1.Introduction

The usage of memes has started to become common on the Chinese internet. On social media platforms and various video apps, memes have gradually become a unique form of expression. Because memes represent a collection of semantics or allusions, individuals need to understand the underlying meaning to grasp what those who use memes intend to convey. Therefore, the surface meaning of a meme and its actual significance create a particular information barrier, leading to people being divided into different groups based on whether they understand a specific meme.

Within these groups, people communicate in a language that outsiders may not comprehend. Consequently, I believe that these individuals might develop a sense of belonging to these groups. To explore whether there is a connection between meme usage and a sense of belonging, this paper conducted a survey.

2.Review

2.1.Meme

The term meme, a portmanteau of mimesis and gene, was minted in 1976 by British ethologist and evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins in his book The Selfish Gene (1976) [1]. To put it simply, a meme is a unit of information which is transmitted between people. Nowadays, memes are called "梗"(It's pronounced like "gěng“) in China. They mostly appear on various social media.

In One Does Not Simply: An Introduction to the Special Issue on Internet Memes, authors Laine Nooney and Laura Portwood-Stacer argue that a meme, in the context of Internet socialization, is a specific visual, textual or auditory based digital object that is then reinvented and appropriated to be reintroduced into Internet communication [2].

2.2.Role of Meme

Artist, journalist and cultural critic A Xiao Mina focuses on the power of memes, especially in the context of strict external censorship and control, such as in contemporary China. She argues that the ironic meanings inherent in memes can carve out a special space of privacy for the people who use them [3].

Limor Shifman treats photographic meme genres as ‘cultural keys’ that can unlock the logic of networked internet culture [4]. Her analysis identifies the ‘hypersignification’ present in photographic memes, showing how memes expose both the process of meaning-making inscribed in their own production, and the networked structure of the communities that form around them.

In sum, memes have a grouping effect on audiences in the process of dissemination, innovation and re-dissemination, in which the people who use a particular meme are divided into different groups, and in which a sense of belonging may play a role.

2.3.sense of social belonging

In The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation (Van Bel et al .2009), the hypothesis that the need to belong is a fundamental human motivation is proposed. Social connectedness is a “short-term experience of belonging and relatedness”. [5] (p.67) Their view portrays humans as born with an instinct to establish and maintain a sense of belonging, so that the need to belong will be present in humans of all cultures, although there will be some individual differences in the strength and intensity of the sense of belonging due to region and culture, as well as cultural and individual differences in how people express and satisfy this need. But culture is difficult or impossible to eradicate this sense of belonging (except perhaps for a small number of severely distorted individuals). The authors stated that “belongingness can be almost as compelling a need as food and that human culture is significantly conditioned by the pressure to provide belongingness” (p. 498)

People need to have frequent interactions and contacts with others (positive interactions), and they need to perceive the relationships and recognize that they are stable and will continue for the foreseeable future. Ideally, the relationship is mutual and therefore reciprocal. M.S. Clark and his colleagues have demonstrated that the relationships produced by a framework of mutual concern are fundamentally different from those produced by social change based on self-interest [6].

Linville and Jones (1980) showed that when confronted with information from out-group members, people tend to process it in an extreme, black-or-white, simplistic, and polarized way, whereas a more complex approach will be used with in-group members [7]. (Polarized appraisals of out-group members) Such differences in the way information is processed may strengthen the sense of belonging of members within a group, while at the same time reinforcing exclusion between groups.

2.4.Measurement of social belonging

In early studies such as Baumeister and Leary's 1995 article, the sense of belonging as an explanatory construct received much attention in the field of psychology. However, methods for assessing one's sense of belonging have evolved gradually. Hagerty and Patusky co-developed an instrument to assess general sense of belonging [8]. Lee and Robbins (1995) sought to develop an assessment instrument that was defined by three factors: peer relationships that included one-to-one contact, subordination to small groups, and connections to larger social collectives [9].

In The General Belongingness Scale (GBS) - Assessing achieved belongingness, Malone and David propose a short, broadly applicable measure (GBS) to measure achieved belongingness [10].

