1. Introduction

In 1939, the world entered a nightmare as World War II began. Initially, Japan and the Japanese did not suffer much from this war, but by 1944, devastating bombings by the United States military brought unparalleled suffering to Japanese citizens. These bombings left vast areas desolate and claimed the lives of thousands. Within this context, two prominent artists, Murakami and Nara, have played pivotal roles. Their artwork serves as a window through which we can explore the impact of the bombings and World War Two on the post-war generation in Japan. In this research, I delve into their childhoods, family backgrounds, educational experiences, and international acclaim to understand their influence on the world and the connection of their works to World War Two. Furthermore, this study seeks to uncover how the Japanese people perceive themselves in the war and how they recall or face the traumatic impact of the bombings. In this work, I conduct a detailed analysis of the results of artists Murakami and Nara while contextualizing them within the broader social background in Japan.

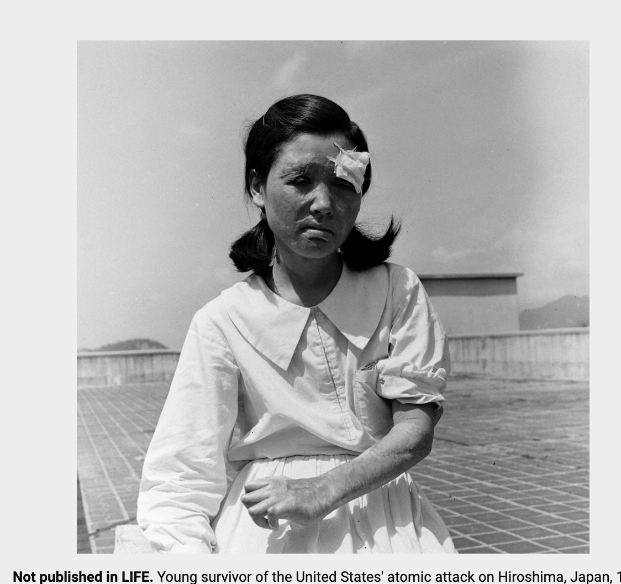

Seventy-eight years ago, the world suffered from a big turmoil war that started in 1939 (when WW2 started) and lasted until 1945 (when WW2 ended). Life before the bombing happened in 1944 was a climax time for Japanese citizens. People believed that with the help of Amaterasu, Japan was successfully turning into a ruling country. Japanese people celebrated their Meiji constitution and were very proud to be Japanese. However, life completely changed in August 1945 when the two atomic bombs were dropped on Japan by the American Army, bringing an end to the Second World War. Using two bombs, America completely devastated Japanese prosperity, setting them back to ancient times and erasing centuries of glory in just one night. According to Mark Selden, the horror of the bombing began in March 1945 when 334 B-29 bombers targeted Tokyo with incendiary bombs, creating massive firestorms that killed millions of residents [1]. Consequently, 87,793 people in Japan died, 40,918 were injured, and 1,008,005 lost their homes. From January to July 1945, the United State’s firebombing obliterated nearly all Japanese cities except Kyoto and four other cities, which were deliberately spared (Figure 1, 2).

Figure 1: survivors of the bomb but got seriously hurt and usually die in one year or less than one year due to the radiation of the bomb (Cosgrove) [2]

Figure 2: This is what it is like after the bomb. Almost everything got destroyed ((“The Most Fearsome Sight: The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima”) [3]

