Abstract: The These days, with the progress of women’s status, female athletes have played a more positive role in modern women sports, especially in women's participation in the Olympic Games. It is generally argued that the degree of women’s participation in Olympics Games denotes a sign of gender equality progress. Women do not only take their participation number and events in the Olympic Games as a measure of the gender progress in the field of sports but also tend to have a louder voice in decision-making. This article examines how the rising of women’s status gradually result in broader participation in Olympic Games by measuring the number of events and the distribution of medals among different countries for male and female competitions and the higher degree of women’s participation in IOC (International Olympic Committee). In fact, with the awakening awareness of gender equality, this research method can also employ in a wide range of fields in the future.

1. Introduction

The Olympic Games originated in ancient Greece over two thousand years ago and were named after cities. The first Olympic Games were held in 1896 and the first Winter Olympics in 1924. Now, the 32nd Olympic Games will be held in Tokyo in a few days. As the most influential sports event approaches, some researches on Olympic Games are carried out to study 120 years of Olympic Games history. And gender equality, which regards as one of the most crucial issues in the study of the Olympic Games, is worthwhile to make some research and study. Compared with the ancient Olympic Games, which rejected the participation of women, the modern Olympic Games followed the tradition of the ancient Olympic Games by explicitly prohibiting women from participating in any sports events. While the degree of women's participation in the Olympic Games is much greater today than ever before. Taking the Rio Olympic Games as an example, the amount of events for female athletes made up 47.4% of the total number of sports events and the percentage of women athletes has increased to 45%. Also, there are 34 countries that sent a larger number of female athletes than male athletes, even among them both in the Cook Islands and Liechtenstein that is such a small delegation, especially the Qatar and Saudi Arabia also unprecedentedly sent female players to attend the Olympic Games. And in terms of the medal’s distribution, female athletes won 969 medals, just a bit lower than medal counts of male athletes, which was at 1054. But, just taking women's participation number and events in the Olympic Games as a measure of the gender progress in the field of sports, would not be regarded as the sole criteria nowadays, we also need some more comprehensive measurement criteria in the future. Since the rise of the modern Olympic Games and the women, women’s participation in the Olympic Games has been endowed with the greater profound meanings of the sports, in other words, the degree of women’s participation gradually symbolizes the progress of gender equality. To some extent, this tendency leads to the tendency of pursuing equality with men in the development of women's participation in modern sports events. About 2500 years ago, Euripides, the famous ancient Greek dramatist, expressed his opinions through the words of a character in his play, said that "for girls - from Sparta, there with a young man in a very young woman clothed or naked race, and share with them the runway and wrestling with buildings".[3] According to this word, IOC should seek for more proper to achieve the goal of gender equality and encourage more women to attend the Olympic Games in a wide range of way rather than ask more female athletes to attend the competitions.

2. Literature Review

As everyone knew, in the beginning, the modern Olympic Games excluded women, the composer of the modern Olympics Pierre de Coubertin was a Frenchmen who was educated by the English gentleman education system, that emphasized the fact that Sports was a career without limit, for each person or profession, and the source of improvement both inner and outer. At the same time, however, he was opposed to women's participation in sport, influenced by the Darwinist theories popular among the European middle classes and his "aristocratic" background. [3] ‘The women's Olympic Games are inconvenient, uninteresting, unaesthetic and even incorrect,’ Coubertin declared at the 1912 Games in Stockholm and also said that ‘The true Olympic heroes are grown-ups. The Olympic Games must be limited to men and the women's primary role should be to crown the winners.’ [5] Although IOC had formally allowed women to participate in the Olympic Games at the Paris Meeting in 1924, Coubertin firmly hold his own opinion. At the 9th Olympic Games, Coubertin did not attend, but in his letter wrote: ‘I am still against women in the Olympics, although more and more female athletes have been allowed to compete, it's not my will’. At an important speech in 1935, Pierre de Coubertin said: ‘Although I am against women's participation in public places. But that doesn't mean they can't take part in all kinds of sports, just that they must not be the focus of public attention points. Women should wear laurels for the winners in the Olympic Games as they have in the past.’ [6] It was notable that at the end of the 19th century, over the period time that Pierre DE Coubertin spared his efforts to revive the modern Olympic Games, the development of women's sports had gradually created a new climate. Especially in the late 1870s, movement about gender equality in sports began to booms, such as some gender movements fighting for equal rights of sports in the United States, Britain, France, Germany, Denmark and Sweden and other countries. At that time, most of the existing sports, already had women take part in, also some women sports organizations held in those days, such as the French Women's Gymnastics Association, and the Women's Sports Association, which was established by Mrs Jo Vitale, the representative of the feminist movement in Germany. [7] In this condition, women's participation in the Olympic Games had become unstoppable, despite the strong opposition of Coubertin and others opponents.

