1. Introduction

It is widely accepted by historians that the Industrial Revolution transformed the economic, social and political structure of the British state. Along with the adoption of new machinery and production methods, came more efficient production, economic growth and increased rate of urbanization.

Among the diverse industry factors transformed by the Industrial Revolution, the labor-intensive textile industry, which gradually shifted from domestic production to factory manufacturing, was one of the most typical representatives. Because the Industrial revolution promoted the large-scale production and trade of textiles, the UK became the main producer and exporter of textiles in the world.

At the same time, the textile industry is one of the most important employment areas for women. Many suggest that by the mid-17th century, the rise of factory manufacturing provided employment opportunities for a large number of women, especially in textile mills engaged in spinning and weaving. And for some women, it provides an opportunity to turn away from domestic work to earn a wage, leading to their economic independence. However, they often worked for long time, with low wages, in dangerous conditions, and lacked institutional protection of their rights. Especially in textile factories, women workers are often forced to work in crowded, unsanitary conditions, leading to health problems and occupational hazards. Moreover, regarding the wage, as some studies have shown, women's wages at that time were only one-third to one-half of men's wages [1]. Therefore, although the Industrial Revolution provided women with economic independence, the rise of factory manufacturing did not simultaneously change the status of women in society. On the contrary, the previous gender inequality was even enlarged rather than diminished dramatically. Women were subject to more restrictions and discrimination in a male-dominated society and have few opportunities to participate in decision-making and leadership positions.

This paper aims to explain the exploitation and oppression behind women's apparent employment and economic progress by focusing on the real life and work conditions of women during the Industrial Revolution and analyzing secondary literature.

2. Review of academic history

Much effort has been spent on study of women in the industrial revolution. Academic views could be roughly divided into two groups regarding the consequence and influence of the Industrial revolution on people’s daily lives. One is relatively bright, with industrialization creating new jobs and having a generally favorable effect on women, represented by scholars Graig Muldrew and Pinchbeck. Another view, however, is more critical of industrialization because of its negative impact on the status of women and on living and working conditions, represented by scholars such as Paul Minoletti, Stephen Nicholas and Deborah Oxley. Graig Muldrew argues that, during the Industrial Revolution, the textile industry was an industry mainly employed by women, and new factories and production methods provided more work opportunities for women. It also shows that women played an important role in the textile industry, engaged in spinning, weaving and other work, and became an important labor force during the Industrial revolution [2]. The drive of the Industrial Revolution modernized the textile industry, improved production efficiency, and provided women with more job opportunities and economic independence [2]. Therefore, it is concluded that the Industrial Revolution created new employment opportunities for women, broadened their employment scope and changed the traditional pattern of division of labor. Besides those arguing for increased employment opportunities, some scholars also suggest that industrialization would eventually create better living and working conditions for women. For example, Pinchbeck believes that increased productivity in the cotton trade will eventually create other jobs to replace spinning. This allowed women more leisure time at home and freed them from much of the drudgery and monotony of manual labor previously associated with industrial work under the domestic system. For women who work outside the home, this leads to better conditions, more opportunities and higher status [3].

Despite the optimistic and bright depiction of women’s lives during the age of industrial revolution, some scholars made exact opposite arguments, claiming that the growth of economy or the progress of production overall did not necessarily ameliorate the living conditions of the people. Paul Minoletti's, for example, explores the impact of the shift in factory production in the British textile industry from 1760 to 1850 on women's employment opportunities. The authors note that in addition to economic factors, gender ideology also plays an important role in the labor market. As work organization became more formalized and hierarchically institutionalized throughout the study period, gender perceptions had a clear and growing influence on the functioning of the labor market. But gender ideology, union exclusion, and underinvestment in women's human capital limit women's employment opportunities and earnings. The Industrial Revolution led to the division of labor and limited wages for women in factory production, especially in jobs that required manual labor. The same article states that gender perceptions have had an important impact on women's employment opportunities in the factory textile industry, and that this impact has gradually intensified in the process of industrialization [4]. Similarly, in Stephen Nicholas and Deborah Oxley's article, the authors demonstrate that the Industrial Revolution had a negative impact on women of England by affecting their living conditions. The authors highlight that instead of having more opportunities in the job market, English women actually faced reduced employment opportunities, unfair wages, and poor working conditions during the Industrial Revolution, which led to their economic hardship and lowered their social status even further. In addition, the authors argue that industrialization has intensified the dynamics within the family and limited the positions of women within the family. Studies have shown that women in England experienced a decline in living standards during this period, including a loss of height and an increase in literacy rates, reflecting problems such as inadequate nutrition and deteriorating health they faced [5]. It can be concluded from the history of literature on this issue that there are great differences in the current research on women in the industrial revolution, and their research methods are also completely different.

