1.Introduction

In recent years, social media use has changed dramatically [1]. Over the past decade, the number of people worldwide adopting and integrating social media into their daily lives has grown exponentially [2]. Social media platforms allow users to view messages initiated by others and produce and disseminate content by themselves, enabling individuals to share their stories and feelings instantly [3]. Social media platforms are increasingly crucial in learning cyber communication and self-expression. At the same time, users can turn to a wide variety of contacts through social media for social support needs [4,5].

Chinese social media platforms such as Sina Weibo, WeChat, and Douyin have become increasingly popular, attracting many users in and outside of China. The development of social media in China may be influenced by the Chinese social environment, including cultural and other factors, and different social media platforms are used to meet users' diverse needs. For instance, Sina Weibo is a prominent Chinese micro-blogging platform often referred to as "China's Twitter", which serves as a vital source of entertainment, news, and communication in China by sharing short messages, images, and videos while fostering online communities; Zhihu is a platform built initially for knowledge contribution, which encourages users to publish user-generated questions and answers in depth and can provide users with reliable and professional information on a specific area or topic [6]. Red (Xiaohongshu) is an integrated shopping and community social media platform in China that allows users to explore and post their life experiences and product reviews, most frequently related to beauty and travel [7].

While much of the communication on social media is positive and designed to entertain users, the growing popularity of social media has also brought a dark side to contact [8]. The rapid development of social media platforms enables people to communicate among different regions and cultures, while the anonymity of the network also weakens the moral bond of online users, which leads to massive cyber abuses [9]. In addition to "likes" and positive feedback, negative comments and offensive behaviors overshadow the online world of social media. Cyber abuse occurs through the network and other modern technology forms, encompassing a wide range of aggressive online activities [10]. This can be defined as repeated, deliberate acts of electronic aggression by a group or individual over a while against victims who cannot easily defend themselves [11]. Online abuse can pose many problems, including causing victims to suffer emotional, psychological, and even physical harm, creating a sense of fear and exclusion online, eroding trust in media platforms, poisoning public communication, and stimulating other extremism [12,13].

Severe cyber abuse happened on China's social media platforms, which has become a growing concern in recent years. Some malignant events occurred in China, such as the girl with pink hair dying of depression caused by online abuse, the suicide of an Internet celebrity after being overwhelmed by anti-fans, and so on. China has begun to take this phenomenon seriously and is mulling new regulations to address cyber abuse and bullying content, which puts forward related management measures and asks for timely solutions. In July 2023, the Cyberspace Administration of China, known as the country's top Internet regulator, launched several campaigns calling on online platforms and organizations to work together to focus on rectifying and improving the Internet environment and building a long-run institutional arrangement to combat cyber abuse [14]. It is a long and arduous task to control the cyber abuse phenomenon, which requires the joint efforts of all sides of society.

Considering the specific cyber environment of China, this study mainly focuses on the cyber abuse phenomenon of trolling, cyberstalking, body shaming, and slut shaming on social media. Trolling is the practice of organizations or individuals posting aggressive messages and acting deceitfully, destructively, or contemptuously in the Internet environment without manifest intention [15,16]. Cyberstalking uses text messaging, emails, and social media platforms to pursue, monitor, stalk, harass, or threaten another unsolicitedly. It uses the Internet to target victims, ranging from constant annoying contact to violent threats, and can escalate into trying to control an individual's behavior [10,17,18]. Body shaming is an action in which a person expresses unwanted, mostly negative appearance-related commentary on other people's bodies, which is a general term for more specific phenomena like fat-, weight-, or skinny-shaming [8]. Slut-shaming refers to condemning a person's behavior as acting outside of decency or morality. The victim's behavior may be entirely sexual, such as criticizing their promiscuity; it may only have sexual innuendo, such as charging a person for being too provocatively dressed, and women are the predominant targets [19-21].

