1. Introduction

The rise of far-right parties in Europe has become a central issue in both academic and policy field, exemplifying the “populist moment” in contemporary Western politics [1]. In multiple elections across Europe, far-right parties have been gradually moving from the political fringe to the center stage, not only securing parliamentary seats but even joining governing coalitions on multiple occasions. Recent national election in Europe results indicate that far-right parties are no longer marginal players in public opinion; they are now openly competing with center-right and center-left parties. For instance, Marine Le Pen, the National Rally (RN) candidate, secured 34% and 42% of the vote in the 2017 and 2022 French presidential elections, a significant leap from Jean-Marie Le Pen's 18% in 2002. In Italy’s 2018 elections, the far-right Five Star Movement (32.7%) and League (17.4%) formed a coalition. Similarly, Austria’s Freedom Party (FPÖ) secured 26% of the vote in 2017 and joined a governing coalition with the center-right Austrian People's Party (ÖVP). However, the performance of far-right parties varies significantly across countries. While some have rapidly expanded and attained governing power, others have remained marginal or even faded away. This raises a crucial question: Why do some far-right parties succeed in forming national governments while others fail to break out of political marginality despite similar socio-economic and political conditions? This paper proposes a comprehensive analytical framework integrating both supply- and demand-side factors, focusing on government effectiveness, party structure, and social demand to examine the key mechanisms shaping the rise and fall of European far-right parties.

2. Analytical framework

Government effectiveness, party structure, and social demand are distinct yet interdependent factors. Only when these elements interact together can they collectively shape the success or failure of far-right populist parties.

2.1. Government effectiveness

The legitimacy of a regime is influenced by its effectiveness [2]. In Western European electoral systems, government effectiveness is a fundamental variable affecting the rise and fall of populist parties. Efficient governance can swiftly respond to social crises and alleviate public dissatisfaction, thereby reducing the appeal of populist parties. Conversely, inefficient governance is often perceived as a sign of incompetent political elites, exacerbating social tensions and creating fertile ground for far-right parties. This paper adopts the World Bank’s “Government Effectiveness” index, which assesses the quality of public services, the independence of the civil service, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of government commitments [3]. When a country's government effectiveness score falls below the European average, it is categorized as low; otherwise, it is considered high.

2.2. Party structure

Political parties, as the most significant organizations in modern political life, must establish robust internal structures to achieve a high degree of institutionalization and effectively fulfill their functions. Scholars such as Duverger and Michels have emphasized that studying party organization is key to understanding party development [4]. While economic and cultural crises often provide a breeding ground for far-right parties, their long-term success depends on their ability to convert social grievances into lasting political capital. Stable internal organization, strong mobilization capacity, and authoritative leadership are crucial factor for political success. Empirical studies demonstrate that only far-right parties with robust organizational structures can effectively institutionalize sporadic electoral gains into sustained political success through disciplined party management [5]. Through both single-country and cross-national analyses of far-right parties, it has been found that well-organized parties perform better in opinion polls than loosely organized ones [6]. This study evaluates party structure through two indicators: (1) the number of party members and activists, and (2) leadership robustness. The scale of party members and activist cadres is a crucial component of a party's organizational structure. Parties with a larger number of activists are more effective in mobilizing voters through grassroots movements. A professional and long-term staff helps portray the party as competent, reliable, responsible, and predictable. At the same time, parties with more members and activists can demonstrate strong unity, which attracts voters. Leadership robustness primarily refers to whether a party has a strong and stable core leadership team to guide its long-term development. This is mainly analyzed by tracking the long-term evolution of internal power structures and factional changes within different parties to support the analysis in this study. These indicators help the author adopt a more systematic and quantitative approach when examining the diversity of branch political structures. A party's structure is considered strong if it meets two of these indicators, whereas if only one or fewer indicators are met, the party's organizational structure is deemed weak.

2.3. Social demand

The emergence and rise of far-right parties are closely linked to economic grievances and social identity crises. Economic grievances refer to widespread concerns over financial instability, often linked to welfare crises, global economic shocks, and job insecurity. Social identity crises arise when multiculturalism and post-materialist values challenge traditional social norms, triggering resistance to immigration and increasing support for far-right parties. Studies indicate that no far-right party has succeeded without mobilizing anti-immigration sentiment [7]. This study assesses social demand using data from the European Social Survey (ESS) and World Bank economic indicators. A high level of both economic and social grievances indicates strong social demand, while the absence of both suggests weak demand.

3. Scenarios for the rise of far-right parties

Based on the interplay of government effectiveness, party structure, and social demand, this study identifies eight scenarios for the emergence and development of far-right parties (see Table 1).

Table 1. Scenario configurations and electoral outcomes

Scenario | Government Efficacy | Party Structure | Social Demand | Party Outcome |

Scenario 1 | Low | Strong | Strong | National-level victory |

Scenario 2 | High | Strong | Strong | National-level victory |

Scenario 3 | High | Strong | Weak | Limited influence |

Scenario 4 | Low | Strong | Weak | Limited influence |

Scenario 5 | Low | Weak | Strong | Short-term rise, rapid decline |

Scenario 6 | Low | Weak | Weak | Marginalization or dissolution |

Scenario 7 | High | Weak | Strong | Short-term rise, rapid decline |

Scenario 8 | High | Weak | Weak | Marginalization or dissolution |

Source: Author-self made

Under conditions where incumbent governments demonstrate high governance efficacy yet face structurally robust far-right parties operating in high societal-demand environments (as depicted in Scenario 1 of Figure 1), far-right parties ultimately achieve nationwide electoral success. While effective governance may partially mitigate the immediate impacts of socioeconomic crises, far-right actors leverage their organizational strength and sophisticated electoral strategies to capitalize on heightened societal demands. In contexts of acute economic discontent and identity crises, voters exhibit heightened receptivity to radical policy proposals, enabling far-right parties to exploit elite-populace dichotomies and nativist rhetoric. Furthermore, their capacity for nationalized issue framing and cross-regional mobilization allows the translation of diffuse grievances into broad electoral coalitions. This suggests that even under high-governance conditions, the confluence of structural advantages and unmet societal demands creates necessary conditions for far-right ascendancy.

