1. Introduction

In the Middle Ages, the Sogdian people frequently appeared in ancient documents of various languages and established colonies all over the world, in which their images are found everywhere in the archeological sites [1]. Like other peoples of ancient times, the Sogdians played a variety of roles in various corners of the world, as farmers, blacksmiths, and stablemen etc., but their most famous occupation was as professional long-distance traders. In the field of long-distance trade, without exaggeration, the Sogdian ethnic group can be regarded as gaining dominance position on the ancient silk road. Sometimes they worked for the governments. called‘ortaq’in Mongol and Turk, or referred to ‘粟戈导译 (commercial and translation ethnicity of the Sogdian) ‘ in China, or sometime they conducted long-distance commerce as a group of private traders used their commercial knowledge and commercial senses to make profit on commodities. So why the Sogdian? Why can they reached the status of domination on the silk road but not other ancient nomad nations, such as Gaochang, which clearly had more strengths financially and maritally and closer to China? Based on analysis of various primary sources, this essay will argue that Sogdian ethnic group’s domination on the ancient silk road was rooted in their ethnic characteristics, which include three main elements 1. special patrilineal system and family-oriented ethnicity. 2. Commercial leaning-tendency and unique production 3 portable Sogdian Zoroastrianism religion. Besides, this essay will also argue that some Chinese institutions, such as using the silks to pay for debt or official’s salaries, also helped them to dominate the Silk Road to some certain extent.

2. Types of primary sources used

The first type of the sources I used is the Sogdian sources, such as the ‘Sogdian ancient letters’, the language is Sogdian, and authors were mostly Sogdian commoners, same as the audience of the sources. These kinds of source restore the life, or nation characteristics of the Sogdian to the greatest extent because they are the direct sources from the ethnic group under study. The second type of source is Chinese sources, such as 北史 (beishi) by liyanshou or 汉书 (Hanshu) by Bangu, these sources were written by dynasty’s official historians and they were created for contemporary intellectuals and bureaucrats, although they might had the shortcomings like exaggeration or prejudice toward foreign counties, they are fantastic sources used to complement the information from Sogdian sources so that the argument of the essay will not be Sogdian-centric, as Sogdian sources might something exaggerate Sogdian merits. Finally, some no-textual materials, such as excavations or paintings are included as complements to textual sources to restore history as it was to corroborate my argument. For the sake of non-native Chinese speakers, translations of all ancient Chinese texts cited will be provided in the brackets after the cited texts.