Cyber abuse can cause dire consequences; the harm is actual and widespread online and offline. It can pollute cyberspace and inflict heavy mental pressure and psychological trauma on many. Understanding the prevalence of cyber abuse is significant for addressing more complex and nuanced issues, such as the reasons and primary forms, when it certifies, which network platform has nourished its development, its impact on victims and society, and how we can challenge it. Our study conducted an exploratory paper on online abuses and mainly focused on trolling, cyberstalking body shaming, and slut shaming on Chinese social media. The goal is to explore people's experiences of online abuse and understand the potential emotional or behavioral impact of these four types on victims. While attempting to have a deeper understanding of the phenomenon and learn more about Chinese national online conditions, we also hope to provide a potentially helpful perspective for network environment governance based on the findings of the four types of online abuse on China's social media.

2.Literature Review

Many studies have found that online abuses were widely spread and harmful, and people from different age groups and sexual orientations suffered from online activities of various kinds. Research conducted in Australia investigated online abuse as a severe problem for women and men of different ages [22]. In particular, some studies focused on the trend of online abuse growing among specific age groups, including teenagers, young adults, and older adults, and emphasized its severe impact on people. One study claimed that online abuse had intensively affected college students' daily routines [23]. Another study demonstrating relatively similar concern from teenagers' perspectives reported that a growing number of online abuse actions towards teenagers caused harmful effects on them [24].

Many studies have been done on populations worldwide, such as the USA, Australia, and Germany. One article claimed that online abuse had been a predominant problem across Australia [22]. One study focusing on women's perspectives stated that about 73.4% of women bloggers in Germany, Switzerland, the UK, and the USA had experienced negative cyber actions and comments during that time [25]. However, little research and studies were done on Chinese people's related patterns of online abuse.

Many studies took a deep vision into different categories of online abuse separately, such as trolling, body shaming, and slut shaming. Notably, some articles about trolling have clarified this term greatly, such as the book Online Trolling and its Perpetrators: Under the Cyberbridge [26]. According to this research, trolling can be identified as four behavioral types – serious trolling (not funny and ideologically motivated), humorous trolling, non-trolling severe behaviors, and humorous non-trolling.

Among the studies focusing on the categories of online abuse, trolling was the action mentioned most frequently. Trolling was becoming increasingly prevalent and visible in online communities. Nevertheless, there have been no studies that combined all kinds of online abuse actions and studied the relationship among them, such as trolling, cyberstalking, body-shaming, and slut-shaming. This research aims to replenish a better understanding of the relationship between different types of online abuse actions.

3.Research Question

3.1.Do people often suffer online abuses on Chinese social media?

3.2.Which types are the most common?

3.3.What are the potential impact of trolling, cyberstalking, body-shaming, and slut-shaming on social media in China?

4.Methodology

4.1.General Methods & Demographics

This study employed an online paper for data collection. One hundred fifty-two questionnaires were recovered, and 152 were valid.

The paper was conducted in July 2023 and lasted three days; all respondents were Chinese social media users. The questionnaires were distributed online through Chinese social media platforms, and the answers almost all came back from WeChat (98%). Before study participation, respondents were informed that the paper was entirely anonymous and the report's results were for academic purposes only. Besides, the article was voluntary, and respondents could freely withdraw from the study without providing reasons. After the respondents agreed to participate in the research, they completed the questionnaire consisting of five parts - basic information and related questions about their experience of Trolling, Stalking, Body shaming, and Slut shaming on social media.

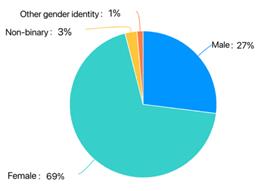

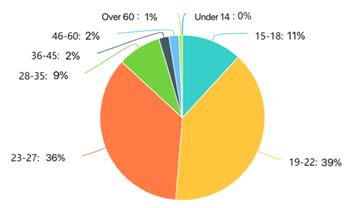

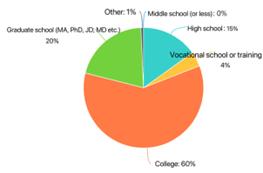

Among the 152 respondents, 69% (n=105) were female, and 27% (n=41) were male. Around 87% (n=132) of the respondents were between the ages of 15-27, and three-quarters (n=122) of them were college or higher degree graduates (Figure 1- Figure 3).

