1. Introduction

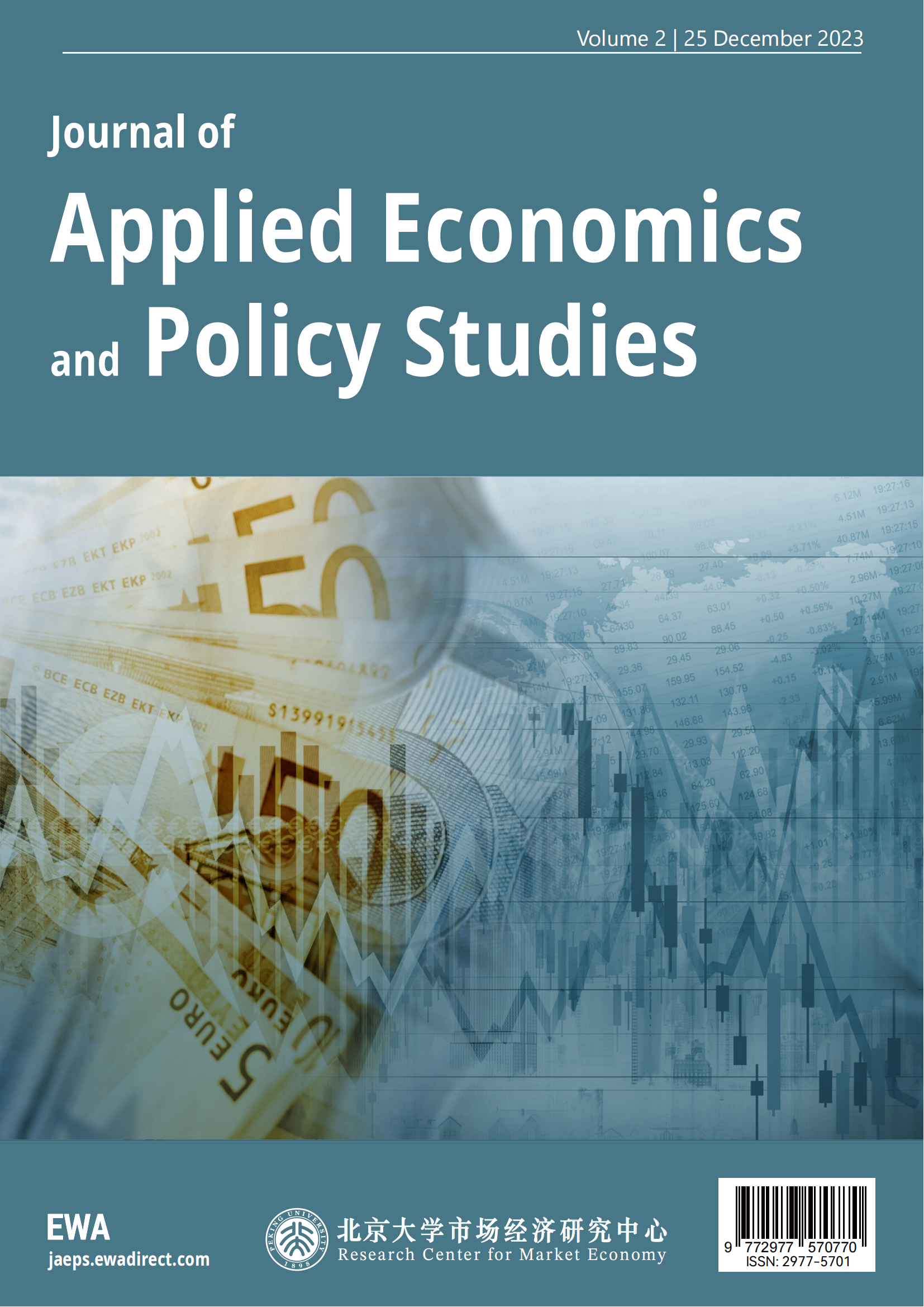

2013 Chinese President Xi Jinping proposed the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The BRI is “a vision and strategy for transforming the economic landscape in Asia, Eastern Europe, and Africa in the coming decades with the help of a commitment to build infrastructure, energy, and telecommunication sectors” [1]. The BRI covers nearly 65% of the world’s population and 1/3 of the world’s GDP [2]. The significance of the BRI has been described by many commentators, such as “China’s grand connectivity project” [3], and “a globalization 2.0” [4]. Generally, the BRI has two belts land belt that covers nearly all the counties of the original Silk Road in Eurasia and a maritime belt that links China’s port facilities with the African coast, the Suez Canal, and the Mediterranean [5]. Inside, the economic corridors address BRI’s connectivity rationale [6].

Figuer 1: MERICS China Mapping (Source: Mercator Institute for China Studies, 2015)

We can view the BRI as a project generating networks and regions. Networks integrate and form areas and parts as a geographic arena for creating and maintaining networks [7]. In a network, other members’ participation value is called network value. As the number of members grows and network value increases, silent network pressure prevents members from leaving the network. This is network effect pressure. The lock-in effect is the crucial dynamic produced by network effect pressure [8]. “Lock-in occurs when users become unable to unplug from a network without incurring a loss and so become ‘locked’ into the network” [9].

Since 2013, there has been much research and literature about the BRI from various aspects; however, the research on the connection between the BRI and network theory is underdeveloped. In addition to the literature gap, whether the BRI can generate network effects and lock-in dynamics matters, at least in two other dimensions. First, it is a broad conclusion on the BRI’s progress since 2013. Second, it can help to predict the future development of the BRI.

Before going into the structure of this dissertation, it is essential to specify two points. The BRI covers five continents and more than 100 countries. Hence, it is almost impossible to focus on every single member of the BRI for this paper. It focuses on the BRI members in South Asia, Central Asia, and Europe (including Russia) because these regions are core to the BRI. It is likely to be an afterthought that the Middle East and Africa were included in the BRI, following the logic of securing future energy supplies and relocating China’s labor-intensive industries [10]. South America and Oceania are far from the core, and this paper has no strong reason to focus on them. In addition, this paper focuses more on the developing countries that have failed to modernize from neoliberal globalization [11]. The BRI is more attractive to them because of their enormous infrastructure deficit [12]. When doing the literature research for this dissertation, the study focused more on the literature written close to 2023 to ensure the dissertation considers the latest information. This dissertation also includes the factors of the ongoing COVID pandemic and the Ukrainian War.

Part II of this dissertation assesses the BRI network effects and lock-in dynamics. It is divided into two sections. The first section is critical to this thesis. It is about the arguments that are positive for the BRI network effects and lock-in, which are based mainly on opinions from Bryan Druzin about network effects and lock-in: “network benefit and ‘thickness,’” “network size and ‘market share,’” “member status,” “coordination benefits,” “switching costs” and “spontaneous legal standardization [13] [14].” In addition, this section discusses two other points complementary to his arguments: resilience and cultural connectivity. Then, Part II considers the arguments against the BRI network effects and lock-in regarding sustainability, institutional flaws, fragmentism with Chinese characteristics, BRI’s neo-colonial elements, and cultural and ideological differences. Part III discusses the economic corridors as a case study. This part first clarifies the concepts of economic corridors and the link with network theory. It discusses the BRI’s economic corridors, focusing on the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

2. Overall Assessment of the BRI Network Effects and Lock-In

2.1 Positive Arguments

2.1.1 Network Benefit and ‘Thickness’: Infrastructure and Its Spill-Over Effects

Most actors join a network because of the benefits the network can bring. The importance of the benefit depends on the network's nature and purpose [15]. For a former Soviet republic, joining the European Union is more beneficial than joining the Commonwealth of Independent States. Apart from the primary benefit, the number of benefits also matters [16]. A network usually has spill-over benefits or “thickness” [17]. Usually, there is a positive link between network benefit and thickness and network effects and lock-in effect. A network driven by a “stick” is unlikely to be attractive, for example, Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Most BRI members are developing countries that are deficient in terms of infrastructure. In 20 or 30 years, more and more people in Asia will become urban inhabitants. Hence, the demand for urban infrastructure is high [18]. In 2020, the Asian Development Bank predicted that Asia’s infrastructure needs $ 730 billion annually [19]. Likewise, urbanization plays a vital role in the future development of Africa, and the demand for infrastructure construction is high. However, there is a widening investment gap between supply and demand in the Asian infrastructure market, and most developing countries in Asia have underinvested in infrastructure. Global economies, including the developed countries, have underinvested in infrastructure since the Global Financial Crisis, not just in Asia. In 2007, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development estimated that the global economy would need to invest around 3.5% of its GDP in infrastructure annually until 2030 to maintain economic growth and social development trends [20]. The global economic recession caused by COVID-19 and the Ukraine war will likely worsen the financial budget and the progress of infrastructure development.

