1. Introduction

Tourism as a global economy is extremely vulnerable to crises, from natural catastrophes and disease epidemics to political instability and infrastructure breakdowns. The media, which can act as both a catalyst for crisis and a catalyst for healing, is critical in these moments. During emergencies, tourists seek out information in the news, via broadcasts, or social media, all of which directly affect their choices of travel. The depressing media coverage that emphasises loss, perpetual danger and instability drives away tourists, which leads to continued visitor declines. By contrast, neutral or positive media coverage that highlights rehabilitation, safety measures and local resilience can reinvigorate trust and drive visitors back. It’s vital that stakeholders – such as tourism boards, governments and businesses—are aware of the ways in which media coverage affects tourism recovery. How quickly and efficiently tourism recovers depends both on the crisis and on the message. Real-time, accurate information and stories that do the job of overcoming the stigma are key aspects of effective crisis communications. Thanks to the burgeoning role of social media, young travelers are particularly open to stories about healing and overcoming. The purpose of this paper is to explore how media coverage influences tourism recovery during a crisis. It employs both content analysis and surveys to analyze the impact of media narratives on tourist spending, recovery times, and industry resiliency [1]. Through the case studies of major crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, the Australian bushfires and the blockage of the Suez Canal, this study highlights practical methods that tourism stakeholders can use to reach out to the media and help accelerate recovery.

2. Literature review

2.1. Media impact on tourism crisis response

Tourism is a industry in which crisis management is closely linked to the role of the media as an information relay channel. Press power can play a pivotal role in reducing or exaggerating the detrimental impacts of a crisis on tourism. Ample sensationalist or hysterical media coverage of disasters, be they natural disasters, pandemics or political upheavals, can heighten anxiety and jitters among tourists. This oversimplified fear often discourages visitors from visiting the affected areas, leading to years of tourism revenue loss and poverty. These kinds of negative portrayals focus on the scale of destruction, continuous danger and ugliness and can reinforce beliefs about the destination as dangerous or unstable. In contrast, timely media reporting of reconstruction, the deployment of protections, and the good news contributes significantly to rebuilding public trust. Storylines that emphasise recovery, hope and progress assure visitors and motivate them to come back, enabling the flow of tourists to recover more quickly. For instance, images of healthy communities, reconstructed infrastructure, and reviews from returning travelers can create a positive image [2]. It is only temporary when a crisis feels fragile, and media accounts that emphasise its inability to be overcome reduce public fear and foster trust. Media (particularly big media) are therefore a key player in determining the direction and timing of tourism recovery. The media can derail or aid recovery in tourism by policing the tone and focus of reports, thus making it crucial to crisis management models.

2.2. Effect of media context on public attitudes

How the media portrays a tourism crisis has broad implications for how people will think about it, and what they’ll decide to do when travelling. Media framing—the construction and contextualisation of an event—shapes how viewers perceive and react to a fact. When a tourism disaster occurs, such as an earthquake, a pandemic or an accident, the scale of the crisis is often based on media framing. Reports about the severity, devastation and danger of a crisis can create fear, worry and dread in passengers. Such framing serves to reinforce the idea that a destination is risky or that dangers remain, thus disincentivising travel and slowing economic recovery. Conversely, news reports highlighting recovery, resilience and protection might shift narratives in positive ways. When reports focus on things such as effective emergency response, a community resilience or recovery, they give people security and optimism. For instance, narratives involving reclaimed areas, tourist reports or reopened sites create hope and encourage visitors to visit those places that had suffered [3]. Particularly on social media, attitudes are increasingly formed via real-time updates and comments, which reflect local, bottom-up realities. In contrast to traditional news outlets, social media gives room for less formal, anonymous stories that can complement or overpower the mainstream media narrative. Finally, the media’s power to construct a narrative, of devastation or healing, has a direct impact on the emotional state, risk-assessment and decision-making of visitors. An event described as disastrous can make us fearful indefinitely, while tales about strength, recovery and security foster confidence. These stories, therefore, not only inform but shape public opinion and tourism demand, and can have a huge impact on the rate at which destinations can recover their popularity [4].