Research on measuring attribution has come a long way. Incorporating previous research and in order to examine aspects of the theoretical network surrounding individual differences in the need to belong, Mark R. Leary , Kristine M. Kelly , Catherine A. Cottrell & Lisa S. Schreindorfer, in Constructing Validity of the Need to Belong Scale: Mapping the Nomological Network, hope to more accurately explain individual differences in attributional motivation by assessing a number of listed motivational, affective, and behavioral characteristics, and conclude the article with a scale to measure attribution [11].

3.Methodology

The research methodology of this study employed a questionnaire survey approach, and the collected questionnaire data were analyzed using SPSS for quantitative analysis.

The survey questionnaire was created using wjx.cn (https://www.wjx.cn/) and could be directly distributed on China's most popular social media platform, WeChat. The survey's QR code was disseminated in WeChat group chats and on WeChat Moments, with multiple distribution channels to ensure that participants in the survey were drawn from various demographic groups as much as possible.

3.1.Survey Design

The content of this study focuses on the correlation between the use of memes on social media under the context of the Chinese internet and a sense of belonging. In the questionnaire, the third question is designed to determine whether the participants have encountered memes on social media. If they answer "no," the questionnaire terminates at that point. Gender and age of the participants might influence their usage of memes. Therefore, the first part of the questionnaire is aimed at collecting data on these aspects. The second part employs scale questions to gauge the extent of participants' daily use of memes, and the third part uses scale questions to measure the participants' sense of belonging while using social media.

All questions are presented in a single-choice format, allowing respondents to answer quickly, and participants receive a small monetary reward upon completing the questions.

3.2.Assumption

Given that individuals actively participate in the dissemination and innovation of memes, and assuming that individuals feel a sense of belonging to groups that use the same memes, it is hypothesized that, within the context of the Chinese internet, using, sharing, and innovating memes can evoke positive emotions. Therefore, measuring individuals' emotions during this process can provide a preliminary indication of whether they are likely to experience a sense of belonging. (If individuals experience negative emotions, it can be preliminarily assumed that they have not developed a sense of belonging during this process; if individuals experience positive emotions, it may be due to the influence of a sense of belonging and warrant further investigation.)

The hypothesis suggests that within the online community, people who use a large number of popular memes will be categorized into different groups based on the specific memes they use, and individuals will feel a sense of belonging to these groups. However, this sense of belonging is different from Baumeister and Leary's long-term sense of belonging; it is temporary and can change as memes evolve and as individuals engage with different memes.

Therefore, the expectation is that individuals who actively engage in meme usage on social media will have a higher sense of belonging, meaning that those who score higher on a sense of belonging in the survey will also exhibit a stronger level of meme engagement.

3.3.Participants

Table 1: Cross-tabulation of gender and age of participants

X\Y |

Below 18 |

18-30 years old |

Above 30 years old |

Subtotal |

|

Male |

1(1.28%) |

71(91.03%) |

6(7.69%) |

78 |

|

Female |

2(5.13%) |

30(76.92%) |

7(17.95%) |

39 |

|

Other gender |

2(28.57%) |

5(71.43%) |

0(0.00%) |

7 |

There was a total of 124 participants who completed the online survey via the questionnaire QR code. Among the sample, 78 individuals identified as male, constituting 62.9% of the total sample; 39 individuals identified as female, making up 31.45% of the total sample; and 7 individuals identified as other genders, accounting for 5.65% of the total sample.

Out of the 124 participants who took the survey, 85.48% were aged between 18 and 30, 10.48% were aged 30 or older, and only 4.03% were under the age of 18. This indicates that the primary audience for the survey falls within the age range of 18 to 30.

According to the data table, 79.03% of participants reported having encountered memes or similar recurring content, while only 20.97% of participants had not encountered such content. Those who had not encountered such content will not be included in the subsequent data analysis.