3. Family-oriented nation and special patrilineal system

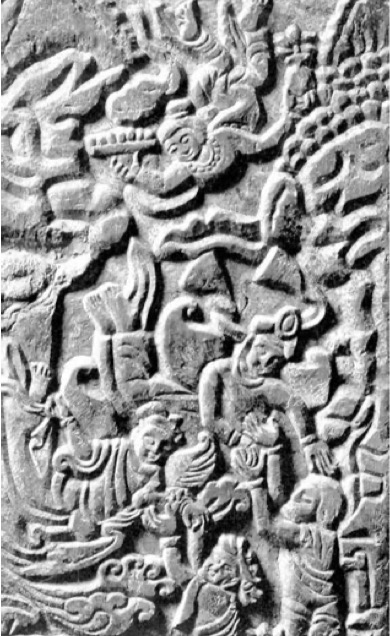

Strong family ties, or Strong family cohesion were the characteristics of many ancient nations, and the Sogdian nation was no exception. But in addition to Strong family ties/cohesion, another Sogdian national feature was light patriarchy/special patrilineal system, that is to say, a version of less intense patriarchy, and it was the combination of Family-oriented nation and special patrilineal system that made the Sogdian successful on the silk road. The Sogdian family ties/ cohesion was most reflected in their epitaphs. Taking recent excavations of Sogdian epitaphs in Guyuan as an example, these epitaphs were different from the traditional Han Chinese epitaphs, in which the contents were biographical and usually only the closest ancestors/offsprings would be mentioned (sometime no ancestors/offspring were mentioned at all, typical writing style of Chinese historians, as can be seen from 史记Shiji), the most prominent of feature of these Guyuan Sogdian epitaphs was the repeated and deep reference to the ancestors. For example, the Shi Pantuo epitaphs found in Guyuan Shi family excavations recorded three ancestors (father, grandfather and great-grandfather) along with Shi Pantuo’s seven sons, and similar phenomenon also can be found in Shi Putuo’s sons’ epitaphs, which prove the intensities of Sogdian’s family attachment and cohesion [2]. Regarding the Sogdian patriarchy the Sogdian letters discovered by Aurel Stein in 1907 are the direct Sogdian primary sources to be referred to. Looking at the Sogdian letter 1 we can clearly identify the patriarchy feature of Sogdian ethnic group, as the Sogdian women in the description cannot go back to her hometown if her husband, or her husband’s relative did not consent it in advance [3]. Similar patriarchal descriptions can be found in Sogdian letter 3 as well, in which extremely respectful honorifics from wives and daughters to their husband/father are found (e.g. ‘when I hear news of your good health, I consider myself immortal), and the male dominance family status also was exemplified in his wife’s absolute obedience, as the wife ‘took every command from her husband upon her head [3]. However, it is worth noting that although the patriarchal system of this ethnic group was obvious, it should be clarified that Sogdian version of patriarchy was light patriarchy, a special patrilineal system, which was different from the strong patriarchal tendency of Han and Germanic nations, and this can be reflected in the Sogdians' burial methods and sarcophagus frescoes. Taking the Guyuan Shi family’s cemetery as an example, one of the most stunning findings is that women were able be inscribed on epitaph along with her dignitary husband (e.g. Lady Kang, wife of Shi DaoLuo) or even had her own epitaph and equal size of coffin as her husband buried (e.g. Lady An Niang epitaph and coffin), which was unthinkable in contemporary Han Chinese culture [2]. A more stunning example of Sogdian special patrilineal system can be found on the Sabao Shi Jun‘s sarcophagus frescoes, which were excavated in Xi An and depicted the whole life cycle of the sarcophagus owner. Sogdian Sarcophagus frescoes depicting the deeds of their Sabao owner was a common phenomenon, but admittedly they usually only reflected the deceased’s life experience as leaders of immigrant communities (Sabao), therefore the whole life circle story (from born to death) carved on Shi jun’s sarcophagus frescoes is an exceptional case and requires a new way to examine it. Analyzing from the angle of Sogdian Buddhist belief, Jun Xi believes that the depiction of Shi Jun’s life circle is the reprint of the story of Prince Siddhartha, who became the Buddha eventually. However it is worth noting that the images of Shi jun‘wife appear in every single Line drawing of the narrative imagery on the Shi Jun sarcophagus; she thus accompanies She Jun from life to death, from man to god (Figure 1 and 2) [4].

Figure 1:Frescoes on West wall of Shijun’s sarcophagus

Figure 2:Frescoes on North wall of Shijun’s Sarcophagus

(Figure 1 (left) Figure 2 (right). Picture 1 shows Shi Jun’s wife holding a lotus, which resembled the lotus girl in the jataka story, when youthful Shi Jun was prostrating in front of the Buddha. The lotus girl was the key in helping prince Siddhartha became Buddha, so the artist here might want to emphasize the status of Shi Jun’s wife. Figure 2 shows a heavenly creature flying toward Shi Jun and his wife, when the couple reached their salvation)

