1. Introduction

The 19th Century it was emerged as an era marked by tumultuous upheavals. With Napoleon's rise and the French Revolution, Europe was plunged into chaos. With its origins in the United Kingdom, industrialization spread across Europe, resulting in a profound transformation in production. This transformation catalyzed urbanization and technological innovation, restructuring labor and societal relationships. Concurrently, international trade experienced an exponential surge, expanding the global trade network and accelerating the flow of commodities and information.

Politics saw the unification of German-speaking states, while Russia expanded into Siberia and Central Asia, enforcing serfdom reforms simultaneously. Upon the end of the Edo period and the advent of the Meiji Restoration, Japan underwent a fantastic transformation and developed into a highly developed modern Asian nation.

In China, the repercussions of the Opium Wars (1839-1842) and the imposition of unequal treaties triggered a period of turmoil and fragmentation. A wave of Western ideas and scholarship entered China significantly during the Qing Dynasty, which initially adhered to an isolationist policy.

Under these circumstances, the numerous Eastern cultures originating in Asia profoundly influenced the development of European Art. However, Europe needed a clear and well-defined differentiation between the various Eastern cultures and nations. Due to Japan's emergence as a modern nation after the Meiji Restoration, characterized by an advanced level of development and more significant influence than other Asian countries, many European scholars attributed to Japan the origin of forms of ambiguous cultures.

During the Meiji Restoration (1868–1912), which saw the establishment of a modern political system and increased international commerce, Japan saw a transition from a closed, feudal society to one that was quickly industrializing and modernizing. Japan began to assimilate Western culture while insisting on developing its cultural traditions after the Japanese imperial family issued their founding document, Charter Oath of Five Articles (Gokajō no Goseimon in Japanese), announcing the country's goal of modernization and internationalization and stressing the importance of respecting traditional values.

The most important feature of the Meiji period was Japan's struggle to recognize its considerable achievement and equality with Western nations. Japan successfully organized an industrial, capitalist state on Western models [1]. Despite the tenuous existence of a connection between China and Europe, relatively few people are aware of it. China has been carving out impacts on Japan since the Tang dynasty.

Japan sent missions to Tang China throughout the seventh and ninth centuries to conduct negotiations and gain information about the country's more sophisticated governmental structures and culture, including law, Chinese Buddhism, and Chinese Art [2].

In addition, monks of China traveled to Japan, particularly Jianzhen. The customary attire of Japanese ladies is powerfully symbolic of the hair buns and moth-eyed eyebrows of the Tang-era women, and there are still plenty of Tang-inspired buildings in Nara and Kyoto today. Jianzhen, a Tang Dynasty Chinese monk, erected the Buddhist temple Tshdai-ji in Nara in 759. It was built in the Tang architectural style. A Chinese writer named Yan Wenjing, who wrote about a desire for amicable Sino-Japanese relations, noticed that the lotus flowers surrounding Jianzhen's graphic at the Tshdai-ji temple came from China, in addition to the temple's profound links to Chinese culture [3].

The Song Dynasty's diplomatic contacts with Japan were far more extensive and complex than the Tang Dynasty, especially concerning Zen culture. Cultural exchange between Japan and Song was mainly carried out by Japanese monks who traveled between these two nations on merchant ships, unlike the Tang period when Japan sent out formal missions [4].

After spending 1187–1911 in China studying Chinese Chan (later known in Japan as Zen), which gained popularity among Song, Myan Eisai, a Japanese Buddhist monk, brought Zen scriptures and green tea seedlings with him when he reintroduced Zen to Japan in 1911. Chan was well-liked among Song [5].

He began constructing Japan's first temple, Shfuku-ji, in Kyushu as soon as possible. The social changes in Japan in the modern age are primarily attributable to the gradual introduction of Zen Buddhism by Myan Eisai, which was highly revered by both the samurai class and the country's lower classes.

2. Three Approaches to Proving Chinese Art in Impressionism

2.1. Technique: Chinese Movable Type Printing and Ukiyo-e

The Song Dynasty was the peak of Chinese Art and a period of rapid technical growth. Three of China's Four Great Inventions were created during the period known as the Song Dynasty, including the development of moveable type printing by Bi Sheng during the Qingli years of Emperor Renzong of the Northern Song Dynasty (1041-1048).

Before the invention of printing, a scholar had to copy characters one by one if he would like to publish a brand-new book. After years of experimentation, Bi Sheng invented movable type printing based on woodblock printing [6].

Shen Kuo of the same period recorded this in detail [7]:

During the Tang Dynasty, the use of engraved plates for printing books was yet to be widespread. Only during the Five Dynasties period did King Feng Ying begin printing religious texts using this method. Bi Sheng, a commoner in the Qingli period, revolutionized movable type printing. His technique involved crafting characters from collodion, which were then made into character molds and hardened by fire. An iron plate was prepared and coated with turpentine, wax, and paper dust. To print, an iron frame was positioned on the scale, and character molds were arranged within it. Once filled, the structure served as the printing plate, heated near a fire. A flat plate was pressed against it, ensuring flat characters. This method proved highly efficient for large-scale printing. After Bi Sheng's passing, his character molds were treasured by his descendants.