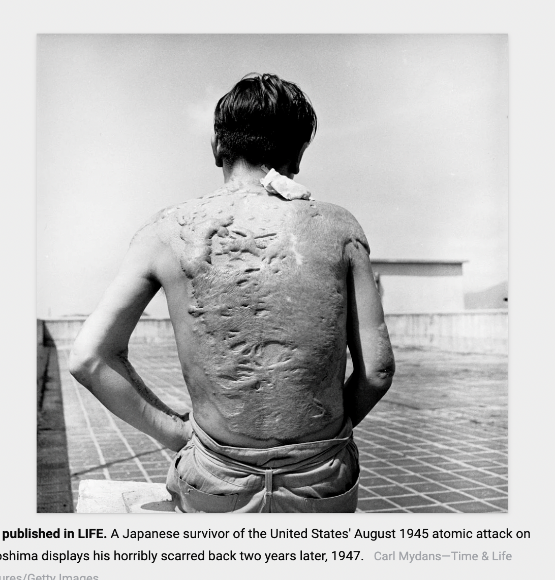

After Japan's surrender on September 2nd, the Japanese government focused entirely on finding ways to regain prosperity and restore the economy as quickly as possible. According to Chapter 6 of the book "Bodies of Memory," during this period, Japanese people worked longer hours to improve their living conditions, and some worked in impoverished circumstances [4]. This led to one of the main concerns at that time: Karo-Jisatsu and Karoshi. According to a report, between 1950 and 1960, right after World War II, Japan had the highest suicide rate throughout Japan's history [5]. In the other two reports, the authors examined multiple reasons that might have contributed to the ongoing rise in the Japanese suicide rate and death rate, with particular emphasis on deaths caused by overwork [6] [7] (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Suicide rate chart (The dots here represent various age groups, with the square box representing the age range with the highest suicide rate, which is 15-24 years old.)

Karo-Jisatsu is a term that technically refers to suicide caused by overwork, and Karoshi is a broader term referring to death caused by overwork. Although the reasons leading to these two phenomena may vary, they were all primary causes of the postwar effect. The postwar generations in Japan needed to work longer hours and extra hard to regain prosperity. Additionally, people's reactions toward rapid change, rebuilding, hopelessness, and cultural reflection after World War Two made depression and suicide common phenomena, which the suicide rate in Japan can prove. Artists Yoshitomo Nara and Takashi Murakami can act as representatives to present people’s fear and anxiety after that period.

2. Artists Yoshitomo Nara and Yakashi Murakmi

In this paper, I first analyzed the aftermath of the atomic bombing in World War Two, which profoundly impacted subsequent social and cultural changes. To provide a deeper understanding, I examined the works of two prominent post-war generation artists, Yoshitomo Nara and Takashi Murakami, who serve as a window to interpret prevailing conditions. I selected one representative work from each artist to perform close visual and contextual analysis. By interconnecting these various sources, I argue that these artworks have opened up a window into the inner world of the people grappling with mental crises and recovering from the trauma in post-war Japan. As my evidence, I combined both primary sources and secondary sources. My primary sources are my interpretation and visual analysis of the artworks chosen. This provides us with basic information that is crucial in understanding the theme. My secondary sources include a range of university studies, artists' biographies, economists' analyses, and connoisseurs' works. These works are essential in providing a contextual solid background and professional analysis, helping me to delve into my research topic.

2.1. Yoshitomo Nara

Yoshitomo Nara was a Japanese artist born in 1959 in Hirosaki, Aomori Prefecture, Japan [8]. He lived near a US Air Force base and witnessed the changes brought by the impact of World War II on Japan from a young age. Additionally, due to the social background of overwork, his parents were very busy and rarely around since he was small; thus, he spent most of his time alone, resulting in a sense of loneliness from an early age [9].

Nara’s works can be split into three parts. His work begins by centering around the impact of his childhood, initially focusing on depicting a young child and then gradually expanding to a more intricate context. This approach unveils not only his childhood impact but also sheds light on the social backdrop of postwar Japan.

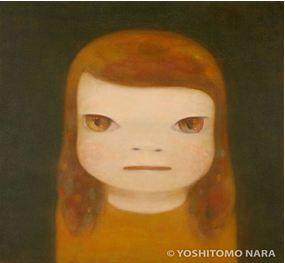

As he started his artistic journey, he began portraying images of a little kid, drawing inspiration from his childhood experiences. Children in his artwork are often depicted with elongated, narrowed eyes. Unfocused pupils in the eye seem empty, expressing a feeling of loneliness and confusion, which delivers a conflicting emotion against the cute and innocent figures depicted. The appealing object appears soft, round, and vulnerable, inviting physical touching. Still, it can also evoke aggressive feelings and sadistic desires for control due to the child’s innocent and naïve expression, which may be perceived as foolishness in their eye contact. He often portrays cute, naive children figures with a knife or other dangerous tools next to them, challenging the notion of "kawaii" [10]and its association with naivety while also exploring themes of depression and anxiety (Figure 4).