2.3. Tourism sector responds to press reactions

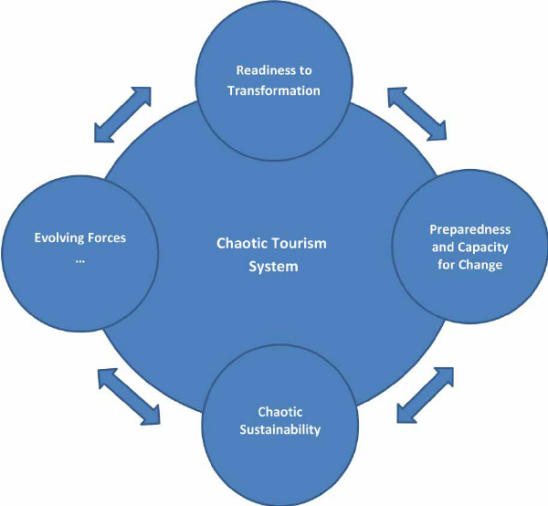

How the tourism sector reacts to media coverage during crises plays a critical role in how quickly and effectively recovery takes place. Tourism boards, governments and local entities need to engage actively with the media in order to have relevant, helpful, and current information available to the public. Communication tactics should include alerting the public to safety protocols, recovery activities, and restoration of the most important attractions to regain public trust. As shown in Figure 1, a disordered tourism system needs overlapping considerations of readiness for change, readiness and capacity for change, changing forces and disordered sustainability to manage disruptions. This connected model stresses flexibility and resilience in times of need. A coordinated effort among the media and tourism industry can offset the negative effects of a crisis by regulating the perception and encouraging positive stories [5]. When the media communicates grit, recovery outcomes, and industry readiness for transformation, visitors are willing to trust. In contrast, an inability to counter media narratives can increase uncertainty, further prolonging the healing process. Active media engagement, coupled with clear news and recovery timelines, reclaims the confidence of tourists and resuscitates local economies through prompt visits.

Figure 1. Tourism crisis management as a chaotic process (source: ResearchGate.com)

3. Methodology

3.1. Research design

The research combines qualitative content analysis with quantitative surveys in a mixed methodology. Content analysis analyzes media reports of tourism disasters for narrative structure; the questionnaire gathers quantitative data on how tourists see and act in light of such media reports. The crises in this paper range from the COVID-19 pandemic to the 2019-2020 Australian bushfires and the 2021 Suez Canal blockade. Table 1 shows what media sources were analysed—news, broadcast, and social media. Multimediality ensures that crisis stories are represented in a wide range of media, providing an inclusive lens through which to reflect [6].

Table 1. Types of media sources for content analysis

Source Type | Examples | Number of Entries |

International News Media | BBC, CNN, The Guardian | 250 |

Local News Outlets | Sydney Morning Herald, China Daily | 150 |

Social Media Platforms | Twitter, Instagram | 100 |

3.2. Sampling and data collection

The content analysis sample consists of 500 media reports published within 6 months of the identified tourism catastrophes. Posts were carefully chosen from global and regional media outlets, to offer both global and local insights. Social media information was pulled from Twitter and Instagram based on hashtags and posts regarding recovery efforts and safety. In the survey portion, 1,000 respondents were chosen from primary source markets for tourism—the US, the UK, Australia and China. Participants were questioned about safety, travel readiness and reactions to the media coverage of tourism disasters [7]. Table 2 provides a demographic profile of the respondents to the survey. These demographics reveal a healthy mix of age groups and local origins, making global tourism behaviour very easy to comprehend [8].

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of survey respondents

Category | Percentage (%) |

Gender: Male | 48 |

Gender: Female | 52 |

Age Group: 18-30 | 35 |

Age Group: 31-45 | 40 |

Age Group: 46+ | 25 |

Key Markets: US | 30 |

Key Markets: UK | 25 |

Key Markets: Australia | 20 |

Key Markets: China | 25 |

3.3. Data analysis

For qualitative content analysis, we coded using media framing and crisis communication models. News stories and blog posts were coded with messages of crisis intensity, recovery stories and emotional appeals. The review provided a way to see common trends in media coverage and how it could affect public opinion. For the survey data, descriptive statistics were used to quantify response rates and regression analyses examined relationships between types of media coverage and tourists’ decision-making [9]. Both analyses reveal how media messages impact tourist actions, safety and recovery rates. The combination of content analysis and quantitative surveys ensures a precise understanding of the role of media coverage in the tourism industry’s recovery.