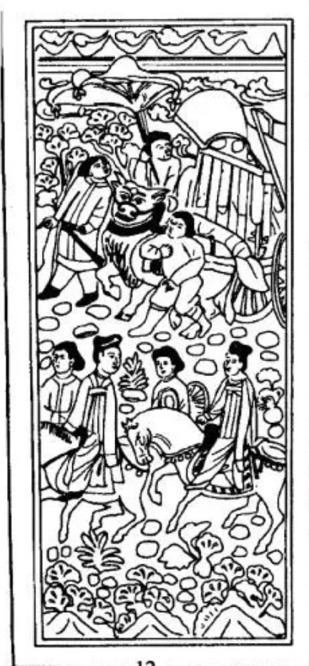

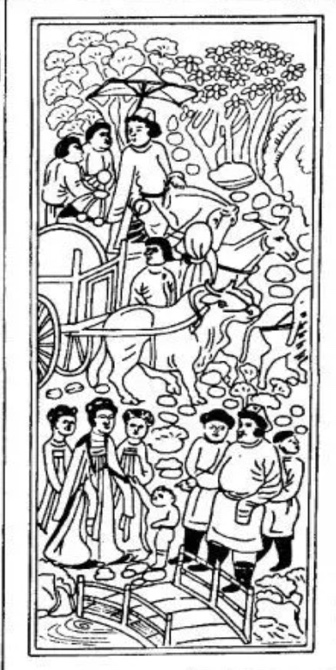

This phenomenon shows that the Sogdians' patriarchal system is not so strong compared with other civilizations, as women can be granted position of deference when alive (accompanying Shi Jun on every important occasion in the images)and could occupy half of the sarcophagi’s images when died ( even portrayed in the form of flower-selling girl, who was the protagonist in the story of Jataka, in Picture 1) [4]. Such a special patrilineal system proves that women enjoy a certain status in Sogdian society, which, combined with family cohesion, gave birth to the family Trust system. In the Sogdian family system, patriarchy encouraged male family members to provide for this family as long-distance traders (Sogdian ethnic group had strong commercial inclination, which will be mentioned below) .The female Sogdians stayed at central Asian homeland and took care of domestic affairs/properties sent back by their traders husband from the east because of their recognized domestic status, which is in sharp contrast to contemporary European women, for whom management of property would be extremely difficult because of patriarchal customary law such as Salic law. Therefore a working system conducive to development of long-term distance commerce was formed and this family trust system is illustrated in recent excavations as well, the most obvious one is the Carvings on the sarcophagus from the tomb of An Jia (Figure 3 and 4) .[1]

Figure 3: Frescoes on West wall of Anjia’s sarcophagus

Figure 4: Frescoes on Central wall of Anjia’s sarcophagu

(Figure 3 (left) and Figure 4 (right). The upper part of figure 3 shows a man riding an oxcart, and commodities inside the cart converted by the cart curtain can be seen faintly. The bottom part of the picture shows several women riding horses heading to the way the oxcart is going. According to Rong Xinjiang, a reasonable inference would be that those women were seeing their husband off but themselves stay at home to deal with properties sent back and domestic affairs [5]. Figure 4 shows a similar phenomenon, in which husband was heading to the east for trade in the upper part of the carving, and his wives stand in front of a bridge to see him off in the bottom part.)

In summary, same as other ancient civilizations, Sogdian ethnic group had strong family ties/cohesion, and judging from the perspective of how their epitaphs were written, in which more than three generations of ancestors and offsprings were mentioned, their family cohesion and ties might be stronger than others. In addition, light patriarchy, a special patrilineal system, is exemplified in excavations from Guyang Shi’s family cemetery and Shi Jun’s Sarcophagus frescoes. The combination of extremely strong family ties and special patrilineal system led to the formation of Sogdian family trust system, in which male family members were encouraged to reach out to provide for his family, and women were granted the right to deal with domestic affairs and properties/trade profit sent back from the east earned by their husbands, so undoubtedly this was an effective system support the Sogdian dominance on the silk road.

4. Commercial leaning-tendency/inclination and unique production

Turning now to some Chinese sources which prove two other distinguishing features of the Sogdian ethnicity, that were, commercial inclination and unique products. One of the most prestigious Chinese histographies <Wei Shu> recorded the Sogdian ethnic group like this ‘粟特国,在葱岭之西,古之奄蔡,一名温那沙...其国人先多诣凉土贩货’[6] (Translations: Sogdian oasis states were located west of Chongling, whose ancient name was Yancai or Wennasha….The people living there were called Sogdian as well, and the majority of people worked as long-distance traders who traveled to the east to conduct commercial business), which indicates a blatantly strong commercial orientation of the Sogdian ethnic group. A similar description can also be found in the famous Xuanzang record of the western region,’ 自素叶水城至羯霜那国。地名窣利。人亦谓焉…志性恇怯。风俗浇讹。多行诡诈。大抵贪求。父子计利。财多为贵。良贱无差。虽富巨万服食粗弊。力田逐利者杂半矣’ [7].(Translation: The territory from Yeshui city to Kesh was Sogdians’ territory. The Sogdians living on these lands were equable and shrewd, in most cases also very avaricious. The most popular and traditional occupation for a Sogdian was a merchant, indeed a merchant father died his sons took over his businesses, and they always try to gain as much wealth as possible. The Sogdians’social stratas were ambiguous, they did not care about genealogy, even the wealthiest could eat the food eaten by the commoner. In addition to long-distance traders, there were still a small number of peasants on these lands.). Moving on, 栗弋国属康居。出名马牛羊,蒲萄众果,其土水美,故蒲萄酒特有名焉 [8] (Translation: The Sogdian states were ruled by Sogdian ethnic group. These states were known for their export of cows, sheep and grapes. Their soils were very fertile, therefore their wine, which was made of grape, was very reputable in China) , attested to another features of the Sogdian nation, that is their occupation of rich lands that produced unique regional products., such as 牛羊 (cow/sheep),葡萄 (grape),which were the products the sedentary dynasties did not produce but demanded in large quantities, and this was also reflected in the names of the colonies they built within the Chinese border, ‘蒲桃城,南去石城镇四里。康艳典所筑,种蒲桃于此城中,因号浦桃城(Translation: The Sogdian city of Putao [Putao is the pronunciation of grape in Chinese] is 4 kilometers south of the Sogdian town of Shicheng. The city was built by a Sogdian named Kangyandian and is called Putao because the Sogdian living there grew and exported grapes. From local chronicles of the regions of Dunhuang and Yi, Tang dynasty, author unknown) [5]. So clearly, they brought the technology of cultivating grapes to their east Asian colonies. In addition, some recent excavations, such as the sarcophagus paintings (figure3) suggest that the Sogdians gathered in China to produce wine out of the rape they grew, a luxury item most in demand by the Chinese elites.