Figure 1: Gender distribution of respondents

Figure 2: Age distribution of respondents

Figure 3: Education distribution of respondents

Most of the sample reported that they were heterosexual (79%), 63% (n=95) were single, 78% (n=118) currently lived in first- and second-tier cities and the same proportion (78%) of them spent less than 3,500 yuan a month on entertainment activities such as shopping and watching movies. Approximately nine out of ten (n=135) of the participants spent more than one hour on social media daily.

4.2.Paper Questionnaire

The questionnaire was in Chinese. All the measures used in this paper were first translated from English into Chinese using the back-translation method, with wording modifications adapted to the Chinese context.

Participants were asked which social media platforms they mainly use and the primary forms of their social engagement behaviors on social media platforms (e.g., clicking "like," sending private messages, content creation, etc.).

Participants were asked whether they had been victims of the following cyber violence phenomenon in the past year: (1) Spam emails; (2) Online scams/fraud; (3) Hacking of your accounts; (4) Received hate speech; (5) Doxxing (public posting of your address or other identifying information); (6) Body-shaming attacks; (7) Slut-shaming attacks; (8) Trolling; (9) Cyberstalking; (10) Loss or theft of device.

In the second to fifth sections, respondents were first asked whether they had experienced this kind of online violence (Trolling, Cyberstalking, Body-shaming and Slut-shaming) respectively, and assessed the frequency 0 (“never”) to 6 (“daily”) of their experience, and then asked to use a 10-point scale to measure the influence for them, from 1 (Doesn’t bother me at all) to 5 (I dislike how I look) to 10 (I have suicidal thoughts). Respondents who had relevant experiences were asked to answer the following question:

Which of the following BEST describes any emotional or behavioral responses to being xxx (Select all that apply).

Emotional responses include: (1) nervous; (2) numb; (3) fearful; (4) depressed; (5) angry; (6) disgusted; (7) helpless; (8) disappointed; (9) anxious; (10) powerless; (11) guilty; (12) confusion;(13)overwhelmed.

Behavioral responses include: (1) I’m struggling with too much drinking; (2)My work/school performance has suffered; (3) I’m stressed; (4) I’ve withdrawn from people; (5) I’ve withdrawn from activities I previously enjoyed; (6) I have thoughts about self-harm/suicide; (7)I’m struggling with an eating disorder; (8)I’m struggling with substance abuse.

At the same time, the order of the options in the questionnaire was randomly set for the responses of emotions and behaviors and mutually exclusive with the possibility never affected to increase the internal consistency and reliability of the results.

At the end of the questionnaire, the respondents were rated on a 10-point scale for their body shape satisfaction (1=I hate my body, 5=I am not very satisfied with this body, but I can accept it, 10=I am proud of my body), higher scores indicate greater body shape satisfaction.

5.Findings & Discussion

5.1.Findings

The paper results showed that the top five popular Chinese social media platforms most used by participants were WeChat (89%), Red (66%), Bilibili (52%), Douyin (45%), and Sina Weibo (36%). In addition, several participants filled in QQ in the Other column (n=4).

Around 64% (n=98) of the respondents mainly participated on social media by clicking "like," 56% (n=85) only browsed content, 43% (n=65) primarily used social media to follow others, and 35% (n=53) actively commented on others.

According to the paper results, 59% (n=90) of the respondents said that they have not experienced any of the listed online abuse types, while the proportions who have encountered trolling, received spam emails, and received hate speech are the highest, 16% (n=24), 15% (n=23), and 13% (n=20) respectively. In addition, the proportion of people who have experienced trolling, cyberstalking, body shaming, and slut shaming attacks are around 16% (n=24), 7% (n=11), 3% (n=5), 2% (n=4), respectively.

The mean score of the study sample for the question about their body shape satisfaction was 7.14 (M=7.14).

