1. Introduction

The importance and necessity of STEM Learning in Education (SLE) cannot be overstated in today's rapidly evolving global landscape. It has been highlighted by current educational theorists that the value of STEM Learning lies in fostering holistic development and preparing students for the dynamic challenges of the future [1]. Furthermore, it's recognized that SLE equips students with critical competencies like critical thinking, collaboration, and adaptability [2]. Another important aspect of SLE is the instillation of a lifelong learning habit, which can empower students for continuous personal and professional growth [3]. Consequently, SLE's importance as a fundamental element of modern education is widely recognized.

Despite its acknowledged importance, fostering motivation for SLE among students remains a significant challenge. Students' engagement and motivation towards STEM Learning are often lacking [4]. This pressing issue of maintaining consistent enthusiasm for SLE is often observed in many educational contexts [5]. There seems to be a disconnection between students' initial interest in SLE and their sustained commitment, a phenomenon that necessitates further examination [6]. Thus, motivating students towards SLE emerges as a critical concern. To tackle this problem, educational theorists and practitioners have turned their attention to gamification. The application of game mechanics in non-game contexts, or gamification, has been indicated to potentially enhance learning motivation [7]. It is posited that gamification can stimulate engagement, fostering an immersive and enjoyable learning experience [8]. The increasing implementation of gamification in various educational contexts, given its ability to engage and motivate learners, is also noted [9]. Therefore, gamification offers a promising solution to the motivation problem in SLE.

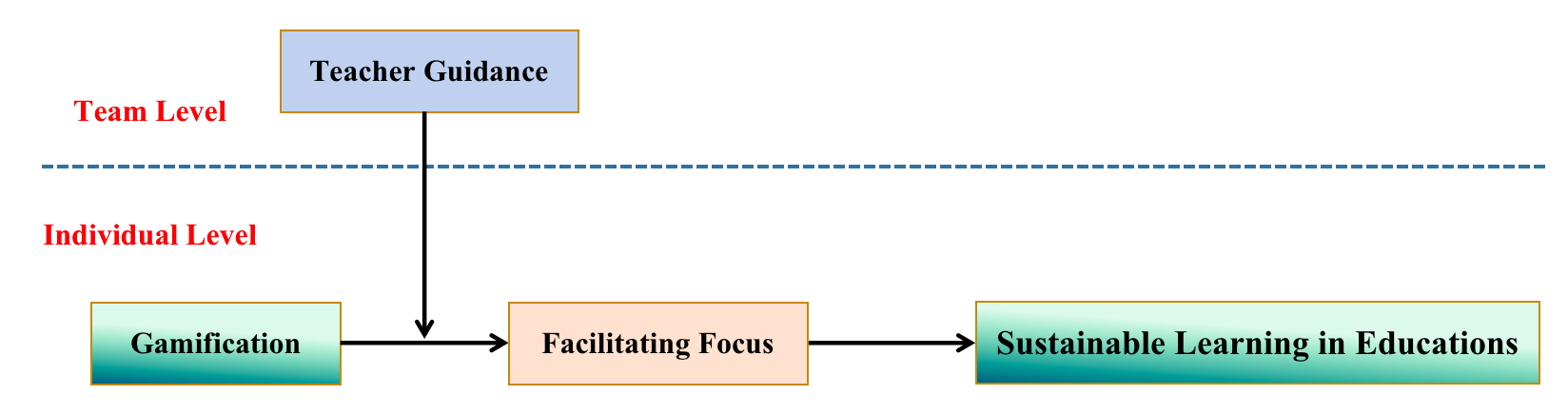

Therefore, this study embarks on a journey to elucidate the interplay of gamification, facilitating focus, and teacher guidance in enhancing SLE motivation. In light of the prevailing gaps in existing literature [4, 10], this study is poised to contribute new insights. The focus will be on the mediating role of facilitating focus and the potential moderating effect of teacher guidance in the relationship between gamification and SLE motivation. This examination holds significant implications for education stakeholders, potentially offering novel strategies for fostering SLE motivation.

2. literature review

2.1. The impact of gamification on students' STEM Learning in education

Gamification in education represents the use of game elements and mechanics in non-game contexts to foster learning and engagement. In essence, it embodies the employment of innovative pedagogical approaches to create immersive and interactive learning experiences [11]. It's been posited that gamification can improve motivation and performance among students, setting the ground for fostering STEM Learning in Education (SLE). SLE is rooted in long-term, integrative, and participative learning experiences that contribute to the individual and collective ability to enact sustainable development [12]. Herein, this research delves into the literature that underpins the influence of gamification on students' SLE.

The element of interactivity in gamification is conjectured to stimulate intrinsic motivation for STEM Learning. Interactivity characterizes gamification and cultivates an engaging environment for students to participate actively, promoting learning autonomy[13]. Studies have shown that such autonomy stimulates intrinsic motivation, which is crucial for continuous learning and investment in knowledge [14]. Thus, students participating in a gamified learning environment may not only demonstrate willingness but also display competence in STEM Learning due to their enhanced engagement.

Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1: Gamification has a positive impact on students' STEM Learning in Education.

2.2. The mediating role of facilitating focus

Facilitating focus in the educational context, akin to the promotion focus on the regulatory focus theory, refers to a learner's inclination towards growth, progress, and attainment of educational aspirations [15]. As a motivational construct, facilitating focus is likely to mediate the relationship between gamification (a pedagogical method fostering engaging and immersive learning experiences) and SLE (long-term, integrative, and participative learning towards sustainable development)[16].

Gamification encompasses game elements that cater to learners' aspirations and ambitions, thus instigating facilitating focus. Gamified learning environments often incorporate various levels of difficulty, rewards, and leaderboards, aiming not just at achieving a task but also at cultivating personal growth and mastery [17]. These environments foster learners' ideal self, directly stimulating their facilitating focus.

Gamification can foster a long-term orientation for learning, a central aspect of SLE. The progression mechanisms in gamified learning environments inspire learners to remain committed to their educational goals and stimulate their desire for continuous learning [18]. Thus, such a setting might keep learners engrossed in their academic growth and aspirations, facilitating a focused pursuit of long-term goals.

Gamification can encourage resilience in learning [19]. The challenge-based nature of gamified learning environments demands learners to persist in the face of difficulties, thereby cultivating resilience. This resilience, in turn, helps maintain a productive and sustained learning state, crucial for the pursuit of academic goals and aspirations [20]. Hence, gamification may enhance students' facilitating focus.

Moreover, facilitating focus can further foster SLE by enabling proactive behaviors in learning, improving the learning environment, and encouraging risk-taking [21]. Learners with a facilitating focus are driven by growth and development needs, tending to engage with educational challenges positively. Such focus also triggers learners to strive for improvement and perfection in their learning tasks, prompting them to proactively identify and address academic issues. Further, a higher facilitating focus may make learners more willing to embrace academic risks, necessary for self-directed learning exploration [22]. Thus, considering the potential influence of gamification on facilitating focus and SLE, it's plausible to posit that gamification might promote SLE through enhancing learners' facilitating focus. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2: Facilitating Focus plays a mediating role in the influence of Gamification on STEM Learning in Education.

2.3. Moderating effect of teacher guidance

As per the regulatory focus theory, the facilitating focus, drawn from learners' pursuit of ideal self, is closely associated with personal growth and self-actualization needs [23]. Teacher guidance, akin to transformational leadership in the workplace, can significantly influence students' growth and educational aspirations by providing direction, offering intellectual stimulation, and showing personalized care [24]. Consequently, in contexts where teacher guidance is pronounced, the impact of gamification on facilitating focus can be considerably enhanced [25].

Teacher guidance provides the developmental path for the practice of gamification. In the broader context, teachers guide students towards future developmental trajectories by defining an inclusive vision for learning. This instills a sense of direction, encouraging learners to perceive their learning journey as a career[26]. This guidance helps students navigate conflicts between short-term wins and long-term goals, ensuring they remain committed to their lifelong learning pursuits. Similarly, on a shorter timescale, teachers provide timely feedback on students' progress and areas of improvement, fostering the internalization of gamification's value pursuit of excellence[27]. Therefore, under effective teacher guidance, gamification can promote learners to pursue higher academic goals and integrate their commitment to learning quality into their self-concept. Thus, teacher guidance can create conditions for activating the benefits of gamification, enhancing the transformation of gamification into facilitating focus.

Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 3: Teacher guidance positively moderates the relationship between gamification and facilitating focus, that is, when teachers display a higher level of guidance, the positive impact of gamification on facilitating focus is stronger.

Hypothesis 4: Teacher guidance positively moderates the mediating effect of facilitating focus on the relationship between gamification and STEM Learning in Education (SLE), that is, when teachers display a higher level of guidance, the mediating effect of facilitating focus on the relationship between gamification and SLE is stronger.

In summary, based on the analysis, the following research model was constructed (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Research Model

3. METHOD

The research subjects of this study are drawn from the academic staff and students of two educational institutions in Jiangsu Province. These institutions mainly focus on advanced pedagogical methods and are known for employing gamification techniques in their curriculum, making them an ideal choice for studying the interaction between teacher guidance, gamification, and STEM Learning in Education (SLE) based on educational settings. After receiving consent from the administrations and academic departments of both institutions, to avoid the potential impact of common method bias, the research team distributed and collected the questionnaires at two different time points, with an interval of one month between each survey.

In the first survey round, students evaluated their engagement with gamification and their teacher's guidance style. Both teachers and students were asked to report their demographic information. In the second round, students assessed their own facilitating focus and perceived SLE, while teachers were asked to evaluate each student's level of academic engagement and achievement. Once the two rounds of surveys were complete, the data was matched using the unique codes provided on the questionnaires. A total of 85 teacher questionnaires and 430 student questionnaires were received. After excluding incomplete questionnaires and those from classes with fewer than 3 students, this study ended up with 75 valid teacher questionnaires and 385 valid student questionnaires. The effective response rate was approximately 83.2%. The effective sample had an average class size of 5.13 students. In terms of teacher samples, males represented 71.33%, and the 31-40 age group represented 67.45%. Regarding student samples, males accounted for 68.45%, with the 16-20 age group representing 54.05%.

4. Results

4.1. Common method bias and confirmatory factor analysis

Considering that this study's data were collected at two time points from multiple sources and that this research have maximized the research design with 12 variables, the first factor explanatory variable stands at 24.06%. Hence, there is no significant problem of common method bias in the data. Furthermore, this study employed confirmatory factor analysis to test the discriminant validity of the six factors included in the model, including Gamification Engagement, Teacher Guidance, Facilitative Focus, Defensive Focus, STEM Learning in Education (Self-report & Teacher Evaluation). The relevant results are presented in Table 1.

As observed in Table 1, compared to other alternative factor models, the original model best fits the data, although this research cannot entirely rule out the presence of common method bias in the data. To address this, the study first conducted a common method bias test on the data based on the Harman single factor method. Through exploratory factor analysis, this research found that the model provides the best causal effect when the characteristic root is greater than 1 (χ^2 = 596.165, df = 260, χ^2/df = 2.293, RMSEA = 0.056, CFI = 0.922, IFI = 0.924). This suggests that the variables have good discriminant validity and can undergo further analysis.

Table 1: Confirmatory factor analysis

Model | χ^2 | df | Δχ^2 (Δdf) | χ^2/df | RMSEA | CFI | IFI |

Original model (A, B, C, D, E, F) | 596.165 | 260 | - | 2.293 | 0.056 | 0.922 | 0.924 |

Five-factor model (A, B, C, D, E+F) | 1196.817 | 265 | 600.652 (5) *** | 4.516 | 0.093 | 0.785 | 0.788 |

Four-factor model (A, B, C+D, E+F) | 1268.977 | 269 | 672.812 (9) *** | 4.717 | 0.095 | 0.769 | 0.772 |

Three-factor model (A+B, C+D, E+F) | 1490.871 | 272 | 894.706 (12) *** | 5.481 | 0.105 | 0.719 | 0.722 |

Two-factor model (A+B+C+D, E+F) | 2381.294 | 274 | 1785.129 (14) *** | 8.691 | 0.137 | 0.514 | 0.520 |

Single factor model (A+B+C+D+E+F) | 2830.359 | 275 | 2234.194 (15) *** | 10.292 | 0.151 | 0.411 | 0.417 |

Note: A represents Gamification Engagement, B signifies Teacher Guidance, C refers to Facilitative Focus, D stands for Defensive Focus, E indicates STEM Learning in Education (Self-report), F means STEM Learning in Education (Teacher Evaluation), + signifies merger; *** means p<0.01.

4.2. Descriptive statistical analysis

In this research, SPSS22.0 statistical analysis software was utilized to examine the correlation of each variable. The mean, standard deviation, and correlation coefficient of each primary variable and control variable are detailed in Table 2. As indicated in Table 2, Gamification Engagement significantly positively correlates with Facilitative Focus (r=0.219, p<0.01), STEM Learning in Education (Self-report) (r=0.420, p<0.01), and STEM Learning in Education (Teacher Evaluation) (r=0.199, p<0.01), aligning with the direction of the pertinent hypothesis. Simultaneously, Defensive Focus correlates with Gamification Engagement (r=0.245, p<0.02) and Teacher Guidance (r=0.515, p<0.01), necessitating control for its influence.

Table 2: Mean, standard deviation and correlation coefficient

Category | Mean | Standard Deviation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

Team Variable | ||||||||

Teacher Gender | 1.239 | 0.428 | ||||||

Teacher Age | 3.676 | 0.526 | -0.094 | |||||

Team Size | 4.820 | 1.846 | -0.195 | 0.054 | ||||

Teacher Guidance | 4.020 | 0.233 | -0.161 | 0.111 | -0.172 | |||

Individual Variable | ||||||||

Student Gender | 1.280 | 0.452 | ||||||

Student Age | 2.781 | 0.701 | 0.039 | |||||

Gamification | 4.025 | 0.393 | -0.039 | -0.026 | ||||

Facilitative Focus | 3.987 | 0.533 | -0.042 | -0.048 | 0.219*** | |||

Defensive Focus | 4.040 | 0.586 | -0.031 | -0.013 | 0.245** | 0.515*** | ||

STEM Learning in Education (Self-report) | 3.993 | 0.490 | -0.011 | -0.059 | 0.420*** | 0.208**** | 0.164*** | |

STEM Learning in Education (Teacher Evaluation) | 3.775 | 0.652 | -0.260** | -0.074 | 0.199*** | 0.104* | 0.021 | 0.190**** |

4.3. Hypothesis testing

For this study, this research utilized Mplus7.0 software to create a multilevel linear model to test the main hypotheses. The pertinent results are shown in Table 3. From Models 3, it can be observed that the direct effect of gamification on STEM Learning in education is significant (γ=0.814, p<0.01), thus supporting Hypothesis 1.

Further, Table 3 shows that gamification has a significant positive impact on promotion focus (γ=0.345, p<0.01); promotion focus, in turn, has a positive impact on STEM Learning in education (γ=0.179, p<0.05). This research further utilized Mplus7.0 software to build a multilevel mediation model to test the mediation effect of promotion focus. The relevant results indicate that the effect of promotion focus between gamification and STEM Learning in education is significant (the effect value is 0.072, and the 95% CI is [0.002, 0.155]), thus confirming Hypothesis 2.

