1. Introduction

The Sogdians, who lived in the fertile valleys between Amu Darya and Syr Darya in present-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, were a group of people famous for their success in commerce and trade. Due to the scarcity of primary literary documents on the Sogdian traders, it is challenging to depict the whole picture of Sogdian commerce. However, it is certain they played an extremely important role in trade along the Silk Road. Centered in the city of Samarkand, the Sogdian traders not only created long-term, stable trading relationships with China, but also served as middlemen in the trade between many large empires, including China and India. Furthermore, their sphere of influence extended beyond Central and Southeast Asia, and their trading partners included the Persians and Byzantines [1]. In their heyday, which was approximately from the 6th to the 8th century, Sogdian traders dominated commerce along the Hexi Corridor in modern-day Gansu, especially in cities such as Dunhuang and Turpan. They were responsible for the exportation and importation of luxury products in China and therefore controlled the principal trans-Asiatic trade route. Besides silk, the Sogdians traded goods including musk, slaves, precious metals and stones, furs, silverware, amber, relics, paper, spices, brass, curcuma, sal ammoniac, medicinal plants, candy sugar, perfumes, etc. They also established a direct trade of Chinese silk with the Byzantine Empire [2,3]. Indeed, during this period, they controlled almost all aspects of commerce along the Silk Road.

2. Causes for the Success of Sogdian Merchants

There are three main factors that contributed to the unique success of Sogdian merchants in establishing an enduring infrastructure that facilitated commerce along the Silk Road. First, the rapid recovery of Sogdiana from the Great Invasions of eastern nomads allowed Sogdians to rise to dominance in Central Asia over their competitors, such as the Bactrians. Second, the Sogdian colonial expansion after their agricultural and demographic growth allowed Sogdians to expand their sphere of influence in Central Asia and laid the foundations for their future commercial success along the Silk Road. Finally, the existence of a unique merchant class in Sogdian society also contributed to their success as merchants in Central Asia. There are also some minor factors that contributed to their commercial success, such as the use of camels and the organization of trade and settlements. In this part of the paper, not only how archaeological evidence and documentary texts reveal these factors, but also how these factors contributed to the Sogdians’ unique commercial successes along the Silk Road will be discussed.

2.1. The Great Invasion and the Rise of Sogdiana

The Great Invasion was a critical event that led to Sogdian dominance in trade in Central Asia. Based on a variety of Chinese and Byzantine sources, in the second half of the 4th century, there was an influx of Eastern nomadic invaders, namely the White Huns, into Central Asia, disrupting the existing balance of regional power. The Sogdians’ relative stability and rapid recovery during this period, mainly shown in their agricultural and demographic growth, ensured Sogdiana’s success over its neighbors, and ultimately contributed to its rise as a predominant trading center between the 6th and the 8th century until the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana in lower Central Asia.

One great example of a Sogdian trading rival who underwent a rapid decline during this period is the Bactrians, who inhabited the opposite bank of Amu Darya. Their homeland, Bactriana, was severely damaged by invasions and wars between nomadic groups. Archaeological exploration in the region of Balkh, the capital city of Bactriana, seems to entirely confirm that several breaks occurred in the population of the area between the Kushano-Sassanid period and the Muslim conquest, indicating periods of decline caused by nomadic invasion [2]. As Xuanzang, a Chinese Buddhist monk and traveler, suggests, “The country of Baktra (Bactria) is more than eight hundred li (500 meters) from east to west and over four hundred li from south to north, bordered by the Oxus River on the north. Its capital city (Balkh), which is more than twenty li in circuit, is popularly known as Smaller Rājagṛha. It is a strongly fortified city but sparsely populated.” [4]. When compared to Samarkand, which was densely populated, the huge difference in population signals a possible decline of the Bactrian region after the invasions of the nomadic tribes. Furthermore, Bactriana was described as a land of epidemics [2]. The wars between Kidarites, Hephtalites and Sassanids, three nomadic groups that dominated the region, caused further disturbances and turmoil among Bactrians, which made it even more difficult for them to recover from economic and demographic decline until the arrival of the Muslims [2].

