1. Introduction

Minilateralism has become a defining feature of the Biden foreign-policy doctrine. The administration is increasingly relying on smaller, fit-for-purpose “coalitions of the willing” [1] to advance specific policy agendas on major crises around the world. Especially in the Indo-Pacific region, it has established a patchwork of smaller groupings, including the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (or Quad), AUKUS, U.S.-Japan-South Korea triad, and the trilateral initiatives with Japan and the Philippines. And in the Middle East, the US has been establishing and expanding minilaterals such as the I2U2 group between the US, Israel, the United Arab Emirates, and India.

What does minilateralism mean? Compared with multilateralism, it is a narrower and usually informal initiative intended to address a specific threat, contingency or security issue with fewer states (usually three or four) sharing the same interest for resolving it within a finite period [2].

From the US point of view, the rise of minilateralism is due to changing geopolitical circumstances and the ineffectiveness of existing multilateral platforms. Specifically, faced with the changing landscapes in the Indo-Pacific, the Biden administration is skeptical of multilateral systems like the U.N. and WTO, which are believed to be unable to tackle the problems concerning Russia-Ukraine, China-Taiwan, North Korea, Myanmar, etc. Besides, countering such countries framed as “autocratic camp” (China, Russia, Iran and North Korea) through minilateral organizations is popular across the American political spectrum.

Neoclassical realism is a relatively recent concept in international relations, only going back to a 1998 article in World Politics. In the article, Gideon Rose coined the term to synthesise the works of four scholars that he was reviewing: Michael E. Brown, Thomas J. Christensen, Randall L. Schweller and William Curti Wohlforth. Neoclassical realism incorporates both external and internal variables. On the one hand, it argues that the scope and ambition of a country’s foreign policy is driven by its place in the international system, specifically by its relative material power capabilities. Just as Zakaria says, “A good theory of foreign policy should first ask what effect the international system has on national behavior, because the most powerful generalizable characteristic of a state in international relations is its relative position in the international system.” [3] On the other hand, neoclassical realism investigates patterns in state behavior that interact with structural forces and it supplements structural realism by adding domestic factors. That’s because systemic pressures and incentives, which shape the broad contours and general direction of foreign policy, may not be strong or precise enough to determine the specific details of state behavior.

As one of the realist thinkings, neoclassical realism also determines security as primary objective of all states, and provides a more comprehensive analytical framework than its predecessors. Therefore, it may be a feasible perspective to dig into Biden’s minilateralism, which mainly emphasizes security issues. Besides, little research has been done on analyzing Biden’s minilateralism from the perspective of neoclassical realism, with only one related article on CNKI and none on JSTOR.

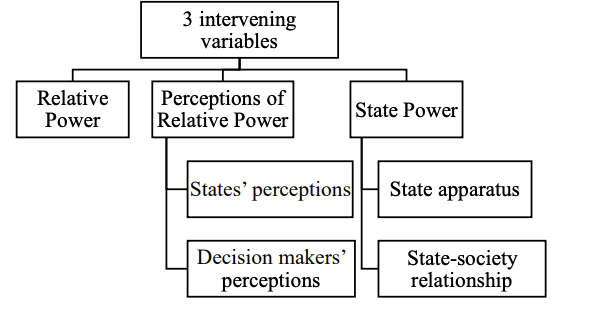

Since systemic pressures must be translated at the unit level, neoclassical realists propose 3 intervening variables to analyze the influence of the international system on state behavior. It’s noted that Schweller proposes a fourth variable: revisionism. He argues that a full theory of foreign policy should include the nature of states’ goals or interests, which is operationalized as the degree to which the goals or interests are status quo or revisionist, or whether states are satisfied with the existing distribution of international spoils, including the prestige, resources, and principles of the system [4]. However, the sources of revisionism remain undecided yet. Whether it is a domestic pathology or a product of the dynamics of the system is unclear. Therefore, it hasn’t been widely recognized as an intervening variable in neoclassical realism.

Therefore, this essay will use the following analytical framework (as shown in Figure 1) summarized from Rose G.’s article Neoclassical Realism and Theories of Foreign Policy [5] to analyze Biden’s minilateralism. The framework consists of 3 intervening variables. The first is “Relative Power”. The second is “Perceptions of Relative Power”, which includes “States’ perceptions” and “Decision makers’ perceptions”. The last is “State Power”, which includes “State apparatus” and “State-society relationship”.

