1. Introduction

In March 2023, a female vlogger named @fangtouming posted a series of iconic videos on Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok) posted a series of iconic videos in which she mimicked the characteristic gestures of a "Greasy Men," such as giggling, eyebrow-raising, lip-biting, and prolonged staring. Rapidly gaining popularity on Douyin, these videos subsequently inspired numerous female vloggers to craft similar parody videos, dressed in masculine outfits and satirically mimicking various aspects of either the typical portrayal of masculine figures daily or behaviors deemed to be offensive or aggressive towards women, such as overconfidence, mansplaining, mouthiness, and an inappropriate sense of entitlement.

As an increasing number of female vloggers joined this online movement, the imitation diversified, including portrayals of greasy men of different ages, professions, and regions. Women also created a variety of hashtags to connect their video posts. Two of the primary hashtags, #ImitatingGreasyMen (#油男模仿秀#) and #GreasyMen(#油腻男#), had garnered 1.59 billion and 150 million views, respectively, by October 10, 2023. These videos resonated with many female users, as evidenced by the plethora of comments, some of which notably stated, "In this video, I see thousands of men," or "I wish all men would understand that 99.9% of women have experienced this kind of disgusting gaze, and the remaining 0.1% just haven't noticed it" [1].

Originating from Weibo, the buzzword "greasy men" was initially coined to depict middle-aged men known for their lack of attention to personal fitness, unkempt appearance, and crude manner. This term gained popularity because of the viral article "How to Avoid Becoming a Greasy Middle-Aged Man" written by a Chinese writer named Feng Tang[2], sparking various discussions about masculinities and becoming one of the hottest topics towards the 2017 end, which demonstrates its social impact and discursive power. However, when feminist vloggers appropriated this term, they imbued it with new meanings, transforming it into an umbrella term encompassing a spectrum of harmful aspects of masculinity as observed and experienced uncomfortably by women from their perspective. In this context, the gender-reversal performance of #ImitatingGreasyMen signifies a unique wave of feminist activism. It aligns with the global trend of hashtag feminism used to critique the everyday manifestations of toxic masculinity and to protest against gender inequality, as in the case of the #MasculinitySoFragile on Twitter [3].

Despite the significant attention and discussion these videos have garnered on social media, there needs to be more scholarly inquiry into their more profound socio-cultural implications, for example, female gaze, a term that is used as a specific lens through which a woman views, influenced by the women creators whose eyes the audience is looking through [4]. Besides, Chinese households have traditionally practiced the patrilineal system, giving males precedence in a family [5]. In this system, the whole society will undoubtedly support the perspective of gender inequality that restricts women in domestic matters. Alongside the observable national sex ratio imbalance, Chinese women’s hardship in personal life is generally overlooked. Thus, there emerged more female bloggers and vloggers creating articles or videos showing their opinions or observations on male superiority through social media in China.

Therefore, the paper will explore how the female gazes are demonstrated in the vloggers created by the chosen vloggers, imitating the typical patterns of Greasy Men in their videos. The purpose of this paper is to arouse the cognition of society against social-cultural unfairness and call on women to be aware of and get rid of the gender gazes around them. Accordingly, Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) was employed to examine the Top 20 most-viewed videos tagged with #ImitatingGreasyMen, the most-viewed hashtag in the video in order to identify two typical greasy men images and to discuss the contribution of activism expressing women's discontent with their daily struggles with gender inequalities and for the reshaping of public discourse on gender. Research questions are as follows: (1) What do women imitate the typical patterns of greasy-men masculinities in their videos? (2) What commonalities exist in the discourse of #ImitatingGreasyMen? (3) What socio-cultural factors impact women's imitation?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Feminist activism in digital China

The advent of social media has significantly expanded the scope of feminist activism. It provides women abundant avenues to "voice" their perspectives and diversifies the range of voices participating in these discussions. Leveraging the culture of calling out on social media, women have been vocalizing and challenging everyday sexism, misogyny, and sexual violence, which has increased the visibility of gender politics, heralding the arrival of what is termed "Fourth-wave Feminism" [6][7]. The "Fourth wave" of feminism is characterized primarily by digital activism and is marked by features such as "collective voicing, global participation, and a focus on intersectionality" [8]. A quintessential example of this wave is "The Everyday Sexism Project," initiated in 2012 by British feminist writer Laura Bates on her blog. She encouraged women to share their experiences of gender discrimination. The initiative spread to 18 countries and received tens of thousands of responses from women of diverse skin colors, ages, religions, social classes, and professions within less than a year, which surpassed her expectations. These women shared their experiences of gender discrimination in homes, schools, workplaces, public spaces, and mass media [9]. By the end of 2017, the globally sweeping #MeToo movement became one of the most influential feminist discursive actions in recent years, highlighting the powerful mobilizing capacity of the hashtag.