Chinese printing with moveable type expanded eastward to Korea and Japan, then westward to Persia and Egypt, and finally across the world, considerably promoting cross-cultural interactions.

Chinese and Buddhist influences predominated in Japan throughout the 8th and 9th centuries, particularly during the Nara era (710–794). Every aspect of Chinese civilization, including the skill of printing, was introduced [8].

At the end of the 16th Century, Japan used movable type to publish the Ancient Book of Filial Piety and the Book of Exhortation.

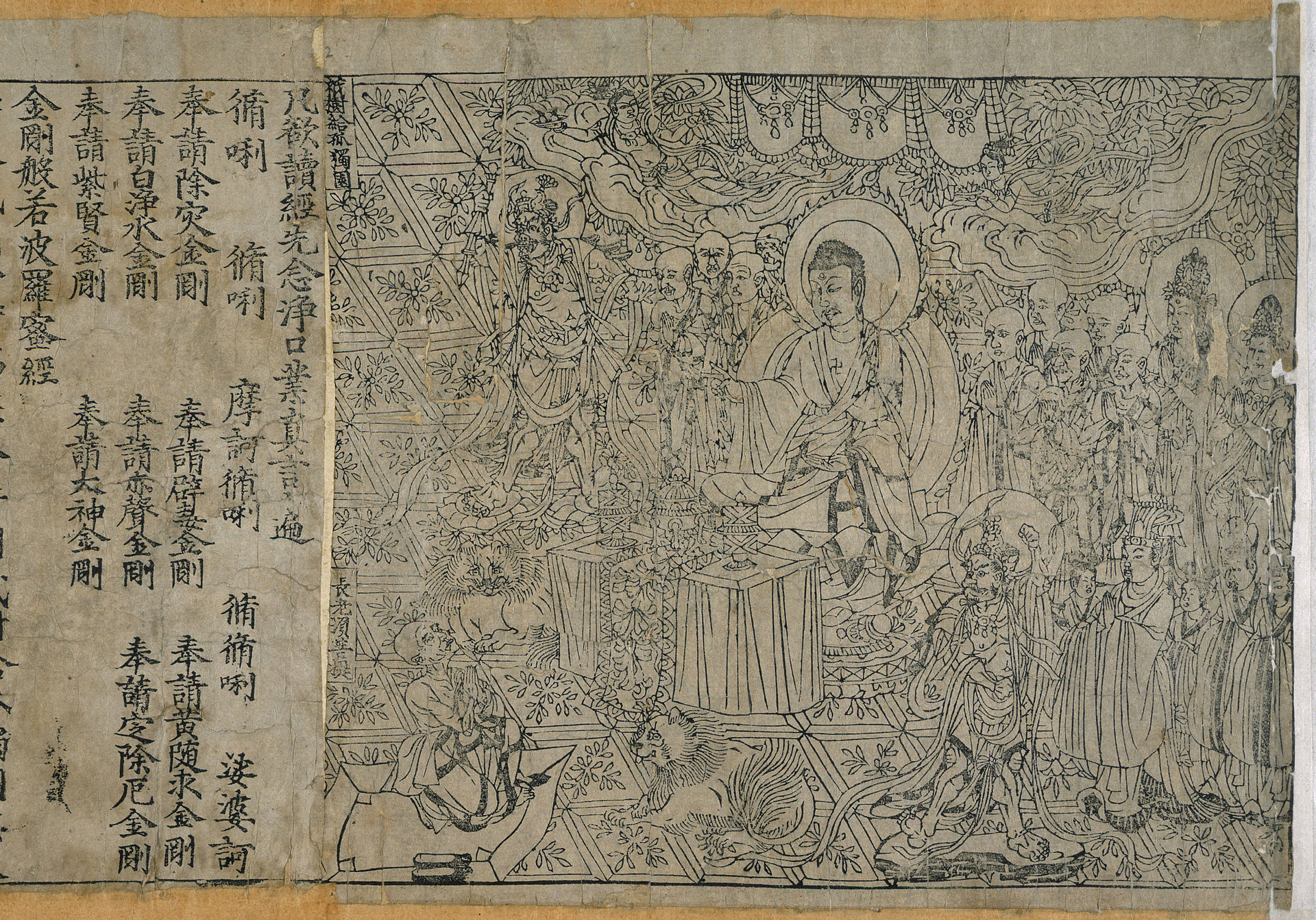

Numerous Impressionist-inspired individuals would initially conjure images of Japanese ukiyo-e when considering printing, but the medium has a more than 1,400-year history in China. The first prints (Figure 1) were created in China to propagate Buddhist culture, mainly for the Vajra Sutra.

