1.Introduction

Almost everyone has seen the famous photo: the soldier bending over the woman and kissing her to celebrate the end of the war. It’s one of the most famous photographs in American history, representing a spirit of national jubilation. But what else does it show? The end of World War II marked a new era in the United States. The country experienced economic growth, technological innovation, and demographic shifts that transformed its society and values. The media played a vital role in shaping and reflecting the culture and identity of the postwar era, especially about gender and sexuality. In this essay, I will show that in the most important visual culture artifacts of the 1940s, women were perceived as mothers or wives and as sex objects.

2.Secondary Source Analysis

Multiple historians have studied this issue in recent years. For instance, the article Post World War II: 1946-1970 published on the website Striking Women discusses how women resisted the unequal job opportunity and payment [1].

This source provides a useful overview of the context of women’s work during the postwar era, and how it was influenced by factors such as government policies, labor unions, consumer culture, and social movements. It also shows how women workers kept fighting for equal salary and better working conditions through strikes and protests, and how they faced discrimination and hostility from employers, male workers, and society at large.

Actually, some articles, such as Women in the 1950s by Khan Academy used statistics to prove that although some women continued to work after World War II [2], and the articles such as Women and Work After World War II by American Experience, PBS claimed that the rigid gender role still put shackles on many women [3]. In addition, Bridget O’Keefe in her article "Happiness, Womanhood, and Sexualized Media: An Analysis of 1950s and 1960s Popular Culture" delves into how media outlets perpetuated gender stereotypes. She argues that particularly by sexualizing and commodifying women, media outlets promote the idealized image of women as contented homemakers [4].

3.Methods

However, it is very rare for someone to analyze it visually. Thus, in this essay, I will use historical and visual analysis to prove that the female rights women earned at that time had some limitations, which means that there were still stereotypes of women’s roles and the sexualization of women in propaganda. I will use historical analysis to analyze why did it appear at the time after World War II and visual analysis to interpret the two primary sources, which are the poster of Coca-Cola and the V-J Day in Times Square photo.