2. Analysis

2.1. Relative power

The first intervening variable is “relative power”, the chief independent one. According to Wohlforth, “power” here refers to “the capabilities or resources…with which states can influence each other”. When it comes to the relationship between “relative power” and “state behavior”, “state behavior is an adaptation to external constraints conditioned by changes in relative power” [6]. Specifically, as relative power rises, states will seek more influence abroad; as it falls, states will scale back their actions and ambitions accordingly. It’s discovered that as middle powers rise, they are leveraging the momentum that minilateralism brings to the table to shape the international order. When it comes to Biden’s minilateralism, the formation of new groupings is primarily driven by the extraordinary rise of China, namely America’s decline in relative power. For example, in the case of the Quad, balancing the rising power of China is a core pillar of the cooperation and one of the main reasons behind the inception of the grouping. Moreover, the US’ act to align with other countries to strengthen its hegemonic order reflects both the decline of the US’ power in the region and reluctance to accept the waning of its hegemonic status because Washington cannot out-compete and confront China by itself. And the decline of US power will make it difficult to provide sufficient resources for the minilateral mechanisms, so the development of such minilaterals is unlikely to go entirely as the US wishes. For example, in April, the UN Security Council reconsidered Palestine’s membership application to join the UN. US allies such as France, Japan and South Korea voted in favor, while the US was the only one to veto the resolution.

So, what are the factors leading to the shifts in relative power? According to Kennedy, differentials in growth rates and technological change lead to shifts in the global economic balances, which in turn gradually impinge upon the political and military balances, thus causing shifts in the distribution of power [7]. It explains why Biden’s minilateralism is beyond military security. Having realized the importance of technology and economic development in relative power shifts, America has witnessed a trend of expanding cooperation on economic and technological spheres of influence. For example, technology cooperation has emerged within both the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) and the US-ROK-Japan trilateral partnership. Quad released 4 initiatives related to technology cooperation: Commercial Open Radio Access Networks (RAN) Deployment, Open RAN Security Report, Advancing Innovation to Empower Nextgen Agriculture (AI-Engage), and Quad Technology Business and Investment Forum [8]. In “Phnom Penh Statement”, the US-ROK-Japan trilateral partnership announced their commitment to advancing emerging technologies including biotechnology, artificial intelligence, quantum information science and technology, and open-RAN technology.

2.2. Perceptions of relative power

2.2.1. States’ perceptions

It should be noted that the shifts in “relative power” are “perceived” shifts in the distribution of power. Since there is no immediate or perfect transmission belt linking material capabilities to foreign policy behavior, foreign policy choices are made by actual political leaders and elites [5]. Therefore, it is their “perceptions of relative power” that matter, not simply relative quantities of physical resources or forces in being.

In fact, participants of such minilaterals led by America are considered as being “willing” and “like-minded” in certain issues, namely sharing similar “perceptions of relative power”. First, they are often united by common democratic ideals. Their perception of whether a power is a rival and potentially hostile hegemon doesn’t simply rely on its material capability, but takes common values and ideology into account. For example, despite the weaker power of North Korea, the cooperation between Washington, Tokyo and Seoul aims to counter the “autocratic enemy”.

Second, they share similar perceptions in responding to China’s rise and foreign policy behaviour. For example, the joint statements from the United States-Japan-South Korea summit in August 2023 and the United States-Japan-Philippines summit in April 2024 called out China’s “dangerous and aggressive behaviour” in the South China Sea, and strongly opposed any attempts by Beijing to “change the status quo” in regional disputes. Besides, ally countries may also hold opposite attitudes towards China. While the U.S. views China as a threat, many regional leaders view China as an opportunity. For example, using APEP (Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity) as a tool to combat China may drive a wedge between the U.S. and some countries the U.S. is trying to improve relations with on the American continent, which are expecting more investment and technology aid from China.

Besides, states hold different attitudes towards a minilateral. In the case of AUKUS, Australia and Japan think it may be a means to provide a “stable cooperation platform” should there be lapses in U.S. commitment or engagement because of emergencies elsewhere in the world or a U.S. domestic political impasse [9]. By comparison, Beijing warned that AUKUS is an outdated Cold War zero-sum mentality, which will only exacerbate arms race and hurt regional peace and stability.

