1. Introduction

Cities are becoming more crowded as their populations grow. The process of urbanization has also swallowed up the original natural ecosystem, and how much green space to build and how to allocate it has become a matter of human decision.

Whether in cities of the global South or the global North, there is an unequal distribution of urban green-space resources. Often, wealthier neighborhoods have access to more and better quality urban green spaces and parks. Conversely, lower-income and minority communities have fewer and lower-quality green space resources. However, in addressing this inequality, better living conditions exacerbate the gentrification of neighborhoods and the homelessness of low-income populations, and better resources keep flowing into the hands of higher-income groups. This is a paradoxical problem that makes it challenging to address the unequal distribution of public green-space resources in cities.

This paper will begin by clarifying what urban green space is and the benefits it provides to city dwellers. An explanation of the unequal distribution of urban green-space will follow this. The second half of this article will address this issue by exploring the deeper issues behind the unequal distribution of urban green-space, including Green Gentrification, Environmental Justice, and market-led urban planning and construction.

2. Urban Green-space

Before discussing the issue of urban green spaces, it is essential first to clarify what they are and what benefits they bring to the residents and the city’s ecology. Green space in urban areas is considered to have two interpretations [1]. The first concept refers to areas of plants or bodies of water in the landscape, typically forests, wilderness areas, or farmland, and this macroscopic understanding of green-space may be synonymous with natural landscapes or the antonym of urbanization [1]. The second interpretation of green-space refers to urban vegetation, including gardens, yards, urban forests, urban farms, and so on. Green-space under this interpretation can often be understood as a subset of public open space under the macro concept. The second interpretation of green-space refers to urban vegetation, including gardens, yards, urban forests, urban farms, and so on. Green-space under this interpretation can often be understood as a subset of public open space under the macro concept. Green space under this interpretation can often be understood as a subset of public open space under the macro concept, which embodies anthropocentric land use and requires perceived participation and planning[1]. The interpretation of “green space” used in this paper is the second one. It is the green space generated by the development and utilization of urban land centered on human interest.

2.1. Green-space to Improve the Urban Environment

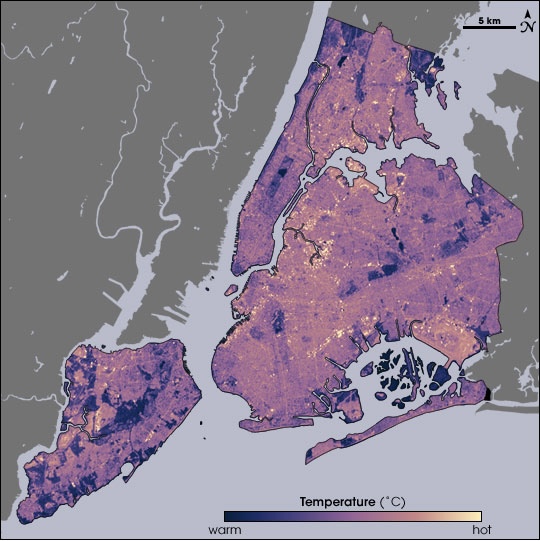

Given that human benefits are used as a starting point for discussing green spaces in cities, what benefits can green spaces bring to city residences? The first is the positive role that urban green-spaces play in the living environment of residents. Trees in urban green spaces can remove airborne pollutants to some extent [2]. According to an article called “Tree and forest effects on air quality and human health in the United States,” the amount of pollution removed by vegetation in urban and rural areas of the United States throughout 2010, as well as its economic and health value, was studied. The article points out that while vegetation in urban areas has a positive impact on air quality and human health, it harms the health of the people who live there. The article points out that although vegetation removed only 3.7% of the pollution in urban areas, the health and economic value of this pollution removal was much higher than in rural areas. 68.1% of the value came from urban areas [2]. This example proves that urban greenery can effectively purify the air, bring health value to city dwellers, and improve the urban living environment. Not only air pollution but there is also the Urban Heat Island Effect (UHIE) in cities due to the hardening of large areas of urban land, such as roads, buildings, parking lots, and so on. The materials (concrete, asphalt, steel) that are commonly used to construct roads, buildings, and parking lots have thermal bulk properties and surface radiation properties that are very different from those of natural land, which results in more heat being absorbed and retained by these construction materials [3]. Urban green spaces, on the other hand, can effectively mitigate the urban heat island effect, with trees and plants effectively lowering the average temperature of the surrounding area through shading and evaporation [4]. Here are two images of data from NASA. One is an infrared satellite map showing one of the hottest days in 2002 in New York, USA (Fig.1), and the other is a citywide map of vegetation cover in New York (Fig.2) [5]. These two maps directly reflect that the higher the density of vegetation, the lower the temperature.