Figure 3: Stone coffin murals in Tianshui City.

(In the picture, three people on the top stage are looking down at two carved animal heads, from which freshly brewed wine flows into two containers. A servant stands in the middle of those carved stone animal head and decants the wine into bottles. Besides him are two other servants, one of them smells the wine with two bottles in his hand, one of them kneed on the ground and is drinking the wine)

The combination of features of commerce inclination and production of unique products demanded by distant lands promoted the Sogdian ethnicity’s obsession with long-distance business , and this brought two consequences. The first one was the depoliticalized nature of the Sogdian states. The depoliticalized or deterritorlized nature of the Sogdian meant various small Sogdian governments with decentralized internal political structure were formed (this is also the reason why there were so few records about the Sogdian exist in ancient Chinese histographies, which were known for their focuses on political and diplomatic matters), as these would lead to less regulations and greater flexibilities for far-flung commerce[9]. The result was that small Sogdian states were often fragmented, sometimes in loose coalitions, so that their territories were not the focus of great powers' struggles because of their size and political/military importance and usually did not have formal diplomatic relations with other great powers. The depoliticalized nature of the Sogdian nation was particularly obvious compared with other similar nomads, such as nomad Gao Chang (高昌), which was almost identical with the Sogdian geographically and commercially. The unified and centralized Gao chang government made it inevitable for Gao chang to choose a side between Turks or the Chinese to stand with, so it could never be as flexible as the small Sogdian countries, which had good relations with both the Chinese and the Turks. No matter which side Gao chang chose the other side would block its commercial developments or even try to destroy the Gaochang, as exemplified by the war waged by emperor Taizhong of Tang. Along with the depoliticization and deterritorlization was the development of Sogdian commercial institutions and commercial sense, which were another consequence of their obsession with long-distance commerce. The Sogdian’s commercial institutions, which were more advanced than that of their contemporaries, was mainly reflected and obvious in the recent excavations such as ‘Sogdian contract for the purchase of a slave from the era of the Kara-Khoja State of the Qu Clan [10]‘In this document, it can be found that very mature commercial institutions were developed by the Sogdian, such as the signing of the contract must have witnesses, and in the case of this contract, there were four witnesses of the contract. In addition, Sogdian merchants also seek the local government to issue transaction permits and certificates, which provides another layer of guarantee for the transaction. The Sogdians' fascination with long-distance commerce also led them to develop a replenishment system similar to the Chinese depot system (驿站 yizhan), which was established around 13 centuries in the Yuan dynasty, centuries later than the Sogdian. These settlements that built by the Sogdian along the Silk Road, such as the one at Lop Nor Area and Mongolia Basin, were acting as supply depots for the Sogdian merchants conducting long-distance business, something even functioned as cargo exchange market for the Sogdian brokers[11]. An exemplar of such settlements was the Sogdian settlement in Kara-Khoja region, which not only supplied the Sogdian merchants passing by, but also acting as the exchange market for the Sogdian brokers, so that the brokers lived or stayed there could obtain needed goods and exported the goods both east and west without traveling long distance[12]. Similar record can also been found in the Sogdian letters, in which the asset management skill of the Sogdian nation was presented. In the Sogdian letter 2 we can see a Sogdian slave named Nanai-vandak committed his properties to his lord because he was in the middle of war in China and begged his lord (Varzakk and Nanai-thvar) to use the assets he left at Sogdian homeland to invest so that his son Takhsich-vandak can rely on the profit generated from his asset when he grew up [3]. In a word, after analyzing the primary sources we can draw the conclusion that the Sogdian ethnic group had strong commerce-leaning tendency and unique production activities. These national characteristics promoted their obsession with long-distance business, which led to two results, one of them was the depoliticization of the Sogdian nation, the other was their commercial institutions and commercial sense that were more advanced than any other country at that time and undoubtedly this chain of reaction (commercial leaning tendency + unique production= depoliticization+ advanced commercial institutions and commercial sense= domination in the silks roads) helped the Sogdian nation dominated the ancient silk road.