5.2.Discussion

The paper identified four types of cyber abuse: trolling, cyberstalking, body-shaming, and slut-shaming. Among the participants, 62 reported experiencing cyber abuse in the past year, while 90 claimed they hadn't encountered any cyber abuse. Notably, trolling emerged as the most common type, affecting 39% of respondents. Cyberstalking, body-shaming, and slut-shaming affected 18%, 8%, and 7% of participants, respectively. Combining these types revealed exciting patterns, with some respondents experiencing multiple forms of cyber abuse, such as cyberstalking (10%), trolling combined with body shaming (3%), and others.

The paper ranked the most frequently used social media platforms, with WeChat, Red (Xiaohongshu), Bilibili, and Douyin (TikTok) topping the list. An analysis of gender differences revealed that trolling, hate speech, and scam emails were the most common types of cyber abuse across all genders and major platforms. Among male participants, trolling (5), hate speech (4), and scam emails (3) were prevalent. Similarly, among female participants, scam emails (18), trolling (17), and hate speech (15) were frequent. These findings indicate that trolling, hate speech, and scam emails are prevalent across genders and significant social media platforms.

The data collected from the paper provides compelling evidence that scam emails and hate speech can indeed be manifestations of trolling activities. Out of the total number of individuals who reported experiencing trolling in the past year (24), a significant proportion also encountered scam emails, hate speech, or a combination of all three abusive behaviors. The data shows that 17% of respondents experienced all three forms of cyber abuse simultaneously. Moreover, the occurrence of trolling together with email abuse was reported by 35% of participants, and 57% experienced exploring alongside hate speech. Additionally, 17% of respondents encountered both email abuse and hate speech. These figures suggest a strong association between trolling, scam emails, and hate speech, indicating that these abusive behaviors often co-occur in the online environment.

The paper's findings shed light on the psychological impact and severity of various types of cyber abuse experienced by the participants. When asked to rate the severity of their encounters on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 represents the lowest severity and 10 indicates the highest severity, it was observed that trolling and cyberstalking were the most prevalent form of cyber-abuse, with approximately 30% of respondents rating the severity at seven or above. Body shaming was placed with a severity of 7 or above by 23% of respondents. Regarding slut shaming, only 8% of individuals rated the severity at seven or above. These variations in severity ratings across different types of cyber abuse indicate the diverse psychological impacts that victims experience. Further research and support mechanisms are essential to understand the underlying reasons for the varying severity levels and to address the psychological toll cyber abuse takes on individuals in the digital age.

The paper also explored the relationship between the type of online activity and the frequency of cyber abuse experienced. Interestingly, the data indicated that active usage of social media, such as content creation (49%), commenting (47%), reposting (64%), and direct messaging (62%) were associated with higher rates of cyber-abuse compared to passive activities such as liking (43%), subscribing (50%), and simply scrolling (40%). Active social media usage may expose individuals to a higher risk of cyber abuse.

The findings overturn one of the original hypotheses that the more time an individual spends online, the more he will experience online abuse. Surprisingly, no significant correlation existed between spending more time online and experiencing more online abuse. Regardless of whether participants spent more than 5 hours, 3-5 hours, 1-3 hours, or about 1 hour online per day, the rates of cyberbullying remained relatively constant across all time categories. This suggests that the frequency of cyber abuse is not directly tied to the time spent online.

The results shed light on the prevalence and characteristics of different types of cyber abuse and the relationship between online activities and the frequency of cyber-abuses. The insights gained from this study can be instrumental in devising evidence-based strategies to tackle cyber abuse and promote safer online environments for all users.

6.Conclusion

While the study has provided valuable insights into the experiences of Chinese social media users regarding cyber abuse, it's essential to recognize some of the limitations of this survey.

One of the significant limitations is the lack of representativeness of age groups. The paper is designed to capture the opinions and behaviors of three age groups (15-18, 19-22, 23-27). Therefore, it may not accurately reflect the views and experiences of other age groups. This can result in a biased sample that may not represent the broader population. Additionally, specific topics or questions in the paper might be more relevant or applicable to particular age groups, leading to potential response discrepancies. For instance, questions regarding body shaming may be more practical to younger age groups as older age groups tend not to experience body shaming as much. Despite the limitation, the paper would still serve as a relatively representative image of online abuse because younger age groups tend to be the predominant target of online abuse.