On the other hand, Sogdiana seems to be less affected by the invasions and warfare, and the agricultural and demographic growth, probably caused by the sophisticated infrastructures such as canals, led to Sogdiana’s ascendency over rival Bactrian traders. Under the leadership of the Kirates, who both insulated Sogdiana from warfare between nomadic groups and defended them from Sasanian and Hephthalite attacks, Sogdians were less interrupted by warfare compared to their Bactrian neighbors. The construction of the Great Walls was also responsible for protecting Sogdians from foreign attacks. The Great Walls, a colossal work with a circumference of more than two hundred and fifty kilometers surrounding the oasis of Bukhara which dates to around the end of the 5th century, was not the only fortification to be built at that time. In fact, it is possible that the long walls which extended across the north of Sogdiana, from Bukhara to Ferghana, also date from this period [2]. With better protection provided by Kirates leadership, as well as the construction of massive protective walls, the Sogdians were more likely to be less affected by the destruction caused by warfare and invasions, and therefore were better able to recover from the destruction caused by the Great Invasion in the 4th century compared to its Bactrian neighbors.

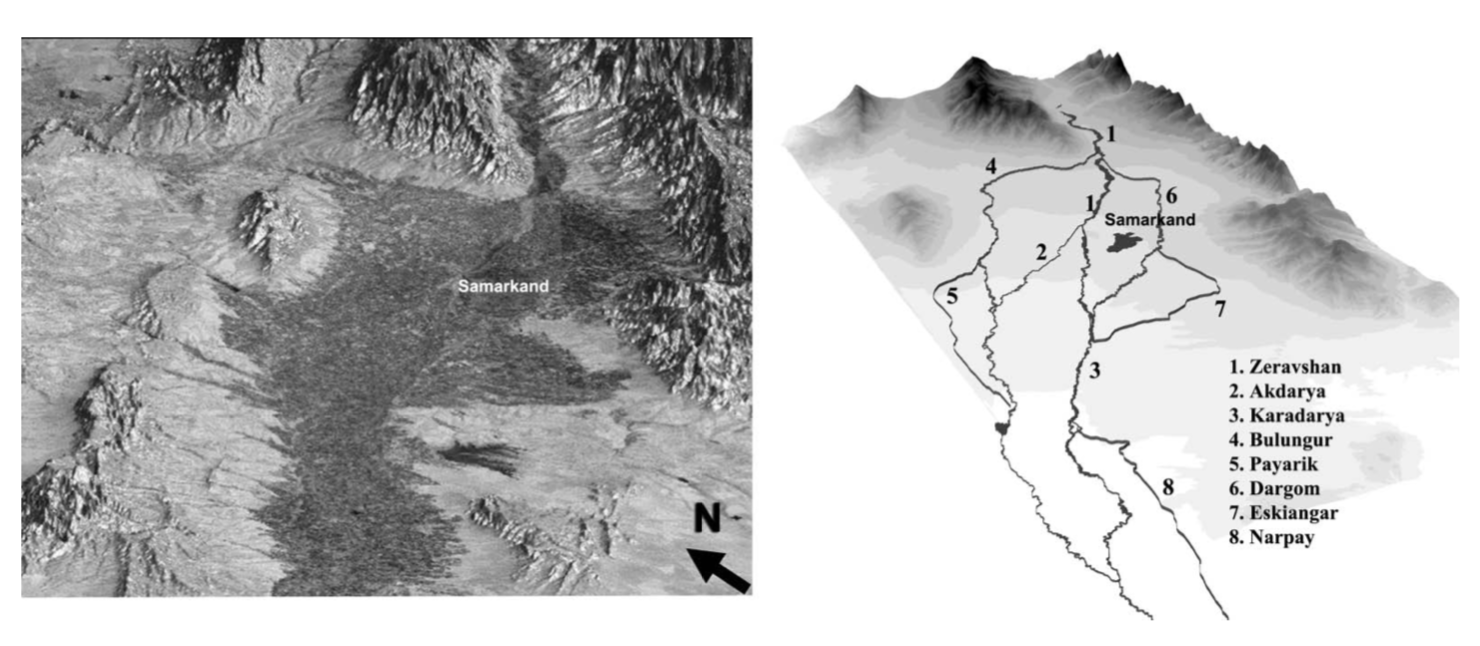

Furthermore, Sogdians had the sophisticated agricultural infrastructure, including a complex system of irrigation and canals shown in figure 1 [5]. that contributed to their agricultural and demographic growth after the invasions and their recovery in the 5th century. One famous example of this type of agricultural infrastructure is the Dargom canal, which is located in modern-day Uzbekistan and was constructed during the foundation of the city of Samarkand. It created a stable supply of water for the residents in Samarkand, laid the foundations for the development of irrigated agriculture, and provided a convenient means of transportation that facilitated trade within the region [6].

Figure 1: Canals around the city of Samarkand

As Sebastian Stride mentions in his study, the agricultural potential of Central Asia depends to a large extent on irrigation. The canals, such as the Dargom Canal, and other complex irrigation systems provided a stable source of water supply that could be used for irrigation, and would therefore increase the agricultural potential in Sogdiana and facilitated agricultural development in the region [5]. Although some of the canals were constructed long before the invasion of the White Huns and would have already had a large impact on Sogdian agriculture long before that period, it cannot be denied that they played an essential role in the agricultural growth during the 5th century in Sogdiana.

Furthermore, according to De la Vaissière, in the oasis of Otrar between modern day China and Kazakhstan, the origins of new methods of irrigation implemented in the 6th century must be sought in the old agricultural civilizations of the south, in Sogdiana [2]. Although the new methods of irrigation were not specified and how these methods could increase the productivity of agriculture remains unknown, it is reasonable to infer that these new techniques also contributed to Sogdian agricultural growth in the 5th century.