3. The shift in women's employment

Among the positive points is the emphasis on two benefits for women during the Industrial Revolution one is the increase in employment opportunities and the other is the increase in economic independence. But when we talk about employment, the undeniable problem is that women have unequal access to resources. The distribution process of markets, states and families discriminates against them. However, these processes are not constant in the face of economic change. Industrialization opened up new opportunities, but closed down other traditional employment opportunities [6]. Granted, we can't ignore the fact that the Industrial Revolution did increase employment opportunities for women Graig Muldrew analyzes the potential employment population, and concludes that the potential employment by 1770 was about 75 per cent of all women over the age of 14 in the Britain.” [2] It is also true that the same women made many contributions to the Industrial Revolution, such as women's participation in the accumulation of capital, the reproduction and development of human capital, the mediation of families and enterprises, and the definition of gender roles [7]. However, we cannot ignore the decline of traditional employment opportunities for women during the industrial period, because traditional female labor methods have not changed, and the division of sex between men and women at work has been greatly strengthened [8]. First of all, during this period, the enclosure movement was in full swing, as Thomas More called the phenomenon of "sheep eating men," [9] Much of women's agricultural labor, or traditional "women's labor," was lost, including activities such as collecting and raising pigs and cattle [5]. In the area around Bury St Edmunds, for example, in the descriptions of women from this period, it can be seen that they were mainly engaged in such jobs as stone-picking, weeding and dropping corn [10]. However, starting in 1780, women's employment began to be restricted by Industrial Revolution and enclosure, so at this time a large number of women had to enter the low-paid female work class [5]. At Courtauld's mills in Essex in the early 18th century, for example, many of the female workers displaced by changes in the organisation of agricultural production and the mechanization of wool spinning entered the mills for low-wage work [7]. Thus, during the industrialization period, women workers were still engaged in traditional economic sectors, such as weaving within the family, while women's labor participation may decline after marriage, especially during the industrialization era [8]. From the above, we can see that a large number of women have lost traditional employment opportunities, and the traditional textile family industry is also disappearing. However, the traditional women's labor has not changed, but they have entered the low-income working class because of the enclosure movement and industrialization. This low income and the entry of the working class did not bring much benefit to women nor did it increase women's economic independence. On the contrary, these changes in employment opportunities strengthened the exploitation of women and worsened the living environment of women. Therefore, the following article will explore the real situation of women in the life and work environment.

