1.Introduction

The Cantonese region, encompassing the Pearl River Delta, is situated at the convergence of the river and the sea. It enjoys a subtropical climate. Owing to the farming culture of the Central Plains and the distinctive natural geographical environment of Guangdong Province, the Worship of the Water deity holds exceptional significance for agricultural production and people's lives. The Northern Monarch, also known as "Zhen wu", is a typical Taoist water deity, and was introduced into the Cantonese region due to its functions related to water management, disaster prevention, and yang control. During the Ming-Qing Dynasties, the worship of the Northern Monarch gradually held an important position in the Cantonese region due to the recognition of the rulers, the efficacy of the Northern Monarch, and the developed material and economic foundation of the Cantonese region[1]. According to Reconstructing Renwei Temple inscription records, "Four miles west of Guangzhou city proper, there is a place near the South China Sea called Pantang, where a temple dedicated to Zhenwu had been constructed, and the villagers referred to it as Renwei Temple. It was established in the fourth year of Huangyou in the Song Dynasty (1052) and was reconstructed in the second year of Tianqi in the Ming Dynasty (1622).[2]" Renwei Temple, situated in Pantang Village, Longjin West Road, Liwan District, Guangzhou, is the earliest folk temple dedicated to the Northern Monarch constructed in the Cantonese region, featuring a distinct Lingnan traditional architectural style.

In addition to the construction of temples, people will also express their sincerity towards the deities through daily incense burning, prayer and special sacrificial activities[1]. Based on the research conducted on Daxiangguo Temple during the Tang-Song Dynasties, it is evident that the temple not only possesses a unique architectural structure but also encompasses a wide range of special rituals and activities [3]. It is believed that Renwei Temple represents a living heritage, as it not only consists of a static building ensemble but also incorporates dynamic sacrificial activities and the celebration of the Northern Monarch’s Birthday.

As a non-religious philosophical ideology, Confucianism possesses religious traits, such as the belief in destiny, humanism, and self-identification[4]. Hence, Confucianism has served as the cultural belief of traditional Chinese clan society for thousands of years and has exerted influences on all aspects of society. One instance of these influences is that in the site selection and layout of traditional buildings, ancient Chinese scholars employed the strategy of harmony between humans and nature, adaptation to local conditions and conformity to nature. Another instance is that in the planar form and facade form of traditional buildings, ancient Chinese scholars emphasized the concept of rank, the patriarchal clan system, the philosophy of "middle" and "harmony", etc.[5].

Renwei Temple is not merely a religious venue for worshippers to offer their devotions but also a public administrative organ of the village, jointly managed by each clan. Hence, it is not only of a religious nature but also of social and public significance; On one hand, Renwei Temple confirmed the Confucian belief in aspects such as site selection, layout, planar form, and decoration of the building. On the other hand, the rulers and clans enhanced the cohesion of the community and achieved control over the social groups through the ceremony of the Northern Monarch’s Birthday.

The temple serves as the material bearer of religious and Confucian cultural beliefs. On the one hand, the architectural space of Renwei Temple is influenced by folk beliefs. On the other hand, the rituals and activities centered on the architectural space of Renwei Temple have further enhanced the development of folk beliefs, thereby forming a close interactive relationship. This study conducts a case study of Renwei Temple in Canton and explores the interactive relationship between folk beliefs and temple architectural space in the Cantonese region through field investigation and data collection. The architectural space analyzed in this paper embodies the static site selection, layout, planar form, facade form characteristic, and dynamic sacrificial ceremony based on the building.

2.The architectural spatial characteristics of Renwei Temple

2.1.Site Selection and Layout

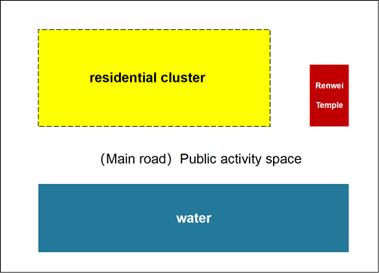

The site selection of Renwei Temple demonstrates the harmony and unity of architecture and the natural geographical environment[6]. According to figure 1 drawn by the author, its layout is organized in accordance with "water - square - temple", featuring the characteristic of central axis symmetry.

