1.Introduction

Earlier this year, the death of a Chinese girl, Linghua Zheng, captured the headlines of many media outlets. Zheng suffered from trolling attacks for six months merely because she posted a picture of visiting her seriously ill grandfather with hair dyed pink. Failing to defend herself by suing online trolls, Zheng committed suicide in March 2023 [1]. In the past two decades, similar tragedies have repeated worldwide [2]. A survey by Pew Research Center in 2021 shows that “four-in-ten Americans have experienced online harassment” [3]. A study conducted in China also demonstrates that trolls have been alarmingly active. Among 2,000 participants who are social media users, 40% of them have been trolled. 16% of the victims had suicidal thoughts, about 50% of the victims felt anxious and 32% were depressed, and 42% of the victims experienced insomnia [1]. All these incidents have significantly raised both the public and the scholars’ concerns, leading to an in-depth investigation of trolling.

Back in the 1980s, the development of computers and the relatively massive distribution of internet access made trolling an issue. Computer-mediated-communication, such as “email, chat relays, and forums,” provided “varying degrees of anonymity” and “impunity” for misbehaving online, thus creating a fertile ground for trolls [4-7]. Researchers then believed that trolls were “deviant, deceptive, aggressive, or antagonistic” [4-5]. Identifying trolls in that context needed precise insights into the norms of different websites to “distinguish between sincere/insincere or genuine/deceptive interactions” [7-8].

Yet, the rising of social media and the development of technologies within the past decades have dramatically changed the landscape of trolling and trolling-related studies. Nowadays, as a research topic, trolling has transformed from an online subculture to “the forefront of academic and media discourses about free speech, harassment, racism, and politics” [7]. Such a shift also raises a question for all concerned scholars: how to define online trolling? Researchers define trolling variously according to their field and experiences. For example, feminist and antiracist scholars propose that trolling is an identity-based attack [7, 9-11] while sociologists argue trolling is a form of antisocial behavior and intentions [6-7, 12-14]. Given this, this research tried to define trolling from the users’ point of view, determine their attitudes toward trolling/being trolled, and factors they considered contribute to trolling behavior. To quantitatively study these topics, this research utilized a survey as the research method to collect data and conduct cross-analysis to come up with conclusions.

2.Literature Review

Therefore, to address the issues discussed above, the literature review of this study paid attention to the definition of trolling, factors that contribute to trolling behaviors, and the effects of trolling researched by scholars and experts in this field. The goal of learning from selected articles was to gain a deeper insight into the current context of conducting trolling-related research and identify frameworks that might indicate directions for our following steps.

2.1.Definition of Trolling

Trolling, as an Internet slang word, is becoming a research focus in the field of social media studies. After reviewing many current papers, it was found that researchers have never reached a common agreement on how to define trolling. Trolling is often understood to have multiple meanings on different occasions. Trolling on the internet is mostly inflammatory, and its behaviors are seen as “a deliberate, deceptive and mischievous attempt that is engineered to elicit a reaction from the targets” [15].

Additionally, trolling seems to be an aggressive behavior, and it is always described as mentioned above. However, not only inflammatory behaviors constitute trolling. According to an online questionnaire, people are more likely to judge those trolling accounts as “essentially tend to trick people and make fun of them, or they have specific purposes,” like disturbing social platforms, baiting people into arguments, and misleading people’s views. Therefore, trolling differs from cyberbullying in scope and degree [16].

Regarding how researchers have defined trolling so far, most researchers have tended to define trolling by analyzing trolling incidents on specific sites [6]. In fact, those academic definitions are never compared to how people online understand trolling. Furthermore, some researchers dismissed users’ definitions, and the phenomenon also sparked interesting questions [7]. There is an ongoing debate that academic definitions of trolling are informed by analysis of trolling discourses but not how people who experienced trolling conceptualized it [7], which means previous researchers paid little attention to social media users, and the findings they got have a lower correlation between academic research and public.

Therefore, to narrow the definition gap between the scholars and the users, this research collected data from users themselves rather than merely context-analyzing social media posts. With the new perspective, this research explores how users define trolling.

2.2.Accelerator of Trolling Behaviors

It was found that personalities are vital factors that contribute to trolling behavior. Research revealed “the motives and personality characteristics of” online trolls through an online survey [17]. By recruiting more than 400 Reddit users and surveying their personalities and trolling behaviors, the researchers found that people with the “dark triad personality traits” —“narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy”— along with “schadenfreude” —were more likely to engage in trolling behaviors. That was because trolls with those personalities derive enjoyment from passively observing others suffer [17].

Other scholars identified the intention of harming others as the primary indicator of distinguishing online trolling [6]. Research conducted by Australian cyberpsychology experts March and Steele in 2020 found that trolls are always sadists who gain pleasure and stratification by hurting others’ feelings [18]. They recruited 400 participants through the Human Research Ethics Committee, Facebook and Reddit advertisements to take an online survey. By measuring participants’ trolling behaviors and the sadism trait, which indicates the proactivity of causing harm to others, with the Likert scale, researchers found that those receiving “higher scores that indicated more perpetration of trolling behaviors” also received higher scores of sadisms. Pearson correlations proved that the intention of hurting others was a significant positive predictor of trolling [18]. That is to say, other than personalities, sadism as a psychological trait can also accelerate trolling behaviors. Nevertheless, all of these studies explored the accelerator of trolling behavior from relatively more abstract dimensions. To this end, this research seeks to navigate further whether any demographic characteristics contribute to online trolling as well.

2.3.Effects of Trolling

In the previous research literature, the impacts of trolling were studied at the group and individual levels. There is no doubt that the negative effects made up the majority. From the group-level perspective, trolls can affect people’s communication and discussion in the internet community [19]. Because the internet is a “public area,” when trolling occurs, it may shift from one person’s comments to a group of people’s “wars,” so trolls can negatively impact the internet community. In addition, trolling can sometimes cause damage to network resources [15]. Because when trolling rises from an individual to a group level, it will inevitably occupy network resources, which may affect people’s use and search for network resources. Golf and Veer’s paper rethinks the definition and combat of online trolling, which also introduces the impact of trolling on the internet and its users.

Furthermore, trolling can also have a negative impact on websites. Nowadays, the internet is highly developed, so when trolling affects user experience, users may choose other internet websites or applications, affecting the website’s brand image and reducing the number of users [20]. McAloon studied why some celebrities leave Twitter in the article and explained the reason for the decrease in Twitter users.

From an individual level perspective, trolls can lead to some property losses [15]. When people encounter trolls, they feel psychological emotions like anger, inferiority, etc. Psychological changes can also affect people’s behavior, making them irritable and leading to unnecessary losses. Secondly, trolling can also cause psychological disorders (e.g., [21]), such as the impulse to self-harm, suicide, or depression, which can seriously affect people and people around them. Finally, online trolling can also affect the user’s sense of experience [15]. For example, when people open Weibo for entertainment and see negative comments, they inevitably feel unhappy and affect the user experience.

On the other hand, online trolling also has some positive effects. From the group-level perspective, trolls may promote people’s communication on social media and even increase the sales of certain items [22]. For example, when people argue, they will attract more people to join the debate, thus increasing the video’s or live streaming’s attention to increase sales and promote communication. Berger, Sorensen, and Rasmussen discussed how negative comments on the internet increase sales, such as some products that increase attention through negative advertising [22]. From an individual level perspective, trolling can affect those who do not participate in or oppose it [15]. To this end, this study thus also investigated the negative and positive effects of online trolling.

After analyzing themes and gaps that emerged in the current research, this study proposed the following three research questions: 1) How do Weibo users define online trolling? 2)What triggers Weibo users’ trolling behavior? 3)What are Weibo users’ psychological and behavioral reactions to being trolled?

3.Method

Weibo, the Chinese equivalent of Twitter, was launched in 2009. Currently, it is used by 248 million people daily. More importantly, its monthly active users amount to 573 million. In comparison, 322 million people use Twitter monthly [23]. All these factors make it one of the leading social media in China, which is why this research recruited participants from this platform. By targeting Weibo users, this research aims to cover as many social media users as possible.

To answer the research questions described above, this study designed an online survey with 20 questions to navigate Weibo Users’ subjective interpretations of online trolling quantitatively.

3.1.Participants

An online survey was conducted and distributed via a Wenjuanxing QR code from August 5, 2023, to August 9, 2023, to collect insight into Weibo users’ subjective perspectives on trolling. Due to the content and the nature of the survey, all collected samples were anonymous, confidential, and unidentified. Participants may stop finishing the questionnaire whenever they felt uncomfortable.

By posting the QR code on WeChat and sending it in group chats, 194 participants were recruited with the snowballing sampling. After deleting invalid samples with missing values or consistent choices, a total of 193 surveys were used for the following data analysis. The selected sample comprised 77 men, 112 women, and five individuals identified as other gender identities, including non-binary and undeclared. 138 out of 193 participants are 18-25 years old (71%.) 35 respondents’ ages ranged from 25 to 35 (18%). Eleven participants fell into the age group of 35-45 (6%), and 7 fell into the age group of 15-18 (4%). Besides that, one participant was under 15 years old (0.5%), and two participants’ ages ranged from 45 to 60 (1%).

3.2.Measure

To elicit target audiences’ experiences, feelings, and attitudes toward trolling or being trolled, the survey comprised 20 questions, including 11 demographic questions, two multiple-choice questions, and seven multi-answer questions. Collecting qualitative data through quantitative questions enabled this research to interpret how Weibo users construct their perception of trolling based on their subjective observations and experiences [24].

The demographic questions aimed to capture the characteristics of trolls or the victim of trolling, while the seven multi-answer questions were used to measure Weibo users’ perception of trolling from the dimensions of thoughts and behaviors. Additionally, every multi-answer question included an open-ended choice, enabling participants to raise any neglected point. Seven multi-answer questions included: 1) What behaviors do you consider constitute online trolling? 2)Which of the following issues or discussion topics are likely to attract online trolling behavior on Weibo in your experience? 3)What social media platforms do you see have the most trolling? 4)What have you or people you know been trolled for on Weibo? 5)Which of the following BEST describes any behavioral responses you or people you know have experienced after being trolled on Weibo? 6)Have you ever trolled on Weibo? 7) How do you interpret your actions when you troll on Weibo?

Multi-answer question 1, 2, and 4 were designed to measure how Weibo users defined trolling; therefore, provided choices included actions and topics that might constitute trolling. Additionally, Open-ended/leave-a-comment options were provided in case participants’ perspectives were not listed. Answers to Q3 were a list of popular social media platforms in China, which aimed to test how users sensed the overall trolling context on Weibo. Question 5 and 6 surveyed users’ responses to encountering trolling; thus, answers were lists of descriptions capturing individuals’ emotional or behavioral changes. Open-ended/leave-a-comment choices were also proved, just in case. Q7 was designed to identify Weibo users’ motivation for trolling; thus, potential reasons trigger trolling, and open-ended/leave-a-comment choices were listed.

3.3.Data Analysis

As explored in the literature review, the academe currently has not reached a consensus about defining online trolling as scholars summarize different definitions based on the nature of their research. One goal of this study is to explore whether users’ definitions of trolling and academic definitions have a gap. Other than that, the research also aimed to identify factors that impact individuals’ definitions of trolling and trigger trolling behavior, making this study a relatively more exploratory one with multi-dimensions. To this end, the research mainly employed cross-filtering to analyze collected data by examining the relationships of proposed dimensions.

4.Findings and Discussion

4.1.Defining Trolling and Gender Difference

Extent journal articles have analyzed the key element to define trolling, including “multidimensional,” aggressive, “antisocial,” or “deviant behaviors” [6-7, 12-14]. Therefore, referring to these studies, we designed our survey question of how users define trolling as a multi-answer/check all that apply the question, and answers included multiple actions that might constitute online trolling. When taking the survey, the respondents could select all choices they considered fit. The overall statistic of how participants define trolling is illustrated in the following pie chart.

Figure 1: What action(s) participants considered constituted trolling

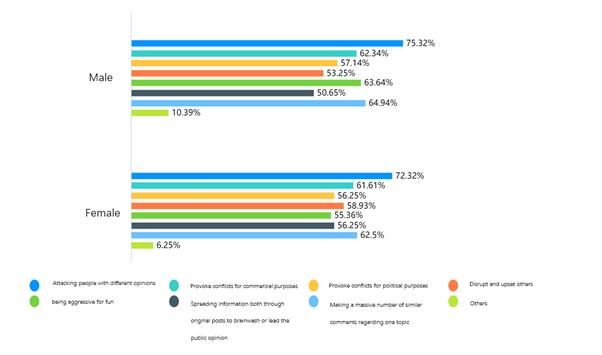

Among the 193 valid responses, there were 77 males (40%) and 111 females (58%). After cross-filtering the variables measuring what constitutes online trolling, this research failed to find any patterns between gender and individuals’ definition of trolling. As shown in chart 2, in all gender groups, most people believed that trolls mainly attacked people with different opinions online (57 men, 75% of the male group; 79 women, 72% of the female group). The majority of participants also chose other actions they considered trolling, including provoking conflicts for commercial purposes, leading public opinion by sending massive similar messages, and provoking conflicts for political purposes. Those three elements ranked the second, third, and fourth popular choices in both the male and female groups. Therefore, in view of this, it can be analyzed that there is no correlation between gender identity and individuals’ definition of online trolling. Meanwhile, among the 15 comments received from the open-ended/others choice, two-thirds believed that trolls suffered from intensive negative emotions offline, making social media their vent.

Yet, it is worth noting that 64% of male participants (49) considered “being aggressive for fun” as a form of trolling, yet 55% of female participants (62) held the same opinions. Even though there was a gap in the number, which might suggest men and women had different views in this dimension, the difference is relatively minor, which needs more samples to test this point further.

Figure 2: How different gender groups defined trolling behaviors

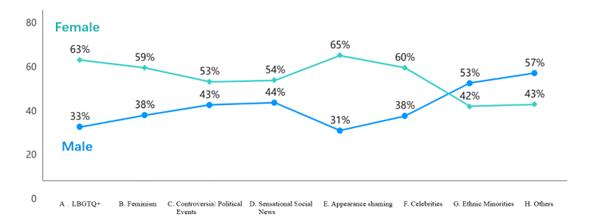

Moreover, a crossing-filtering between gender identity and agendas attracting most trolls was also done. Most people in all gender groups chose “feminism” as the topic involving the most trolls (60 men, 78% of the male group; 94 women, 84% of the female group.) Then, males and females ranked celebrities and entertainment-related topics as the second most attractive topic to trolls (53 men, 69% of the male group; 82 women, 75% of the female group). From this point of view, gender identity did not play a role in users’ perception of trolling either. Nevertheless, chart 3 also illustrated that males and females view the nature of appearance shaming considerably differently – more than half of females (67) considered the topic of appearance shaming involved more trolling. In contrast, only one-third of males (32) agreed.

Figure 3: How different gender groups define trolling topics

4.2.Defining Trolling and Residence Differences

As demonstrated in Chart 1, 143 out of 193 participants (74%) considered “attacking people holding different opinions” as the first element that made up the definition of trolling. One hundred twenty-five participants (64%) considered “sending massive similar comments to lead public opinion” as another crucial action that constitutes trolling. “Provoking conflicts for commercial or political purposes” respectively ranked as the third and fourth popular choice.

Nevertheless, a correlation was found after crossing flittering participants’ geographical residence and their definition of trolling behavior. Participants from North China chose “attacking others is trolling” as the leading element of trolling. “Sending massive similar comments to lead public opinion” was ranked as the second major trolling action. Yet, in Northeast China, “creating original posts to brainwash” was the second largest portion that made up the definition of trolling; Participants who lived in East China believed “disrupting and upsetting others” was the second major action of trolling. Southern residents also held a different opinion – they considered “being aggressive for fun” made up the second most vital factor of online trolling.

It needs to be highlighted that the samples from Southwest China defined trolling in a completely different way. 84% of participants in this region considered “provoking conflicts for commercial purposes” the first element of trolling, followed by “provoking conflicts for political purposes,” chosen by 68% of residents in this region. Moreover, the Northeast and Southwest areas are identified as “economically less-developed regions” in a public report released by the Chinese government in 2021 [25]. Still, as stated above, these two regions had a gap when defining trolling. This may suggest that the economic development of an area does not influence individuals’ definition of online trolling.

4.3.Trolling Behaviors and The Year of Becoming a Weibo User

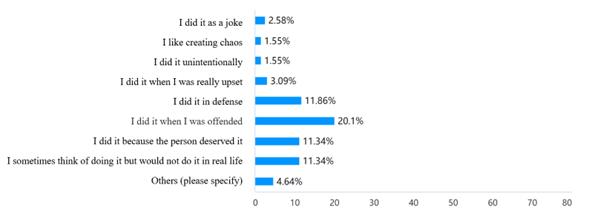

Even though 135 participants claimed that they would never troll online, accounting for 70% of the total number, 123 people also stated that they had trolled for reasons, mainly including “being offended,” “trolling back,” and “that one deserved” (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Reasons why participants trolled

It is worth noting that there is a negative correlation between the years of becoming a Weibo user and the proactivity of trolling. Collected data indicated that the longer an individual has been a Weibo User, the more defensive approach to trolling they tend to take. The cross-filtering illustrated that 34% of users (9 out of 26) on Weibo for more than ten years only trolled when they felt offended, while only 7.7% (2 out of 26) of them would troll those they considered bad actors. On the contrary, 15% (16 out of 105) of individuals using Weibo for 5-10 years would troll the one they considered unethical, double the more-than-10-year category. Meanwhile, only one-fifth (24 out of 105) in the five-to-ten-year group became trolls for offensive conversations.

4.4.Experience of Being Trolled and Average Daily Use Time of Weibo

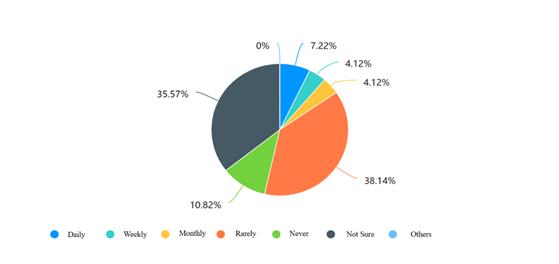

In general, when answering the question, “What is the frequency of you or people you know being trolled on Weibo,” most of the participants chose “rarely” (74 out of 193, 38%). Yet, as shown in the chart below, a considerable number of participants also checked that they had no clue of encountering trolls or not (69 out of 193, 36%). One assumption is that they chose the former answer to represent their own experiences, and the latter was chosen to describe their awareness of acquaintances’ experiences.

Figure 5: The frequency of participants and their acquaintances being trolled

Additionally, after cross-analyzing the collected data, no obvious pattern between the length of time that one spends on Weibo daily and the frequency of being attacked or harassed by trolls was found. Most participants had few experiences of being the victim -- 72 people chose “rarely,” accounting for 38% of the total; 69 had no sense of the frequency of being trolled, accounting for 36% of the total. That is to say, most samples had not encountered trolling behaviors profoundly. Even though 14 people stated that they are attacked by trolls every day, there was no convergence in their daily usage of Weibo. Therefore, an individual’s average time on Weibo does not influence their trolling-related experience.

4.5.Trolling and Effects

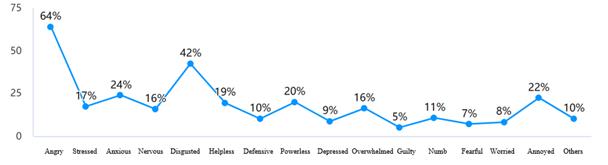

When surveying the psychological impacts of trolling, among 193 participants, 124 of them (64%) stated that they felt angry when being trolled. Disgusted (82 out of 193, 42%) and anxious (46 out of 193, 24%) were ranked second and the third most popular choices when participants described their feelings. Such results align with the above research (e.g., [21]). However, depression, one of the typical negative emotional responses to being trolled [26], appeared to be one of the least common reactions (17 out of 193, 9%) in this research.

Figure 6: Participants’ emotional reactions when being trolled

It also needs to be highlighted that, when exploring the behavioral response of being trolled, it was surprising to find that 80 out of 193 (41%) participants said that they would not have any behavioral changes even if they got trolled, which stood at the opposite side of reviewed studies. To further determine the gap here, the users’ behavioral responses and frequency of being trolled were cross filtered. The result indicated that most participants (31 out of 193, 39%) rarely encountered trolling. This might explain why they experienced no changes in their behavior – they had too few experiences facing trolling to be victims of suffering. Having limited negative emotional impacts, their psychological responses might not be intent enough to transform into actions.

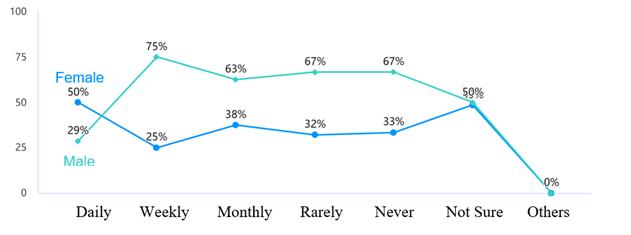

However, even though researchers have identified that females, especially female politicians, experienced more trolling attacks, this research found an opposite tendency [27-28]. In this research, for those who felt harassed by trolls, most male respondents considered they were under daily trolling attacks, while most female respondents considered the frequency of being trolled was weekly.

Figure 7: Different gender groups’ perceived frequency of being trolled

4.6.Discussion

To summarize, this study first calculated the basic statistics of multi-answer/check all that apply questions to analyze all collected data. Then demographic characteristics, including gender, age, educational background, relationship status, residence, habits of using Weibo, daily time spent on Weibo, years of becoming a Weibo user, and multi-answer/check all that apply questions were respectively cross-filtered to answer proposed research questions.

5.RQ1: How do Weibo users define online trolling?

It was found that most answers listed in the definition question received more than half of the approvals, representing that most participants have a very broad view of trolling. The result indicated that the behavior of attacking others online for holding different opinions, provoking conflicts for commercial or political purposes, disrupting and upsetting others, being aggressive for fun, spreading information through original posts to brainwash or lead the public opinion, making a massive amount of similar comments regarding one topic, and venting negative emotions individuals have in real-life constitute online trolling. Gender identifications did not play a role in impacting users’ general definition of trolling. However, more females considered appearance shaming a trolling topic compared to men, which might imply that women were more sensitive to men in this area. Yet, further studies need to be conducted to investigate the reasons behind this.

However, although Weibo Users’ definition of trolling is relatively broad, one theme identified in the previous research did not merge -- identity-based harassment [7]. Rather, trolling, defined by participants in this survey, was more in line with topic-based attacks. In respondents’ perceptions, trolling tends to happen more frequently in the context of a debate or an intensive conversation. As Ortiz (2020)stated in the article, one might be harassed for being colored or female without having any previous communication [7]. Nevertheless, on Weibo, identity-related factors, such as ethnic minorities, only trigger trolling when it initiates dialogues. Most users believed trolling would not begin until two-way communication happened.

6.RQ2: What triggers Weibo users’ trolling behavior?

Participants identified a considerably broad range of trolling, which might explain why more than 60% of respondents admitted that they had trolled (for various reasons). Even though most demographic characteristics were not detected in terms of impacting Weibo users’ trolling behavior, the cross-filtering between trolling behaviors and the year of becoming a Weibo user proved that the increase of years that individuals have been Weibo users can decrease the proactivity of their trolling behavior. Users on Weibo later tend to use trolling as a weapon to keep orders, protect the peace of their online community, and punish initial trolls who provoke conflicts. Nevertheless, as time goes by, senior Weibo users only troll when they are offended or aggressively challenged in online conversations.

7.RQ3: What are Weibo users’ psychological and behavioral reactions to being trolled?

Even though most participants stated that they experienced negative emotions when being trolled, such as anger, disgust, and annoyance, few of these feelings transformed into behavioral changes, which might imply that the intensity of their feelings did not hit the point that caused a qualitative change. Yet, the data collected in this survey was not sufficient enough to test this hypothesis. Other measurements, such as Likert scales, can be utilized to navigate this dimension more specifically. Moreover, being different from other studies, depression appeared to be a less significant emotional response to trolling, and factors that contributed to such a result were not observed.

Also, even though more females felt being trolled when talking about appearance, more males argued they are under a higher frequency of encountering online trolling. Such a deviation might imply that gender identities impacted individuals’ sense of being trolled, yet more research needs to be done to elaborate on how different gender groups perceive online trolling.

8.Conclusions

All in all, the result of this study proved that the majority of the sample population considers trolling as an online attack behavior, regardless of whether the reason is personal, commercial, or political. These can trigger emotional reactions, mainly anger and disgust, but have limited impacts in causing behavioral changes. Even though both men and women in this research similarly defined trolling, it was found that geographical residence was a factor that contributed to the variety of user-perceived trolling. Is the economic development of different regions the main reason causing such a phenomenon? Or do various cultural elements in different regions play a more influential role? Scholars might take this research as a starting point and specifically conduct regional studies on how diverse local social/cultural/economic/environmental contexts impacted social media users’ perception of online trolling. Focus groups and interviews can be powerful tools to explore this topic quantitatively.

Additionally, when surveying actions constituted online trolling, most of the participants who left comments mentioned that they believed that trolls provoke conflicts for commercial or political purposes were organized, which raised the agenda of professional trolls, those who are sponsored by corporates or governments to manipulate public opinion [29]. Factors contributing to such a perception might include ideologies, international relations, or recent political events. Scholars interested in this field can further explore how social media users identify the real purpose of trolls and why they believe these trolls are organized and sponsored.

It was also found that senior Weibo users’ trolling behaviors tend to be more defensive. Nevertheless, senior Weibo users often are considerably older than those who have become Weibo users for a shorter time. Does seniority alone trigger such a tendency? Or is it because younger users have more spare time to spend online? Concerned researchers could further explore differences in individuals’ social living conditions, such as incomes, to gain a more precise understanding.

Nevertheless, this research has its limitations. Firstly, when designing the online questionnaire, we tended to give more multi-answer questions but no open-ended questions. As a result, our participants were likely to be limited by the questions’ default options. Secondly, when sending out the survey, we first sent the questionnaire to our friends or family, and those people helped us reach out to their acquaintances, which essentially was the snowballing sampling. Although such an approach improved the efficiency of data collection, the population range was relatively narrow, mostly college students or adults aged 18-25 with similar social circles. This might lead to the homogeneity of the collected samples. Thirdly, the questionnaire was only open for a week, giving us a limited chance to gather a larger sample size. It would be better if we could get more time to collect more diverse samples nationwide to increase the authenticity of selected data further.

References

[1]. Huang, K. (2023, March 28). Zheng Linghua: The 23 Years Old Girl with Pink Hair is Gone, but Trolls are Still Here. BBC News (Chinese). https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/simp/chinese-news-65095783

[2]. Schwartz, M. (2008, August 3). The trolls among us. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/03/magazine/03trolls-t.html

[3]. Vogels, E. A. (2021, January 13). The State of Online Harassment. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/

[4]. Donath J. S. (1999). Identity and deception in the virtual community. In Smith M. A., Kollock P. (Eds.), Communities in cyberspace (pp. 29–59). Routledge.

[5]. Kim M.-S., Raja N. S. (1991, May 23–27). Verbal aggression and self-disclosure on computer bulletin boards [Paper presented]. 41st Annual Meeting of the International Communication Association, Chicago, IL, United States. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED.pdf334620

[6]. Hardaker C. (2010). Trolling in asynchronous computer-mediated communication: From user discussions to academic definitions. Journal of Politeness Research, 6(2), 215–242. https://doi.org/10.1515/JPLR.2010.011

[7]. Ortiz, S. M. (2020). Trolling as a Collective Form of Harassment: An Inductive Study of How Online Users Understand Trolling. Social Media + Society, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120928512

[8]. Herring S. C. (1999). The rhetorical dynamics of gender harassment online. The Information Society, 15(3), 151–167.

[9]. Gray K. L. (2012). Deviant bodies, stigmatized identities, and racist acts: Examining the experiences of African-American gamers in Xbox Live. New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia, 18(4), 261–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614568.2012.746740

[10]. Gray K. L., Buyukozturk B., Hill Z. G. (2017). Blurring the boundaries: Using Gamergate to examine “real” and symbolic violence against women in contemporary gaming culture. Sociology Compass, 11(3), Article e12458.

[11]. Vera-Gray F. (2017). Talk about a cunt with too much idle time: Trolling feminist research. Feminist Review, 115(1), 61–78. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41305-017-0038-y

[12]. Buckels E. E., Trapnell P. D., Paulhus D. L. (2014). Trolls just want to have fun. Personality and Individual Differences, 67, 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.016

[13]. Phillips W. (2015). This is why we can’t have nice things: Mapping the relationship between online trolling and mainstream culture. MIT Press.

[14]. Sanfilippo M. R., Fichman P., Yang S. (2018). Multidimensionality of online trolling behaviors. The Information Society, 34(1), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2017.1391911

[15]. Golf-Papez, M., & Veer, E. (2017). Don’t feed the trolling: rethinking how online trolling is being defined and combated. Journal of Marketing Management, 33(15-16), 1336-1354.

[16]. March, & Marrington, J. (2019). A Qualitative Analysis of Internet Trolling. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 22(3), 192–197. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0210

[17]. Brubaker, P. J., Montez, D., & Church, S. H. (2021). The Power of Schadenfreude: Predicting Behaviors and Perceptions of Trolling Among Reddit Users. Social Media + Society, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211021382

[18]. March, E., & Steele, G. (2020). High esteem and hurting others online: Trait sadism moderates the relationship between self-esteem and internet trolling. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(7), 441–446. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0652

[19]. Dahlberg, L. (2001). Computer-mediated communication and the public sphere: A critical analysis. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 7(1). doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2001.tb00137.x

[20]. McAloon, J. (2015, September 30). Why do celebrities like Lena Dunham leave Twitter? Telegraph. Retrieved from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/tvandradio/11537494/Why-do-celebritiesleave-Twitter.html

[21]. NetSafe. (2012, February 24). Submission on NZLC IP27: The news media meets “new media”: rights, responsibilities and regulation in the digital age. Retrieved from http://www.lawcom.govt.nz/sites/default/fifiles/submissionAttachments/39%20NetSafe.pdf

[22]. Berger, J., Sorensen, A. T., & Rasmussen, S. J. (2010). Positive effects of negative publicity: When negative reviews increase sales. Marketing Science, 29(5), 815–827. doi:10.1287/mksc.1090.0557

[23]. Galov, N. (n.d.). 19+ Weibo Statistics: Is it bigger than twitter in 2023?. WebTribunal. https://webtribunal.net/blog/weibo-statistics/#gref

[24]. Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A method sourcebook. SAGE.

[25]. Li, K. (2021). Government Work Report. https://www.gov.cn/zhuanti/2021lhzfgzbg/index.htm

[26]. Hong, F.-Y., & Cheng, K.-T. (2018). Correlation between university students’ online trolling behavior and online trolling victimization forms, current conditions, and personality traits. Telematics and Informatics, 35(2), 397–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.12.016

[27]. Fichman, P., & McClelland, M. W. (2020). The impact of gender and political affiliation on trolling. First Monday, 26(1). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v26i1.11061

[28]. Akhtar, S., & Morrison, C. M. (2019). The prevalence and impact of online trolling of UK members of Parliament. Computers in Human Behavior, 99, 322–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.05.015

[29]. Mihaylov, T., Koychev, I., Georgiev, G., & Nakov, P. (2021). Exposing paid opinion manipulation trolls. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.13726.

Cite this article

Xu,S.;Chen,Z.;Yuan,W. (2024). A Quantitative Exploration: Weibo Users’ Perception of Trolling. Communications in Humanities Research,28,282-294.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Global Politics and Socio-Humanities

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Huang, K. (2023, March 28). Zheng Linghua: The 23 Years Old Girl with Pink Hair is Gone, but Trolls are Still Here. BBC News (Chinese). https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/simp/chinese-news-65095783

[2]. Schwartz, M. (2008, August 3). The trolls among us. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/03/magazine/03trolls-t.html

[3]. Vogels, E. A. (2021, January 13). The State of Online Harassment. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/

[4]. Donath J. S. (1999). Identity and deception in the virtual community. In Smith M. A., Kollock P. (Eds.), Communities in cyberspace (pp. 29–59). Routledge.

[5]. Kim M.-S., Raja N. S. (1991, May 23–27). Verbal aggression and self-disclosure on computer bulletin boards [Paper presented]. 41st Annual Meeting of the International Communication Association, Chicago, IL, United States. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED.pdf334620

[6]. Hardaker C. (2010). Trolling in asynchronous computer-mediated communication: From user discussions to academic definitions. Journal of Politeness Research, 6(2), 215–242. https://doi.org/10.1515/JPLR.2010.011

[7]. Ortiz, S. M. (2020). Trolling as a Collective Form of Harassment: An Inductive Study of How Online Users Understand Trolling. Social Media + Society, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120928512

[8]. Herring S. C. (1999). The rhetorical dynamics of gender harassment online. The Information Society, 15(3), 151–167.

[9]. Gray K. L. (2012). Deviant bodies, stigmatized identities, and racist acts: Examining the experiences of African-American gamers in Xbox Live. New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia, 18(4), 261–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614568.2012.746740

[10]. Gray K. L., Buyukozturk B., Hill Z. G. (2017). Blurring the boundaries: Using Gamergate to examine “real” and symbolic violence against women in contemporary gaming culture. Sociology Compass, 11(3), Article e12458.

[11]. Vera-Gray F. (2017). Talk about a cunt with too much idle time: Trolling feminist research. Feminist Review, 115(1), 61–78. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41305-017-0038-y

[12]. Buckels E. E., Trapnell P. D., Paulhus D. L. (2014). Trolls just want to have fun. Personality and Individual Differences, 67, 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.016

[13]. Phillips W. (2015). This is why we can’t have nice things: Mapping the relationship between online trolling and mainstream culture. MIT Press.

[14]. Sanfilippo M. R., Fichman P., Yang S. (2018). Multidimensionality of online trolling behaviors. The Information Society, 34(1), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2017.1391911

[15]. Golf-Papez, M., & Veer, E. (2017). Don’t feed the trolling: rethinking how online trolling is being defined and combated. Journal of Marketing Management, 33(15-16), 1336-1354.

[16]. March, & Marrington, J. (2019). A Qualitative Analysis of Internet Trolling. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 22(3), 192–197. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0210

[17]. Brubaker, P. J., Montez, D., & Church, S. H. (2021). The Power of Schadenfreude: Predicting Behaviors and Perceptions of Trolling Among Reddit Users. Social Media + Society, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211021382

[18]. March, E., & Steele, G. (2020). High esteem and hurting others online: Trait sadism moderates the relationship between self-esteem and internet trolling. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(7), 441–446. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0652

[19]. Dahlberg, L. (2001). Computer-mediated communication and the public sphere: A critical analysis. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 7(1). doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2001.tb00137.x

[20]. McAloon, J. (2015, September 30). Why do celebrities like Lena Dunham leave Twitter? Telegraph. Retrieved from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/tvandradio/11537494/Why-do-celebritiesleave-Twitter.html

[21]. NetSafe. (2012, February 24). Submission on NZLC IP27: The news media meets “new media”: rights, responsibilities and regulation in the digital age. Retrieved from http://www.lawcom.govt.nz/sites/default/fifiles/submissionAttachments/39%20NetSafe.pdf

[22]. Berger, J., Sorensen, A. T., & Rasmussen, S. J. (2010). Positive effects of negative publicity: When negative reviews increase sales. Marketing Science, 29(5), 815–827. doi:10.1287/mksc.1090.0557

[23]. Galov, N. (n.d.). 19+ Weibo Statistics: Is it bigger than twitter in 2023?. WebTribunal. https://webtribunal.net/blog/weibo-statistics/#gref

[24]. Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A method sourcebook. SAGE.

[25]. Li, K. (2021). Government Work Report. https://www.gov.cn/zhuanti/2021lhzfgzbg/index.htm

[26]. Hong, F.-Y., & Cheng, K.-T. (2018). Correlation between university students’ online trolling behavior and online trolling victimization forms, current conditions, and personality traits. Telematics and Informatics, 35(2), 397–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.12.016

[27]. Fichman, P., & McClelland, M. W. (2020). The impact of gender and political affiliation on trolling. First Monday, 26(1). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v26i1.11061

[28]. Akhtar, S., & Morrison, C. M. (2019). The prevalence and impact of online trolling of UK members of Parliament. Computers in Human Behavior, 99, 322–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.05.015

[29]. Mihaylov, T., Koychev, I., Georgiev, G., & Nakov, P. (2021). Exposing paid opinion manipulation trolls. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.13726.