1 Introduction

After the Age of Discovery, Western European capitalist nations' merchants and adventurers pursued wealth to amass capital, resulting in intense materialism. From the mid-Ming Dynasty (mid-16th century) onwards, they arrived in the East like ants swarming to a host body, targeting Macau as a primary economic conquest, with ambitions to turn Macau into their colony. Leading this charge were the Portuguese, soon followed by other nations. This paper aims to examine the impact of colonial legal systems on the rights of indigenous people in Macau and how modern legal redress mechanisms address these historical injustices. Through historical record analysis, case studies, and quantitative data analysis, this paper seeks to reveal how the legacy of colonial law affects contemporary society and provides a reference for creating a fairer legal framework.

First, the abstract provides a concise overview of the research background and objectives; the literature review section then summarizes academic discussions on colonialism, noting the limitations of current research. The methodology section details the study design, including historical record and case analyses. The results and discussion section presents data analysis findings, evaluating the impact of colonial law on indigenous rights and the efficacy of modern legal redress mechanisms. Finally, the conclusion summarizes the findings and suggests directions for future research and policy improvements.

2 Related Works

Currently, numerous scholars study historical events related to colonialism. Amaro explores the role of the rooster as a cross-cultural object within the frameworks of postcolonial tourism and intercultural exchange, analyzing how its adaptability reflects complex interactions among power, identity, and culture, thus contributing to discussions on cultural symbols and collective identity in postcolonial societies [1]. Peralta examines the history related to (post-) migration and labor in the Portuguese Empire and its postcolonies, highlighting the racial homogenization processes woven by Western European (post-) imperial nation-states and the related phenomena of exclusion. To this day, these states have yet to recognize the full citizenship rights of the millions of racialized groups residing within European borders [2]. Xie et al. aim to analyze in detail the linguistic aspects (such as grammar, vocabulary, and etymology) of Portuguese and Chinese city names, as well as the emerging English names [3]. Mert notes that postcolonial feminism is a reflection on Western feminism, addressing issues faced by non-Western women [4]. Tomášek investigates the transformation process from imported foreign legal models into corresponding codified laws, referred to as "law in books," and, through specific cases, demonstrates how "law in action" gradually evolves in application, bringing laws originally of European origin closer to East Asian traditional thought [5]. Ayaz examines colonialism and its responses through Kamila Shamsie's In Every Stone There Is a God [6]. Kammen uses extensive colonial statistical data and combines it with polygamy taxation starting in 1923 to reconstruct the prevalence of polygamy from the late 19th century to 2022. Studies in Africa show that during the colonial period in Indonesia, the rate of polygamy decreased, only to rise again after gaining independence in 2002 [7].

Li A studied the commercial diplomacy between the United Kingdom and the People's Republic of China from the 1970s to the early 1980s, focusing particularly on British colonial rule in Hong Kong. He points out that although Hong Kong provided certain subsidies for British-made trains, its role as a "showcase" in Sino-British trade was not particularly significant [8]. Ricart-Huguet's research indicates that the uneven distribution of colonial investment in 16 British and French African colonies was closely related to geographic advantages and historical trade positions [9]. Based on the theoretical framework of “political distortion,” Canen explains phenomena such as patronage, changes in contract enforcement, and political affiliations, from the perspective of political motives affecting resource allocation. He proposes measures to curb political distortion, such as election fund reform, bureaucratic reforms, free trade agreements, and technology introduction [10]. Turner’s research reveals that the emerging far-right environmental theory of "ecological boundaries" leverages inherent colonial and racialist ideas, attempting to obscure the central role of the Northern Hemisphere economies in the ecological crisis while shifting responsibility onto immigrants from the Global South [11]. Bernards' study highlights that the boom in financial technology in Kenya has reproduced the colonial-era pattern of uneven development, being mainly concentrated in Nairobi and Mombasa with an imbalanced urban-rural distribution [12]. Hartwig analyzes a recent dataset on the water usage experiences of Indigenous communities in southeastern Australia. He considers the persistent injustices as a form of "hydrocolonialism," pointing out that Australia's water resource development has so far brought little economic benefit to Indigenous communities, who remain marginalized in decision-making processes [13]. Existing research, while offering in-depth discussions on the multifaceted impacts of colonialism, still encounters certain bottlenecks. On the one hand, many studies focus on specific cases or theoretical frameworks, lacking interdisciplinary comprehensive analysis that could fully reveal the complex impacts of colonialism on different regions and cultural groups. On the other hand, while some research addresses postcolonial feminism and social justice, it often falls short in its attention to the specific experiences and voices of non-Western women. Additionally, limitations in data and the partial understanding of historical events also restrict a comprehensive assessment of colonial legacies and the effectiveness of modern redress mechanisms.