Figure 4: The Girl with the Knife in Her Hand (“The Girl with the Knife in Her Hand”) [11]

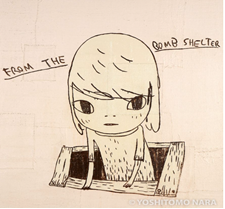

After disasters such as the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami in Japan, Nara, in his early 50s, started focusing more on politics and tragedies in Japan. Growing up near an Air Force Base, he also drew inspiration from his childhood. Observing the soldiers' training and hearing about the harsh conditions and reality faced by those involved in World War II helped Nara comprehend the extent of suffering endured by the Japanese population during the bombings and the war [12]. He got lost sometimes after this period of his career, but later on, he started to incorporate elements from both stages together. The picture “From the Bomb Shelter” is one of his later works.

Figure 5: From the Bomb Shelter (“From the Bomb Shelter”) [13]

This work is done on a canvas measuring 180.5 x 160.5 x 4.8cm, and it is a monogram (Figure 5). The artist depicts a female child figure in the center of the canvas. The child's proportions are not correct, as if Nara deliberately focused on enlarging the child's head. The artist also seems to be inspired by minimalism, depicting the figure in a simplistic way that makes her stand out from the bomb shelter. The figure has enlarged eyes that stare directly at the audience, with a circular nose and an oval-shaped mouth. There are also words behind her head, on the canvas, that refer to this work's title, providing context for interpreting this painting. This work continues the design of Nara's early works of depicting a child but also departs from his previous work by adding a more intriguing contextual background.

By referring to the "bomb shelter" in both the title and the artwork, the artist places this child in the context of World War Two. Behind the naive pair of eyes staring directly at the audience, it reveals the fear, anxiety, and confusion experienced by this character. When creating this work, Nara was influenced by the movie "Hiroshima," a film from 1953 that addresses the theme of the atomic bombing and reflects on its postwar impact. Nara's reference to the nuclear bombing and his own childhood experiences in this piece represents his political point of view. It expresses innocence and anxiety toward post-war Japan [14].

2.2. Takashi Murakami

Takashi Murakami, born in the same generation as Yoshitomo Nara, is also a prominent artist associated with the 'Superflat' artistic movement. This movement emerged in Japan during the early 2000s and is defined by its emphasis on flatness and a lack of depth in art, symbolizing the superficiality prevalent in post-war Japanese society and culture. This artistic movement draws inspiration from Japan's 'flat' aesthetic. It features bold, exaggerated outlines similar to cartoons and employs flat colors, lacking natural depth. According to the website “The Art Story”, Murakami was born on February 1, 1962, in Tokyo, Japan [15]. Unlike Nara’s childhood, Murakami grew up with his parents forcing him to look at art galleries and write quick, short notes for them. His childhood experience and how his parents forced him to go to art exhibitions from small were key factors that led him to step into the artistic world and develop an aesthetic style that allowed him to create artwork quickly and at high quality. One phrase he heard the most while growing up was: “If the U.S. dropped another nuclear bomb, you would not have been born.” This phrase profoundly impacted him and made him reflect on the war's impact on his entire life and through his artistic innovations.

In his art career, he was inspired by Andy Warhol's work, and he kept on seeking the relationship between commercial and art, as well as between high art and low art. The majority of his work is presented animatedly and is used in a variety of different contexts. Still, primarily, he keeps using art to allude to the pressure in Japanese hearts or the suffering that happened to Japan after the bomb.

Figure 6: Takashi Murakami Flowers, Flowers, Flowers (“Takashi Murakami Flowers, Flowers, Flowers, 2010”) [16]

This is one of Takashi Murakami's most representative artworks (Figure 6). The work is done on a canvas that measures 149.9 × 149.9 cm. It features numerous repetitive flowers with smiling faces. These flowers cluster together with no specific pattern and in different sizes. Some hide behind others, while some pop out toward the artist. No particular color tone is used; various colors are employed without being mixed and dissolved into one another. The occupation of the flowers is so intense that it does not leave out any white space on the canvas.

At first glance, the repetition of smiling and cheerful similes on these flowers creates a bright tone. However, beyond their positive appearance lies a deeper meaning. Looking at them for an extended period, one can feel how these cheerful similes may ironically imply a sad and anxious feeling. The dense crowd of flowers makes people feel breathless, and each smile on the flowers is in perfect proportion and size. While some flowers overlap and some seem closer to the audience, the smiling on the flower appears superficial. It presents a false appearance of calmness and optimism that the Japanese may act out toward the outsiders. Murakami explains that the smiling faces of the flowers symbolize the repressed collective emotions of Japanese locals who suffered from the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings in 1945 [17]. Just like how people in the post-war period mask the suffering people went through during the war, Murakami is also burying his intentions to express the oppression the post-war generation feels beneath the surface and alludes to the audience in a more metaphorical way [17]. This way of expressing can also be traced back to the Japanese traditional aesthetic value of presenting descent and veiled meaning to outsiders while keeping the real feelings and intentions reserved for family and themselves. In his work, Murakami has spent a lot of time exploring the post-war relationship between the United States and Japan. He believes that the best way to spread the idea of the war's impact to the public is through commercialization and influence from pop art design and culture, thus creating these iconic motif flowers.

