1. Introduction

Amid the ongoing transformation of the global energy landscape and the implementation of carbon neutrality strategies, developing high-safety electrochemical energy storage technologies has become a core issue for the large-scale adoption of renewable energy. For energy storage in extreme environments, the development of low-temperature solid-state lithium-ion batteries holds significant theoretical value and engineering potential. Breakthroughs in this technology play a key role in advancing both military-civil fusion strategies and the construction of modern technological systems [1].As activities such as high-altitude exploration and polar expeditions expand, and as emerging fields like new energy vehicles and space navigation equipment continue to evolve, the performance stability of energy storage devices under low-temperature conditions has become a major bottleneck for their practical application. This challenge mainly arises because, at low temperatures, the electrolyte tends to solidify, which dramatically increases charge transfer impedance and slows down interfacial kinetics, resulting in degraded battery performance. Research into solid-state electrolyte systems presents an important technological pathway to overcome these problems.

Currently, this field faces three main technological bottlenecks. First, failure at the solid–solid interface disrupts charge transport pathways, requiring interface modification strategies to construct three-dimensional conductive channels. Second, while sulfide-based electrolytes offer high ionic conductivity, they suffer from a trade-off between chemical stability and manufacturing feasibility, which hinders their industrialization. Existing element doping approaches have not fully resolved the inherent material defects. Third, oxide-based electrolytes need to overcome high grain boundary resistance, while polymer-based materials face challenges in achieving a balance between mechanical strength and ionic conductivity. These challenges demonstrate that despite promising research progress, the practical application of solid-state electrolytes still faces significant hurdles.

Solid-state electrolytes are the core component of all-solid-state batteries and are generally categorized into four main types: oxides, sulfides, polymers, and composite electrolytes. Perovskite-type electrolytes, such as LLTO, offer relatively high ionic conductivity (~10⁻⁴ S/cm), but suffer from severe interfacial side reactions with metallic sodium. Garnet-type electrolytes, like LLZO, have excellent chemical stability but require sintering at temperatures above 1200 °C, which leads to high grain boundary resistance. Sulfide-based electrolytes, such as Na₃PS₄, exhibit ionic conductivities up to 10⁻³ S/cm at room temperature, but are extremely sensitive to moisture and lack thermal stability [2]. In contrast, NASICON-type sodium superionic conductors have attracted significant attention due to their three-dimensional interconnected pore structures, wide electrochemical window, and excellent thermal stability [3].

In this paper, we systematically summarize several key aspects of NASICON-type electrolytes—as shown in Figure 1—including their crystal structures, ion transport mechanisms, practical applications, and doping modification strategies. We aim to provide a comprehensive overview of the current challenges facing NASICON materials and offer forward-looking perspectives and potential solutions.