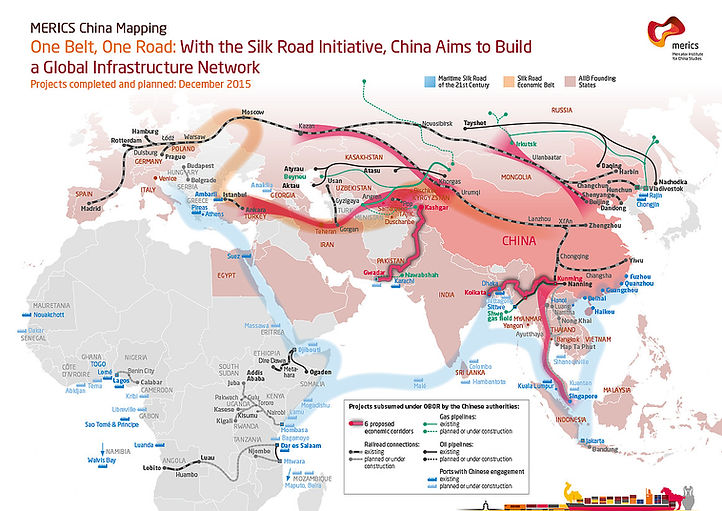

Figure 2: The Belt and Road Initiative creates a global infrastrcture network (Source: Mercator Institute for China Studies, 2015)

The most apparent benefit for BRI members is the infrastructure construction, and the BRI program may partially fill the infrastructure investment gap [21]. Interconnectivity of infrastructure development is the core of BRI as outlined by the Vision and Actions on Jointly Building the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road in 2015 [22]. The BRI calls for a multi-dimensional infrastructure network and upgrades land, seas, and air transportation routes by major railways, ports, and pipeline projects. China itself has rich experience in infrastructure construction. China has annual savings of nearly 50% of its GDP with a foreign exchange reserve of almost $ 5 trillion, which means China has the resources to finance the BRI project [23]. By January 2017, China announced over $ 900 billion in investments in more than 60 countries, including planned and ongoing investments. During the 2017 APEC CEO Summit, President Xi declared China’s next 15 years’ economic plan, including the $ 2 trillion investment outbound. For the BRI, China has also established a series of financial institutions. The most notable ones are the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the Silk Road Fund (SRF), and the New Development Bank (NDB), in addition to China’s policy banks and state-owned banks. Emerging economies initiated NDB and AIIB, sharing common objectives and interests, including providing financial resources for infrastructure building and sustained development projects in developing countries. Moreover, China has organized some intergovernmental investments, such as the China ASEAN Fund (CAF), the China Eurasia Cooperation Fund, and the China-Africa Development Fund [24].

However, there are no accurate estimations about China's investments in the BRI program due to a lack of transparency. The range is between $ 1 trillion and $ 8 trillion [25]. China is the primary financer of most of the BRI projects. By 2016, China’s export-import bank has allocated money to more than 2000 projects in 49 countries. China’s development bank is financing 400 projects related to the BRI in 48 countries [26]. By July 2018, China had invested 42 overseas ports in 34 countries. Also, the BRI has constructed railways and roads and an information and communication technology project. Viewed broadly, China is creating six economic corridors [27]. For example, China has pledged $60 billion to build power stations, major highways, new railways, and high-capacity ports for the CPEC [28]. The BRI’s infrastructure projects mainly concentrate on the developing world because two-thirds of the BRI funds are deployed to emerging and developing nations for infrastructural development. Over 7,000 project schemes are for infrastructure development projects focused on poverty alleviation, economic growth, and strategic collaboration [29].

Generally, the improvement of the quality of infrastructure has spillover effects. Primarily, infrastructure investments boost trade and economic growth. According to the World Bank, a 1% increase in infrastructure stock leads to a 1% increase in GDP [30]. In addition, better infrastructure quality is more attractive to foreign capital investments [31]. Returns on infrastructure investment are more visible in the early stages of emerging markets. For example, investments in transportation infrastructure played a positive role in China’s economic growth before the 2008 financial crisis [32]. Infrastructure improvement is also expected to facilitate the development of low-cost manufacturing hubs, accelerating the shift of low-cost, labor-intensive manufacturing from China to other developing countries. China has the problem of overcapacity production and rising labor costs, and the BRI members are new destinations for Chinese investment and business. In turn, these countries can provide the raw materials China needs. Thus, it will create job opportunities, diversify the economy, and increase export income. Poverty and inequality are significant issues for most developing countries because they perpetuate conflict and tension between and within nations [33]. Pakistan is a typical example of a poorly governed developing country [34]. The BRI is estimated to help 7.6 million people from extreme poverty and 32 million from moderate poverty [35].

Therefore, the BRI will likely produce powerful network effects and lock-in dynamics regarding network benefit and thickness.

2.1.2 Network Size and ‘Market Share’: 75% of the U.N. Members

Network size is essential for assessing the quality of network effects. Usually, the lock-in effect positively corresponds with the growth of users because the benefit increases with network size. To better understand the concept of network size, we need to know what “institutional market share” is [36]. “Institutional market share is the extent to which the number of states that could, in theory, participate in the organization as members of the institutional arrangement- that is, all the potential ‘consumers’ in the ‘institutional market’” [37]. There is also a positive link between institutional market share and the lock-in effect because an alternative network will be complex [38].

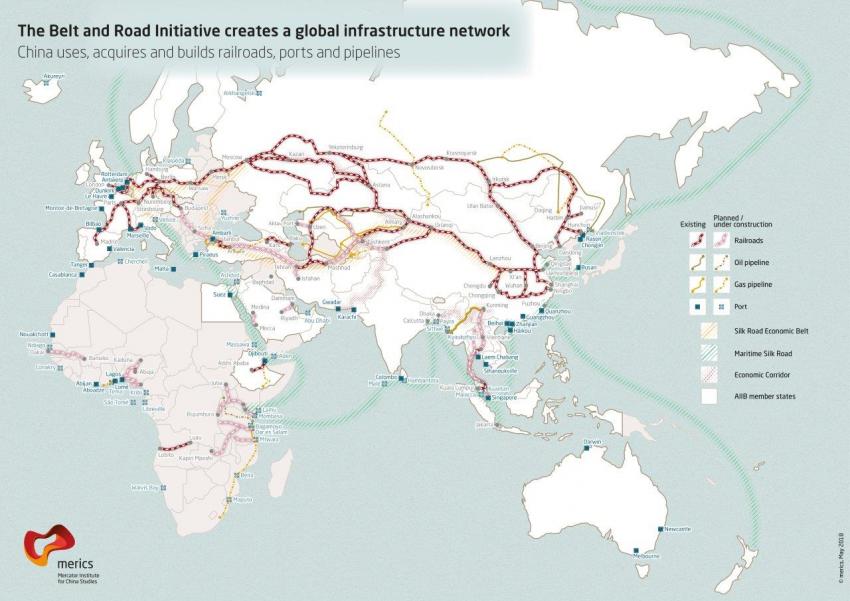

Figure 3: Countries of the Belt and Road Initiative (Source: Green and Development Center, 2023)

By December, around 150 countries have signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with China. Still, there are also a number of countries on the list that have not signed a full MoU [39]. The BRI has covered five continents. Most of the non-member countries are in North America and Western Europe. The United Nations has 193 member states. Hence, the BRI’s institutional market share is about 75%, meaning the BRI has included most counties worldwide. Therefore, another organization will unlikely replace the BRI unless “a massive exogenous shock” happens [40].

Hence, the BRI can generate strong network effects and lock-in dynamics regarding network size and market share.

2.1.3 Member Status: China, Russia, and the Developing World

Apart from size, the status of member states also has a positive connection with the network lock-in. Status refers to a country’s geopolitical and economic capacity and other factors, such as political stability. Also, the network's nature can determine a nation's corresponding status. A network with high-status members is more likely to produce a network lock-in for two reasons: the first is the value a high-status country can bring to the network.; secondly, a high-status country’s participation can shape perceptions about a network’s stability [41].

As mentioned, most BRI counties are developing counties, some are poorly governed, and their political stability is questionable. Nonetheless, their participation is essential for this project. For example, the CPEC is the ‘flagship project’ of the BRI [42]. Thus, Pakistan’s participation is decisive for the CPEC and vital to the whole BRI. Also, the BRI is China’s ideal of ‘new globalization’ [43]. Given this nature, it is logical that it is mainly attractive to developing countries aspiring for modernization after the disillusion of West-led globalization. Nevertheless, there are a few high-income economies in the BRI, such as South Korea, New Zealand, and Singapore [44]. The BRI includes two countries with significant economic and military clouts: China and Russia. As the strongest country, the US is not included in the BRI. However, this probably does not matter much for this project because Min Ye suggests that the BRI is China’s response to the US containment policy against China [45]. Therefore, China probably does not even expect the US’s participation in the BRI.

Hence, the BRI’s member status can produce powerful network effects and lock-in dynamics.

2.1.4 Coordination Benefits: Five Cooperation Priorities

“Synchronization value arises where agents require common standards to coordinate their interactions” [46]. For multi-dimensional institutions, the coordination of standards is usually not the primary benefit but an additional one. Organizations directly benefit from the standards coordination, which tends to produce a robust network lock-in effect [47].

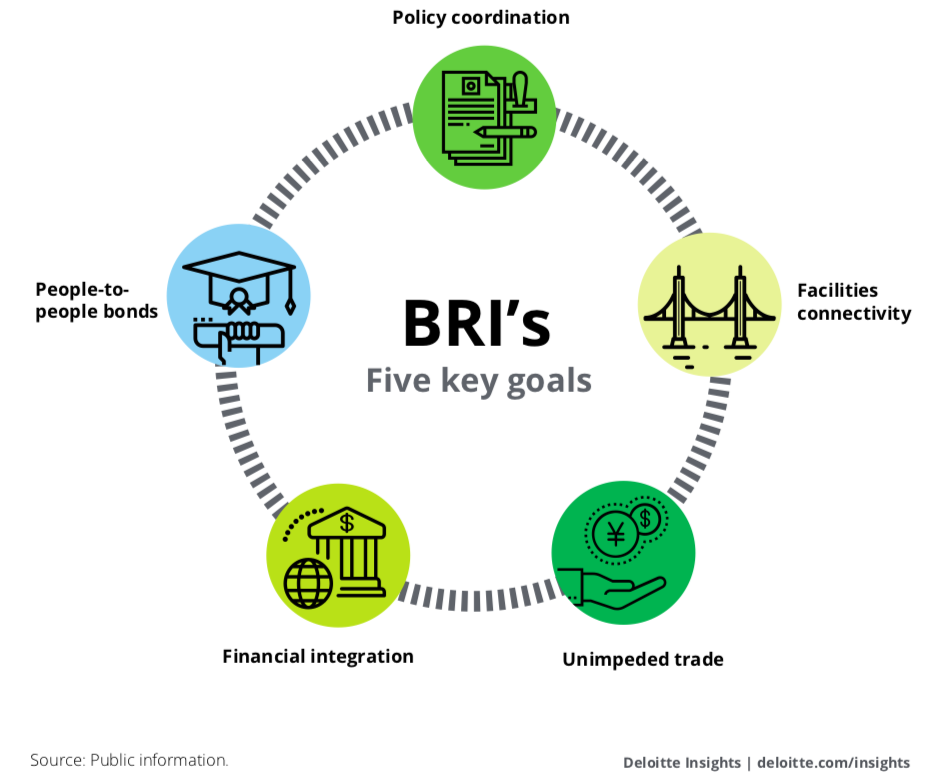

Figure 4: Policy coordination (Source: Public information)