Hashtags serve many functions, signaling topics, connecting personal posts, encouraging participation, and aggregating information under a unified theme. This aggregation enhances the efficiency of information dissemination and organization, enabling users who do not follow each other to form a community akin to shared interests and opinions [10]. By inserting personal posts into hashtag threads, individual women's voices coalesce into a collective voice articulating everyday demands, creating a safe space for women to disclose grievances and resistance[11]. This hashtag-enabled feminist expression is therefore conceptualized as "hashtag feminism," which contributes to feminist consciousness-raising[12], facilitating feminist solidarity [13], and representing a potent strategy for resisting gender inequality[12].

Aligning with the worldwide wave of hashtag feminism, a rising trend in China is that women mobilize hashtags to combat gender discrimination, expose sexual harassment, and protest against menstrual shame [14]. For example, hashtags such as #Anti-appearanceAnxiety and #RejectingAppearanceAnxiety have been used millions of times, marking a feminist response to the destructive impact of aesthetic norms that have long dominated the beauty standard of women's appearance [15]. Moreover, the #MeToo movement initiated collaboratively on various Chinese social media platforms has united survivors, activists, and the public, raising awareness and discussions about sexual harassment and assault throughout society [16][17].

However, like other digital activism and collective actions, Chinese feminist activism suffers from censorship and political oppression[18]. Some feminist social media accounts were permanently banned for "violating relevant national policies and regulations" [19][20]. While it is challenging to confirm whether these accounts closed due to advocating for "MeToo," their steadfast stance against patriarchy and support for feminist actions made them more susceptible to government monitoring and scrutiny. Therefore, scholars underscore the challenges faced by online feminist activists, particularly in the wake of stringent online monitoring [21]. These challenges have led to the evolution of a resilient and adaptive feminist community that employs creative strategies to voice dissent and share stories[22]. Using puns, homonyms, and innovative hashtags becomes a tool for activism and a necessity for survival in the digital realm [23].

2.2. Female gaze and social media

The concept of the female gaze emerges as a profound counter-narrative to the entrenched traditional male gaze, creating a discourse of resistance and rebellion that transcends the conventional frameworks of objectification and sexualization[24]. This notion does not merely act as an oppositional force; it embodies a reclamation of narrative power, challenging the traditional gender norms and expectations that have long dominated the societal gaze[25] . The essence of the female gaze is further enriched by the embodied experiences of women, who navigate the complex terrains of 'the gaze' in their daily interactions[26]. The scrutiny of these embodied experiences, particularly the reactions and responses of women when subjected to the gaze, primarily from male counterparts, unveils the underlying power dynamics and gendered narratives [27]. It serves as a lens through which the intricacies of gendered interactions are explored, shedding light on the female gaze as a form of resistance[28].

Furthermore, the female gaze epitomizes an expression of agency, where women transcend the roles of mere spectators or subjects, evolving into characters or creators with the autonomy to articulate their perspectives and experiences. This expression challenges the traditional gender roles and expectations, heralding a shift towards a more nuanced understanding of gender dynamics[24]. The richness of the female gaze is further encapsulated in its contextual and pluralistic interpretations. Recognizing the female gaze as a plural concept accentuates each individual's unique gaze, which is intricately shaped by personal experiences and social contexts[29]. This pluralism acknowledges the diversity of women's experiences. It underscores the potential of the female gaze as a medium to reflect a vast spectrum of gender-based dissidents and expressions of resistance[30]. This comprehensive understanding of the female gaze contributes to a broader dialogue within feminist and gender studies, propelling a more inclusive and equitable discourse on gender and sexuality.

2.3. Chinese manhood and masculinity

The temperament of Chinese men has always been subject to societal expectations and the influence of globalization, characterized by complexity and diversity. The traditional Chinese concept of masculinity revolves around the dual ideals of "wen" (cultural attainment) and "wu" (physical ability) [31]. More specifically, the Chinese notion of masculinity emphasizes cultural refinement and intelligence over physical strength [32]. At the same time, with the influence of Westernization and modernization, Chinese masculinity has also undergone significant changes [31]. The mutual influence of the Chinese and American film industries has led to changes in the portrayal of men in Chinese mass media, reflecting a more globalized, hybrid masculine ideal[33][34][35]. while the export of popular culture from Japan and Korea has reinforced expectations for men to be gentle, delicate, and emotionally rich, further promoting a "feminization" of the male image [36]. It is evident, therefore, that Chinese masculinity is not a monolithic entity but a diversified form and practice under historical, social, and cultural conditions, constantly adapting to a changing environment. However, these changes are often adjusted to maintain male dominance over women and elite men's dominance over other men[37].