Figure 1. Thermal infrared satellite data measured by NASA’s Landsat Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus on August 14, 2002 [5]

Figure 2. Vegetation data of New York City, collected by Landsat.[5]

2.2. Green-space Provides Health Value to Residents

Urban green spaces also provide benefits to city residents in terms of health. A study of the relationship between green space and patients demonstrated the positive effects of green space on human health. This study investigated the recovery records of patients in suburban Pennsylvania hospitals after cholecystectomy from 1972 to 1981, and the 23 patients in the study whose ward windows faced the wall recovered more quickly physically from their illnesses compared to the 23 patients whose ward windows had access to green landscapes [6]. Green spaces are not only associated with patients in a more abstract way, but green spaces such as parks are often used as places for people to engage in physical activity, and adequate physical activity is often associated with increased health and reduced incidence of chronic diseases. A study utilizing GIS to explore the presence and accessibility of green space and mortality rates in Florida demonstrated a significant relationship between the accessibility of green space and local mortality rates from cardiovascular disease. For example, it was found that counties with more people with access to green space had lower mortality rates [7]. This study not only demonstrates the vital link between green space and the health of residents but also points out that the accessibility of green space also dramatically influences the extent to which it can bring health value to residents.

Next, using examples from the United States and Mexico, this paper will address and exemplify the inequality of green space in cities and explore the deeper reasons behind it.

3. Environmental Injustice in Urban Green-Spaces

The concept of urban green space has been described above, and the importance of urban green space has been demonstrated from two aspects (environment and health). In addition, it concludes by emphasizing the importance of rational distribution and adequate accessibility for urban green space to be used to its advantage.

It has been shown that a rational and equitable distribution of urban green space can significantly improve social and individual well-being in cities [8]. However, inequalities in urban green space are widespread. Such inequalities threaten improvements in the well-being of urban residents. Inequalities in urban ecological services and green space per capita have become substantial urban environmental justice and public health issues [9].

However, this is what leads to the uneven distribution of green space as well as poor accessibility. It could be a historical legacy of the urban development process. There may also be factors related to the income and education levels of urban residents, as well as racial differences.

3.1. Income and Educational Attainment

This factor leads to the uneven distribution of green space and poor accessibility. It could be a historical legacy of the urban development process. However, this inequity may be related to factors such as the income and education level of urban residents. A study conducted by Columbia University researchers delved into how park and green space use varies by class, education, race, and other key variables. They selected ten cities in the U.S. for their study, representing U.S. cities with different population densities, population sizes, housing ages, average temperatures, precipitation, and socioeconomic characteristics. This study found that green inequality in cities strongly correlates with educational income levels (the lower the income and education levels, the worse the enjoyment of urban ecological services) [10]. However, certain variables are involved, with income levels in cities with lower per capita incomes playing a more significant role in the statistics. In comparison, race and ethnicity become more intuitive variables in cities with higher incomes [10].

3.2. Marginalization

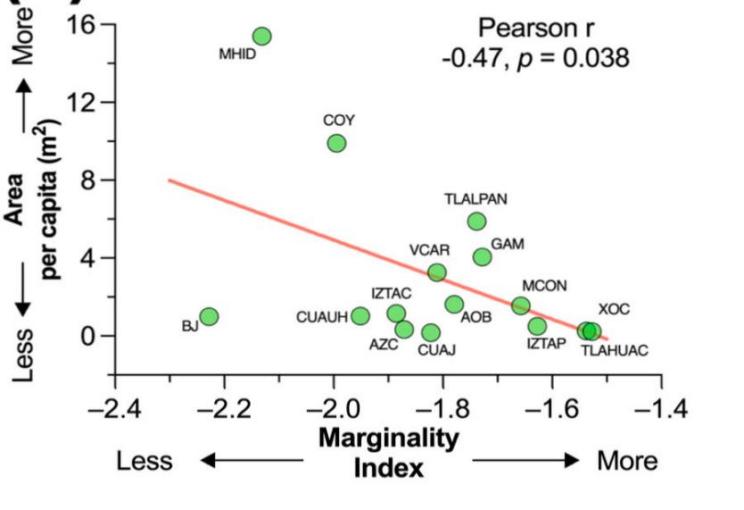

Another study using Mexico City as a research subject explored the link between the accessibility of green space in the city and the marginalization of social groups. This study explores another possibility contributing to inequality in urban green space: the marginalization of some groups in the city. This study counts the area of green space enjoyed per capita in 15 districts of Mexico City, as well as the marginalization index. It explores the relationship between green space allocation and marginalization by comparing these two data (Fig. 3) [11]. The graphs show that the higher the marginalization index, the lower the green space enjoyment per capita, proving that the marginalization of some social groups in the city at the economic and geographic level is one of the factors contributing to the inequality of green spaces.

