1. Introduction

Since the birth of Victoria's Secret Angel, their media image of "angelic face, devilish body" [1] has quickly become a model of idealized female body. In a male-centric media world where women are "represented" in four different ways [2], Victoria's Secret Angels are undoubtedly the embodiment of the "myth of the woman's body". When the Victoria's Secret Fashion Show returned in 2024 after a five-year hiatus, it featured a "plus-size model" for the first time, immediately causing a buzz around the world. As Victoria's Secret's angel image is definitely a product of the "male gaze", such a change is widely seen as a break from the aesthetic norms of a male-dominated society. At the same time, on the Victoria's Secret Fashion Show in 2024, there are gorgeous returning of older retired models and wonderful renditions of transgender models, etc., the brand chose to break the Victoria's Secret Angels’ media image of the "perfect woman" deeply rooted in the hearts of whole society and is committed to opening the era of aesthetic diversity.

This study examines these recent transformations within the broader discourse of communication and gender studies, using Victoria’s Secret’s evolving brand image as a case study. Specifically, it explores the transformation of the Victoria’s Secret Angel—a symbol most representative of the brand’s identity—by analyzing the impact of an increasingly omnipresent media environment. Additionally, it investigates the feminist implications of these changes, assessing whether they signify genuine progress or a strategic response to shifting market demands.

2. Literature review

The evolution of Victoria's Secret's media image research in the past decade can be divided into three phases:

The first phase of research (2014-2017) focused on critiquing the cultural hegemony of its "perfect body" narrative. Dosekun has pointed out that the annual Victoria's Secret Fashion Show portrays the "angel" image as a single aesthetic paradigm of white, slim and young women through TV media [3], which is essentially a collusion between the male gaze and the commodification of the body [1].

In the second phase (2018-2020), against the backdrop of the #MeToo movement and the explosion of Body Positivity, research shifted to analyzing Victoria's Secret's market crisis. Tyler and Quek found that the decline in brand sales was directly related to consumers' demands for diversified aesthetics [4], and their adherence to traditional images was denounced as "aesthetic regression in the post-feminist era" [5].

The third phase (2021-2024) focuses on Victoria's Secret's "de-angelization" strategy on platforms such as TikTok and Metauniverse. Banet-Weiser criticizes its "plus-size model marketing" as essentially a new form of "trauma capitalism" that masks structural gender inequality through perverted inclusion [6]. A recent study points out that brands' use of algorithms to push "multi-body" content on short video platforms has led to "progressive fatigue" among Gen Z users due to the excessive commercialization of diversity [7].

The following views can be obtained from the integrated analysis of the above content:

First, brand image and feminist criticism reveal the deep contradiction of Victoria's Secret's media strategy. On the one hand, the image of "angel" strengthens body standardization through advertising and fashion shows and excludes non-white and non-slim body types [8]. On the other hand, its "sexiness is power" approach reduces feminism to individual consumption choices, serving the logic of capital appreciation [9].

Secondly, the research on image transformation in the all-media environment presents the tension between technology empowerment and capital discipline. Social media platforms such as Instagram have spawned user-led "anti-Victoria's Secret" content that deconstructs traditional aesthetics through selfies and memes [10]. The inclusion ads promoted by Victoria's Secret on TikTok have been criticized as "performative wokeness," essentially using algorithmic traffic to create false narratives of change [11].

Finally, the limitations of the disciplinary perspective gradually emerged. Communication studies focus on the influence of media technologies (such as algorithm recommendation and cross-platform communication) on brand crisis, while gender studies focus on cultural criticism of body discipline, but the two fail to integrate effectively. The cross-research between communication and gender theory is insufficient, and there is a lack of research on the dynamic mechanism of all-media.