2.2.2. Decision makers’ perceptions

Even different decision makers of a country will not have the same perceptions. The prospect of Donald Trump’s return to the US presidency casts a shadow over the sustainability of US-led minilaterals. Trump’s past record of withdrawing or threatening to withdraw from cooperative arrangements raise questions about the durability of US-led minilaterals. Trump is no internationalist but with long-standing impatience with alliances, and has never expressed support for the institutions of global governance. Apart from American leaders, perceptions of other involving decision makers also play a part. The inaugural United States-Japan-Philippines summit has materialised following the transition from the Rodrigo Duterte government to the Ferdinand Marcos Jr government in the Philippines. Under the Rodrigo Duterte government, it is doubtful whether a similar meeting would have taken place, who once threatened to end Manila’s military alliance with Washington, and opted for a bilateral strategy in the South China Sea.

As a result of decision makers’ subjective perceptions, sometimes such shifts are not captured by typical measures of capabilities. And states may have a hard time seeing clearly whether security is plentiful or scarce and may interpret partial and problematic evidence at hand in a subjective way.

In this sense, the variable of “perceptions of relative power” shows that neoclassical realists occupy a middle ground between pure structural theorists and constructivists.

2.3. State power

2.3.1. State apparatus

Here comes the third intervening variable. Neoclassical realists believe gross assessments of relative power are inadequate because national leaders may not have easy access to a country’s material power resources. According to Zakaria, foreign policy is made not by the nation but by its government. Therefore, what matters is state power, not national power. It acts as “a key intervening variable between the international challenges facing the nation and the strategies adopted by the state to meet those challenges” [10].

So, what does state power refer to here? It is “that portion of national power the government can extract for its purposes and reflects the ease with which central decisionmakers can achieve their ends” [3]. Similarly, Christensen defines national political power as “the ability of state leaders to mobilize their nation’s human and material resources behind security policy initiatives” [10]. Factors affecting state power include regime stability, political systems, and so on. In the case of the United States, it is a constitutional federal republic, in which the president (the head of state and head of government), Congress, and judiciary share powers, and the federal government shares sovereignty with the state governments. In this way, the central government presides over a federal state structure and a tiny central bureaucracy that could not get men or money from the state governments or from society at large. For example, US shipyards are running up to three years late in the AUKUS pact of Virginia-class submarines with Australia. That’s because only after the sitting president certifies to Congress that there will be no degradation of the US’s own undersea capabilities can the transfer of submarines occur. And the AUKUS legislation underwent great difficulties in winning support from across the US political spectrum, including from Republicans.

2.3.2. State-society relationship

Apart from the strength of a country’s state apparatus, its relation to the surrounding society also plays a role. That’s because those leaders and elites do not always have complete freedom to extract and direct national resources as they might wish and the strength and structure of states relative to their societies will affect the proportion of national resources that can be allocated to foreign policy. Such societies are represented by elite cohesion, financial groups and lobbies. The structure of the US political system allows special interest groups to wield outsized influence. They can lobby, make political contributions and spend unlimited amounts of money on advertisements and other messaging.

In the case of Palestine-Israeli conflict, James Zogby, president of the Arab American Institute, says pro-Israel groups have spent years “reinforcing narratives” to ensure Israel is seen as one of the US’s closest ideological partners, which ends up defining the turf and skewing congressional behaviour. As a result, Biden’s administration fails to get Israel to stop its military offensives in the southern Gaza city of Rafah while many of its minilateral allies vote for an immediate ceasefire.

3. Conclusion

The analytical framework consisting of 3 intervening variables summarized from Rose G.’s article Neoclassical Realism and Theories of Foreign Policy from the perspective of neoclassical realism helps explain the influence of the international system on state behavior, specifically the underlying reasons, defining features and development trend of Biden’s minilateralism. It can be concluded that (1) The formation of new groupings is primarily driven by America’s decline in relative power or the rise of China; (2) Participants of the minilateral organizations led by America share similar “perceptions of relative power”and are “willing” and “like-minded” in certain issues; Perceptions of all involving decision makers in the minilaterals play a part in policy shifts; (3) The federal state structure and a tiny central bureaucracy of America limits its state power to act in the minilaterals; The strength and structure of America relative to its societies affect the proportion of national resources that can be allocated to foreign policy.