Hypothesis 1: A right-wing populist party with robust organizational infrastructure will achieve rapid nationwide success when either (a) host-state governance efficacy declines below critical thresholds or (b) societal demands exceed governmental response capacities.

Conversely, when strong far-right organizations confront high-governance states with low societal demands (Scenario 3), their expansion faces systemic constraints. Effective policy implementation satisfies majority voter needs, eroding the crisis narratives central to far-right mobilization. Absent acute grievances, their core nativist-identitarian agenda loses salience. Nevertheless, such parties may sustain localized influence through targeted issue entrepreneurship (e.g., immigration controversies), preserving organizational viability for future cycles.

Hypothesis 2: The absence of sufficient societal demand structurally constrains completely successful far-right mobilization, even when organizational capacity exists.

Notably, organizationally weak far-right parties demonstrate ephemeral breakthroughs under low-governance/high-demand conditions (Scenario 5). The “high demand-low response” dynamic creates temporary openings for anti-system mobilization. However, lacking institutional depth, such gains prove non-durable. These parties remain vulnerable to marginalization when either governance efficacy improves or demand structures shift (Scenarios 7-8), as evidenced by their inability to institutionalize protest votes. Ineffective crisis exploitation mechanisms permit only transient electoral success before accelerated marginalization—and eventual organizational dissolution—when either governance efficacy rebounds or societal demand structures undergo substantive reconfiguration.

Hypothesis 3: Right-wing populist parties with organizational deficiencies are frequently condemned to a boom-and-bust dynamic—experiencing meteoric electoral ascendance followed by accelerated institutional decay, often culminating in organizational dissolution.

4. Case analysis

To vertify the proposed framework of government effectiveness, party structure, and societal demand, this study analyzes six representative far-right parties: Brothers of Italy (FdI), Sweden Democrats (SD)Alternative for Germany (AfD), Vlaams Belang (VB) in Belgium, Britian National Party (BNP), and Gold Dawn in Greece. These parties represent the electoral performance of far-right parties in different political and economic contexts across Europe, making them highly significant for cross-national comparison.

4.1. The national victory: FDI and SD

4.1.1. Brothers of Italy

The September 25, 2022 Italian general election marked a watershed moment as Giorgia Meloni's far-right party Brothers of Italy (Fratelli d'Italia) secured approximately 26% of the vote, emerging as the largest parliamentary party and anchoring a right-wing coalition majority in both legislative chambers. Italy's ostensibly “sudden” rightward shift, however, reflects a protracted evolutionary process rooted in structural political realignments. Italy's governance capacity has faced sustained criticism in recent years, with its performance across multiple international metrics persistently lagging behind Western European averages. This chronic deficiency in governance efficacy has emerged as a key driver of the nation's sluggish economic growth and eroding societal trust, as evidenced by comparative OECD governance indices. The World Bank's Worldwide Governance Indicators reveal that Italy has consistently ranked lowest in government efficiency among Western European nations. According to 2021 data, Italy's governance efficacy score marginally surpassed some post-communist Eastern European economies but remained significantly below neighbors like Germany and France. This inefficiency is reflected in uneven public service quality, weak policy implementation, and persistent corruption and bureaucratic inefficiencies. Moreover, Italy’s multi-party political system is characterized by chronic instability. Over the past decade, Italy has undergone six government transitions, including three prime ministerial changes between 2021 and 2023. Such volatility disrupts policy continuity, forcing new administrations to address unresolved issues from predecessors. A Mestre CGIA Research Center report highlights Italy’s public administrative efficiency as Europe’s lowest, with excessive delays in permits and approvals. Inefficient bureaucracy imposes steep economic costs: SMEs annually incur €80 billion in administrative compliance expenses—a de facto hidden tax. Surveys indicate 73% of Italian entrepreneurs view bureaucratic procedures as major barriers, among the highest rates in Europe. Meanwhile, IMF data indicates Italy’s 2023 public debt reached 144% of GDP, the second highest in the EU after Greece. Collectively, weak governance has constrained Italy’s economic recovery and social stability, accelerating its marginalization within Western Europe’s political-economic framework.

