1. Introduction

This research aims to study the impacts of perceived academic stress levels and mindsets on the personality trait development of neuroticism. Given that academic stress is closely related to our lives and mental well-beings-- especially for teenagers and young adults, and the academic performance of adolescents, this research is crucial for exploring the personality development during this critical developmental stage and addressing the existing gap.

1.1. Personality stability and change

Personality traits are enduring individual differences in thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that exhibit systematic rank order and mean-level changes across the life span[1]. Personality traits are most often studied using the Five-Factor personality trait model, also known as the Big Five model. The five broad traits are extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience. While personality traits are considered relatively stable across different situations and over time, some studies have shown that trait change can be associated with particular life stages and environmental factors, especially during young adulthood. For example, studies show that the mean level of conscientiousness first increases when adolescents enter young adulthood and then decreases when they continue to get older[2]. Similarly, environmental factors have been shown to relate to personality change over time. For instance, adversity in life can potentially increase emotionality and decrease agreeableness[3]; time demand and job control predict changes in neuroticism, extroversion, and conscientiousness by shaping job stress positively and negatively[4].

1.2. Stress and perception of stress

Stress as a common experience that affects people across the world can not only affect individuals’ mental well-being, but might also have profound impacts on personality development, especially on aspects involving negative aspects such as pessimism and neuroticism[5]. Previous studies have found that the effects of stressors on individuals’ experiences are influenced by individuals’ stress appraisals. That is to say that two individuals can yield different stress perceptions and responses regarding the same stressful event. A previous study investigating the effect of graduating from school on personality trait change found that subjective perception of events has a significant impact on personality change for emotional stability. To be more specific, participants who appraised graduating from school more negatively exhibited a diminished increase in emotional stability than individuals who had appraised it more positively[6]. This directs my research into the impacts of the individual’s perception of stress on personality development.

1.3. The moderating role of mindset

As mentioned above, individuals’ stress appraisals vary, contributing to stronger or weaker effects of stressors on individuals. People’s cognitive or internal belief systems, such as beliefs, attitudes, expectations, and goals, which account for how people sense and perceive environmental stimuli and solve problems, are hypothesized to contribute to this variation. In the study that investigates the effect of graduating from school on personality trait change, mindsets have been found to be a moderator for extraversion[6]. Similarly, my study delves into the potential moderating effects of mindsets(growth mindset v.s. fixed mindset) on the relationship between perceived academic stress level and neuroticism.

1.4. Late adolescence and academic stress

Adolescence is the period of transition between childhood and adulthood. There are many significant changes taking place during this time: physical, sexual, cognitive, social, and emotional changes; those changes are critical for teenagers to enter adulthood. Adolescence is divided into three phases: early adolescence(Ages 10 to 13), middle adolescence (Ages 14 to 17), and Late Adolescents (Ages 18-21). As the identity-crisis stage of development, adolescence is marked by sharp biological and psychological changes, including elevated stress[7]. Specifically, adolescence is rife with academic stress, which is defined as psychological and emotional strain experienced by students related to academic demands from schools, exams, and assignments... Students in late adolescence (ages 18-21), namely from high school seniors to college, tend to feel the most intense academic stress due to graduation or increasing difficulty in academic tasks.

However, there is a gap in understanding the specific impacts of perceived academic stress level and mindsets on personality development of neuroticism in late adolescence.

1.5. The present study

Taken together, this research will delve into personality development by investigating how perceived academic stress influences the development of personality trait of neuroticism in the key developmental stage of late adolescence, which is crucial for filling up the existing gap. The findings of this research will highlight the importance of mental well-being in adolescents. Raising awareness of how stress perception and mindsets affect development could lead to more effective mental health interventions from parents and educators. Additionally, by focusing on how we interpret stress and how that interpretation can affect our futures, we can be more aware of the power of our internal belief systems and include positive stress interpretations and coping strategies.

Based on prior findings, we constructed two hypotheses. First, perceived academic stress levels can influence the development of trait neuroticism. Specifically, higher levels of perceived academic stress will correlate with increased neuroticism. Second, mindsets moderate the relationship between perceived academic stress and neuroticism. In particular, people with fixed mindsets will experience a greater increase in neuroticism while people with growth mindsets will experience a lesser increase in neuroticism.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

352 high school seniors (age 18) from a typical public school in Qingdao, China will be recruited as participants in this study. Half of them will be males, and half of them will be females. (Sensitivity analyses revealed that with N = 352, assuming alpha = 0.05, and a two-tailed test, we can detect an effect of d = .3 with 80% statistical power.) I will use a questionnaire to generally explore the basic family backgrounds, financial situations, and academic abilities and academic grades of the potential participants, trying to make their past family and education experiences and current situations at least at similar levels to minimize the impact of other confounding factors.