2.3. Traditional Culture and Background Study

By aiming to spread their contextual intention more, the two artists have earned global fame, but the core concept of their works still preserves and is greatly influenced by traditional Japanese culture. For example, Nara's works' motifs and themes are closely linked to the ideas of Buddhism and Shinto beliefs. As his grandfather was a Shinto priest, he grew up gradually familiarizing himself with these principles and drawing inspiration from them. According to the report by Suerth, the writer introduced Nara’s painting "Midnight Surprise," emphasizing how it was influenced by certain Buddhist principles (“Midnight Surprise”) [18].

Figure 7: Midnight Surprise

The main focus of this artwork isn't just the subject matter of a little girl staring directly at the audience, but it's also about the layers of paint that have been built up on the canvas (Figure 7). The audience can hardly see any apparent brushstrokes when looking at the painting. Everything seems smooth, and colors seem to defuse into one another. This feeling of smoothness was done by applying layers and layers of paint. The layers of paint signify depth and continual contemplation while creating this work, allowing the viewer and the artist to think deeply about themselves and reflect on their own being. This idea is connected with the core concept of meditation in Zen Buddhism. His other artworks, like the one below, usually present an innocent child figure holding dangerous weapons in their hands [19]. In this painting, the knife can allude to the idea of death, focusing on Shinto and Buddhism's ideas toward death and the afterlife. In traditional Shinto belief, people believe that when a person dies, their spirit survives and continues to exist even though their body is physically deceased. However, Hara's work never precisely answers what he thinks about death and the afterlife. Instead, he alludes to these ideas and principles in creating his artworks while also reflecting on the loneliness and depression he felt during his childhood due to the separation from his family.

Figure 8: “Nice to See You Again”

Murakami also shows the influence of Japanese traditional culture in his artistic creations (Figure 8). This influence can be traced back to his academic studies as an artist, during which he spent about 11 years studying Japanese Nihonga painting in his early artistic journey. However, after establishing a solid foundation, he felt it was not enough to simply spread Japanese culture and the message he wanted to convey about Japan to the world. In order to gain more impact and learn more, he went to the West to pursue further studies and found great inspiration in Andy Warhol's artworks there.

He combined traditional Japanese artistic styles, such as flatness, with Western contemporary styles, such as pop culture, developing his unique art styles and designs. This fusion allowed his artwork to exhibit the characteristics of the traditional Japanese animation style and flatness while still producing the idea of mass production. Thus, his paintings have a feature that seems to fit in every context, and in each different setting, they convey distinct and unique meanings. Much like Andy Warhol, Murakami employed mass production techniques to erase the boundaries between high art and low art, emphasizing the rapid changes in the world and how consumers now pursue and create a more productive society [20].

2.4. International Fame

Although they have earned massive international fame, their artistic style and the context of their works still refer to Japan's motifs. Both artists' works mostly allude to the bomb and the ideas of depression and anxiety. Though never depicted realistically, the smiles on the sunflowers and the innocent child faces carry meanings that reflect the contemporary struggles with depression and anxiety among the post-war generation. These issues were largely caused by the bomb and the post-World War Two lifestyle. Understanding this context, studying these two artists' commercial and international influence becomes very intriguing. Why were people outside Japan influenced and shocked by these two artists’ works? Why do both arts have such a profound impact commercially?