Figure 1: Diamond Sutra, 2023 [9]

"Japanese Art since the Heian period (794–1185) had followed two principal paths: the nativist Yamato-e tradition, focusing on Japanese themes, best known by the works of the Tosa school; and Chinese-inspired kara-e in a variety of styles, such as the monochromatic ink wash paintings of Sesshū Tōyō and his disciples. The Kanō school of painting incorporated features of both [10]."

Japan encountered relatively stable governance, quick economic growth, and a gradual but ongoing improvement in printing technology during the Edo period (1603–1868), also known as the Tokugawa period. With the rise of the civic class, ukiyo-e ("pictures of the floating world"), which reflected the aesthetic preferences of the populace, also came into being.

The "father of ukiyo-e," Hishikawa Shishin, established the first independent book drawings in the 1670s with similar themes showing women's daily lives. These works are considered to be the oldest examples of ukiyo-e. Suzuki Shunshin's "Kin-e" popularity in 1760 contributed to the standardization of full-color printing. Due to Suzuki Harunobu's "Nishiki-e" popularity in 1760, full-color printing became the norm.

2.2. Motif: Transfering Chinese Iconography on Ukiyo-e

Japan, an island nation, has developed a vibrant culture due to mainland China's impact. Around the time of the Nara period (710-794), mainland culture's superior designs and skills started to be absorbed entirely. Since then, they have been welcomed in all eras and have developed into a distinct culture [11].

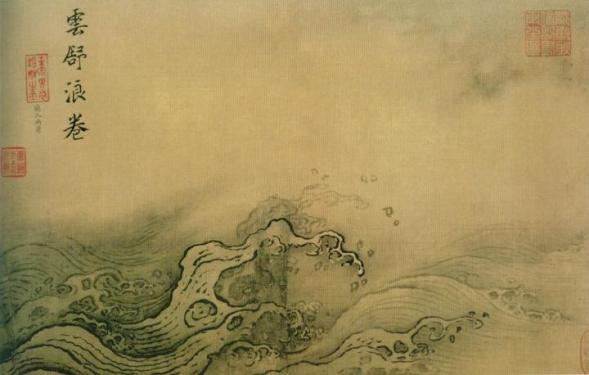

Figure 2: Water Scroll (Shui Tu), Partial Ten Clouds and Waves, Ma Yuan [12]

Ma Yuan was one of the "Four Southern Song Masters" and a painter with a background in the Southern Song. Despite water being an unseen substance, Ma Yuan depicts each of the twelve stages of water in exquisite detail throughout the book's twelve pages. Ma Yuan created one of the few known traditional Chinese paintings (Figure 2) in which water is the topic of representation since water often plays a supporting role in traditional Chinese landscape paintings. The revolving lines that show the rolling waves beneath the clouds and mist, the claw-shaped choppy waves flying into the distance in the Water Scrolls, and the contrasting ink hues provide a sense of instability and unpredictability.

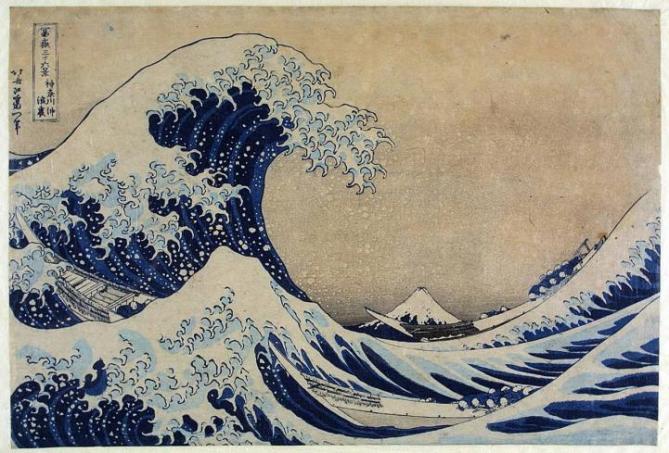

Figure 3: The Great Wave off the Coast of Kanagawa, Katsushika Hokusai [13]

One of the most renowned ukiyo-e masters, Katsushika Hokusai, developed a curiosity about the way that water took on many forms. In several of his paintings, he watched and captured the ocean. His The Great Wave off the Coast of Kanagawa (Figure 3) is full of dramatic, huge waves forming claw-like shapes like Ma Yuan's water scrolls, but more compact and numerous, with greater tension and unease. The vibrant colors of the waves contrast with the relatively monotonous background, heightening the tension and highlighting the momentum of the waves.

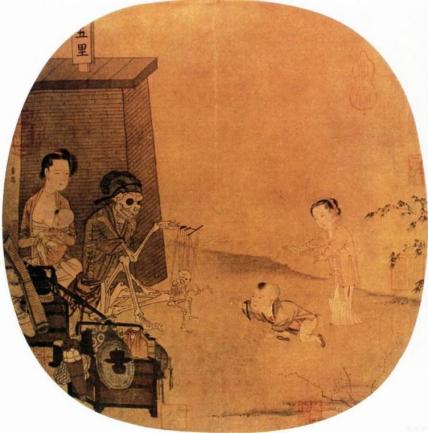

Figure 4: Skull and Skeleton Illusion Play, Li Song [14]

Among the items on show at a recent special exhibition in the Forbidden City is this most enigmatic and odd "ghost painting" of the Song Dynasty. Figure 4 shows that the lady in the image's background is in a panic as a skeleton resembling a salesperson manipulates a tiny frame, a kid is drawn to the structure and reaches out to touch it, and another mother is quietly nursing her child behind the giant skeleton. Several hypotheses exist to explain this strange sight.