4. Results

4.1. Media reporting and recovery trends

Our content analysis revealed that negative and positive media coverage affected tourism recovery very differently. Destinations whose media narratives—mostly grim and focusing on long-term damage, risk and uncertainty—took longer to recover. In the case of the 2020 Australian bushfires, for instance, attention to destruction meant visitor numbers declined by 40% in the first six months, and healing took much longer than expected. Instead, places with even-keeled or encouraging histories, like Japan after the 2011 earthquake, recovered faster – tourism visits returned to pre-crisis levels in just 12 months [10]. Table 3 summarizes recovery times for various crises, showing the relationship between media representation and recovery velocity. This is also evident in the data, which suggests that media interpretation directly impacts the time and strength of tourism recovery: negative news stories speed up recovery, while neutral news promotes faster recovery [11].

Table 3. Recovery timelines based on media coverage

Crisis | Media Coverage Type | Tourism Decline (%) | Recovery Period |

2020 Australian Bushfires | Predominantly Negative | 40 | 12-18 months |

2011 Japan Earthquake | Balanced/Positive | 30 | 8-12 months |

2021 Suez Canal Blockage | Neutral | 15 | 6 months |

4.2. Public perception and traveler behavior

The survey revealed that news reports influenced tourists’ travel choices. A large 72% of respondents reported that poor news coverage kept them from visiting places following a disaster. But if recovery efforts were stressed, 68% of participants indicated more willingness to rethink trips, which points to the possibility that positive media can help offset negative narratives from the past. Table 4 illustrates survey findings by age group and their response to news stories. These results demonstrate that young travellers pay close attention to media representations, especially those circulated via social media [12]. The younger they were, the more likely they were to be subjected to positive recovery messages—evidence of the need for specialised messages to rekindle confidence.

Table 4. Survey responses on media influence and travel behavior

Age Group | Discouraged by Negative Coverage (%) | Encouraged by Recovery Stories (%) |

18-30 | 78 | 74 |

31-45 | 70 | 65 |

46+ | 65 | 60 |

4.3. Industry response and crisis management

Places that actively engaged with media during crises recovered much faster. Proactive messaging—including highlighting safety procedures, recovery progress, and testimonials—lead to a 25-30% rise in bookings within three months. Destinations that were unable to manage their media campaigns instead saw ongoing declines in tourism. This result bolsters the argument that disclosure and media outreach are essential for reducing long-term impacts. Further, cooperation between tourism agencies, businesses and the media helped to curb crisis communications and reassure visitors. Tables 3 and 4 demonstrate the need to balance media coverage and public perception to drive recovery. Such findings show the important role that media attention and targeted communication can play in restoring post-event tourism demand.

5. Conclusion

This research highlights how important media coverage is in determining the course of tourism recovery after a crisis. The comparison shows that media reports’ tone and framing, whether negative, neutral or positive, had an enormous effect on public perception and travel decisions. Bad portrayals, which focus on dangers and persistent disruption, delay recovery times, such as the Australian bushfires of 2020. On the other hand, neutral, positive stories, such as those after Japan’s earthquake, build confidence and accelerate healing through their depictions of resilience, safety and healing. Survey results also highlight age-specific communication, with younger travellers being particularly influenced by recovery-related content, particularly social media. This underscores the imperative for tourism industry stakeholders to focus media coverage on varying audiences and underscoring positive outcomes. The study finds that media engagement, complemented by open communications and coordinated messages, are critical to reducing the negative impact of crises on tourism. Tourism boards, governments and companies can regain public trust and stimulate recovery by taking charge of narratives and building resilience. Future research could focus on the role of digital influencers and new technologies in shaping post-crisis tourism narratives, improving the sector’s resilience to disruption.

References

[1]. Wut, T. M., Xu, J. B., & Wong, S. M. (2021). Crisis management research (1985–2020) in the hospitality and tourism industry: A review and research agenda. Tourism Management, 85, 104307.

[2]. Ritchie, B. W., & Jiang, Y. (2021). Risk, crisis and disaster management in hospitality and tourism: a comparative review. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(10), 3465-3493.

[3]. Berbekova, A., Uysal, M., & Assaf, A. G. (2021). A thematic analysis of crisis management in tourism: A theoretical perspective. Tourism Management, 86, 104342.