3. Method

Combining content analysis and questionnaire survey, this paper aims to comprehensively investigate the change of Victoria's Secret angel media image from two dimensions of objective data and audience feedback. The specific methods are as follows:

3.1. Content analysis

This study objectively, systematically and quantitatively analyzes and describes the media image of Victoria's Secret angels through content analysis. A total of 15 annual Victoria's Secret fashion shows including 14 shows from 2005 to 2018 and one that returned in 2024 were determined to be the analysis unit. The research object of this study is all the models on the runway, rather than only the contracted models of Victoria's Secret brand. There were 618 samples in total. In this study, 46 model samples were deleted, and 572 samples were finally selected.

The statistics of this content analysis will be carried out from the five dimensions of gender, age, occupation, body size and nationality of previous Victoria's Secret angels. The gender index is mainly divided into models whose biological sex is female and models who are transgender or have undergone gender reassignment surgery. The age is calculated by the year of participating in the Victoria's Secret show. The index "body size" that is not easy to quantify will be presented by height and bust, waist and hip measurements. Considering that the concepts of "golden age" and "plus-size model" are difficult to define, this study only analyzes the changing trend of the data itself. Data sources such as model.com、 fashionmodeldirectory.com、web.archive.org etc. official website.

3.2. Questionnaire

The most prominent shortcoming of content analysis is that it cannot be used solely to determine the degree of influence of a certain content on the audience. Therefore, a small questionnaire survey on the mass communication effect of the Victoria's Secret Fashion Show is added to support the conclusion of this study. Through stratified sampling, 182 valid questionnaires were collected to ensure the balanced distribution of the respondents’ age, gender and occupation. The questionnaire structure mainly includes the following four parts: basic information of the respondents; Questions aiming at the cognitive effects of Victoria's Secret angel media image diversification on the audience, such as the frequency of audience's attention to Victoria's Secret Fashion Show ; Questions aiming at the attitude effect of the diversified media images of Victoria's Secret Angles on the audience, such as whether the media images of Victoria's Secret Angles meet the social definition of perfect body; and also questions aiming at the behavioral effects of Victoria's Secret Angel media image diversification on the audience, such as whether to buy and re-buy Victoria's Secret products. Through the design of the three sections of cognitive effect, attitude effect and behavioral effect, the influence of Victoria's Secret Angel media image on the audience can be more comprehensively reflected, so that the content of this research includes a complete closed loop of the production, dissemination and feedback of Victoria's Secret Angel media image.

4. Results

4.1. Content analysis

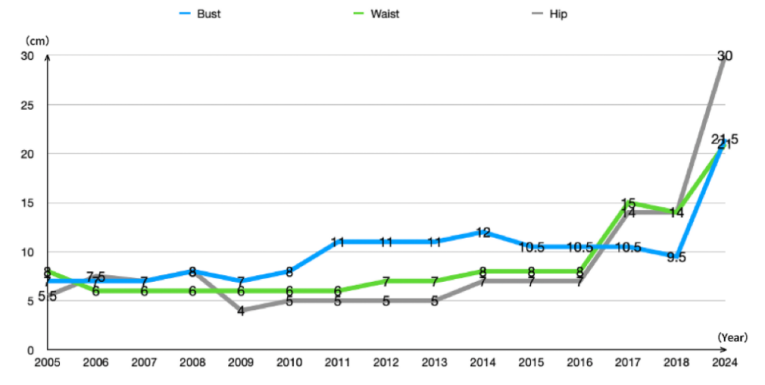

Through the quantitative analysis of the sample data, the diversified trend of Victoria's Secret angel media image is clearly and intuitively displayed (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1. Range of Victoria's Secret Angel body measurements (2005-2018, 2024)

The line chart shows the range of Victoria's Secret Angel body measurements (bust, waist, hip) between 2005 and 2018 and 2024. To account for the influence of individual extremes on the results, some data were removed. The range of the three dimensions has shifted from 7/6/4 in 2009 to 9.5/14/14 in 2018, showing an overall increasing trend, and more Victoria's Secret angels of different sizes have been on the Victoria's Secret Fashion Show. By 2024, Victoria's Secret Angel's range had expanded to 21.5/21/30, and the brand launched its first "Plus size Angel" collection (size 14-20).