According to figure 2, Renwei Temple was constructed on sloping fields with bays on both the north and south sides, which has been redrawn by the author based on the Guangzhou City Road Map published by Guangzhou Public Service Bureau in 1947. It is situated at the border of the residential clusters of Pantang Village, in the front row of the building complex, and along the main-land and water transportation route of the village[7]. According to figure 3 taken by the author, there is a spacious public activity area in front of the temple. The building faces south and is symmetrical along its axis, featuring multiple courtyards.

Figure 1: The spatial layout pattern of Renwei Temple in Pantang village

Figure 2: Measuring the location map of Renwei Temple in the Song Dynasty

Figure 3: Square and Pond of Renwei Temple in Pantang Village

2.2.Planar Form

The planar form of Renwei Temple exhibits the characteristics of diverse types, distinct gradation and flexible combinations. The architectural form adheres to a regular pattern of fixed patterns and hierarchies, with the Middle Section buildings serving as the central axis. However, the spatial organizational form of the individual building is flexible and variable due to the varying needs of sacrificial ceremonies.

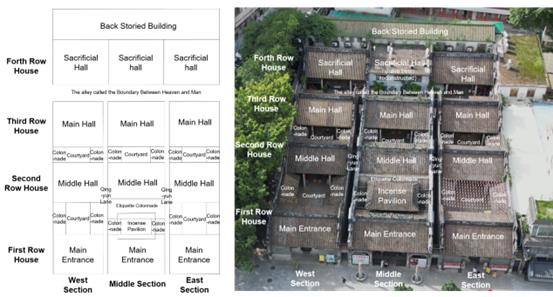

According to the table 1 created by the author, to meet people's demand for worshipping multiple deities, Renwei Temple was expanded from the original "One - Section - Three - Row house" temple in the Song Dynasty to the "Three - Section - Four - Row house" temple complex since the Ming-Qing Dynasties. According to figure 4 drawn by the author, its architectural elements encompass Main Entrances, Incense Pavilion, Etiquette Colonnade, Middle Halls, Main Halls, Sacrificial Halls, Back Storied Building, Colonnades, Courtyards, Qingyun Lanes, and an alley known as the Boundary Between Heaven and Man. Several crucial elements are as follows: Main Entrance, situated at the First Row House of the complex, serves as the official entrance of the temple and is splendidly adorned. Incense Pavilion, situated between the First and Second Row House in the Middle Section, is roofed and constitutes a space for incense burning and praying during sacrifices. Positioned between Middle Hall and Incense Pavilion, Etiquette Colonnade serves as a transitional corridor between interior and open space. Middle Hall is situated in the Second Row House of the complex and is integrated with the Colonnades and Main Entrance to constitute a courtyard, which is typically an indoor area for the installation of idols and the conduction of worship ceremonies. Main Hall is situated in the Third Row House and constitutes the core space of the complex, which was originally utilized for placing the Northern Monarch's statue and for worship.[8]

Figure 4: The planar form of Renwei Temple

Table 1: The planar form characteristics of Renwei Temple

Items |

Photograph |

Floor Plan |

Planar form characteristics |

Main Entrance |

|

|

Main Entrance in Middle Section adopts an open-column style and features a spacious porch area. The middle outer wall of Main Entrance in East and West Section is concave, creating a small corridor space. Three Main Entrances are partitioned into three rooms by beams and columns, encompassed by walls on three sides, and the rears are open towards Courtyard. |

Middle Hall |

|

|

The front of Middle Hall in Middle Section is opened towards Courtyard,, while a partition wall is placed at the rear The front and back of Middle Hall in East and West Section are opened towards Courtyards, and the space extends to Colonnades to form a unity. |

Main Hall |

|

|

Three Main Halls are encompassed by walls on three sides, with the front being open towards Courtyard. |

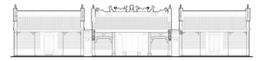

2.4.Facade form characteristic

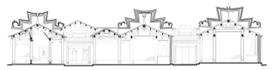

The facade form of Renwei Temple is characterized by a sense of progression and hierarchy. According to figure 5, the height and depth of the complex gradually expand to the north along the central axis, which is derived from the mapping data of cultural relics of Renwei Temple. The face width and decoration of the buildings in Middle Section are wider and more splendid than those in East and West Section. According to figure 6, the decoration of the three Main Entrances is relatively opulent and splendid, whereas that of the others is more succinct. Figure 6 is derived from the mapping data of cultural relics of Renwei Temple.