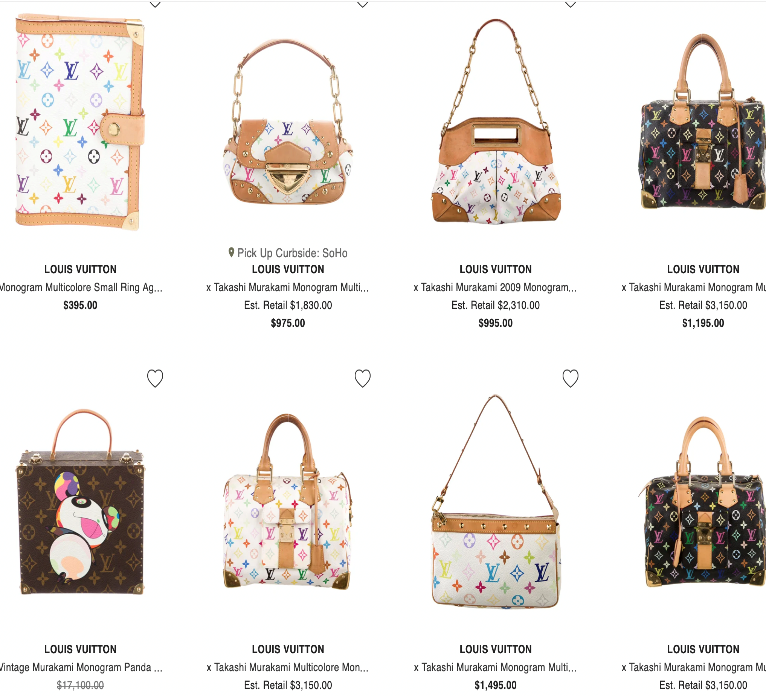

Louis Vuitton is a luxury brand with a massive significant influence. Murakami is one of Louis Vuitton's most influential collaborators. Together, they have created enormous commercial value and elevated art to a new level, reflecting the relationship between art and commerce. According to the report by Xiaoming Hu, Murakami's primary message behind his artwork was to convey the suffering of the Japanese during World War Two's bombings [21]. However, it was challenging for Murakami to resonate with people outside of Japan and convey the meaning of the bombings to them. Through his cooperation with Louis Vuitton, Murakami gained fame and metaphorically gave his message to a broader audience. Based on another report, one of the reasons why this cooperation has lasted long and been so successful is how Murakami designed symbols and artwork that can be universally appealing [22]. By incorporating the LV logo, he presents familiar paintings to the audience in a way that specializes in the Louis Vuitton brand. This approach has helped Louis Vuitton gain recognition distinct from any other luxury brand and has increased its commercial value. Simultaneously, it promoted Murakami's art and the messages he aimed to convey (Figure 9).

Figure 9: LV’s website (Lious Vuitton and Murakami’s cooperation’s works) (“Louis Vuitton”) [23]

Nara and Murakami have also gained international recognition and fame in art [24]. In this book, the writer discusses various artists. Still, the primary focus remains on Yoshitomo Nara and Takashi Murakami and how their styles contributed to developing the "superflat" art movement. Both Nara and Murakami initially participated in the "Cool Japan" movement, which aimed to blend traditional Japanese culture with Western aesthetics and ideals. However, they soon realized that Japan's art market was insufficient for their work to stand out and profoundly impact the modern world. After the natural disasters in Japan in 2011, the "Cool Japan" era ended. In response, both artists started the art movement of "superflat." Works in “super flat," as the name suggests, primarily focus on using simplified and two-dimensional paint techniques. Through this movement and incorporating Western influences, such as mass production and other processes, they sought to redefine their roles as artists and create a more sustainable vision for Japanese art. Furthermore, through the global exhibition of their works, the two artists convey their perspectives on the impact of the World War Two bombings. As their work and fame reach an increasingly wider audience, it exposes their original creative concepts and the innovative context behind these works more to audiences. This way, the artists continue to guide the audience to reflect upon the disaster and help people outside of Japan understand the significance of the bombing and its impact on the Japanese in an alluring way.

3. Conclusion

In summary, as representatives of Japan's postwar generations, Nara and Murakami depict the aftermath of the bombing and its connection to depression and anxiety. These emotions are universally relatable, resonating with people worldwide. This influence aided them in attaining international fame, and through commercial appeal, they could further propagate their ideas and values. The limitation of this research paper is that secondary research sometimes lacks direct references to the specific question I am researching. As a result, I need to search for more research on a wide variety of views on one topic. In the future, with more time and additional resources, there is potential for a deeper analysis of the connection between art and commerce and the contemporary meaning of art.

References

[1]. Selden, Mark. “A Forgotten Holocaust: US Bombing Strategy, the Destruction of Japanese Cities & the American Way of War from World War II to Iraq.” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 2 May 2007, apjjf.org/-Mark-Selden/2414/article.html

[2]. Cosgrove, Ben. “After Hiroshima: Portraits of Survivors.” Time, 20 Mar. 2014, time.com/3879427/hiroshima-portraits-of-survivors/feed/. Accessed 24 July 2023.

