Global Financial Inclusion, Global Findex Database Report, Inclusive Finance, Digital Inclusive Finance, Regional Disparities

1 Introduction

In 2005, the United Nations introduced the concept of Financial Inclusion, which refers to the process of ensuring that all members of an economy have easy access to, and are able to use, the financial system [2]. Financial Inclusion aims to remove barriers that prevent people from participating in the financial sector and using these services to improve their lives, hence it is also known as Inclusive Finance. Inclusive Finance can serve consumers in remote areas, specific genders, certain age groups, or other marginalized communities, and can foster greater overall innovation, economic growth, and consumer knowledge [3]. Advances in financial technology, such as digital transactions, have made access to achieving Inclusive Finance easier. In recent years, Financial Inclusion has become a priority for many countries and a significant topic in various international forums [4]. As early as 2005, the construction of an Inclusive Financial System was proposed by the United Nations as a crucial means to achieve the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Following the outbreak of the financial crisis in 2008, Financial Inclusion garnered widespread attention from the international community. Particularly, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has severely impacted the global economy, making economic recovery and relief urgent priorities. Financial Inclusion, as a vital means to advance this process and a hot topic in the financial sector, merits more in-depth discussion and analysis.

This study will explore global Financial Inclusion issues from the following perspectives. First, what are the operating mechanisms of Financial Inclusion, and how does it serve individual consumers and companies? Second, a comprehensive analysis of the state of Financial Inclusion across different regions and countries worldwide. Third, an exploration of the reasons underlying the disparities in Financial Inclusion across various regions and countries. Fourth, some feasible recommendations to address the regional differences in Financial Inclusion.

2 Operating Mechanisms of Financial Inclusion

Since its proposal by the United Nations in 2005, Inclusive Finance has been continuously serving people in various countries and regions worldwide. Inclusive Finance can make daily life more convenient, help families and businesses plan for long-term goals, and respond to unexpected emergencies. With the global spread of this concept since 2009, the most direct manifestation has been the steady increase in account ownership worldwide. According to the World Bank Group (WBG), by 2021, approximately 76% of adults globally owned some type of account, up from about 25% in 2011. The increase in account ownership means that people can better and more efficiently enjoy the benefits of Inclusive Finance. Specifically, they can participate in savings, credit, and insurance, start and expand businesses, and invest in education or health. At the same time, they can enhance risk management to cope with financial shocks, all of which can improve their overall living standards and quality of life. Although many obstacles and difficulties remain, the situation is gradually improving. Financial Inclusion primarily operates through the following aspects:

2.1 Accessibility

Accessibility is one of the most fundamental yet crucial means to achieve Financial Inclusion. Financial services should be easily accessible, which includes increasing the accessibility rate of financial services. As noted above, in 2021, about 76% of individuals globally owned an account, meaning that approximately three-quarters of the global population could access formal financial services. Additionally, the emerging concept of “Digital Inclusive Finance”combines digital technology with Inclusive Finance, reducing service thresholds and transaction costs, and increasing the geographical and network coverage of financial services. This allows more people in remote areas to be included in the formal financial service system.

2.2 Affordability

Apart from accessibility, the pricing of financial services should be affordable for consumers, including vulnerable groups. For providers, reasonable pricing means that financial service institutions can sustainably offer financial services.

2.3 Security

On the premise of accessibility and affordability, Financial Inclusion also ensures the legal rights of account holders. The legitimacy of transactions, transparent service terms, and effective complaint mechanisms are essential conditions to ensure the security aspect of Financial Inclusion.

2.4 Comprehensiveness

The design of financial products and services should meet the diverse needs of various consumers. While ensuring the accessibility of basic services like deposits, loans, remittances, and insurance, it should make further efforts to enhance the diversity of related services. For example, upgrading the financial service system to offer comprehensive services such as payments, wealth management, investment, financing, and credit reporting can further ensure the spread of Financial Inclusion [5].