The paper is conducted with 152 participants, a relatively small sample size. The article might not adequately represent the target population with the small size. Even though there have been new findings, there has not been enough data to prove that such a phenomenon fully represents the broader population, as subgroups of the target population might be neglected due to the small sample size. The precision and the accuracy of the paper are, therefore, limited.

Since the paper is conducted with participants, two significant limitations are present in the survey. Given the sensitive nature of the article (Trolling, Cyberstalking, Body-shaming, and Slut-shaming), participants may be hesitant to report personal experiences. Regarding whether participants have been perpetrators of online abuse, they might be inclined to present a better social image of themselves, even in an anonymous survey. Additionally, the paper relies mainly on self-reporting data from participants. This data type tends to be limited by the participant's ability to recall and report their past experiences accurately because memories can often be obscure or distorted. It would be possible that some participants have forgotten parts of their backgrounds or remembered them differently, which undermines the accuracy of the survey.

The paper is translated from English to Chinese, which causes certain limitations. Though efforts were made to modify the paper during the translation process, some nuances of the original language might inevitably have been lost. Differences in language and cultural context can impact the interpretation of questions and responses, leading to potential misunderstandings. This could affect the reliability and validity of the data collected.

The paper represents a single point in time (July 2023), providing a snapshot of the respondents' experiences when they responded to the survey. A longitudinal study would be more suitable for capturing changes and trends in online abuse over time.

Therefore, the findings suggested by the research are tentative, and should not be regarded as conclusive evidence of online abuse phenomena. Further research is needed to provide a more comprehensive understanding of online abuse.

7.Future Studies

Findings from the paper suggest that despite trolling being the most common form of cyber abuse, participants didn't frequently report their encounters with trolling activities. None of the 152 participants who responded to the paper specified their detailed experience of trolling. In contrast, some participants shared their experiences with cyberstalking, body-shaming, and slut-shaming. This phenomenon might be due to trivializing trolling activities for self-protection or the assumption that trolling content is widespread and not worth mentioning. The phenomenon can be explained by the "Online Disinhibition Effect" and the Spiral of Silence Theory.

The Online Disinhibition Effect suggests that people can form “dissociative imaginations” that “split or dissociate online fiction from offline facts” [27]. The same dissociation process likely happened during people's experience of trolling. As people receive trolling activity online, they dissociate their online self from their real-world self, desensitizing the training. People who suffer from trolling are trying to protect themselves by perceiving trolling as less shocking or harmful than it is. Individuals may not fully recognize the harm caused by such behavior, so they tend to underreport these activities.

The Spiral of Silence Theory posits that "to an individual, not isolating himself is more important than his judgment" [28]. In the context of online trolling, individuals might be hesitant to report trolling activities because they believe that such behavior is prevalent and accepted in the online environment. They may fear being ridiculed or dismissed if they speak up. This fear of social repercussions can lead to a reluctance to report trolling incidents, contributing to the underreporting phenomenon observed in the survey.

It is important to note that these are theoretical explanations, and the actual reasons for underreporting trolling incidents may vary. To gain a deeper understanding of this phenomenon, further research using qualitative methods, such as interviews, can be done to help capture participants' perspectives and motivations behind underreporting.

Findings from the paper also suggest a close association between scam emails, hate speech, and trolling activities. The results indicate a possibility that scam emails and hate speech can be manifestations of trolling activities.

