1.Introduction

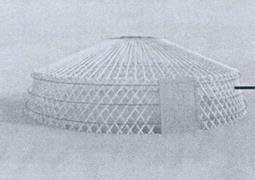

Different regions and ethnic groups have formed their unique architectural cultures under their respective geographical and climatic conditions and lifestyles. To adapt to the unique nomadic lifestyle, the ancestors on the Mongolian Plateau developed a system of grassland tent-like architecture, which is the earliest form of felt tents. With the rise of the Mongol Empire, tent-like architecture with Mongolian ethnicity gradually developed into a system. By the Qing Dynasty, with the successive submission of various Mongolian tribes, the term "yurt" officially appeared, and the indigenous tent system of Mongolia was further improved and developed. It combined with Qing palace culture to form the new Qing palace yurt. In the late modern period, influenced by changes in lifestyle and modernization trends, yurts evolved into a single residential building, with significant changes in structural materials, becoming the standardized "yurt" known to the public today as an important symbol of nomadic life culture. By roughly sorting out the evolutionary process of yurts in different historical periods, we can generally understand how historical and cultural development influenced the form of yurts and eventually formed a typical cultural symbol of nomadic life.

2.Concept Explanation and Definition of Yurt

The Mongolian term for yurt is "ger," which appeared in Mongolian historical materials as early as the 13th century. Sometimes, it is modified with "mongol," meaning Mongolia, becoming "mongol ger." The term "yurt" is a Chinese transcription of the Manchu term, widely spread during the Qing Dynasty, and has ultimately become the typical Mongolian dwelling form known today.

In current literature research and daily usage, the conceptual scope of the term "yurt" is not clearly defined. Sometimes it refers to all tent-like or dome-shaped felt buildings, while at other times, it specifically refers to the standardized yurts with intersecting lattice walls. Overly expanding or narrowing the scope of yurts is not conducive to understanding it as an indigenous architectural type and sorting out its dynamic development. Based on this, the following points are clarified for the concept of yurts in this article:

1.As a typical sample of traditional architecture, the form and style of yurts evolve with time and space, much like traditional wooden structures in ancient China, and are not standardized or fixed. Siegfried Giedion stated that "history is not a static display of facts but a living, evolving pattern of attitudes and interpretations [1]," which is also the premise for discussing yurt architecture from a historical dimension.

2.The yurts referred to here are one type of widely used felt tents on the Eurasian grasslands, having a certain stable Mongolian ethnic character. In addition to Mongolians, Central Asian ethnic groups like Kazakhs and Uzbeks, as well as some nomadic peoples in the Arab region, also use circular felt tents as traditional dwellings. Although these felt tents have certain similarities in their planar structure, they often have distinct regional and tribal characteristics. The kinship between these circular felt tents has not yet been sorted out and clarified. To avoid overly chaotic narration, this article mainly refers to circular felt tents related to Mongolians or closely associated with them.

3.Yurts are not just residential buildings. Just as Gothic architecture includes more than just church buildings, yurts also include public, religious, and official buildings during certain historical periods. For example, the Qing palace yurt was used as a ceremonial building for feasting Mongolian outer vassals and foreign envoys. It is often depicted in the imperial poems and paintings of emperors like Qianlong.

4.Besides yurts, there are many other types of indigenous buildings in Mongolia, including immovable wooden frame structures. The numerous Tibetan Buddhist monastery buildings summarized by Zhang Pengju are excellent examples [2].

3.Climatic Characteristics of the Mongolian Plateau

The Mongolian Plateau mainly experiences a temperate continental climate, with an average annual rainfall of about 200mm. Due to its high latitude, winters on the plateau, from November to April, are cold and long. January, the coldest month of the year, sees average temperatures between -30°C to -15°C, often accompanied by heavy snow and strong winds. Spring and autumn are short, with sudden weather changes. Summer features significant day-night temperature differences, abundant sunlight, and strong ultraviolet radiation, with temperatures reaching up to 35°C [3]. Moreover, the region experiences extreme annual temperature variations.

Overall, the Mongolian Plateau is vast, with diverse topographies such as grasslands, mountains, and deserts, experiencing large annual temperature differences, dryness, and high winds with abundant sand. Yurts adapt to these climatic characteristics, offering excellent windproof and insulation functions. In summer, the felt coverings can be lifted for ventilation.

4.Typical Yurt Structure

As a unique architectural type, the form of yurts has gradually developed a pattern over time, with their components and structures exhibiting a standardized, general, and normative characteristic among regions and tribes. The traditional residential yurt, well-developed in modern times and widely recognized by the public, is used here as an example to introduce the typical structural system of yurts. The traditional residential yurt mainly consists of three parts: the wooden frame system, the felt covering system, and the rope system.

Wooden Frame System:

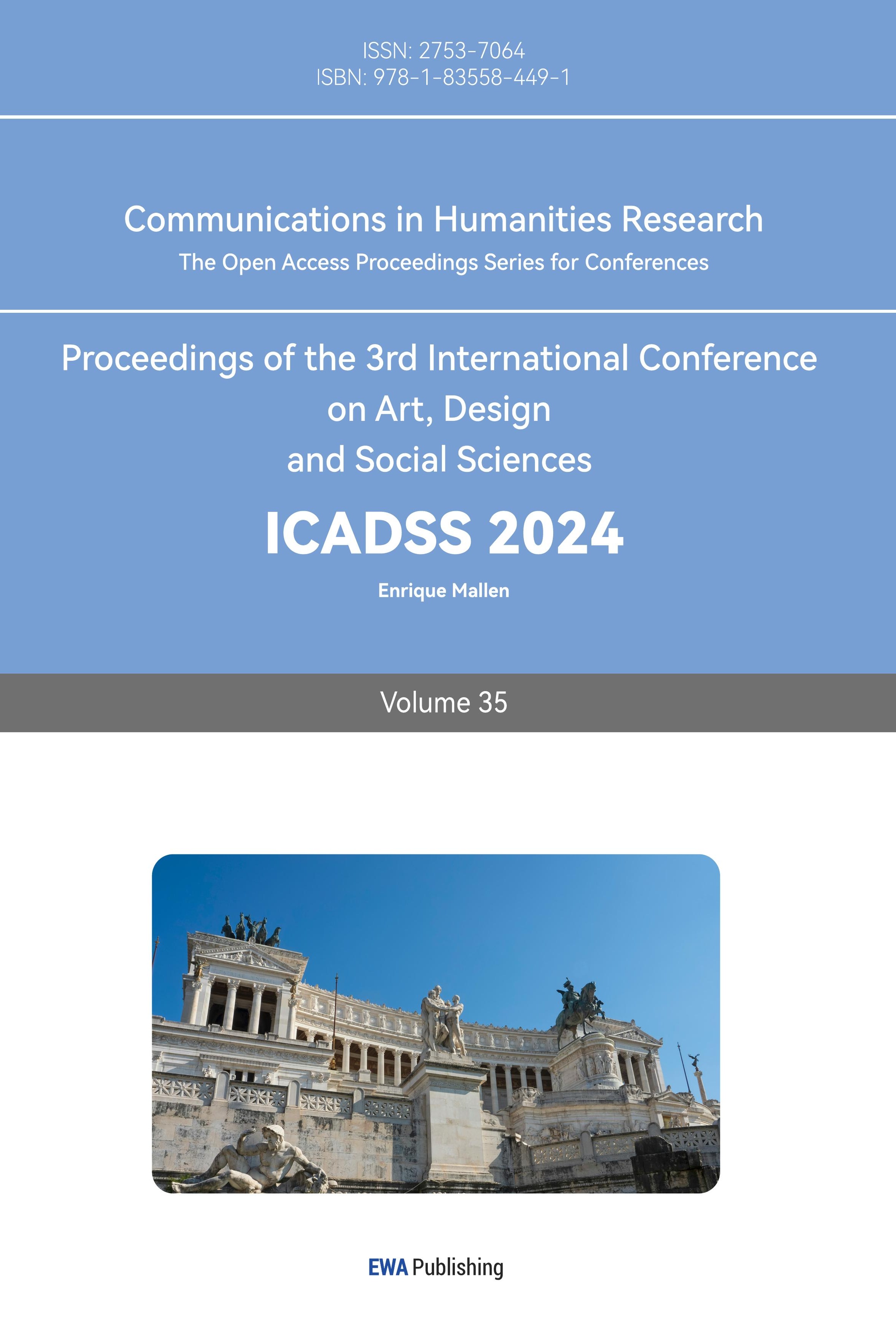

The "toono" (crown) can be divided into two types based on the connection between the circular rim and the supporting poles: connected and inserted. In the connected type, the circular rim and supporting poles are linked by a flexible structure made of leather or sinew, which can be bundled like an umbrella for transport. In the inserted type, the supporting poles directly insert into the circular rim, similar to a mortise and tenon structure, allowing the two parts to be disassembled and packed for transport.

Influenced by ancient Mongolian legends, the "toono" is regarded as a symbol of the sun and, together with the "tulag" (hearth), becomes sacred elements representing the sun and holy fire in Mongolian architecture.

Figure 1: Insert-type toono and Connected-type toono

The "uni" (roof poles) are crucial for the yurt's roof, connecting the toono and the "khana" (walls) in a radiating pattern. The number and length of the uni are determined by the size of the khana, but they must be made from uniform, straight wooden poles. The head of the poles should be smooth and slightly curved to prevent the felt from sagging or collapsing.

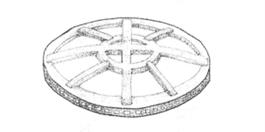

The size of a traditional yurt is mainly determined by the number of khana (wall sections), generally 4, 6, 8, 10, etc., forming a circular wall. When making a single khana, willow strips of similar length and thickness are crossed at equal distances, forming a parallelogram mesh. At the crossing points, they are fixed with leather nails. When connecting khanas, neighboring khanas are tied together with cowhide or camel leather ropes. The height and diameter of the yurt can be adjusted by changing the mesh size of the khana to meet different requirements for roof slope during rainy and windy seasons. More importantly, the khana does not require a solid foundation and is highly foldable, making the yurt easy to assemble, disassemble, and transport, which is ideal for the nomadic lifestyle.

Figure 2: Khana

Traditional yurts originally had only a door frame and a felt door, with wooden doors being used later. For stability and insulation, traditional yurts generally have low khanas, which also limits the door frame height, requiring one to bend when entering. Yurts usually have no locks.

Sometimes, a yurt requires additional "bagana" (columns) for support. As the number of khanas increases, so does the yurt's area and weight, leading to potential material loosening and reduced strength over time. Strong winds can easily bend the toono, especially the connected type. In large yurts with more than eight khanas, two to four columns are usually placed inside, with their upper ends supporting the toono and their lower ends inserted into the wooden frame around the hearth.

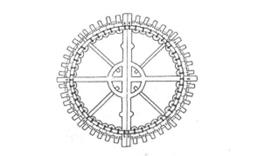

Felt Covering System:

The felt covering of traditional yurts is mainly made of wool or camel hair, providing wind resistance and insulation while being easy to disassemble and transport. According to the covered wooden components, felt can be roughly divided into "erekh" (roof felt), covering the toono; "deever" (top felt), covering the uni; and "tuurga" (wall felt), wrapping around the khana. There is also "uude" (felt door), which, in a certain sequence, is layered over the wooden frame to create a closed indoor space, protecting against wind and snow and maintaining warmth.

Figure 3: Erekh and Deever

Rope System:

The ropes are used to secure the external felt coverings of the yurt, usually made of horsehair and tail hair, preventing the felt from being blown away by the wind and stabilizing the overall shape of the yurt. Based on their use, the ropes can be categorized into those for binding the khana and tuurga, pressing ropes for securing various components, binding ropes for the structure, and the central weight rope tied to the toono.

Plan Layout:

The circular floor plan of a yurt centers around the hearth directly beneath the toono. It is divided into four sections—sacred, secular, female, and male—by two perpendicular lines crossing at the door. The interior furnishings are closely related to these orientations.

Decoration and Color:

Mongolians like to use rich and vibrant colors and patterns to decorate the interior and exterior of their yurts. They have unique color preferences, with commonly used colors including blue, white, red, and yellow, often associated with specific religious contexts and social hierarchy. Typically, the colors are bright, with high saturation and contrast.

The decorative art of Mongolians also features various distinctive patterns, such as cloud motifs, geometric designs, dragons and phoenixes, spirals, and horns. These patterns emphasize bilateral symmetry, central symmetry, the combination of curves and straight lines, and appropriate proportions, showcasing a strong sense of vitality and order.

5.Development of the Yurt

5.1.Xiongnu to Khitan Period

During the Xiongnu to Khitan period, the Mongolian Plateau was home to various nomadic tribes, including the Xiongnu and Donghu during the Warring States and Qin-Han periods; the Xianbei and Gaoran during the Wei, Jin, and Southern and Northern Dynasties periods; the Turks and Uighurs during the Sui and Tang periods; and the Khitans and Jurchens during the Song, Liao, and Jin periods. Other nomadic tribes also spread across the Eurasian steppe. Over a millennium, these tribes left numerous historical records and archaeological remains, but no systematic architectural works or remains for detailed structural analysis.

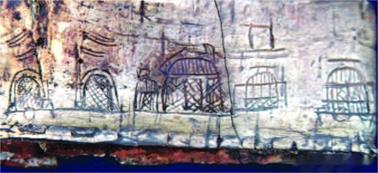

As early as the Western Han period, the Records of the Grand Historian ("Shiji") mentioned "qionglü" (dome-shaped tents) [4]. Subsequent historical texts and poetry often referenced the domed felt tents of northern nomadic tribes. By the Song Dynasty, the Yan Fan Lu mentioned "Tang people's wedding ceremonies often used hundred-child tents...woven with willow strips to form circles, which could be opened and closed...resembling pointed round pavilions" [5]. By this time, the grassland's circular tent structures had formed a relatively complete shape, but their wooden and mobile nature meant few historical remains survived.

Eerdemutu summarized the development of circular tent structures during this period, noting that archaeological painted findings suggest the Xiongnu had a woven dome-like structure similar to a yurt's khana; Northern Wei tomb murals depicted square-shaped yurts with external cloth fences [6]; and Liao Dynasty records of Khitan aristocratic tents showed forms very close to the later Yuan Dynasty tents.

Figure 4: Xiongnu Aristocratic Tomb Painting in the Russian Chalam Valley

From the Xiongnu to Khitan period, the development of grassland tent structures was substantial, with dome-like yurts appearing as early as the Xiongnu period and multiple variations emerging. The yurt, as we know it today, is just one type that continued to evolve.

5.2.Mongol Empire to Yuan and Ming Dynasties

In the 13th century, the Mongol people rose to prominence, and in 1206, Genghis Khan established the Great Mongol State, later known as the Mongol Empire. By the time of Genghis Khan's grandson Möngke Khan's death, the empire spanned Eastern Europe, Western Asia, and Central Asia. After Möngke Khan's death, the empire began to split, eventually forming the Yuan Dynasty and the four khanates, which were nominally vassal states of the Yuan Dynasty [7]. By the mid-14th century, political chaos in the Yuan Dynasty led to the Red Turban Rebellion, and in 1368, Zhu Yuanzhang established the Ming Dynasty, driving the Mongol forces back to the Mongolian Plateau. The khanates subsequently fragmented and fell.

Mongol Tent Structures:

The 13th to 14th centuries can be divided into the unified Mongol period and the subsequent split among the Yuan, Ming, and Central Asian khanates. During this time, the Mongol world was relatively unified and strong, leaving behind more systematic documentation. The yurt structures of this period are relatively clear and comprehensive. From the mid-14th to mid-17th centuries, the Oirat and Tatar powers were in constant conflict, leading to historical turmoil. However, Tibetan Buddhism flourished, merging with Mongolian architectural culture to form unique Tibetan Buddhist temple architectures in the Mongolian region.

Imperial Period Tent Structures:

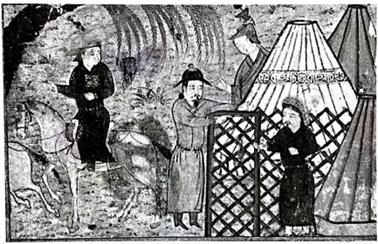

The Secret History of the Mongols, written around 1240 [8], provides detailed descriptions of tent components, types, and furnishings from this period. The circular felt tents of this period can be divided into "Ordo" (large felt tents) and "Gerege" (small and ordinary felt tents). Each part of the felt tent had a Mongolian name, and a structural system similar to modern yurts, comprising khana, uni, and toono, was established.

Figure 5: Erecting an Ordo

During this period, mobile tent structures also included wagon tents, which were transported by oxen, horses, or camels, and could be fixed or temporarily erected on wagons. Unlike simple caravans, wagon tents had complete living functions. The Heida Shilue records, "Oxen, horses, and camels pull their carts, with rooms on the carts for sitting and sleeping, called '帐舆' (tent carts). The four corners of the carts are sometimes supported by poles or crossed boards, used to show respect to the heavens, called '饭食车' (meal carts). They form formations like ants winding and weaving" [9].

Tibetan Buddhist Temples and Yurts:

Starting in the 16th century, political influences led to a wave of Tibetan Buddhism and temple construction across Mongolia. In the process, Tibetan Buddhist and Mongolian architectural cultures merged, forming unique Mongolian temple architectures with distinctive scales, types, and decorations. These can be divided into Han style, Tibetan style, Mongolian style, and mixed styles [2]. The Mongolian style can be further categorized into residential yurts used by lamas, large prayer yurts, and "Gerege Dugong." Gerege Dugong is a tent-like timber structure based on the yurt, but with unique developments in materials, structure, form, and scale. As mobile structures, yurts were also flexibly combined within prayer hall buildings, serving as auxiliary or ceremonial spaces. For instance, during the 1930s, when the Panchen Lama visited Arukorqin Banner, a yurt was erected on top of the Chakchin Hall in Genpi Temple for chanting ceremonies.

Figure 6: Sanggendalai Temple Monks' Small Yurts and A'ershan Temple

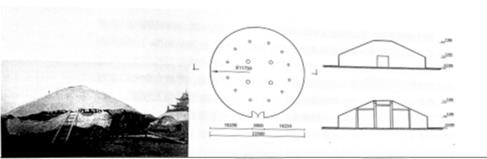

There are two types of yurts in which monks reside: the regular yurts for ordinary lamas and larger yurts for high-ranking monks or living Buddhas. The yurts at Sanggendalai Temple are typical 4-wall yurts, with three lamas living in one yurt according to the temple's regulations[6]. The Buddha hall yurts are specifically for Buddha statues, furnished with cabinets, shrines, and ritual instruments, and are generally not used to accommodate multiple people for chanting, so they are slightly smaller. The chanting hall yurts are usually larger, featuring a system of removable wooden columns with mortise and tenon joints for support, allowing for disassembly and mobility. An example of such a yurt is the Abadai Khan yurt seen by Pozdneev when he visited Erdene Zuu in the 18th year of the Guangxu reign of the Qing Dynasty.

Figure 7: Abadai Khan Yurt: Real Scene and Sectional Diagrams

In addition, there are some monasteries on the Mongolian Plateau that have never built fixed structures and have continuously moved in the form of tent architecture, known as yurt monasteries. These include three basic types: the Huriye, chanting associations, and household temples. The Huriye is a large-scale monastery composed of various yurts, tents, and Ger-style chanting halls, such as the Great Khüree in the early Qing Dynasty. According to records like "Precious Beads," the Great Khüree was built during the Shunzhi period and relocated approximately every three years, continuing until around the end of the Qing Dynasty[10]. Chanting associations and household temple camps typically designate one or several yurts as places for lamas to live and chant, distinguished from ordinary residential yurts by their interior and exterior decorations, reflecting their special functions.

5.3.Qing Dynasty Period

At the end of the Ming Dynasty, Mongolia was divided into several dozen tribes, with the Chahar tribe being the strongest. By the Qianlong period, most Mongolian tribes, except for a few under Russian control, were incorporated into the Qing territory. To effectively manage the Mongolian tribes, the Qing Dynasty established banners (qi) as the basic administrative units. The highest official of a banner was called a jasagh, and clans and tribes were allowed to migrate only within the banner's territory. In Outer Mongolia, several banners formed leagues, with a chief and vice chief responsible for summoning banner meetings.

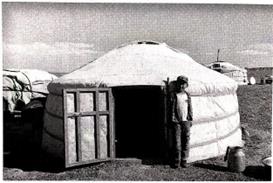

On the Mongolian Plateau during the Qing Dynasty, yurt architecture was widely used as government offices, monasteries, and residences. Representative examples include the large yurts of government offices and the ordinary yurts inhabited by the poor. After the establishment of banners and leagues in Mongolia, official yurt buildings and princely residences appeared on the grasslands. In the early Qing period, these were mostly yurts, but by the mid-Qing period, some banners in eastern Inner Mongolia began to build Chinese-style houses, although yurts remained important ceremonial sites. Large yurts often had eight or more wall sections, symbolizing not only their larger size but also their status and design, typically featuring double doors, columns, and skylight felt pieces. During the mid-Qing period, the skylight felt pieces of monastery and official yurts were often red, while those of ordinary yurts were white. The decorative top felt pieces were particularly symbolic, with unique colors and decorations for high-ranking lamas and noble princes. Compared to official yurts, the yurts of ordinary people were smaller, more simply decorated, and structurally closer to the existing residential yurts. With the advent of photographic records after the Daoguang period, clear data on their design and interior layout became available. Studies show that their dimensions were similar to those of yurts in the first half of the 20th century, with a diameter of 4 meters and a total height of 2.4 meters[6]. Another type was the simpler structure with cloth as the enclosing component, similar to a tent, called the canopy yurt with a circular eave. These were used as camps by Qing emperors, nobles, and high-ranking lamas when traveling. Such nomadic tent settlements were called "cloth cities" and were incorporated into the Qing court's ceremonial system.

Figure 8: Photographs of Buryat Yurts during the Qing Dynasty and Canopy Yurts

Moreover, yurts held significant importance in the Qing Dynasty’s royal palaces and gardens, serving as ceremonial structures for entertaining foreign dignitaries and temporarily housing visiting Mongolian envoys. One of the main locations for setting up large yurts for banquets was the "Shangao Shui Chang" area within the Yuanmingyuan Garden. Today, there are restored yurts in the Yuanmingyuan. The construction of Qing palace yurts was overseen by the Imperial Household Department, while their setup and maintenance were managed by departments like the Military Equipment Institute. Similar to other royal buildings, yurts required model approval by the emperor before their formal construction.

5.4.Modern Period

With the establishment of the Mongolian People's Republic in 1924, significant changes occurred in Mongolian society. The wave of modernization impacted traditional nomadic lifestyles and ancient religious practices on the Mongolian Plateau. Early on, wars and other factors caused some damage to traditional Mongolian architectural techniques, but the original tent-based architectural system largely retained its traditional forms and structures. From the 1950s onwards, yurt production became industrialized, with yurt factories emerging in both Inner Mongolia, China, and Mongolia around the same time. Yurts transitioned into standardized residential buildings, forming the typical modern design. With the shift towards a settled lifestyle, fixed yurts resembling tent-like structures appeared. These residential yurts were often circular with domed roofs and immovable. They utilized materials like willow, grass, reeds, wooden frames, and clay.

6.Conclusion

As a representative of tent-like architecture, yurts have very few historical remnants. Early tent structures gradually evolved into their now-iconic forms and construction principles under various cultural influences. Understanding their development and changes across different periods offers valuable insights into Mongolia’s unique nomadic cultural traditions and the broader evolution of Mongolian architectural culture.

References

[1]. Sigfried Giedion. Space, Time and Architecture: The Growth of a New Tradition [M]. Translated by Wang Jintang, et al. Wuhan: Huazhong University of Science and Technology Press, 2014: 20.

[2]. Zhang Pengju. Research on the Architectural Forms of Tibetan Buddhist Buildings in Inner Mongolia [D]. Tianjin University, 2011.

[3]. Zhou Xiyin, Shi Huading, Wang Xiuru, Meng Fanhao. Analysis of Spatial and Temporal Characteristics and Driving Factors of Land Use Changes on the Mongolian Plateau in the Past 30 Years [J]. Zhejiang Agricultural Journal, 2012, 24(06): 1102-1110.

[4]. Sima Qian (Western Han). Records of the Grand Historian (Second Edition) [M]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 1982: 1289.

[5]. Yongrong, et al. Siku Quanshu Wenyuange. Sub-Department: Comprehensive Works [M]. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House, 2003: 181.

[6]. Eerdemutu. History of Yurt Architecture [M]. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press, 2022.1

[7]. Jiang Peng, Li Jing, compilers; Yao Dali, Li Shan, Qian Wenzhong, et al. A Brief History of China in Fifty Thousand Years: Volume Two [M]. Shanghai: Wenhui Press, 2020.03.

[8]. Yu Dajun. The Secret History of the Mongols [M]. Shijiazhuang: Hebei People's Publishing House, 2001.

[9]. Xu Quansheng. Annotations on the Heida Record [M]. Lanzhou: Lanzhou University Press, 2014: 18.

[10]. Gorradon (Qing). Precious Beads [M]. Edited by Aldazhabu. Hohhot: Inner Mongolia People's Publishing House, 2013: 424.

Cite this article

Zhong,Y. (2024). A Brief History of the Development of Yurt Architecture. Communications in Humanities Research,35,124-132.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Art, Design and Social Sciences

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Sigfried Giedion. Space, Time and Architecture: The Growth of a New Tradition [M]. Translated by Wang Jintang, et al. Wuhan: Huazhong University of Science and Technology Press, 2014: 20.

[2]. Zhang Pengju. Research on the Architectural Forms of Tibetan Buddhist Buildings in Inner Mongolia [D]. Tianjin University, 2011.

[3]. Zhou Xiyin, Shi Huading, Wang Xiuru, Meng Fanhao. Analysis of Spatial and Temporal Characteristics and Driving Factors of Land Use Changes on the Mongolian Plateau in the Past 30 Years [J]. Zhejiang Agricultural Journal, 2012, 24(06): 1102-1110.

[4]. Sima Qian (Western Han). Records of the Grand Historian (Second Edition) [M]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 1982: 1289.

[5]. Yongrong, et al. Siku Quanshu Wenyuange. Sub-Department: Comprehensive Works [M]. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House, 2003: 181.

[6]. Eerdemutu. History of Yurt Architecture [M]. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press, 2022.1

[7]. Jiang Peng, Li Jing, compilers; Yao Dali, Li Shan, Qian Wenzhong, et al. A Brief History of China in Fifty Thousand Years: Volume Two [M]. Shanghai: Wenhui Press, 2020.03.

[8]. Yu Dajun. The Secret History of the Mongols [M]. Shijiazhuang: Hebei People's Publishing House, 2001.

[9]. Xu Quansheng. Annotations on the Heida Record [M]. Lanzhou: Lanzhou University Press, 2014: 18.

[10]. Gorradon (Qing). Precious Beads [M]. Edited by Aldazhabu. Hohhot: Inner Mongolia People's Publishing House, 2013: 424.