At the same time, in contemporary Chinese society, the construction of the ideal male image is also influenced by neoliberal feminism[38]. Neoliberal feminism advocates for interdependent gender relations and requires men to accept a degree of domestication to accommodate women's needs for balancing family and work[39][40]. However, this idealized feminized Chinese male is still imagined as a wealthy man, containing male power elements [41]. It also emphasizes men's capacity to be attentive to women's needs, therefore fundamentally following a patriarchal logic[41]. The transformative role of female consumer power in shaping the entertainment industry's portrayal of male masculinity in China has also garnered considerable scholarly attention. For instance, Song et al. [41] provide insights into the popularity of "little fresh meat," reflecting a broader social trend that favors a youthful appearance and softer masculinity among Chinese women. These characters often embody an idealized version of masculinity that appeals to a segment of the female audience looking for both escapism and empowerment[42][43].

It should be noted that early research on "masculinity" was primarily focused on white, Western societies, with non-Western societies and cultures often marginalized or overlooked. Although studies on Chinese masculinity have made certain advancements, the impetus for research on Chinese masculinity has also mainly come from Asian populations seeking recognition in Western countries rather than from concepts and practices within Asian societies themselves. This research tendency has led to a deficiency in the study of the conceptions and practices of masculinity within China and other Asian societies, leaving a significant academic void in this field. This study, by focusing on gender performance within Chinese society—especially gender narratives in the new media environment—provides a new perspective for understanding Chinese masculinity. Moreover, by analyzing the dissemination of the hashtag #ImitatingGreasyMen, this research reveals the fluidity and diversity of gender roles, challenging traditional gender notions and definitions of masculinity, and offers important insights into the gender cognition and expression of the younger generation. Therefore, this study not only enriches the academic discourse on Chinese masculinity but also presents new ideas and methods for promoting gender equality and the diversification of gender perception.

3. Research Methods

This research employs Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) to examine the phenomenon of women imitating "greasy men" on Douyin, mainly focusing on videos under the hashtag #ImitatingGreasyMen. The choice of CDA, as advocated by scholars like Fairclough [44] and Van Dijk[45], is driven by its efficacy in exploring the interconnections between discourse, power, and social relations, making it particularly suitable for analyzing media representations about gender. The data collection process for this research is rooted in a purposive sampling strategy, aligning with qualitative research methodologies that emphasize the relevance and insight potential of the data sources. The corpus comprises the top twenty most-viewed videos under the hashtag #ImitatingGreasyMen on Douyin as of October 10, 2023. Selecting the most-viewed videos serves a dual purpose. Firstly, it allows the study to engage with content that has a substantial impact and visibility within the digital sphere, thus capturing a significant portion of the relevant discourse. Secondly, the popularity of these videos suggests that they indicate the salient features and common patterns in the representation of "greasy men" resonating with women users, therefore allowing for an in-depth interpretation of the key trends and characteristics of the studied phenomenon.

The analysis of the videos is structured around Fairclough's three-dimensional framework, which includes the analysis of text, discursive practice, and sociocultural practice. Hence, the whole analytical process can be divided into three phases. The first phase involves a detailed examination of the actual content of the videos, including linguistic features (spoken words, tone, style), non-linguistic elements (visual imagery, body language, gestures), and the overall structure and format of the videos. This phase aims to identify and describe how women portray "greasy men" in these videos. The second phase delves into the interpretative aspects of the videos. This phase critically examines the portrayals' underlying power relations and gendered discourses. It explores how these imitations of "greasy men" interact with established norms and narratives around masculinity, seeking to uncover these representations' deeper meanings and implications. The third phase extends the analysis to the broader sociocultural and ideological contexts. This phase examines the wider societal, cultural, and ideological factors that influence and are influenced by the representations in the videos. It involves exploring themes of gender norms, societal perceptions of masculinity, and the role of digital media in shaping and reflecting public discourse. This stage is crucial for situating the findings within the larger landscape of gender dynamics and digital culture, particularly in the Chinese context.

4. Findings

The analysis of the top twenty most-viewed videos under the hashtag #ImitatingGreasyMen on Douyin revealed two predominant types of “greasy men” being satirically imitated by female vloggers, namely “mansplainer” and “ordinary-but-confident man.”

4.1. Mansplainer

A "mansplainer" (dieweinan, 爹味男) has emerged as a term to denote a self-assumed superior communication style characterized by a patronizing lecture tone and disregard for the perspectives of others, especially women or younger individuals. This particular mode of communication often manifests as a patronizing lecture tone, where the "mansplainer" tends to offer self-centered views and advice, disregarding the perceptions and needs of others, thus exerting a sense of oppression on the other party in the conversation. This term is similar to mansplaining, which connotes a critique of male condescension. In part of the studied sample, female content creators have satirically imitated the demeanor and behavioral patterns of "mansplainer."