Previous research has identified similar characteristics between trolling and scam emails and trolling and hate speech. In "Trolling in Asynchronous Computer-Mediated Communication: From User Discussions to Academic Definitions” (2010), Hardaker investigated trolling behaviors in asynchronous computer-mediated communication (CMC). He found that trolling behaviors can be defined through four dimensions: “deception, aggression, disruption, and success” [29]. In recorded discussions of trolling provided by Hardaker, one remark suggests that "comments come with only invective and insult and contain no content whatsoever," which is within the definition of trolling [29]. This definition of trolling in the "aggression" dimension closely resembles the commonsensical definition of hate speech in its aggression and intention to insult. Moreover, another example states that "While it's certainly possible this is a real email exchange, it would be a good idea to try to track down B and verify that this is a real person - not a troll" [29]. This discussion implies that scam emails are considered part of trolling activities, specifically in the "deceptive" dimension.

Even though this research provides data to support the assumption that hate speech and scam emails are manifestations of trolling activities, this conclusion is not definitive as the paper's sampling size is insufficient to suggest any conclusive result. Future research could conduct large-scale surveys or experiments to quantitatively measure the prevalence and patterns of trolling behaviors, scam emails, and hate speech across different online platforms and user groups. This would provide more robust data to identify correlations and potential causal relationships between these activities.

Acknowledgment

Qian Zhang, Qinxuan Chen, and Xinrong Gu contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors.

References

[1]. Rieger, D., & Klimmt, C. (2019). The daily dose of digital inspiration: A multi-method exploration of meaningful communication in social media. New Media & Society, 21(1), 97-118.

[2]. Chan, M., Lee, F. L., & Chen, H. T. (2021). Examining the roles of multi-platform social media news use, engagement, and connections with news organizations and journalists on news literacy: A comparison of seven democracies. Digital Journalism, 9(5), 571-588.

[3]. Choi, M., & Toma, C. L. (2014). Social sharing through interpersonal media: Patterns and effects on emotional well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 530e541.

[4]. Vitak, J., & Ellison, N. B. (2012). 'There's a network out there you might as well tap': Exploring the benefits of and barriers to exchanging informational and support-based resources on Facebook. New Media & Society, 15, 243e259

[5]. Jaidka, K. (2022). Cross-platform-and subgroup-differences in the well-being effects of Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook in the United States. Scientific reports, 12(1), 3271.

[6]. Li, J., & Zheng, H. (2020). Coverage of HPV-related information on Chinese social media: A content analysis of articles in Zhihu. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 16(10), 2548-2554.

[7]. Tang, Shiyi (2022). "How to Grow Your Business in Xiaohongshu - GPI Translations Blog". Globalization Partners International. Retrieved 2023-07-07.

[8]. Schlüter, C., Kraag, G., & Schmidt, J. (2021). Body shaming: an exploratory study on its definition and classification. International journal of bullying prevention, 1-12.

[9]. Zhang, P., Gao, Y., & Chen, S. (2019). Detect Chinese cyber bullying by analyzing user behaviors and language patterns. In 2019 3rd International Symposium on Autonomous Systems (ISAS) (pp. 370-375). IEEE.

[10]. Mishna, F., McLuckie, A., & Saini, M. (2009). Real-world dangers in an online reality: A qualitative study examining online relationships and cyber abuse. Social Work Research, 33(2), 107-118.

[11]. Smith, P. K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S., & Tippett, N. (2008). Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 49(4), 376-385.

[12]. Eatwell, R. (2006). Community cohesion and cumulative extremism in contemporary Britain. The Political Quarterly, 77(2), 204-216.

[13]. Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2007). Offline consequences of online victimization: School violence and delinquency. Journal of school violence, 6(3), 89-112.

[14]. Office of the Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission (2023). Guojia Hulianwang Xinxi Bangongshi guanyu Wangluo baoli xinxi zhili guiding (zhengqiu yijian gao) Gongkai zhengqiu yijian de tongzhi [Notice of the Cyberspace Administration of China on the Public solicitation of comments on the Provisions on Cyber Violence Information Governance (Draft for Comment)] Available at: http://www.cac.gov.cn/2023-07/07/c_1690295996362667.htm (Accessed: 25 July 2023).