2. Crystal Structure and Ion Transport Mechanism of Nasicon-type Lithium-ion Electrolytes

2.1. Crystal Structure Characteristics

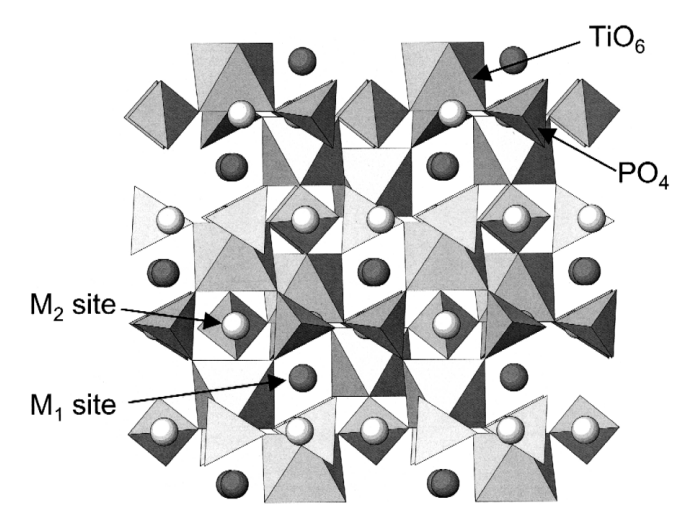

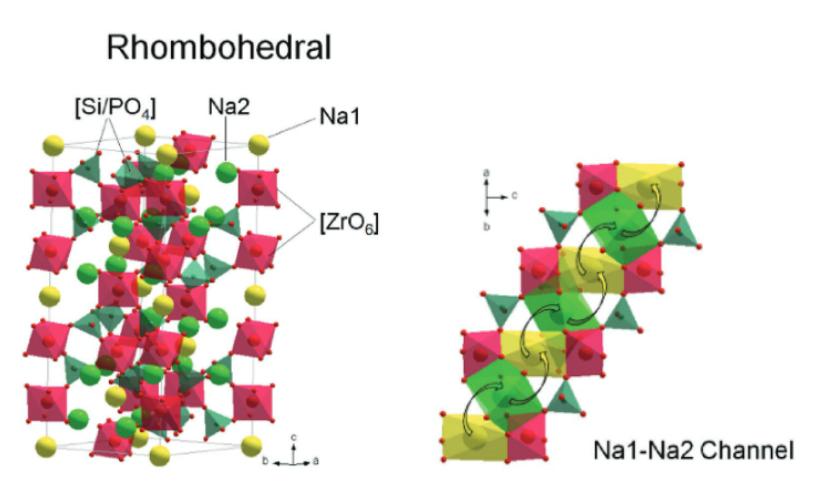

NASICON-type solid electrolytes generally adopt the formula AM'M''P₃O₁₂, where A is a monovalent alkali metal cation (e.g., Li⁺, Na⁺, or K⁺), and M', M'' are multivalent metal cations such as Ti⁴⁺, Zr⁴⁺, or Ge⁴⁺. When A is lithium, the compound becomes a NASICON-type lithium-ion electrolyte, typically with the formula Li(A₂P₃O₁₂). The structure comprises a three-dimensional framework of interconnected [AO₆] octahedra and [PO₄] tetrahedra, creating open ion-conducting channels. Lithium ions mainly occupy the M1 sites, which are octahedrally coordinated and provide low-energy migration pathways, while M2 sites in interstitial spaces assist in ion diffusion. Doping with ions like Ti⁴⁺ at M2 sites can distort the lattice and widen migration channels, improving ionic conductivity. Despite these favorable structural features, performance is still limited by factors such as material densification and the concentration of mobile lithium ions [4].

2.2. Ion Transport Mechanism

Li⁺ ions in NASICON-type structures migrate through a three-dimensional network via two main pathways: straight channels along the c-axis and zigzag routes involving hopping between M1 and M2 sites. This migration is influenced by local energy barriers caused by distortions in the [MO₆] octahedra. Enhancing ionic conductivity depends on minimizing these distortions and improving channel connectivity [5].For instance, doping with Sc³⁺ reduces activation energy to around 0.2 eV, enabling conductivities up to 10⁻³ S/cm at room temperature. However, excessive Li⁺ concentration (>50%) can lead to electrostatic repulsion and hinder diffusion. Thus, optimizing the M-site environment through doping (e.g., with Sc³⁺ or Al³⁺) is critical for improving ion transport performance in NASICON electrolytes.

3. Applications of Nasicon-type Solid Electrolytes

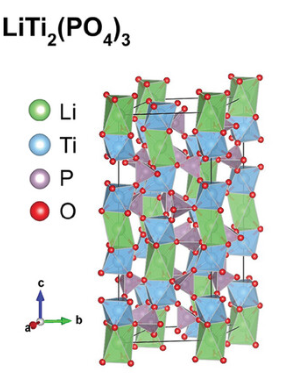

3.1. LiTi₂(PO₄)₃ (LTP)

LiTi₂(PO₄)₃ (LTP) is a representative NASICON-type solid electrolyte, demonstrating excellent battery performance with a discharge capacity of 80 mAh·g⁻¹ when used with a LiMn₂O₄ thin-film cathode, as shown by Dokko et al [6]. using a sol–gel coating method. The synthesis approach significantly affects LTP’s properties; for example, Sharma et al. enhanced grain boundary conductivity by forming a glass–ceramic composite through ball-milling LTP with ion-conducting glass ((Li₂SO₄)₃–(LiPO₃)₂), achieving an ionic conductivity of ~10⁻⁴ S/cm at room temperature.