3 Current State of Global Financial Inclusion

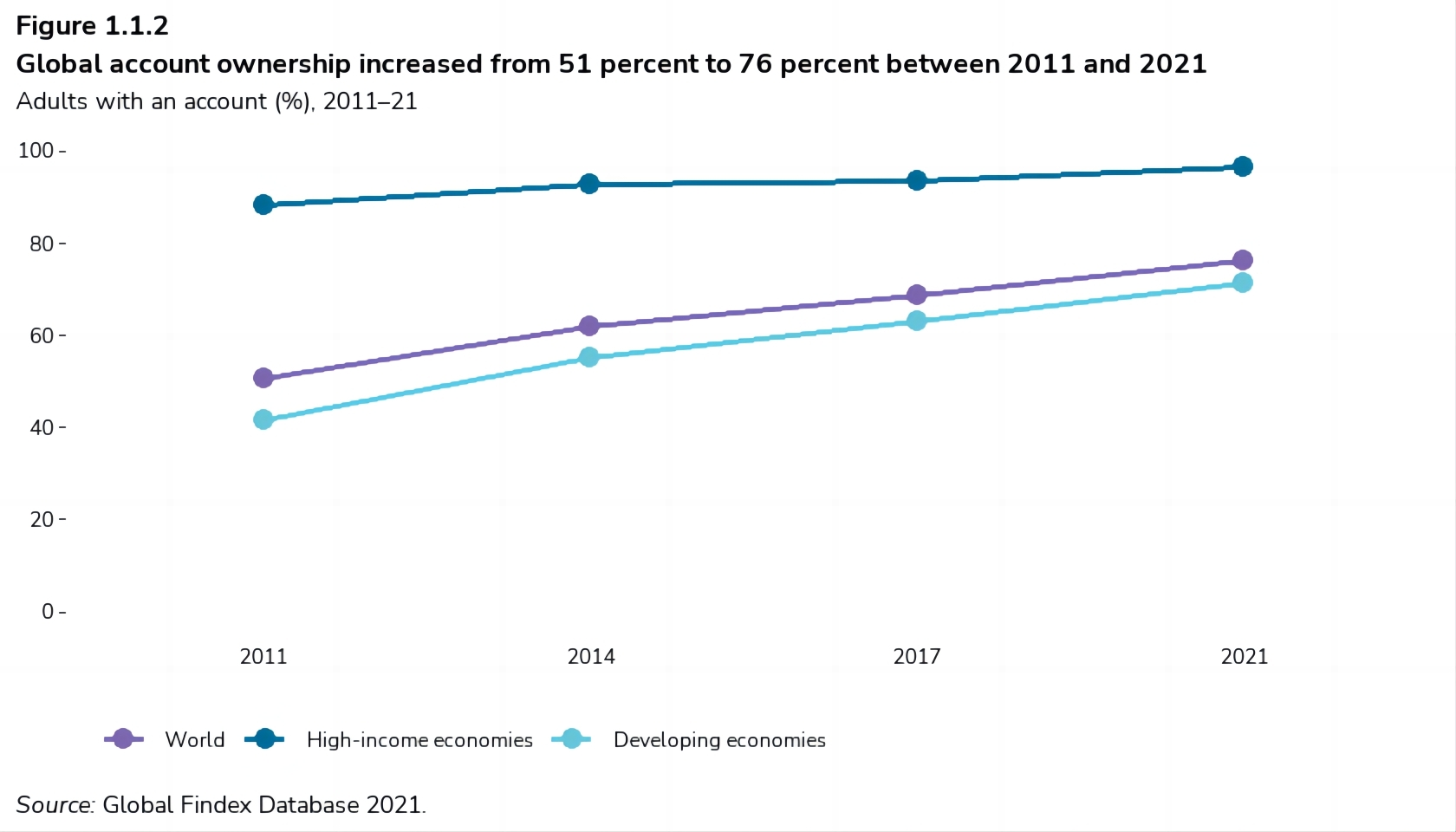

3.1 Significant Increase in Global Account Ownership

According to the 2021 Global Findex Database, as of June 2021, about 76% of adults worldwide had an account (either a bank account or a digital payment account), a significant increase from 51% in 2011, and this trend continues to rise (see Figure 1). Although both high-income and developing economies have seen increased account ownership, the growth in developing economies is more pronounced (71%), up by approximately 29% since 2011 (see Figure 1). Additionally, the newly added accounts since 2017 come from dozens of different economies, unlike the 2011-2017 period when most were concentrated in India and China. Since 2017, countries such as Brazil, Ghana, Morocco, and South Africa have experienced double-digit growth in account ownership. However, there is still a significant number of unbanked individuals in developing economies, about 1.4 billion. For high-income economies, account ownership has been nearly universal since 2011 (reaching 88%) and has increased to 96% over the past decade. In Poland and Italy, account ownership has grown by more than 20% over these ten years.