[15]. Buckels, E. E., Trapnell, P. D., & Paulhus, D. L. (2014). Trolls just want to have fun. Personality and Individual Differences, 67, 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.016

[16]. Lumsden, K., & Morgan, H. (2017). Media framing of trolling and online abuse: Silencing strategies, symbolic violence, and victim blaming. Feminist Media Studies, 17(6), 926–940. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2017.1316755

[17]. Philips, F., & Morrissey, G. (2004). Cyberstalking and cyberpredators: A threat to safe sexuality on the Internet. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 10, 66-79.

[18]. Belknap, J., Chu, A. T., & DePrince, A. P. (2011). The roles of phones and computers in threatening and abusing women victims of male intimate partner abuse. Duke J. Gender L. & Pol'y, 19, 373.

[19]. Gong, L., & Hoffman, A. (2012). Sexting and slut-shaming: Why prosecution of teen self-sexters harms women. Georgetown Journal of Gender and the Law, 13(2), 577-590.

[20]. Poole, E. (2013). Hey girls, did you know: Slut-shaming on the internet needs to stop. USFL Rev., 48, 221.

[21]. Tanenbaum, L. (2015). I am not a slut: Slut-shaming in the age of the Internet. Harper Perennial.

[22]. Lee, C. (2022). Online abuse: Problematic for all Australians. Journal of Criminological Research, Policy and Practice. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JCRPP-02-2022-0006/full/html

[23]. Megan, L., & Judy, K. (2012). Online harassment among college students. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1369118X.2012.674959

[24]. Sengupta, A., & Chaudhuri, A. (2010). Are social networking sites a source of online harassment for teens? evidence from paper data. Children and Youth Services Review. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0190740910003208

[25]. Eckert, S. (2017). Fighting for recognition: Online abuse of women bloggers in Germany ... https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1461444816688457

[26]. Rodwell, E. (2019). Online trolling and its perpetrators: Under the cyberbridge. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1461444819859894

[27]. Suler, J. (2004). The Online Disinhibition Effect. Cyberpsychology & behavior : the impact of the Internet, multimedia and virtual reality on behavior and society. 7. 321-6. 10.1089/1094931041291295.

[28]. Noelle-Neumann, E. (1974). The Spiral of Silence a Theory of Public Opinion, Journal of Communication, Volume 24, Issue 2, Pages 43–51, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1974.tb00367.x

[29]. Hardaker, C. (2010). Trolling in asynchronous computer-mediated communication: From user discussions to academic definitions. UCLan. https://clok.uclan.ac.uk/4980/

Cite this article

Zhang,Q.;Chen,Q.;Gu,X. (2024). Trolling, Cyberstalking, Body-shaming, Slut-shaming – A Study on Online Abuses of Social Media. Communications in Humanities Research,28,232-241.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Global Politics and Socio-Humanities

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Rieger, D., & Klimmt, C. (2019). The daily dose of digital inspiration: A multi-method exploration of meaningful communication in social media. New Media & Society, 21(1), 97-118.

[2]. Chan, M., Lee, F. L., & Chen, H. T. (2021). Examining the roles of multi-platform social media news use, engagement, and connections with news organizations and journalists on news literacy: A comparison of seven democracies. Digital Journalism, 9(5), 571-588.

[3]. Choi, M., & Toma, C. L. (2014). Social sharing through interpersonal media: Patterns and effects on emotional well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 530e541.

[4]. Vitak, J., & Ellison, N. B. (2012). 'There's a network out there you might as well tap': Exploring the benefits of and barriers to exchanging informational and support-based resources on Facebook. New Media & Society, 15, 243e259

[5]. Jaidka, K. (2022). Cross-platform-and subgroup-differences in the well-being effects of Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook in the United States. Scientific reports, 12(1), 3271.

[6]. Li, J., & Zheng, H. (2020). Coverage of HPV-related information on Chinese social media: A content analysis of articles in Zhihu. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 16(10), 2548-2554.

[7]. Tang, Shiyi (2022). "How to Grow Your Business in Xiaohongshu - GPI Translations Blog". Globalization Partners International. Retrieved 2023-07-07.