3 Methods

3.1 Colonial Oppression

The colonial legal systems were often marked by strong racial discrimination and oppressive characteristics, leaving lasting impacts on indigenous land, resources, and cultural rights. Colonizers typically used legal means to seize indigenous lands and excluded indigenous people from the legal system or placed them in a position inferior to the colonizers. The following outlines the primary impacts of colonial legal systems on indigenous rights and an overview of modern legal redress mechanisms:

(1) Conflicts Between Colonial Legal Systems and Indigenous Rights

Double Standards in the Legal System: In Macau, Portugal implemented a colonial legal system alongside Chinese traditional law, but the system tended to favor Portuguese citizens or residents with a colonial background. For instance, in matters of land allocation and commercial licensing, indigenous residents were often placed at a disadvantage and subjected to Portuguese government regulations.

(2) Conflicts Between Culture and Customs: Chinese legal culture emphasizes family ethics and interpersonal harmony, whereas Portuguese law carries strong religious and familial inheritance concepts. This difference made it challenging for many traditional customs of Macau's indigenous people to gain recognition within the Portuguese legal framework. For example, in issues of marriage and inheritance, Portuguese law tended to judicially favor its national customs and religious beliefs, undermining traditional inheritance practices within indigenous families.

(3) Restrictions on Indigenous Economic Activities: Under Portuguese rule, Macau’s economy was primarily centered on port trade. However, Chinese indigenous people in Macau faced restrictions in trade and import/export activities, making it difficult for them to compete with Portuguese merchants. This not only resulted in economic inequality but also further impacted the social status and living conditions of the indigenous population.

3.2 Establishment of a New Tax System: Implementation of the Chinese Tithe

João Maria Ferreira do Amaral, one of the Portuguese colonial governors of Macau, served as governor from 1846 to 1849. Upon taking office, Amaral recognized that enforcing the free port policy would inevitably lead to a loss of substantial customs revenue for Macau. To compensate, he sought to establish a new tax system, broadening the range of taxpayers. This strategy not only directly benefited the Portuguese government in Macau by sustaining colonial governance but also effectively undermined Qing authority over Macau by imposing tax obligations on the Chinese residents, transforming Macau into a region under Portuguese administration. Specifically, the governor directed the Leal Senado (City Council) to design a new tax system that would include tax policies targeting Portuguese, foreigners, and Chinese residents in Macau. The approach combined Western tax structures with Macau's local social context and led to the formation of a taxation agency, the Junta do Lancamento da Decima e mais impostos annexos, which was tasked with implementing this new tax system.

3.3 The Coolie Trade

Since the Portuguese occupation of Macau, Portuguese human traffickers had engaged in the trade of "倭奴" (Japanese slaves) and Chinese children. In 1614, Zhang Minggang, the Qing Dynasty’s governor of Guangdong and Guangxi, codified and publicly posted the Maritime Prohibition Regulations, which explicitly banned the purchase of humans in its fifth article. However, after the end of the Second Opium War in 1860, Macau’s foreign trade declined sharply, and the notorious "coolie trade" emerged as a major pillar of Macau’s pseudo-prosperity. According to official statistics from Macau, the number of piggy houses (institutions engaged in human trafficking, with Chinese laborers derogatorily referred to as "piggies" by the colonizers) grew from 8-10 establishments in 1856 to 35-40 establishments by 1866. Between 1856 and 1873, approximately 182,500 coolies were trafficked from Macau to overseas locations.