4. The working and living conditions of women during industrial revolution

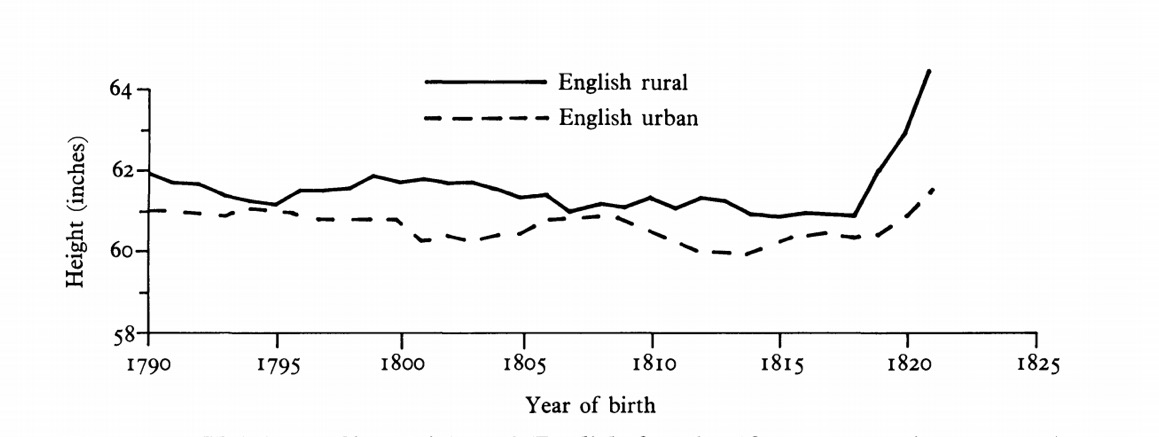

As mentioned above, the growth of employment opportunities for women has been limited to new industrial employment opportunities, but traditional employment opportunities have disappeared. Therefore, women did not have much positive influence on life and work during the Industrial Revolution. On the contrary, a large number of women worked in poor conditions and low-income economic conditions during this period. Moreover, due to the long-existing gender inequality in pre-modern age, the rapid transformation of methods of production as well as the social norms during the age of industrial revolution, did not necessarily benefit women, who, as a non-privileged group, were marginalized and exploited in both domestic and social spheres. First of all, the living environment for women is extremely harsh. From the perspective of women's own physical conditions, height is a good factor to determine the quality and level of life. However, from the distribution of height changes of rural and urban women in England (Figure 1), the height gap between urban and rural women was always very large from 1795 to 1817, and even a difference of two inches around 1800, which seriously reflected the insufficient nutrition of women in rural areas. Similarly, the height of urban women did not increase significantly during the Industrial Revolution, but remained stable and declined in the early 19th century. At the beginning of the 19th century, the average height of rural women was 61.75 inches, but by about 1815 it had fallen below 61 inches. Rural men, by contrast, fell only a quarter of an inch, from 66 inches in 1800 to 65.75 inches in 1815 [5]. This raises concerns about the uneven distribution of resources within households. Therefore, during the Industrial Revolution, women did not benefit from industrialization, but there was a decline in the industrial Revolution, and the decline was much higher than that of men, so it can be seen that their living environment and nutrient intake also showed a downward trend. And there's plenty of evidence that women and children did not eat as well as men. According to Oddy's report that women and children eat less meat than men, women acquiesce because the "husband" wins the bread and must have the best food [11]. In the study, it was found that adult men were given more cheese, milk and more rich foods, while women and children were content to add small amounts of milk to tea and porridge, and use small amounts of daily necessities to survive [12]. Therefore, it can be seen that the diet level of British women during the Industrial Revolution was lower than that of men, and it was even difficult to maintain the basic level of daily nutrition.

The working conditions for women were just as bad. The exploitation of women and children led to the loss of their rights, which made it easier for women to engage in household, primitive industry and industrial work. Due to industrialization, women lost their traditional jobs and had to enter factories and the bottom industries of industrialization, thus becoming "sweated" trades [13]. The death of Mary Walkery, who was employed by a very good tailor shop and was forced to work for 26.5 hours straight in a room full of 30 young women, is a good example of this [1]. Meanwhile, according to the Nottingham General Disoensary study of 600 women aged 17 to 24 who worked for lacemaker found that tuberculosis cases had increased 62-fold over a decade [1]. It can be clearly seen that the working environment of women at work is very bad, which has caused a threat to the safety of women's lives. Secondly, the wage level of women was generally low during the Industrial Revolution, and there was a large wage gap between women and men. This gap typically manifests as women earning between one-third and two-thirds of men's wages, depending on the type of job and location [14]. The study also found that women generally spend less time in market labor because they also have family responsibilities, which results in shorter working hours on average, which affects their income levels [14]. Therefore, women's salary during the Industrial Revolution was greatly limited, and they not only had to take care of their work but also had to take care of their families, so women's life pressure would gradually increase. At the same time, the social pressure on women was also increasing. At that time, working women, especially factory workers, were often scapegoats for social ills and blamed for moral degradation and social corruption. This stereotype creates a negative perception of the role of women in industrialized societies [15]. From this, we can see that women workers are generally paid less than men in the factory, the working environment is bad, and after the industrial Revolution, women still have to bear the family responsibility, and the social pressure on women is gradually increasing. So the poor living and working conditions of women during the Industrial Revolution gradually emerged before our eyes.

5. Conclusion

The Industrial Revolution created much discrepant experiences for the contemporaries. From what I have said above, we can see that under the social conditions at that time, although women were given a large number of employment opportunities, they were still faced with extremely bad living and working conditions, and their income and social pressure would gradually increase. It also reflects from the side the exploitation of women's work and the miserable living environment at that time.Although the Industrial Revolution added new employment opportunities for women, we can see that many traditional employment opportunities were lost. At the same time, women had to move from traditional female occupations to new occupations in the factories. However, the low wage and unbearable working conditions demonstrated that the exploitation of women and gender discrimination also made their way into the industrial age. Moreover, the unequal accessibility and distribution of resources within the family have led to great social and life pressure for women., Therefore, with the acceleration of the industrialization process during the Industrial Revolution, women, as a non-privileged group, had already existed gender inequality in the early modern period, which resulted in further exploitation of women by families and society.

References

[1]. Foster, John Bellamy, and Brett Clark., (2018). "Women, nature, and capital in the industrial revolution."Monthly Review, 69.8, 1-24 .

[2]. Muldrew, Craig., (2012). "'Th'ancient Distaff’and 'Whirling Spindle’: measuring the contribution of spinning to household earnings and the national economy in England, 1550–1770 "The Economic History Review65.2, 498-526.