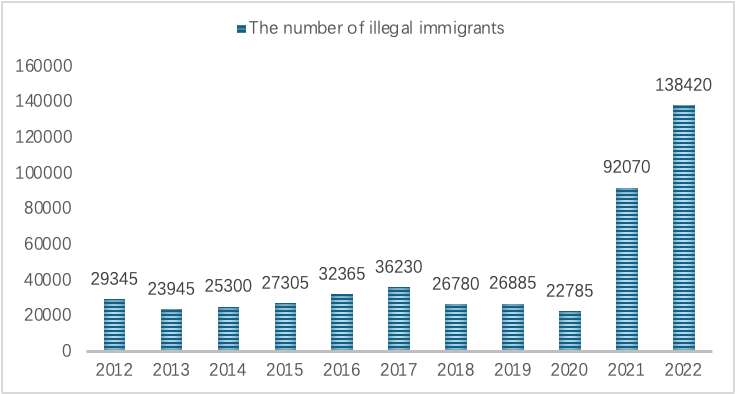

Second, unlike most far-right counterparts, Brothers of Italy (FdI) demonstrates distinctive organizational stability through cohesive leadership. Since its founding in 2012, Giorgia Meloni has consolidated her central leadership role without facing substantive intra-party challenges—a stark contrast to the recurrent factionalism and leadership struggles observed in comparable parties. This sustained strategic coherence has enabled FdI to maintain operational discipline and unified messaging across electoral cycles [8]. Brothers of Italy (FdI) inherited the organizational legacy of the Italian Social Movement (MSI) and National Alliance (AN), providing immediate access to established grassroots networks and leadership frameworks. By reactivating MSI/AN's local branch infrastructure, FdI rapidly developed nationwide electoral penetration. Strategic symbolic measures—notably the reintroduction of the flame emblem between 2014-2017—reinforced organizational cohesion among cadres and supporters. This organizational foundation enabled FdI's swift institutionalization as a major political force. Furthermore, the party cultivated an expanding membership base. Like most populist radical-right counterparts, FdI relies on its membership structure to consolidate territorial support through local activism and ideological indoctrination [9]. Transparency remains limited regarding official membership disclosures among Italian political parties. However, media-derived estimates suggest Brothers of Italy (FdI) maintained approximately 40,000 members prior to the pandemic. By 2020, its membership surged to over 130,000 (including 50,000 online registrations), surpassing center-right competitors Forza Italia (FI) and Lega (each around 100,000 members) (Redazione Cosenza Channel, 2021). Consequently, FdI ranks third in membership size, trailing only the center-left Democratic Party (400,000) and the Five Star Movement (200,000). Finally, from the perspective of societal demand, Italy's prolonged economic struggles and the impact of immigration have led to heightened social discontent. Economically, Italy has remained stagnant since being hit by the 2008 financial crisis. Despite the government's efforts to comply with the EU's austerity requirements, its government debt-to-GDP ratio increased from 106.2% in 2008 to 134.6% in 2019, while real GDP never recovered to pre-crisis levels. The COVID-19 pandemic further weakened the Italian economy: in 2020, GDP declined by 9%, the government deficit-to-GDP ratio reached 9.6%, and the debt-to-GDP ratio surged to 154.9% [10]. In terms of social identity, the large influx of immigrants has triggered intense identity anxiety. Since the 1990s, the number of immigrants in Italy has grown rapidly. The 1991 census recorded only 360,000 foreigners, accounting for less than 0.6% of the total population. By 2001, this number had quadrupled, reaching 2.3% of the population. By 2006, the foreign population continued to rise sharply, with the latest estimates indicating that approximately 2.7 million registered foreigners were recorded in the resident population registry, making up 4.5% of the total population [11]. As of 2021, ISTAT (Italian National Institute of Statistics) estimates indicate that 5,171,894 foreign citizens resided in Italy, constituting 8.7% of the total population. This aggregate includes naturalized foreign-born residents and undocumented migrants. Such a large wave of immigration has placed immense pressure on Italy’s society and welfare system, further fueling widespread xenophobic sentiments. Evidently, the combination of economic stagnation and the impact of immigration has heightened public discontent, with xenophobic tendencies becoming prevalent and directly influencing political dynamics. It was against the backdrop of government inefficiency and strong societal demands that Brothers of Italy, leveraging its strong organizational advantages, successfully transformed public grievances into political support, securing a nationwide victory.

Figure 1. The number of illgegal immigrants of Italy

Source: Statistics

4.1.2. Sweden Democrats

The Swedish case similarly validates the interplay between demand-supply dynamics and party structural factors in achieving national electoral success. Since the 2022 general election, Sweden's governing coalition has been sustained through parliamentary support from the far-right Sweden Democrats (SD), now the second-largest party in the Riksdag. Emerging from neo-fascist roots in 1988, SD remained marginalized by mainstream parties until surpassing the 4% electoral threshold in 2010[12]. Despite its classification as a radical right-wing populist party combining national conservatism and anti-immigration platforms, SD secured 12.9% of votes in the 2014 election—marking its entrenchment as a pivotal parliamentary actor [13]. After the 2022 parliamentary elections, although the Sweden Democrats (SD) did not enter the cabinet, they secured a “quasi-ruling party” status by signing a cooperation agreement with the ruling coalition, enabling them to influence the political landscape. The rise of the Sweden Democrats occurred against the backdrop of sustained high government efficiency alongside persistently rising social demands. Following World War II, Sweden established the Nordic welfare model, renowned as a system providing security “from cradle to grave” with government governance capacity and social welfare levels consistently ranking among the highest globally.

In the early 1990s, Sweden faced a severe economic crisis, prompting the government to implement a series of fiscal consolidation measures, including two “crisis response programs” in the autumn of 1992 and 1993. These initiatives aimed to reduce fiscal deficits and enhance corporate competitiveness. As Sweden gradually emerged from the crisis, the government leveraged the momentum to introduce structural reforms. These crisis-era industrial, tax, and fiscal reforms contributed to Sweden’s economic recovery, with its per capita income reaching parity with the Eurozone-19 average by 1995 and continuing to rise thereafter. By 2018, Sweden’s per capita GDP had reached $50,569, significantly surpassing the Eurozone-19 average of $43,435[14] .

Even in the face of the larger-scale global financial crisis of 2008, Sweden was able to swiftly recover by drawing on its past experiences, maintaining a strong developmental trajectory. Amid the debt crisis, a Fitch report indicated that global government debt had risen to nearly 60% of global GDP. Even countries with previously low government debt ratios, such as Finland, Germany, and Austria, experienced rapid increases in their debt burdens. However, Sweden’s government debt ratio exhibited only a brief period of increase before swiftly declining. After peaking at 45.5% in 2014, it continued to fall, reaching 38.8% by 2018. These reforms can be considered highly successful, laying a solid foundation for Sweden’s subsequent economic prosperity while also exemplifying the efficiency of the Swedish governmen.

Although Sweden successfully navigated multiple crises through swift responses and appropriate reform measures, the economic turmoil profoundly impacted even those within its high-welfare system. The real estate and financial crises eroded public confidence in the Swedish krona, prompting the Swedish National Bank (Riksbanken) to raise the benchmark interest rate to an unprecedented 500% in an attempt to restore trust in the economy. While Sweden’s real GDP declined by only 5% overall, layoffs and bankruptcies initially emerged in the construction sector before spreading to the retail industry, causing the unemployment rate to surge from 1.7% in 1990 to 8% in 1994[15].