By analyzing the BRI in Central Asia, Reeves finds that the BRI is a multi-dimensional coordination mechanism, not only in the material dimension, such as infrastructure, economy, and policy but also in the conceptual form, such as culture and education [48]. Liu and Dunford summarize the BRI’s five coordination priorities:

“By policy coordination, the initiative seeks to expand shared interests and establish a cooperation consensus with countries interested in the BRI, which is fundamental for co-developing large-scale cooperation projects. Through facilities connectivity, China proposes the development of infrastructure networks connecting sub-regions of Asia, Europe, and Africa and facilitating transport and logistics by removing institutional and technical bottlenecks. Developing several trunk land transport routes is an important part of facilities connectivity. Trade facilitation means the removal of investment and trade barriers and improved trade technologies (information exchange, inspection and supervision, customs clearance, and cross-border e-commerce) to develop a sound business environment jointly and expand mutual investment areas and technological cooperation. Financial cooperation aims to offer good-quality financial services and improve the efficiency and stability of financial systems. Symbolic projects in this area are AIIB, NDB, and the Silk Road Fund. People-to-people bonds mean increasing support and capacity for BRIs through cultural and academic exchanges, student exchanges, media, tourism and medical cooperation, joint research, cooperation between non-governmental organizations, etc.” [49]

This paper discusses examples of facility cooperation, trade cooperation, and financial cooperation in discussing the BRI network benefits and the BRI economic corridors. Thus, the following discussion concerns policy cooperation and gives examples of people-to-people connectivity.

Policy coordination is the core concept of the BRI, given the term used in the official document [50]. The BRI coordinates and synchronizes foreign policy initiatives with China’s domestic development [51]. Xi Jinping assured that the BRI ‘will build on the existing basis to help counties align their development strategies and form complementarities’ [52].

The policy cooperation between China and Russia is a good example to discuss because it is the foundation for successful cooperation between China and other BRI members, given the countries and regions involved. Russia’s notion of the Greater Eurasian Partnership complements the BRI as it seeks the coordination of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), ASEAN, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), and the BRI. This idea is practical because Russia already has a high degree of integration with other EAEU post-Soviet states and has established cooperation with ASEAN. From China’s perspective, the SCO can be a multilateral platform for maintaining regional security and facilitating economic development. In 2016, China and Russia signed a joint declaration outlining three principles of the Eurasian partnership. The following year, China and Russia signed another two joint declarations, which meant the transition from a “comprehensive Eurasian partnership” to the “Eurasian Economic Partnership” [53].

In Central Asia, China also uses the BRI as a framework to synchronize the policies. In 2015, China and Kazakhstan agreed to align Kazakhstan’s ‘Path of Light’ development strategy with the BRI to ensure a ‘win-win.’ In addition, China has coordinated security policies with the five Central Asian countries to count issues such as drug trafficking and the ‘three forces’ of terrorism, separatism, and radicalism [54].

Regarding people-to-people exchange, China has established some new think tanks, such as the Silk Road Think Tank Association or the 16+1 Think Tank Network, to promote the exchange of intellectual elites [55]. In addition, China has established the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) Scholarship in Central Asia to fund Central Asia students to study at Chinese universities [56].

Accordingly, the coordination benefits of the BRI can achieve strong network effects and lock-in dynamics.

2.1.5 Switching Costs: An Unprecedented Opportunity

If the costs of switching to a new network are significant, the network effectively locks the members inside even though they are always free to exit [57].

The BRI is not entirely free of other competing development visions. There are two notable examples of infrastructure construction projects- the G20 established the Global Infrastructure Hub, and Japan proposed the “Partnership for High-Quality Infrastructure.” Also, the Trump administration proposed the Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy that pursues free, fair, and reciprocal trade, which can be a countermeasure against the BRI [58]. However, as mentioned before, many BRI members failed to modernize under West-led neoliberal globalization. Hence, it is hard for them to have any remaining hopes or illusions. China is proposing an alternative, and China has sufficient financial capacity. The BRI might be able to break the West’s monopoly on the international economy and promote a right of development to these latecomers [59]. At least, it is an unprecedented opportunity for them.

Consequently, the BRI can engender substantial network effects and dynamics in switching costs.

2.1.6 Resilience: COVID-19 and the Ukrainian War

In addition to the arguments from Druzin, this paper argues that resilience is positively connected with network pressure and lock-in. Most countries prefer organizations that can adapt to the new normalities and weather the shocks. For example, after the Cold War, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) became a security organization [60]. Otherwise, NATO would not need to exist, given its original purpose to contain the Soviet Union.

The crisis after 2020 has demonstrated the strong resilience and adaptivity of the BRI. COVID-19 has posed severe challenges to the BRI. On the one hand, the lockdown caused the BRI-associated infrastructure and projects varying degrees of delays and cancellations; the economic repercussions caused by COVID-19 limited China’s ability to finance projects outside; in addition, the pandemic worsened the China-US rivalry and rendered negative public opinions against China including in the BRI members, but the anti-China sentiment in the BRI members is still manageable. On the other hand, the demand for medical equipment, e-commerce, technology, and logistics rose. Accordingly, China adjusted the BRI projects to soft institution-building with the BRI countries. In addition, China used COVID-19 to accelerate the soft institutions and collaborations in science and education that had already begun before COVID-19. For example, China’s scientific communities renewed and expanded cooperation with their BRI counterparts. Also, the AIIB pledged to finance member countries’ health infrastructure development and capacity building by using its $ 10 billion COVID-19 emergency fund. In 2020, Beijing affirmed the goal of constructing high-quality BRI infrastructure, focusing on the free-trade zone, the establishment of a Health Silk Road and a Digital Silk Road, and soft and social cooperation. Hence, the BRI scientific and soft institutions will likely grow in the post-COVID world. Moreover, given the escalating China-US rivalry, China has no reason to pause the BRI project [61].

In the context of the Ukrainian war, the BRI also shows its adaptivity and resilience. The overland connectivity between China and the EU has been impacted because of the physical inability to transit goods through Ukrainian territory, the financial inability to cross goods through Russian and Belarusian territory given the sanctions, and the practical or moral decisions to cease traveling goods through Russia and Belarus due to concerns associated with the war. Even though Ukraine merely accounted for 2% of westbound rail freight trade in 2021, the war has seriously impacted the New Eurasian Land Bridge (NELB), an overland railway and logistics network between China and the EU through Kazakhstan, Russia, and Belarus. By March 2022, freight traffic along the NELB had contracted by over 40% since February 24th. In response, the provincial Chinese authorities subsidize the routes with “war insurance” in case of unexpected things. More importantly, China has diverted to other alternative ways. For example, popular direct services from China to Hungry go either north through Poland or south via the Black Sea Ports at Constanta, Romania, and Varna, Bulgaria. To better stabilize the NELB, China can use the Southern Corridor that passes across the Caspian Sea by boat from the Kazakh Port of Aktau to Azerbaijan and then into the EU through Turkey or the Black Sea. This Corridor starts from Xi’an. Before the war, the Middle Corridor had become more popular, with- a 52% increase in cargo in 2021 [62]. Moreover, the War led Beijing to move fast with infrastructure projects in Central and West Asia, which were delayed because of the Kremlin’s reluctance. In 2023, the first China-Central Asia Summit was held in Xi’an. Beijing took advantage of Russia’s declining influence in Central Asia to deepen its ties with all five Central Asian countries [63].

Thus, the BRI can breed stable network effects and lock-in dynamics regarding resilience and adaptivity.

2.1.7 Cultural Connectivity: Harmony in Diversity

In international politics, there is “hard power,” such as economic and military clouts, and “soft power,” such as culture and ideology. Similarly, apart from considering soft power behind the network effects and lock-in dynamics, this dissertation argues that soft power is always behind them. Since its inception in the 1950s, the EU has always had a soft factor to yield network effects and lock-in: Europeans’ shared history and culture. The tributary system of Imperial China is also a good example. The core tributary states, Korea, and Vietnam remained loyal to this system partly because of their shared Confucianism with China [64].

Cultural proximity is often an underestimated factor when discussing the BRI. However, Kang et al. conclude that China assesses the BRI countries based on their characteristics: “such as natural resources, market size, infrastructure, institutional distance, and culture proximity which cultural proximity and market size were essential for inclusion into the initiative [65].” The BRI members’ political and business institutions, labor resources, and economic structure were not as important as expected in the selection process. Kang et al. also conclude that the BRI is not necessarily an infrastructure-led and institution-led project but is based on institutional cooperation and cultural convergence. According to their research, cultural proximity is even the most critical criterion in the BRI because it is the most crucial factor in attracting China’s outward foreign direct investment (OFDI): “Cultural distance of the host countries has a significantly negative effect on China’s OFDI” [66]. This dissertation does not argue if cultural proximity is the most critical factor in the BRI, but it should be cautious not to underestimate the cultural factor overtly.