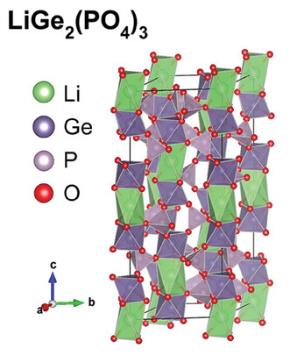

3.2. LiGe2(PO4)3(LGP)

LiGe₂(PO₄)₃ (LGP) is a NASICON-type solid electrolyte with mobile Li⁺ ions and exhibits high ionic conductivity (~10⁻⁴ S/cm) when doped with Al³⁺. Unlike LiTi₂(PO₄)₃ (LTP), which suffers from Ti⁴⁺ undergoing redox reactions with lithium metal, compromising stability, LGP’s Ge⁴⁺ is more chemically stable. Additionally, LGP offers a wide electrochemical stability window (1.8–7 V), making it a promising candidate for high-voltage lithium-ion batteries [7].

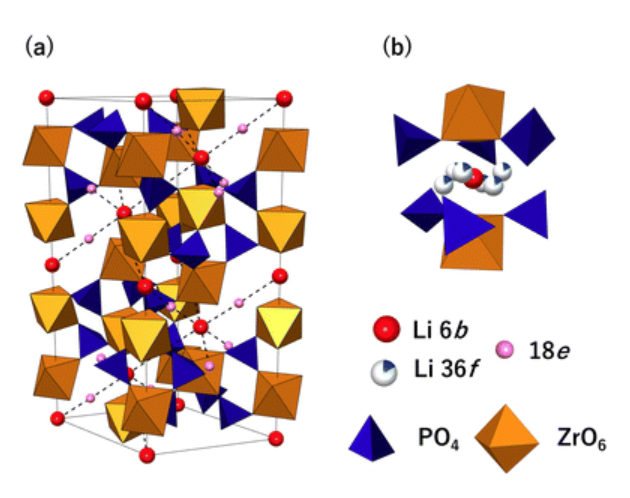

3.3. LiZr2(PO4)3(LZP)

LiZr₂(PO₄)₃ (LZP) is a NASICON-type solid electrolyte with good compatibility with lithium metal and moderate ionic conductivity (~5 × 10⁻⁶ to 2 × 10⁻⁴ S/cm), attributed to Frenkel-type defect migration. Unlike LTP and LGP, LZP forms a stable solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) through redox reactions with lithium, enhancing interfacial stability [8]. It remains electrochemically stable up to 5.5 V and demonstrates good cycling performance, with discharge capacities of 140 and 120 mAh·g⁻¹ at different current densities. However, its lower conductivity compared to titanium-based materials and higher processing demands limit broader application [9].

4. Preparation Methods of Nasicon-type Lithium-ion Electrolytes

4.1. Conventional Synthesis Techniques

Conventional methods for preparing NASICON-type lithium-ion electrolytes include high-temperature solid-state reactions and the sol–gel method [10].The solid-state method involves mixing oxide precursors and calcining at >1000 °C, offering simplicity and low cost but suffering from issues like uneven particle size and high grain boundary resistance[11].In contrast, the sol–gel method forms nanoscale powders through hydrolysis and low-temperature treatment (600–800 °C), yielding higher surface area and improved ionic conductivity (up to 6.15 × 10⁻⁴ S/cm) [12].Though more complex and costly, the sol–gel method is favored for producing high-performance NASICON electrolytes [13].