They typically don a specific attire, including gold-rimmed glasses and suit trousers, accessorized with luxury items, to depict a "successful middle-aged man." They also mobilize certain mannerisms and catchphrases to highlight their condescending and preachy attitudes and behaviors. Simultaneously, the impersonators extensively use the short video format and the capabilities of the Douyin platform, using editing techniques, music, filters, and special effects to enhance the image of the "mansplainer further." For instance, they might use rapid cuts or zoom to intensify the "mansplainer's" unsettling gestures or expressions, employ humorous background music to underscore the comic effect of the imitation or use filters and special effects to exaggerate certain features or create an ironic atmosphere. One Douyin creator, "Zhou Yingjun," gained popularity for accurately imitating these behaviors, reflecting on the societal expectations of male roles. Often associated with age and experience, these roles are perceived as social capital, fostering a patronizing attitude in men towards women. While ostensibly benevolent, this didacticism conceals underlying intentions of authority and control.

The imitation of "mansplainer" represents a reenactment and satire of traditional gender roles and power structures in China. In patriarchal culture, men are typically expected to play the roles of protectors and providers, and these roles are often associated with increased age, experience, and social status. The "father/dad" role is often an individual's initial encounter with a male authority figure, substantially shaping their early perception of male authority. The term "mansplain" embodies such long-standing societal conditioning, inversely validating the sustained recognition and expectation of the male role, particularly its authoritative nature within the family unit. Men often assume a dominant and authoritative stance, while women tend to conform and remain silent because their contributions are usually dismissed with a polite yet perfunctory laugh. American public writer Rebecca Solnit analyzes the etiology of the "silent woman" phenomenonin her book "Men Explain Things to Me" [46]. She posits that women's silence is not an active choice but a forced suppression. "Men explain things to me and other women, regardless of whether they know what they're talking about," Solnit writes. She likens this patronizing discourse to street harassment, insinuating to women that "this is not their world," thus enforcing their silence. It trains females in self-doubt and self-limitation while nurturing unfounded overconfidence in men. Under a series of complex mechanisms, certain men naturally regard themselves as superior, further entrenching the notion that "she has to learn something from me" as their central theme of communication.

Therefore, women's mockery of mansplaining is a sharp counterattack against patriarchy, cleverly unveiling the hypocrisy of masculine pretense—that behind its seemingly robust exterior lies emptiness, without any more excellent knowledge or ability than women to substantiate it. This confidence has been tolerated because it is built upon societal prejudice. In other words, the satirical imitation of the "mansplainer" by women on platforms like Douyin can be seen as a counterattack against this patriarchal norm, exposing the hollow arrogance behind the façade of masculine confidence. The satirical imitation also reflects women's longing for equality, respect, and diverse interactions and a rejection of any form of unilateral control and oppression.

Figure 1: Screenshots of videos featuring women's imitation of mansplainer

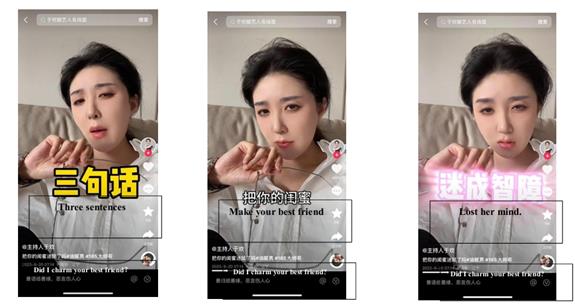

4.2. Ordinary-But-Confident Man

The term “ordinary-but-confident man” was first coined in August 2020 by female stand-up comedian Yang Li, who questioned, “Why are men obviously ordinary but so confident?”This query sparked heated debate among netizens immediately after the show was broadcast, maintaining a high level of controversy. Typically, an “ordinary-but-confident man” refers to men who harbor an inflated self-assessment and exhibit excessive self-confidence despite being average in appearance, income, conversational ability, and cultivation. This archetype is often tied to a toxic male mindset that interprets any action by women around them as an attempt to garner their attention.

In the analyzed Douyin videos, the “ordinary-but-confident man” emerges as a distinctive archetype. As portrayed by female vloggers, this persona often exhibits traits that reflect a deep-seated belief in their superiority, regardless of their actual abilities or achievements. Compared to videos that mimic “mansplainer,” which focuses on the accuracy of attire, the imitation of an “ordinary-but-confident man” emphasizes speech patterns and attitudes. These men are often depicted misinterpreting interactions with women, reading women’s normal behavior as flirtation or rejection as playing hard to get. Common phrases in these imitations include, “Girl, you’re playing hard to get,” “Women always say one thing and mean another,” and “Woman, you have successfully got my attention.” Interestingly, when female Douyin users mimic “ordinary-but-confident man,” they do not emphasize a specific age range. Comparatively, “mansplainer” is often associated with the characteristics of men in particular age groups or stages of life, whereas“ordinary-but-confident man” represents a more general, age-inclusive expectation of males, which highlights the ubiquity of male confidence across all ages.