The skeleton was a characteristic amusing metaphor for humans throughout the Song and Yuan dynasties. Still, as time passed, its symbolic significance was lost, which is why people now feel outraged by this image. The Taoist notions of "harmony" and "joy in death," as well as the Buddhist concepts of "silence" and "nirvana," are the ideological foundations of the skeleton fantasy theatre. This painting exhibits Li Song's distinctive, lively, and entertaining style while embodying these ideological foundations [15].

Aside from religious works, few paintings throughout Chinese Art dealt with the forbidden subject of death, giving Li Song's Skeleton Phantasmagoria a significant and unique significance.

Notwithstanding the surrealistic appearance of the painting, Li Song was a realistic painter who lived during the Southern Song Dynasty, a time when sorcery was already widely practiced at a high level of ability across many fields. Some have stated that the image shows a nursing mother engaging in witchcraft.

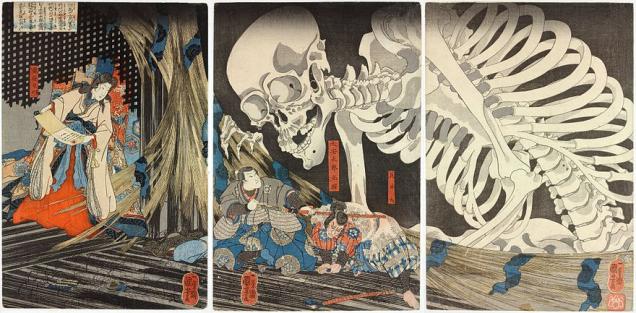

Figure 5: Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre, Utagawa Kuniyoshi [16]

The ukiyo-e woodblock triptych was produced by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798–1861) based on moments in Japanese history. In 939, a rebellion led by the warlord Heisho Mon of the Soma region was put down, and he was subsequently defeated and executed. Princess Taki Yakko, a rebellious Heisho Mon's daughter, is the woman in the photo.

As shown in Figure 5, the scene depicts the Princess employing magic to call forth a massive skeleton by reading an incantation from a hand scroll. It emerges from the shadowy depths and thrusts its fingers through the crumbling palace shutters, posing a threat to Koukoku and his allies, assigned by the Emperor to find the Princess.

2.3. Aesthetic Fusion: Translating Ukiyo-e into Impressionism

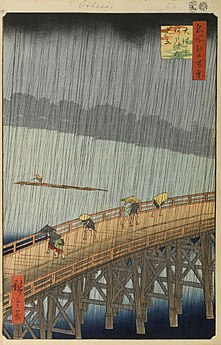

Figure 6: Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake, Hiroshige, 1857 [17]

One of the works from the Japanese artist Hiroshige's (1797–1858) collection of One Hundred Famous Views of Edo is titled Sudden Shower over Shin-hashi Bridge and Atake. The image (Figure 6) depicts boatmen paddling on rafts beneath the new bridge across the river and people hurrying to escape the unexpected downpour while using umbrellas.

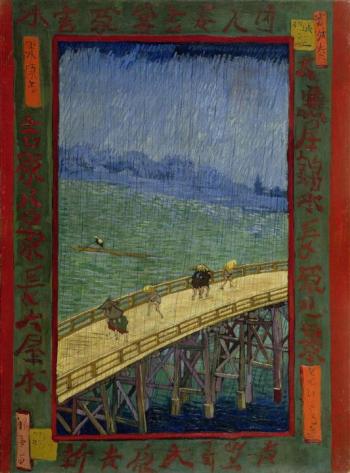

Figure 7: Brug in de regen- naar Hiroshige,Vincent van Gogh [18]

Vincent van Gogh was a major collector of Japanese prints [19].

In addition to using them to decorate his studio, he has also produced replicas. He occasionally uses Japanese prints as the background of his paintings.

In Van Gogh's rendition of the Sudden Shower over the Shin-Hashi Bridge and Atake, as shown in Figure 7, the light-colored river has been changed into a darker green, and the dark-colored river has been transformed into a darker blue. The picture also features more vibrant saturated colors and more pronounced contrasts than the original.

The serene image also has a feeling of movement because of the delicate brushstrokes, even if Van Gogh's copy has less exaggerated fluidity of brushstrokes compared to his previous works and compared to the original's single block of color.