5. Religious aspect

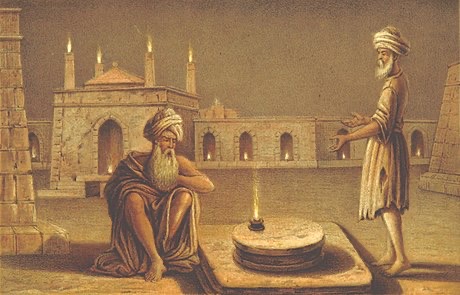

Many ancient civilizations were theocracies, in which the laws and politics were closely correlated with religion, however the majority of them needed to establish churches/mosques/temples to conduct ritual activities to make the system of combination of daily life and religion work, but the Sogdians could carry their god everywhere during the period under discussion as the result of Islamic conquest, where no specific geographical locations were required, so this may be another reason why the Sogdian could dominated the land silk road in the medieval age [1]. Sogdians believed in Zoroastrianism, a religion that values rituals and places of worship. For the Zoroastrians, a temple with continuously burning fire was usually required and the fire from the fire temples must have special sanctity, since ‘the temple [fire] is that of the hearth fire raised to a new solemnity ‘and the ‘the Atash-i Vahram [literally: "victorious fire",and the lesser Atash-i Adaran, ( 'Fire of Fires',) a parish fire, as it were, serving only a village or town quarter" [13]. But it was a religion that valued ceremony and places of worship enormously underwent a major qualitative change between the 6th and 10th centuries, allowing it to become a thrust for the Sogdian nation to dominate the ancient land silk road. Zoroastrianism’s domination in central Asia was collapsing as the Sassanid empire was overthrown by the Arabs over the course of a decade in the 7th century, the persecution of Zoroastrians by Muslims was intensifying in the following years, and this was the reason why Zoroastrianism began to simplify its requirement for ceremony and places of worship because they need to immigrant to regions that had a more tolerant climate [14]. This simplification had two consequences. One was that the sanctity of the fire worshiped by Zoroastrianism was no longer associated with the temple flame. For example, in this 19th century painting, we can see the phenomenon of Zoroastrians praying to the fire outside, so it is reasonable to speculate that this kind of behavior had been going on for some time, mostly likely started from the 7th century Islamic conquest, and was regarded as normal worship behavior in the 19 century.

Figure 4 (The fire temple of Baku, 1860, author unknow)

In addition, from some Chinese textual sources we can find further evidence that the Sogdians developed the portability of Zoroastrianism during the Tang dynasty, and this was another consequence of the simplification of Zoroastrianism. The Zoroastrianism idol, the same as the holy fire, could be carried on camel’s back then.

‘突厥事祆神,无祠庙,刻氈为形,盛于皮袋,行动之处,以脂苏涂之。或系之竿上,四时祀之’ 唐段成式《酉阳杂俎》卷四[15]’(translation: The Sogdians were Zoroastrianism believers, a religion that had no temples. Their god idols were made of wool or wood and placed on leather or carried in bags. These idols travelled with them everywhere and whenever they needed to worship the idols they put the idols out and painted them, or tied the idols with a stick then they prostrated in front of the idols. 《The Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang》 by Duan ChengShi, Tang dynasty.). This textual evidence about the portability of Zoroastrianism is further corroborated by the excavations found in the tomb of General Anti of the Tang dynasty.

Figure 5 The camel figurine from the tomb of General Anti

(The Tang Sancai ceramics from the tomb of General Anti, a typical example of how Zoroastrianism idols were carried in the Tang dynasty. The saddle on the camel’s back was carved into the Zoroastrianism idols’ shape and star decorations were found on both sides.of the idol.[16]). In a word, Zoroastrianism went through quanlitative change because of the Islamic conquest began around the 6-7 centuries, which simplified the Zoroastrianism requirements of places of worship, and as a result led to the development of the portability of the Zoroastrianism. The development of portability was exemplified in two modalities, the first one was that the sanctity of fire now was longer associated with temple, as we can see the in the behaviors of worshiping fire outside the fire temples in later artist’s painting. The second modality was similar, the Zoroastrianism idols back then could be carried everywhere, as embodied by the Chinese textual source and the Tang Sancai ceramics excavated from the tomb of General Anti of the Tang dynasty. The development of the portability of Zoroastrianism allowed the religion to become a driver for Sogdian domination on the silk roads as its medieval counterparts usually set particular places to worship at specific time.