4.Results

4.1.The group of individuals who have encountered memes

Table 2: Statistical table of participants' exposure to meme by age group

X\Y |

Yes |

No |

Subtotal |

Under 18 years old |

2(40%) |

3(60%) |

5 |

18~30 years old |

94(88.68%) |

12(11.32%) |

106 |

Above 30 years old |

2(15.38%) |

11(84.62%) |

13 |

From the obtained data, it is evident that 98 individuals, constituting 79.03% of the participants, have encountered memes or similar recurring content, while 26 individuals, making up 20.97% of the participants, have not encountered such content. Those who have not encountered memes or similar content will not participate in the subsequent analysis. Clearly, the use of memes or similar recurring content on social media is quite common.

4.2.The level of involvement or engagement with memes

Participants vary in the frequency of their exposure to memes on social media. Among them, 32.65% are frequent users, 24.49% encounter memes occasionally, 32.65% do so regularly, and 34.69% encounter memes almost every time they use social media. Only 6.12% of participants have rarely encountered memes. Among those who have encountered memes, the frequency of exposure to memes on social media is generally high.

Within the group of participants who have encountered memes, those who engage with memes by liking, commenting, or sharing almost every time they use social media make up the highest percentage at 19.39%, followed by regular engagers at 22.45%. Those who engage with memes occasionally by liking, commenting, or sharing represent 35.71% of the group, while those who engage very infrequently or rarely make up 10.2% and 12.24% respectively.

In summary, over half of the participants (57.45%) frequently or almost always engage with memes when using social media, indicating a high level of interaction with meme-related content.

Participants who rarely or very infrequently engage in the dissemination and creation of memes account for 33.67%, those who occasionally engage make up 32.65%, and those who engage regularly or every time they use social media for meme creation represent another 33.67%. The distribution of participants with different levels of engagement appears relatively balanced based on the data.

4.3.Measurement of a Sense of Belonging in Using Social Media

The questionnaire for measuring the sense of belonging utilizes the belongingness scale provided in the appendix of the article "Construct Validity of the Need to Belong Scale: Mapping the Nomological Network." Respondents indicate the degree to which each statement is true or characteristic of them on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all, 2 = slightly, 3 = moderately, 4 = very, 5 = extremely). Some of the items are reverse-scored. Higher scores indicate a higher level of belongingness, while lower scores indicate a lower level of belongingness.

Once the questionnaires are collected, the sense of belonging scores for each participant will be computed for further investigation into the "relationship between meme usage and a sense of belonging."

4.4.The Association between Meme Usage and a Sense of Belonging on Social Media

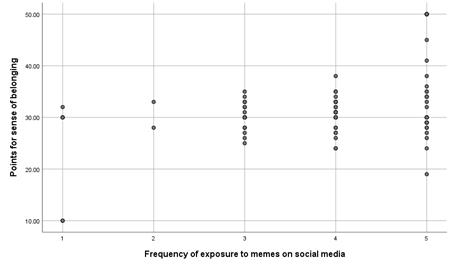

Figure 1: Scatterplot of belongingness scores for participants with different frequencies of exposure to the meme

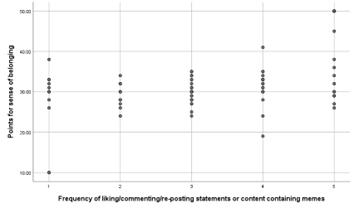

Figure 2: Scatterplot of belongingness scores for participants with different frequencies of liking/commenting/ re-posting statements or content containing meme

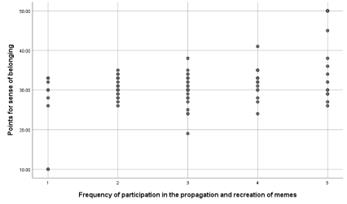

Figure 3: Scatterplot of belongingness scores for participants with different frequencies of participation in the propagation and recreation of meme

The three charts above depict the relationship between different levels of meme engagement and scores of a sense of belonging, presented as scatter plots. The X-axis represents the three levels of meme engagement, while the Y-axis represents the scores of a sense of belonging. Meme engagement is categorized into five levels (1 = Hardly ever, 2 = Rarely, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = Often, 5 = Almost every time I use social media).

Higher scores on the sense of belonging indicate that participants have a stronger sense of belonging, and conversely.