During this period, Sweden’s decades-long liberal immigration policies had made it one of Europe’s most attractive destinations for migrants. The country’s total government expenditure as a share of GDP had already reached a staggering 60% by 1990[16] . Since the onset of the European refugee crisis in 2015, triggered by instability in the Middle East, the number of refugees arriving in the Nordic countries has surged. In 2015 alone, Sweden admitted 162,000 migrants and refugees—the second-highest absolute number in the EU after Germany and the highest per capita. Today, approximately one-fifth of Sweden’s population has an immigrant background [17]. In terms of public security, violent crimes involving refugees or individuals of Middle Eastern descent have become more frequent. In 2017, Sweden experienced a truck-ramming terrorist attack shortly after a similar incident in the UK, shattering the traditional stability and tranquility of the Nordic region. Economically, the financial burden of accommodating refugees has been considerable. At one point, Sweden resorted to renting luxury yachts as temporary asylum centers due to a shortage of shelter facilities, with a daily rental cost reaching as high as $93,000. Such fiscal policies, diverting significant public resources toward refugee support, have fueled dissatisfaction among Nordic taxpayers, who contribute heavily to the welfare system. By the late 1980s and early 1990s, the proportion of Swedes who believed that reducing refugee numbers was a good idea had already reached 65%. The combined pressures of economic strain and security concerns have accelerated the radicalization of Sweden’s general electorate, providing fertile ground for the rise of the far right. The nationalist and anti-immigration rhetoric championed by far-right parties gained considerable traction during this period. However, to translate this latent support into electoral success, structural adaptations within the party system were still required.

The Sweden Democrats’ (SD) breakthroughs in both national and European elections are best explained by the party’s increasingly professionalised organisational architecture [18]. Since the leadership transition in 2005, the new executive has systematically centralised authority, reinforcing internal and streamlining decision‑making processes. Under Jimmie Akesson, SD formally rebranded itself from a self‑described nationalist party to a social‑conservative one in 2011 and, in 2012, adopted a stringent “zero‑tolerance” policy on racism that led to the expulsion of numerous activists whose public statements violated the new line. These measures enabled the leadership to consolidate agenda‑setting power and to police ideological boundaries more effectively. Parallel to this strategic realignment, SD invested heavily in grassroots expansion: membership climbed from roughly 400 in 1994 to about 1,000 in 2003 and nearly 16,000 by 2015, while district organisations grew from 14 in 2007 to 24 in 2015 and municipal branches from 69 to 188 over the same period [19]. In Sweden’s high‑capacity state, this organisational mobilisation—combined with the popular discontent triggered by the post‑2015 migration crisis—has allowed SD to penetrate the mainstream party system and become a pivotal actor in shaping national political trajectories.

4.2. Limited influence:Afd and VB

4.2.1. Alternative für Deutschland (Germany)

Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) is one of Europe’s youngest far‑right formations to achieve sustained electoral traction. Founded in 2013, it swiftly normalised right‑wing radicalism within German party competition, despite ongoing factional strife among its leaders and regional branches [20]. The party managed to enter the European Parliament in the 2014 European Parliament elections by achieving 7.1% of the vote. Since then, AfD has not only entered all state legislatures but also became the third-largest political party in Germany with 12.6% of the vote in the 2017 federal parliamentary elections [21]. The party retained its parliamentary seats despite falling to 10.3% of the vote in the 2021 federal parliamentary elections (down 2.3 percentage points) and losing its status as the main opposition party. Notably, AfD’s core base of support has been concentrated in the eastern part of Germany, in the regions of the former German Democratic Republic (GDR), where its support is roughly double that of the west, and its share of the vote regularly exceeds 20% [22]. In the 2017 federal parliamentary elections, the party emerged as the most popular party in Saxony. The Alternative for Germany (AfD) faces a scenario characterized by high government effectiveness under the ruling party, a weak internal party structure, and low societal demand—conditions aligning with Scenario 4 outlined in Table 1. During the Merkel administration (2013–2021), Germany solidified its role as the European Union’s central leader through exceptional economic management and strategic engagement in European affairs. The economy exhibited robust growth, coupled with a steadily declining unemployment rate, which reached a historic low of 4.7% in 2016—the lowest level since German reunification [23]. Concurrently, the government implemented stringent fiscal policies, achieving a federal budget surplus in 2014 for the first time since 1969 without incurring new debt. Germany’s government effectiveness indicators consistently ranked among the highest in Europe, reflecting strong institutional performance. This period was marked by stable economic output, a resilient welfare system, and minimal social unrest, all underpinned by high governance efficacy.

After 2017, German voters shifted their priorities in federal elections from traditional concerns like education and social security to emerging issues such as refugee integration and cultural identity. This shift stemmed from profound socio-economic transformations, most notably Chancellor Angela Merkel’s 2015 decision to accept over one million refugees, which thrust immigration into the national spotlight [24]. The influx of Muslim communities—approximately 4 million by 2016, with 63% originating from Turkey, 14% from Southeastern Europe, and 8% from the Middle East—led to the formation of cultural enclaves, including 2,350 mosques, which critics described as “parallel societies”. These developments intensified debates over cultural cohesion, with 70% of voters expressing fears of societal fragmentation and 95% of AfD supporters claiming a perceived decline in German cultural identity. Despite heightened cultural tensions, economic dissatisfaction in Germany remained relatively low compared to other European nations. The Merkel administration’s adherence to the social market economy model ensured stability: from 2005 to 2017, GDP grew at an average annual rate of 1.4%, unemployment declined steadily, and the welfare system maintained robust coverage. According to the European Social Survey (ESS), public satisfaction with economic conditions ranked among the highest in Europe, contributing to subdued demand for radical policy changes. However, the AfD’s organizational weaknesses—such as fragmented leadership and limited grassroots networks—hindered its ability to transition from regional success to nationwide dominance.

Following internal turmoil in 2015, the Alternative for Germany (AfD) gradually achieved greater organizational stability and leadership cohesion, marked by structural reforms. First, the party adopted a dual leadership system. At its inaugural congress, the AfD elected a three-member national executive committee—comprising journalists Konrad Adam, Frauke Petry, and Bernd Lucke—on an equal footing. After entering the Bundestag in 2017, the party continued this model within its parliamentary caucus. From 2017 to 2021, co-chairs Alexander Gauland and Alice Weidel, both key electoral candidates, led the faction, overseeing internal coordination, group cohesion, and public representation. Post-2021 elections, Tino Krupalla and Weidel retained leadership roles, further institutionalizing this structure.

Second, the AfD embraced direct democracy mechanisms to broaden its grassroots appeal. As Reiser notes, unlike mainstream parties, the AfD implemented participatory practices such as online referendums for policy proposals and election manifestos, inviting members to vote directly. This collaborative approach to policy development—involving members in drafting, debating, and approving party programs—aimed to address public demands for greater political engagement [24]. By intensifying local campaigns and framing itself as a “voice of the unheard,” the AfD positioned itself as an alternative to hierarchical, bureaucratic mainstream parties.