In addition, after Macau’s separation from Goa and its elevation to the status of an independently governed Portuguese province, the local government sought ways to sustain provincial fiscal expenditures. Governor Guimaraes authorized horse racing, making it legal and imposing taxes on racetracks. In 1847, the Portuguese government in Macau declared gambling legal, invited casinos through open bidding, and collected taxes from them as a primary source of revenue. According to Zheng Guanying’s Words of Warning in Times of Prosperity, by the 1870s, the number of fantan gambling houses in Macau had reached approximately 200.

3.4 Era of High Autonomy: Advancing Diversified Legal Education

On December 20, 1999, Macau successfully returned to the motherland, marking the formal establishment of the Macau Special Administrative Region (SAR) and the comprehensive implementation of the “One Country, Two Systems” policy. This was a milestone in Macau’s legal development history and a new starting point for advancing diversified legal education. From the onset of the SAR’s establishment, the government has proactively promoted cultural and educational initiatives, taking a local yet globally oriented approach to legal education. In addition to supporting the Faculty of Law at the public University of Macau, the government also earnestly encouraged private universities to offer legal education programs. Besides retaining the original Portuguese-language law courses, there has been a concerted effort to expand Chinese-language and English-language law courses. The curriculum has grown beyond Portuguese-language bachelor’s and master’s degrees to include bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral programs in Chinese. In addition to local law courses, the SAR also emphasizes Mainland Chinese law courses and internationally focused English-language law programs. Beyond conventional higher education, institutions like the “Legal and Judicial Training Center” provide training-oriented education. Overall, the move toward diversification has become a prominent feature of legal education development since the establishment of the SAR.

3.5 Application and Development of Modern Legal Redress Mechanisms

Following Macau’s return to China in 1999, the Macau SAR gradually established a legal system with Chinese characteristics in accordance with the Basic Law, striving to address the injustices left over from the colonial era and protect the legitimate rights of local indigenous populations.

Restoration of Land and Property Rights: Through legislation, the Macau SAR ensures residents’ property rights. Indigenous residents can apply for land use rights and property restitution, alleviating the colonial-era injustices related to land ownership.

Cultural Protection and Safeguarding of Traditional Customs: The Macau SAR respects local traditional culture and supports indigenous customs through cultural protection laws. For example, Chinese festivals and traditional cultural activities are preserved and promoted, with legislation supporting the cultural development of local associations.

Economic Support Policies: The Macau government offers a series of economic support policies for indigenous residents and other locals to mitigate economic inequalities inherited from colonial history [14-15]. For instance, the SAR provides policy support for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and local handicrafts to restore and promote local economic development.

Furthermore, regarding marriage systems, Portuguese colonial laws once failed to recognize indigenous traditional marriage forms, leading to unjust treatment of some indigenous marriages. After the handover, Macau’s legal framework recognized and protected the legality of all marriages, promoting a legal redress mechanism for marriage equality. This mechanism illustrates the compensatory role of the modern legal system in addressing the injustices of colonial history, balancing respect for traditional culture with contemporary legal principles and contributing to the protection of indigenous rights.

4 Results and Discussion

4.1 Experiment Objectives

(1) To analyze the impact of colonial legal systems on the rights of Macau’s indigenous people, focusing particularly on the deprivation of land ownership, cultural identity, and judicial rights.

(2) To evaluate the role of modern legal redress mechanisms in restoring indigenous rights and promoting social equity, with a specific focus on the effectiveness of Macau SAR’s legal and policy measures.

4.2 Experimental Subjects

The study selects Macau’s indigenous people or their descendants and, through case studies, examines the status of these individuals' and groups' rights under colonial and modern legal redress mechanisms. The analysis particularly focuses on land ownership, cultural identity, and judicial rights.