[8]. Schlüter, C., Kraag, G., & Schmidt, J. (2021). Body shaming: an exploratory study on its definition and classification. International journal of bullying prevention, 1-12.

[9]. Zhang, P., Gao, Y., & Chen, S. (2019). Detect Chinese cyber bullying by analyzing user behaviors and language patterns. In 2019 3rd International Symposium on Autonomous Systems (ISAS) (pp. 370-375). IEEE.

[10]. Mishna, F., McLuckie, A., & Saini, M. (2009). Real-world dangers in an online reality: A qualitative study examining online relationships and cyber abuse. Social Work Research, 33(2), 107-118.

[11]. Smith, P. K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S., & Tippett, N. (2008). Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 49(4), 376-385.

[12]. Eatwell, R. (2006). Community cohesion and cumulative extremism in contemporary Britain. The Political Quarterly, 77(2), 204-216.

[13]. Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2007). Offline consequences of online victimization: School violence and delinquency. Journal of school violence, 6(3), 89-112.

[14]. Office of the Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission (2023). Guojia Hulianwang Xinxi Bangongshi guanyu Wangluo baoli xinxi zhili guiding (zhengqiu yijian gao) Gongkai zhengqiu yijian de tongzhi [Notice of the Cyberspace Administration of China on the Public solicitation of comments on the Provisions on Cyber Violence Information Governance (Draft for Comment)] Available at: http://www.cac.gov.cn/2023-07/07/c_1690295996362667.htm (Accessed: 25 July 2023).

[15]. Buckels, E. E., Trapnell, P. D., & Paulhus, D. L. (2014). Trolls just want to have fun. Personality and Individual Differences, 67, 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.016

[16]. Lumsden, K., & Morgan, H. (2017). Media framing of trolling and online abuse: Silencing strategies, symbolic violence, and victim blaming. Feminist Media Studies, 17(6), 926–940. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2017.1316755

[17]. Philips, F., & Morrissey, G. (2004). Cyberstalking and cyberpredators: A threat to safe sexuality on the Internet. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 10, 66-79.

[18]. Belknap, J., Chu, A. T., & DePrince, A. P. (2011). The roles of phones and computers in threatening and abusing women victims of male intimate partner abuse. Duke J. Gender L. & Pol'y, 19, 373.

[19]. Gong, L., & Hoffman, A. (2012). Sexting and slut-shaming: Why prosecution of teen self-sexters harms women. Georgetown Journal of Gender and the Law, 13(2), 577-590.

[20]. Poole, E. (2013). Hey girls, did you know: Slut-shaming on the internet needs to stop. USFL Rev., 48, 221.

[21]. Tanenbaum, L. (2015). I am not a slut: Slut-shaming in the age of the Internet. Harper Perennial.

[22]. Lee, C. (2022). Online abuse: Problematic for all Australians. Journal of Criminological Research, Policy and Practice. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JCRPP-02-2022-0006/full/html

[23]. Megan, L., & Judy, K. (2012). Online harassment among college students. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1369118X.2012.674959

[24]. Sengupta, A., & Chaudhuri, A. (2010). Are social networking sites a source of online harassment for teens? evidence from paper data. Children and Youth Services Review. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0190740910003208

[25]. Eckert, S. (2017). Fighting for recognition: Online abuse of women bloggers in Germany ... https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1461444816688457

[26]. Rodwell, E. (2019). Online trolling and its perpetrators: Under the cyberbridge. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1461444819859894

[27]. Suler, J. (2004). The Online Disinhibition Effect. Cyberpsychology & behavior : the impact of the Internet, multimedia and virtual reality on behavior and society. 7. 321-6. 10.1089/1094931041291295.

[28]. Noelle-Neumann, E. (1974). The Spiral of Silence a Theory of Public Opinion, Journal of Communication, Volume 24, Issue 2, Pages 43–51, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1974.tb00367.x

[29]. Hardaker, C. (2010). Trolling in asynchronous computer-mediated communication: From user discussions to academic definitions. UCLan. https://clok.uclan.ac.uk/4980/