Women have been competing in the Olympic Games since the second Paris Games in 1900. In Paris, there were two women's competitions, golf and tennis, that some women from Bohemia, France, Great Britain, Switzerland and the U.S.A participated in them. In 1908, women competed in archery, tennis, sailing and figure skating. in 1910, the Luxembourg Convention officially allowed women to compete in the Olympics, but the Games were suspended for eight years due to the First World War. in 1920, the International Olympic Committee in Antwerp meeting discussed the agenda for the forthcoming Olympic Congress. Once again, Coubertin expressed his opposition to women's participation in the Olympic Games. He proposed the abolition of all women's events. However, Clarie of France countered:- "Strong women will make mankind stronger and there are women who can already compete with men." Coubertin then asked if women should compete in the Olympics and the unanimous answer was "yes". By the time of the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics, women had entered the core athletic events of the Games. The entrance of women's sport and the Olympic Games was the result of the interaction between many factors that were at play in the trends of the times in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the most important driving force of which was the thriving feminist movement.

Although there were many women had attended in Olympic Games, the discussion of gender equality has officially been on the agenda of the IOC until 1991, when the IOC made it mandatory for any new sport seeking to participate in the Games to include women. 1995 saw the creation of the Women in Sport Commission, whose mandate was to promote equal opportunities for women to participate in and benefit from the practice of sport and physical activity. In addition, it intended to use sport as a tool to achieve gender equality and the empowerment of women. 1996 saw the final adoption of the Olympic Charter, which set out a commitment to gender equality. [1]

At the 2012 Summer Olympics in London, women's boxing was included in the competition program and women were eventually allowed to compete in all events. At the Sochi 2014 Winter Olympics, women represented 49% of the total and at the 2016 Summer Olympics, women represented 45%. [1]

Compared with the steadily increase number of female athletes, there are still have a lack of women members to participate in decision-making in Olympic Games. In 2015, women accounted for only 26% of the members of the IOC Executive Board, 19% of the National Olympic Committees and 14% of the International Federations. [1] This is not just a matter of numbers; it reflects the lack of women's perspectives in the decision-making process, so that women's interests are not properly protected and their experience and talents are not taken into account. Although there are many articles written by professionals about the participation of women in the Olympic Games and the development of women's status, this article will use graphic and artistic information to further argue that gender equality is a complex issue and the IOC still does not address its point of view.

3. Methodology

This article is based on a historical data set on www.kaggle.com, named ‘120 years of Olympic history: athletes and results’, [2] it contains the information of athletes and countries on the modern Olympic Games, including all the Games from Athens 1896 to Rio 2016. And the information and graphic in this article are gained from Tableau or www.olympic.org. This article mainly uses the function of drawing line chart and bar chart in the Tableau, based on the data set: ‘120 years of Olympic history: athletes and results’. [2]