4.3 Experimental Steps

4.3.1 Literature and Historical Record Analysis

Collect legal documents from colonial-era Macau, historical records from the period of Portuguese rule, government archives, and local legal records to obtain primary sources on the colonial law's impact on indigenous people. This includes regulations and policy documents on land distribution, judicial rights, economic restrictions, and cultural protection. Modern Macau SAR laws and regulations, particularly those related to property restitution, cultural protection, and judicial equality, are also compared and analyzed.

4.3.2 Case Study Analysis

Select cases involving significantly affected indigenous individuals (e.g., cases where land property rights were deprived or traditional cultural practices suppressed) and conduct in-depth analysis of these individuals' historical records and current rights status. The impact of colonial laws is quantified by analyzing the extent of rights recovery before and after the handover, revealing the effectiveness of modern legal redress measures and areas for improvement.

4.4 Data Analysis

(1) Qualitative Analysis: Analyze interview content, compiling indigenous perspectives on colonial impacts and legal redress, to uncover the long-term effects of laws on individual and group rights.

(2) Quantitative Analysis: Based on case data, compare the implementation effectiveness of various policies (e.g., property restitution and cultural protection legislation). Metrics such as beneficiary ratios and satisfaction levels are calculated, using descriptive statistics to evaluate both the impact of colonial laws on indigenous people and the progress of modern legal redress measures.

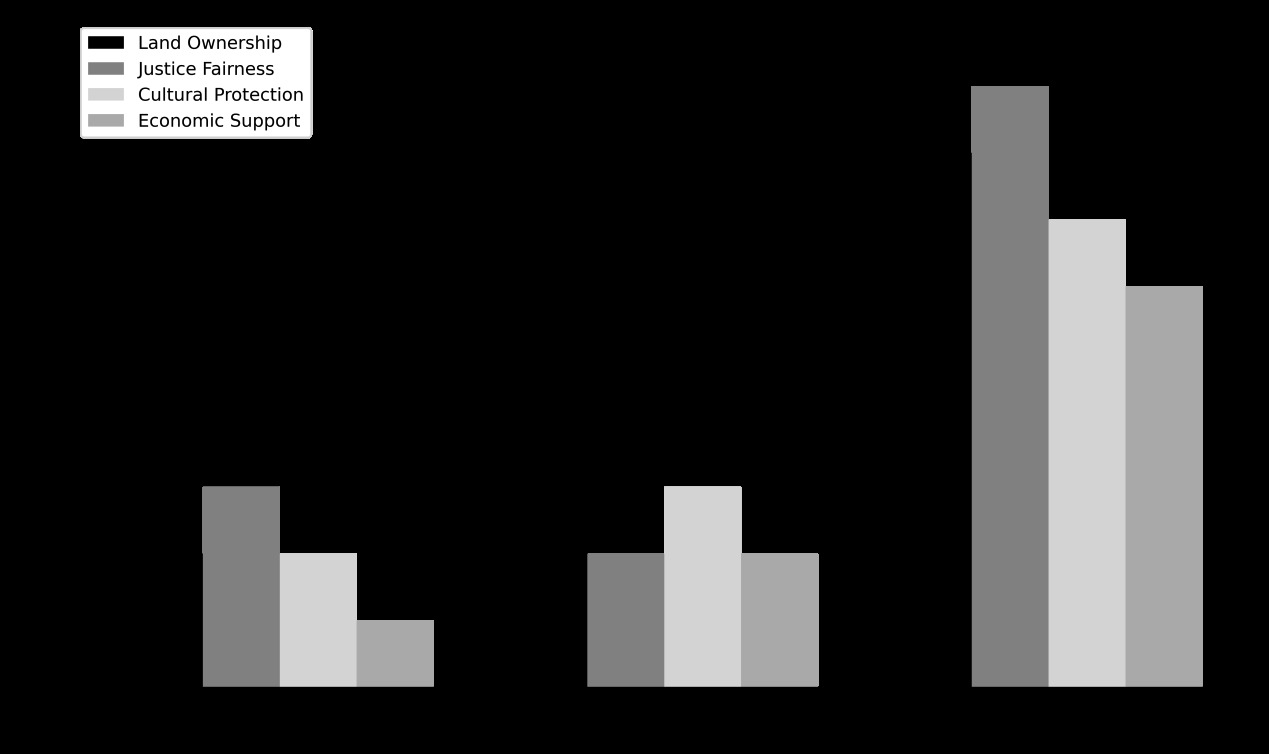

Figure 1. Changes in Indigenous Rights Across Different Historical Periods

The analysis of interview data reveals significant shifts in indigenous rights across historical periods. During the colonial era, indigenous land ownership was severely restricted, with a rating of 2 out of 10, reflecting systemic injustice and cultural marginalization. In the pre-handover period, rights improved, especially regarding judicial fairness, with a rating increase to 2, as shown in Figure 1.

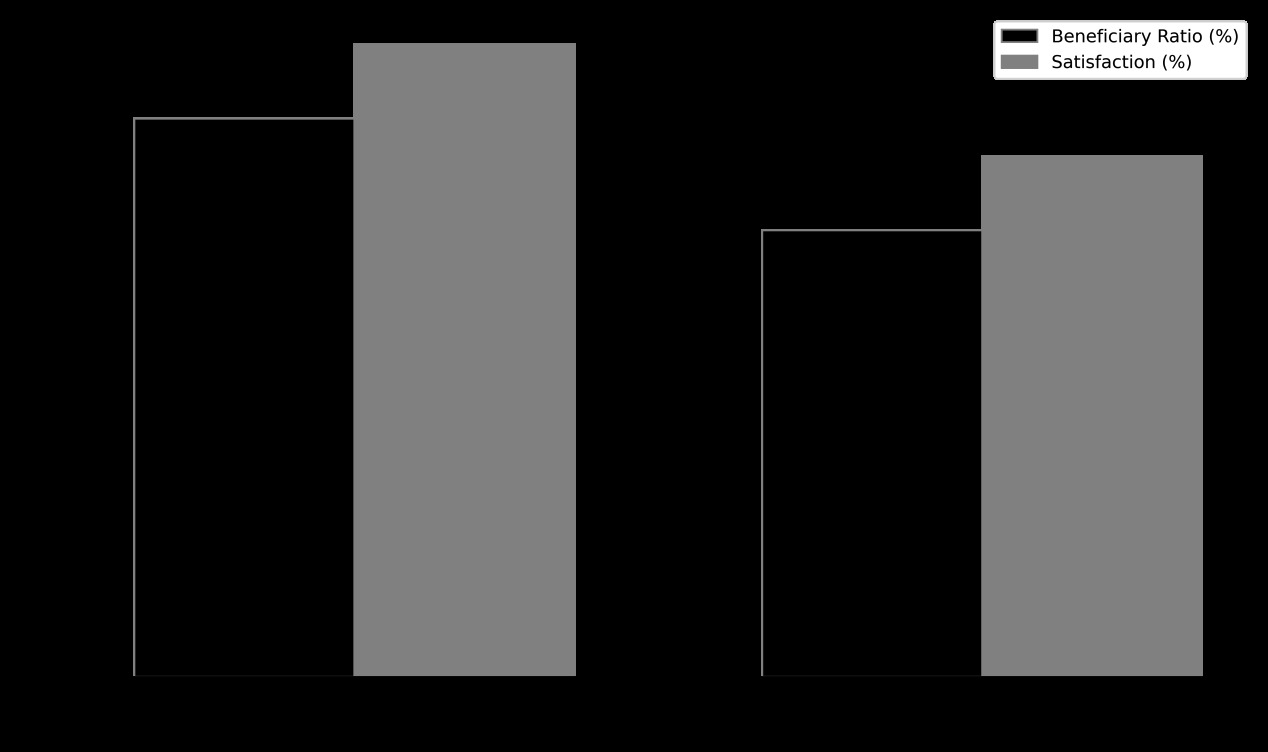

Figure 2. Impact of Policies on Indigenous Rights

Through quantitative analysis of survey and case data, we compared the changes in indigenous rights across different historical periods, focusing particularly on the implementation effectiveness of property restitution policies and cultural protection legislation. The results indicate that the beneficiary rates for these policies were 75% and 60%, respectively, while satisfaction levels reached 85% for property restitution and 70% for cultural protection. These data suggest that modern legal redress mechanisms have achieved some success in improving indigenous rights, with property restitution policies contributing more significantly to beneficiary satisfaction and rights protection than cultural protection legislation. This highlights both the lasting impact of colonial laws on indigenous rights and the positive role of modern legal frameworks in addressing these historical injustices, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 3. Impact of Colonial Laws on Indigenous Rights

Quantitative analysis of case data reveals a significant impact of colonial laws on indigenous rights, specifically in areas such as land dispossession (73%), loss of cultural practices (61%), judicial injustice (82%), economic disparity (68%), and social exclusion (62%). These data demonstrate the profound and negative effects of colonial laws on the fundamental rights of indigenous populations, particularly in judicial and land rights. Moreover, while modern legal redress mechanisms have made progress in alleviating these historical injustices, further research and evaluation are necessary to assess their effectiveness fully, as shown in Figure 3.

Table 1. Progress of Restoration in the Macau SAR After the Handover

Category |

Progress (%) |

Areas for Improvement (%) |

Land Rights Restoration |

82 |

18 |

Cultural Protection Satisfaction |

78 |

22 |

Marriage Equality Recognition |

87 |

13 |

Economic Support Coverage |

60 |

40 |

From the data in Table 1, it is evident that the success rate of land rights restoration has reached 82%, indicating positive outcomes from government efforts in this area. However, 18% of indigenous people still face challenges in securing land rights, highlighting the need for additional policy support. Further improvements in these areas are essential to achieve more comprehensive social equity and the full restoration of indigenous rights.

5 Conclusion

This study conducted an in-depth exploration of the impact of colonial legal systems on indigenous rights and examined the effectiveness of modern legal redress mechanisms in rectifying these historical injustices. The research indicates that Portuguese colonial laws resulted in significant inequalities for Macau’s indigenous population, particularly in areas of land distribution, cultural identity, and judicial rights, leading to structural exclusion within society. Since the 1999 handover, the Macau SAR has made notable progress in restoring indigenous rights, preserving cultural heritage, and promoting social equity through legislation and policy measures. Data analysis shows that the implementation of land rights restoration and cultural protection policies has significantly improved the rights situation of indigenous people, enhancing their satisfaction. However, certain areas still require further improvement, especially in extending economic support and the reach of cultural protection. Future research should continue to assess the effectiveness of legal redress mechanisms to ensure the full restoration of indigenous rights and uphold social justice and equity.

References

[1]. Amaro, V. (2024). Crowing in two voices: The cultural transformation of the Portuguese rooster in postcolonial Macau. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1-14.

[2]. Peralta, E., Delaunay, M., & Góis, B. (2022). Portuguese (post-) imperial migrations: Race, citizenship, and labour. Journal of Migration History, 8(3), 404-431.

[3]. Xie, Q., Ursini, F. A., & Samo, G. (2023). Urbanonyms in Macao. Names, 71(1), 29-43.

[4]. Mert, M. K. (2024). Looking at post-colonial feminism: A reading through the views of Maria Mies. Anadolu Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 24(2), 583-596.

[5]. Tomášek, M. (2023). Legal cultures between Europe and the Far East in historical context. Cesky Casopis Historicky, 121(2), 441-480.

[6]. Ayaz, S., Khan, S. S., & Ahmed, Q. H. (2023). Analyzing Kamila Shamsie’s A God in Every Stone: Colonialism and resistance. Pakistan Journal of Social Research, 5(1), 248-253.

[7]. Kammen, D., & Tian, Y. (2023). Polygamy in Timor-Leste: From colonial taxation to post-independence revival. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land-en Volkenkunde/Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia, 179(3-4), 353-381.

[8]. Li, A. M. Y. (2023). Hindrance or helping hand?: Hong Kong and Sino-British railway commercial diplomacy, 1974–84. The International History Review, 45(3), 590-605.