Figure 3. Association between the marginality indices and the area per capita of Urban Green Spaces for the municipalities of Mexico City

3.3. Green-Gentrification

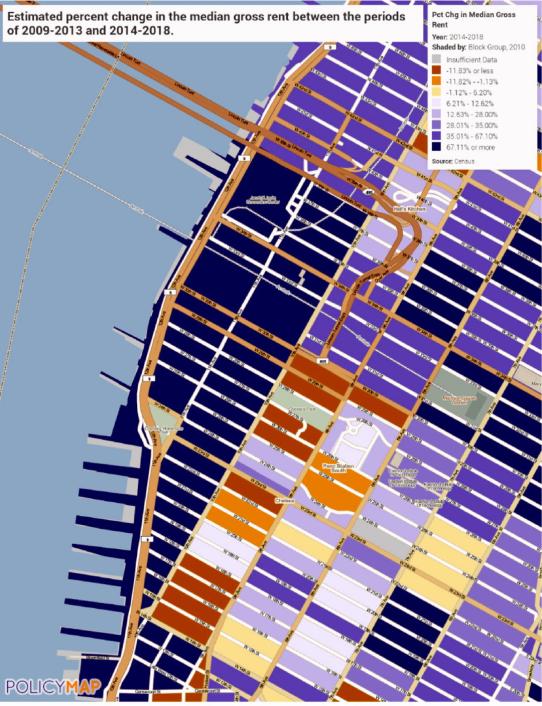

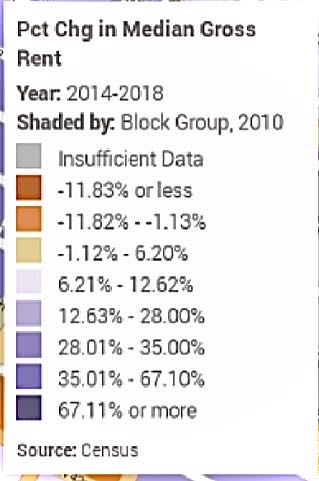

However, it is not only differences in income and educational attainment and urban marginalization that lead to inequality in ecological services in cities. The government’s efforts to improve community green spaces have led to a significant reduction in the inclusiveness of pre-existing communities, resulting in the further marginalization of some groups (e.g., low-income, ethnic minorities, etc.). This phenomenon is known as “Green-Gentrification.” It is a subset of gentrification. Moreover, this process is primarily the result of government and market-led land development and community upgrading. One of the best examples of green renovation took place in Manhattan with the “High Line” project. The project transformed abandoned railroad tracks into a beautiful urban park, providing valuable outdoor recreational space for city residents and increasing the attractiveness of the surrounding real estate. However, as the project progressed, housing prices in the neighborhood rose dramatically, and residents began to feel the pressure of rising rents and prices. As can be seen in Figure 4, housing prices in the High Line Park neighborhood have increased by 67% or more between 2014 and 2018 [12]. This data and the appreciation that High Line Park has brought to the surrounding housing stock is a visual representation of “green gentrification.” However, this phenomenon is not an exception. In the book “The Politics of Park Design-A history of Urban Parks in America”, it is noted that many large park projects, including New York’s Central Park, have been designed as opportunities for land value and development [13].

Figure 4. Percentage Change in Median Rent-NYC High Line area [12]

The phenomenon of “green-gentrification” makes it a “paradox” to improve poorly served communities by building more green space. Green-gentrification makes it impossible for people needing better ecological services to live in a neighborhood with a sizable amount of green space. A positive view of sustainability and market-led practice of utilizing the development of green space to enhance land value keeps low-income people marginalized from green communities. Therefore, when exploring solutions for the rational allocation of urban green space, we should consider how to counteract or avoid the factors and conditions that give rise to “green-gentrification”.

