatment or therapy you receive, the way those doctors treat you, the care they take, increases dramatically when you become thinner. [9]

2.2 Racism

2.2.1 What Is Racism

2.2.2 The History of Racism

Fundamentally, how did racism come about? James Jones states that there are three levels of racism which are linked together and can evolve into a theory.

2.2.2.1 Cultural Level

From the beginning of slavery in 1865, and the Black Codes establishing the subordination of blacks. Even though the system of black oppression, which lasted for almost 60 years, was abolished in 1964, discrimination against blacks has never stopped. How can we explain the intergenerational continuity of this phenomenon of racial discrimination, even though we have been trying to stop and eliminate it? The only explanation for this phenomenon is that the spread of racism is cultural, a particular set of values, attitudes, and beliefs [4].

2.2.2.2 Institutional Level

At the institutional level, essentially all public facilities are racially segregated (including movie theaters, schools, hospitals, places to work, residential areas), whites have better facilities, blacks are worst off, and blacks must respect whites. In contrast, racism in the North was indirect and covert While both the North and South had measures like segregation, the difference was that racism in the North was unguided and unspoken to lead the development of the ideology. Of course, both institutional expressions shared a common goal: to ensure the subordination of blacks. So racism can be altered in these ways: homes, jobs (when interviewing, hiring, working), healthcare, school integration, changing institutions [4].

2.2.2.3 Individual Level

Individual acts of racism make up the third level of racism (Shah, 2008). For most whites, racism is not innate, it is influenced by the environment, the outside world. Those who live and work with blacks are less inclined to be prejudiced and may even be opposed to racism (Williams, 1975). Those who are well-educated and well-informed are also less inclined to be prejudiced. Only a minority of whites are still forced to act racist, in places where racial prejudice is not the norm and racist behavior is not tolerated (Pettigrew, 1981). Most people are malleable to racism, it just depends on whether or not they have been taught [4].

2.3 The Effect of Racism on Black People in the Workplace

2.3.1 Hunting Job

Web-based job search plays an essential role in molding labor market outcomes. It it an informal search method that individuals use probably when looking for a job (e.g., family, friends, and acquaintances who provide information about job leads),. Web-based search may have an efffect on the way in which labor market outcomes are obtained by providing key resources and signals to job seekers. Also providing potential employers with information about worker quality (Castilla, Lan, and Rissing, 2013a). It estimates that through these informal searches, about half of employments are found, rather than formal job search methods like online or newspaper job postings (see Corcoran, Datcher, and Duncan, 1980)

Smith (2005) points out that individuals in low-income African American communities may be hard to make job transitions and to be uncertain about their employment security.

Two potential pathwayse have been conceptualize through which social networks may be involved in perpetuating racial disparities when looking for jobs. The first stressed racial differences in access to information and the resources that flow through social networks. The second focuses on cumulative use of networks. These pathways both point out how different employment opportunities blacks and whites may experience on the social networks. The network access pathway builds on the work of Wilson (1987, 1996), which stressed the segregation of African Americans, particularly low-income African Americans, from exposure to hiring Education in the formal labor market (Briggs 1998; Rankin&Quane, 2000). Research in this filed typically argues that African Americans use networks to a lesser extent (Marsden 1987) or have less connection to social networks, especially networks change who can help identify or promote employment opportunities (Kasinitz and Rosenberg, 1996; Tigges, Browne, and Green, 1998). Compare with White job seekers, there is less access to networking resources for Black job seekers during the job search process. It means that specific job openings from Web-based sources will be less likely to be known by Black. This is because Web-based searches are supposed to be positively connected with job opportunities. However, the extent of network segregation experienced by African Americans have been doubted some researchers (Newman, 1999; Oliver, 1988). In fact, existing empirical research suggests that compared with non-minorities, minority job seekers are tended to find and obtain jobs through informal, online channels (Elliott, 1999; Green, Tigges, and Diaz, 1999; McDonald, Lin, and Ao, 2009). Relatedly, McDonald (2011) suggests that African American workers receive a similar number of jobs as white males instead of minorities being cut off. In terms of social networks, this academic direction points out that not all networks are created equally ot the same (Smith, 2005, 2007).