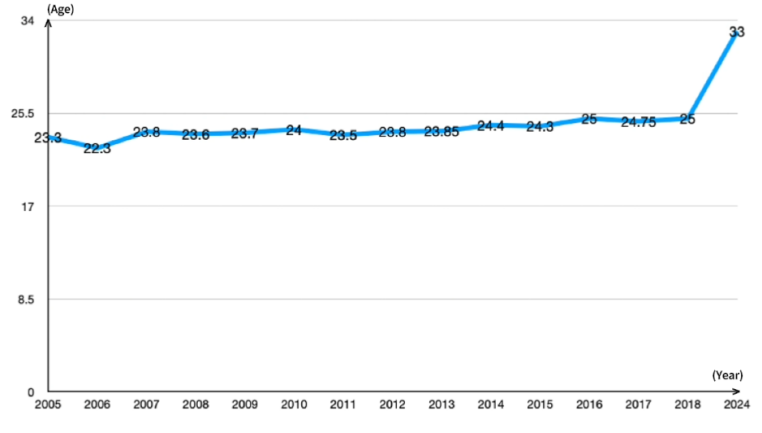

Figure 2. Average age of Victoria’s Secret Angles (2005-2018, 2024)

The statistical chart (Figure 2) of the average age of the angels of the past Victoria's Secret fashion show in the analysis unit (from Figure 2). The average age of models has increased from 23.3 years in 2005 to 25 years in 2018. In 2024, the average age of Victoria's Secret Angels exceeded 30 years old for the first time to reach 33 years old, and the introduction of models over 50 years old started the 'Silver-haired Angel' strategy.

At the same time, the statistical results show that the species composition of Victoria's Secret Angels also shows a trend of diversification. The proportion of non-white models rose from 15% in 2005 to 48% in 2018, covering diverse groups such as African Americans, Asians and Latinos. For example, Chinese supermodel Liu Wen was introduced in 2009, and Halima Aden, the first Muslim model wearing a hijab, was signed in 2024. This has led to a variety of angel appearances such as hair color and eye color.

In terms of gender composition, the first batch of transgender Victoria's Secret angels such as Alex Consani also appeared on the stage of the Victoria's Secret fashion show in 2024, opening a new era of gender diversity in the media image of Victoria's Secret angels. Moreover, Victoria's Secret Angels' occupations have evolved from modeling to actress, singer, TV/ social media personality and even professional basketball player (Elsa Hosk), equestrian (Willow Hand), etc.

4.2. Questionnaire

A total of 182 valid questionnaires were collected in this study, all of which had watched Victoria's Secret fashion shows, of which 55.5% were female and 44.5% were male, covering ages below 18 (7.14%), 18-29 (36.81%), 30-39 (32.97%), 40-49 (17.58%). People aged 50 and above (5.49%), staff (65.38%) and students (19.78%) accounted for a large proportion of the occupational composition, while the retired and others account for a small proportion.

According to the results of the survey on audience cognition, 50.55% of respondents said their primary source of learning about the Victoria's Secret fashion show and Angels was social media, much higher than other channels such as magazines, books or TV. From 64.84% of respondents who said they agree with the brand image of Victoria's Secret Angels and Victoria's Secret Fashion Show, to 68.13% of respondents believe that the media image of Victoria's Secret Angel meets society's definition of the perfect body, which reflects that the media image of Victoria's Secret Angel still represents the mainstream aesthetic of society.