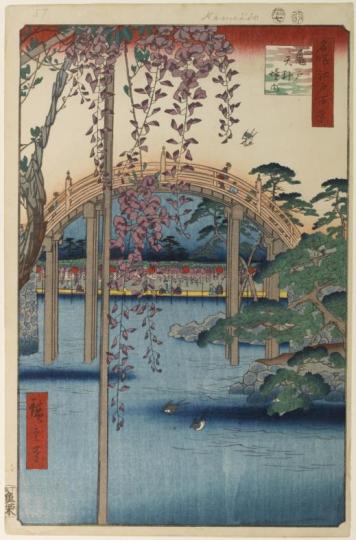

Figure 8: Inside Kameido Tenjin Shrine, One Hundred Famous Views of Edo series, Hiroshige, 1856 [20]

In the 1660s, Kameido Tenjin was built on the Sumida River's eastern bank to ward off evil spirits and safeguard a new township plan. Here, one of the two bridges inside the precincts that indicate the shrine's approach serves as a hint. Figure 8 was one of two bridges in Edo known for possessing a "drum" form. The bridge's wisteria blooms, for which the temple was famous, prove that it is Kameido Tenjin. One of the most frequented annual destinations for Edokko, or Edoites, was the bridge during the wisteria season [21].

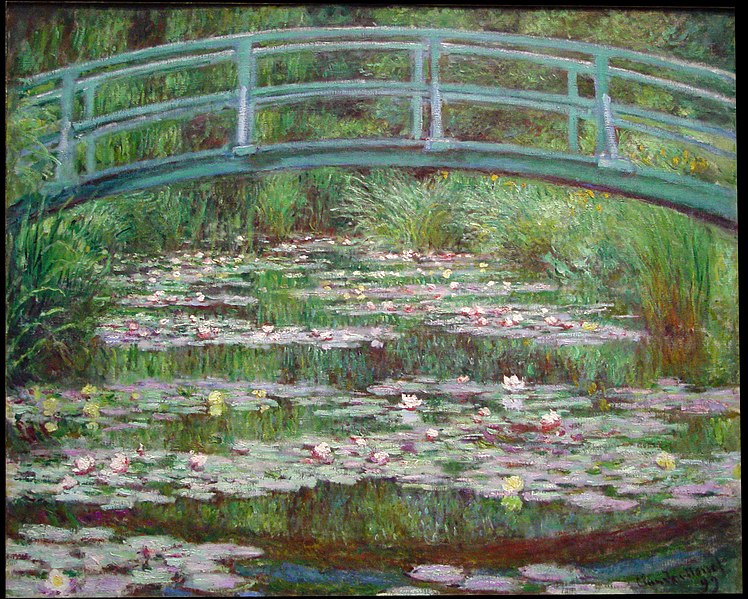

Figure 9: The Japanese Footbridge, Claude Monet, 1899 [22]

Monet admired ukiyo-e and erected a wooden arch bridge as a Japanese bridge in his garden, as shown in Figure 9. He also collected much ukiyo-e at his house in Giverny. Because of his upbringing in the harbor city of Le Havre in France's Normandy, France Monet developed a fascination with water. He ultimately settled in a hamlet on the Seine River, where he constructed a pond filled with lotus blossoms, which was his works' primary inspiration.

Deeply admiring Nature's central role in Japanese culture, Monet fuses Japanese motifs with his impressionist palette and brushstrokes to posit a hybrid, transcendent understanding of Nature's priority [23].

3. Comparative Analysis: Claude Monet's Water Lilies series and A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains by Wang Ximeng

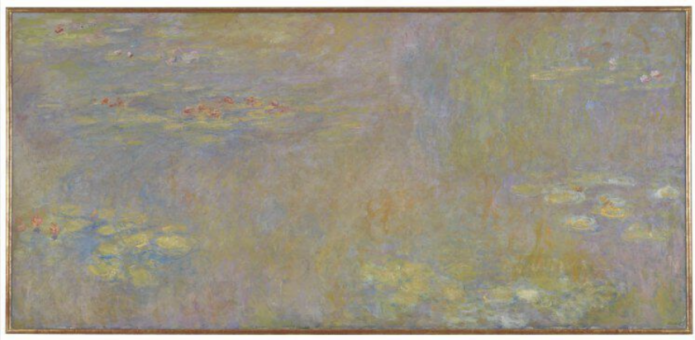

Figure 10: Water-Lilies, Claude Monet [24]

Figure 11: Part (1) of A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains, Song dynasty, Wang Ximeng [25]

Figure 12: Part (2) of A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains, Song dynasty, Wang Ximeng [26]

Initially, Claude Monet's remarkable "Water Lilies" series, comprised of 250 works, had become the artistic focus of the last three decades of his life. With the gradual departure of family and friends and the effects of World War I, Monet's Water Lilies not only evoke a deep desire for serenity, providing solace and eternal significance, but they are also works of patriotic manifestation of French civilization.