2.3.2 Job Type

Hispanic workers are severely underrepresented in the STEM labor force - accounting for only 8 percent of STEM workers. However, they account for a higher percentage of other jobs, such as health-related jobs and computer jobs. Black workers account for 11 percent of total employment in all occupations and 9 percent of STEM workers. It remains the same since 2016. Black workers make up only 5 percent of total engineers and architects, and 7 percent of workers work for computer-related jobs. (STEM labor refers to work that relies on a broad definition of science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) workers. STEM work is defined only based on occupations and includes 74 standard occupations in the life sciences, physical and earth sciences, engineering and architecture, computer and mathematical occupations, and health-related occupations, healthcare providers and technicians.) The STEM job clusters in which blacks make up the same percentage of the total labor force are health-related STEM occupations. White workers make up two-thirds of the share of workers in STEM occupations, exceeding their share of workers in all occupations. Employment rates for whites in all STEM occupation groups have declined since 2016, reflecting a general decline in employment rates for whites. Native Americans, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and people who identify with two or more racial groups make up a very small portion of STEM workers. An analysis of occupational employment forecasts before the pandemic shows that STEM employment is expected to grow.

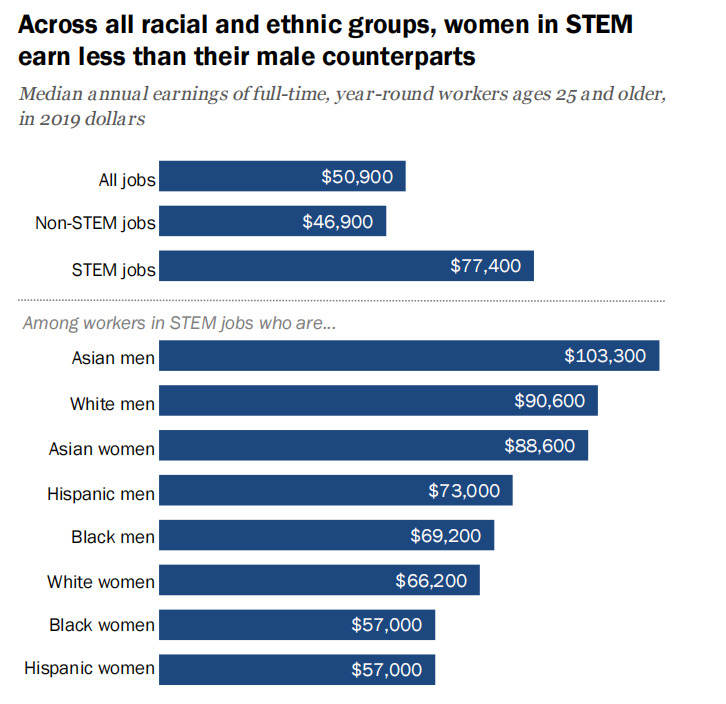

Figure 1. Across all racial and ethnic groups, women in STEM earn less than their male counterparts

Blacks are generally underpaid in the STEM workforce. In recent years, the earnings gap was 81 percent between blacks and whites in the STEM workforce. Hispanic workers in STEM earn about $65,000, or 83 percent of a typical job white does. In 2016, the pay gap was 85 percent between Hispanics and whites in the STEM workforce. White workers in STEM are more likely to be paid less than Asian workers. There is also a gender wage gap between workers of every race and ethnicity, resulting in the lowest earnings for black and Hispanic women in STEM jobs. This gap is the same for all workers. Numerous studies have suggested that the gender, racial, and ethnic group pay gap persists as education and job characteristics are controlled for.

Before the pandemic, the percentage of Hispanics entering college was increasing and more Hispanics were earning bachelor's degrees. Since the beginning of the outbreak, college enrollment among Hispanics has declined. There is skepticism that these increases will continue. Despite the increases since 2010, Hispanic adults are still less likely to realize the increases than Whites, Asians, and Blacks are underrepresented among STEM degree recipients (Funk et al., 2021)