These reforms yielded tangible results. The party’s inclusive processes, such as open congresses and emphasis on member input, signaled that member preferences were prioritized—a stark contrast to perceptions of traditional parties as detached elites. Consequently, AfD membership surged, particularly in regions disillusioned with established parties, even as other German parties faced declining enrollments. By 2021, the AfD had secured multiple state-level electoral victories, consolidating its role as a persistent force in German politics despite ongoing ideological tensions. Although the AfD still lags significantly behind Germany's traditional parties in terms of total membership, internal organizational reforms over the years have enabled the party to steadily expand its membership base. Consequently, the AfD has gradually established a certain level of influence beyond eastern Germany. After experiencing a brief decline, the number of party members has resumed an upward trend (as shown in Table 2).

Table 2. Changes in membership of major parties in Germany (2013-2021)

Year | AfD | SPD | CDU | CSU | GRÜNE | FDP | ||

2013 | 17,687 | 473,662 | 467,076 | 148,380 | 61,359 | 57,263 | ||

2014 | 20,728 | 459,902 | 457,488 | 146,536 | 60,329 | 54,967 | ||

2015 | 16,385 | 442,814 | 444,400 | 144,360 | 59,418 | 53,197 | ||

2016 | 26,409 | 432,706 | 431,920 | 142,412 | 61,596 | 53,896 | ||

2017 | 29,000 | 443,152 | 425,910 | 140,983 | 65,065 | 63,050 | ||

2018 | 33,500 | 437,754 | 414,905 | 138,354 | 75,311 | 63,912 | ||

2019 | 35,100 | 419,340 | 405,816 | 139,130 | 964,87 | 65,479 | ||

2020 | 32,000 | 404,305 | 399,110 | 136,014 | 107,307 | 66,032 | ||

2021 | 34,000 | 393,727 | 384,204 | 130,379 | 125,737 | 77,276 |

Source: Author's own made

4.2.2. Vlaam Belang

In recent years, the performance of Flemish political parties in Belgium in the federal elections has been in the spotlight, but in terms of actual data, their victories still show a limited success. In the 2024 federal election, for example, the Flemish Interest Party won 25 seats in the previous election (with about 16.03% of the vote), while this time around, although the number of votes realized rose slightly to 16.71%, the number of seats was reduced to 24. Therefore, although the Flemish Interest Party shows some positive changes in the electoral data, its actual influence in governmental decision-making is still very limited, providing a case for further validation of Scenario 4 in this paper. The limited success of Belgium's Flemish Interest Party reveals the country's triple political ecology - weakened government effectiveness, strengthened party structure and limited social needs. In terms of government effectiveness, Belgium's government effectiveness has always ranked at the bottom of the European scale in recent years, with government effectiveness scores fluctuating around 1.1-1.2. On the one hand, Belgium's unique federal structure allows the federal government to retain only symbolic powers, while substantive governance is vested in the regional governments, and there is a continuous game between the federal and local governments in terms of financial and administrative powers; on the other hand, Belgium has serious regional conflicts, and the gap between the positions of political parties from the Dutch-speaking region and the French-speaking region on issues such as finances and immigration not only led to the record 541 days of government vacancies in 2010-2011 but also led to the lack of a government after the 2024 election, which has led to the lack of a government for the next five years. It has also led to a crisis of cabinet formation after the 2024 elections. The inter-governmental and inter-regional crises have led to numerous government shutdowns and political crises in Belgium over the past decade, and have also served as an institutional breeding ground for the growth of the far-right. In terms of party structure, the VB party has a strong party structure that has developed over the years. Compared to the frequent changes of leadership in French-speaking parties, the Flemish Interest Party has a stable leadership formed since 2014 by Tom Van Grieken, who enjoys a high level of authority within the party. He not only controls the Party Executive, but also directly influences candidate nominations, policy making and disciplinary management. This effectively circumvents the “iron law of oligarchy” that prevails in Belgian political parties. The highest organizational body of the party is the Party Council, but in reality, the real decision-making power is held by the Party Executive Committee, which is responsible for policy decisions, campaign strategies and party discipline. The members of the Executive Committee are appointed by the party leader, and this organizational structure ensures that there is no strong and open factionalism in the party. In addition to this, the VB Party has adopted a modernized mass-party model that fosters a strong collective identity through social media and grassroots networks. Party members and supporters are encouraged to participate in party activities but have limited influence in decision-making, which reduces the potential for internal strife. Although the party experienced leadership turnover between 2007-2014, including a change of party leader and the departure of some core members from the party, which led to a large number of party members leaving and a decline in organizational membership of about 30% within this period. However, there was a recovery after the successful 2019 elections. The party has expanded its supporter base through social media and local mobilization strategies, rather than relying solely on formal membership. There has been a transition to a more flexible “hybrid mobilization model” that relies on social media, local organizations, and informal networks of supporters to increase its influence. By 2021, according to publicly available information, the party has enrolled 22,194 official members.It has 611,000 “likes” on Facebook, nearly 200,000 more than its closest rival, the Northern Veterans Party [25]. In terms of social needs, Belgium is characterized by “limited needs”. On the issue of immigration, since the refugee crisis in 2015, the Belgian government has strengthened government control, the number of immigrants has increased steadily, and a large proportion of immigrants are from within the European Union. Moreover, Belgium has a high level of social inclusion, with 65.5% of Belgians having a transnational background (e.g., one parent is a foreigner) and a high level of social acceptance of cultural diversity. Although 22% of Flemings consider immigration to be the biggest problem, this is much lower than in France (35%) and Germany (41%). In terms of economic dissatisfaction, Belgium boasts one of the lower Gini coefficients in Europe and globally, with a low level of economic dissatisfaction among the population, well below the average Gini coefficient value in the EU. In the ESS Social Survey, Belgium also has an upper-middle European ranking for economic satisfaction, with more than 70% of residents satisfied with their current situation from 2014 to 2024. Taken together, Belgium's social needs are low compared to the rest of Europe.