[9]. Ricart-Huguet, J. (2022). The origins of colonial investments in former British and French Africa. British Journal of Political Science, 52(2), 736-757.

[10]. Canen, N., & Wantchekon, L. (2022). Political distortions, state capture, and economic development in Africa. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 36(1), 101-124.

[11]. Turner, J., & Bailey, D. (2022). ‘Ecobordering’: Casting immigration control as environmental protection. Environmental Politics, 31(1), 110-131.

[12]. Bernards, N. (2022). Colonial financial infrastructures and Kenya’s uneven fintech boom. Antipode, 54(3), 708-728.

[13]. Hartwig, L. D., Jackson, S., Markham, F., et al. (2022). Water colonialism and Indigenous water justice in south-eastern Australia. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 38(1), 30-63.

[14]. Ayyash, M. (2024). Colonial racial capitalism and violence: Theorising the relationship between empire and Israeli settler colonialism. Journal of Holy Land and Palestine Studies, 23(2), 205-220.

[15]. Sondarjee, M., & Andrews, N. (2022). Decolonizing international relations and development studies: What’s in a buzzword? International Journal, 77(4), 551-571.

Cite this article

Huang,H.;Jin,Y. (2024). The Impact of Colonial Legal Systems on Indigenous Rights and Modern Legal Redress Mechanisms. Advances in Social Behavior Research,13,19-24.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Social Behavior Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Amaro, V. (2024). Crowing in two voices: The cultural transformation of the Portuguese rooster in postcolonial Macau. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1-14.

[2]. Peralta, E., Delaunay, M., & Góis, B. (2022). Portuguese (post-) imperial migrations: Race, citizenship, and labour. Journal of Migration History, 8(3), 404-431.

[3]. Xie, Q., Ursini, F. A., & Samo, G. (2023). Urbanonyms in Macao. Names, 71(1), 29-43.

[4]. Mert, M. K. (2024). Looking at post-colonial feminism: A reading through the views of Maria Mies. Anadolu Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 24(2), 583-596.

[5]. Tomášek, M. (2023). Legal cultures between Europe and the Far East in historical context. Cesky Casopis Historicky, 121(2), 441-480.

[6]. Ayaz, S., Khan, S. S., & Ahmed, Q. H. (2023). Analyzing Kamila Shamsie’s A God in Every Stone: Colonialism and resistance. Pakistan Journal of Social Research, 5(1), 248-253.

[7]. Kammen, D., & Tian, Y. (2023). Polygamy in Timor-Leste: From colonial taxation to post-independence revival. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land-en Volkenkunde/Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia, 179(3-4), 353-381.

[8]. Li, A. M. Y. (2023). Hindrance or helping hand?: Hong Kong and Sino-British railway commercial diplomacy, 1974–84. The International History Review, 45(3), 590-605.

[9]. Ricart-Huguet, J. (2022). The origins of colonial investments in former British and French Africa. British Journal of Political Science, 52(2), 736-757.

[10]. Canen, N., & Wantchekon, L. (2022). Political distortions, state capture, and economic development in Africa. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 36(1), 101-124.

[11]. Turner, J., & Bailey, D. (2022). ‘Ecobordering’: Casting immigration control as environmental protection. Environmental Politics, 31(1), 110-131.

[12]. Bernards, N. (2022). Colonial financial infrastructures and Kenya’s uneven fintech boom. Antipode, 54(3), 708-728.

[13]. Hartwig, L. D., Jackson, S., Markham, F., et al. (2022). Water colonialism and Indigenous water justice in south-eastern Australia. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 38(1), 30-63.

[14]. Ayyash, M. (2024). Colonial racial capitalism and violence: Theorising the relationship between empire and Israeli settler colonialism. Journal of Holy Land and Palestine Studies, 23(2), 205-220.

[15]. Sondarjee, M., & Andrews, N. (2022). Decolonizing international relations and development studies: What’s in a buzzword? International Journal, 77(4), 551-571.