[3]. “The Most Fearsome Sight: The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima.” The National WWII Museum | New Orleans, 6 Aug. 2020, www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/atomic-bomb-hiroshima.

[4]. Igarashi, Yoshikuni. Bodies of Memory. Course Book ed., 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540, Princeton University Press, p. 304, www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9781400842988/html.

[5]. Araki, Shunichi, and Katsuyuki Murata. Suicide Mortality in Japan: Analysis of the Unusual Secular Trends. Department of Public Health and Hygiene.

[6]. Yuko, Kawanishi. “On Karo-Jisatsu (Suicide by Overwork): Why Do Japanese Workers Work Themselves to Death?” Taylor and Francis, Ltd.

[7]. Nabeshima, Yuri Kuroda. “KAROSHI” Comparative Overview of Brazilian and Japanese Law Related to Karoshi. pp. 243–264.

[8]. Ivy, Marilyn. “The Art of Cute Little Things: Nara Yoshitomo’s Parapolitics.” Mechademia, vol. 5, pp. 3–29, www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/41510955.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%25253A5ba5350cce118d6d30deb0f57dc1682b&ab_segments=0%25252Fbasic_search_gsv2%25252Fcontrol&origin=&initiator=&acceptTC=1. Accessed 24 July 2023.

[9]. Nara, Yoshitomo. Yoshitomo Nara: Self-Selected Works-Paintings. 1st ed., 9-1, Umetada-cho, Nakagyo-ku, Kyoto 604-8136 Japan, Seigensha Art Publishing, Inc., 2015.

[10]. Suerth, Sawyer. Yoshitomo Nara - Heritage and Curation

[11]. “The Girl with the Knife in Her Hand.” SFMOMA, www.sfmoma.org/artwork/99.132/.

[12]. “Yoshitomo Nara - 20th Century & Contemporary Art Evening Sale in Association with Poly Auction Hong Kong Tuesday, June 8, 2021.” Phillips, www.phillips.com/detail/yoshitomo-nara/HK010121/18. Accessed 11 Sept. 2023.

[13]. “From the Bomb Shelter.” YOSHITOMO NARA the Works, 2017, www.yoshitomonara.org/en/catalogue/YNF6433/. Accessed 24 July 2023.

[14]. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “Yoshitomo Nara – Part 3: No Longer Just a Girl with a Knife: Art after Fukushima | Art & Conversation.” Www.youtube.com, 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=MVuLK6aA6C8&t=2358s. Accessed 11 Sept. 2023.

[15]. “Takashi Murakami.” The Art Story, www.theartstory.org/artist/murakami-takashi/.

[16]. “Takashi Murakami Flowers, Flowers, Flowers, 2010.” Artsy, www.artsy.net/artwork/takashi-murakami-flowers-flowers-flowers-4. Accessed 24 July 2023.

[17]. HYPEBEAST. “The Hysteria of This Flower Explained | behind the HYPE: Murakami’s Flowers.” Www.youtube.com, 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=zPkAQCdXcLc&t=337s. Accessed 11 Sept. 2023.

[18]. “Midnight Surprise.” YOSHITOMO NARA the Works, www.yoshitomonara.org/en/catalogue/YNF6425/.

[19]. “Yoshitomo Nara Nice to See You Again.” Sotheby’s.

[20]. Luke, Ben. Takashi Murakami. artecontemporáneo gacma, 2007.

[21]. Hu, Xiaoming. Is Takashi Murakami’s Art an Exploration of Symbolism?

[22]. Bengtsen, Peter. Fashion Curating: Critical Practice in the Museum and Beyond. 2017. 1st ed., Bloomsbury Academic, 28 Dec. 2017, pp. 1–233.

[23]. “Louis Vuitton.” TheRealReal, www.therealreal.com/products?keywords=Louis%20Vuitton%20Murakami. Accessed 26 July 2023

[24]. Favell, Adrian. Before and after Superflat. 19A Entertainment Building 30 Queen’s Road Central Hong Kong, Blue Kingfisher Limited, 2011, pp. 1–246.