4.3. Shortlived surge and decline

4.3.1. British National Party (United Kingdom)

The fortunes of radicalright parties hinge on a shifting equilibrium between their organisational capacity and the external environment. Under the framework advanced here, a surge in societal demand or a deficit in government effectiveness can propel even weakly structured populist rightwing parties to rapid, shortterm breakthroughs—yet their fragile organisation prevents them from converting this momentum into durable political capital, leading instead to swift decline or outright dissolution.To test this mechanism, the section turns to two instructive cases: Britain’s British National Party and Greece’s Golden Dawn.

Within the framework developed here, the BNP’s collapse corresponds to Scenarios 7 and 8. During this period the United Kingdom enjoyed high government effectiveness, while the BNP’s organisational structure remained weak, and societal demand gradually ebbed from strong to weak. Specifically, from 2000 to 2014 the UK consistently ranked among the bestperforming European states on standard indicators of governmental effectiveness. “Third‑Way” policies paid handsome political dividends: between 1997 and 2007 the United Kingdom out‑performed most EU members on a range of economic indicators, and Labour secured three consecutive general‑election victories—the longest unbroken spell in office in the party’s history. The 2008 financial crisis briefly dented administrative performance, yet the UK’s relative autonomy outside the eurozone allowed it to enact more flexible rescue measures; its subsequent recovery outpaced that of continental Europe. Eurostat data show that the euro area as a whole did not regain its 2007 output level until 2017, whereas Britain surpassed its pre‑crisis GDP peak as early as 2013.After a short dip, the UK’s government‑effectiveness score rebounded to roughly 1.6—1.7. Overall, from 2000 to 2015 British governance exhibited a pattern of “rise, plateau, and minor fluctuations,” consistently placing the country in the global top decile—well above France or Italy, though still slightly below the Nordic leaders, Sweden and Denmark.

Second, the British National Party’s organisational architecture was chronically fragile. As John and Margetts observed, “Far-right parties in the UK tend to be internally fragmented and poorly managed. They have long been plagued by factional splits, leadership rivalries, and internal hostilities, which has prevented them from establishing a sustainable political tradition. [27]” (i)Leadership factionalism. Under Nick Griffin the BNP endured repeated schisms and power struggles, many sparked by clashes between Griffin and veteran activists loyal to the party’s founder, John Tyndall. During the party’s initial phase of local‑electoral growth (2001‑05) Tyndallites mounted an open rebellion; in 2007 several senior members of the Advisory Council launched a still more damaging revolt over mounting financial irregularities. The 2011 leadership challenge saw Griffin retain his post by a margin of just nine votes over MEP Andrew Brons; the failed putsch prompted a mass exodus of senior cadres, who urged others to defect to rival outfits such as the English Democrats. As John and Margetts observe, “Britain’s extreme‑right parties are chronically prone to factional splits, poor organisational management and internecine rivalry, leaving them without a sustainable political tradition.” (ii) Membership limitations. Although Griffin more than doubled the party’s headcount over a decade, the base remained thin. From a claimed 1,350 members in 1999 the BNP peaked at 13,009 in 2008—dwarfed not only by mainstream parties (the Liberal Democrats declared c. 90,000 members) but also by ideological counterparts such as France’s Front National (≈40,000). Persistent infighting accelerated attrition: high‑profile figures—including London Assembly Member Richard Barnbrook (expelled 2010) and MEP Andrew Brons (resigned after the 2011 contest), as well as strategist Mark Collett—left, eroding grassroots loyalty. By the time Griffin stepped down in 2014, the party faced de facto bankruptcy and a 75 per cent collapse in membership. (iii)Social isolation of the rank and file. BNP support networks were marked by pronounced ethnic segmentation: White‑British supporters seldom interacted with minority communities, particularly in ward‑level contests. This self‑imposed segregation further fragmented the party’s potential electorate, reinforcing the organisational vulnerabilities that ultimately undermined its survival.

Finally, in the wake of the global financial crisis the United Kingdom entered a gradual recovery from 2010 onward. A mix of austerity measures and structural reforms eased fiscal pressures, and from 2013 the economy began to rebound, recording brisk expansion in 2014. Both the OECD and the IMF identified the UK as the fastest‑growing economy in the G7. Falling unemployment tempered economic anxiety among lower‑ and middle‑income groups. As the “crisis narrative” on which the BNP thrived lost empirical traction, the party’s xenophobic and protectionist platform became less persuasive. After 2010 the EU intensified coordination on migration policy, while London imposed quotas on Eastern‑European entrants and tightened border controls, partially addressing anti‑immigrant sentiment. The Conservative government’s own “tougher migration” agenda further undercut the BNP’s distinctiveness, distancing the party from mainstream values and nudging voters toward actors perceived as more legitimate and competent rather than a marginal extremist fringe.

4.3.2. Golden Dawn

Another failed radicalright party—Greece’s Golden Dawn—provides a textbook test of Scenarios 5 and 6 in the present framework, demonstrating that even in a context of low government effectiveness, a party with a fragile organisation is likely to implode after a brief ascent. Golden Dawn’s breakthrough came at the height of the Eurozone turmoil: in the parliamentary election of May 2012, it captured 6.97 per cent of the vote and 21 of the 300 seats, catapulting it from the political fringe into the national legislature. Across the next four national and European elections its support plateaued in the narrow 6.3–9.4 per cent band. When Golden Dawn surged, Greece was caught in a perfect storm of low government effectiveness and intense societal demand. After the 2008 global crash, the 2009 sovereign‑debt meltdown, and the regional unrest triggered by the Arab Spring, Athens teetered on bankruptcy. Public debt soared, unemployment jumped from roughly 13 per cent in 2010 to 24 per cent in 2012, and youth joblessness rocketed from 33 to 55 percent. The World Bank’s Government Effectiveness index plummeted from 0.58 in 2008 to a mere 0.12 by 2015—one of the worst scores in Europe. Between 2008 and 2014 Greece endured intertwined economic, refugee and debt crises, fuelling mass anxiety and anger. A 2012 Eurobarometer poll found that 68 per cent of Greeks felt too precarious to plan for the future—an EU‑wide high—while 100 per cent described the economy as “bad” and 82 per cent as “very bad.” The Arab‑Spring and Syrian‑war refugee waves further strained capacity: by 2012 foreign nationals numbered about 975,000 (8.5 % of the population) versus an EU average of 6.6 %. Overburdened social services and mounting cultural tension made immigration a decisive issue for 27 percent of voters in the 2012 election [27]. Subsequent EU border‑control measures cut illegal Aegean crossings 63 per cent in the first quarter of 2016 and reduced new arrivals 82 per cent by end‑2017, easing demand over time.