Figure 2: Screenshots of videos featuring women's imitation of ordinary-but-confident man

The phenomenon of men’s ordinary yet confident demeanor originates from long-standing sociocultural constructs and gender role expectations. Traditional concepts of male superiority give men an inherent basis for confidence independent of external achievements (a form of phallocentrism). Concurrently, the various acquired privileges men enjoy in modern society further reinforce this confidence, allowing men to maintain self-assuredness even without notable competencies, educational qualifications, or emotional intelligence, even though their confidence may primarily rely on their gender advantage. Women, on the other hand, due to historical oppression and gender discrimination, face more significant social and psychological pressures invisibly exact a stricter criterion on their self-assessment of excellence, thereby affecting their confidence. This culturally embedded rigid self-assessment continues to propel men into a cycle of self-satisfaction and excessive confidence.

In this context, women’s satirical imitation of “ordinary-but-confident man” underscores significant sociocultural implications, particularly in evolving gender dynamics and media representation. This trend represents a form of digital activism where humor and mimicry serve as tools for social commentary, challenging traditional gender roles and stereotypes prevalent in Chinese society. By exaggerating the traits of an “ordinary-but-confident man,” these imitations highlight the subtle yet pervasive forms of masculine arrogance often normalized in social interactions. This portrayal reflects a growing awareness and critique of toxic masculinity. It challenges the cultural acceptance of male arrogance as a normative trait, questioning why society often equates male confidence with superiority, irrespective of actual merit. In a culture where traditional gender roles have historically placed men in positions of power and authority, these imitations by women serve as a counter-narrative, highlighting the absurdity and unfairness of these unearned privileges.

Furthermore, the imitation exemplifies that social media can be a powerful medium for feminist expression, enabling women to collectively ridicule and undermine the unwarranted confidence of men, thereby subverting traditional power dynamics. This act of mimicry is not just a form of entertainment; it is a statement against the entrenched patriarchal values that have long dictated gender relations in China. In essence, the imitation of “ordinary-but-confident man” by women on Douyin is more than mere imitation; it is a nuanced form of social critique and a manifestation of the changing landscape of gender relations in the digital era. Through these portrayals, women are reclaiming agency in defining masculinity and reshaping public discourse on gender roles, signaling a transformative era in gender politics.

5. Conclusion

This study uses CDA as the analytical tool and focuses on the intriguing phenomenon of women imitating "greasy men" on Douyin, identifies and analyses two prevalent masculine archetypes: the "mansplainer" and the "ordinary-but-confident man." The primary results are as follows. These archetypes, satirically portrayed by female vloggers, offer a critical lens through which we can view the evolving dynamics of gender relations and the power of digital media as a platform for feminist expression. The "mansplainer," characterized by a patronizing and authoritative demeanor, reflects the entrenched patriarchal structures in Chinese society. Firstly, These imitations reveal a resistance to the authoritative male figure that has dominated the social and familial landscape. Similarly, the "ordinary-but-confident man" archetype captures the pervasive yet often overlooked aspects of toxic masculinity. These imitations highlight the absurdity of unearned male confidence and entitlement, questioning the societal norms that equate Secondly, The popularity and impact of these videos on Douyin also signify a more significant cultural shift. They reflect a growing consciousness among women about the societal constructs that have long undermined their agency. By engaging in this form of mimicry, women assert their voices and reshape the discourse on gender equality. These digital expressions are a powerful tool for feminist activism, allowing women to collectively ridicule and undermine the traditional power dynamics that have favored men. Thirdly, plenty of young females awareness of gender gaze, especially female gaze, indicates that female are tending to choose to self-gaze under the guidance of society or the content from social media, initiating a kind of female gaze that integrates self-exploration and self-empowerment. In the future, with the digital feminism development in China, the study will continue to explore how female activism use social media as a platform for the achievement of Chinese gender equality and for a voice for themselves from both positive and negative sides.

However, it is crucial to recognize that men, too, are victims of societal gender expectations. The male traits that are imitated and mocked are, in fact, reflections of the stereotypical expectations imposed by patriarchy on men. Attacks on the opposite gender group do not facilitate the improvement of the already fractured gender issue and are counterproductive to dismantling the schemes of patriarchy. Instead, such attacks may obscure the necessary collective reflection on this overall predicament. Therefore, on the journey towards gender equality, fostering understanding and dialogue between men and women is essential, rather than merely deepening the divide through imitation and satire. Actual progress in gender equality and social justice can only be achieved when society as a whole reflects and works together to dismantle the patriarchal constraints imposed on all genders.

References

[1]. https://www.huxiu.com/article/1591036.html https://www.huxiu.com/article/219886.html.

[2]. https://weibo.com/ttarticle/x/m/show#/id=2309404167335584902428&_wb_client_=1

[3]. Banet-Weiser, S., & Miltner, K. M. (2016). # MasculinitySoFragile: Culture, structure, and networked misogyny. Feminist media studies, 16(1), 171-174.