6. Chinese silks as international currency:

Coins were common currency used in the Middle Ages, but when investigating any ancient period, one should always keep in mind that various metals used as legal tender were scarce resources because of inefficient ancient mining technology. For the ancient traders a substitute currency that was easy to carry or identify was thus necessary, and due to the Chinese custom of using silks to pay mandarins and soldiers, silks eventually became an important substitute for coins [17]. From some Chinese textual sources, such as the book of later Han, the phenomenon of using silks as payment can be clearly identified ‘三年春正月甲子,皇帝加元服.... 赐民爵及粟帛各有差,货币杂用布、帛、金、粟 [8].(Translation: In the third year of emperor Heng, the emperor took over the government upon coming of age. To celebrate, the emperor thus gave his court’s members a raise, and gold, silks and corps were used as methods of payments) The description of using silks as salary payment for soldiers is also easy to find, and the following one emphasizes how common the method was and also how desirous the soldiers were for being paid with silks ‘是月二十八日,横水军至太原,请出军优给。旧例第一军绢二疋,时刘沔交代后,军库无绢。石以己绢益之。方可人给一疋,便催上路’[18] (Translation: On December 28th , the Hengsui army went to Taiyuan and they asked for salary. According to the law they will be paid in silks, but officer LIuxi found that there were not enough silks in the military warehouse. Therefore, Liuxi decided to dispense his own silks to the soldiers so that those soldiers were willing to go to the battlefield). The practice of using silks as a way of salaries payments led to the result that silks as a currency were gradually accepted in extensive regions, because Chinese dynasties as a whole/prominent officials gave silks as gifts to nomadic kingdoms often, and Chinese frontier troops who received silks as payment needed to trade with nomadic locals with silks in exchange for necessities. Stein found a kind of silk called 綵 in the beacon tower #XV in Dunhuang, which was the kind of silk specially created for making payments, therefore 綵 usually had different colors or lengths representing different values. Furthermore, the Chinese inscriptions written on the 綵 mentioned above suggests a direct relation between 綵 and trade, from which we can tell the value of this 綵 was 600 Chinese copper coins,[19] Similar 綵 was also found in the Niya region (today’s south XingJiang), which was located between ancient kingdoms of Khotan and Loulan. The discoveries of 綵 in Niya is particularly meaningful because it was the middle point between the two powerful ancient central Asian countries. Many ancient reports from long-distance traders about stolen goods have been found in this region, which suggests that silks were at least used in the kingdoms of Khotan and Loulan as a kind of currency. The officials of the Nina region called those long-distance traders whose goods were stolen or robbed ‘refugees ‘(or ‘palayamna’ in the original Balinese script), and their reports provide further evidence about the importance of silks as an international currency, as silks were mentioned extensively in the ancient reports made by the palayamana [19]. In summary, silks were an ideal substitutes for coins for the long-distance traders, as it has the features of recognizability and portability, sometime even durability if preserved in the right way. Chinese custom of using silks as a way of salaries payment spread this silks currency to extensive central Asian regions, such as Duhuang, Niya and Khotan/Loulan, which is exemplified by the discoveries of 綵 in aforementioned regions. Although the causation is indirect, the existence of such international currency must have been utilized by the Sogdians to pay in a multitude of different monetary regions, which undoubtedly assisted the Sogdians in dominating the silk road by land.

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, from various textual/material materials, Sogdian ethnic characteristics can be further recognized, which can be summarized as (special) patriarchy, commercial inclination and unique production, and portable Zoroastrianism. These ethnic characteristics helped them to dominate the land silks road. Firstly, the combination of strong family bond and light patriarchy allowed for a male-dominated authoritarian system, but in which women had certain degree of recognized status. This special patrilineal system allowed the male family members to reach out for commercial activities and leave women at home for domestic affair/property management,[1] ensured the possibilities and sustainability of long-distance commerce. Secondly, the national feature of commerce inclination and the production of unique exotic products created the need of exportations and thus caused the depoliticalized nature of the Sogdian ethnic group and catalyzed the development of Sogdiana’s advanced commercial institutions. The depoliticalized nature of the Sogdian ethnic group made the nation keeping good relations with various ancient polities, especially the ancient superpowers Chinese and Turks; the advanced commercial institutions they developed because of their obsession with long-distance trade provided them the advantage other contemporary nomads did not enjoy. Finally, after the 6-7th Islamic conquest the portability of Zoroastrianism, which was exemplified in the examples of portable fires and idols, was developed by the Sogdian, and no requirements of times and locations of worship certainly helped the Sogdian to dominate the silks road. Besides the ethnical features, this essay argues that some Chinese institutions, such as the Chinese habits of using silks as way of salary payment, made the Chinese silks gradually accepted as an international currency, which helped the Sogdian to dominate the silks road because they could use silks to pay in different monetary regions back then.