The buildings of Renwei Temple all feature Gable roofs, flanked by stepped gable walls, with exquisite components like wood carving, stone carving and brick carving. For instance, the main ridge of Main Entrances is adorned with pottery figures, pavilions and stage opera figures, and the fascia boards are carved with stories such as "Wu Song fighting the tiger", "Zhou Chu slaying the dragon", "Zhong Kui fighting ghosts", "Immortal guiding", "Fishing, firewood, plough, reading", etc. as well as other characters, auspicious animals, and auspicious plants.[9]

Figure 5: The profile chart of Middle Section of Renwei Temple

Figure 6: The facade form of Main Entrances

2.5.The Celebration of Northern Monarch’s Birthday centered around Incense Pavilion and the square in front of Renwei Temple

The celebrations of the Northern Monarch’s Birthday were presided over by the elders in the village, and were held in the Incense Pavilion and the square in front of Renwei Temple On the 3rd of the 3rd lunar month every year[10]. The intricate and elaborate rituals were designed to express gratitude to the deities for their blessings and to foster a sense of connection among the villagers.The main activities of the Northern Monarch’s Birthday consist of worship, feasting, Cantonese Opera Performances, and the statue parade of the Northern Monarch. Among them, the statue parade of Northern Monarch was the most important and influential activity.After people worshipped the statue of Northern Monarch in Incense Pavilion of Renwei Temple, a large number of people would carry the statue of Northern Monarch out. The parade route typically integrated the principal public spaces in the village, such as the square in front of RenWei Temple. The parade encompassed the village's most prestigious groups, along with traditional art performances like lion dancing and the Piaose parade.[11]

3.Research on the inner relation between folk beliefs and architectural spatial characteristics

The architectural space of Renwei Temple possesses the characteristics of harmony with nature, central axis symmetry, courtyard type, diverse types, distinct gradation, flexible combinations and strong cohesion. These features not only demonstrate the quintessence of the traditional architectural art in the Cantonese region but also are steeped in folk beliefs such as the Northern Monarch belief and Confucian cultural belief.

3.1.The Formation of the Order of the Relationship between God and Human occurred within the Belief System

Temple serves as the material carrier of religious belief. The concepts of Water Deity Worship and Taoism belief have exerted an influence on the evolution of temple architecture, and demonstrated the interaction of protection and respect between God and Humans in the construction of architectural space.

First of all, Renwei Temple is oriented southward and located adjacent to a river. It is not only influenced by Taoist feng shui, with an emphasis on the location principle of "Backed by mountains, surrounded by water, and surrounded by protective barriers" and adapting to nature, but also corresponds to the function related to water management of Northern Monarch. Secondly, its characteristics of axial symmetry, courtyard style, distinct gradation and space division emphasize the hierarchical sequence and the position of the main deity in the Middle Section. Thirdly, Renwei Temple is situated at the edge of the village's residential cluster and along the main road of land and water transportation in the village, embodying the integration of the village scope through the temple and the protection of the deity to the inhabitants. Finally, Renwei Temple separates the Incense Pavilion where people worship and the Middle Hall where the deity's statue is placed through the Etiquette Colonnade. This layout emphasizes the division of space between "deities" and "humans", meeting people's demand for deity worship and highlighting people's respect for the deities.[8]

3.2.Highlight the Confucian Culture of Ritual Thought

The traditional Confucian culture, centering on the ideology of the ritual system, exerted an influence on the construction of ancient Chinese architecture, and reflected the strict patriarchal hierarchy of the architectural space. It emphasized that the ancient architectural complex should be arranged in the courtyard style and symmetrically along the central axis, thereby forming a spatial order with distinct priorities.[12]

From the aspect of planar form, Renwei Temple is horizontally divided into three sections. The buildings of the Middle Section are situated on the central axis, taking the position of honor, while the East and West Section as the foils. The axis emphasizes the center and order, and the layout is harmonious. The complex comprises open courtyards, creating a pattern of external closure and internal openness, embodying the Confucian philosophy of "middle", "harmony" and "keep inside information from outsiders"[5].