Figure 1. Global account ownership growth between 2011 and 2021[]

3.2 Mobile Payments as a Pillar of Financial Inclusion

In 2021, about 18% of adults in developing countries paid utility bills directly from their accounts, an increase of approximately 10% from 2014. In China, about 80% of adults used digital merchant payments, and in other developing countries, around 720 million adults utilized this service. Additionally, measures like social distancing enforced due to the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of digital financial services. Outside of China, about 40% of adults in developing countries used credit or debit cards, mobile phones, or the internet for digital merchant payments for the first time, and over one-third paid utility bills directly from their accounts for the first time. In sub-Saharan Africa, mobile payments have also become a crucial means to promote financial inclusion, particularly for female account holders. Mobile and digital payments not only increased account ownership but also enhanced account usage through payments, savings, and loans.

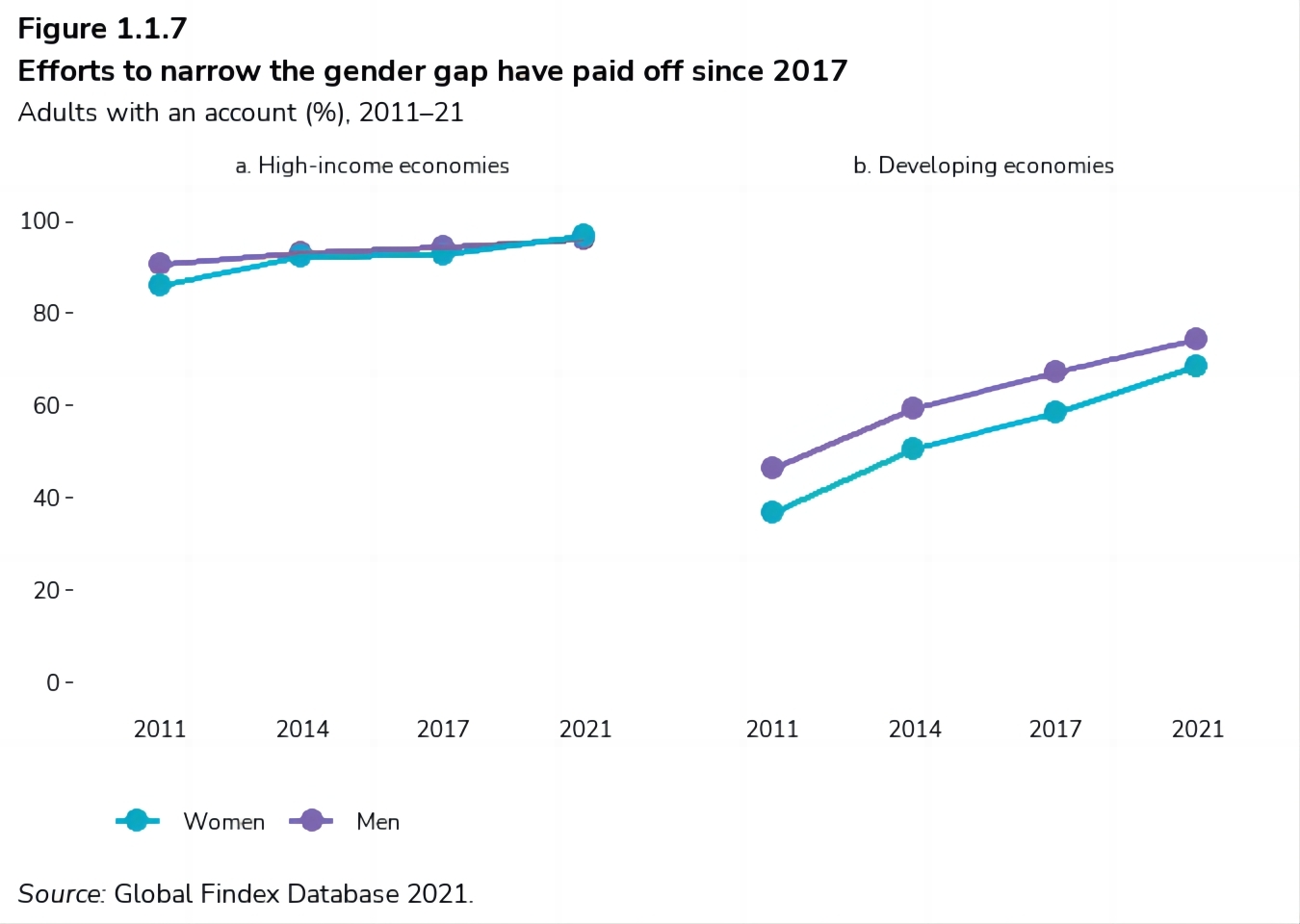

3.3 Narrowing Gender Gap in Account Ownership

The gender gap in account ownership is gradually narrowing, decreasing from 9% to 6%, with 68% of women and 74% of men holding accounts in 2021 (see Figure 2). Globally, 74% of women and 78% of men had accounts in 2021, indicating a gender difference of only 4%. This demonstrates that efforts by countries worldwide to reduce the gender gap in account ownership have begun to show positive results.

Figure 2. Gender gap in account ownership between 2011 and 2021[1]

3.4 Large Unbanked Population Worldwide

Despite significant improvements in financial inclusion, particularly in account ownership and gender disparities, a large number of adults worldwide (1.4 billion) still do not have any type of account. This means that about 17% of adults globally lack access to financial services, with around 85 million people still receiving government benefits in cash. However, with the promotion of digital payments, it is expected that more recipients will be integrated into the formal financial system, reducing government expenses and curbing corruption [6]. As of 2021, approximately 865 million people globally had opened accounts to receive government benefits.

4 Regional Disparities and Causes of Global Financial Inclusion

As evidenced by the above analysis, efforts to improve financial inclusion globally have achieved initial success, but significant disparities remain among different economies. The specific manifestations and causes of these disparities warrant attention.

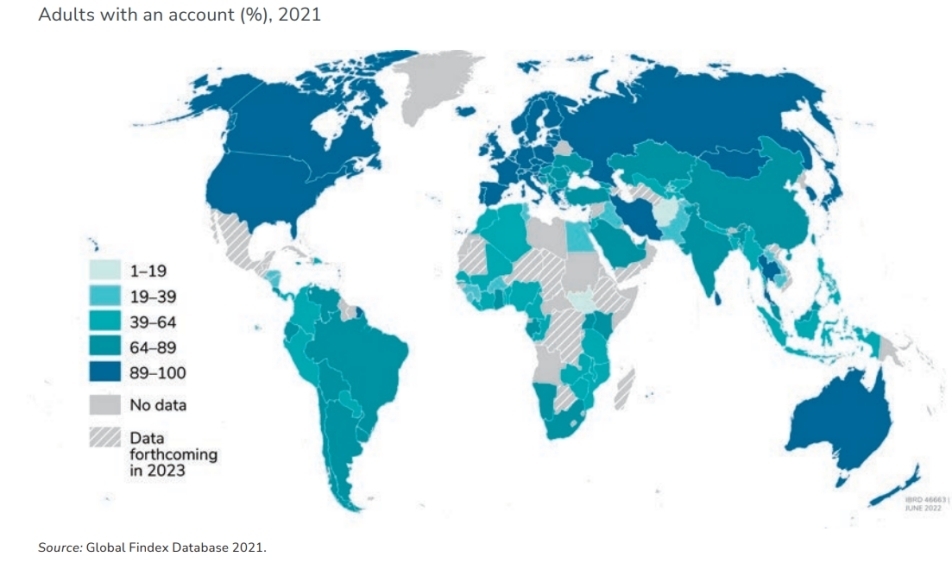

4.1 Uneven Distribution of Account Ownership

Although global account ownership significantly increased in 2021, there is still a substantial number of unbanked individuals, approximately 1.4 billion, meaning that around 24% of adults globally lack access to formal financial services. Vulnerable groups, particularly the poor with low education levels, find it harder to obtain financial services. These individuals mainly reside in the following regions concentrated in developing countries: South Asia, East Asia and the Pacific, the Middle East and North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Europe and Central Asia. Over half of the unbanked population (around 740 million) come from seven developing countries: India, China, Pakistan, Indonesia, Nigeria, Egypt, and Bangladesh (ranked from highest to lowest). This directly reflects the persistent gap in financial inclusion between economies with different development levels. The main reasons for low financial inclusion in developing economies include: 1. lack of money to save, which is the most common reason; 2. most respondents believe they cannot afford the service fees of financial institutions; 3. financial institutions are too far away, especially in impoverished regions like sub-Saharan Africa; 4. in some less developed countries, many female respondents indicate they do not have accounts because they share finances with family members. In summary, the global distribution of account ownership remains unbalanced, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Account ownership rates across the world [1]

4.2 Significant Gaps in Financial Health

4.2.1 Differences in Financial Resilience

Financial resilience is one of the reasons for the disparity in financial inclusion. Financial resilience can be understood as the ability of businesses or individuals to manage finances in the face of economic shocks or emergencies [7]. The 2021 Global Findex survey posed three questions to assess the financial resilience of populations in different economies: 1. What are the sources of emergency funds within the next 30 days? 2. How difficult is it to obtain these funds within the next 30 days? 3. How about if the time-frame is shortened to seven days? They found that adults in different economies prioritize different emergency funding sources, with about 50% of respondents from high-income economies using savings, while around 60% from developing economies rely mainly on social relationships or income from work. However, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in many respondents losing their jobs, significantly reducing the reliability of these sources. Additionally, the report shows that in high-income economies, about 68% of adults believe it is easy (or only slightly difficult) to raise emergency funds within seven days, compared to 41% in developing economies. When the time-frame is extended to 30 days, the figures are 79% and 55%, respectively. Thus, apart from individual differences such as income levels, preferences, and specific behavioral patterns, cultural, policy, and financial development backgrounds also contribute to the disparities in financial resilience among different economies.

4.2.2 Widespread Financial Concerns in Developing Economies

Besides the level of financial resilience, the degree of anxiety or concern about one’s financial situation is also a measure of financial inclusion. According to the 2021 Global Findex Database report, common financial concerns among respondents include, but are not limited to, the following four areas: retirement costs, medical expenses due to major illness or accidents, monthly bills (or expenses), and education costs. Respondents from developing economies are more likely to worry about these issues than those from high-income economies. In developing economies, about 52% of respondents are most concerned about medical expenses, compared to only about 20% in high-income economies. A similar proportion of respondents in developing economies worry about being unable to afford retirement costs. This situation is most severe in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, accounting for about 64% of their total respondents. The backwardness and lack of transparency in the education system make education expenses the second largest concern in sub-Saharan Africa, accounting for about 54% of respondents. Additionally, gender differences and the wealth gap also cause varying degrees of financial concern. Generally, women and poorer populations are more likely to worry about future finances. In developing economies, about 44% of female respondents worry about monthly expenses or bills, 5% higher than their male counterparts. This may relate to the different roles that genders assume in household financial management in specific economies.

4.3 Varied Usage Rates of Financial Services

The use of financial services shows regional disparities, as reported in the Global Financial Inclusion Index Database. The report covers aspects such as digital payments, savings, and borrowing. Firstly, in developing economies, the percentage of respondents using digital payments rose from 35% in 2014 to 57% in 2021, surpassing the growth rate of account ownership during the same period. However, this usage rate is still far below the 95% rate observed in high-income economies. In many developing countries, residents still use cash to pay utility bills. Secondly, regarding savings, more respondents in high-income economies save for retirement, which may explain why they are less concerned about retirement costs. Lastly, concerning borrowing, about 53% of respondents worldwide had borrowed money in the past year, but the sources of loans varied significantly across economies. In developing economies, less than half of the respondents (46%) borrowed from financial institutions, using credit cards, or mobile payment accounts. They preferred informal channels such as borrowing from family or savings clubs. This reflects the poorer financial inclusion in developing economies, as a primary goal of financial inclusion is to enable account holders to benefit from financial services. Clearly, these borrowers did not feel the benefits of financial inclusion.

5 Recommendations to Improve Regional Disparities in Financial Inclusion

5.1 Accelerate the Increase in Account Ownership Rates

Governments, especially in developing countries, can expand financial inclusion by increasing account ownership rates. The report indicates that in sub-Saharan Africa, over 100 million adults cannot open accounts due to the lack of valid identification. Having valid identification would allow them to purchase mobile SIM cards, meaning more people could use digital payments. This is particularly important in impoverished and remote areas where transportation and information dissemination are challenging. This could be the fastest way for them to make digital payments without bank cards. Additionally, many feel unsafe using accounts without assistance, a situation prevalent among vulnerable groups. Governments and relevant authorities need to provide more support to these groups, further improving their financial literacy. If installing ATMs is challenging, local governments should strengthen cooperation with post offices or small shops, designating them as agent banks to provide financial services.

5.2 Promote the Adoption of Digital Payments

To address regional disparities in financial service provision, governments should continue to promote the digitization of payments. Digital Inclusive Finance, formally proposed by the G20 Summit in 2016, leverages internet technology to offer high-quality financial services to remote and underdeveloped areas without spatial and temporal limitations [8,9]. Promoting the digitization of inclusive finance can effectively address the scarcity and limited coverage of financial resources in poor regions [10]. The concept of digital inclusive finance aligns closely with the idea of inclusive growth [11]. Currently, many banks have launched and promoted mobile banking Apps, offering services such as transfers, digital payments, and microloans, further enhancing convenience. As financial services gradually move online, costs and service thresholds are reduced, allowing financial institutions to include more regions within their service range. Therefore, digital inclusive finance is an inevitable product of technological progress and a major direction for the development of inclusive finance, significantly boosting global financial inclusion. To promote the shift from cash to digital payments in poor and underdeveloped areas, governments and institutions should enhance regulation to make digital inclusive finance safer and more transparent, ensuring that users in these regions actively use relevant services. Additionally, improving the power and network infrastructure in these areas is crucial as it canprovide residents with reliable information technology support.

5.3 Collaborative Efforts to Enhance Financial Inclusion

Improving financial inclusion and reducing financial disparities should be a joint effort by consumers, regulatory bodies, and financial institutions. On one hand, as the coverage of digital payments expands, regulatory bodies should develop more sophisticated regulatory systems, identifying and recognizing common risks in the financial market and their frequency, and informing consumers in advance. On the other hand, financial institutions should disclose product characteristics and fees, ensuring that consumers are fully informed. Particularly for those with lower education levels and other vulnerable groups, financial institutions have the responsibility to clearly communicate predatory financial behaviors and their risks in plain language [12]. High annual interest rates, mandatory terms, and hefty penalties for early repayment all exploit consumers’ short-term spending capacity and violate the intent of inclusive finance [12]. Financial institutions can collaborate with regulatory bodies to conduct financial literacy workshops for residents, enhancing their financial awareness and safeguarding their interests.

6 Conclusion

As of 2021, inclusive finance has broadly served approximately 76% of the global population, significantly improving people’s quality of life and living standards worldwide. The accessibility and affordability of financial inclusion have brought more vulnerable groups into the inclusive finance process. At the same time, the widespread adoption of digital payments has greatly reduced gender and wealth disparities in financial service usage. However, the process of enhancing financial inclusion still faces considerable challenges, and financial exclusion remains a prominent issue. This is specifically reflected in the following areas. First, there are still about 1.4 billion unbanked people globally, accounting for about 24% of the world’s population, mainly concentrated in developing regions. Second, disparities in financial resilience require the attention of governments worldwide. Third, residents of developing countries are more likely to be concerned about their financial situation, indicating that the spread of inclusive finance needs to be further enhanced. Fourth, there are significant regional disparities in the use of financial services, including savings and borrowing reasons. Promoting the widespread adoption of digital payments, strengthening market regulation, and improving users’ financial literacy are urgent priorities. These disparities indicate that the process of enhancing global financial inclusion is fraught with difficulties and requires the collaborative efforts of governments worldwide.

References

[1]. Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., & Ansar, S. (2022). The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial inclusion, digital payments, and resilience in the age of COVID-19. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1897-4

[2]. Ren, K., Wang, Y., & Liu, L. (2023). Impact of traditional and digital financial inclusion on enterprise innovation: Evidence from China. Sage Open, 13(1), 1–19.

[3]. Zhou, X. (2016, March 18). Better development of inclusive finance [EB/OL]. Financial News. https://www.financialnews.com.cn/jg/ld/201603/t20160318_94145.html

[4]. Wang, X., He, M., & Guan, J. (2014). Research progress on financial inclusion theory and practice. Economic Dynamics, (11), 115–129.

[5]. Xing, Y. (2016). Inclusive finance: A basic theoretical framework. International Financial Research, (09), 21–37.

[6]. Ansar, A., Wang, J. J., Panchamia, M. V., & others. (2022, June 29). Understanding the 2021 Global Financial Inclusion Index Database through five charts [EB/OL]. World Bank Blogs. https://blogs.worldbank.org/zh-hans/voices/unveiling-global-findex-database-2021-five-charts

[7]. Barbera, C., Guarini, E., & Steccolini, I. (2020). How do governments cope with austerity? The roles of accounting in shaping governmental financial resilience. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 33(3), 529–558.

[8]. Li, M., & Feng, S. (2020). Digital inclusive finance and urban-rural income gap: An analysis based on literature. Contemporary Economic Management, 42(10), 84–91.

[9]. Wang, H., & Dou, X. (2024, May 22). Research on the impact of digital inclusive finance on narrowing the urban-rural income gap [J/OL]. Journal of Chongqing University of Science and Technology (Social Science Edition). http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/50.1175.C.20240521.1716.002.html

[10]. Zhao, Y., Shi, G., Xu, J., & others. (2022). Research on digital inclusive finance supporting rural revitalization. National Circulation Economy, (04), 147–149.

[11]. Ye, W., & Gong, L. (2023). Digital inclusive finance and inclusive growth: Theoretical analysis and prospects. Economic Issues, (12), 49–57.

[12]. Zhao, X. (2015). Predatory lending and financial consumer protection. Corporate Finance Research, (2), 69–79.

Cite this article

Guo,L. (2024). Global Financial Inclusion: Mechanisms, Regional Disparities, and Recommendations for Improvement. Journal of Applied Economics and Policy Studies,7,39-44.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Journal of Applied Economics and Policy Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., & Ansar, S. (2022). The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial inclusion, digital payments, and resilience in the age of COVID-19. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1897-4

[2]. Ren, K., Wang, Y., & Liu, L. (2023). Impact of traditional and digital financial inclusion on enterprise innovation: Evidence from China. Sage Open, 13(1), 1–19.

[3]. Zhou, X. (2016, March 18). Better development of inclusive finance [EB/OL]. Financial News. https://www.financialnews.com.cn/jg/ld/201603/t20160318_94145.html

[4]. Wang, X., He, M., & Guan, J. (2014). Research progress on financial inclusion theory and practice. Economic Dynamics, (11), 115–129.

[5]. Xing, Y. (2016). Inclusive finance: A basic theoretical framework. International Financial Research, (09), 21–37.

[6]. Ansar, A., Wang, J. J., Panchamia, M. V., & others. (2022, June 29). Understanding the 2021 Global Financial Inclusion Index Database through five charts [EB/OL]. World Bank Blogs. https://blogs.worldbank.org/zh-hans/voices/unveiling-global-findex-database-2021-five-charts

[7]. Barbera, C., Guarini, E., & Steccolini, I. (2020). How do governments cope with austerity? The roles of accounting in shaping governmental financial resilience. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 33(3), 529–558.

[8]. Li, M., & Feng, S. (2020). Digital inclusive finance and urban-rural income gap: An analysis based on literature. Contemporary Economic Management, 42(10), 84–91.

[9]. Wang, H., & Dou, X. (2024, May 22). Research on the impact of digital inclusive finance on narrowing the urban-rural income gap [J/OL]. Journal of Chongqing University of Science and Technology (Social Science Edition). http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/50.1175.C.20240521.1716.002.html

[10]. Zhao, Y., Shi, G., Xu, J., & others. (2022). Research on digital inclusive finance supporting rural revitalization. National Circulation Economy, (04), 147–149.

[11]. Ye, W., & Gong, L. (2023). Digital inclusive finance and inclusive growth: Theoretical analysis and prospects. Economic Issues, (12), 49–57.

[12]. Zhao, X. (2015). Predatory lending and financial consumer protection. Corporate Finance Research, (2), 69–79.