4.2. Emerging Preparation Techniques

Emerging techniques for synthesizing NASICON electrolytes include co-precipitation, spark plasma sintering (SPS), and melt-quenching. Co-precipitation yields fine, high-purity powders with enhanced conductivity (up to 4.2 × 10⁻⁴ S/cm). SPS enables rapid densification at lower temperatures, significantly reducing grain boundary resistance. Melt-quenching forms glass-ceramics with tunable phase composition and high ionic mobility, though it requires precise process control[14]. These advanced methods improve performance and highlight future efforts to simplify processing, ensure uniformity, and enhance material purity.

5. Modification Strategies and Performance Optimization

Modification strategies for NASICON-type electrolytes focus on reducing impedance from grain boundaries and the bulk phase through optimized synthesis and doping. A-site doping—by introducing lower-valence ions like Ca²⁺ or higher-valence ions such as Sc³⁺, Y³⁺, or Cr³⁺—can adjust lattice parameters, create vacancies, and widen Li⁺ migration channels, significantly enhancing ionic conductivity. Co-doping (e.g., Y³⁺/Er³⁺) further improves performance. Though less studied, P-site substitution—replacing PO₄ groups with [SiO₄] or [VO₄]—modifies the crystal framework, lowers migration barriers, and boosts conductivity.

6. Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite their advantages in ionic conductivity and stability, NASICON-type solid electrolytes face key challenges: limited ionic conductivity (typically ~10⁻³ S/cm), poor interfacial compatibility with lithium metal (e.g., Ti⁴⁺ reduction), and manufacturing difficulties due to high sintering temperatures and material costs. To overcome these issues, future research should explore broader doping strategies—including substitutions at M, P, or Li sites—and develop advanced composite materials to lower grain boundary resistance and enable efficient low-temperature Li⁺ transport, supporting the practical application of NASICON electrolytes.

References

[1]. Li Jing, LyuXiaojuan, ZhangFeng, et al.(2021). Recent AdvancesinSolid-State LithiumIonElectrolytes, Journal of Ceramics, 42(05): 717-731.

[2]. Dias J A, Santagneli S H, Messaddeq Y. (2020). Methods for lithium ion NASICON preparation: from solid-state synthesis to highly conductive glass-ceramics, TheJournal of Physical Chemistry C, 2020, 124(49): 26518-26539.

[3]. LIU Y, ZHOU X, QIU T, et al. (2024). Co-assembly of polyoxometalates and porphyrins as anode for high-performance lithium-ion batteries, Advanced Materials, 36(35): 2407705.

[4]. BI J, DU Z, SUN J, et al. (2023). On the road to the frontiers of lithium-ion batteries: Areview and outlook of graphene anodes, Advanced Materials, 35(16): 2210734.

[5]. WANG K, DU H, HE S, et al. (2021). Kinetically controlled, scalable synthesis of γ-FeOOH nanosheet arrays on nickel foam toward efficient oxygen evolution: The key role of in-situ-generated γ-NiOOH, Advanced Materials, 33(11): 2005587.

[6]. HANJ, JOHNSONI, CHENM. (2022). 3Dcontinuously porous graphene for energy applications, Advanced Materials, 34(15): 2108750.

[7]. HUANG H, SHI H, DAS P, etal.(2020). The chemistry and promising applications of graphene and porous graphene materials, Advanced Functional Materials, 30(41): 1909035.

[8]. LEE J, KIM C, CHEONG J Y, et al. (2022). An angstrom-level d-spacing control of graphite oxide using organofillers for high-rate lithiumstorage, Chem, 8(9): 2393-2409.

[9]. SUN J, LIU Y, LIU L, et al. (2022). Expediting sulfur reduction/evolution reactions with integrated electrocatalytic network: A comprehensive kinetic map, NanoLetters, 22(9): 3728-3736.

[10]. LI S, WANG K, ZHANG G, et al. (2022). Fast charging anode materials for lithium-ion batteries: Current status and perspectives, Advanced Functional Materials, 32(23): 2200796.

[11]. LEE S-M, KIM J, MOON J, et al. (2021). A cooperative biphasic MoOx-MoPx promoter enables a fast-charging lithium-ionbattery, Nature Communications, 12(1): 39.