5.Discussion

5.1.Usage of Memes on Social Media

Based on the data obtained from the survey, the usage of memes has become very common. Memes have become a prevalent form of expression on social media, with the primary users being the younger demographic between the ages of 18 and 30. This trend may be associated with their coming of age during the internet era. However, even among those aged 30 and above, there is still a portion of the population that has encountered memes, although the proportion is relatively smaller compared to the younger age group.

Table 3: Statistical table of respondents with different frequency of exposure to meme

Options |

Subtotal |

Ratio |

Almost never |

6 |

6.12% |

Rarely |

2 |

2.04% |

Sometimes |

24 |

24.49% |

Often |

32 |

32.65% |

Almost every time I use social media |

34 |

34.69% |

The number of valid entries for this question |

98 |

Among the surveyed 98 individuals, there were only 8 people (8.16%) who had very limited exposure to memes, 24 people (24.49%) encountered memes occasionally, and 66 people (67.34%) had a higher level of exposure to memes. For the majority of individuals who had encountered memes, their frequency of exposure to memes was relatively high. Memes have become a phenomenon in the Chinese internet and have evolved into a distinct form of social interaction.

5.2.Discussion on the Association between Memes and a Sense of Belonging on Social Media

The discussion related to the three scatterplots depicting the association between a sense of belonging and various aspects of meme engagement on social media can be summarized as follows:

The three scatterplots correspond to questions about the correlation between a sense of belonging score and the frequency of exposure to memes on social media, the frequency of liking/commenting/re-posting statements or content containing memes, and the frequency of participation in the propagation and recreation of memes. It is evident that the level of engagement with meme usage varies from weak to strong in the three plots.

In Scatterplot 1, the sense of belonging scores is distributed on both sides of the mid-point score of 30, and the higher the frequency of exposure to memes, the more dispersed the distribution of a sense of belonging. Within the group exposed to memes, the sense of belonging scores is widely dispersed, with the highest score being 50 and the lowest score, apart from the minimum of 10.

In Scatterplots 2 and 3, there is an overall trend where sense of belonging scores become more concentrated and then disperse as the frequency of meme usage increases. The highest concentration of sense of belonging scores is observed at the "rarely" and "sometimes" frequency levels.

Comparing the three scatterplots, it is noticeable that individuals who participate in meme usage and propagation every time they use social media, representing the highest level of engagement, have denser scatter distributions in all three plots. However, the overall trend indicates that these highly engaged individuals experience an overall increase in their sense of belonging while using social media.

In the first scatterplot, the x-axis represents "Frequency of exposure to memes on social media," where exposure to memes reflects lower engagement levels, while liking, commenting, and using memes for propagation represent relatively higher engagement levels. Therefore, there is a certain correlation between high-frequency engagement in meme usage on social media and a higher sense of belonging while using social media.

5.3.Discussion of the Results

In the Chinese internet landscape, memes are used for expressing one's thoughts and creating humor. When using memes, those who do not understand the meaning of a particular meme may not grasp the intended message, while those who are familiar with the meme's meaning can relate to it. In such a process of dissemination, there can be an information barrier between groups that use different memes. On the other hand, groups that use the same meme may develop a sense of belonging.

Based on the data collected through the questionnaire and by comparing the distribution patterns in the scatterplots, it can be suggested that individuals who use memes with high frequency and high engagement levels tend to exhibit a higher sense of belonging on Chinese social media platforms.

5.4.Limitations and Recommendations

The survey findings summarized in this paper suggest a trend of higher sense of belonging on social media among individuals who use memes with high frequency and high engagement levels. However, how this unique sense of belonging to a particular group is generated within the context of meme dissemination and recreation remains unknown. This could potentially be a future research direction within the same theme.

In the relationship between meme usage and a sense of belonging on social media, age and gender might be significant influencing factors that could impact this association. Further systematic data analysis may be needed to explore these aspects.

Since the survey questionnaire was distributed through WeChat group chats and WeChat Moments, despite using multiple distribution sources, there may be a high degree of social homophily among the participants in these distribution networks. Additionally, participants were primarily concentrated in the eastern coastal regions of China, and other factors such as economic conditions might influence the results. Therefore, future research could consider employing more robust research methods to obtain more accurate data for analysis.