4. Avoid “Green-Gentrification”

In addressing this paradox of green space, what are how inequalities in urban green space can be ameliorated while at the same time avoiding the re-emergence of the phenomenon of “green gentrification.” The key is to ensure the affordability of community housing and to make communities greener but less “gentrified.”

4.1. Affordable Housing

The development of affordable housing is one of the most direct and effective measures to guarantee housing security for low-income groups, and such housing is guaranteed to be affordable through active government intervention in the price of rent and ownership of their homes. According to the definition of housing affordability provided by the City of Toronto, the monthly cost of housing, whether rental or ownership, is no more than 30% of the monthly household income at the target income level (defined by what percentile household income is below). An article called “Strategies to Preserve and Build Affordable Housing Near Green Amenities and Urban Trails” explores the potential of installing affordable housing to avoid evictions of community residents due to green space construction and concludes by suggesting that “planning for housing affordability as early as possible in new green amenities construction early planning for housing affordability will help avoid housing instability for residents of affected communities.” [14].

4.2. “Just Green Enough”

A strategy identified in fieldwork in Brooklyn, Greenpoint, is called “Just Green Enough.” This strategy offers a new way of thinking to avoid the phenomenon of green space development leading to gentrification. The “Green Enough” strategy focuses on social justice and environmental goals defined by the local community, targeting those most negatively impacted by environmental inconvenience, and works to keep them in place to enjoy any environmental improvements [15]. In the case of Green Point, the goal of the “Just Green Enough” strategy is to clean up toxic creeks and develop green space along the creeks in the vicinity of former working-class populations and industrial areas. This approach to green space development works closely with residents to explore the needs of local communities and residents for green space. It involves residents in developing the green space rather than development and planning based on value-added market demand [15]. This strategy gives another idea for solving the problem of gentrification and inequality of green spaces. The development of these “Just Green Enough” green spaces may not be as glamorous as the green spaces in some upscale urban neighborhoods, but they are green enough and very environmentally friendly.

5. Conclusion

Urban green spaces offer immense value to city residents, spanning both environmental and health benefits. However, because of their intrinsic value, as cities develop green spaces, these areas inadvertently become catalysts for gentrification. This is due both to the allure they offer to the affluent and the leverage they give to land developers to increase property values. Later in this paper, various solutions to combat green gentrification will be discussed, including promoting affordable housing and the “Just Green Enough” approach. Nonetheless, implementing these strategies requires concerted collaboration between governments, community groups, and residents. In conclusion, while addressing inequalities in green space distribution is challenging, the ultimate goal is clear: to promote environmental justice, social equity, and public health in urban settings.

References

[1]. Taylor, L., & Hochuli, D. F. (2017). Defining green-space: Multiple uses across multiple disciplines. Landscape and Urban Planning, 158, 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.09.024

[2]. Nowak, D. J., Hirabayashi, S., Bodine, A., & Greenfield, E. (2014). Tree and forest effects on air quality and human health in the United States. Environmental Pollution, 193, 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2014.05.028

[3]. Oke, T. R. (1982). The energetic basis of the urban heat island. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 108(455), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.49710845502

[4]. Zupancic, T., Westmacott, C., & Bulthuis, M. (2015, March). The impact of green space on heat and air pollution in urban communities. David Suzuki Foundation. https://davidsuzuki.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/impact-green-space-heat-air-pollution-urban-communities.pdf

[5]. NASA. (2006, August 2). Beating the heat in the world’s Big Cities. NASA. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/GreenRoof

[6]. Ulrich, R. S. (1984). View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science, 224(4647), 420–421. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.6143402

[7]. Coutts, C., Horner, M., & Chapin, T. (2010). Using geographical information system to model the effects of Green Space Accessibility on mortality in Florida. Geocarto International, 25(6), 471–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/10106049.2010.505302

[8]. Chalmin-Pui, L. S., Griffiths, A., Roe, J., Heaton, T., & Cameron, R. (2021). Why garden? – attitudes and the perceived health benefits of home gardening. Cities, 112, 103118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103118

[9]. Chen, Y., Ge, Y., Yang, G., Wu, Z., Du, Y., Mao, F., Liu, S., Xu, R., Qu, Z., Xu, B., & Chang, J. (2022). Inequalities of urban green space area and ecosystem services along urban center-edge gradients. Landscape and Urban Planning, 217, 104266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104266

[10]. Nesbitt, L., Meitner, M. J., Girling, C., Sheppard, S. R. J., & Lu, Y. (2019). WHO has access to urban vegetation? A spatial analysis of distributional green equity in 10 U.S. cities. Landscape and Urban Planning, 181, 51–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.08.007