Cite this article

Li,Z. (2024). How Art Has Been a Window to the Post-War Generation in Japan. Communications in Humanities Research,30,67-76.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Selden, Mark. “A Forgotten Holocaust: US Bombing Strategy, the Destruction of Japanese Cities & the American Way of War from World War II to Iraq.” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 2 May 2007, apjjf.org/-Mark-Selden/2414/article.html

[2]. Cosgrove, Ben. “After Hiroshima: Portraits of Survivors.” Time, 20 Mar. 2014, time.com/3879427/hiroshima-portraits-of-survivors/feed/. Accessed 24 July 2023.

[3]. “The Most Fearsome Sight: The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima.” The National WWII Museum | New Orleans, 6 Aug. 2020, www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/atomic-bomb-hiroshima.

[4]. Igarashi, Yoshikuni. Bodies of Memory. Course Book ed., 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540, Princeton University Press, p. 304, www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9781400842988/html.

[5]. Araki, Shunichi, and Katsuyuki Murata. Suicide Mortality in Japan: Analysis of the Unusual Secular Trends. Department of Public Health and Hygiene.

[6]. Yuko, Kawanishi. “On Karo-Jisatsu (Suicide by Overwork): Why Do Japanese Workers Work Themselves to Death?” Taylor and Francis, Ltd.

[7]. Nabeshima, Yuri Kuroda. “KAROSHI” Comparative Overview of Brazilian and Japanese Law Related to Karoshi. pp. 243–264.

[8]. Ivy, Marilyn. “The Art of Cute Little Things: Nara Yoshitomo’s Parapolitics.” Mechademia, vol. 5, pp. 3–29, www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/41510955.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%25253A5ba5350cce118d6d30deb0f57dc1682b&ab_segments=0%25252Fbasic_search_gsv2%25252Fcontrol&origin=&initiator=&acceptTC=1. Accessed 24 July 2023.

[9]. Nara, Yoshitomo. Yoshitomo Nara: Self-Selected Works-Paintings. 1st ed., 9-1, Umetada-cho, Nakagyo-ku, Kyoto 604-8136 Japan, Seigensha Art Publishing, Inc., 2015.

[10]. Suerth, Sawyer. Yoshitomo Nara - Heritage and Curation

[11]. “The Girl with the Knife in Her Hand.” SFMOMA, www.sfmoma.org/artwork/99.132/.

[12]. “Yoshitomo Nara - 20th Century & Contemporary Art Evening Sale in Association with Poly Auction Hong Kong Tuesday, June 8, 2021.” Phillips, www.phillips.com/detail/yoshitomo-nara/HK010121/18. Accessed 11 Sept. 2023.

[13]. “From the Bomb Shelter.” YOSHITOMO NARA the Works, 2017, www.yoshitomonara.org/en/catalogue/YNF6433/. Accessed 24 July 2023.

[14]. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “Yoshitomo Nara – Part 3: No Longer Just a Girl with a Knife: Art after Fukushima | Art & Conversation.” Www.youtube.com, 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=MVuLK6aA6C8&t=2358s. Accessed 11 Sept. 2023.

[15]. “Takashi Murakami.” The Art Story, www.theartstory.org/artist/murakami-takashi/.

[16]. “Takashi Murakami Flowers, Flowers, Flowers, 2010.” Artsy, www.artsy.net/artwork/takashi-murakami-flowers-flowers-flowers-4. Accessed 24 July 2023.

[17]. HYPEBEAST. “The Hysteria of This Flower Explained | behind the HYPE: Murakami’s Flowers.” Www.youtube.com, 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=zPkAQCdXcLc&t=337s. Accessed 11 Sept. 2023.

[18]. “Midnight Surprise.” YOSHITOMO NARA the Works, www.yoshitomonara.org/en/catalogue/YNF6425/.

[19]. “Yoshitomo Nara Nice to See You Again.” Sotheby’s.

[20]. Luke, Ben. Takashi Murakami. artecontemporáneo gacma, 2007.

[21]. Hu, Xiaoming. Is Takashi Murakami’s Art an Exploration of Symbolism?

[22]. Bengtsen, Peter. Fashion Curating: Critical Practice in the Museum and Beyond. 2017. 1st ed., Bloomsbury Academic, 28 Dec. 2017, pp. 1–233.

[23]. “Louis Vuitton.” TheRealReal, www.therealreal.com/products?keywords=Louis%20Vuitton%20Murakami. Accessed 26 July 2023

[24]. Favell, Adrian. Before and after Superflat. 19A Entertainment Building 30 Queen’s Road Central Hong Kong, Blue Kingfisher Limited, 2011, pp. 1–246.