4.Primary Source Analysis

4.1.Poster for Coca-Cola

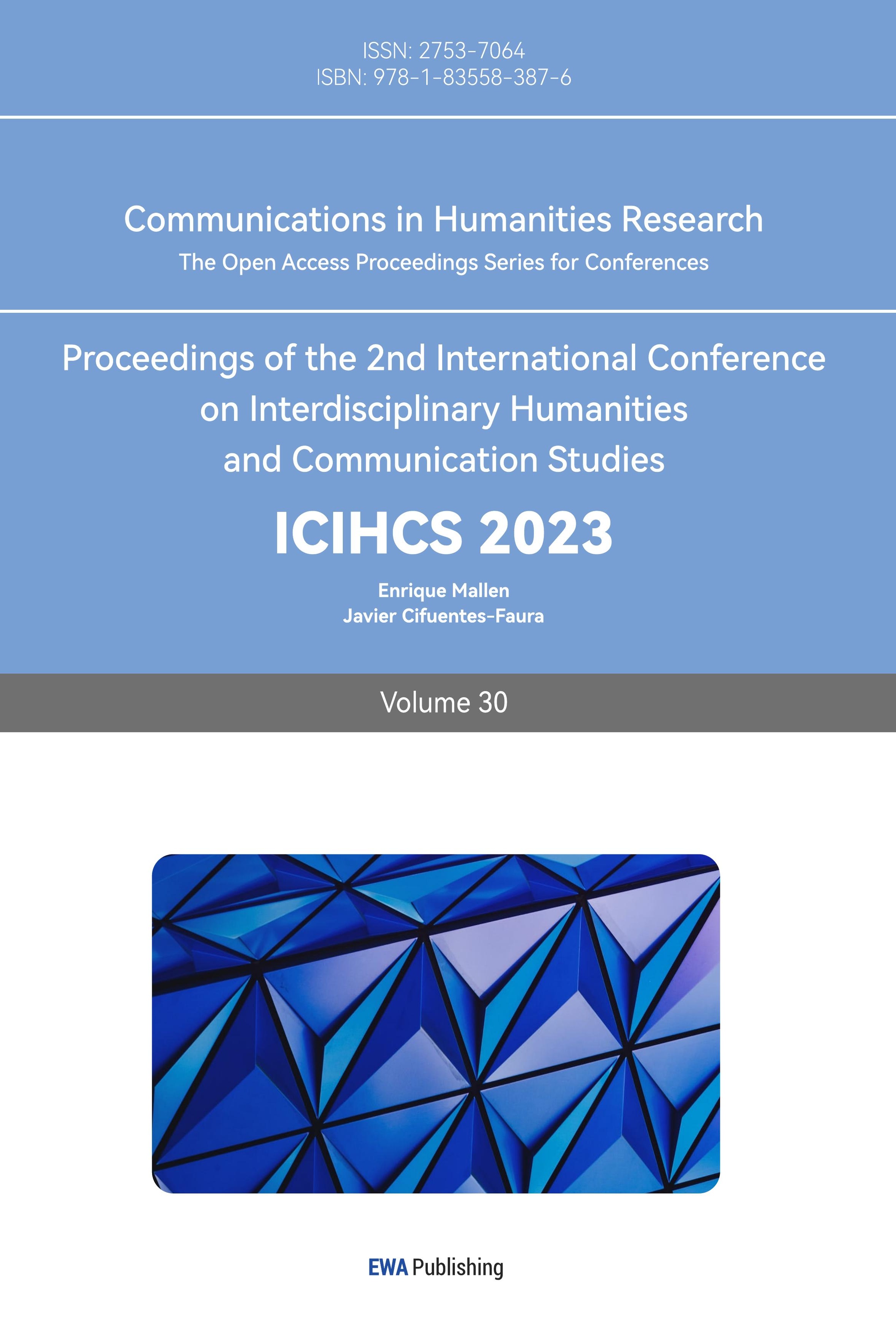

Figure 1: "He's coming home tomorrow" [5]

The first primary source that is going to be analyzed is the poster of Coca-Cola, which is about the way that women were often portrayed as maternal figures—even though, in practice, many of them were working in factories. This poster is part of a series of advertisements that celebrated the termination of the global conflict in 1945 and the return of soldiers. The central image depicts a woman carrying a child in her arms while pulling a baby carriage filled with Coca-Cola and other food items. The woman in the poster is dressed modestly and appears to be smiling brightly. A caption accompanying her image reads: "he is coming home tomorrow." The scene is set on a peaceful road, basked in warm and gentle sunshine, evoking a sense of relaxation and comfort.

This poster was created in 1944 by an unknown American artist. The poster was designed to evoke the emotions of hope, love, and loyalty among the American public. The poster also promoted Coca-Cola as a symbol of American culture and values. The “he” in the poster represents the soldiers who have returned from the battlefields of World War II. The woman in the poster symbolizes their idealized symbol of a wife: loyal, decent, caring, and considerate. As an advertisement, this poster aimed to resonate with the mass audience, and in doing so, it reflects the prevailing societal norms and expectations of that era. The ideal portrayal of women depicted in the poster aligns with traditional gender roles, where women were often seen as caretakers of the family, despite the reality that many of them were working in factories during the war. The poster reinforces the notion that women should prioritize their roles as mothers and caregivers, emphasizing their submission to their husbands.

This poster not only complies with the imagination of soldiers, but also implies the expectation for women. During World War II, with a large number of men away at war, women played a crucial role in the workforce, taking on jobs that were traditionally reserved for men. However, as the soldiers returned home after the war, societal pressure increased for women to step back from their roles in the workforce and focus on family life. In addition, as “The Baby Boom” by Khan Academy mentioned, after their service in the war, soldiers sought solace in settling down with their loved ones, yearning for stability and the chance to embrace family life. The GI Bill benefits assured them of fair wages, opportunities for secure employment, and affordable housing, all contributing to the feasibility of starting and raising a family [6], women were encouraged to bore more children. As a result, women were forced to quit their job and focus on their families and bore and take care of their children. The woman on this poster is hugging a baby in her arm, which is suggesting that women’s “duty”—is—to return to their families, give birth to children, and take good care of their husbands and descendants. This behavior can accomplish men’s wants at the same time——they got their jobs back, and they got their wives to take care of them and born them a baby. This society's push for women to embrace their roles as mothers and caregivers contributed to the perpetuation of traditional gender norms in the postwar era.