4. Results

4.1. One of the symbols of gender equality--the expansion of women’s participation in the Olympic Games

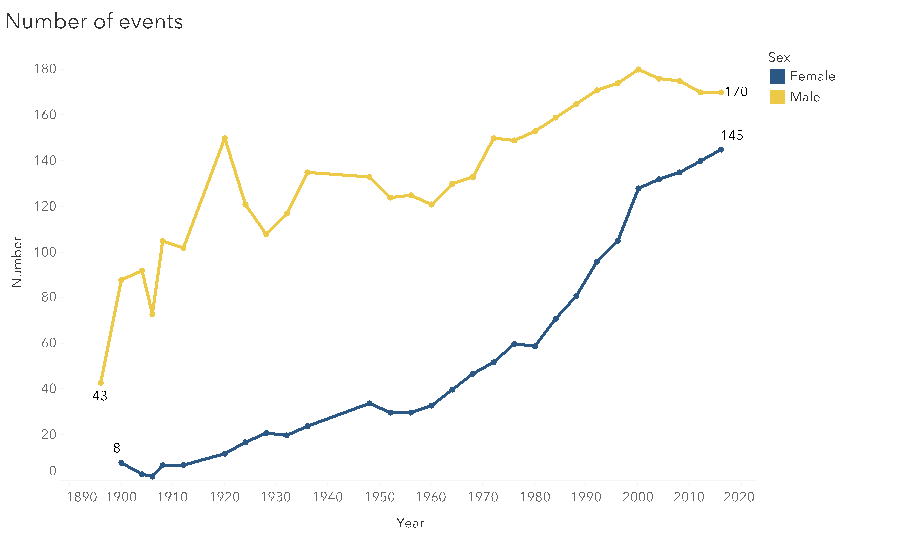

In 1928, women were admitted to participate in the core event of the Olympic Games, such as track and field athletics. Since then, the number and proportion of women athletes at the Olympic Games have increased and the competition events have been expanded. Especially in the 1970s, the proportion of both the number of events and the number of women’s participation in the Summer Olympic Games increased rapidly. By the 27th Sydney Olympic Games, women accounted for 42% of the 10,651 participants and women participated in 26 events among 28 major events, while in the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, there were 27 women's major events and 127 women's minor events, accounting for 42.1% of the total minor events. By the London Olympic Games in 2012, 140 of the 302 minor sports were contested by women, and it was amazing that the permission of women's participation in boxing. [3]

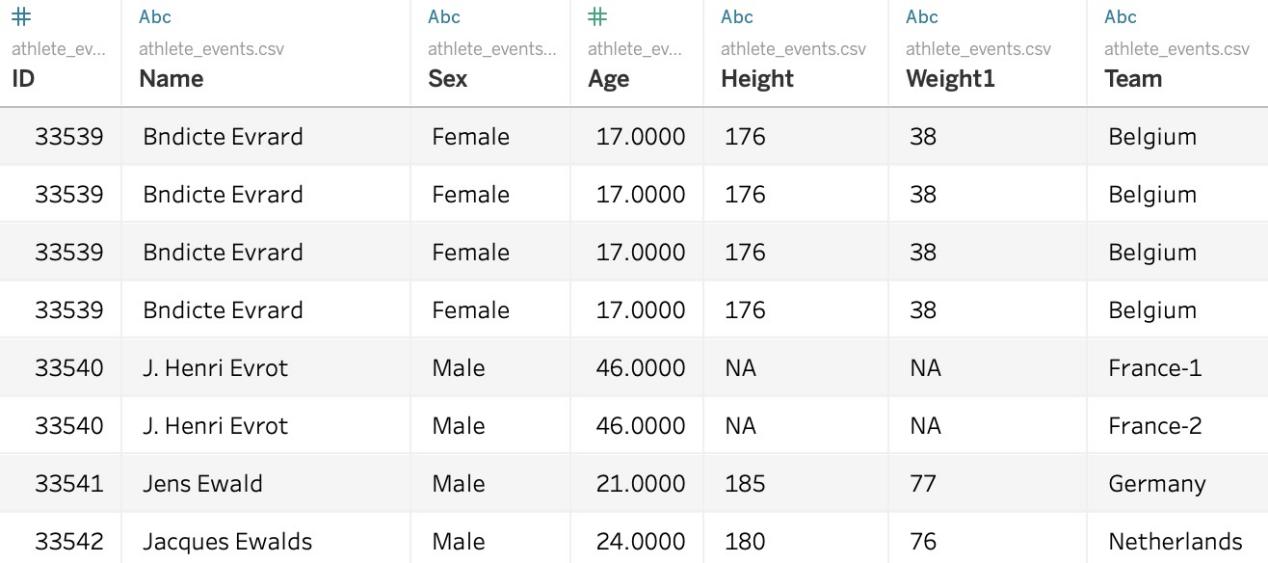

Table 1: A snapshot of the Olympics athletes information.