Many people think most countries in the BRI have cultures distinct from China. This view is partially true. Kang et al. identify Chinese culture as “highly unequal, more collective, highly masculine, uncertainty tolerant, long-term oriented and very restricted [67].” Even though cultural distance exists between China and other BRI members, negative cultural distance is significantly lower among BRI members than among non-BRI countries. This is because the long history of cultural communication between China and these BRI members has alleviated the negative effect of cultural distance. The BRI continues a long tradition of economic, institutional, and cultural convergence with the BRI members instead of a temporary shock. Indeed, most BRI members are not even in the Confucianist cultural bloc, but Chinese Confucianist culture seeks “harmony in diversity” [68]. The friendship and infrastructure cooperation between China and Africa began much earlier than the launch of the BRI. For example, China constructed the TAZARA railway linking Tanzania and Zambia in the 1970s [69]. Many South Asian countries, such as Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia, are not Confucian but share many common Asian values with China. Many post-Communism countries are BRI members, such as Russia, former Soviet republics, and East Europe. China shares a ‘Silk Road Spirit’ with Central Asian countries based on the shared cultural and ethnic linkages from the (imagined) community of Silk Road traders, artists, and peoples [70]. Most developing countries in the BRI share the early modern history of colonial and imperial threats with China and aspire to development and prosperity.

Hence, people-to-people connectivity has a very positive impact on BRI network effects and lock-in dynamics.

2.1.8 Spontaneous Standardization with Chinese Characteristics

Spontaneous legal standardization “describes how unified legal standards may gain ascendancy across vast networks of actors without the need for central direction” [71]. The lex mercatoria is a typical example of spontaneous legal standardization. Spontaneous standardization is essentially the result of network effects. Guided by their rational consideration of network benefits, the actors move to a universal standard without a central authority to coordinate [72].

In many respects, the BRI is a spontaneous standardization with Chinese characteristics. Vangeli views the BRI as “a medium of the diffusion of normative principles that serve as the ground for developing novel governance, policy, and legislative thinking and practice outside of the hegemonic liberal democratic blueprint” [73]. Diffusion itself is “a mode of governance, policy, and legislation coordination” [74]. The BRI is an exemplary manifestation of the diffusion process. Though China the BRI’s center and coordinator, Beijing can only provide general guidelines, and the members make concrete policies according to their particular circumstances. This also reflects the asymmetrical structure of the BRI. Given its clout, China is a primary supplier of normative principles, but the demand side drives the process at least equally by “misrecognition and bounded rationality” [75]. Hence, the BRI is a voluntary process. The BRI’s voluntariness is more remarkable because there is no conditionality to be a BRI member, compared with many networks implementing “stick and carrot” to lure the actors to join and trap them inside. Nevertheless, given their bounded rationality, this process will eventually move into policy adjustment and interests’ congruence [76]. The BRI’s five coordination priorities, particularly policy coordination, have proven this voluntary process, as discussed above.

As a deduction, the voluntary policy standardization of the BRI manifests the BRI’s network effects and lock-in.

2.2 Negative Arguments

2.2.1 Sustainability

This dissertation argues that sustainability is directly linked to network effects and lock-in. Most actors prefer a network that can benefit them in the long term. Short-term benefits are not necessarily unattractive to actors, but most actors are more willing to join and stay in a network that can benefit them now and in the future. Even if an unsustainable network manages to trap the actors inside, this lock-in dynamics does not have much significance because the network is doomed to collapse.

Indeed, the BRI’s sustainability is a significant challenge for the BRI’s network effects and lock-in dynamic as the BRI “passes through volatile countries suffering from unstable government, brittle authoritarian regimes, unstable economies, terrorism, ethnic conflict, and other security threats and geopolitical risks” [77].

2.2.1.1 Economic and Financial Sustainability

Economic and financial sustainability are primary concerns. Infrastructure projects face challenges associated with low returns and high risk because the members of BRI projects received speculative grades from “B” to “BBB” regarding potential credit risk and market risk. In 2019, only 58.8% of the BRI countries with credit ratings reached a “BBB” or above rating, and some did not have credit ratings [78].

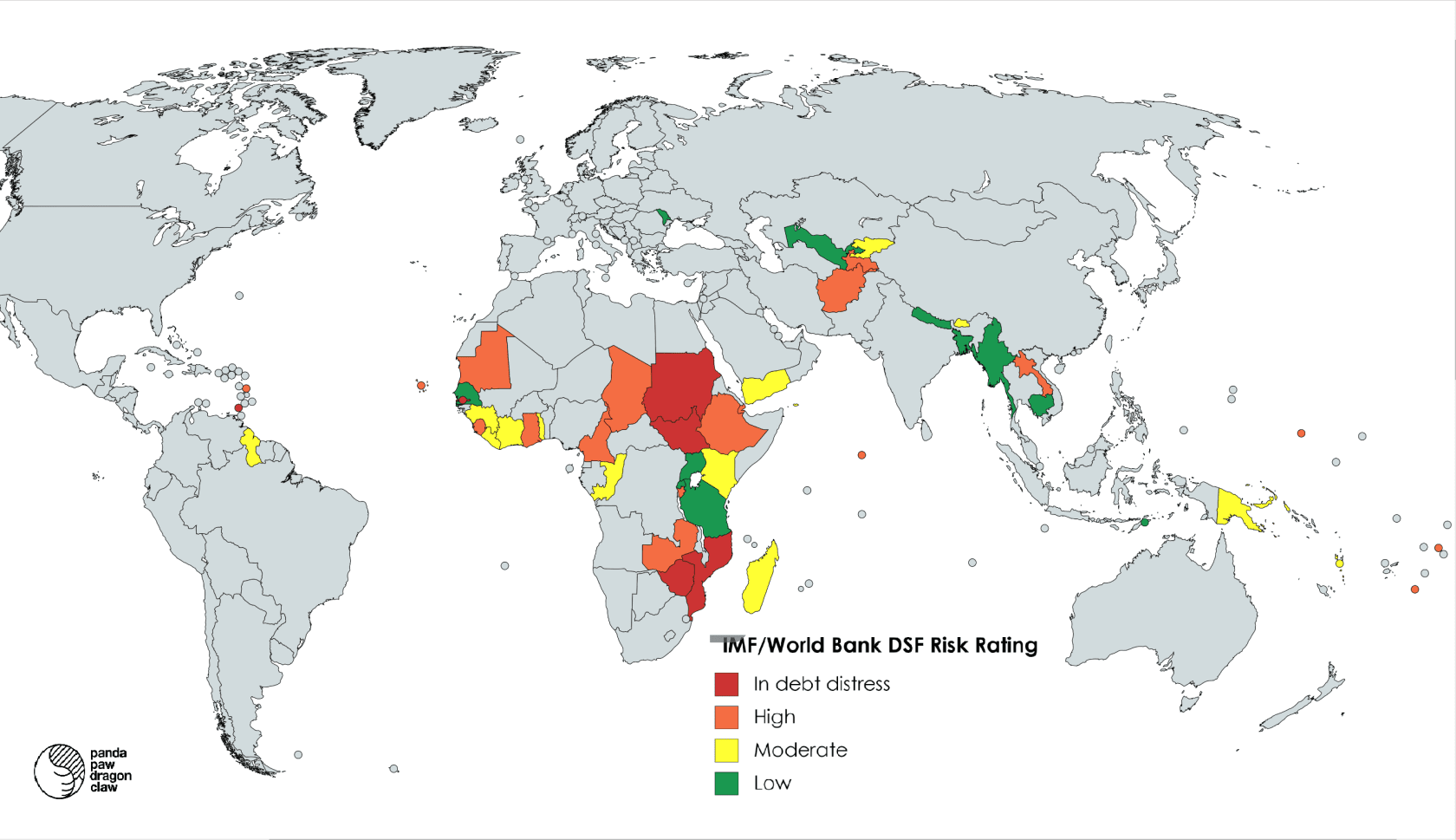

Debt sustainability challenges many BRI loan recipients because Chinese lending and loans may make some BRI members suffer from heavy debt and financial risks [79] [80]. For instance, the Export-Import Bank of China held 49% and 36% of Kyrgyz's and Tajik's government debt, respectively, in 2016 [81]. The Centre for Global Development in March 2018 found that 23 countries had the risk of debt distress because of BRI lending, and Djibouti, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, the Maldives, Mongolia, Pakistan, and Montenegro were vulnerable to debt distress because of future BRI-related financing. The high rates on Chinese loans or white elephant projects worsen the debt traps because they generate insufficient income to pay back debt, such as the Sri Lankan Hambantota Port [82]. These mismanagements can result from a lack of competency among Chinese lending institutions that care more about broader political goals than low potential returns and weak project planning capacity [83].

Figure 5: IMF/World Bank DSF Risk Rating (Source: Panda Paw Dragon Claw, 2019)

Even when an infrastructure project is finished, operation and maintenance costs account for half of the expenditure. In developing countries, inadequate management and maintenance can deteriorate railways, bridges, highways, and other infrastructure [84]. Given the complex investment environment, the BRI project in Latin America also faces many similar problems [85].

In response, China announced a Belt and Road Debt Sustainability Framework before the 2019 BRIC. For China, the massive projects coupled with low returns can create ‘the risk of strategic overdraft’ [86].

2.2.1.2 Socio-environmental Sustainability

Socio-environmental sustainability is another widely discussed threat to the BRI network. It mainly relates to the issues of labor and environmental degradation.

In January 2018, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) suggested that among 34 countries, 89% of contractors in Chinese-funded BRI transport projects were Chinese. Some studies show that the share of host countries in Chinese-funded BRI projects is overly low, ranging from 40% to 20% [87].

Since late 2017, adverse environmental effects have disrupted many BRI projects [88]. According to Khan et al., financial development, economic growth, and energy consumption increase carbon dioxide emissions and degrade ecological quality [89]. Hence, the BRI infrastructure and its spillover effects will inevitably pressure ecological sustainability. In November 2017, a few countries, including Pakistan, Nepal, and Myanmar, canceled a few hydropower projects with Chinese companies. In 2018, Myanmar canceled the $ 3.6 billion Myitsone Dam due to environmental issues and uneven disbursement of electricity [90].