Table 3: Multilevel linear model regression results

Category | Facilitating Focus | Gamification | ||

Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

Team Variable | ||||

Teacher Gender | -0.006 (0.078) | 0.014 (0.075) | -0.025 (0.067) | -0.030 (0.064) |

Teacher Age | 0.136* (0.072) | 0.137* (0.075) | 0.082* (0.050) | 0.072 (0.050) |

Team Size | 0.003 (0.020) | 0.010 (0.019) | -0.011 (0.013) | -0.009 (0.013) |

Teacher Guidance | 0.253* (0.154) | 0.253* (0.154) | ||

Individual Variable | ||||

Student Gender | -0.020 (0.070) | 0.009 (0.069) | -0.009 (0.049) | 0.015 (0.054) |

Student Age | -0.017 (0.043) | -0.003 (0.041) | -0.057*(0.033) | -0.051 (0.038) |

Gamification | 0.345*** (0.106) | -3.592** (1.429) | 0.814*** (0.059) | |

Teacher Guidance×Gamification | 0.196** (0.090) | |||

Facilitative Focus | 0.179** (0.091) | |||

Defensive Focus | 0.026 (0.074) | |||

Intercept | 3.540*** (0.354) | 2.374*** (0.747) | 3.954*** (0.222) | 3.834*** (0.387) |

-2LL | 2812.834 | 2800.48 | 2637.686 | 3933.142 |

AIC | 2846.834 | 2840.481 | 2675.686 | 3993.142 |

BIC | 2912.075 | 2917.235 | 2748.603 | 4109.891 |

Next, this research analyzed the moderating role of teacher guidance between gamification and promotion focus. From Model 2 in Table 3, the interaction between teacher guidance and gamification is significant (γ=0.996, p<0.05). In order to represent the moderating effect of teacher guidance more intuitively, this study has included Figure 2. It can be seen from Figure 2 that when teacher guidance is high, gamification has a stronger positive effect on promotion focus (effect value 0.664, p<0.05); when teacher guidance is low, gamification has no significant effect on promotion focus (effect value 0.181, p>0.05). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is supported.

Figure 1: The moderating effect of teacher guidance

Finally, this study examined the moderating effect of teacher guidance on the first stage of the entire pathway based on a mediation model of cross-level moderation (refer to Table 4). From Table 4, the difference effect value between high and low teacher guidance is 0.099, and the 95% CI is [0.006, 0.191], indicating that teacher guidance significantly moderates the relationship between gamification and STEM Learning through promotion focus. When teacher guidance is high, the promotion focus induced by gamification positively affects STEM Learning (the effect value is 0.130, and the 95% CI is [0.074, 0.156]); when teacher guidance is low, the mediating effect of promotion focus is not significant (the effect value is 0.032, and the 95% CI is [-0.046, 0.110]). Therefore, Hypothesis 4 is supported.

Table 4: Cross-level Moderated Mediation Test Results

Category | First Stage | Second Stage | Two Stage | |||||

Point Estimate | 95% CI | Point Estimate | 95% CI | Point Estimate | 95% CI | |||

Path: Gamification→ Facilitating Focus → STEM Learning in Education (SLE) | ||||||||

High Teacher Guidance | 0.707*** | [0.455,0.959] | 0.184** | [0.024,0.344] | 0.130** | [0.074,0.156] | ||

Low Teacher Guidance | 0.173 | [-0.143,0.488] | 0.184** | [0.024,0.344] | 0.032 | [-0.046,0.110] | ||

High-Low Difference | 0.534*** | [0.154,0.914] | 0.099** | [0.006,0.191] | ||||

5. Discussion

The positive impact of gamification on STEM Learning indicates that learners experiencing gamified education will be more proactive in their learning and engage in continuous learning activities. This suggests that educational institutions and teachers can promote STEM Learning by implementing gamification in their teaching practices.

The pivotal role of teacher guidance in the effectiveness of gamification calls for teachers to balance the use of gamification and traditional teaching methods in their classrooms. Specifically, while teachers should create engaging and interactive learning environments through gamification, they should also provide clear guidance and support to their students, activating the role of gamification in promoting student learning and effectively enhancing student learning outcomes.

Educators should take appropriate measures to translate gamification into learners' positive learning motivation. This study suggests that gamification will positively affect learning behavior through the shaping of a positive learning motivation such as promotion focus. Therefore, teachers should not only focus on implementing gamification but also stimulate learners' motivation through effective measures.

6. Conclusion

Self-report and instructor assessment measures show that gamification improves STEM education. Gamification can help schools create a proactive and engaged learning environment. Gamification's positive link with facilitative focus shows its potential to create a conducive learning environment. Promotion focus is a key mediator between gamification and STEM Learning, supporting a positive association. This research suggests that educators should use gamification strategies and create a promotion-focused environment to maximise STEM learning.

The promotion focus-gamification relationship depends on a teacher's direction. Gamification improves promotion focus with strong teacher leadership, according to the study. This requires a balanced approach where teachers apply gamification tactics and provide clear direction and support to students to maximise STEM learning.

References

[1]. M. F. Zguir, S. Dubis, and M. Koç, "Embedding Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) and SDGs values in curriculum: A comparative review on Qatar, Singapore and New Zealand," Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 319, p. 128534, 2021.

[2]. A. Ben-Eliyahu, "Sustainable learning in education," Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 8, p. 4250, 2021, doi: 10.3390/su13084250.

[3]. K. Froehle, A. R. Phillips, and H. Murzi, "Lifelong learning is an ethical responsibility of professional engineers: Is school preparing young engineers for lifelong learning?," Journal of Civil Engineering Education, vol. 147, no. 3, p. 02521002, 2021.

[4]. L.-K. Ng and C.-K. Lo, "Flipped classroom and gamification approach: Its impact on performance and academic commitment on sustainable learning in education," Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 9, p. 5428, 2022.

[5]. S. W. Kozlowski and B. S. Bell, "Team learning, development, and adaptation," in Work group learning: Psychology Press, 2007, pp. 39-68.

[6]. C. Chapman, P. Armstrong, A. Harris, D. Muijs, D. Reynolds, and P. Sammons, School effectiveness and improvement research, policy and practice: Challenging the orthodoxy? Routledge, 2012.

[7]. R. W. M. Mee et al., "A Conceptual Model of Analogue Gamification to Enhance Learners' Motivation and Attitude," International Journal of Language Education, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 40-50, 2021.

[8]. A. Marougkas, C. Troussas, A. Krouska, and C. Sgouropoulou, "Virtual Reality in Education: A Review of Learning Theories, Approaches and Methodologies for the Last Decade," Electronics, vol. 12, no. 13, p. 2832, 2023.

[9]. S. Bennani, A. Maalel, and H. Ben Ghezala, "Adaptive gamification in E‐learning: A literature review and future challenges," Computer Applications in Engineering Education, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 628-642, 2022.

[10]. S. Bai, K. F. Hew, D. E. Gonda, B. Huang, and X. Liang, "Incorporating fantasy into gamification promotes student learning and quality of online interaction," International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 1-26, 2022.

[11]. K. W. Lau and P. Y. Lee, "The use of virtual reality for creating unusual environmental stimulation to motivate students to explore creative ideas," Interactive Learning Environments, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 3-18, 2015.

[12]. W. Scott and P. Vare, Learning, environment and sustainable development: A history of ideas. Routledge, 2020.

[13]. A. N. Saleem, N. M. Noori, and F. Ozdamli, "Gamification applications in E-learning: A literature review," Technology, Knowledge and Learning, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 139-159, 2022.

[14]. R. Kusurkar, T. J. Ten Cate, M. Van Asperen, and G. Croiset, "Motivation as an independent and a dependent variable in medical education: a review of the literature," Medical teacher, vol. 33, no. 5, pp. e242-e262, 2011.

[15]. M. Papi, A. V. Bondarenko, S. Mansouri, L. Feng, and C. Jiang, "Rethinking L2 motivation research: The 2× 2 model of L2 self-guides," Studies in Second Language Acquisition, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 337-361, 2019.

[16]. M. E. Sousa‐Vieira, J. C. López‐Ardao, M. Fernández‐Veiga, and R. F. Rodríguez‐Rubio, "Study of the impact of social learning and gamification methodologies on learning results in higher education," Computer Applications in Engineering Education, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 131-153, 2023.

[17]. C. Dichev, D. Dicheva, G. Angelova, and G. Agre, "From gamification to gameful design and gameful experience in learning," Cybernetics and information technologies, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 80-100, 2014.

[18]. D. Dicheva, K. Irwin, and C. Dichev, "Exploring learners experience of gamified practicing: For learning or for fun?," International Journal of Serious Games, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 5-21, 2019.

[19]. R. Kladchuen and J. Srisomphan, "The synthesis of a model of problem-based learning with the gamification concept to enhance the problem-solving skills for high vocational certificate," International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (Online), vol. 16, no. 14, p. 4, 2021.

[20]. S. E. Seibert, M. L. Kraimer, and P. A. Heslin, "Developing career resilience and adaptability," Organizational Dynamics, vol. 45, no. 3, pp. 245-257, 2016.

[21]. P. J. Collier and D. L. Morgan, "Community service through facilitating focus groups: The case for a methods-based service-learning course," Teaching Sociology, pp. 185-199, 2002.

[22]. S. Wilcox, "Fostering self-directed learning in the university setting," Studies in Higher Education, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 165-176, 1996.

[23]. R. Kark and D. Van Dijk, "Motivation to lead, motivation to follow: The role of the self-regulatory focus in leadership processes," Academy of management review, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 500-528, 2007.

[24]. A. Van Leeuwen and J. Janssen, "A systematic review of teacher guidance during collaborative learning in primary and secondary education," Educational Research Review, vol. 27, pp. 71-89, 2019.

[25]. A. C. M. Leung, R. Santhanam, R. C.-W. Kwok, and W. T. Yue, "Could gamification designs enhance online learning through personalization? Lessons from a field experiment," Information Systems Research, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 27-49, 2023. A. Bandura, "Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning," Educational psychologist, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 117-148, 1993.

[26]. A. Bandura, "Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning," Educational psychologist, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 117-148, 1993.

[27]. R. Costello, "Gamification Strategies for Retention, Motivation, and Engagement in Higher Education: Emerging Research and Opportunities: Emerging Research and Opportunities," 2020.

Cite this article

Su,W. (2024). Exploring the Impact of Gamification on STEM Learning in Education: The Mediating Role of Facilitating Focus. Communications in Humanities Research,40,179-188.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. M. F. Zguir, S. Dubis, and M. Koç, "Embedding Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) and SDGs values in curriculum: A comparative review on Qatar, Singapore and New Zealand," Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 319, p. 128534, 2021.

[2]. A. Ben-Eliyahu, "Sustainable learning in education," Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 8, p. 4250, 2021, doi: 10.3390/su13084250.

[3]. K. Froehle, A. R. Phillips, and H. Murzi, "Lifelong learning is an ethical responsibility of professional engineers: Is school preparing young engineers for lifelong learning?," Journal of Civil Engineering Education, vol. 147, no. 3, p. 02521002, 2021.

[4]. L.-K. Ng and C.-K. Lo, "Flipped classroom and gamification approach: Its impact on performance and academic commitment on sustainable learning in education," Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 9, p. 5428, 2022.

[5]. S. W. Kozlowski and B. S. Bell, "Team learning, development, and adaptation," in Work group learning: Psychology Press, 2007, pp. 39-68.

[6]. C. Chapman, P. Armstrong, A. Harris, D. Muijs, D. Reynolds, and P. Sammons, School effectiveness and improvement research, policy and practice: Challenging the orthodoxy? Routledge, 2012.

[7]. R. W. M. Mee et al., "A Conceptual Model of Analogue Gamification to Enhance Learners' Motivation and Attitude," International Journal of Language Education, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 40-50, 2021.

[8]. A. Marougkas, C. Troussas, A. Krouska, and C. Sgouropoulou, "Virtual Reality in Education: A Review of Learning Theories, Approaches and Methodologies for the Last Decade," Electronics, vol. 12, no. 13, p. 2832, 2023.

[9]. S. Bennani, A. Maalel, and H. Ben Ghezala, "Adaptive gamification in E‐learning: A literature review and future challenges," Computer Applications in Engineering Education, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 628-642, 2022.

[10]. S. Bai, K. F. Hew, D. E. Gonda, B. Huang, and X. Liang, "Incorporating fantasy into gamification promotes student learning and quality of online interaction," International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 1-26, 2022.

[11]. K. W. Lau and P. Y. Lee, "The use of virtual reality for creating unusual environmental stimulation to motivate students to explore creative ideas," Interactive Learning Environments, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 3-18, 2015.

[12]. W. Scott and P. Vare, Learning, environment and sustainable development: A history of ideas. Routledge, 2020.

[13]. A. N. Saleem, N. M. Noori, and F. Ozdamli, "Gamification applications in E-learning: A literature review," Technology, Knowledge and Learning, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 139-159, 2022.

[14]. R. Kusurkar, T. J. Ten Cate, M. Van Asperen, and G. Croiset, "Motivation as an independent and a dependent variable in medical education: a review of the literature," Medical teacher, vol. 33, no. 5, pp. e242-e262, 2011.

[15]. M. Papi, A. V. Bondarenko, S. Mansouri, L. Feng, and C. Jiang, "Rethinking L2 motivation research: The 2× 2 model of L2 self-guides," Studies in Second Language Acquisition, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 337-361, 2019.

[16]. M. E. Sousa‐Vieira, J. C. López‐Ardao, M. Fernández‐Veiga, and R. F. Rodríguez‐Rubio, "Study of the impact of social learning and gamification methodologies on learning results in higher education," Computer Applications in Engineering Education, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 131-153, 2023.

[17]. C. Dichev, D. Dicheva, G. Angelova, and G. Agre, "From gamification to gameful design and gameful experience in learning," Cybernetics and information technologies, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 80-100, 2014.

[18]. D. Dicheva, K. Irwin, and C. Dichev, "Exploring learners experience of gamified practicing: For learning or for fun?," International Journal of Serious Games, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 5-21, 2019.

[19]. R. Kladchuen and J. Srisomphan, "The synthesis of a model of problem-based learning with the gamification concept to enhance the problem-solving skills for high vocational certificate," International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (Online), vol. 16, no. 14, p. 4, 2021.

[20]. S. E. Seibert, M. L. Kraimer, and P. A. Heslin, "Developing career resilience and adaptability," Organizational Dynamics, vol. 45, no. 3, pp. 245-257, 2016.

[21]. P. J. Collier and D. L. Morgan, "Community service through facilitating focus groups: The case for a methods-based service-learning course," Teaching Sociology, pp. 185-199, 2002.

[22]. S. Wilcox, "Fostering self-directed learning in the university setting," Studies in Higher Education, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 165-176, 1996.

[23]. R. Kark and D. Van Dijk, "Motivation to lead, motivation to follow: The role of the self-regulatory focus in leadership processes," Academy of management review, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 500-528, 2007.

[24]. A. Van Leeuwen and J. Janssen, "A systematic review of teacher guidance during collaborative learning in primary and secondary education," Educational Research Review, vol. 27, pp. 71-89, 2019.

[25]. A. C. M. Leung, R. Santhanam, R. C.-W. Kwok, and W. T. Yue, "Could gamification designs enhance online learning through personalization? Lessons from a field experiment," Information Systems Research, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 27-49, 2023. A. Bandura, "Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning," Educational psychologist, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 117-148, 1993.

[26]. A. Bandura, "Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning," Educational psychologist, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 117-148, 1993.

[27]. R. Costello, "Gamification Strategies for Retention, Motivation, and Engagement in Higher Education: Emerging Research and Opportunities: Emerging Research and Opportunities," 2020.