Likewise, A Thousand Miles of Rivers and Mountains, a silk landscape painting by Wang Ximeng from China's Northern Song Dynasty, now housed in the Palace Museum in Beijing, is embedded with devotion to the family and country. With its streamlined method, dazzling colors, and brushwork, the lengthy scroll conveys the world's grandeur while expressing the classical elegance of the royal family and the view of the mountains and rivers of China's Northern Song Dynasty. The painting also embodies the harmony between man and nature, depicting a living environment that can be lived in and traveled to, full of longing and yearning for life.

Turning to the National Gallery's display of the "Water Lilies," as shown in Figure 10, there is no sense of distance and perspective in the picture, only blurred tones filling the view, making it impossible to discern the exact subject of the painting. Oil paints are prized for their capacity to blend colors, achieve subtle shades, and capture intricate light and shadow nuances, offering a versatile medium for artistic expression. The use of oil paints in a wide range of spectrums, including grass green, goose yellow, light purple, and sky blue, adds to the vibrancy and playfulness of the picture.

Conversely, A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains (Figure 11 and Figure 12) witness the mineral pigments' lasting beauty with a clear outline of the mountains. Ground with gem-like minerals, the lime green color does not fall off for thousands of years, and over time, the silk darkens. Still, the color remains vibrant due to its raw materials: blue copper ore, lapis lazuli, and malachite. While the colors are bright and layered, they are also full of the unique texture of mineral pigments. The artist has made the landscapes in the paintings come from reality but are full of fantastical and mysterious colors.

4. Conclusion

It is a limited methodological approach to consider Western and Chinese art history as two different and independent domains of study. Indeed, it is typical for people to unintentionally ignore the subtle and complex effects of cross-cultural impact in a time of unprecedented information overload and rapid technological progress. China has exerted a significant influence on the development of European art history, as evidenced by the established influence relationships between China and Japan as well as the reciprocal impact of Japan on Europe. Such rational thinking has allowed me to reveal a frequently overlooked historical story. Numerous unknown aspects of history's annals await to be told and linked, showing observable underlying themes.

The forecast is essential to recognize that history has a natural ability for objectivity and was once contemporary. Nevertheless, innate interests and preferences always impact one’s capacity for judgment. The future reconstruction of art history depends on how one can view and approach this discipline in light of the scrutiny currently being placed on various academic disciplines, including historiography, and an increased emphasis on venerable traditions and intellectual authorities.

References

[1]. The Meiji Restoration and Modernization. (2023, 9 2). Retrieved from Asia for Educators: http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/special/japan_1750_meiji.htm

[2]. Hoffman, M. (2006, 2 3). Cultures Combined in the Mists of Time: Origins of the China-Japan relationship. Asia Pacific Journal.

[3]. Putonghua Shuiping Ceshi Gangyao (in Japanese). (2004). Beijing.

[4]. History of the Song Dynasty, Biography 250th. (n.d.).

[5]. Jr., R. E., & S. Lopez Jr, D. (2014). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism.

[6]. Xu Renyu. (2015, 8 5). Reasons why printing has not been widely used https://web.archive.org/web/20151222115041/http://www.yzmuseum.com/whsb/view.asp?id=599

[7]. Shen Kuo (n.d.).Volume 18 Techniques in Meng Xi Bi Tan(n.d.).

[8]. Sarton, G. (1926, May). Review of The Invention of Printing in China and Its Spread Westwards by Thomas Francis Carter. Isis, p. 365.

[9]. Figure 1:Diamond Sutra. (2023, October 31). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diamond_Sutra. Frontispiece, Diamond Sutra from Cave 17, Dunhuang, ink on paper. A page from the Diamond Sutra, printed in the 9th year of Xiantong Era of the Tang dynasty, i.e. 868 CE. Currently located in the British Library, London. This sutra was discovered at the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, but probably printed in Sichuan (see "Printed dated copy of the Diamond Sutra"). According to the British Library, it is “the earliest complete survival of a dated printed book”

[10]. Lane, R. (1962, August). Masters of the Japanese Print: Their World and Their Work. The Journal of Asian Studies, p. 488.

[11]. Exhibition Outlines No.7 The Art of Japan and China -Masterpieces up to the 16th Century- (1995/3/25 - 1995/6/18). (2023, 9 3). Retrieved from The Imperial Household Agency: https://www.kunaicho.go.jp/e-culture/sannomaru/zuroku-07.html

[12]. Figure 2:Ma, Y. (n.d.-b). Water Scroll(Shui Tu)Partial Ten Clouds and Waves . About 1212.Now in the Palace Museum, Beijing.Ma Yuan Shui Tu Juan. Retrieved November 3, 2023, from https://m-minghuaji.dpm.org.cn/paint/detail?id=df3320e6acc646118a50505d5562a132.