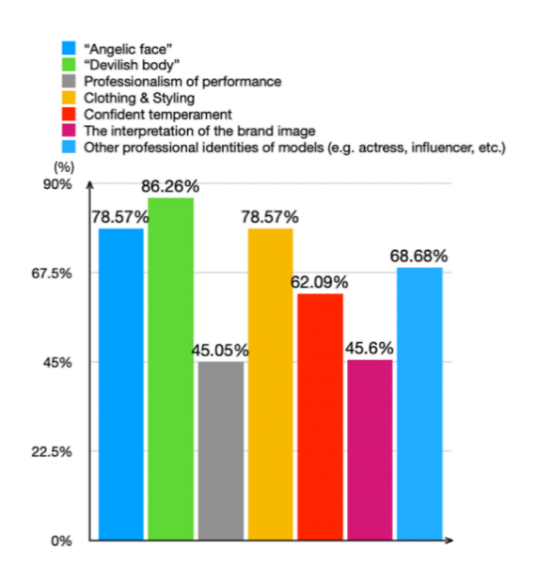

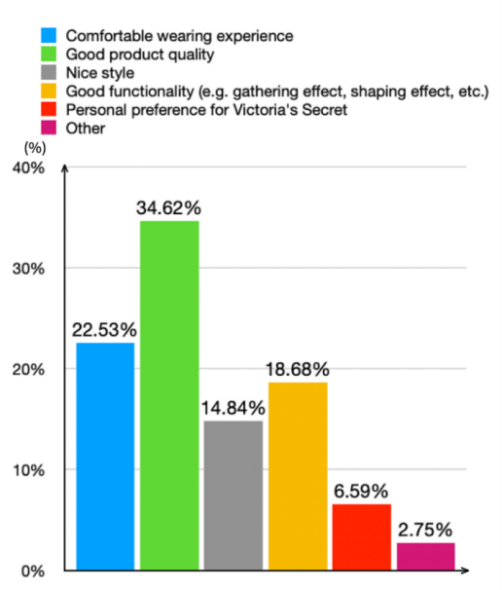

According to the results of the survey on audience awareness, more than 68% of respondents look forward to the diversity of Victoria's Secret's angel image, and there is a clear consumer demand for diversity in the brand image, reflecting society's growing concern for inclusion and diversity. Meanwhile, more than 68% of respondents said they have noticed the trend of diversity in Victoria's Secret's angel image, and more than 65% of respondents agree with this trend of diversity. The key factors of Victoria's Secret Angels' appeal to audiences are shown Figure 3.

Figure 3. The key factors contributing to the appeal of Victoria’s Secret Angels

Finally, the results of the survey on the effect of audience behavior show that 43.41% of respondents strongly agree that the image displayed by Victoria's Secret Angel arouses their desire to buy, and 63.19% of respondents say that they have purchased Victoria's Secret brand products, which shows that Victoria's Secret brand has a high market recognition and acceptance among the target audience. The main drivers of repurchasing products of Victoria's Secret are shown Figure 4.

Figure 4. The main drivers of repurchasing products of Victoria's Secret

In addition, more than 66% (56.04% strongly agree +10.44% strongly agree) of viewers said that the significant impact of Victoria's Secret's angel media image on their audience has prompted them to reshape their bodies through weight loss, weight gain or plastic surgery.

5. Discussion

The diversified trend of Victoria's Secret's angel media image from 2005 to 2018 and the leapfrog change in 2024 mark the complete shift of Victoria's Secret from "sexy hegemony" to "diversity and inclusiveness", which is both a response to feminist advocacy and a product of technological advancements in the all-media environment. Since the 2010s, the fourth wave of feminism has emphasized body autonomy and criticized the hegemony of a single aesthetic. Scholar Banet-Weiser points out that social media platforms such as Instagram become exhibition spaces for "non-standard bodies", forcing brands to respond [12]. For example, Victoria's Secret was boycotted by the #WeAreAllAngels movement in 2018 due to the lack of plus-size models, and finally launched a plus-size collection in 2024. Simultaneously, the diversity of race and age of Victoria's Secret Angels reflects the deepening influence of Intersectional Feminism. The introduction of Chinese supermodel Liu Wen to Victoria's Secret in 2009 and the signing of the first hijabs wearing Muslim model Halima Aden in 2024 were seen as a compromise to cultural diversity. Similarly, the introduction of the 'Silver-haired Angel' strategy of 2024 responds directly to feminist criticism of ageism [13].