Figure 1: A Line chart illustrates the number of events over 120 years by sex in Summer Olympics.

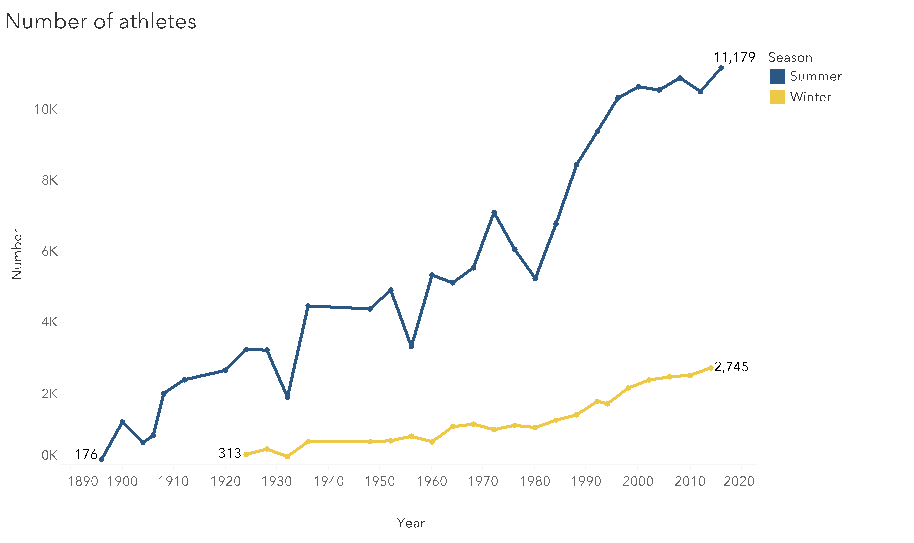

Figure 2: A line chart illustrates the number of athletes over 120 years.

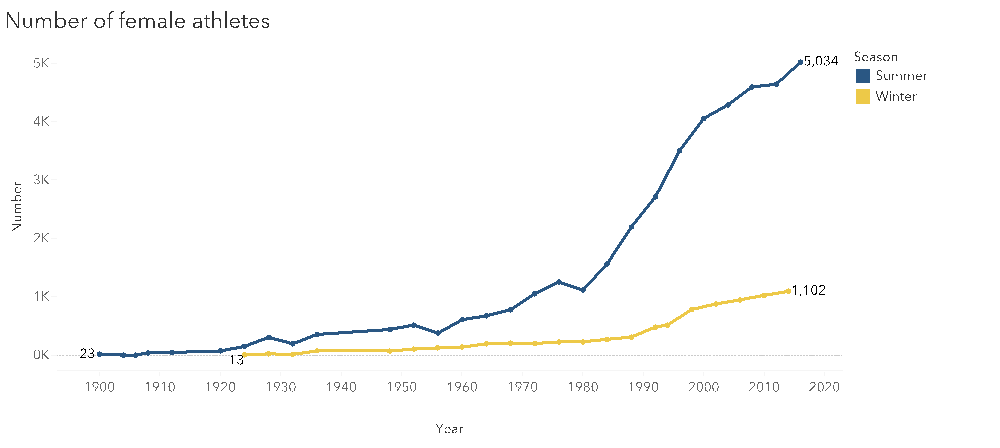

Figure 3: A line chart illustrates the number of female athletes over 120 years.