In the United States, the total number of minority nurses has increased, however, the number of Black nurse leaders and faculty remains significantly low. In approximately 2017, there were 4 million registered nurses in the United States, 19.3% of whom identified themselves as minorities,. There is only 6.2% identified as Black or African American, which is less than half of their numbers in the U.S. The NLN Nursing Faculty 2017 Census of Registered Nurses survey revealed that only 8.8% of nursing faculty were African American, compared to 80.8% of Whites. Minority nurse leaders play an integral role in mentoring, advancing new knowledge, and fostering diverse perspectives among nurses and nursing students that will promote equity in a diverse global society. However, the data indicate a low number of leaders who are very focused on minority nurses, especially in higher-level and influential leadership positions. Furthermore, it is recommended that nursing should prioritize the development of racial or ethnic minority individuals to assume greater leadership roles as a means of reducing health disparities. The lack of Black nurses in leadership and academia has been cited as one of the reasons for the underachievement of minority students in nursing, career advancement, and the resulting persistent health disparities. The AACN recognizes the need to recruit more faculty from minority populations as a strategy to attract diverse nursing students. However, due to the lack of minority leaders and faculty, the administration has reduced this transfer of political and social capital. Diversity is known to be a valuable resource. In addition to helping students succeed in nursing education or new nurses adapt to new environments, good mentors from diverse racial backgrounds ensure that nurses from similar backgrounds understand them so that they are not looked down upon in the nursing profession and are capable of doing the job. According to the report, African American faculty experienced challenges related to racial discrimination; however, it also strengthened their commitment to stay in academia [12].

2.4 Job Promotion

The study investigated the reasons for the promotion gap between females and minorities relative to white males, and the extent to which the processes leading to promotion differed between these groups. White males' labor market prospects are enhanced by sponsored mobility processes. White males have more access than women and ethnic minorities to job networks that promote mentorship. Conversely, formal credentials are more scrutinized than for minorities and women. The racial and gender differences in promotion outcomes are largely a function of group differences in former and current labor market factors. As Kalleberg and Reskin [13] point out, education is an important determinant of a type of promotion in a job that relies on it. However, Blacks and Latinos have lower average levels of education than Whites, so this may be relevant in explaining differences in promotions between these groups. Additionally, when considering the intersection of race and gender, the study shows that white males have the highest level of education, with 14.3 years of education. This compares to 13.9 years for white females, 13.2 years for black males and black females, 10.5 years for Latino males, and 10.2 years for Latino females. In addition to education, such as work experience and years of experience, are said to be more closely related to promotions because they indicate a company's commitment to the employees they are working with (Smith, 2005).

2.5 Job Satisfaction

Findings suggest that non-Hispanic blacks and other races are more likely to be satisfied with their jobs than whites and non-immigrant workers, and that this association is moderated by NA-perceived supervisory support. Minority or immigrant LTCW may be more sensitive to supervisory support and more appreciative if they receive support from their supervisors. Managers should be aware of these racial differences, and by providing support, they can increase NA job satisfaction and reduce turnover.

Research has shown that job satisfaction is related to other important attitudinal and behavioral outcomes such as work effort (Testa, 2001), organizational citizenship behavior (Lowery, Beadles, and Krilowicz, 2002), job performance (Judge, Thoresen, Bono and Patton, 2001; Rich, Lepine and Crawford, 2010), organizational commitment (Chordiya, Sabharwal and Goodman, 2017; Lok and Crawford, 2001; Tett and Meyer, 1993) and turnover (Tett and Meyer, 1993; T. A. Wright and Bonett, 2007). By influencing these outcomes, job satisfaction can have a significant impact on organizational performance, not only in the private sector but also in governmental organizations (Kim, 2004).

Worker satisfaction is determined by the correspondence between an individual's needs and the reinforcement provided by the work environment. Low correspondence can lead to adjustment behavior or turnover intentions, which can affect job performance and tenure. Since employees' social and occupational values determine horizontal correspondence (Leong and Serafica, 1995), the cultural and occupational values and needs of the group of evidence for minority differences (Brown, 2002) can be easily translated into different responses to workplace characteristics and experiences.

3 Discussion / Development

After analyzing the origins of racism in the United States, we have gained a better understanding of racial discrimination, especially the job encounters of blacks. This section will further discuss the impact of racial discrimination on blacks' job search, job promotion and job satisfaction. Overall, racial disparities in the labor market exist at almost all stages of the employment work process and African Americans face disadvantages compared to whites. [21]

3.1 Job Search

The first step that job seekers face before entering the labor market is to look for a job, more precisely they need to know where to get job-job information. And where to get job information, also known as recruitment channels, is very important for job seekers to find a job. In the United States, racial disparities in the labor market remain large and persistent. The role of persistent racial discrimination in hiring has been well documented [2] [21], and barriers to entry into the workplace often emerge through less direct and more informal channels that can precede, replace, or influence formal hiring decisions. In other words, jobs are often filled without any formal recruitment process [27], and even when such a recruitment process exists, the influence of social connections remains strong [8]; Granovetter, 1973). This suggests that good job opportunities tend to spread through relationships, and when blacks do not have more friends, especially white friends, as discussed earlier whites are taught to stay away from blacks while growing up, so that blacks are not exposed to some job opportunities.