References

[1]. Xinjiang Rong, Medieval China and Sogdian culture (Chinese edition), (Hong Kong: 2014)

[2]. Patrick Wertmann and Mayke Wagner etc. Sogdian careers and families in sixth- to seventh-century northern China: a case study of the Shi family based on archaeological finds and epitaph inscriptions, The history of the family, 22 (1), 2016, 103-135

[3]. Sims-Williams Nicholas, The translations of the Sogdian ancient letters 1,2,3,5, school of oriental and African studies, university of London

[4]. Jin Xu, a journey across many realms: the Shi jun sarcophagus and the visual representation of migration on the silk road, the journal of Asian studies, 80(1), 2021,145-165

[5]. XinJiang Rong, Medieval China and Foreign Civilizations (Chinese edition), revised edition,, (Hong Kong: 2021)

[6]. Sturgeon Donald, “Wei Shu,” Chinese Text Project, accessed September 22, 2022, https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&chapter=184704&searchu=%E7%B2%9F%E7%89%B9&remap=gb,

[7]. Sturgeon Donald, “Xuan Zang’s records of the western regions.” Chinese Text Project. Accessed September 22, 2022.https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&res=944265&searchu=%E8%87%AA%E7%B4%A0%E5%8F%B6%E6%B0%B4%E5%9F%8E%E8%87%B3%E7%BE%AF%E9%9C%9C%E9%82%A3%E5%9B%BD%E3%80%82%E5%9C%B0%E5%90%8D%E7%AA%A3%E5%88%A9%E3%80%82&remap=gb.

[8]. Sturgeon Donald, “Book of Later Han.” Chinese Text Project. Accessed September 22, 2022. https://ctext.org/hou-han-shu/xi-yu-zhuan/zhs?searchu=%E6%A0%97%E5%BC%8B%E5%9B%BD%E5%B1%9E%E5%BA%B7%E5%B1%85%E3%80%82%E5%87%BA%E5%90%8D%E9%A9%AC%E7%89%9B%E7%BE%8A%EF%BC%8C%E8%92%B2%E8%90%84%E4%BC%97%E6%9E%9C%EF%BC%8C%E5%85%B6%E5%9C%9F%E6%B0%B4%E7%BE%8E%EF%BC%8C%E6%95%85%E8%92%B2%E8%90%84%E9%85%92%E7%89%B9%E6%9C%89%E5%90%8D%E7%84%89&searchmode=showall#result.

[9]. Vaissiere de La ,Etienne. (2018). Sogdian traders: a history. trans Jame Ward (Boston, 2005).

[10]. Yoshida Y, Moriyasu T, and Xinjiang Museum, “Sogdian Contract for the Purchase of a Slave Girl from the Era of the Kara-Khoja State of the Qu Clan,” Nairiku ajia gengo no kenkyu (Study of inland Asian languages) 4 (1988) 1–50

[11]. Yoshida Yutaka, The Sogdian Merchant Network, Teikyo university, Research institute of cultural properties, (article published online:2021),https://oxfordre.com/asianhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277727-e-491, accessed 22, 9, 2022

[12]. N Cosmo, DI., & M. Maas. (Eds.). Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity: Rome, China, Iran, and the Steppe, ca. 250–750. (Cambridge:2018)

[13]. Mary Boyce, "On the Zoroastrian Temple Cult of Fire", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 95 (3) (1975), 454-465

[14]. Mary Boyce, Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, (London:2000)

[15]. Sturgeon Donald, “The Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang ” Chinese Text Project, accessed September 22, 2022,https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=en&res=895322&searchu=%E8%84%82%E8%8B%8F%E6%B6%82&remap=gb.

[16]. Bo qing Jiang, Tang sancai Ceramicses from tome of General Anti ‘ the gods that were carried everywhere’ ——— a discussion on Sogdian Zoroastrianism belief , Chinese edition, Tangyanjiu (Chinese journal of Tang research) Vol: 7

[17]. Helan Wang, Money on the Silk Road, (London:2004)

[18]. Sturgeon Donald. “Jiu Tangshu.” Chinese Text Project. Accessed September 22, 2022. https://ctext.org/library.pl?if=gb&file=61171&page=45&remap=gb#%E6%97%A7%E4%BE%8B%E7%AC%AC%E4%B8%80%E5%86%9B%E7%BB%A2%E4%BA%8C.