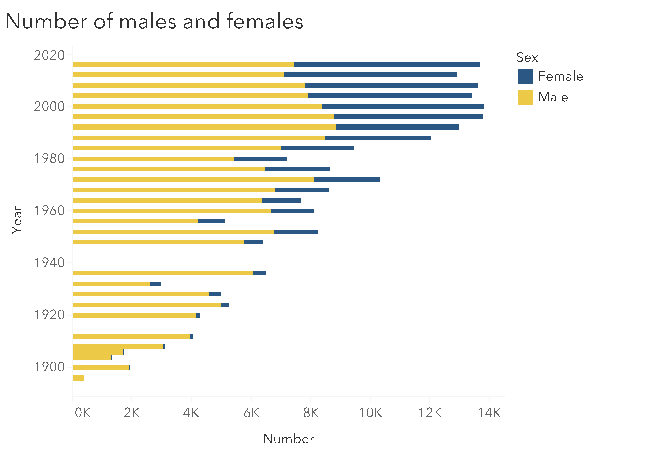

At the beginning of the Olympic Games, the difference in the proportion between male and female athletes was quite large, and the proportion of male athletes was always higher than that of female athletes. However, with the raising of gender equality, the proportion of female athletes has been increasing, especially from 1950s, the ratio of female to male athletes started to boom from 1:6 to now, almost 1:1.

It can be seen that in the 1st, 3rd and 5th Winter Olympic Games, one-third of the participating countries and regions sent women athletes, and in the remaining 10 Winter Olympic Games, more than half of the participating countries and regions sent women athletes. In terms of the number of participants, the total number of athletes doubled, from 258 in 1924 to 1,072 in 1980. The number of female athletes also grew rapidly, from 11 in 1924 to 232 in 1980, a nearly five-fold increase in the proportion of the total number of athletes. It can be seen that from 1924 to 1980, except for a few Winter Olympic Games, the number of women athletes from participating countries and regions gradually increased, and the proportion of women athletes in the total number of athletes also kept increasing. In terms of the number of participants and events, the participation of male and female athletes tends to be similar.

Figure 4: A bar chart compares the differences between female athletes and male athletes from 1896 to 2016.

4.2. The analysis of women’s participation in the IOC

4.2.1. The attitude of IOC chairman towards women participation in Olympic Games

Over the history of the Olympic Games, there were three chairmen, namely Samarach, Rogge and Bach whom all adopted the attitude of fully supporting women's participation in the Olympic Movement and actively promoted gender equality in the Olympic Movement. The following are their specific views: During his 21 years in office, Juan Antonio Samaranch not only introduced market mechanisms to pull the IOC out of its financial crisis, but he has also made the participation of women in the Olympic Games one of his top concerns. [8] At the end of 1990, Samaranch spoke at a working meeting of the International Sports Federation in Monte Carlo: "I am very proud to have women members of the IOC, but it is not enough. Women should play an important role in all areas of social life, not just in sports, so we will work harder," she said. In 1995, he initiated the formation of the IOC Commission on Women and Sport (formerly known as the Working Group on Women and Sport) and established the Women's Progress Section under the IOC Secretariat. From the time Samaranch took the helm of the IOC until her retirement in 2001, 17 women were elected to the committee, and three of them sat on the IOC's executive board, the highest echelon of the Olympic movement. They are Flol Isawa Fonseca (1990), Anita L. DeFranz (1993), and Gunilla Lindbergh (2001). [4]

And Rogge continued to promote gender equality in the Olympic Movement during his 12 years in office. He not only introduced women's boxing to the 2012 London Olympic Games but also made it historic to have women athletes from all participating countries at the 2012 London Olympics. Saudi Arabia has never sent a female athlete to the Olympics because of its religious views, but it did send two women to the 2012 Games in London, as did Qatar and Brunei, thanks to the tireless efforts of President Rogge. Although he made outstanding contributions to the equality of men and women in the Olympic Movement, Rogge did not criticize Coubertin's opposition to women's participation in the Olympic Games at the beginning of the modern Olympic Games but gave a great understanding. He is in the "Olympic declaration" said of Pierre DE Coubertin: “now more than 40% of the women's participation in sport, he will be surprised, because he has been against women, but we cannot, therefore, judge in the era of Pierre DE Coubertin, because in our age, there will be no entry barriers to women.” [9]

Thomas Bach has been in office for only two years, but he is credited with promoting gender equality. At the 127th Plenary Session in 2014, IOC members, led by Bach, formulated and unanimously adopted 40 recommendations of the Olympic Agenda 2020, among which the 11th recommendation is as follows: The IOC advocates gender equality and works with international sports federations to achieve a 50% female participation rate at the Olympic Games by creating more opportunities to participate in the Games and to encourage female participation in sport.[4] In addition, the IOC encourages mixed sports to be included in the Olympic Games. Thus, under Bach's leadership in the coming years, the aspiration for true gender equality in the Olympic movement will be further realized.