Responding to environmental concerns, China has made significant progress in promoting eco-friendly infrastructure construction, green trade, green investment, green financing, and sustainable modes of production and consumption. In 2017, China launched the ‘Greening Belt and Road’ project to facilitate BRI’s green development. China has established a platform on the ‘Green Belt and Road Initiative Center’ to focus on green finance and sustainability. China also increased green collaboration with BRI members, for example, the Sino-Singaporean Tianjin Eco-City project in North China and the green innovation project in Shenzhen. However, the nexus between the BRI and sustainable development remains unclear because the green development alignments between China and other BRI members have significant gaps and potential [91].

2.2.1.3 Political Sustainability

Political sustainability is another disruption to the BRI. Khan et al. conclude that political stability, government effectiveness, and corruption positively relate to environmental quality. Political risks include political stability, government effectiveness, and corruption [92]. Unlike the Western countries, China resists interfering with other countries’ domestic affairs. However, this is not necessarily good for the BRI. China may have to comprise its non-interventionist approach [93].

Many BRI members pose significant political risks. Infrastructure investments in BRI members with substantial political risks are vulnerable to nationalization, expropriation, and other takings. In a host country with weak investor protection regimes, confiscation and seizure of funds occur frequently. Infrastructure investments are also vulnerable to geopolitical events such as political instability, conflicts, and terrorism [94]. The political instability in Pakistan and Kazakhstan in 2022 is a recent example. Political instability either directly or indirectly affects foreign direct investments (FDI). However, the BRI is not backed by an investment insurance facility to decrease political risks in developing countries. The Myitsone Dam project in Myanmar well manifests how political risks affect infrastructure investments [95]. Political risks in those countries also harm environmental quality [96].

2.2.2 Institutional Flaws

Institutional flaws can directly or indirectly damage network effects and lock-in. An organization with institutional deficiencies can still produce network effects and lock-in, but the institutional weaknesses always curtail the impact of network effects and lock-in.

Institutional flaws of the BRI are primarily about corruption or transparency and the rule of law.

Despite China’s efforts in the past ten years, there is much space for progress. Transparency International states China is ranked 65th among 180 countries in the corruption perceptions index [97]. In the latest report from the World Justice Project, China is ranked 97th in 139 countries and jurisdictions regarding the rule of law index [98]. Many BRI countries are even worse and deficient regarding the rule of law and corruption. For example, many BRI countries, e.g., the Philippines and Malaysia, are vulnerable to bribery and embezzlement [99]. The standard behind these indexes might be too Western-centric. Nevertheless, the institutional deficiencies are apparent in the BRI.

The corruption and the questionable rule of law in the BRI are very detrimental to its development. As the foundation of the BRI, infrastructure projects are particularly susceptible to corruption. Along the BRI, some significant cases concerning transnational bribery and transnational corruption, including the 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) scandal, the Patrick Ho Chi-Ping case, and the BTA Bank case, have revealed institutional flaws. Also, the enforcement of arbitration may be a problem, considering the need for the rule of law in some BRI countries. This institutional flaw is severe because arbitrating conflicting interests between countries is vital to an organization like the BRI. It remains to be seen whether China and other BRI members can develop an institution like the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) [100].

2.2.3 Fragmentism with Chinese Characteristics

As mentioned above, Vangeli thinks the BRI is a voluntary process with China as the center providing general guidelines and other members making concrete policies according to their circumstances. The BRI inside China parallels the BRI outside China, as argued by Min Ye. However, she holds a different opinion regarding the repercussions of this model on the BRI.

Min Ye thinks the voluntary process is “bureaucratic fragmentation.” The ruling elites use the strategy of “ambition and ambiguity.” “Ambition” functions as a nationalist ideology to overcome fragmentation, and “ambiguity” allows different interest groups to interpret and implement the strategy according to their needs. Therefore, implementation is a process of “interpretation and improvisation” [101].

Min Ye believes this fragmentism is dangerous to the BRI outside China. The Chinese “political industrial complex” is deeply commercial-oriented, and prioritizing internal growth continues to shape Chinese outward investment and lending. This means the Chinese BRI implementers are likely to prioritize Chinese commercial interests. The problem is that the recipient countries may be misled by the rhetoric of the Chinese state, such as “win-win” and “community of common destiny,” as these “ambitions” seem to care less about profits and returns. Hence, the gap between Chinese actions and recipient expectations will cause diplomatic friction between China and BRI recipients [102]. Zhao also believes that mobilizing all segments of the Chinese bureaucracy and state-owned and private companies has resulted in a fragmented and patchy initiative where superficial enthusiasm does not match solid coordination. Zhao also points out that the absence of a clear definition of the BRI has given rise to a situation where every investment project with Chinese involvement claims to be in the framework of the BRI [103].

Thus, this fragmentism with Chinese characteristics can detrimentally impact the BRI’s network effects and lock-in dynamics.

2.2.4 An Imperialism-Style Capital Accumulation?

Despite China’s rhetoric about the BRI, some still criticize the BRI as neo-colonialism or neo-imperialism. It is hard to say that an imperial-style network can be too appealing.

Like some other critics of BRI, Merwe thinks that the BRI is an outward expansion of China’s internal mode of capital accumulation. The BRI is inter-imperialist or sub-imperialist because of the organic capital accumulation through manufacturing, industrial complexes, various spatial development initiatives, and the subsequent uneven development within the chosen spatio-temporal fix. Merwe discusses the BRI in the Middle East and Africa. Because of the rich resources and low labor costs in the Middle East and Africa, China can export its labor-intensive manufacturing and obtain the resources China demands. The weak government in these two regions is vulnerable to resisting the power of Chinese capital and manufacturing. By hosting the labor-intensive manufacturing from China, it is hard to conclude that the Middle East and Africa will move to a higher position in the global value chain. It is even questionable whether this manufacturing relocation can create meaningful job opportunities for the host countries [104].

This accusation of BRI can undoubtedly damage the BRI network’s reputation and thus disrupt BRI’s network effects and lock-in dynamics.

2.2.5 Cultural and Ideological Differences

Despite the relative cultural proximity between China and BRI countries, we cannot ignore their apparent cultural and ideological differences.

When Chinese companies develop offshore projects, the Chinese employees and host countries’ employees inevitably face cultural tensions. The differences in attitude towards work, understanding of religious duties, networking and relationship development, communication, and even food options can all lead to inferior work performance [105]. As China goes out, ideological conflicts always exist. Despite the underdevelopment, many BRI members are relatively more liberal than China. Hence, China must face the issue of transparency, the opposition voices from the local civil society, the media, and the opposition parties, which China does not need to worry about too much inside [106]. The attitude that Chinese companies often disregard local conditions to move projects despite solid local opposition can worsen the situation [107].

The cultural and ideological differences disturb the BRI network’s harmony by causing tensions between people. Thus, they are opposed to the effects of network and lock-in.

3. BRI Economic Corridors

3.1 What Is an Economic Corridor?

Wolf thinks “an EC is designed to create global, regional and domestic value and supply chains through the creation and connection of economic centers; ideally, it is to produce positive multi-sectoral spill-over effects [108].” Economic corridor is far beyond the infrastructure but a “comprehensive development approach” that produce economic, social, and political impacts [109].” Wolf made a comprehensive table that covers the key indicators and criteria of economic corridors, as shown in the table below [110].

Table 1: Key indicators and criteria of economic corridors

Key Indicators |

Characteristics (Criteria) |

|

01 |

Conceptualized geographical framework |

• ECs span different scales: • Broad scale: regions, sub-regions, and nations • Local scale: subordinated territorial entities • Geographical framework: naturally given or defined through planning |

02 |

Identified growth zones |

• Existence of centers of economic activities • Availability of resources |

03 |

Established Special Economic Zones (SEZs) |

• Usually, the existence of fully-fledged and functioning SEZs |

04 |

Internal connectivity |

• Connectivity within the Geographical Framework : • Connectivity between the grow zones; • Connectivity within grow zone; • High level of intermodal connectivity |

05 |

External connectivity |

• Connectivity beyond the Geographical Framework • Connectivity between different ECs • Linking grow zones with nodes outside own geographical framework |

06 |

Articulated common culture and history |

• Awareness of a common cultural and historical ground • Use of ‘Soft Power’ instruments |

07 |

Processes of modernisation and industrialisation |

• Existence of ‘enabling industry’ • Improvement of existing industrial capacities • Restructuring of manufacturing • Creation of new industrial capacities |

08 |

Social and societal development |

1. General uplift in living standards 2. Improvement of social indicators 3. Increase in social integration 4. Bridging cultural and ethnic cleavages 5. Containment of ‘social evils’: terrorism, religious fundamentalism etc |

09 |

Effective and fair regional distribution mechanism |

1. Overall regulations of centre-region relations 2. Investment allocation 3. Income and revenue distribution 4. Distribution of financial costs |

10 |

Pre-existence of economic viability |

1. Natural propensity for economic growth and development 2. ‘Enabling economic mass’ encompassing a large amount of economic resources and actors 3. Pre-existent strong economic growth |

11 |

Integrated and comprehensive EC planning |

1. Overall EC vision 2. Concrete action plan |

12 |

Sufficient political will |

1. Existence of driving forces 2. Commitment and constructive mindset among all major actors 3. Existence of an encompassing consensus 4. Accommodation of local concerns and interests |

13 |

Enabling Policy Frameworks and mechanisms (‘soft infrastructure’) |

1. Financial mechanisms 2. Transparency and accountability programs and institutions 3. Supporting harmonised rules, regulations, and standards 4. Enabling ‘smart’ economic policy 5. Effective systems of domestic resource mobilisation |

14 |

Enabling institutional structures and mechanisms (‘hard infrastructure’) |

1. Institutional capacities 2. Abilities to reform 3. Human resources and management capacities |

15 |

Enabling and favourable (safe) environment |

1. Zoning security: Comprehensive security concept 2. Geographic stability: Good governance 3. Positive image |

16 |

Effective diplomacy |

1. Public diplomacy 2. Negotiation mechanism (regional, bilateral, multilateral) |

17 |

Sustainability, ecological and environmental aware |

1. Programs for ecological and environmental awareness and protection; 2. Triple-bottom line approach combining environmental, social and economic considerations |

18 |

Absence of crucial inhibitors (vetoactors and market distortion |

1. Healthy civil-military relations 2. Absence of MILBUS (Military in Business) 3. No economic monopoles and prerogatives of state-agencies |

Therefore, an economic corridor is undoubtedly a network. A well-established economic corridor-style network can produce potent network effects and lock-in dynamics as it covers almost all the factors directly or indirectly relevant to network effects and lock-in dynamics, if not more.