[4]. Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Screen, 16, 6-18.http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/screen/16.3.6

[5]. Song, Z. (2008). Flow into eternity: Patriarchy, marriage and socialism in a north China village. University of Southern California.

[6]. Munro, E. (2013).“ Feminism: A fourth wave?”. Political insight, 4(2), 22-25.

[7]. Chamberlain, P. (2017). The feminist fourth wave: affective temporality. Gewerbestrasse, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

[8]. Retallack, H., Ringrose, J., and Lawrence, E. (2016).Fuck your body image: Twitter and instagram feminism in and around school. In J. Coffey, S. Budgeon, and H. Cahill Eds, Learning bodies. Singapore: Springer,85–103.

[9]. Bates, L. (2014). Everyday sexism. London,UK: Simon and Schuster.

[10]. Shao, Y., Desmarais, F., & Kay Weaver, C. (2014). Chinese advertising practitioners’ conceptualisation of gender representation. International Journal of Advertising, 33(2), 329-350.

[11]. Dixon, K. (2014). Feminist online identity: Analyzing the presence of hashtag feminism. Journal of arts and humanities, 3(7), 34-40.

[12]. Clark-Parsons, R. (2018). Building a digital Girl Army: The cultivation of feminist safe spaces online. New Media & Society, 20(6), 2125-2144.

[13]. Rentschler, C. A., & Thrift, S. C. (2015). Doing feminism in the network: Networked laughter and the ‘Binders Full of Women’meme. Feminist theory, 16(3), 329-359.

[14]. Wu, X. (2020). “Straight Man Cancer”: The Discursive Representation and Backlash of Sexism on Chinese Internet. Gender Equality in Changing Times: Multidisciplinary Reflections on Struggles and Progress, 181-201.

[15]. Lazuka, R. F., Wick, M. R., Keel, P. K., & Harriger, J. A. (2020). Are we there yet? Progress in depicting diverse images of beauty in Instagram’s body positivity movement. Body image, 34, 85-93.

[16]. Han, X. (2021). Uncovering the low-profile# MeToo movement: Towards a discursive politics of empowerment on Chinese social media. Global Media and China, 6(3), 364-380.

[17]. Lin, Z., & Yang, L. (2019). Individual and collective empowerment: Women's voices in the# MeToo movement in China. Asian Journal of Women's Studies, 25(1), 117-131.

[18]. Yang, Y. (2022). When positive energy meets satirical feminist backfire: Hashtag activism during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Global Media and China, 7(1), 99-119.

[19]. Yin, S., & Sun, Y. (2021). Intersectional digital feminism: Assessing the participation politics and impact of the MeToo movement in China. Feminist Media Studies, 21(7), 1176-1192.

[20]. Lindberg, F. (2021). Women’s Rights in China and Feminism on Chinese Social Media. Institute for Security & Development Policy.

[21]. Núñez Puente, S. (2011). Feminist cyberactivism: Violence against women, internet politics, and Spanish feminist praxis online. Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, 25(03), 333-346.

[22]. Mendes, K., Ringrose, J., & Keller, J. (2019). Digital feminist activism: Girls and women fight back against rape culture. Oxford University Press.

[23]. Jeong, E., & Lee, J. (2018). We take the red pill, we confront the DickTrix: Online feminist activism and the augmentation of gendered realities in South Korea. Feminist Media Studies, 18(4), 705-717.

[24]. Li, X. (2020). How powerful is the female gaze? The implication of using male celebrities for promoting female cosmetics in China. Global Media and China, 5(1), 55-68.

[25]. Skelton, C. (2002). Constructing dominant masculinity and negotiating the'male gaze'. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 6(1), 17-31.

[26]. Calogero, R. M. (2004). A test of objectification theory: The effect of the male gaze on appearance concerns in college women. Psychology of women quarterly, 28(1), 16-21.

[27]. Nielsen, R. A. (2020). Women's authority in patriarchal social movements: the case of female Salafi preachers. American Journal of Political Science, 64(1), 52-66.

[28]. Burke, E. (2006). Feminine visions: Anorexia and contagion in pop discourse. Feminist Media Studies, 6(3), 315-330.

[29]. Glapka, E. (2018). ‘If you look at me like at a piece of meat, then that’sa problem’–women in the center of the male gaze. Feminist Poststructuralist Discourse Analysis as a tool of critique. Critical Discourse Studies, 15(1), 87-103.

[30]. Martin, P. Y. (2006). Practising gender at work: Further thoughts on reflexivity. Gender, work & organization, 13(3), 254-276.

[31]. Louie, K. (2014). Chinese masculinity studies in the twenty-first century: Westernizing, Easternizing and globalizing wen and wu. NORMA: International Journal for Masculinity Studies, 9(1), 18-29.

[32]. Louie, K. (2002). Theorising Chinese masculinity: Society and gender in China. Cambridge University Press.

[33]. Chan, J. (2020). Chinese American Masculinities: From Fu Manchu to Bruce Lee. Routledge.

[34]. Szeto, K. Y. (2011). The Martial Arts Cinema of the Chinese Diaspora: Ang Lee, John Woo, and Jackie Chan in Hollywood. SIU Press.

[35]. Chow, Y. F. (2008). Martial arts films and Dutch–Chinese masculinities: Smaller is better. China Information, 22(2), 331-359.

[36]. IidaHuman Rights Watch (HRW). (2020). "China: Online Gender-based Violence Targets Women." https://www.hrw.org/

[37]. Donaldson, M. (1993). What is hegemonic masculinity?. Theory and society, 643-657.

[38]. Peng, A. Y. (2021). Neoliberal feminism, gender relations, and a feminized male ideal in China: A critical discourse analysis of Mimeng’s WeChat posts. Feminist Media Studies, 21(1), 115-131.

[39]. Yang, F. (2023). Post-feminism and chick flicks in China: Subjects, discursive origin and new gender norms. Feminist Media Studies, 23(3), 1059-1074.

[40]. Rottenberg, C. (2014). The rise of neoliberal feminism. Cultural studies, 28(3), 418-437.

[41]. Song, G., & Hird, D. (2014). Men and masculinities in contemporary China. In Men and Masculinities in Contemporary China. Brill.

[42]. Zhang, X. (2019). Narrated oppressive mechanisms: Chinese audiences’ receptions of effeminate masculinity. Global Media and China, 4(2), 254-271.

[43]. Katila, S., & Eriksson, P. (2013). He is a firm, strong‐minded and empowering leader, but is she? Gendered positioning of female and male CEOs. Gender, Work & Organization, 20(1), 71-84.

[44]. Fairclough, N. (2015). Language and Power. Longman.

[45]. Van Dijk, T. A. (2013). Discourse and Knowledge: A Sociocognitive Approach. Cambridge University Press.

[46]. Solnit, R. (2014). Men explain things to me. Haymarket books.

Cite this article

Liu,Y. (2024). A Mirror for Men? Feminist Activism of #ImitatingGreasyMen in China. Communications in Humanities Research,40,25-35.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. https://www.huxiu.com/article/1591036.html https://www.huxiu.com/article/219886.html.

[2]. https://weibo.com/ttarticle/x/m/show#/id=2309404167335584902428&_wb_client_=1

[3]. Banet-Weiser, S., & Miltner, K. M. (2016). # MasculinitySoFragile: Culture, structure, and networked misogyny. Feminist media studies, 16(1), 171-174.

[4]. Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Screen, 16, 6-18.http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/screen/16.3.6

[5]. Song, Z. (2008). Flow into eternity: Patriarchy, marriage and socialism in a north China village. University of Southern California.

[6]. Munro, E. (2013).“ Feminism: A fourth wave?”. Political insight, 4(2), 22-25.

[7]. Chamberlain, P. (2017). The feminist fourth wave: affective temporality. Gewerbestrasse, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

[8]. Retallack, H., Ringrose, J., and Lawrence, E. (2016).Fuck your body image: Twitter and instagram feminism in and around school. In J. Coffey, S. Budgeon, and H. Cahill Eds, Learning bodies. Singapore: Springer,85–103.

[9]. Bates, L. (2014). Everyday sexism. London,UK: Simon and Schuster.

[10]. Shao, Y., Desmarais, F., & Kay Weaver, C. (2014). Chinese advertising practitioners’ conceptualisation of gender representation. International Journal of Advertising, 33(2), 329-350.

[11]. Dixon, K. (2014). Feminist online identity: Analyzing the presence of hashtag feminism. Journal of arts and humanities, 3(7), 34-40.

[12]. Clark-Parsons, R. (2018). Building a digital Girl Army: The cultivation of feminist safe spaces online. New Media & Society, 20(6), 2125-2144.

[13]. Rentschler, C. A., & Thrift, S. C. (2015). Doing feminism in the network: Networked laughter and the ‘Binders Full of Women’meme. Feminist theory, 16(3), 329-359.

[14]. Wu, X. (2020). “Straight Man Cancer”: The Discursive Representation and Backlash of Sexism on Chinese Internet. Gender Equality in Changing Times: Multidisciplinary Reflections on Struggles and Progress, 181-201.

[15]. Lazuka, R. F., Wick, M. R., Keel, P. K., & Harriger, J. A. (2020). Are we there yet? Progress in depicting diverse images of beauty in Instagram’s body positivity movement. Body image, 34, 85-93.

[16]. Han, X. (2021). Uncovering the low-profile# MeToo movement: Towards a discursive politics of empowerment on Chinese social media. Global Media and China, 6(3), 364-380.

[17]. Lin, Z., & Yang, L. (2019). Individual and collective empowerment: Women's voices in the# MeToo movement in China. Asian Journal of Women's Studies, 25(1), 117-131.

[18]. Yang, Y. (2022). When positive energy meets satirical feminist backfire: Hashtag activism during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Global Media and China, 7(1), 99-119.

[19]. Yin, S., & Sun, Y. (2021). Intersectional digital feminism: Assessing the participation politics and impact of the MeToo movement in China. Feminist Media Studies, 21(7), 1176-1192.

[20]. Lindberg, F. (2021). Women’s Rights in China and Feminism on Chinese Social Media. Institute for Security & Development Policy.

[21]. Núñez Puente, S. (2011). Feminist cyberactivism: Violence against women, internet politics, and Spanish feminist praxis online. Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, 25(03), 333-346.

[22]. Mendes, K., Ringrose, J., & Keller, J. (2019). Digital feminist activism: Girls and women fight back against rape culture. Oxford University Press.

[23]. Jeong, E., & Lee, J. (2018). We take the red pill, we confront the DickTrix: Online feminist activism and the augmentation of gendered realities in South Korea. Feminist Media Studies, 18(4), 705-717.

[24]. Li, X. (2020). How powerful is the female gaze? The implication of using male celebrities for promoting female cosmetics in China. Global Media and China, 5(1), 55-68.

[25]. Skelton, C. (2002). Constructing dominant masculinity and negotiating the'male gaze'. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 6(1), 17-31.

[26]. Calogero, R. M. (2004). A test of objectification theory: The effect of the male gaze on appearance concerns in college women. Psychology of women quarterly, 28(1), 16-21.

[27]. Nielsen, R. A. (2020). Women's authority in patriarchal social movements: the case of female Salafi preachers. American Journal of Political Science, 64(1), 52-66.

[28]. Burke, E. (2006). Feminine visions: Anorexia and contagion in pop discourse. Feminist Media Studies, 6(3), 315-330.

[29]. Glapka, E. (2018). ‘If you look at me like at a piece of meat, then that’sa problem’–women in the center of the male gaze. Feminist Poststructuralist Discourse Analysis as a tool of critique. Critical Discourse Studies, 15(1), 87-103.

[30]. Martin, P. Y. (2006). Practising gender at work: Further thoughts on reflexivity. Gender, work & organization, 13(3), 254-276.

[31]. Louie, K. (2014). Chinese masculinity studies in the twenty-first century: Westernizing, Easternizing and globalizing wen and wu. NORMA: International Journal for Masculinity Studies, 9(1), 18-29.

[32]. Louie, K. (2002). Theorising Chinese masculinity: Society and gender in China. Cambridge University Press.

[33]. Chan, J. (2020). Chinese American Masculinities: From Fu Manchu to Bruce Lee. Routledge.

[34]. Szeto, K. Y. (2011). The Martial Arts Cinema of the Chinese Diaspora: Ang Lee, John Woo, and Jackie Chan in Hollywood. SIU Press.

[35]. Chow, Y. F. (2008). Martial arts films and Dutch–Chinese masculinities: Smaller is better. China Information, 22(2), 331-359.

[36]. IidaHuman Rights Watch (HRW). (2020). "China: Online Gender-based Violence Targets Women." https://www.hrw.org/

[37]. Donaldson, M. (1993). What is hegemonic masculinity?. Theory and society, 643-657.

[38]. Peng, A. Y. (2021). Neoliberal feminism, gender relations, and a feminized male ideal in China: A critical discourse analysis of Mimeng’s WeChat posts. Feminist Media Studies, 21(1), 115-131.

[39]. Yang, F. (2023). Post-feminism and chick flicks in China: Subjects, discursive origin and new gender norms. Feminist Media Studies, 23(3), 1059-1074.

[40]. Rottenberg, C. (2014). The rise of neoliberal feminism. Cultural studies, 28(3), 418-437.

[41]. Song, G., & Hird, D. (2014). Men and masculinities in contemporary China. In Men and Masculinities in Contemporary China. Brill.

[42]. Zhang, X. (2019). Narrated oppressive mechanisms: Chinese audiences’ receptions of effeminate masculinity. Global Media and China, 4(2), 254-271.

[43]. Katila, S., & Eriksson, P. (2013). He is a firm, strong‐minded and empowering leader, but is she? Gendered positioning of female and male CEOs. Gender, Work & Organization, 20(1), 71-84.

[44]. Fairclough, N. (2015). Language and Power. Longman.

[45]. Van Dijk, T. A. (2013). Discourse and Knowledge: A Sociocognitive Approach. Cambridge University Press.

[46]. Solnit, R. (2014). Men explain things to me. Haymarket books.