The #MeToo movement in 2017 exposed gender exploitation in the fashion industry, and the sex scandal involving former Victoria's Secret executive Jeffrey Epstein also accelerated the transformation of the brand's image. The removal of the "angel" label in 2020 was seen as a move to cut patriarchal symbols [14]. The diversification of Victoria's Secret's angel media image is a progressive strategic deployment to break the male gaze and the commercialization of the body.

The essence of the transformation of Victoria's Secret is the strategic integration of feminist discourse by capital. Brands transform "inclusiveness" into new consumption symbols through symbols such as "plus-size angel" and "silver-haired model", but consumers also use the same symbols to initiate anti-hegemonic practices. For example, TikTok users mocked Victoria's Secret's "performable progress" with the hashtag #NotMyAngel, forcing the brand to commit to increasing its plus-size line to 20% [15]. Through Twitter hashtags (e.g. #VSFails) and TikTok challenges (e.g. "RealBodiesChallenge"), consumers can also directly intervene in the brand narrative. The all-media environment reshapes the power relationship between consumers and brands, and the supervision of public opinion and participatory culture of social media empower users. Although this reconstruction is full of contradictions, the all-media environment amplifies the voice of consumers for brand accountability, and makes "diversity and inclusion" rise from a marginal appeal to a necessary choice for business survival. Audiences are transformed from disciplined "objects of gaze" into actively engaged producers of meaning, forcing a fragile balance between commercial logic and body politics. The progressive nature of this transformation highlights the extent to which public discourse, facilitated by technological empowerment, has momentarily prevailed over corporate narratives.

6. Conclusion

Through a in-depth analysis of the media image of Victoria's Secret Angels, this study indicates that the image change of Victoria's Secret Angels reflects a comprehensive and diversified transformation trend in terms of body data, age, career background and other aspects. In addition, the gradual formation of an all-media environment has created unprecedented conditions for this transformation. The popularity of new media such as social media and short video platforms has enabled women to more directly participate in public discourse and express their own demands, thus accelerating the trend of diversification of Victoria's Secret Angel images.The all-media environment not only provides a broader platform for the spread of feminism, but also provides the necessary technical support and social conditions for the awakening of female consciousness and the diversified shaping of female images. Therefore, the diversified trend of Victoria's Secret angel images is not only the result of the development of feminism, but also an important driving force for the awakening of female consciousness in the all-media era.

However, this study acknowledges certain limitations. The data collected in the content analysis part of this paper is limited, and there may be errors in the analysis results of diversification trends. Future studies can collect more large, comprehensive and reliable data information for analysis. Due to limited conditions, the number of valid questionnaires collected in this questionnaire survey is relatively small, so the representative views of Victoria's Secret brand and Victoria's Secret fashion Show audience are limited. Future studies could expand the sample size to get more comprehensive feedback on views.

References

[1]. Gill, R. (2016). Post-postfeminism? New feminist visibilities in postfeminist times. Feminist Media Studies, 16(4), 610-630.

[2]. Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Screen, 16(3), 6–18.

[3]. Dosekun, S. (2015). For Western Girls Only? Post-feminism as transnational culture. Feminist Media Studies, 15(6), 960-975.

[4]. Tyler, M., & Quek, K. (2021). The fall of Victoria’s Secret: A feminist critique of neoliberal post feminism. Gender, Work & Organization, 28(3), 1070-1088.

[5]. Cherrier, H., & Türe, M. (2020). The aesthetics of exclusion: A critique of Victoria’s Secret’s postfeminist branding. Journal of Consumer Culture, 20(4), 431-450.

[6]. Banet-Weiser, S. (2023). Trauma Capitalism: Feminism and Brand Activism in the Digital Age. Polity Press.

[7]. Döring, N., & Mohseni, M. R. (2024). Virtual Bodies, Real Contradictions: Posthuman Feminism in Victoria’s Secret’s Metaverse Fashion Shows. Feminist Media Studies, 24(1), 1-18.