6.Conclusion

Based on the data obtained from the questionnaire, the following conclusions can be drawn. The usage of memes has become widespread on the Chinese internet, especially among younger age groups. Memes, as a semantic construct, possess a natural exclusivity to those unfamiliar with their meanings. In the process of using memes, individuals tend to experience a higher sense of belonging, with this sense of belonging showing an increasing trend as meme usage frequency and engagement levels increase.

References

[1]. The selfish gene[M]. Oxford university press, 2016.

[2]. Nooney L, Portwood-Stacer L. One does not simply: An introduction to the special issue on Internet memes[J]. Journal of Visual Culture, 2014, 13(3): 248-252.

[3]. Mina A X. Batman, pandaman and the blind man: A case study in social change memes and Internet censorship in China[J]. Journal of Visual Culture, 2014, 13(3): 359-375.

[4]. Shifman L. Memes in a digital world: Reconciling with a conceptual troublemaker[J]. Journal of computer-mediated communication, 2013, 18(3): 362-377.

[5]. Baumeister R F, Leary M R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation[J]. Interpersonal development, 2017: 57-89.

[6]. Clark L A, Watson D. Mood and the mundane: relations between daily life events and self-reported mood[J]. Journal of personality and social psychology, 1988, 54(2): 296.

[7]. Linville P W, Jones E E. Polarized appraisals of out-group members[J]. Journal of personality and social psychology, 1980, 38(5): 689.

[8]. Hagerty, B. M., & Patusky, K. (1995). Developing a measure of sense of belonging. Nursing Research, 44, 9–13

[9]. Lee R M, Robbins S B. Measuring belongingness: The social connectedness and the social assurance scales[J]. Journal of counseling psychology, 1995, 42(2): 232.

[10]. Malone G P, Pillow D R, Osman A. The general belongingness scale (GBS): Assessing achieved belongingness[J]. Personality and individual differences, 2012, 52(3): 311-316.

[11]. Leary M R, Kelly K M, Cottrell C A, et al. Construct validity of the need to belong scale: Mapping the nomological network[J]. Journal of personality assessment, 2013, 95(6): 610-624.

Cite this article

Chen,K. (2024). The Relationship Between the Usage of Memes on Social Media in the Chinese Internet and a Sense of Belonging. Communications in Humanities Research,30,90-98.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. The selfish gene[M]. Oxford university press, 2016.

[2]. Nooney L, Portwood-Stacer L. One does not simply: An introduction to the special issue on Internet memes[J]. Journal of Visual Culture, 2014, 13(3): 248-252.

[3]. Mina A X. Batman, pandaman and the blind man: A case study in social change memes and Internet censorship in China[J]. Journal of Visual Culture, 2014, 13(3): 359-375.

[4]. Shifman L. Memes in a digital world: Reconciling with a conceptual troublemaker[J]. Journal of computer-mediated communication, 2013, 18(3): 362-377.

[5]. Baumeister R F, Leary M R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation[J]. Interpersonal development, 2017: 57-89.

[6]. Clark L A, Watson D. Mood and the mundane: relations between daily life events and self-reported mood[J]. Journal of personality and social psychology, 1988, 54(2): 296.

[7]. Linville P W, Jones E E. Polarized appraisals of out-group members[J]. Journal of personality and social psychology, 1980, 38(5): 689.

[8]. Hagerty, B. M., & Patusky, K. (1995). Developing a measure of sense of belonging. Nursing Research, 44, 9–13

[9]. Lee R M, Robbins S B. Measuring belongingness: The social connectedness and the social assurance scales[J]. Journal of counseling psychology, 1995, 42(2): 232.

[10]. Malone G P, Pillow D R, Osman A. The general belongingness scale (GBS): Assessing achieved belongingness[J]. Personality and individual differences, 2012, 52(3): 311-316.

[11]. Leary M R, Kelly K M, Cottrell C A, et al. Construct validity of the need to belong scale: Mapping the nomological network[J]. Journal of personality assessment, 2013, 95(6): 610-624.