Throughout Golden Dawn’s rise and subsequent marginalisation, its organisational profile remained consistently weak. The party’s fragility was most evident in a chronic leadership crisis. Since its founding Golden Dawn had been dominated by its founder, Nikos Michaloliakos, whose highly centralised, charisma‑based rule kept decision‑making tightly in his hands. This personalised control bred resentment and friction among cadres—tensions that intensified as the party’s violent activities and extremist rhetoric came under growing scrutiny. Revelations of aggression deepened the rifts. The 2013 murder of anti‑fascist rapper Pavlos Fyssas triggered an unprecedented legal crackdown: Michaloliakos and other leaders were arrested and charged with running a criminal organisation, gravely damaging the party’s public standing. The leadership’s response—deflecting blame onto “rogue individuals” rather than addressing systemic violence—failed to stem factional splits and only widened internal disillusion. Membership data are opaque—Golden Dawn never released official figures—but recruitment rules were onerous, requiring sponsorship by at least two existing members and a year of intensive activism. As infighting escalated and the leadership offered no credible strategy, defections mounted. In 2013 several senior figures, including long‑time stalwart Andreas Brons, quit over the party’s direction. Such departures exposed deep shortcomings in organisational management and leadership, further eroding cohesion and hastening Golden Dawn’s collapse.

5. Conclusion

By examining six emblematic cases, this article has unpacked the multilayered forces that shape the fortunes of Europe’s radical‑right parties, focusing on the interplay among party organisation, government effectiveness and societal demand. The trajectories of Fratelli d’Italia and the Sweden Democrats confirm Hypothesis 1: when organisational capacity is strong, a favourable condition on either the supply side (low state effectiveness) or the demand side (high grievance) is sufficient to propel a party to national victory. The experiences of Alternative für Deutschland and Vlaams Belang corroborate Hypothesis 2: even well‑institutionalised parties remain confined to “limited success” where societal demand is weak, unable to translate their structural advantages into nationwide dominance. Finally, the rapid boom‑and‑bust cycles of the British National Party and Greece’s Golden Dawn validate Hypothesis 3: in the absence of robust organisation, a radical‑right party is doomed to marginalisation once the external shock that fuelled its rise dissipates. The three‑factor framework advanced here not only reconciles these divergent outcomes but also supplies a transferable analytic tool for future research. Integrating organisational strength with the dual lenses of state capacity and citizen demand enriches our understanding of contemporary populism and highlights actionable levers for policy: bolstering governmental responsiveness, reducing socio‑economic insecurity and widening channels of political participation can blunt radical‑right appeal. Because party structure emerges as the pivotal mediating variable, comparative work should now explore how different organisational models perform across cultural settings and institutional designs. Moreover, as digital technologies increasingly reconfigure political mobilisation, investigating their impact on party building and public opinion in the radical‑right arena constitutes an urgent agenda for subsequent scholarship.

References

[1]. Brubaker, R. (2017). Why populism?Theory of Society, 46(1), 357-385.

[2]. Linz, J. J. (1978). Crisis, breakdown and reequilibration. In J. J. Linz & A. Stepan (Eds.),The breakdown of democratic regimes. Johns Hopkins University Press.

[3]. Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2010).The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues. World Bank.

[4]. Duverger, M. (1954).Political parties: Their organization and activity in the modern state(B. North & R. North, Trans.). Methuen.

[5]. Bolleyer, N., & Bytzek, E. (2013). Origins of party formation and new party success in advanced democracies.European Journal of Political Research, 52(6), 773-796.

[6]. Art, D. (2008). The organizational origins of the contemporary radical right: The case of Belgium.Comparative Politics, 40(4), 421-440.

[7]. Ivarsflaten, E. (2008). What unites right-wing populists in Western Europe? Re-examining grievance mobilization models in seven successful cases. Comparative Political Studies, 41(1), 3–23.

[8]. Puleo, L., & Piccolino, G. (2022). Back to the post-fascist past or landing in the populist radical right? The Brothers of Italy between continuity and change. South European Society and Politics, 27(3), 359–383.

[9]. Bolleyer, N. (2013). New parties in old party systems: Persistence and decline in seventeen democracies. Oxford University Press.

[10]. Eurostat. (2023). Euroindicators: Provision of Deficit and Debt Data for 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/17724161/2-23102023-AP-EN.pdf/307ffc6e-1bd7-0dbe-337b-7a85645c8e35

[11]. Favazza, S., & Pia, M. (2006). Measuring immigration and foreign population in Italy. In United Nations Expert Group Meeting on Measuring International Migration: Concept and Methods.

[12]. Elgenius, G., & Rydgren, J. (2017). The Sweden Democrats and the ethno-nationalist rhetoric of decay and betrayal. Sociologisk forskning, 3, 353–358.

[13]. Elgenius, G., & Rydgren, J. (2019). Frames of nostalgia and belonging: The resurgence of ethno-nationalism in Sweden. European Societies: The Far Right as Social Movement, 21(4), 583–602.

[14]. OECD. (2019). OECD Economic Outlook, No. 105.

[15]. Callaghan, J., Fishman, N., Jackson, B., & McIvor, M. (2009). In search of social democracy: Responses to crisis and modernisation. Manchester University Press.

[16]. Oxley, H., & Martin, J. P. (1991). Controlling government spending and deficits: Trends in the 1980s and prospects for the 1990s. OECD Economic Studies, 17, 145–189.

[17]. Sweden Population 2020. (2021). World Population Review. https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/sweden-population/

[18]. Rydgren, J., & van der Meiden, S. (2019). The radical right and the end of Swedish exceptionalism. Eur Polit Sci, 18, 439–455.