[13]. Figure 3:Katsushika Hokusai: The Great Wave off Kanagawa. (2022, July 17). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Tsunami_by_hokusai_19th_century.jpg woodblock print, about 1831

[14]. Figure 4:Li, S. (1166—1243). Skull and Skeleton Illusion Play. Retrieved November 3, 2023, from https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E9%AA%B7%E9%AB%85%E5%B9%BB%E6%88%8F%E5%9B%BE/2630643. (1166—1243), color on silk, 27 cm long by 26.3 cm wide

[15]. Lu Dunji (2015, 12). Studies on the History and Culture of Zhejiang, Volume 6. On the Mechanism of Meaning Generation of Li Song's Skeleton Illusionary Play. China: Zhejiang University Press.

[16]. Figure 5:Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre.Jpg. In Wikipedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Takiyasha_the_Witch_and_the_Skeleton_Spectre.jpg woodblock print, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, c. 1844, Japan. Museum

[17]. Figure 6: Sudden Shower Over Shin-Ohashi Bridge and Atake (Ohashi Atake no Yudachi). In Wikipedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hiroshige_Atake_sous_une_averse_soudaine.jpg, woodcut print,ukiyo-e, 1857,Sheet: 14 3/16 x 9 1/8 in. (36.1 x 23.1 cm) Image: 13 1/4 x 8 3/4 in. (33.7 x 22.2 cm)

[18]. Figure 7: Vincent van Gogh - Brug in de regen- naar Hiroshige - Google Art Project.Jpg. In Wikipedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vincent_van_Gogh_-_Brug_in_de_regen-_naar_Hiroshige_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg painting, 1887,oil on canvas,height: 73 cm (28.7 in); width: 54 cm (21.2 in)

[19]. Sonya. (2013, 1 8). Van Gogh and Japanese Art, Part 1 The Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige) & Flowering Plum Tree (after Hiroshige). Retrieved from The Van Gogh Gallery: https://blog.vangoghgallery.com/index.php/en/2013/01/08/van-gogh-and-japanese-art-part-1/

[20]. Figure 8:Utagawa Hiroshige: Inside Kameido Tenjin Shrine (Kameido Tenjin Keidai). In Wikipedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:100_views_edo_057.jpg 1856,Part of the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, no. 065 , part 2: Summer.

[21]. In the Kameido Tenjin Shrine Compound, from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo Artist: Utagawa Hiroshige (Japanese, 1797–1858). (2023). Retrieved from Yale University Art Gallery: https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/49019

[22]. Figure 9:File:Japanese Footbridge-Claude Monet.Jpg. In Wikipedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Japanese_Footbridge-Claude_Monet.jpg,oil on canvas,height: 81.3 cm (32 in) ; width: 101.6 cm (40 in)

[23]. The Japanese Footbridge Claude Monet. (2023). Retrieved from National Gallery of Art: https://www.nga.gov/collection/highlights/monet-the-japanese-footbridge.html

[24]. Figure 10:National Gallery. Claude Monet: Water Lilies. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/claude-monet-water-lilies

[25]. Figure 11:File:Wang Ximeng. A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains. (Complete, 51,3x1191,5 cm). 1113. Palace museum, Beijing.Jpg. (2013, October 8). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Wang_Ximeng._A_Thousand_Li_of_Rivers_and_Mountains._(Complete,_51,3x1191,5_cm)._1113._Palace_museum,_Beijing.jpgcolor on silk, hand scroll,Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing

[26]. Figure 12:File:Wang Ximeng. A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains. (Complete, 51,3x1191,5 cm). 1113. Palace museum, Beijing.Jpg. (2013, October 8). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Wang_Ximeng._A_Thousand_Li_of_Rivers_and_Mountains._(Complete,_51,3x1191,5_cm)._1113._Palace_museum,_Beijing.jpgcolor on silk, hand scroll,Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing

Cite this article

Yin,H. (2024). Unveiling Cross-Cultural Hidden Nexus: An Analysis of China’s Contribution to the Cultural Influence of the East on the West. Communications in Humanities Research,31,105-114.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. The Meiji Restoration and Modernization. (2023, 9 2). Retrieved from Asia for Educators: http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/special/japan_1750_meiji.htm

[2]. Hoffman, M. (2006, 2 3). Cultures Combined in the Mists of Time: Origins of the China-Japan relationship. Asia Pacific Journal.

[3]. Putonghua Shuiping Ceshi Gangyao (in Japanese). (2004). Beijing.

[4]. History of the Song Dynasty, Biography 250th. (n.d.).

[5]. Jr., R. E., & S. Lopez Jr, D. (2014). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism.

[6]. Xu Renyu. (2015, 8 5). Reasons why printing has not been widely used https://web.archive.org/web/20151222115041/http://www.yzmuseum.com/whsb/view.asp?id=599

[7]. Shen Kuo (n.d.).Volume 18 Techniques in Meng Xi Bi Tan(n.d.).

[8]. Sarton, G. (1926, May). Review of The Invention of Printing in China and Its Spread Westwards by Thomas Francis Carter. Isis, p. 365.