[4]. Jurdana, D. S., Frleta, D. S., & Agbaba, R. (2020). Crisis management in tourism–literature review. Economic and Social Development: Book of Proceedings, 473-482.

[5]. Ertaş, M., Sel, Z. G., Kırlar-Can, B., & Tütüncü, Ö. (2021). Effects of crisis on crisis management practices: a case from Turkish tourism enterprises. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(9), 1490-1507.

[6]. Liu-Lastres, B. (2022). Beyond simple messaging: a review of crisis communication research in hospitality and tourism. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(5), 1959-1983.

[7]. Thirumaran, K., Mohammadi, Z., Pourabedin, Z., Azzali, S., & Sim, K. (2021). COVID-19 in Singapore and New Zealand: Newspaper portrayal, crisis management. Tourism Management Perspectives, 38, 100812.

[8]. Aldao, C., Blasco, D., Poch Espallargas, M., & Palou Rubio, S. (2021). Modelling the crisis management and impacts of 21st century disruptive events in tourism: the case of the COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism Review, 76(4), 929-941.

[9]. Avraham, E. (2021). Combating tourism crisis following terror attacks: Image repair strategies for European destinations since 2014. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(8), 1079-1092.

[10]. Kukanja, M., Planinc, T., & Sikošek, M. (2020). Crisis management practices in tourism SMEs during the Covid-19 pandemic. Organizacija, 53(4), 346-361.

[11]. Beirman, D. (2020). Restoring tourism destinations in crisis: A strategic marketing approach. Routledge.

[12]. Broshi-Chen, O., & Mansfeld, Y. (2021). A wasted invitation to innovate? Creativity and innovation in tourism crisis management: A QC&IM approach. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 46, 272-283.

Cite this article

Yuan,F. (2025). Tourism journalism in the age of crisis: how media coverage of tourism disasters affects industry recovery. Advances in Social Behavior Research,16(1),1-5.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Social Behavior Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Wut, T. M., Xu, J. B., & Wong, S. M. (2021). Crisis management research (1985–2020) in the hospitality and tourism industry: A review and research agenda. Tourism Management, 85, 104307.

[2]. Ritchie, B. W., & Jiang, Y. (2021). Risk, crisis and disaster management in hospitality and tourism: a comparative review. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(10), 3465-3493.

[3]. Berbekova, A., Uysal, M., & Assaf, A. G. (2021). A thematic analysis of crisis management in tourism: A theoretical perspective. Tourism Management, 86, 104342.

[4]. Jurdana, D. S., Frleta, D. S., & Agbaba, R. (2020). Crisis management in tourism–literature review. Economic and Social Development: Book of Proceedings, 473-482.

[5]. Ertaş, M., Sel, Z. G., Kırlar-Can, B., & Tütüncü, Ö. (2021). Effects of crisis on crisis management practices: a case from Turkish tourism enterprises. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(9), 1490-1507.

[6]. Liu-Lastres, B. (2022). Beyond simple messaging: a review of crisis communication research in hospitality and tourism. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(5), 1959-1983.

[7]. Thirumaran, K., Mohammadi, Z., Pourabedin, Z., Azzali, S., & Sim, K. (2021). COVID-19 in Singapore and New Zealand: Newspaper portrayal, crisis management. Tourism Management Perspectives, 38, 100812.

[8]. Aldao, C., Blasco, D., Poch Espallargas, M., & Palou Rubio, S. (2021). Modelling the crisis management and impacts of 21st century disruptive events in tourism: the case of the COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism Review, 76(4), 929-941.

[9]. Avraham, E. (2021). Combating tourism crisis following terror attacks: Image repair strategies for European destinations since 2014. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(8), 1079-1092.

[10]. Kukanja, M., Planinc, T., & Sikošek, M. (2020). Crisis management practices in tourism SMEs during the Covid-19 pandemic. Organizacija, 53(4), 346-361.

[11]. Beirman, D. (2020). Restoring tourism destinations in crisis: A strategic marketing approach. Routledge.

[12]. Broshi-Chen, O., & Mansfeld, Y. (2021). A wasted invitation to innovate? Creativity and innovation in tourism crisis management: A QC&IM approach. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 46, 272-283.