From the aspect of spatial sequence, Renwei Temple consists of four row houses vertically. The height of the complex gradually ascends towards the north along the central axis, with the Main Halls located on the northern side as a mark of respect. This utilization of building orientation highlights the hierarchy of respect and priority, embodying the Confucian ritual order of "hierarchical"[13].

From the aspect of decoration, the facade of three Main Entrances is the most resplendent decorated place in the complex. The fascia boards are carved with myths, legends and historical stories such as "Zhou Chu slaying the dragon", "Fishing, firewood, plough, reading", etc[9].This emphasis on the construction of the exterior facade of the complex not only highlights the status and wealth of the builders, embodying the Confucian hierarchical notion of "contact between families of similar social status", but also reflects the characteristics of Confucianism's emphasis on "farming and reading" through the integration of local culture in architectural decoration[5].

From the aspect of form evolution, Renwei Temple, being a paradigm of the folk temple in the Cantonese region, despite its scale being smaller than that of the official temples, its architectural form is analogous to that of the large-scale official ritual architecture, which implies that there exists a connection between the official temple and the folk temple[8], both of which are influenced by the patriarchal concept of Confucianism.

3.3.A public space for integrating social groups

To effectively govern the people, the ancient rulers regarded temples as an important instrument for integrating diverse social groups such as clans and religious believers, and connected scattered public spaces through dynamic parade routes to facilitate the establishment and maintenance of social order.

On the one hand, Renwei Temple, serving as both a building for deity worship and a public administrative organ of the village, constitutes one of the crucial public spaces of the village.

The Incense Pavilion and the square in front of the temple enhance the entrance space, meeting the needs of villagers for activities such as worship and public gatherings.

On the other hand, the Northern Monarch's Birthday celebration of Renwei Temple integrates the main public spaces within the village, clarifies the scope of divine control, and enhances the integration of the village. The parade encompasses the most powerful group in the village, emphasizing the status of the village leaders. These activities fostered a sense of belonging and identification with the deities and clans among those involved, thereby enhancing village cohesion .[11]

4.Conclusion

The system and ideology of the ancient rulers restrained the development of society, however, society also contended with the value of the authorities through beliefs, thereby forming an interactive relationship[1]. Through the analysis and induction of the spatial characteristics and internal relations of temple architecture, this paper aims to enhance people's understanding and preservation of the cultural significance inherent in traditional temple architecture. This is instructive for the restoration of cultural relics, modern public cultural facilities and the construction of antique buildings.

From the perspective of cultural locality protection, temples, as the material carriers of folk beliefs, not only possess strong regional cultural characteristics, but also encompass a profound historical background. However, the restoration, construction and activities of the temples in the city are chaotic and are even gradually vanishing. The wisdom and aesthetics behind the traditional architectures of the ancestors have certain reference significance for the innovation and inheritance of contemporary temples and even public buildings in the Cantonese region.

From the perspective of holistic protection of heritage sites, the temple encompasses not merely the building itself but also the surrounding historical environment, including the square and water in front of the temple, other public spaces within the village, and so forth, as well as diverse rituals and activities held in the temple, such as the celebration of Northern Monarch's Birthday. The protection of heritage sites does not merely involve the independent safeguarding of the architectural appearance but also the conservation of its distinctive cultural landscape, historical ambience and cultural connotation beneath it.

From the perspective of social participation, traditional society integrated diverse people through ceremonies held in temples and squares, which is also worthy of reference for modern heritage protection. Architecture is never isolated from people and the environment. By means of the aggregation and openness of space and the organization of related cultural activities, diverse society groups can be guided to participate in the process of heritage protection, thereby truly realizing the dynamic inheritance of cultural heritage.

Of course, the wisdom underlying traditional architecture is diverse and inseparable from its historical background and the ideological system of the rulers. Therefore, the urban construction and planning initiatives for temple architecture should be viewed dialectically, which not only takes into consideration the inheritance of traditional culture and elements, but also establishes a modern development concept and innovates techniques in the contemporary context.