4.2.VJ Day Times Square

Figure 2: "The Kiss" [7]

The second primary source that is going to be to analyzed is V-J Day in Times Square photo. Within the lively ambiance of a crowded street, a U.S. Navy sailor is seen embracing and affectionately kissing a woman elegantly dressed in white attire in this photograph. The TIME magazine that first published this photo described that A white-clad girl stands in the heart of New York's Times Square, tightly holding her purse and skirt, while an unrestrained sailor boldly kisses her on the lips [8]. People around them were cheering and some of them were staring at them with joyfulness.

This photo was taken on August 14, 1945, when the announcement of the United States' triumph in World War II over Japan was made. It became very famous after it was first published in TIME magazine. There are even many couples imitating the posture of how the two main characters in this photo were kissing because it seems very elegant and romantic. The man was hugging and kissing the woman in a dominant position, and the woman was in a submissive position to accept and endure the kiss the man gave her. The sailor also represents the male hero who fought for his country and the nurse represents the female caregiver who tended to the wounded. As the analysis of the poster of Coca-Cola shows, there was a strong patriotism effect and stereotypes of gender roles and norms of the time. It would be a possible explanation for why this photo became so famous.

However, the photo of the VJ Day Times Square kiss became ironic when the true identities and stories of the kissers were revealed. Contrary to the popular perception that the sailor and the nurse were a couple or at least knew each other, they were actually strangers who never met before or after the kiss. The sailor, George Mendonsa even had a girlfriend at Times Square with him at that time named Rita Petry [9]. The nurse, Greta Zimmer Friedman, was a dental assistant who was grabbed and kissed by Mendonsa without her consent. Some details in the picture can prove that. The kissed “nurse” was not relaxing, and her arms were trying to defend and pull down her dress. The soldier’s arm was wrapped around her waist, forcing her into his embrace.

Interestingly, when the photo was first published, the article that was captioned by this photo had already revealed that “they [the men of war] ran the osculatory gamut from mob-assault upon a single man or woman, to indiscriminate chain kissing. Some servicemen just made it a practice to buss everyone in skirts that happened along, regardless of age, looks or inclination. [10]” But why did this photo turn out to be a romantic scene after WWII? The first possible reason is that the position of the two main characters fits the stereotype of dominant and submissive relations in gender, like how it was showcased in Coca Cola poster. Another possible reason is the victory of war eclipsed the offensive nature of this behavior.

Later revelations about the photograph confirm the impression that it was not a happy, consensual moment. The article titled "WWII’s most iconic kiss wasn’t romantic. It was assault" recounted how she expressed in a later interview that the kiss was not consensual, stating, "It wasn't my choice to be kissed. The guy just came over and grabbed!" When asked about her thoughts during that moment, she revealed, "I hope I can breathe. I mean, someone much bigger and stronger, where you've lost control of yourself, I'm not sure that makes you happy. [11]" As the #MeToo movement and increased awareness of consent and boundaries have reshaped our understanding of relationships and human interactions, the photograph's interpretation has evolved. In today's context, this act would be recognized as a clear case of assault, because George was drunk when he was kissing a girl he never met without her consent. The revelation of the true nature of the kiss raises important questions about the glorification of certain moments without fully understanding the context behind them. The photo, which was meant to symbolize love and victory, turned out to be an example of sexual assault and infidelity.

5.Conclusion

Re-examination of this iconic photo and coca cola poster, coupled with insights from secondary sources, paints a nuanced and multifaceted picture of women's experiences in the post-World War II era. While the secondary source suggests that women gained more rights due to increased opportunities for education and equal pay, a closer examination of primary sources reveals the persistent presence of gender stereotypes, sexualization, and commodification of women. The post-World War II era serves as a critical period for examining the evolving roles of women in society. While there were advances in women's rights, it is evident that gender stereotypes and sexualization persisted. By acknowledging these complexities and striving for progress, we can pave the way for a more just and inclusive world for all genders.