2.2. Designs and procedures

I plan to conduct a longitudinal study, where measurements will be taken out at two different time spots. Each participant will complete three questionnaires to measure their perceived academic stress level, mindsets, and neuroticism level, first at the start of the academic year, and again at the end of the year.

2.3. Measures and materials

Three questionnaires will be employed in this study:

First, The Perceptions of Academic Stress Scale (PAS)[8], which was developed to measure perceptions of academic stress and its sources will be used to measure the perceived academic stress level of participants at two time spots.

Second, Dweck's Mindset Instrument(DMI)[9] will be used to evaluate people’s mindsets. By asking the participants to rate the degree that they agree with the statement like “No matter who you are, you can significantly change your intelligence level,” DMI diagnoses whether an individual have a relative growth or fixed mindset.

Third, the Big Five subscale of neuroticism will be used to measure the levels of neuroticism of participants and their change.

To further improve data quality, I plan to set up an attention check question in one questionnaire by asking “Did you work conscientiously on the test?”. After data is collected, I plan to exclude the participants who show no variability in their responses (suggesting not reading the questions carefully or taking the survey seriously) and those who fail the attention check question.

2.4. Analyses

The data will be analyzed using a paired t-test to test the correlation between the perceived academic stress level and change in neuroticism. Then, I will add an interaction term between perceived academic stress level and change in neuroticism and conduct a moderated regression analysis to test for a moderating role of mindsets. All analyses will be carried out in R.

3. Results

I expect to find that the results are in line with our hypotheses:

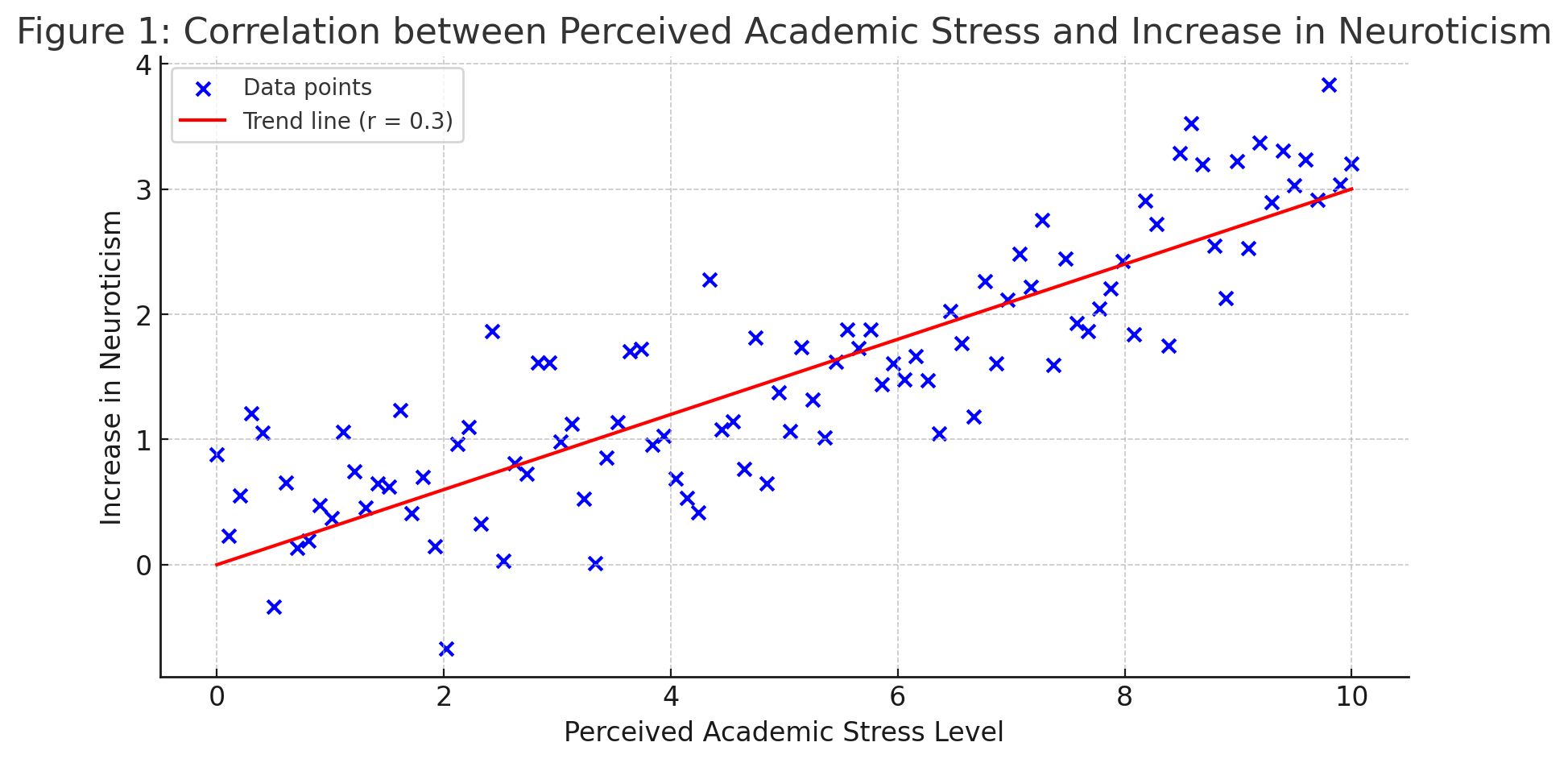

First, perceived academic stress level influences the development of trait neuroticism and higher levels of perceived academic stress will correlate with increased neuroticism. See Figure 1.

Second, mindsets moderate the relationship between perceived academic stress and neuroticism: people with fixed mindsets will experience a greater increase in neuroticism while people with growth mindsets will experience a lesser increase in neuroticism. See Figure 2.

4. General discussion

The purpose of this study is to investigate the impacts of perceived academic stress levels and people’s internal dispositions like the mindset on personality trait change. The predicted results that align with our hypotheses can be interpreted by the following:

1. Stress can significantly affect people’s mental health by evoking anxiety-related negative emotions. Studies have shown that chronic stress can disrupt brain chemistry, affecting areas associated with emotional feedback and potentially reinforcing people’s negative thought patterns, which in the long term increases their neuroticism levels.

2. A growth mindset can be considered a predictor of psychological resilience[10]. People with growth mindsets often believe situations are changeable and are more likely to regard stress as beneficial. They tend to adopt more positive stress-coping strategies, which leads to stable emotions and presumably a lesser increase in neuroticism. Conversely, people with fixed mindsets tend to perceive stressors as more formidable and respond to them in negative ways. This in turn affects their mental well-being and emotional stability by promoting negative emotions, which potentially leads to a greater increase in neuroticism.

There exist alternative interpretations:

1. Perceived academic stress levels can potentially correlate with decreased neuroticism. Current literature has pointed out the positive effects of stress. Research has revealed that stress can foster personal growth, improve mental fortitude, and enhance individuals’ sense of meaning[11]. Moreover, as individuals cope with increased academic stress, changes can take place: they may change their ways of seeing themselves, the stressors, and the world. In response to these changes, one may consider the tests and assignments as opportunities for personal improvements, and treat them in a positive mood or mindset, which possibly leads to a decrease in neuroticism[3].

2. Perceived academic stress levels can have no correlation with neuroticism. Individuals can differ from each other significantly, in areas such as personality, stress coping strategy, and the availability of social support. These variations that lead to different potential results can cancel out the correlation. Furthermore, sample-related factors may contribute to this lack of correlation. For example, if the sample is not diversified enough with various age ranges, education backgrounds, nationalities, and social backgrounds, the findings may not be able to generalize to broader populations.

5. Limitations

The nature of the longitudinal study means that we can not identify a causal relationship between perceived academic stress levels and changes in neuroticism. Longitudinal studies allow us to observe trends and associations over time, but they cannot establish direct cause and effect.

Additionally, confounding variables cannot be completely eliminated. Since there are too many stressors except academic stress in life and it is not likely to rule out all of them in the study, we cannot guarantee that the results are exclusively attributable to academic stress. Other critical life events, divorce of parents, for example, may happen at the same time when perceived academic stress level goes up and leads to a change in neuroticism.

Furthermore, the existence of moderator adds complexity. Individual differences in stress-coping mechanisms, or social support networks may moderate the relationship between academic stress and neuroticism, complicating the interpretation of results. These factors make it challenging to isolate academic stress as the sole explanation for changes in neuroticism in a real-world, multifaceted context.

6. Conclusion

The findings of this study have important implications. Recognizing the relationship between perceived academic stress levels, mindsets, and neuroticism is essential for promoting mental well-being in adolescents. Raising awareness of how stress perception and mindsets affect development could lead to more effective mental health interventions from parents and educators. Additionally, by focusing on how we interpret stress and how that interpretation can affect our futures, we can be more aware of the power of our internal belief systems and include positive stress interpretations and coping strategies. Future studies should address the limitations mentioned above by studying a more diverse sample and different cultures and also screening out other possible confounding variables. Possible manipulations of academic stress levels and subjective perception to determine causal relationships should also be considered in future studies.