References

[1]. Zou Weidong. The interaction of the worship of "North Monarch" in Pearl River Delta and the social and economic development during the Ming-Qing Dynasties [D]. Jinan University,2001.https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=yQB21MkjwM8k_DTatcrge-jvKL1xCP7QBUVnIFHQx3_ChqvygpeTV3VQwk0njghcW5QGW4mCTT1TtquwYwhCxDXzXe48tFrE6xsFf3DBRpUKTbbutgEtwryHtB_tMlaUrXZH3RI99XfYWWxof3dsNDnc0TElSD1WKljwSF7DW5ROeK3I4Mnhnmkit0sBK_QQ09cWx-ThW5BZA2eQPevMQo1TboQCGnTv&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS

[2]. Compiled by Zheng Mengyu (Qing Dynasty) and Liang Shaoxian et al. The Annals of Nanhai County in Guangdong [M]. Guangzhou: Lingnan Fine Arts Publishing House,2007.

[3]. By Duan Yuming. Xiangguo Temple -- Between the sacred and the Common in Tang and Song Empires [M]. Chengdu Bashu Press,2004.

[4]. Written by Du Weiming, translated by Duan Dezhi. On the Religiosity of Confucianism: A Modern Interpretation of the Doctrine of the Mean [M]. 1999.

[5]. Qin Hongling. Qin, Hongling. (2007). Talking about the influence of Confucian culture on the construction of ancient Chinese capital cities. Huaxia Culture (04), 41-43. [J]. Huaxia Culture,2007.

[6]. Feng Zhifeng. Researching of traditional villages and houses of Guangzhou area basing on the cultural geography [D]. South China University of Technology,2014. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=yQB21MkjwM_8qSGNw_CESp0itBuH1jbums5Vo_lXe_IM3DBynIS2YxytDJMobRtErlyWM2U2MNDE5zkPUippA686a7jRNicubrX7TpXgB6FHPZHfZZQgT9Falzz4xroVazkunMeRV3gjbFqLKWt-R4-h-myOm4p4KtH5ySERGuIJPLzFjrPHqVEtpys63z2qsp2a3nbW4Yg=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS

[7]. Chen Jinpeng. Research on Spatial Morphology of Guangfu ancestral Halls in Panyu District, Guangzhou [D]. Guangzhou University,2021. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=yQB21MkjwM-l1p1oiQAzaYXzgx9PJ_bq0rHmjRBe0xX4EqvNdiu1rIGrCxELVK76xinDv_CWM8cn5EEGXFQCebLnZV1ekIJmBAgds2CBoTL6cUW1c-VGwtueSrOkSnSz5XpIf2Kq7JSkICBMy_LcS7igyAFxmhLeP-Gvk8OZImU7FWhBIUgzmxKY7X6494d9uCNX0iJheq4=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS

[8]. GU Xueping. Study on Cantonese Temples [D]. South China University of Technology,2017. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=yQB21MkjwM-HAj_nCurmtj8bV0CUeVJ3uBDf99grFeKvOZBATnAutiVXWgxKclQlWn2CEojUzHWv0zVrPvgmD3SCtvd34ScAMvouWW-o6t808gb_AzXrDuU2j6MswHqUqu3N4uxlqT71bOsHhBjEGAaTHBLQARKA8RRm2DExdaVor7Qaz_jYDveAaBVbOdku3jKYAePjmzU4dg691WDFgRHRIMqvZQVeqpiyACZST8c=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS

[9]. Chen Jianhua, Li Daxian, Guo Zeguo, Chen Jinbo, editor-in-chief. Guangzhou Cultural Relics Survey Compilation Liwan Volume [M]. Guangzhou: Guangzhou Publishing House.2006.

[10]. Wang Liang. Spiritual Response of Zen City: Ancestral Temple in Foshan and the Birth of the Northern Emperor [M]. Guangzhou: Guangdong Education Press,2013.

[11]. Luo Yixing, Xiao Haiming. Foshan Northern Emperor Culture and Society [M]. Guangzhou: Guangdong People's Publishing House,2017.

[12]. Huo Y. (2022). The wisdom of traditional Chinese architectural construction under the system of ethical order. Urban Architecture Space (04), 178-180.

[13]. Guo, C. C.. (2008). Confucianism in Beijing's Courtyard. Science and Technology Wind (05), 147+152. doi:10.19392/j.cnki.1671-7341.2008.05.133.