References

[1]. “Post World War II: 1946-1970,” Striking Women, accessed July 24, 2023, https://www.striking-women.org/module/women-and-work/post-world-war-ii-1946-1970.

[2]. “Post World War II: 1946-1970,” Striking Women. “Women in the 1950s,” Khan Academy, accessed July 24, 2023, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/us-history/postwarera/1950s-america/a/women-in-the-1950s.

[3]. “Women and Work After World War II,” American Experience, PBS, accessed July 24, 2023, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/tupperware-work/.

[4]. Bridget O’Keefe, “Happiness, Womanhood, and Sexualized Media: An Analysis of 1950s and 1960s Popular Culture,” New Errands: The Undergraduate Journal of American Studies 2, no. 1 (Fall 2014), https://journals.psu.edu/ne/article/view/59261.

[5]. Coca-Cola Company, “He’s Coming Home Tomorrow,” poster, 1944, https://www.pinterest.com/pin/223983781441271694/

[6]. The GI Bill is a law that provides various benefits to veterans of World War 2 and other wars. “The Baby Boom,” Khan Academy, accessed July 24, 2023, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/us-history/postwarera/postwar-era/a/the-baby-boom.

[7]. Alfred Eisenstaedt, “V-J Day in Times Square,” photograph, Time, August 27, 1945, 27, https://time.com/4486812/wwii-kiss-photo-vj-day/.

[8]. “The Kiss,” Time, August 27, 1945, 27

[9]. Lawrence Verria and George Galdorisi, “The Story Behind the Famous Kiss,” Naval History Magazine 26, no. 4 (July 2012), https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2012/july/story-behind-famous-kiss.

[10]. “The Kiss,” 27.

[11]. Kimble James C. and Tammy A. Plummer, “WWII’s most iconic kiss wasn’t romantic. It was assault.,” Washington Post, February 22, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/02/22/wwiis-most-iconic-kiss-wasnt-romantic-it-was-assault/.

Cite this article

Fang,C. (2024). Women in Post-World War II America: Portrayals, Stereotypes, and Challenges. Communications in Humanities Research,30,1-5.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. “Post World War II: 1946-1970,” Striking Women, accessed July 24, 2023, https://www.striking-women.org/module/women-and-work/post-world-war-ii-1946-1970.

[2]. “Post World War II: 1946-1970,” Striking Women. “Women in the 1950s,” Khan Academy, accessed July 24, 2023, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/us-history/postwarera/1950s-america/a/women-in-the-1950s.

[3]. “Women and Work After World War II,” American Experience, PBS, accessed July 24, 2023, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/tupperware-work/.

[4]. Bridget O’Keefe, “Happiness, Womanhood, and Sexualized Media: An Analysis of 1950s and 1960s Popular Culture,” New Errands: The Undergraduate Journal of American Studies 2, no. 1 (Fall 2014), https://journals.psu.edu/ne/article/view/59261.

[5]. Coca-Cola Company, “He’s Coming Home Tomorrow,” poster, 1944, https://www.pinterest.com/pin/223983781441271694/

[6]. The GI Bill is a law that provides various benefits to veterans of World War 2 and other wars. “The Baby Boom,” Khan Academy, accessed July 24, 2023, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/us-history/postwarera/postwar-era/a/the-baby-boom.

[7]. Alfred Eisenstaedt, “V-J Day in Times Square,” photograph, Time, August 27, 1945, 27, https://time.com/4486812/wwii-kiss-photo-vj-day/.

[8]. “The Kiss,” Time, August 27, 1945, 27

[9]. Lawrence Verria and George Galdorisi, “The Story Behind the Famous Kiss,” Naval History Magazine 26, no. 4 (July 2012), https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2012/july/story-behind-famous-kiss.

[10]. “The Kiss,” 27.

[11]. Kimble James C. and Tammy A. Plummer, “WWII’s most iconic kiss wasn’t romantic. It was assault.,” Washington Post, February 22, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/02/22/wwiis-most-iconic-kiss-wasnt-romantic-it-was-assault/.