3.2 The BRI’s Economic Corridors

The BRI consists of two large-scale development proposals: the land-based ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ (SREB) and the sea-based ‘Twenty-first Century Maritime Silk Route Economic Belt’ (CMSR). Given that the land-based road encompasses 65% of the project and the sea-based road contains 35%, the SREB is the key [111]. In essence, three economic corridors make up the SREB.

“Firstly, the Northern Corridor connects China with Europe by land via Russia. Secondly, the Central Corridor focuses on infrastructure build-up between China and Europe via Iran and Turkey by both land and sea. Thirdly, the Southern Corridor, which is actually the CPEC, aims to connect Kashgar in China’s Xinjiang province with Pakistan’s sea ports in the South (particularly Gwadar). Being located at the intersection between Central, South, and East Asia, Xinjiang turns into a geographic lynchpin for the BRI’s connectivity as concerns the Eurasian landmass and the BRI’s maritime linkages. The latter is provided via Pakistan’s part of CPEC, which determines the essential link between land and sea connectivity” [112].

In addition, there are three other economic corridors, but they are still during the planning stage: the China-Mongolia-Russia corridor, the China-Myanmar-Bangladesh-India corridor, and the China-Southeast Asian mainland corridor [113].

Battamo et al. identify seven BRI economic corridors [114]. Through this maritime corridor, CPEC connects China to Europe via Africa and the Middle East [115]. These seven economic corridors include 132 countries, as shown in the table below [116].

Table 1: Seven economic corridors include 132 countries

BRI economic corridors |

Number of countries |

Name of the countries |

Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor (BIM) |

6 |

Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka |

China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor (CWA) |

23 |

Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Georgia, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kyrgyzstan, Lebanon, Moldova, Montenegro, Palestine, Romania, Serbia, Syria, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan |

China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor (ICP) |

19 |

Brunei, China, Fiji, Indonesia, Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, Micronesia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Republic of Korea, Singapore, Solomon Islands, Suriname, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Vanuatu, Vietnam |

China-Mongolia-Russian Economic Corridor (MRF) |

6 |

Belarus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Mongolia, Russia |

China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (PAK) |

9 |

Afghanistan, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Yemen |

New Eurasian Land Bridge Economic Corridor (ELB) |

12 |

Austria, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Kazakhstan, Luxembourg, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Ukraine |

21st-C Maritime Silk Road Economic Corridor (21C) |

57 |

Algeria, Angola, Benin, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Cote d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Libya, Madagascar, Maldives, Mali, Malta, Mauritania, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Western Sahara, Botswana, Central Africa Republic, Burkina Faso, Eritrea, Guinea-Bissau, Malawi, Mauritius, Republic of the Congo, Somaliland |

Therefore, the connectivity in the BRI network is through these economic corridors. Through the SREB-based economic corridors, China intends to build a connected and cohesive Eurasian entity, and China is the central force underlying connectivity. To achieve this, China is strengthening infrastructural connectivity, economic connectivity, and other connectivity in Eurasia. Regarding the other three envisaged economic corridors, China intends to interlink the Eurasian countries through infrastructural connectivity and national and regional development coordination. Combining these economic corridors, China aims to create an interconnected and cohesive Eurasian economy by connecting transportation networks and markets, dispersing, and improving Eurasia’s production capacity, and facilitating the transit of goods, capital, energy, raw materials, and even information, people, and cultures [117] [118].

Within the BRI economic corridors, some major hubs can potentially become multimodal transportation gateways (rail-air, air-maritime, maritime-rail, or rail-air-maritime) to improve the BRI network’s interconnectivity between economic corridors [119].

Behind the glaring appearance of the BRI economic corridors, serious risks are inherent. To test the BRI’s sustainability in terms of financial, ecological, and social dimensions, Battamo et al. used the methodology of resilience analysis to evaluate the Ecological Vulnerability (EV) and Adaptive Capacity (AC) of BRI river basins from 1990 to 2015 [120]. They made the following conclusion [121]:

1. Most of Africa, South Asia, Central Asia, and the Middle East have low resilience.

2. Africa shows the lowest resilience among the corridors mainly because of its low AC (deficient economy, governance, and human development)

3. The economic corridors of Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar, China-Indochina Peninsula, China-Pakistan, and China-Central Asia-West Asia have low resilience because of high EV and low AC.

4. Since 1990, there has been significant progress in large portions of the BRI economic corridors, particularly the China-Indochina Peninsula, due to the rise in AC.

5. Most BRI economic corridors deal with limited resources and ecological vulnerability. The growing population will worsen the current situation.

3.3 CPEC

CPEC eclipses all other economic corridors among the BRI economic corridors given its significance, and CPEC is also the most frequently discussed. CPEC is the “flagship project” or “pilot project” of the BRI [122]. Therefore, the analysis of CEPC can also apply similarly to other BRI economic corridors.

Figure 6: China’s ambitious plan for Pakistan (Source: Mercator Institute for China Studies, 2020)

3.3.1 Chinese Investments and Economic Benefits

The investments China makes in Pakistan are the most significant foreign direct investment (FDI) in Pakistan [123]. CPEC comprises 21 energy projects, eight infrastructure projects, the twelve projects of the Gwadar Port, four rail-based mass transit projects, and three ICT (Innovation and Communication Technology) projects [124]. By 2030, there will be more than $ 50 billion in investment plans. CPEC aims to add 17,000 megawatts of electricity at about $ 34 billion [125]. China plans to establish 24% of the power projects of the BRI in Pakistan [126]. The rest of the money will be used to build transport infrastructure, including the railway line between the port megacity of Karachi and the northwest city of Peshawar [127]. Kashgar in Xinjiang will connect with Gwadar port through a 3,000-kilometer network of roads and railways. Gwadar port has “game changer” significance as it provides a solution to the Malacca Dilemma China faces [128]. China is also establishing special economic zones to create better economic conditions for Chinese firms’ investments in Pakistan [129].

For a small country like Pakistan, these projects will benefit Pakistan enormously. Pakistan’s economy has suffered a law-and-order crisis, export stagnation, under-investment, chronic energy shortages, and flailing state institutions [130]. Nonetheless, Pakistan has considerable strength and potential [131]. Gwadar port can significantly affect Pakistan’s economy by transforming the CPEC network into a regional trading and transshipment hub in the Gulf and a strategic gateway for Middle Eastern oil shipments [132]. CPEC has helped Pakistan achieve the highest economic growth in eight years, according to the data in 2016 [133]. Pakistan’s Government expects CPEC to create 700,000 jobs from 2015 to 2030 and increase its economic growth to 2.5% [134]. The improved infrastructure will have spillover effects: attract more FDI, boost Pakistan’s economy, and alleviate Pakistan’s persistent power shortfalls and poverty [135][136]. Also, CPEC will link Baluchistan with Sindh Gilgit, and Baltistan. Baluchistan has rich mineral deposits, including the most significant untapped copper and gold reserves. In addition, CPEC is expected to help Pakistan increase large-scale coal production. China is keen to invest in the mining industry to increase thermal power production by up to 13,000 megawatts annually [137].

CPEC’s spillover also has emerged outside this network. As early as 2015, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the UK announced their funding schemes for CPEC. Central Asian countries, Turkey, Iran, Russia, the UK, and France, have also expressed interest in joining the CPEC network [138].

3.3.2 Challenges Towards CEPC

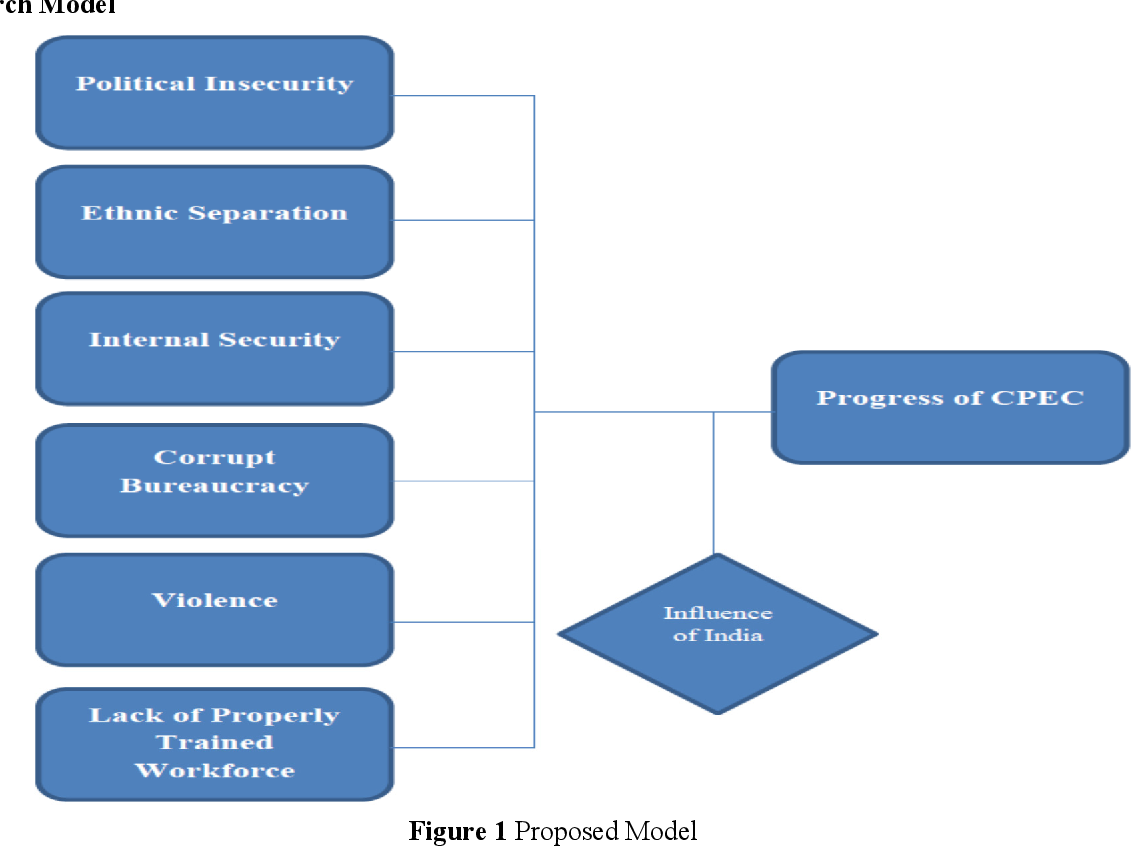

Yet, like some BRI members, Pakistan’s social-ecological, economic, and political situations are fragile, and cultural and ideological gaps are not negligible. These challenge the implementation of CPEC.

Figure 7: Proposed Model (Source: Analyzing Prevalent Internal Challenges to China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) through Public Opinion, Sultan Muhammad Faisal, 2019)

CPEC could worsen Pakistan’s economic and financial vulnerability, which is already heavily indebted. Pakistan’s Federal Minister for Ports and Shipping, Mir Hasil Bizanjo, disclosed that the Gwadar Port agreement requires Pakistan to pay back $ 16 billion of loans from Chinese banks at more than 13% (including 7% insurance charges). This deal might be a heavy debt burden and undermine Pakistan’s national interests. Also, the costs of upgrading and maintenance of infrastructure facilities would be substantial [139].

The legal-constitutional challenge in Gilgit-Baltistan is destructive to CPEC. Gilgit-Baltistan is the only land connection between China and Pakistan; with it, it is possible to implement CPEC. China has invested a lot in the Gilgit-Baltistan region's roads, pipelines, and communication networks. Gilgit-Baltistan also has enormous geostrategic relevance because it connects China’s Xinjiang and Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor with other essential areas of Pakistan and India. However, Gilgit-Baltistan is at the center of disputed territories between India and Pakistan. This could increase political resistance against Beijing’s investments and discourage non-Chinese economic engagements [140].

In terms of security and law and order dimensions, CPEC faces religious extremism, radicalization, sectarian and ethnopolitical violence, and other severe issues. The situation has been worsening in recent years. The worse is that Chinese workers and companies are increasingly targeted, and anti-Chinese agitation and violence are rising in Pakistan [141]. More specifically, the security challenges come from four aspects: “(1) the Baluchistan factor; (2) the Uyghur issue; (3) domestic terrorism, militancy, and ungoverned territories; and (4) international jihadism” [142]. Among these, the Baluchistan factor directly threatens the Gwadar port with enormous natural resources and geostrategic value. The Uyghur issue is linked with the Uyghur nationalism in Xinjiang and the global jihadist movement [143].

The political, institutional, and administrative challenges are also severe. These are related to bad governance, inefficient bureaucracy, and corruption in Pakistan. All sorts of domestic problems, from political discontent and religious radicalism to unhealthy civil-military relations, can be traced back to Pakistan’s low quality of governance [144]. Moreover, CPEC can reinforce rampant corruption and nepotism [145]. In particular, the ‘Militablisment’ of the Pakistan state and the conflict between military leadership and civilian government threaten the implementation of CEPC [146].

The unfavorable environmental conditions are detrimental to the implementation of CPEC. Large parts of CPEC’s geographic framework are prone to natural and human-induced disasters. Severe natural incidents have already destroyed substantial portions of the designated CPEC infrastructure [147].

Even though Islamabad and Beijing refer to their relationship as ‘all-weather friends,’ the existing cultural and ideological differences are not negligible. The Pakistan Government is democratically elected, and the Government is required to reveal the details of deals signed with China. However, the Government keeps the true nature of CPEC funding, terms and conditions attached beyond public scrutiny. Some major state institutions and media have criticized this opacity. Some signs suggest Pakistan’s central Government is trying to control the spread of negative news about CPEC. However, as a nascent democracy, freedom of opinion is essential [148]. Cultural distance between peoples of the two sides is also opposed to the efficient implementation of CPEC. Most Pakistani employees are troubled by the Chinese employees’ limited knowledge of the Muslim culture. Pakistani and Chinese employees have distinguishing attributes regarding basic cultural and religious norms and English proficiency. Although the employees from both sides make certain adjustments during the project, the cross-cultural adjustment is insufficient due to misunderstandings, language barriers, and cultural norms differences [149].

4. Conclusion

This paper first analyzes the positive arguments for the BRI to produce strong network effects and lock-in dynamics. The BRI’s infrastructure element is the primary pro-argument of its network effects and lock-in dynamics. The massive infrastructure projects and the spill-over results are attractive, especially to developing countries. The BRI’s member number and member status suggest the strong trend of the BRI’s network effects and lock-in dynamics. The BRI’s five cooperation priorities, the policy coordination in particular, support the coordination benefits of the BRI. Regarding switching costs, the BRI is an unprecedented opportunity for many members as there does not seem to be another grand project like the BRI, and no other country has the resources to organize such a great project. In addition, this paper reinforces the argument of the BRI’s network effects and lock-in dynamics by discussing the BRI’s resilience throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ukrainian war, and the relative cultural proximity between the BRI members. The last argument of the BRI’s spontaneous coordination directly manifests the network effects the BRI is producing.

Then, this paper considers the challenges to the BRI’s network effects and lock-in dynamics. The biggest challenge to BRI’s network effects and lock-in dynamics is the sustainability from economic, socio-ecological, and political dimensions, considering many BRI members are not well-governed countries. The institutional flaws are also damaging to the BRI network. The argument of fragmentism with Chinese characteristics is also worth noting about the BRI network’s coordination and harmony. The critics of BRI’s imperialist nature can make the BRI members and non-BRI countries more hesitant and cautious about implementing the BRI. Lastly, the apparent cultural and ideological gaps have adverse impacts on the BRI network that cannot be ignored.

Finally, this paper explores the BRI economic corridors, focusing on CPEC as a case study regarding the primary pro-argument and the primary counterargument of BRI’s network effects and lock-in dynamics. If the BRI is a network, each BRI economic corridor is a sub-network of the whole. China uses these economic corridors to build an inter-connected Eurasian entity. However, a large portion of the economic corridors face sustainability problems from economic, social, and ecological dimensions. Pakistan is a typical example of a poorly governed country; its vulnerable social, political, and economic conditions can seriously undermine the efficient implementation of CPEC.

China is building a material foundation for the BRI network primarily through infrastructure and the spill-over effects and a conceptual foundation through people-to-people exchange and other soft ways. At this stage, the Belt and Road Initiative and China’s growing global interconnectivity are generally generating network effects and lock-in dynamics. This also explains why so many nations decided to join it despite the U.S. spread of BRI-related “China Threat” discourse. Most member nations view BRI primarily as an opportunity when fewer alternatives exist [150]. The construction of infrastructures is reconfiguring (inter)dependencies between China and BRI countries, affecting regional power dynamics, and contesting existing regional/global orders, potentially ushering in a Sino-centric era of global economic activity [151].

However, the extent of network effects and lock-in dynamics are not significant, considering that the challenges from various aspects undermine them in a nonnegligible way. This paper does not explore other risks; for instance, the pandemic has led to deep skepticism about relying too closely on China’s BRI plans [152]. Suppose China and other BRI members do not take more action to overcome these challenges effectively. In that case, the degree of network effects and lock-in dynamics will gradually decline and even lose, as these challenges’ undermining force will become more discernible as time elapses.

References

[1]. Siddiqui, K. (2019). One Belt and One Road, China’s massive infrastructure project to boost trade and economy: an overview. International Critical Thought, 9(2), p. 224, 214-235. https://doi.org/10.1080/21598282.2019.1613921

[2]. Xing, L. (2018). China’s Pursuit of the “One Belt One Road” Initiative: A New World Order with Chinese Characteristics? In Xing, L. (Ed.). Mapping China’s “One belt one road” initiative (pp. 1-27). Palgrave Macmillan. https://link-springer-com.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/book/10.1007/978-3-319-92201-0

[3]. Chung, C. P. (2018). What are the strategic and economic implications for South Asia of China’s Maritime Silk Road initiative?. The Pacific Review, 31(3), p. 7, 315-332. https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2017.1375000

[4]. Merwe, J. V. D. (2018). The One Belt One Road Initiative: Reintegrating Africa and the Middle East into China’s System of Accumulation. In Xing, L. (Ed.). Mapping China’s “One belt one road” initiative (p. 200, pp. 197-217). Palgrave Macmillan. https://link-springer-com.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/book/10.1007/978-3-319-92201-0

[5]. Xing, L. (2018). China’s Pursuit of the “One Belt One Road” Initiative: A New World Order with Chinese Characteristics? In Xing, L. (Ed.). Mapping China’s “One belt one road” initiative (pp. 1-27). Palgrave Macmillan. https://link-springer-com.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/book/10.1007/978-3-319-92201-0

[6]. Battamo, A. Y., Varis, O., Sun, P., Yang, Y., Oba, B. T., & Zhao, L. (2021). Mapping socio-ecological resilience along the seven economic corridors of the Belt and Road Initiative. Journal of Cleaner Production, 309, 127341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127341

[7]. Flint, C., & Zhu, C. (2019). The geopolitics of connectivity, cooperation, and hegemonic competition: The Belt and Road Initiative. Geoforum, 99, 95-101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.12.008

[8]. Druzin, B. H. (2020). Can the Liberal Order be Sustained? Nations, Network Effects, and the Erosion of Global Institutions. Mich. J. Int’l L., 42, 1. https://web-p-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=0&sid=e0a7bc3b-23df-4ab1-a81b-88c43215e151%40redis

[9]. Vangeli, A. (2018). A Framework for the Study of the One Belt One Road Initiative as a Medium of Principle Diffusion. In Xing, L. (Ed.). Mapping China’s “One belt one road” initiative (pp. 57-89). Palgrave Macmillan. https://link-springer-com.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/book/10.1007/978-3-319-92201-0

[10]. Zhao, S. (2020). China’s Belt-Road Initiative as the signature of President Xi Jinping diplomacy: Easier said than done. Journal of Contemporary China, 29(123), 319-335. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2019.1645483

[11]. Druzin, B. (2017). Towards a Theory of Spontaneous Legal Standardization. Journal of International Dispute Settlement, 8(3), 403-431. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnlids/idw023

[12]. Sheng, J. (2020). The ‘One Belt, One Road’ Initiative as Regional Public Good: Opportunities and Risks. Or. Rev. Int’l L., 21, 75. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/porril21&div=5&id=&page=

[13]. ] Lisinge, R. T. (2020). The Belt and Road Initiative and Africa’s regional infrastructure development: implications and lessons. Transnational Corporations Review, 12(4), 425-438. https://doi.org/10.1080/19186444.2020.1795527

[14]. Cheshmehzangi, A., Xie, L., & Tan-Mullins, M. (2021). Pioneering a Green Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) alignment between China and other members: mapping BRI’s sustainability plan. Blue-Green Systems, 3(1), 49-61. https://doi.org/10.2166/bgs.2021.020

[15]. Wolf, S. (2020). The China-Pakistan economic corridor of the belt and road initiative: Concept, context and assessment (Contemporary South Asian studies). https://link-springer-com.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/book/10.1007/978-3-030-16198-9

[16]. About the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). (2023). Green Finance & Development Center https://greenfdc.org/belt-and-road-initiative-about/?cookie-state-change=1703868593720

[17]. Shah, A. R. (2018). How Does China–Pakistan Economic Corridor Show the Limitations of China’s ‘One Belt One Road’ Model. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 5(2), 378-385. https://doi.org/10.1002/app5.224

[18]. Ye, M. (2020). The Belt Road and beyond: state-mobilized globalization in China: 1998–2018. Cambridge University Press. https://books.google.co.nz/books?hl=en&lr=&id=2tLKDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR8&dq=The+Belt+Road+and+beyond:+state-mobilized+globalization+in+China:+1998%E2%80%932018.+&ots=k72QnuUf3O&sig=OvSBX_ram2EnRHrsxJoUmn0-rVU#v=onepage&q=The%20Belt%20Road%20and%20beyond%3A%20state-mobilized%20globalization%20in%20China%3A%201998%E2%80%932018.&f=false

[19]. Reeves, J. (2018). China’s silk road economic belt initiative: Network and influence formation in Central Asia. Journal of Contemporary China, 27(112), 502-518. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2018.1433480

[20]. Liu, W., & Dunford, M. (2016). Inclusive globalization: Unpacking China’s belt and road initiative. Area Development and Policy, 1(3), 323-340. https://doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2016.1232598

[21]. Li, Y. (2018). The greater Eurasian partnership and the Belt and Road Initiative: Can the two be linked?. Journal of Eurasian Studies, 9(2), 94-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euras.2018.07.004

[22]. Ye, M. (2021). Adapting or Atrophying? China’s Belt and Road after the Covid-19 Pandemic. Asia Policy, 28(1), 65-95. https://doi.org/10.1353/asp.2021.0004

[23]. Keuper, M. The Implications of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on the Future of Sino-European Overland Connectivity. https://euagenda.eu/upload/publications/aies-fokus-2022-06.pdf

[24]. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (2023, May 19). President Xi Jinping Chairs the Inaugural China-Central Asia Summit and Delivers a Keynote Speech. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/202305/t20230519_11080116.html

[25]. Dreyer, J. T. (2015). The ‘Tianxia Trope’: will China change the international system?. Journal of Contemporary China, 24(96), 1015-1031. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2015.1030951

[26]. Kang, L., Peng, F., Zhu, Y., & Pan, A. (2018). Harmony in diversity: can the one belt one road initiative promote China’s outward foreign direct investment?. Sustainability, 10(9), 3264. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/su10093264

[27]. Passi, R (2018). Unpacking Economic Motivations and Non-economic Consequences of Connectivity Infrastructure Under OBOR. In Xing, L. (Ed.). Mapping China’s “One belt one road” initiative (pp. 167-195). Palgrave Macmillan. https://link-springer-com.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/book/10.1007/978-3-319-92201-0

[28]. Myers, M. (2018). China’s belt and road initiative: what role for Latin America?. Journal of Latin American Geography, 17(2), 239-243. https://doi.org/10.1353/lag.2018.0037

[29]. Jonathan E. Hillman. (2018, September 4). China’s Belt and Road Is Full of Holes. Center For Strategic International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-belt-and-road-full-holes

[30]. Khan, H., Weili, L., & Khan, I. (2022). The role of financial development and institutional quality in environmental sustainability: panel data evidence from the BRI countries. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-21697-7

[31]. Corruption Perceptions Index (2022). Transparency International. https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2022

[32]. WJP Rule of Law Index (2023). World Justice Project. https://worldjusticeproject.org/rule-of-law-index/global/2023/China/

[33]. Mukhtar, A., Zhu, Y., Lee, Y. I., Bambacas, M., & Cavusgil, S. T. (2022). Challenges confronting the ‘One Belt One Road’initiative: Social networks and cross-cultural adjustment in CPEC projects. International Business Review, 31(1), 101902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2021.101902

[34]. Zhou, Y., Kundu, T., Goh, M., & Sheu, J. B. (2021). Multimodal transportation network centrality analysis for Belt and Road Initiative. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 149, 102292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2021.102292

[35]. Irshad, M. S. (2015). One belt and one road: dose China-Pakistan economic corridor benefit for Pakistan’s economy?. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 6(24). https://ssrn.com/abstract=2710352

[36]. Wang, J. J., & Selina, Y. A. U. (2018). Case studies on transport infrastructure projects in belt and road initiative: An actor network theory perspective. Journal of Transport Geography, 71, 213-223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.01.007

[37]. Shah, A. R. (2023). Revisiting China threat: the US’securitization of the ‘Belt and Road Initiative’. Chinese Political Science Review, 8(1), 84-104.

[38]. Petry, J. (2023). Beyond ports, roads and railways: Chinese economic statecraft, the Belt and Road Initiative and the politics of financial infrastructures. European Journal of International Relations, 29(2), 319-351.

[39]. Plamem Toncheve. (2020, April 7). The Belt and Road After COVID-19. The Diplomat. The Belt and Road After COVID-19 – The Diplomat

Cite this article

Xiao,S. (2024). Is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and China’s Growing Global Interconnectivity More Generally, Generating Network Effects and Lock-In Dynamics?. Journal of Applied Economics and Policy Studies,2,25-50.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Journal of Applied Economics and Policy Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Siddiqui, K. (2019). One Belt and One Road, China’s massive infrastructure project to boost trade and economy: an overview. International Critical Thought, 9(2), p. 224, 214-235. https://doi.org/10.1080/21598282.2019.1613921

[2]. Xing, L. (2018). China’s Pursuit of the “One Belt One Road” Initiative: A New World Order with Chinese Characteristics? In Xing, L. (Ed.). Mapping China’s “One belt one road” initiative (pp. 1-27). Palgrave Macmillan. https://link-springer-com.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/book/10.1007/978-3-319-92201-0

[3]. Chung, C. P. (2018). What are the strategic and economic implications for South Asia of China’s Maritime Silk Road initiative?. The Pacific Review, 31(3), p. 7, 315-332. https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2017.1375000

[4]. Merwe, J. V. D. (2018). The One Belt One Road Initiative: Reintegrating Africa and the Middle East into China’s System of Accumulation. In Xing, L. (Ed.). Mapping China’s “One belt one road” initiative (p. 200, pp. 197-217). Palgrave Macmillan. https://link-springer-com.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/book/10.1007/978-3-319-92201-0

[5]. Xing, L. (2018). China’s Pursuit of the “One Belt One Road” Initiative: A New World Order with Chinese Characteristics? In Xing, L. (Ed.). Mapping China’s “One belt one road” initiative (pp. 1-27). Palgrave Macmillan. https://link-springer-com.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/book/10.1007/978-3-319-92201-0

[6]. Battamo, A. Y., Varis, O., Sun, P., Yang, Y., Oba, B. T., & Zhao, L. (2021). Mapping socio-ecological resilience along the seven economic corridors of the Belt and Road Initiative. Journal of Cleaner Production, 309, 127341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127341

[7]. Flint, C., & Zhu, C. (2019). The geopolitics of connectivity, cooperation, and hegemonic competition: The Belt and Road Initiative. Geoforum, 99, 95-101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.12.008

[8]. Druzin, B. H. (2020). Can the Liberal Order be Sustained? Nations, Network Effects, and the Erosion of Global Institutions. Mich. J. Int’l L., 42, 1. https://web-p-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=0&sid=e0a7bc3b-23df-4ab1-a81b-88c43215e151%40redis

[9]. Vangeli, A. (2018). A Framework for the Study of the One Belt One Road Initiative as a Medium of Principle Diffusion. In Xing, L. (Ed.). Mapping China’s “One belt one road” initiative (pp. 57-89). Palgrave Macmillan. https://link-springer-com.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/book/10.1007/978-3-319-92201-0