[8]. Barker, M. J., & Duschinsky, R. (2018). The Politics of Exclusion: Victoria’s Secret and the Reinforcement of Body Standards. Feminist Media Studies, 18(5), 789-805.

[9]. Gill, R., & Orgad, S. (2018). The shifting terrain of sex and power: From the ‘sexualization of culture’ to #MeToo. Sexualities, 21(8), 1313-1324.

[10]. Lupton, D. (2021). Digital Bodies: Self-Representation in the Age of Social Media. Polity Press.

[11]. Sobande, F. (2022). Woke-Washing and the Branding of Progressive Politics. Journal of Consumer Culture, 22(1), 246-264.

[12]. Banet-Weiser, S. (2018). Empowered: Popular Feminism and Popular Misogyny. Duke University Press.

[13]. Twigg, J. (2021). Fashion, the Body, and Ageism: Challenging the Exclusionary Practices of the Beauty Industry. Journal of Aging Studies, 57, 100936.

[14]. Tyler, M., & Quek, K. (2021). The fall of Victoria’s Secret: A feminist critique of neoliberal postfeminism. Gender, Work & Organization, 28(3), 1070-1088.

[15]. Banet-Weiser, S. (2024). Trauma Capitalism in the Age of Woke Brands. UC Press.

Cite this article

Han,X. (2025). The evolution of the media image of Victoria's Secret Angels: the collaborative development of feminism and the all-media environment. Advances in Social Behavior Research,16(3),64-69.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Social Behavior Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Gill, R. (2016). Post-postfeminism? New feminist visibilities in postfeminist times. Feminist Media Studies, 16(4), 610-630.

[2]. Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Screen, 16(3), 6–18.

[3]. Dosekun, S. (2015). For Western Girls Only? Post-feminism as transnational culture. Feminist Media Studies, 15(6), 960-975.

[4]. Tyler, M., & Quek, K. (2021). The fall of Victoria’s Secret: A feminist critique of neoliberal post feminism. Gender, Work & Organization, 28(3), 1070-1088.

[5]. Cherrier, H., & Türe, M. (2020). The aesthetics of exclusion: A critique of Victoria’s Secret’s postfeminist branding. Journal of Consumer Culture, 20(4), 431-450.

[6]. Banet-Weiser, S. (2023). Trauma Capitalism: Feminism and Brand Activism in the Digital Age. Polity Press.

[7]. Döring, N., & Mohseni, M. R. (2024). Virtual Bodies, Real Contradictions: Posthuman Feminism in Victoria’s Secret’s Metaverse Fashion Shows. Feminist Media Studies, 24(1), 1-18.

[8]. Barker, M. J., & Duschinsky, R. (2018). The Politics of Exclusion: Victoria’s Secret and the Reinforcement of Body Standards. Feminist Media Studies, 18(5), 789-805.

[9]. Gill, R., & Orgad, S. (2018). The shifting terrain of sex and power: From the ‘sexualization of culture’ to #MeToo. Sexualities, 21(8), 1313-1324.

[10]. Lupton, D. (2021). Digital Bodies: Self-Representation in the Age of Social Media. Polity Press.

[11]. Sobande, F. (2022). Woke-Washing and the Branding of Progressive Politics. Journal of Consumer Culture, 22(1), 246-264.

[12]. Banet-Weiser, S. (2018). Empowered: Popular Feminism and Popular Misogyny. Duke University Press.

[13]. Twigg, J. (2021). Fashion, the Body, and Ageism: Challenging the Exclusionary Practices of the Beauty Industry. Journal of Aging Studies, 57, 100936.

[14]. Tyler, M., & Quek, K. (2021). The fall of Victoria’s Secret: A feminist critique of neoliberal postfeminism. Gender, Work & Organization, 28(3), 1070-1088.

[15]. Banet-Weiser, S. (2024). Trauma Capitalism in the Age of Woke Brands. UC Press.