[19]. Hanse Valerie, The place of coins and their alternatives in the Silks road trade, Chinese edition,in proceedings of the Symposium on ancient coins and the culture of the silks road. (Shang Hai :2011)

Cite this article

Liu,L. (2023). An Analysis of the Success of Sogdian Commerce on the Silk Roads base on the Sogdian’s National Characteristics and Chinese Institutions from Perspective of Primary Sources (581-901). Communications in Humanities Research,4,336-347.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies (ICIHCS 2022), Part 2

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Xinjiang Rong, Medieval China and Sogdian culture (Chinese edition), (Hong Kong: 2014)

[2]. Patrick Wertmann and Mayke Wagner etc. Sogdian careers and families in sixth- to seventh-century northern China: a case study of the Shi family based on archaeological finds and epitaph inscriptions, The history of the family, 22 (1), 2016, 103-135

[3]. Sims-Williams Nicholas, The translations of the Sogdian ancient letters 1,2,3,5, school of oriental and African studies, university of London

[4]. Jin Xu, a journey across many realms: the Shi jun sarcophagus and the visual representation of migration on the silk road, the journal of Asian studies, 80(1), 2021,145-165

[5]. XinJiang Rong, Medieval China and Foreign Civilizations (Chinese edition), revised edition,, (Hong Kong: 2021)

[6]. Sturgeon Donald, “Wei Shu,” Chinese Text Project, accessed September 22, 2022, https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&chapter=184704&searchu=%E7%B2%9F%E7%89%B9&remap=gb,

[7]. Sturgeon Donald, “Xuan Zang’s records of the western regions.” Chinese Text Project. Accessed September 22, 2022.https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&res=944265&searchu=%E8%87%AA%E7%B4%A0%E5%8F%B6%E6%B0%B4%E5%9F%8E%E8%87%B3%E7%BE%AF%E9%9C%9C%E9%82%A3%E5%9B%BD%E3%80%82%E5%9C%B0%E5%90%8D%E7%AA%A3%E5%88%A9%E3%80%82&remap=gb.

[8]. Sturgeon Donald, “Book of Later Han.” Chinese Text Project. Accessed September 22, 2022. https://ctext.org/hou-han-shu/xi-yu-zhuan/zhs?searchu=%E6%A0%97%E5%BC%8B%E5%9B%BD%E5%B1%9E%E5%BA%B7%E5%B1%85%E3%80%82%E5%87%BA%E5%90%8D%E9%A9%AC%E7%89%9B%E7%BE%8A%EF%BC%8C%E8%92%B2%E8%90%84%E4%BC%97%E6%9E%9C%EF%BC%8C%E5%85%B6%E5%9C%9F%E6%B0%B4%E7%BE%8E%EF%BC%8C%E6%95%85%E8%92%B2%E8%90%84%E9%85%92%E7%89%B9%E6%9C%89%E5%90%8D%E7%84%89&searchmode=showall#result.

[9]. Vaissiere de La ,Etienne. (2018). Sogdian traders: a history. trans Jame Ward (Boston, 2005).

[10]. Yoshida Y, Moriyasu T, and Xinjiang Museum, “Sogdian Contract for the Purchase of a Slave Girl from the Era of the Kara-Khoja State of the Qu Clan,” Nairiku ajia gengo no kenkyu (Study of inland Asian languages) 4 (1988) 1–50

[11]. Yoshida Yutaka, The Sogdian Merchant Network, Teikyo university, Research institute of cultural properties, (article published online:2021),https://oxfordre.com/asianhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277727-e-491, accessed 22, 9, 2022

[12]. N Cosmo, DI., & M. Maas. (Eds.). Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity: Rome, China, Iran, and the Steppe, ca. 250–750. (Cambridge:2018)

[13]. Mary Boyce, "On the Zoroastrian Temple Cult of Fire", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 95 (3) (1975), 454-465

[14]. Mary Boyce, Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, (London:2000)

[15]. Sturgeon Donald, “The Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang ” Chinese Text Project, accessed September 22, 2022,https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=en&res=895322&searchu=%E8%84%82%E8%8B%8F%E6%B6%82&remap=gb.

[16]. Bo qing Jiang, Tang sancai Ceramicses from tome of General Anti ‘ the gods that were carried everywhere’ ——— a discussion on Sogdian Zoroastrianism belief , Chinese edition, Tangyanjiu (Chinese journal of Tang research) Vol: 7

[17]. Helan Wang, Money on the Silk Road, (London:2004)

[18]. Sturgeon Donald. “Jiu Tangshu.” Chinese Text Project. Accessed September 22, 2022. https://ctext.org/library.pl?if=gb&file=61171&page=45&remap=gb#%E6%97%A7%E4%BE%8B%E7%AC%AC%E4%B8%80%E5%86%9B%E7%BB%A2%E4%BA%8C.

[19]. Hanse Valerie, The place of coins and their alternatives in the Silks road trade, Chinese edition,in proceedings of the Symposium on ancient coins and the culture of the silks road. (Shang Hai :2011)