[11]. Ayala-Azcarraga, C., Diaz, D., Fernandez, T., Cordova-Tapia, F., & Zambrano, L. (2023). Uneven distribution of urban green spaces in relation to marginalization in Mexico City. Sustainability, 15(16), 12652. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612652

[12]. Jo Black, K., & Richards, M. (2020). Eco-gentrification and who benefits from Urban Green Amenities: NYC’s high line. Landscape and Urban Planning, 204, 103900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103900

[13]. Cranz, G. (1982). The Politics of Park Design. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/5469.001.0001

[14]. McComas, M., & Lefkovitz, J. (2022, February). Strategies to preserve and build affordable housing near green ... Johns Hopkins-21st Century Cities Initiative. https://21cc.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/affordable-housing-near-green-amenities-and-urban-trails.pdf

[15]. McCreary, T. (2020). Just green enough: Urban development and environmental gentrification edited by Winifredcurran and Trinahamilton, Routledge, New York, 2018, 248 pp., hardback $208.80 (ISBN 978‐1138713796). Canadian Geographies / Géographies Canadiennes, 64(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12621

Cite this article

Chang,C. (2024). Urban Green-Space: Environmental Justice & Green Gentrification. Applied and Computational Engineering,61,193-199.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Materials Chemistry and Environmental Engineering

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Taylor, L., & Hochuli, D. F. (2017). Defining green-space: Multiple uses across multiple disciplines. Landscape and Urban Planning, 158, 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.09.024

[2]. Nowak, D. J., Hirabayashi, S., Bodine, A., & Greenfield, E. (2014). Tree and forest effects on air quality and human health in the United States. Environmental Pollution, 193, 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2014.05.028

[3]. Oke, T. R. (1982). The energetic basis of the urban heat island. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 108(455), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.49710845502

[4]. Zupancic, T., Westmacott, C., & Bulthuis, M. (2015, March). The impact of green space on heat and air pollution in urban communities. David Suzuki Foundation. https://davidsuzuki.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/impact-green-space-heat-air-pollution-urban-communities.pdf

[5]. NASA. (2006, August 2). Beating the heat in the world’s Big Cities. NASA. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/GreenRoof

[6]. Ulrich, R. S. (1984). View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science, 224(4647), 420–421. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.6143402

[7]. Coutts, C., Horner, M., & Chapin, T. (2010). Using geographical information system to model the effects of Green Space Accessibility on mortality in Florida. Geocarto International, 25(6), 471–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/10106049.2010.505302

[8]. Chalmin-Pui, L. S., Griffiths, A., Roe, J., Heaton, T., & Cameron, R. (2021). Why garden? – attitudes and the perceived health benefits of home gardening. Cities, 112, 103118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103118

[9]. Chen, Y., Ge, Y., Yang, G., Wu, Z., Du, Y., Mao, F., Liu, S., Xu, R., Qu, Z., Xu, B., & Chang, J. (2022). Inequalities of urban green space area and ecosystem services along urban center-edge gradients. Landscape and Urban Planning, 217, 104266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104266

[10]. Nesbitt, L., Meitner, M. J., Girling, C., Sheppard, S. R. J., & Lu, Y. (2019). WHO has access to urban vegetation? A spatial analysis of distributional green equity in 10 U.S. cities. Landscape and Urban Planning, 181, 51–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.08.007

[11]. Ayala-Azcarraga, C., Diaz, D., Fernandez, T., Cordova-Tapia, F., & Zambrano, L. (2023). Uneven distribution of urban green spaces in relation to marginalization in Mexico City. Sustainability, 15(16), 12652. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612652

[12]. Jo Black, K., & Richards, M. (2020). Eco-gentrification and who benefits from Urban Green Amenities: NYC’s high line. Landscape and Urban Planning, 204, 103900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103900

[13]. Cranz, G. (1982). The Politics of Park Design. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/5469.001.0001

[14]. McComas, M., & Lefkovitz, J. (2022, February). Strategies to preserve and build affordable housing near green ... Johns Hopkins-21st Century Cities Initiative. https://21cc.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/affordable-housing-near-green-amenities-and-urban-trails.pdf

[15]. McCreary, T. (2020). Just green enough: Urban development and environmental gentrification edited by Winifredcurran and Trinahamilton, Routledge, New York, 2018, 248 pp., hardback $208.80 (ISBN 978‐1138713796). Canadian Geographies / Géographies Canadiennes, 64(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12621