[19]. Sverigedemokraterna. (2015). Sverigedemokraternas verksamhetsberättelse 2013–2015. https://sd.se/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Verksamhetsberättelsen-2015-11-10.pdf

[20]. Arzheimer, K. (2019). “Don`t mention the war!” How populist right-wing radicalism became (almost) normal in Germany. Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(1), 90–102.

[21]. Heinze, A. S. (2020). Zum schwierigen Umgang mit der AfD in den Parlamenten: Arbeitsweise, Reaktionen, Effekte [Dealing with AfD in parliament: Legislative behaviour, responses, effects]. Zeitschrift für Politik-wissenschaft, 31(1), 133–150.

[22]. Weisskircher, M. (2020). The strength of far-right AfD in Eastern Germany: The east-west divide and the multiple causes behind “populism.” The Political Quarterly, 91(3), 614–622.

[23]. Germany. (2015). 2015 Article IV Consultation - Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Alternate Executive Director for Germany. IMF Country Report No. 15/187.

[24]. Gherghina, S. (2017). Direct democracy and subjective regime legitimacy in Europe. Democratization, 24(4), 613–631.

[25]. Sijstermans, J. (2021). The Vlaams Belang: A mass party of the 21st century. Politics and Governance, 9(4), 275–285.

[26]. John, P., & Margetts, H. (2009). The Latent Support for the Extreme Right in British Politics. West European Politics, 32(3), 496–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380902779063

[27]. Public Issue. (2012). The vote criterion in the 17 June 2012 elections. Published 19 June 2012. Retrieved April 28, 2025, from http://www.publicissue.gr/2039/criterion/

Cite this article

Wang,J.;Qiao,X. (2025). Government effectiveness, party structure, and social demand in the rise of far-right parties: the case of European far-right parties. Advances in Social Behavior Research,16(4),1-10.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Social Behavior Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Brubaker, R. (2017). Why populism?Theory of Society, 46(1), 357-385.

[2]. Linz, J. J. (1978). Crisis, breakdown and reequilibration. In J. J. Linz & A. Stepan (Eds.),The breakdown of democratic regimes. Johns Hopkins University Press.

[3]. Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2010).The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues. World Bank.

[4]. Duverger, M. (1954).Political parties: Their organization and activity in the modern state(B. North & R. North, Trans.). Methuen.

[5]. Bolleyer, N., & Bytzek, E. (2013). Origins of party formation and new party success in advanced democracies.European Journal of Political Research, 52(6), 773-796.

[6]. Art, D. (2008). The organizational origins of the contemporary radical right: The case of Belgium.Comparative Politics, 40(4), 421-440.

[7]. Ivarsflaten, E. (2008). What unites right-wing populists in Western Europe? Re-examining grievance mobilization models in seven successful cases. Comparative Political Studies, 41(1), 3–23.

[8]. Puleo, L., & Piccolino, G. (2022). Back to the post-fascist past or landing in the populist radical right? The Brothers of Italy between continuity and change. South European Society and Politics, 27(3), 359–383.

[9]. Bolleyer, N. (2013). New parties in old party systems: Persistence and decline in seventeen democracies. Oxford University Press.

[10]. Eurostat. (2023). Euroindicators: Provision of Deficit and Debt Data for 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/17724161/2-23102023-AP-EN.pdf/307ffc6e-1bd7-0dbe-337b-7a85645c8e35

[11]. Favazza, S., & Pia, M. (2006). Measuring immigration and foreign population in Italy. In United Nations Expert Group Meeting on Measuring International Migration: Concept and Methods.

[12]. Elgenius, G., & Rydgren, J. (2017). The Sweden Democrats and the ethno-nationalist rhetoric of decay and betrayal. Sociologisk forskning, 3, 353–358.

[13]. Elgenius, G., & Rydgren, J. (2019). Frames of nostalgia and belonging: The resurgence of ethno-nationalism in Sweden. European Societies: The Far Right as Social Movement, 21(4), 583–602.

[14]. OECD. (2019). OECD Economic Outlook, No. 105.

[15]. Callaghan, J., Fishman, N., Jackson, B., & McIvor, M. (2009). In search of social democracy: Responses to crisis and modernisation. Manchester University Press.

[16]. Oxley, H., & Martin, J. P. (1991). Controlling government spending and deficits: Trends in the 1980s and prospects for the 1990s. OECD Economic Studies, 17, 145–189.

[17]. Sweden Population 2020. (2021). World Population Review. https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/sweden-population/

[18]. Rydgren, J., & van der Meiden, S. (2019). The radical right and the end of Swedish exceptionalism. Eur Polit Sci, 18, 439–455.

[19]. Sverigedemokraterna. (2015). Sverigedemokraternas verksamhetsberättelse 2013–2015. https://sd.se/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Verksamhetsberättelsen-2015-11-10.pdf

[20]. Arzheimer, K. (2019). “Don`t mention the war!” How populist right-wing radicalism became (almost) normal in Germany. Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(1), 90–102.

[21]. Heinze, A. S. (2020). Zum schwierigen Umgang mit der AfD in den Parlamenten: Arbeitsweise, Reaktionen, Effekte [Dealing with AfD in parliament: Legislative behaviour, responses, effects]. Zeitschrift für Politik-wissenschaft, 31(1), 133–150.

[22]. Weisskircher, M. (2020). The strength of far-right AfD in Eastern Germany: The east-west divide and the multiple causes behind “populism.” The Political Quarterly, 91(3), 614–622.

[23]. Germany. (2015). 2015 Article IV Consultation - Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Alternate Executive Director for Germany. IMF Country Report No. 15/187.

[24]. Gherghina, S. (2017). Direct democracy and subjective regime legitimacy in Europe. Democratization, 24(4), 613–631.

[25]. Sijstermans, J. (2021). The Vlaams Belang: A mass party of the 21st century. Politics and Governance, 9(4), 275–285.

[26]. John, P., & Margetts, H. (2009). The Latent Support for the Extreme Right in British Politics. West European Politics, 32(3), 496–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380902779063

[27]. Public Issue. (2012). The vote criterion in the 17 June 2012 elections. Published 19 June 2012. Retrieved April 28, 2025, from http://www.publicissue.gr/2039/criterion/