[12]. LEGE N, HE X-X, WANG Y-X, et al. (2023). Reappraisal of hard carbon anodes for practical lithium/sodium-ion batteries from the perspective of full-cell matters, Energy & Environmental Science, 16(12): 5688-5720.

[13]. ZHAO H, LI J, ZHAO Q, et al. (2024). Si-based anodes: Advances and challenges in Li-ion batteries for enhanced stability, Electrochemical Energy Reviews, 7(1): 11.

[14]. LI Y, LI Q, CHAI J, et al. (2023). Si-based anode lithium-ion batteries: A comprehensive review of recent progress, ACS Materials Letters, 5(11): 2948-2970.

Cite this article

Peng,L. (2025). Potential Applications of NASICON-Structured Solid Electrolytes in Low-Temperature Lithium-Ion Batteries. Applied and Computational Engineering,181,14-21.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of CONF-FMCE 2025 Symposium: Semantic Communication for Media Compression and Transmission

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Li Jing, LyuXiaojuan, ZhangFeng, et al.(2021). Recent AdvancesinSolid-State LithiumIonElectrolytes, Journal of Ceramics, 42(05): 717-731.

[2]. Dias J A, Santagneli S H, Messaddeq Y. (2020). Methods for lithium ion NASICON preparation: from solid-state synthesis to highly conductive glass-ceramics, TheJournal of Physical Chemistry C, 2020, 124(49): 26518-26539.

[3]. LIU Y, ZHOU X, QIU T, et al. (2024). Co-assembly of polyoxometalates and porphyrins as anode for high-performance lithium-ion batteries, Advanced Materials, 36(35): 2407705.

[4]. BI J, DU Z, SUN J, et al. (2023). On the road to the frontiers of lithium-ion batteries: Areview and outlook of graphene anodes, Advanced Materials, 35(16): 2210734.

[5]. WANG K, DU H, HE S, et al. (2021). Kinetically controlled, scalable synthesis of γ-FeOOH nanosheet arrays on nickel foam toward efficient oxygen evolution: The key role of in-situ-generated γ-NiOOH, Advanced Materials, 33(11): 2005587.

[6]. HANJ, JOHNSONI, CHENM. (2022). 3Dcontinuously porous graphene for energy applications, Advanced Materials, 34(15): 2108750.

[7]. HUANG H, SHI H, DAS P, etal.(2020). The chemistry and promising applications of graphene and porous graphene materials, Advanced Functional Materials, 30(41): 1909035.

[8]. LEE J, KIM C, CHEONG J Y, et al. (2022). An angstrom-level d-spacing control of graphite oxide using organofillers for high-rate lithiumstorage, Chem, 8(9): 2393-2409.

[9]. SUN J, LIU Y, LIU L, et al. (2022). Expediting sulfur reduction/evolution reactions with integrated electrocatalytic network: A comprehensive kinetic map, NanoLetters, 22(9): 3728-3736.

[10]. LI S, WANG K, ZHANG G, et al. (2022). Fast charging anode materials for lithium-ion batteries: Current status and perspectives, Advanced Functional Materials, 32(23): 2200796.

[11]. LEE S-M, KIM J, MOON J, et al. (2021). A cooperative biphasic MoOx-MoPx promoter enables a fast-charging lithium-ionbattery, Nature Communications, 12(1): 39.

[12]. LEGE N, HE X-X, WANG Y-X, et al. (2023). Reappraisal of hard carbon anodes for practical lithium/sodium-ion batteries from the perspective of full-cell matters, Energy & Environmental Science, 16(12): 5688-5720.

[13]. ZHAO H, LI J, ZHAO Q, et al. (2024). Si-based anodes: Advances and challenges in Li-ion batteries for enhanced stability, Electrochemical Energy Reviews, 7(1): 11.

[14]. LI Y, LI Q, CHAI J, et al. (2023). Si-based anode lithium-ion batteries: A comprehensive review of recent progress, ACS Materials Letters, 5(11): 2948-2970.