[9]. Figure 1:Diamond Sutra. (2023, October 31). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diamond_Sutra. Frontispiece, Diamond Sutra from Cave 17, Dunhuang, ink on paper. A page from the Diamond Sutra, printed in the 9th year of Xiantong Era of the Tang dynasty, i.e. 868 CE. Currently located in the British Library, London. This sutra was discovered at the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, but probably printed in Sichuan (see "Printed dated copy of the Diamond Sutra"). According to the British Library, it is “the earliest complete survival of a dated printed book”

[10]. Lane, R. (1962, August). Masters of the Japanese Print: Their World and Their Work. The Journal of Asian Studies, p. 488.

[11]. Exhibition Outlines No.7 The Art of Japan and China -Masterpieces up to the 16th Century- (1995/3/25 - 1995/6/18). (2023, 9 3). Retrieved from The Imperial Household Agency: https://www.kunaicho.go.jp/e-culture/sannomaru/zuroku-07.html

[12]. Figure 2:Ma, Y. (n.d.-b). Water Scroll(Shui Tu)Partial Ten Clouds and Waves . About 1212.Now in the Palace Museum, Beijing.Ma Yuan Shui Tu Juan. Retrieved November 3, 2023, from https://m-minghuaji.dpm.org.cn/paint/detail?id=df3320e6acc646118a50505d5562a132.

[13]. Figure 3:Katsushika Hokusai: The Great Wave off Kanagawa. (2022, July 17). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Tsunami_by_hokusai_19th_century.jpg woodblock print, about 1831

[14]. Figure 4:Li, S. (1166—1243). Skull and Skeleton Illusion Play. Retrieved November 3, 2023, from https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E9%AA%B7%E9%AB%85%E5%B9%BB%E6%88%8F%E5%9B%BE/2630643. (1166—1243), color on silk, 27 cm long by 26.3 cm wide

[15]. Lu Dunji (2015, 12). Studies on the History and Culture of Zhejiang, Volume 6. On the Mechanism of Meaning Generation of Li Song's Skeleton Illusionary Play. China: Zhejiang University Press.

[16]. Figure 5:Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre.Jpg. In Wikipedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Takiyasha_the_Witch_and_the_Skeleton_Spectre.jpg woodblock print, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, c. 1844, Japan. Museum

[17]. Figure 6: Sudden Shower Over Shin-Ohashi Bridge and Atake (Ohashi Atake no Yudachi). In Wikipedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hiroshige_Atake_sous_une_averse_soudaine.jpg, woodcut print,ukiyo-e, 1857,Sheet: 14 3/16 x 9 1/8 in. (36.1 x 23.1 cm) Image: 13 1/4 x 8 3/4 in. (33.7 x 22.2 cm)

[18]. Figure 7: Vincent van Gogh - Brug in de regen- naar Hiroshige - Google Art Project.Jpg. In Wikipedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vincent_van_Gogh_-_Brug_in_de_regen-_naar_Hiroshige_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg painting, 1887,oil on canvas,height: 73 cm (28.7 in); width: 54 cm (21.2 in)

[19]. Sonya. (2013, 1 8). Van Gogh and Japanese Art, Part 1 The Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige) & Flowering Plum Tree (after Hiroshige). Retrieved from The Van Gogh Gallery: https://blog.vangoghgallery.com/index.php/en/2013/01/08/van-gogh-and-japanese-art-part-1/

[20]. Figure 8:Utagawa Hiroshige: Inside Kameido Tenjin Shrine (Kameido Tenjin Keidai). In Wikipedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:100_views_edo_057.jpg 1856,Part of the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, no. 065 , part 2: Summer.

[21]. In the Kameido Tenjin Shrine Compound, from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo Artist: Utagawa Hiroshige (Japanese, 1797–1858). (2023). Retrieved from Yale University Art Gallery: https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/49019

[22]. Figure 9:File:Japanese Footbridge-Claude Monet.Jpg. In Wikipedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Japanese_Footbridge-Claude_Monet.jpg,oil on canvas,height: 81.3 cm (32 in) ; width: 101.6 cm (40 in)

[23]. The Japanese Footbridge Claude Monet. (2023). Retrieved from National Gallery of Art: https://www.nga.gov/collection/highlights/monet-the-japanese-footbridge.html

[24]. Figure 10:National Gallery. Claude Monet: Water Lilies. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/claude-monet-water-lilies

[25]. Figure 11:File:Wang Ximeng. A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains. (Complete, 51,3x1191,5 cm). 1113. Palace museum, Beijing.Jpg. (2013, October 8). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Wang_Ximeng._A_Thousand_Li_of_Rivers_and_Mountains._(Complete,_51,3x1191,5_cm)._1113._Palace_museum,_Beijing.jpgcolor on silk, hand scroll,Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing

[26]. Figure 12:File:Wang Ximeng. A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains. (Complete, 51,3x1191,5 cm). 1113. Palace museum, Beijing.Jpg. (2013, October 8). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Wang_Ximeng._A_Thousand_Li_of_Rivers_and_Mountains._(Complete,_51,3x1191,5_cm)._1113._Palace_museum,_Beijing.jpgcolor on silk, hand scroll,Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing