1. Introduction

In the decades following the end of the Second World War, the Japanese economy has been a subject of study worth exploring. Beginning in the 1950s, Japan became the first country in East Asia to embark on an economic recovery. During those decades, with the assistance of the United States and Japan's regulation, it created an economic miracle that enabled it to leapfrog to the status of a developed country and to become the world's second-largest economy in the last century. In addition, Japan did experience faster overall economic growth from the 1950s through the 1980s, before the Plaza Accord, with increases in GDP, employment, and other areas. However, in the long run, the economic growth brought to Japan by the U.S. was often a double-edged sword. In the 1980s, Japan signed the Plaza Accord with the United States, and since then, in the 1990s, Japan's economy has taken a different turn. During that period, a bubble economy emerged in Japan, which burst, and the economic situation was not optimistic. So far, Japan's economy has grown slowly, moving from the world's second-largest economy to the world's third largest. Is it possible that the signing of the Plaza Accord has led to such a drastic change in Japan's economic growth? The following three sections in this paper describes Japan's economic growth and its turning points and based on this, the three major industries, the share of consumption in GDP , and why the United States approached Japan for the Plaza Accord. The final section will discuss the lessons to be learnt by summarizing Japan's economic development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Korean War & Post-War Economic Growth

In the 1950s, the United States led the United Nations forces in the Korean War. During this period, the United States began to buy strategic materials in Japan, and the Korean War was the beginning of Japan's post-war economic growth. It was even considered a boon to the Japanese economy. A bank president at the time surmised that the United States would invest a lot of military spending in Japan during the war, and the Tokyo stock market also saw unexpected growth at the time, which made the Japanese begin to be optimistic about economic recovery. Statistics showed that during the outbreak of the Korean War, Japan's average annual GDP growth began to exceed 10%, the industrial index rose to 142, and industrial output increased by 50%. At that time, the United States spent nearly $3 billion on Japanese war materials and services, which fully confirmed Dingman's suspicion that the Korean War was an economic gift to Japan. And in one country, that amount of money was equivalent to 60% of the US investment in non-war countries, along with increased employment. William Borden also argues that the Korean War was a decisive event in the revival and repositioning of Japanese trade. With this growth, Japan became economically dependent on the United States [1].

After the end of the Korean War, Japan began to create a post-war economic miracle. This could not be separated from the fact that Japan's policies back then influenced the economy, and by 1954, Japan's policy of developing the manufacturing sector was a huge success. Studies have shown that the core of Japan's success was mainly the economic reforms that tilted the mode of production (the production of raw materials) and used it to produce final products. Then there was the fact that Japan started recruiting female employees, which increased the overall participation rate and added enough labor for production. Japan's income doubling program and the Basic Law for Agriculture, introduced between 1961 and 1970, were also successful. By 1970, Japan's real GDP growth rate had reached 11.6%, and the former was also responsible for increasing per capita labor output, while the latter improved overall efficiency [2]. From 1955 to 1971, there was an increase in employment but a slower increase in the labor index. And during this period, the factors of production, i.e., capital and intermediate goods, became the source of Japan's economic growth. In addition to manufacturing, productivity changes in agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and mining were the dominant factors, while the contribution of water, electricity, gas, transport, trade, and services was low, and even the contribution of finance, real estate, and construction was almost nil. In the estimation of real products, it may be the size of the field that is the problem [3]. Through Japan's post-war economic miracle, although there was the fact that Japan had US aid and then developed policies for economic growth, it also indirectly showed that Japan would be economically dependent on the US, as just stated. However, the help brought by the United States was not long-lasting growth, which would be like a dagger in the core of Japan's economy.

2.2. Plaza Accord & Bubble Economy

In the 1980s, the fiscal deficit of the United States widened, and an attempt was then made to reduce it by devaluing the US dollar. As a result, the United States got Japan to sign an agreement with it at the Plaza Hotel, and this was the Plaza Accord. Germany signed the Plaza Accord as well, but Germany did not experience the economic decline that Japan did in the 1990s. The U.S. signed the Plaza Accord with Japan because Japan's post-war growth was rapid, and its purchasing power parity far exceeded that of the United States. Therefore, the US had to deal with its deficits while at the same time preventing Japan from continuing to grow [4]. After the Plaza Accord, the exchange rate of the yen began to appreciate rapidly; before that, 240 yen could only be exchanged for 1 US dollar, but after that , 1 US dollar could be exchanged for 216 yen. It can be shown that the yen appreciated by 10 % at that time, and by the end of 1985, 200 yen could be exchanged for 1 dollar, and this situation has continued. Even to the back, the yen exchange rate breaks through 190 yen per dollar, while the Bank of Japan is intervening in reverse at this time, the Bank of Japan began to cut interest rates [5]. Some people believe that the Plaza Accord is a conspiracy theory, and the reason for this may be related to the economic situation that emerged in Japan after the Plaza Accord. As a result, it is believed that the United States destroyed the Japanese economy. During the period 1987-1989, Japan saw the advent of the bubble economy [6].

During the bubble economy, Japan's total bank loans increased from 135 trillion to 376 trillion yen, while the nominal GDP growth rate was maintained at around 5%. Even between 1981 and 1985, credit in Japan increased by about 26 trillion yen. And between 1986 and 1990, it increased by an annual average of 46 trillion yen. The ratio of total bank loans to GDP is even more incomprehensible. This situation led to a surge in land prices in Japan, and stock prices also rose by a large margin. This was a serious problem of internal and external imbalance, but the Japanese government, having identified this problem, believed that financial liberalization could regulate it. At that time, Japan had a floating exchange rate system. As a result, instead of adopting macroprudential financial regulation, Japan adopted an accommodative monetary policy [7]. If coupled with the interest rate cuts mentioned earlier, it would probably have led to the bursting of the Japanese bubble in the 1990s. Base money began to rise sharply in the 1990s with the use of easy monetary policy and in the aftermath of the Japanese bubble economy. This was because monetary policy in Japan began to tighten relatively, and the Bank of Japan attempted to burst the bubble [8]. However, the bursting of the Japanese bubble economy was followed by massive bank failures and a sustained fall in land prices, coupled with a decline in the effectiveness of Japan's fiscal policy, an aging population, and a shift in budgetary spending from the central government to local governments. This also led to overcapacity in Japan, which led to a slowdown in technological development, and a high exchange rate that caused some profitable companies to leave Japan, which also led to a reduction in domestic production. As a result, it will be difficult for the Japanese economy to rebound for decades [9].

The U.S. prompting Japan to sign the Plaza Accord can be considered a reason. Still, the main thing is the economic activities of the Japanese government after the signing of the Plaza Accord. Japan's excessive dependence on the US will only result in its inability to compete with the US in terms of policy after the bubble bursts and its inability to break away from the US economically. Therefore, taking the above studies together, there is still insufficient evidence to prove that the Plaza Accord was the direct cause of Japan's economic recession after the 1990s.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

As to whether the Plaza Accord was the main reason for the slow growth of the Japanese economy, it is possible to obtain a relatively satisfactory result by examining the data related to finance, the three major industries, agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and consumption during that period. However, by referring to the relationship between finance and economic growth and the impact of manufacturing among the three major industries on growth, the data and analysis results may not be very practical for Japan's economic situation [10]. This is because, after the Plaza Accord in the last century, Japan did not necessarily start in the financial world with the yen exchange rate and bank interest rates falling. As for the manufacturing industry, although it is said that Japan reformed the manufacturing industry after the war, it cannot be said that the situation of the manufacturing industry turned sharply downward during the 1990s. Therefore, it may be for developing countries, while developed countries like Japan need to consider other factors [11].

This study searched the CEIC Database for data related to Japan's GDP, central bank interest rate, exchange rate, three major industries, and consumption. By consolidating the data, some relevant line graphs as well as pie charts were produced. Among them, the line graphs were studied to identify the annual growth trend of the exchange rate and bank rate concerning the GDP year. The graphs were also used to derive whether the growth was in line with the growth of GDP and focused on observing the situation after the 1980s. Next, for the three major industries, the main study is on their share of GDP. At the same time, some pie charts are produced for further study. The main purpose of this dominance is to determine which of the three major industries dominates the GDP. By looking at the three major industries, it is possible to determine which industry Japan excelled in at that time and to explain why. Finally, Japanese consumption data is still examined through line graphs. This panel focuses on consumption and GDP to see if GDP is also affected by consumption.

3.2. Results

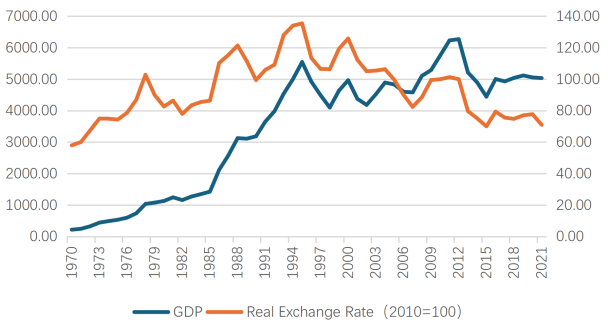

Figure 1 shows the growth trend between the exchange rate and GDP, where the growth of the exchange rate was accompanied by GDP growth. This indicates that the exchange rate continued to grow before and after the Plaza Accord and peaked in 1995. After that, although there was still growth, it could no longer reach its peak.

Figure 1: Trend of exchange rate and GDP

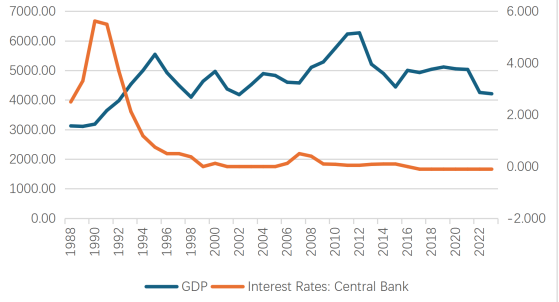

In the decades following the bubble economy of the 1990s, although it is said that there were fluctuations at that time, it is not enough to show that the Plaza Accord led to a serious decline in the exchange rate and GDP. Turning now to bank interest rates, they were still rising in the early 1990s but only peaked again in 1990. After that, they rarely peaked and kept falling. While GDP was still growing in the mid- to late 1990s, interest rates have been falling almost continuously. This can be seen in the trend of interest rates and GDP shown in Figure 2. Through the different scenarios of interest rates and exchange rates, it is easy to see that after the signing of the agreement, Japan saw that the exchange rate had been growing, but the Japanese government at that time did not take any measures to cope with the rising exchange rate, and it was only when the exchange rate of the Japanese yen had risen to an unfathomable level that Japan continued to adopt the loose monetary policy, which led to a policy blunder. It was this mistake, coupled with the Japanese government's belief that the continued rise in the exchange rate was a good thing, that led Japan to allow its companies to buy large amounts of overseas assets. If Japanese companies do not invest enough, the government will cut interest rates. However, the decline in interest rates may also be due to the emergence of a bubble after Japanese companies bought in large quantities, and the funds from Japanese companies' overseas investments during this period cannot be recovered. As mentioned earlier, although Japan tried to tighten policy during the bubble economy, it had little effect.

Figure 2: Trend of interest rate and GDP

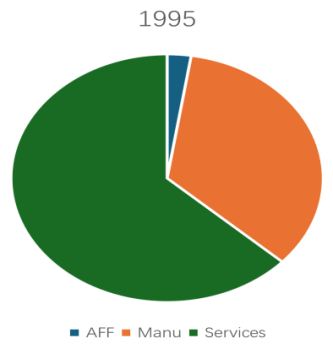

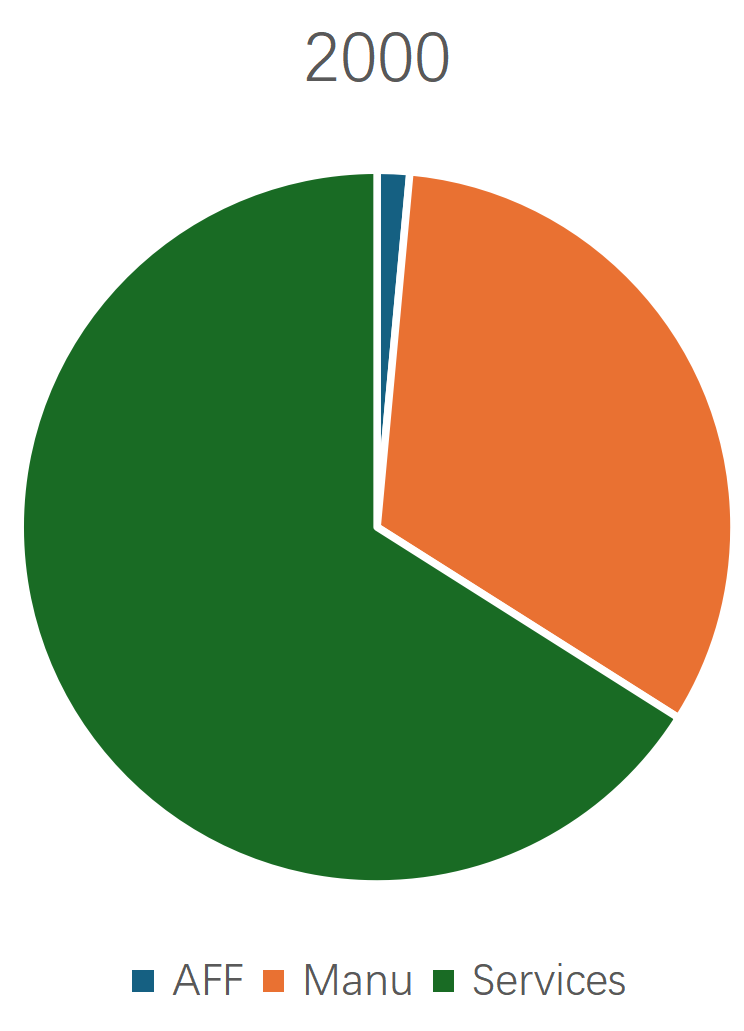

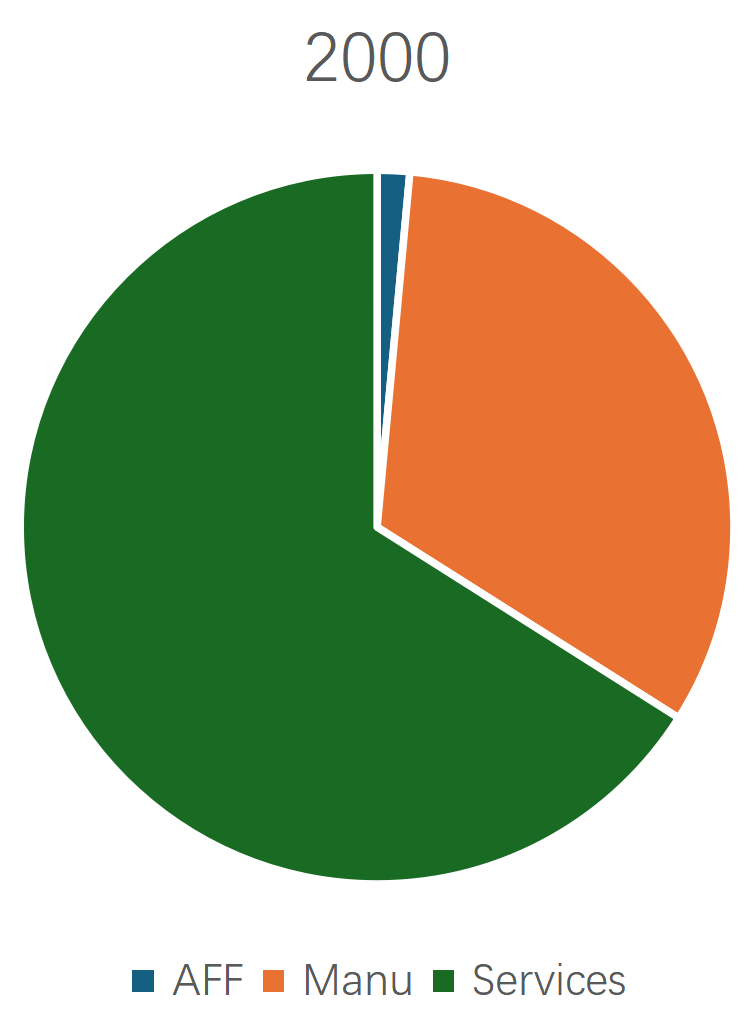

Figure 3-5 examines the share of manufacturing, services, agriculture, forestry and fisheries in GDP. This section is mainly needed to show which of the three major industries has been growing and which has been less important before and after the Plaza Accord. In three different years, Japan's service sector has been at the forefront of GDP, while manufacturing, agriculture, forestry and fisheries have not been as significant. As a result, after Japan signed the Plaza Accord, many large Japanese companies moved their factories out of the country. This has led to the fact that the factories of the large enterprises mentioned earlier are no longer on the mainland, while the banks are reluctant to give loans to small-scale producers who remain on the mainland. This has led to a hollowing out of industry in Japan, and the contribution of the service sector has exceeded that of manufacturing. This led to the gradual de-industrialization of Japan, which could only be engaged in the service sectors [12].

Figure 5: Shares of three major industries in GDP in 2012

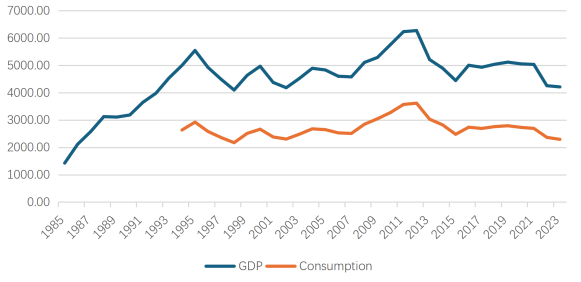

Figure 6 shows the growth trend of consumption and GDP, which are components of GDP. GDP is also growing with the increase in consumption. Consumption increased in 1994 and 1995 and peaked in 2011-2012. However, it fluctuated a lot after 2012 and barely grew. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Japan's economic bubble burst. After the agreement was signed, Japan encouraged its citizens to buy many properties overseas, which were rarely repossessed by the seller's country, resulting in a break in the capital chain of Japan, which is almost the same as the situation in Figure 2, basically no return on investment.

Figure 6: Trends of Consumption and GDP

4. Conclusion

It took Japan thirty years to experience economic recovery and decline, Japan's erroneous economic behavior and monetary policy gave Japan a weighty lesson. Japan's loose monetary policy and constant interest rate cuts in the purchase of overseas assets caused the Japanese bubble to burst. This is completely different from the situation in Germany, which kept raising interest rates after signing to save itself from being like Japan. Therefore, Japan's experience shows that you should never do the opposite in the policies. The bursting of the Japanese economic bubble in the 1990s made it almost impossible for Japan to regulate itself for three decades, and Japan lost three decades of opportunity for economic development, which came to be known as Japan's Lost Thirty Years. This has brought some warnings to other Asian countries. Firstly, they should not think that the gifts of others can help them develop in the long run. They should maintain good economic independence and should not rely on others. Secondly, after signing the agreement, one should not make a policy mistake if one sees that one's exchange rate has risen to an incomprehensible level. Thirdly, it does not lead to the hollowing out of industries. Many profitable enterprises in Japan have relocated their factories out of Japan, resulting in the proportion of industry in GDP being too low. Lastly, it is important not to over-buy overseas assets, which may result in the money invested not being recovered in the first place, which is why the Japanese economy has seen the bursting of the property bubble because this leads to non-performing loans and financial instability. In addition to the above, Japan needs to empower banks to be willing to lend to small businesses that stay in their home countries, which could provide some relative relief from the hollowing out of the industry. The future state of the Japanese economy remains worrying, and it will take a long time for Japan to resolve the trauma caused by the bursting of the bubble economy. If Japan were to repeat the mistakes of the previous century, it would only be a matter of time before there was a second bubble in a few years.

References

[1]. Dingman, R. (1993) The Dagger and the Gift: The Impact of the Korean War on Japan. Journal of American-East Asian Relations, 2(1), 29–55. doi:10.1163/187656193x00077.

[2]. Tongye Wang. (2021) Analysis on the Influential Factors of Japanese Economy. 2020 2nd International Academic Exchange Conference on Science and Technology Innovation (IAECST 2020), 27 January, pp.4.

[3]. Nishimizu, M., & Hulten, C. R. (1978) The Sources of Japanese Economic Growth: 1955-71. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 60(3), 351. doi:10.2307/1924160

[4]. Ken Dow. (2020) How the Plaza Accord helped the US destroy the Japanese economy and how the US is doing it again to China. https://kendawg.medium.com/how-the-plaza-accord-helped-the-us-destroy-the-japanese-economy-b4b24c20a9af

[5]. Ito, Takatoshi. (2015) The Plaza Agreement and Japan: Reflection on the 30th year Anniversary. https://www.bakerinstitute.org/research/plaza-agreement-and-japan-reflection-30th-year-anniversary

[6]. Jeffrey Frankel. (2015) The Plaza Accord, 30 Years Later, December, Working Paper 21813.

[7]. Kang, M. (2017) The Confidence Trap: Japan’s Past Bubble and China’s Recent Bubble. New Political Economy, 23(1), 1–26. doi:10.1080/13563467.2017.1321626

[8]. Dekle, R., & Hamada, K. (2015). Japanese monetary policy and international spillovers. Journal of International Money and Finance, 52, 175–199.

[9]. Yoshino, N., & Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. (2016) Causes and Remedies of the Japan’s Long-lasting Recession: Lessons for China. China & World Economy, 24(2), 23–47.

[10]. Roubini, N., & Sala-i-Martin, X. (1992). Financial repression and economic growth. Journal of Development Economics, 39(1), 5–30. doi:10.1016/0304-3878(92)90055-e.

[11]. Szirmai, A., & Verspagen, B. (2015). Manufacturing and economic growth in developing countries, 1950–2005. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 34, 46–59.

[12]. Lee, J.W., & McKibbin, W. J. (2018) Service sector productivity and economic growth in Asia. Economic Modelling. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2018.05.018.

Cite this article

Dong,R. (2024). Japan's Lost Thirty Years: From Post-War Miracle to Bursting Bubble. Communications in Humanities Research,40,61-67.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Dingman, R. (1993) The Dagger and the Gift: The Impact of the Korean War on Japan. Journal of American-East Asian Relations, 2(1), 29–55. doi:10.1163/187656193x00077.

[2]. Tongye Wang. (2021) Analysis on the Influential Factors of Japanese Economy. 2020 2nd International Academic Exchange Conference on Science and Technology Innovation (IAECST 2020), 27 January, pp.4.

[3]. Nishimizu, M., & Hulten, C. R. (1978) The Sources of Japanese Economic Growth: 1955-71. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 60(3), 351. doi:10.2307/1924160

[4]. Ken Dow. (2020) How the Plaza Accord helped the US destroy the Japanese economy and how the US is doing it again to China. https://kendawg.medium.com/how-the-plaza-accord-helped-the-us-destroy-the-japanese-economy-b4b24c20a9af

[5]. Ito, Takatoshi. (2015) The Plaza Agreement and Japan: Reflection on the 30th year Anniversary. https://www.bakerinstitute.org/research/plaza-agreement-and-japan-reflection-30th-year-anniversary

[6]. Jeffrey Frankel. (2015) The Plaza Accord, 30 Years Later, December, Working Paper 21813.

[7]. Kang, M. (2017) The Confidence Trap: Japan’s Past Bubble and China’s Recent Bubble. New Political Economy, 23(1), 1–26. doi:10.1080/13563467.2017.1321626

[8]. Dekle, R., & Hamada, K. (2015). Japanese monetary policy and international spillovers. Journal of International Money and Finance, 52, 175–199.

[9]. Yoshino, N., & Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. (2016) Causes and Remedies of the Japan’s Long-lasting Recession: Lessons for China. China & World Economy, 24(2), 23–47.

[10]. Roubini, N., & Sala-i-Martin, X. (1992). Financial repression and economic growth. Journal of Development Economics, 39(1), 5–30. doi:10.1016/0304-3878(92)90055-e.

[11]. Szirmai, A., & Verspagen, B. (2015). Manufacturing and economic growth in developing countries, 1950–2005. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 34, 46–59.

[12]. Lee, J.W., & McKibbin, W. J. (2018) Service sector productivity and economic growth in Asia. Economic Modelling. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2018.05.018.