Cite this article

Zuo,H. (2024). Research on the Correlation Between Folk Beliefs and Temple Architectural Space: Case Study of Renwei Temple in Canton. Communications in Humanities Research,44,36-44.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Art, Design and Social Sciences

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Zou Weidong. The interaction of the worship of "North Monarch" in Pearl River Delta and the social and economic development during the Ming-Qing Dynasties [D]. Jinan University,2001.https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=yQB21MkjwM8k_DTatcrge-jvKL1xCP7QBUVnIFHQx3_ChqvygpeTV3VQwk0njghcW5QGW4mCTT1TtquwYwhCxDXzXe48tFrE6xsFf3DBRpUKTbbutgEtwryHtB_tMlaUrXZH3RI99XfYWWxof3dsNDnc0TElSD1WKljwSF7DW5ROeK3I4Mnhnmkit0sBK_QQ09cWx-ThW5BZA2eQPevMQo1TboQCGnTv&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS

[2]. Compiled by Zheng Mengyu (Qing Dynasty) and Liang Shaoxian et al. The Annals of Nanhai County in Guangdong [M]. Guangzhou: Lingnan Fine Arts Publishing House,2007.

[3]. By Duan Yuming. Xiangguo Temple -- Between the sacred and the Common in Tang and Song Empires [M]. Chengdu Bashu Press,2004.

[4]. Written by Du Weiming, translated by Duan Dezhi. On the Religiosity of Confucianism: A Modern Interpretation of the Doctrine of the Mean [M]. 1999.

[5]. Qin Hongling. Qin, Hongling. (2007). Talking about the influence of Confucian culture on the construction of ancient Chinese capital cities. Huaxia Culture (04), 41-43. [J]. Huaxia Culture,2007.

[6]. Feng Zhifeng. Researching of traditional villages and houses of Guangzhou area basing on the cultural geography [D]. South China University of Technology,2014. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=yQB21MkjwM_8qSGNw_CESp0itBuH1jbums5Vo_lXe_IM3DBynIS2YxytDJMobRtErlyWM2U2MNDE5zkPUippA686a7jRNicubrX7TpXgB6FHPZHfZZQgT9Falzz4xroVazkunMeRV3gjbFqLKWt-R4-h-myOm4p4KtH5ySERGuIJPLzFjrPHqVEtpys63z2qsp2a3nbW4Yg=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS

[7]. Chen Jinpeng. Research on Spatial Morphology of Guangfu ancestral Halls in Panyu District, Guangzhou [D]. Guangzhou University,2021. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=yQB21MkjwM-l1p1oiQAzaYXzgx9PJ_bq0rHmjRBe0xX4EqvNdiu1rIGrCxELVK76xinDv_CWM8cn5EEGXFQCebLnZV1ekIJmBAgds2CBoTL6cUW1c-VGwtueSrOkSnSz5XpIf2Kq7JSkICBMy_LcS7igyAFxmhLeP-Gvk8OZImU7FWhBIUgzmxKY7X6494d9uCNX0iJheq4=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS

[8]. GU Xueping. Study on Cantonese Temples [D]. South China University of Technology,2017. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=yQB21MkjwM-HAj_nCurmtj8bV0CUeVJ3uBDf99grFeKvOZBATnAutiVXWgxKclQlWn2CEojUzHWv0zVrPvgmD3SCtvd34ScAMvouWW-o6t808gb_AzXrDuU2j6MswHqUqu3N4uxlqT71bOsHhBjEGAaTHBLQARKA8RRm2DExdaVor7Qaz_jYDveAaBVbOdku3jKYAePjmzU4dg691WDFgRHRIMqvZQVeqpiyACZST8c=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS

[9]. Chen Jianhua, Li Daxian, Guo Zeguo, Chen Jinbo, editor-in-chief. Guangzhou Cultural Relics Survey Compilation Liwan Volume [M]. Guangzhou: Guangzhou Publishing House.2006.

[10]. Wang Liang. Spiritual Response of Zen City: Ancestral Temple in Foshan and the Birth of the Northern Emperor [M]. Guangzhou: Guangdong Education Press,2013.

[11]. Luo Yixing, Xiao Haiming. Foshan Northern Emperor Culture and Society [M]. Guangzhou: Guangdong People's Publishing House,2017.

[12]. Huo Y. (2022). The wisdom of traditional Chinese architectural construction under the system of ethical order. Urban Architecture Space (04), 178-180.

[13]. Guo, C. C.. (2008). Confucianism in Beijing's Courtyard. Science and Technology Wind (05), 147+152. doi:10.19392/j.cnki.1671-7341.2008.05.133.