References

[1]. Costa, P. T., Jr, McCrae, R. R., & Löckenhoff, C. E. (2019). Personality across the life span. Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 423–448. https: //doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103244

[2]. Lucas, R. E., & Donnellan, M. B. (2011). Personality development across the life span: Longitudinal analyses with a national sample from Germany. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(4), 847–861. https: //doi.org/10.1037/a0024298

[3]. Rakhshani, A., & Furr, R. M. (2021). The reciprocal impacts of adversity and personality traits: A prospective longitudinal study of growth, change, and the power of personality. Journal of personality, 89(1), 50–67. https: //doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12541

[4]. Wu, C.-H. (2016). Personality change via work: A job demand–control model of Big Five personality changes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 92, 157–166. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.12.001

[5]. Shields, G. S., Toussaint, L. L., & Slavich, G. M. (2016). Stress-related changes in personality: A longitudinal study of perceived stress and trait pessimism. Journal of Research in Personality, 64, 61–68. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.07.008

[6]. De Vries, J. H., Spengler, M., Frintrup, A., & Mussel, P. (2021). Personality development in emerging adulthood: How the perception of life events and mindset affect personality trait change. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 671421. https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.671421

[7]. Koepke, S., & Denissen, J. J. A. (2012). Dynamics of identity development and separation–individuation in parent–child relationships during adolescence and emerging adulthood: A conceptual integration. Developmental Review, 32(1), 67–88. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2012.01.001

[8]. Bedewy, D., & Gabriel, A. (2015). Examining perceptions of academic stress and its sources among university students: The Perception of Academic Stress Scale. Health psychology open, 2(2), 2055102915596714. https: //doi.org/10.1177/2055102915596714

[9]. Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

[10]. Oshio, A., Taku, K., Hirano, M., & Saeed, G. (2018). Resilience and Big Five personality traits: A meta-analysis. Personality and individual differences, 127, 54-60.

[11]. Crum, A. J., Salovey, P., & Achor, S. (2013). Rethinking Stress: The Role of Mindsets in Determining the Stress Response. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(4), 716–733. https: //doi.org/10.1037/a0031201

Cite this article

Qu,X. (2025). The Impacts of Perceived Academic Stress Levels and Mindsets on the Personality Trait Development of Neuroticism. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,108,15-21.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Global Politics and Socio-Humanities

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Costa, P. T., Jr, McCrae, R. R., & Löckenhoff, C. E. (2019). Personality across the life span. Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 423–448. https: //doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103244

[2]. Lucas, R. E., & Donnellan, M. B. (2011). Personality development across the life span: Longitudinal analyses with a national sample from Germany. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(4), 847–861. https: //doi.org/10.1037/a0024298

[3]. Rakhshani, A., & Furr, R. M. (2021). The reciprocal impacts of adversity and personality traits: A prospective longitudinal study of growth, change, and the power of personality. Journal of personality, 89(1), 50–67. https: //doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12541

[4]. Wu, C.-H. (2016). Personality change via work: A job demand–control model of Big Five personality changes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 92, 157–166. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.12.001

[5]. Shields, G. S., Toussaint, L. L., & Slavich, G. M. (2016). Stress-related changes in personality: A longitudinal study of perceived stress and trait pessimism. Journal of Research in Personality, 64, 61–68. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.07.008

[6]. De Vries, J. H., Spengler, M., Frintrup, A., & Mussel, P. (2021). Personality development in emerging adulthood: How the perception of life events and mindset affect personality trait change. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 671421. https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.671421

[7]. Koepke, S., & Denissen, J. J. A. (2012). Dynamics of identity development and separation–individuation in parent–child relationships during adolescence and emerging adulthood: A conceptual integration. Developmental Review, 32(1), 67–88. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2012.01.001

[8]. Bedewy, D., & Gabriel, A. (2015). Examining perceptions of academic stress and its sources among university students: The Perception of Academic Stress Scale. Health psychology open, 2(2), 2055102915596714. https: //doi.org/10.1177/2055102915596714

[9]. Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

[10]. Oshio, A., Taku, K., Hirano, M., & Saeed, G. (2018). Resilience and Big Five personality traits: A meta-analysis. Personality and individual differences, 127, 54-60.

[11]. Crum, A. J., Salovey, P., & Achor, S. (2013). Rethinking Stress: The Role of Mindsets in Determining the Stress Response. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(4), 716–733. https: //doi.org/10.1037/a0031201