[3]. Ivy Pinchbeck. (1930). Women Workers and the Industrial Revolution, 1750-1850. George Routledge.

[4]. Minoletti, Paul., (2013). "The importance of ideology: the shift to factory production and its effect on women's employment opportunities in the English textile industries, 1760–1850."Continuity and Change, 28.1 , 121-46.

[5]. Nicholas, Stephen, and Deborah Oxley., (1993). “The Living Standards of Women during the Industrial Revolution, 1795-1820.”The Economic History Review, vol. 46, no. 4, 723–49.

[6]. Humphries, Jane., (1991). "" Lurking in the Wings...": Women in the Historiography of the Industrial Revolution."Business and Economic History, 32-44.

[7]. Tilly, Louise A., (1994). "Women, women's history, and the Industrial Revolution."Social Research, 115-137.

[8]. Cohen, Marjorie., (1984). "Changing Perceptions of the Impact of the Industrial Revolution on Female Labour."International Journal of Women's Studies, 7.4, 291-305.

[9]. Thomas More. (2002). Utopia. Cambridge University Press.

[10]. 'Report on the Employment of Women and Children in Agriculture’ (1843),Boston Medical And Surgical Journal, DOI: 10.1056/NEJM184307260282501.

[11]. Oddy, D., (1976). 'The nutritional analysis of historical evidence: the working class diet.’ in D. Oddy and D. Miller, the making of the modern British diet , 214-31.

[12]. Shammas, C., (1984). 'The Eighteen-century English diet and economic change’Exploration in Economic History, 21 , 254-69.

[13]. Humphries, Jane., (1990). "Enclosures, common rights, and women: The proletarianization of families in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries."The Journal of Economic History, 50.1 , 17-42.

[14]. Burnette, Joyce., (1997). "An investigation of the female–male wage gap during the industrial revolution in Britain."The Economic History Review50.2, 257-281.

[15]. Clayton, Ashni., (2020). Words About Women: Male Authors’ Portrayal of Female Characters in the Industrial Revolution. Diss. University of Colorado Boulder.

Cite this article

Wang,B. (2025). Experiencing the industrial revolution: the living and working condition of women in 18th century Britain. Advances in Social Behavior Research,16(11),23-26.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Social Behavior Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Foster, John Bellamy, and Brett Clark., (2018). "Women, nature, and capital in the industrial revolution."Monthly Review, 69.8, 1-24 .

[2]. Muldrew, Craig., (2012). "'Th'ancient Distaff’and 'Whirling Spindle’: measuring the contribution of spinning to household earnings and the national economy in England, 1550–1770 "The Economic History Review65.2, 498-526.

[3]. Ivy Pinchbeck. (1930). Women Workers and the Industrial Revolution, 1750-1850. George Routledge.

[4]. Minoletti, Paul., (2013). "The importance of ideology: the shift to factory production and its effect on women's employment opportunities in the English textile industries, 1760–1850."Continuity and Change, 28.1 , 121-46.

[5]. Nicholas, Stephen, and Deborah Oxley., (1993). “The Living Standards of Women during the Industrial Revolution, 1795-1820.”The Economic History Review, vol. 46, no. 4, 723–49.

[6]. Humphries, Jane., (1991). "" Lurking in the Wings...": Women in the Historiography of the Industrial Revolution."Business and Economic History, 32-44.

[7]. Tilly, Louise A., (1994). "Women, women's history, and the Industrial Revolution."Social Research, 115-137.

[8]. Cohen, Marjorie., (1984). "Changing Perceptions of the Impact of the Industrial Revolution on Female Labour."International Journal of Women's Studies, 7.4, 291-305.

[9]. Thomas More. (2002). Utopia. Cambridge University Press.

[10]. 'Report on the Employment of Women and Children in Agriculture’ (1843),Boston Medical And Surgical Journal, DOI: 10.1056/NEJM184307260282501.

[11]. Oddy, D., (1976). 'The nutritional analysis of historical evidence: the working class diet.’ in D. Oddy and D. Miller, the making of the modern British diet , 214-31.

[12]. Shammas, C., (1984). 'The Eighteen-century English diet and economic change’Exploration in Economic History, 21 , 254-69.

[13]. Humphries, Jane., (1990). "Enclosures, common rights, and women: The proletarianization of families in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries."The Journal of Economic History, 50.1 , 17-42.

[14]. Burnette, Joyce., (1997). "An investigation of the female–male wage gap during the industrial revolution in Britain."The Economic History Review50.2, 257-281.

[15]. Clayton, Ashni., (2020). Words About Women: Male Authors’ Portrayal of Female Characters in the Industrial Revolution. Diss. University of Colorado Boulder.