In cases where they learn of openings through network channels, Black job seekers are less likely than White job seekers to know someone at the company for which they are submitting an application, and have their networks mobilize key resources on their behalf, especially by contacting employers on their behalf. This-network placement and network mobilization-helps explain the difference between blacks and whites in the roughly one-fifth of job offers among applications through social network-based channels. This finding helps us understand why web-based searches are more unfavorable to black job seekers than white job seekers. [21]

However, when we review the job path of former U.S. President Barack Obama, it is not difficult to realize that personal competence is also important in job searching; Obama's learning experience, personal competence, was an enabler for his career in politics. When a lack of ability to job seekers, interpersonal relationships to bring him good job opportunities, and finally he inevitably missed the opportunity. However, if one cannot even get in touch with job opportunities, even if one has good working ability, one cannot find a good job that matches the job, which is the experience of most of the black people in the United States.

Indeed, in reflecting on the importance of social networks in shaping racial differences in the labor market, according to Loury (2001), the main feature of racial discrimination used to be marked differences in racial treatment. In contrast, contemporary forms of discrimination are more likely to be supported in subtle ways by informal networks of opportunity. On the face of it, the use of social networks may appear to be race-neutral, but patterns of social and economic segregation mean that their impact will always disadvantage members of historically marginalized groups (blacks).

Thus, blacks are at a disadvantage in job searching, especially in searching for information and in interpersonal relationships, compared to whites.

3.2 Job Promotion

In job promotions, the labor market prospects of white males are enhanced through the process of sponsored mobility. Compared to minorities, white males have greater access to work networks that fuel mentorship and promotion relationships with superior white males. According to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), white males held approximately 60 percent of officer and manager positions from 1998 through 2002. In contrast, minorities (including blacks) are seen as disadvantaged. In this context, promotion decisions are less likely to be influenced by patronage relationships, instead, formal minority qualifications are scrutinized more closely than those of their white male counterparts --- the process is known as competitive mobility. And, there is evidence that when competing for promotions [1], particularly for managerial positions [28][29] and managerial positions [18][24] when Blacks' human capital credentials are scrutinized more closely than Whites' credentials and are subject to more restrictions, making it more difficult for Blacks to advance to higher positions on the job.

However, the promotion gap between blacks and whites is virtually nonexistent, and there is no evidence that network sponsorship improves the chances of promotion for white males any more than it does for other groups (Ryan, 2005). As we have seen with the promotion of former U.S. President Barack Obama, the promotion gap between him and whites in the presidential race was nonexistent. If it is true that the promotion gap between blacks and whites is non-existent, then how can one explain the fact that blacks make up a very small percentage of the top management in politics and business? So, the case of Barack Obama is not universal, and how does one prove that Barack Obama has not been promoted in his job through network sponsorship meetings? So, blacks are at a disadvantage in career advancement compared to whites, and they have difficulty in advancing to higher positions.

3.3 Job Satisfaction

In the United States, blacks are mostly in the bottom jobs. Blacks are more commonly found than whites in jobs such as security guards, nursing, janitorial, sanitation workers, and babysitters. These jobs are low-paying, have poor benefits, and are difficult to promote. Evidence suggests that leaders' performance evaluations of subordinates largely influence employees' assessments of job satisfaction. In racially discriminatory cultures, those evaluating performance tend to give more favorable evaluations to people of the same race [15], and given that most managerial positions are held by Whites, minority employees tend to receive less favorable evaluations or perceive the evaluation process as less fair than that of their White colleagues. And, they may also believe that performance metrics are biased against them, focusing on attributes or competencies that favor Whites, and therefore evaluate people of color less favorably. Minority employees are less satisfied with their jobs if they are skeptical of performance evaluations and thus underestimate the importance or value of receiving positive feedback in the form of recognition for good work.

However, in addition to differences in the relative importance of some of the determinants of satisfaction, there were also significant differences in the absolute strength of some of these factors, such as payment, participation, and diversity management. For these three factors, race had a similar effect in distinguishing the job satisfaction responses of Whites and Blacks. In other words, in each of these three factors, the factor affected Blacks to a greater degree than Whites, indicating greater or lesser importance. For example, diversity management makes minorities more satisfied with their jobs (Hawes and Wang, 2022).

Therefore, blacks and other races and immigrant workers are more likely to be satisfied with their jobs compared to whites (Hawes and Wang, 2022). Despite the fact that working conditions and situations for blacks differ greatly from those of whites, and that in most fields blacks have difficulty getting promoted and work at the bottom of the ladder. Blacks are more likely to give high job satisfaction ratings.

4 Conclusion

The paper begins with an overview summarizing the definitions of discrimination, manifestations, racial discrimination and racism. The discussion centers on the discriminatory behaviors that blacks would encounter in their lives while in the United States. Racial discrimination is emphasized, while weight discrimination, and gender discrimination are also mentioned. Blacks are usually discriminated against in terms of work, living, education, and healthcare. The response rate to their resumes is much lower than that of whites, and because most of them are not as educated as whites in terms of education, the social gap between the two races is widened, and most of the blacks can only do the lowest level of work. In addition, the discrimination phenomenon has not been reduced too much, and the blacks are in a very difficult situation. In terms of living, the environment of the particular neighborhoods where blacks live is very poor and the environment is also very bad. Because of the poor living conditions and quality of life, blacks are more likely to get sick. And white doctors sometimes don't examine them responsibly, which leads to further aggravation of their condition. It is like a cycle, if racial discrimination is not alleviated or solved, it will be very difficult for blacks to improve their social status. Therefore, the purpose of this essay is to analyze the people and the scope of the phenomenon of racial discrimination to call for the awareness of the dangers of discrimination, and also want to remind the white people of the drawbacks of their move.

The second part of the article focuses on comparing the differences between blacks and whites in finding jobs, types of jobs, and job satisfaction in society. Upon sifting and analyzing the data, blacks generally submit their resumes to the bottom jobs (waitresses, security guards). These jobs are low paying and difficult to promote. So, the impact of the leader's evaluation will be a bit more important than the top jobs. But their leaders are basically white and tend to give more favorable evaluations to people of the same race so the evaluation process is less favorable to them. Thus, underestimating the abilities of blacks leads to a decrease in their satisfaction. And African Americans use the internet for social networking to a lesser extent, whereas statistically more than half of all jobs are found through informal searches like the internet. This suggests that it is more difficult for them to find a job because they rarely hear about a job opening from online sources. Compared to whites, blacks are generally underpaid. Studies have shown that the gender, racial, and ethnic group pay gaps persist as controls are made for education and job category. Blacks also make up a small percentage of leaders and academics in health care. Prioritizing the development of minorities for leadership could reduce health disparities.

For future research and development, such as what the public can do to reduce the existence of discrimination and what different social classes can do to mitigate the negative effects --- from the targets of discrimination to the responsibility of the society as a whole can be researched.

References

[1]. Baldi, S., & McBrier, D. B. (1997). Do the determinants of promotion differ for Blacks and Whites? Work and Occupations, 24(4), 478–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888497024004005

[2]. Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. American Economic Review, 94(4), 991–1013. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/0002828042002561

[3]. Bleich, S. N., Findling, M. G., Casey, L. S., Blendon, R. J., Benson, J. M., SteelFisher, G. K., Sayde, J. M., & Miller, C. (2019). Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of black Americans. Health Services Research, 54(S2), 1399–1408. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13220

[4]. Bowser, B. P. (2017). Racism: Origin and theory. Journal of Black Studies, 48(6), 572–590. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934717702135

[5]. Casey, L. S., Reisner, S. L., Findling, M. G., Blendon, R. J., Benson, J. M., Sayde, J. M., & Miller, C. (2019). Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer Americans. Health Services Research, 54(S2), 1454–1466. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13229

[6]. At, C. (1987). Affirmative action plan of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. University Of North Carolina At Chapel Hill.

[7]. Feagin, J. R. (1991). The continuing significance of race: Antiblack discrimination in public places. American Sociological Review, 56(1), 101. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095676

[8]. Fernandez, R. M., Castilla, E. J., & Moore, P. (2000). Social capital at work: Networks and employment at a phone center. American Journal of Sociology, 105(5), 1288–1356. https://doi.org/10.1086/210432

[9]. Gerend, M. A., Patel, S., Ott, N., Wetzel, K., Sutin, A. R., Terracciano, A., & Maner, J. K. (2021). A qualitative analysis of people’s experiences with weight-based discrimination. Psychology & Health, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2021.1921179

[10]. Greenhaus, J. H., Parasuraman, S., & Wormley, W. M. (1990). Effects of race on organizational experience, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 33(1), 64–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/256352

[11]. Hersch, J., & Viscusi, W. K. (1996). Gender differences in promotions and wages. Industrial Relations, 35(4), 461–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-232x.1996.tb00416.x

[12]. Iheduru-Anderson, K. (2020). Barriers to career advancement in the nursing profession: Perceptions of Black nurses in the United States. Nursing Forum, 55(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12483

[13]. Kalleberg, A. L., & Reskin, B. F. (1995). Gender differences in promotion in the United States and Norway. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 14, 237-264.

[14]. Kirkinis, K., Pieterse, A. L., Martin, C., Agiliga, A., & Brownell, A. (2018). Racism, racial discrimination, and trauma: A systematic review of the social science literature. Ethnicity & Health, 26(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2018.1514453

[15]. Kraiger, K., & Ford, J. K. (1985). A meta-analysis of ratee race effects in performance ratings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 70(1), 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.70.1.56

[16]. Lee, H.-W., Robertson, P. J., & Kim, K. (2019). Determinants of job satisfaction among U.S. federal employees: An investigation of racial and gender differences. Public Personnel Management, 49(3), 009102601986937. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091026019869371

[17]. Loury, G. C. (2001). Politics, race, and poverty research. In S. H. Danziger & R. H. Haveman (Eds.), Understanding poverty (pp. 447–452). Harvard University Press.

[18]. Mueller, C. W., Parcel, T. L., & Tanaka, K. (1989). Particularism in authority outcomes of black and white supervisors. Social Science Research, 18(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/0049-089x(89)90001-x

[19]. Norway. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 14, 237-264.

[20]. Health Promotion International. (2020). OUP accepted manuscript. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaa121

[21]. Pedulla, D. S., & Pager, D. (2019). Race and networks in the job search process. American Sociological Review, 84(6), 000312241988325. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419883255

[22]. Powell, G. N., & Butterfield, D. A. (1994). Investigating the ‘glass ceiling’ phenomenon: An empirical study of actual promotions to top management. Academy of Management Journal, 37(1), 68–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/256770

[23]. Rollins, J. (1985). Between women. Temple University Press.

[24]. Smith, R. A. (2001). Particularism in control over monetary resources at work. Work and Occupations, 28(4), 447–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888401028004004

[25]. Smith, R. A. (2005). Do the determinants of promotion differ for white men versus women and minorities? An exploration of intersectionalism through sponsored and contest mobility processes. American Behavioral Scientist, 48(9), 1157–1181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764205274814

[26]. Smith, R. A. (2005). Do the determinants of promotion differ for white men versus women and minorities? An exploration of intersectionalism through sponsored and contest mobility processes. American Behavioral Scientist, 48(9), 1157–1181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764205274814

[27]. Waldinger, R., & Lichter, M. I. (2003). How the other half works: Immigration and the social organization of labor. University Of California Press.

[28]. Wilson, G. (1997). Pathways to power: Racial differences in the determinants of job authority. Social Problems, 44(1), 38–54. https://doi.org/10.2307/3096872

[29]. Wilson, G., Sakura-Lemessy, I., & West, J. P. (1999). Reaching the top. Work and Occupations, 26(2), 165–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888499026002002

Cite this article

Chen,C. (2024). To What Extent Does Racial Discrimination Affect Blacks Working in the United States?. Advances in Social Behavior Research,10,16-24.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Social Behavior Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Baldi, S., & McBrier, D. B. (1997). Do the determinants of promotion differ for Blacks and Whites? Work and Occupations, 24(4), 478–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888497024004005

[2]. Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. American Economic Review, 94(4), 991–1013. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/0002828042002561

[3]. Bleich, S. N., Findling, M. G., Casey, L. S., Blendon, R. J., Benson, J. M., SteelFisher, G. K., Sayde, J. M., & Miller, C. (2019). Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of black Americans. Health Services Research, 54(S2), 1399–1408. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13220

[4]. Bowser, B. P. (2017). Racism: Origin and theory. Journal of Black Studies, 48(6), 572–590. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934717702135

[5]. Casey, L. S., Reisner, S. L., Findling, M. G., Blendon, R. J., Benson, J. M., Sayde, J. M., & Miller, C. (2019). Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer Americans. Health Services Research, 54(S2), 1454–1466. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13229

[6]. At, C. (1987). Affirmative action plan of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. University Of North Carolina At Chapel Hill.