In conclusion, after the Great Invasions of the White Huns into Central Asia, most regions, including Sogdiana and Bactriana, were greatly disturbed, and that broke the status quo in this region. While Bactrians, one of the Sogdian trading rivals that lived on the opposite bank of Amu Darya, suffered from pandemics and warfare in Bactriana, Sogdians, on the other hand, experienced both agricultural and demographic growth soon after the invasions, mainly because of their better infrastructure and a high level of isolation from warfare and invasions. The rapid Sogdian recovery in the 5th century helped them gain dominance over trade in Central Asia while groups still suffered from the great damage caused by the invasions; moreover, this also to some extent reflects Sogdian political and social flexibility that would allow them to effectively recover from temporary disturbances from the 6th and the 8th century. Together, this helped ensure their success in building trade relationships along the Silk Road at the expense of their neighbors, and eventually led to their predominant role as Silk Road merchants between the 6th and 8th centuries.

2.2. Sogdian Colonization

Soon after Sogdiana’s recovery from the damage caused by the Great Invasion, combined with the progress of economic dynamism caused by agricultural and demographic growth in the region, Sogdians started to expand their sphere of economic influence through colonization, which laid the foundation for their future success along the Silk Road. Colonization in this paper refers to more of an economic, cultural, or political influence in a region, rather than the modern definition of colonization that usually contains nativist or imperialistic connotations.

According to De la Vaissière, two important regions that were colonized by the Sogdians were Chach and Semirechye in modern-day Uzbekistan and southeastern Kazakhstan respectively. Before 500 C.E., neither region had been within the Sogdian world, but after 500 C.E, a variety of archeological evidence reveals that they were largely colonized by Sogdians, and both locations became entirely incorporated into the Sogdian World [7].

Multiple signs of colonization, including monetary exchange and shared legends and coins, have been discovered by archaeologists in Chach. For instance, after the fifth century, the traditional coin in Chach with the legend “ruler in tiara” suddenly disappeared and was gradually replaced by a Sogdian-style coin with “the bust of a diademed king and a squat altar of fire with a circular Sogdian legend.” The gradual replacement of coins suggests possible Sogdian colonization in the region of Chach in the fifth century. Furthermore, archaeological findings reveal that there was significant monetary exchange between Sogdiana and Chach: a large amount of Chach coins was discovered in Penjikent, a town in Sogdiana, while a large amount of Sogdian coins was also discovered in Chach [2]. The monetary exchange could be understood as a sign of Sogdian economic and commercial dominance in Chach, as well as the existence of a long term and stable trading relationship with the region. Moreover, in the Tashkent Oasis, the region where Chach belonged to, it was discovered that the small coins with Sogdian legends were assigned by local lords that held Sogdian positions [2]. This reveals that Sogdians not only had economic, but also political and cultural dominance over Chach, meaning Chach had virtually become a Sogdian colony.

Similar signs of Sogdian colonization were also discovered in Semirechye, a region north of the Tian Shan in Central Asia that is also historically known as the Land of Seven Rivers. In Suyab, a city in Semirechye, archaeological findings show that the establishment of towns around castles was built on the Sogdian model [2]. As Xuan Zang mentions in his Great Tang Records on the Western Regions (Da Tang Xi Yu Ji),

The region stretching from the city of Sushe River (Suyab) up to the country of Kasanna is called Suli (Sogdiana), and the people are known by the same name. Their language is also known as Suli (Sogdian) [4].

It shows that the Sogdians expanded themselves into new regions during the fifth and the sixth century, and they have unified the people in those new regions, shown by Xuanzang’s observation that they shared the same name and spoke the same language. Although the purpose of building these colonies remained controversial, and some colonies were proved by archaeological findings to be initially used for agricultural purposes, it cannot be denied that the control over these new territories provided Sogdian traders with more commercial benefits; also, the monetary exchange between Sogdiana and its colonies shows that some form of transaction must have taken place between those regions, so it is reasonable to argue that these new colonies would help Sogdians to establish a form of primitive short distance trading network that laid the foundations for their future long distance commercial network along the Silk Road.

After the initial colonization of Chach and Semirechye, Sogdians further expanded their territory by building colonies in Dunhuang and Turfan during the 6th and 8th centuries. For example, in his The Sogdian Colony in Dunhuang in the mid-Eighth century, the Japanese scholar Ikeda On, who based his study on Sogdian manuscripts found in Dunhuang, suggests that Sogdians established a colony east of Dunhuang city in the 7th century, with most of them being merchants [8]. Since most of the Sogdian colonists were merchants, it is reasonable to assume that the purpose of Sogdian colonization was mainly economic. By creating permanent settlements, these traders would be able to establish a stable trade relationship with the city of Dunhuang.

In summary, the Sogdians soon expanded their sphere of influence after their agricultural and demographic growth in the 5th century. They first expanded into Central Asia and colonized Chach and Semirechye; later, they created permanent settlements in Turfan and Dunhuang, which would allow them to establish trade relationships with China. Although the purpose of Sogdian colonization remains controversial, with some scholars arguing that the main purpose was agricultural, it is clear that there was trade between Sogdiana and its colonies based on archeological findings on the exchange of currencies. Therefore, it is reasonable to argue that Sogdian colonization would create a primitive commercial network that connected colonies under Sogdian control, which would contribute to their commercial success along the Silk Road between 6th and 8th centuries.

2.2.1. The Social Structure in Sogdian Communities:

The existence of a distinctive merchant class in Sogdian society also enabled Sogdians to be uniquely successful at establishing an enduring infrastructure that facilitated commerce along the Silk Road. As a variety of primary observations and secondary literature suggests, the emphasis on commerce is one important aspect of both Sogdian society and culture which proves the existence of a unique merchant class in Sogdian society.

The emphasis on commerce and profits as well as the existence of a powerful merchant class in Sogdian society gave contemporary travelers and historians a strong impression of the Sogdian traders. For example, during the Tang Dynasty, Xuanzang, a Chinese pilgrim who traveled through Central Asia, wrote about Sogdiana from his perspective in his Da Tang Xi Yi Ji that “...both (Sogdian) parents and child plan how to get wealth, and the more they get the more they esteem each other . . . The strong bodied cultivate the land, the rest [half] engage in money-getting [business].” Later, with regard to Samarkand, he wrote: “the precious merchandise of many foreign countries is stored up here.” [4]. This observation illustrates that the importance of trade and profits was deeply embedded in Sogdian culture and emphasized among Sogdian families by their parents. Similarly, in the New Book of Tang (Xin Tang Shu), a work of official history covering the Tang Dynasty compiled by the famous historian Ouyang Xiu, suggests that “they (Sogdians) excel at commerce and love profit; as soon as a man reaches the age of twenty, he leaves for the neighboring kingdoms; to every place that one can earn, they have gone.” [9]. This quote not only demonstrates Sogdian traders’ strong desire for profits and building trading relationships with their neighbors, but also provides evidence for the Sogdian habit of expanding into neighboring territories to exert economic influence over those regions. These observations prove that the importance of commerce and profits was heavily emphasized in Sogdian society and the existence of a unique and powerful merchant class in Sogdian society. The emphasis on profits and commerce would in turn encourage members of the merchant class to develop an expertise in commerce and provides another explanation for Sogdian traders’ success in Silk Road commerce.

2.3. Other Minor Factors:

2.3.1. Means of Transportation

It is widely believed horses played an important role in the Sogdian early, who simultaneously possessed characteristics of both sedentary and nomadic peoples. Horses created greater mobility that allowed Sogdians to conduct material exchanges and trades, were widely used in warfare, and sometimes served as a source of food because of their meat and milk. However, there is another animal that held equal importance in Sogdian trade along the Silk Road: the camel.

Figure 2: A mural showing a Sogdian trader and a camel, discovered in Taiyuan, Shanxi

A variety of archaeological evidence shows that Sogdian traders used camels as an effective means of transportation along their trade routes. For example, figure 2 [10], a mural discovered in a tomb located in Jinsheng Village in Taiyuan, Shanxi Province, depicts a Sogdian trader and two camels, and the large load on one of the camels’ back shows the camels were positively used for commercial purposes. Moreover, the six Tang Dynasty graves discovered in 2002 next to the Foye Temple in Dunhuang contain large quantities of bricks showing Sogdian traders and their camels [10]. These artifacts demonstrate the prevailing use of camels in travel by Sogdian traders along the Silk Road.

According to Min Feng, a researcher at Ningxia Normal University, there are several benefits that camels would have provided to traders along their trade routes. Compared to other pack animals such as horses and cows, camels can carry more goods, which would allow Sogdian to earn more profits. Moreover, camels have a wider range of diets, which means that they could eat almost anything around them and have a higher chance of survival under the harsh desert conditions [10]. A camel's hump stores large quantities of fat, which can supply them with energy when there is a shortage of food; their sensitive noses could also help traders to locate water supply in the desert [12]. These favorable traits allowed camels to become a favorable means of transportation for Sogdian traders; thus, with camels, Sogdians could earn more profits and have a better chance of survival due to the camels’ ability to detect underground water in a desert. Therefore, camels also contributed to Sogdian success along the Silk Road from the 6th to the 8th centuries.

2.3.2. Organization

Because of the harsh climate along the Silk Road as well as difficulties with regulating commerce across vast regions, the organization was especially important to traders along the Silk Road in terms of their survival and commercial success. Compared to other nomadic groups who lacked a central power base, Sogdian merchants were organized under caravan leaders called a sartapao, or translated in Chinese, sabao. The existence of such an economic hierarchy is well supported by primary sources. The Sogdian Ancient Letter II reveals a possible political or economic hierarchy that existed among Sogdian merchants. Because of the author’s understanding of the geographical region and his discussion about him giving others “permission” to leave the region, it can be inferred that the author was probably one of the trade leaders in China. Moreover, this leader was writing a report to the “lords” and “sirs” back in Samarkand, suggesting the existence of an even higher authority in the capital city of Sogdiana [13]. Combined with the leader’s comments about the “retribution” taken against people who left the region without permission, it could be argued that Sogdian traders were organized under authority figures who created tight regulations and maintained strict discipline. Compared to other contemporary nomadic groups who often lacked a central leader figure, the orderly organized trading system created by Sogdian traders created a sense of discipline among themselves, which contributed to their commercial success along the Silk Road.

3. Sogdian Merchants’ Success in China

As the dating of the Sogdian Ancient Letters discovered in Dunhuang reveals, there was already a Sogdian presence in China in the early 4th century. During the Tang Dynasty, Sogdian merchants gained remarkable success in China. A variety of archaeological evidence illustrates their presence in China for commercial purposes. For instance, the report Case of Kang Weiyi and Luo Shi's Request in the First Year of Tangchuigong discovered in Astana Graves from the tomb No.29 in 1964 in Turpan, Xinjiang reveals that a merchant group consisted of nineteen Sogdian merchants and twenty-nine heads of cattle, which was considerably large in size, once traveled to Turpan to trade [14].

At the peak of their commercial success on the Eurasian continent between 6th and 8th centuries, Sogdians dominated northwestern Chinese cities such as Turfan and Dunhuang and controlled the trade between Chang’an and Sogdian. They even expanded their settlements into northeastern China, including Yingzhou. According to Rong, a historian, and professor at the Peking University, the silver utensils discovered from a Tang tomb indicate that Sogdian merchants settled as far as Yingzhou, Anhui Province in northeastern China [8].

Because of the existence of mutual benefits, the Chinese government in the Tang Dynasty largely supported the Sogdians, which led to their commercial success in the region. As Tang expanded its territory into Central Asia and conquered regions like Turfan, it became more costly for the Tang government to control these new territories, as well as the regions in the Northeast frontier, such as Manchuria [3]. Although it seems that access to Central Asia would guarantee Tang control over trade in the region, the region’s commerce was already dominated by Central Asian traders, such as the Sogdians, and it is unlikely that Tang would earn large amounts of benefits from commerce in this region. Therefore, the Tang government, which became aware of the usefulness of these foreign traders for lowering the costs of maintaining armies, started to create policies that encouraged foreign traders to settle in those regions, and their economic presence would reduce the need for Tang military presence in those regions [3]. Combined with the fact that Sogdiana (Samarkand and Tashkent regions) was under the nominal suzerainty of China during the seventh century, under the reign of the emperor Gaozong (649–683), China must have become a welcoming place for commerce in many Sogdian traders’ minds, which explains increasing Sogdian settlements in China within this period [15]. Other specific policies also contributed to the Sogdian merchants’ success in China during the Tang Dynasty. For instance, the Tang government authorized Sogdian merchants to pay in Sogdian silver coins at markets [3]. This would facilitate the sale and purchase of goods for Sogdian merchants in Chinese markets, and therefore contribute to Sogdian commercial success in China.

Sogdian traders’ quick assimilation, a phenomenon named by many scholars as “Sinicization,'' into Chinese society and culture also contributed to their commercial success in China under the Tang Dynasty. First, Sogdian traders become sinicized mainly by adopting Chinese names. As the manuscript Tang Shen Long three years (707) Gaochang County Chong Hua Township Registration Sample discovered in Turfan points out, among the 56 Sogdian traders living in the region, 32 of the them chose to adopt Chinese last names, such as An or Kang [14]. As another example, the manuscript Gaochang Neizang Reported Price Accounts discovered in Turfan makes the record of 40 Sogdian traders who adopted Chinese last names including Kang, An, He, Shi, and Cao [14]. The large quantity of sources on Sogdians with Chinese names reveals that adopting Chinese names was indeed a prevalent phenomenon among Sogdian settlements in the Tang Dynasty. Sogdian settlers also assimilated into Chinese society by accepting certain cultural practices. As the Table of Tomb of Kang Runu and his wife Zhu suggests, as early as the late 6th century, Sogdian traders living in Turfan started to adopt a burial style that was largely practiced by Chinese, suggesting a possible Sogdian assimilation into Chinese culture [14]. Also, the tomb inscriptions of Sogdian traders shared many similarities with the Han Chinese style. Intermarriage, an important step to cultural assimilation, also occurred between Sogdian traders and Chinese citizens during the Tang Dynasty, and this phenomenon is supported by a variety of primary documents, such as the Tang Lv · Wei Jin Lv. By assimilating into Chinese culture, it was less likely that Sogdian traders would be excluded in Chinese society; therefore, it was more likely that more effective communication between Sogdian and Chinese traders would take place in local markets, which contributed to Sogdian merchants’ success in China.

Sogdians also expanded their political influence in China by holding political positions, which also contributed to their commercial success in China. The position of sabao, or caravan leaders as discussed previously, started to undergo a transformation during the Tang Dynasty. As Sogdians moved to China and “were absorbed into China’s traditional bureaucratic system,” [1], the role of sabao switched from caravan leaders to local administrators or governors. As Tong Dian, an encyclopedia text that focuses on Tang history, suggests, sabao belongs to the fifth pin of government officials, with pin synonymous to level in Chinese [16]. Other positions that also belong to the fifth pin included Master of Ceremony and General of the Forward Army, and this shows that the fifth pin at the time was a relatively high position. Many Sogdians also were able to expand their administrative careers beyond the position of sabao. As the few discovered steles reveal, some Sogdians became director of agricultural works in some rare cases, or even received the title of “General with the Noble Bearing of a Dragon” under the Chinese government in the Tang Dynasty. Although the exact extent of Sogdian political power was not explicitly mentioned in the Tang manuscripts referenced in this paper, Chinese recognition of the title of sabao would give Sogdians actual political power within the Chinese territory, which would allow Sogdians to maintain their autonomy and ensure fair trading practices within regions inhabited by Sogdian traders.

In summary, Sogdian traders gained remarkable commercial success in the Chinese market, as evidenced mainly by a variety of Tang records on Sogdian merchants and goods, as well as archaeological evidence from Sogdian settlements in China, which include Liangzhou, Luoyang, and Dunhuang. Several factors, including favorable Tang government policies, Sinicization of Sogdian settlers, and expansion of Sogdian political power in China, contributed to the unique commercial success of Sogdian merchants in the Chinese market.

4. Conclusion

A quote from David Christian’s Silk Road or Steppe Roads? The Silk Roads in World History can best summarize the importance of nomadic groups in Asian commerce: "In the very early days, nomads brought copper, tin and turquoise from Iran, gold from the Altai Mountains of Mongolia, lapis lazuli and rubies from Afghanistan, fur from Siberia, cotton from Arabia, India, and their own products such as wool, leather and livestock. In the process, they opened major routes across Asia, including the Silk Road.” [17]. Sogdians, who possessed characteristics of both sedentary and nomadic communities, can be considered as one of the most important contributors to the flourishing commercial network along the Silk Road. They achieved this success mainly because of their quick recovery from the destruction caused by the Great Invasions, colonial expansion, and a social structure that included a predominant merchant class. Other minor factors, such as their use of camels and organization of settlement and trade, and protection against nomadic attacks, also contributed to their success in building a commercial network along the Silk Road. Sogdians also became particularly successful in China during the Tang Dynasty, one of its greatest trading partners, mainly caused by the favorable policies created by the Tang government, the process of Sogdian Sinicization, and the expanding role of Sogdians into Chinese politics. Although the scarcity of primary sources on Sogdian traders restricts historians’ understanding of Sogdian commerce, their historical importance and contribution to the establishment of the Silk Road cannot be underestimated.

References

[1]. Di Cosmo, N., Maas, M. (2018) Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

[2]. de la Vaissière, E. (2005) Sogdian Traders: A History. Leiden, Boston.

[3]. de la Vaissière, E. (2014) Trans-Asian trade, or the Silk Road deconstructed. In: Neal, L., Williamson, J.G. (Eds), The Cambridge History of Capitalism. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 101-124.

[4]. Xuanzang. (1996) The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions. Numata Center for Buddhist Translation & Research, California.

[5]. Stride, S., Rondelli, B., Mantellini, S. (2009) Canals versus Horses: Political Power in the Oasis of Samarkand. World Archaeology, 41,1: 73-87.

[6]. Mantellini, S. (2015). Irrigation Systems in Samarkand. In: Selin, H. (eds) Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer, Dordrecht. pp. 1-14.

[7]. Hansen, V. (2003) New Work on the Sogdians, the Most Important Traders on the Silk Road, A.D. 500-1000. T'oung Pao Second Series, 89: 149-161.

[8]. Xinjiang, R. (2001) New Light on Sogdian Colonies along the Silk Road Recent Archaeological Finds in Northern China. In: Lecture at the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences. Berlin. pp. 147-160.

[9]. Ouyang, X. (1975) New Book of Tang. Zhonghuashuju, Beijing.

[10]. Feng, M. (2014) Sogdian Traders on Tang Dynasty Silk Road. Studies of Western Xia Dynasty, 2: 60-65

[11]. Schafer, E. (1963) The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T’ang Exotics. University of California Press, California.

[12]. Pulleyblank, E.G. (1952) A Sogdian Colony in Inner Mongolia. T'oung Pao Second Series, 41: 317-356.

[13]. Sims-Williams, N. (2004) The Sogdian Ancient Letters II. https://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/texts/sogdlet.html.

[14]. Liu, H., Chen, H. (2005) Commercial Migration: Sogdian Traders in Turfan and Dunhuang. Journal of Dunhuang Studies, 2: 117-125.

[15]. Beaujard, P. (2019) Tang China and the Rise of the Silk Roads. In: The Worlds of the Indian Ocean: A Global History. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. pp. 18-41.

[16]. Du, Y. (2005) Tong Dian. Beijing Press, Beijing.

[17]. Christian, D. (2000) Silk Roads or Steppe Roads? The Silk Roads in World History. Journal of World History, 11: 1-26

Cite this article

Liu,C. (2023). Sogdian Traders Along the Silk Road: Causes for Their Commercial Success. Communications in Humanities Research,4,26-34.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies (ICIHCS 2022), Part 2

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Di Cosmo, N., Maas, M. (2018) Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

[2]. de la Vaissière, E. (2005) Sogdian Traders: A History. Leiden, Boston.

[3]. de la Vaissière, E. (2014) Trans-Asian trade, or the Silk Road deconstructed. In: Neal, L., Williamson, J.G. (Eds), The Cambridge History of Capitalism. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 101-124.

[4]. Xuanzang. (1996) The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions. Numata Center for Buddhist Translation & Research, California.

[5]. Stride, S., Rondelli, B., Mantellini, S. (2009) Canals versus Horses: Political Power in the Oasis of Samarkand. World Archaeology, 41,1: 73-87.

[6]. Mantellini, S. (2015). Irrigation Systems in Samarkand. In: Selin, H. (eds) Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer, Dordrecht. pp. 1-14.

[7]. Hansen, V. (2003) New Work on the Sogdians, the Most Important Traders on the Silk Road, A.D. 500-1000. T'oung Pao Second Series, 89: 149-161.

[8]. Xinjiang, R. (2001) New Light on Sogdian Colonies along the Silk Road Recent Archaeological Finds in Northern China. In: Lecture at the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences. Berlin. pp. 147-160.

[9]. Ouyang, X. (1975) New Book of Tang. Zhonghuashuju, Beijing.

[10]. Feng, M. (2014) Sogdian Traders on Tang Dynasty Silk Road. Studies of Western Xia Dynasty, 2: 60-65

[11]. Schafer, E. (1963) The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T’ang Exotics. University of California Press, California.

[12]. Pulleyblank, E.G. (1952) A Sogdian Colony in Inner Mongolia. T'oung Pao Second Series, 41: 317-356.

[13]. Sims-Williams, N. (2004) The Sogdian Ancient Letters II. https://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/texts/sogdlet.html.

[14]. Liu, H., Chen, H. (2005) Commercial Migration: Sogdian Traders in Turfan and Dunhuang. Journal of Dunhuang Studies, 2: 117-125.

[15]. Beaujard, P. (2019) Tang China and the Rise of the Silk Roads. In: The Worlds of the Indian Ocean: A Global History. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. pp. 18-41.

[16]. Du, Y. (2005) Tong Dian. Beijing Press, Beijing.

[17]. Christian, D. (2000) Silk Roads or Steppe Roads? The Silk Roads in World History. Journal of World History, 11: 1-26