Further, for Biden’s minilateralism, many in Europe are concerned that the Biden administration would prioritize Asia over Europe, continue the 'America First’ policy and create ongoing insecurity and competition among the US’ closest friends. And the goal of the US is believed to weave its minilateral mechanisms in the Asia-Pacific region into a US-led multilateral alliance, namely an Asia-Pacific version of NATO.

Therefore, America is supposed to practice minilateralism as a complementary mechanism to multilateralism instead of replacement. And minilateralism shall not be developed into covert unilateralism.

References

[1]. Gramer, R. (2024, April 11). Biden’s 'coalitions of the willing’ foreign-policy doctrine. Foreign Policy. https: //foreignpolicy.com/2024/04/11/biden-minilateralism-foreign-policy-doctrine-japan-philippines-aukus-quad/

[2]. Tow, W. T. (2019). Minilateral security’s relevance to US strategy in the Indo-Pacific: Challenges and prospects.The Pacific Review,32(2), 235–244.

[3]. Zakaria, F. (1998). From wealth to power: The unusual origins of America’s world role. Princeton University Press.

[4]. Schweller, R. L. (1994). Bandwagoning for profit: Bringing the revisionist state back.International Security,19(1), 19–26.

[5]. Rose, G. (1998). Neoclassical realism and theories of foreign policy.World Politics,51(1), 144–172.

[6]. Wohlforth, W. C. (1993). The elusive balance: Power and perceptions during the Cold War. Cornell University Press.

[7]. Kennedy, P. (1987). The rise and fall of the great powers. Random House.

[8]. Kim, D., & Orta, K. (2024). Minilateralism: A newfound approach to bolstering the US-Indo-Pacific partnerships in emerging technology. Wilson Center. https: //www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/minilateralism-newfound-approach-bolstering-us-indo-pacific-partnerships-emerging

[9]. Dominguez, G. (2023, June 6). Minilateralism: U.S. looks to small groupings to tackle shared security concerns. The Japan Times. https: //www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2023/06/06/asia-pacific/us-shall-security-groupings/

[10]. Christensen, T. J. (1996). Useful adversaries: Grand strategy, domestic mobilization, and Sino-American conflict, 1947–1958. Princeton University Press.

Cite this article

Wang,Z. (2025). Biden’s minilateralism from the perspective of neoclassical realism. Advances in Social Behavior Research,16(7),27-30.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Social Behavior Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Gramer, R. (2024, April 11). Biden’s 'coalitions of the willing’ foreign-policy doctrine. Foreign Policy. https: //foreignpolicy.com/2024/04/11/biden-minilateralism-foreign-policy-doctrine-japan-philippines-aukus-quad/

[2]. Tow, W. T. (2019). Minilateral security’s relevance to US strategy in the Indo-Pacific: Challenges and prospects.The Pacific Review,32(2), 235–244.

[3]. Zakaria, F. (1998). From wealth to power: The unusual origins of America’s world role. Princeton University Press.

[4]. Schweller, R. L. (1994). Bandwagoning for profit: Bringing the revisionist state back.International Security,19(1), 19–26.

[5]. Rose, G. (1998). Neoclassical realism and theories of foreign policy.World Politics,51(1), 144–172.

[6]. Wohlforth, W. C. (1993). The elusive balance: Power and perceptions during the Cold War. Cornell University Press.

[7]. Kennedy, P. (1987). The rise and fall of the great powers. Random House.

[8]. Kim, D., & Orta, K. (2024). Minilateralism: A newfound approach to bolstering the US-Indo-Pacific partnerships in emerging technology. Wilson Center. https: //www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/minilateralism-newfound-approach-bolstering-us-indo-pacific-partnerships-emerging

[9]. Dominguez, G. (2023, June 6). Minilateralism: U.S. looks to small groupings to tackle shared security concerns. The Japan Times. https: //www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2023/06/06/asia-pacific/us-shall-security-groupings/

[10]. Christensen, T. J. (1996). Useful adversaries: Grand strategy, domestic mobilization, and Sino-American conflict, 1947–1958. Princeton University Press.