[7]. Feagin, J. R. (1991). The continuing significance of race: Antiblack discrimination in public places. American Sociological Review, 56(1), 101. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095676

[8]. Fernandez, R. M., Castilla, E. J., & Moore, P. (2000). Social capital at work: Networks and employment at a phone center. American Journal of Sociology, 105(5), 1288–1356. https://doi.org/10.1086/210432

[9]. Gerend, M. A., Patel, S., Ott, N., Wetzel, K., Sutin, A. R., Terracciano, A., & Maner, J. K. (2021). A qualitative analysis of people’s experiences with weight-based discrimination. Psychology & Health, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2021.1921179

[10]. Greenhaus, J. H., Parasuraman, S., & Wormley, W. M. (1990). Effects of race on organizational experience, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 33(1), 64–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/256352

[11]. Hersch, J., & Viscusi, W. K. (1996). Gender differences in promotions and wages. Industrial Relations, 35(4), 461–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-232x.1996.tb00416.x

[12]. Iheduru-Anderson, K. (2020). Barriers to career advancement in the nursing profession: Perceptions of Black nurses in the United States. Nursing Forum, 55(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12483

[13]. Kalleberg, A. L., & Reskin, B. F. (1995). Gender differences in promotion in the United States and Norway. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 14, 237-264.

[14]. Kirkinis, K., Pieterse, A. L., Martin, C., Agiliga, A., & Brownell, A. (2018). Racism, racial discrimination, and trauma: A systematic review of the social science literature. Ethnicity & Health, 26(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2018.1514453

[15]. Kraiger, K., & Ford, J. K. (1985). A meta-analysis of ratee race effects in performance ratings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 70(1), 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.70.1.56

[16]. Lee, H.-W., Robertson, P. J., & Kim, K. (2019). Determinants of job satisfaction among U.S. federal employees: An investigation of racial and gender differences. Public Personnel Management, 49(3), 009102601986937. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091026019869371

[17]. Loury, G. C. (2001). Politics, race, and poverty research. In S. H. Danziger & R. H. Haveman (Eds.), Understanding poverty (pp. 447–452). Harvard University Press.

[18]. Mueller, C. W., Parcel, T. L., & Tanaka, K. (1989). Particularism in authority outcomes of black and white supervisors. Social Science Research, 18(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/0049-089x(89)90001-x

[19]. Norway. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 14, 237-264.

[20]. Health Promotion International. (2020). OUP accepted manuscript. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaa121

[21]. Pedulla, D. S., & Pager, D. (2019). Race and networks in the job search process. American Sociological Review, 84(6), 000312241988325. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419883255

[22]. Powell, G. N., & Butterfield, D. A. (1994). Investigating the ‘glass ceiling’ phenomenon: An empirical study of actual promotions to top management. Academy of Management Journal, 37(1), 68–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/256770

[23]. Rollins, J. (1985). Between women. Temple University Press.

[24]. Smith, R. A. (2001). Particularism in control over monetary resources at work. Work and Occupations, 28(4), 447–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888401028004004

[25]. Smith, R. A. (2005). Do the determinants of promotion differ for white men versus women and minorities? An exploration of intersectionalism through sponsored and contest mobility processes. American Behavioral Scientist, 48(9), 1157–1181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764205274814

[26]. Smith, R. A. (2005). Do the determinants of promotion differ for white men versus women and minorities? An exploration of intersectionalism through sponsored and contest mobility processes. American Behavioral Scientist, 48(9), 1157–1181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764205274814

[27]. Waldinger, R., & Lichter, M. I. (2003). How the other half works: Immigration and the social organization of labor. University Of California Press.

[28]. Wilson, G. (1997). Pathways to power: Racial differences in the determinants of job authority. Social Problems, 44(1), 38–54. https://doi.org/10.2307/3096872

[29]. Wilson, G., Sakura-Lemessy, I., & West, J. P. (1999). Reaching the top. Work and Occupations, 26(2), 165–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888499026002002