4.2.2. The development of women’s participation in IOC

The feminist movement in the world after the first wave, most countries have made women the right to vote, but over time, the feminists realized, if want to break the pattern of male social dominance, so women must enter the formal political institutions, increase in women deputies to the national and local government and the parliament in proportion. So they set about taking action to help more women enter formal political institutions in various ways. After a lot of fighting, the General Assembly passed a resolution in 1970 that women should be employed with equal opportunities in the United Nations Secretariat, followed by similar resolutions in 1972 and 1974. So, at the urging of the United Nations, the International Olympic Committee finally agreed to add women to its decision-making bodies.

Table 2: Female members of the IOC from 1985 to 2015

Time | The number of IOC members | The number of IOC female members | The proportion of female member in IOC |

1985 | 91 | 4 | 4.40% |

1995 | 106 | 7 | 6.60% |

2005 | 116 | 12 | 10.34% |

2015 | 132 | 21 | 15.91% |

data source : www.olympic.cn

In fact, since the founding of the International Olympic Committee, the world has always been dominated by men. Both Jean de Beaumont, an honorary member of the IOC, and Lord Killanen have tried, unsuccessfully, to get women on the board. As mentioned above, influenced by the world feminist movement and the United Nations, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) elected two women members at its 84th plenary session in 1981, namely Pi Hagemann and Ifonseka. Later, under the leadership of President Samaranch, Rogge and Thomas, the IOC actively included women members. In 1985, only four of the 91 IOC members, or 4.4 per cent, were women; In 1995, seven out of 106 members of the IOC were women, an increase in the proportion. In 2005, 12 of the IOC's 116 members, or 10.34 per cent, were women, an increase from the previous year but well below the IOC's target of 20 per cent. In 2015, of the 132 members of the IOC, 21 were women, accounting for 15.91 per cent. [10] It can be concluded that since 1981, the number of female members of the IOC has gradually increased, and the proportion of female members has gradually increased. However, compared with men, the position of female members in the decision-making level of the Olympic movement is still relatively low.

5. Conclusion

Now women have played an important role in the Olympic Games, and their position in the Olympic Games has been gradually established by the awaken of feminine consciousness and their competition with men.

Recently, there was a great development in women’s participation in the modern Olympic Games. However, the great achievements made by women in sports do not mean that women have become equal with men. There is still a great gap between men and women, for example, in the various sports institutions, women are very few in number and even fewer in leadership positions

There are not many women members in the IOC these days, but it is seen that more women have been attendance in the IOC. In 1981, the IOC only had two women added to its board. While by 2015, there were 21 female members, accounting for 15.91 per cent of the total number of IOC members. Although the figure was still less than the target set by the IOC itself, it is also a great achievement in the development of the modern Olympic Games and gender equality.

References

[1]. Alexandra Avena Koenigsberger. Gender equality in the Olympic Movement: not a simple question, not a simple answer[J]. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 2017, 44(3).

[2]. Rgriffin (2013). 120 years of Olympic history: athletes and results.Retrieved from https://www.kaggle.com/heesoo37/120-years-of-olympic-history-athletes-and-r.

[3]. Dou Hong-yin, Sun Shu-hui. Pursuit and Beyond Gender Equality: Women’s Participation in Modern Olympic Games(J). Journal of Beijing Sport University, 2015, 38(10): 37-42.

[4]. Liu Ning-juan. Historical Research on Women’s Participation in the Olympic Movement from the Perspective of Feminist Movement(D). Capital University of Physical Education And Sports, 2016.

[5]. Sylvain Ferez. From women’s Exclusion to Gender Institution:A Brief History of the Sexual Categorisation Process within Sport[J]. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 2012, 29(2): 272-285.

[6]. Yves-pierre Boulongne, Karl Lennartz. The International Olympic Committee-One Hundred Years The Idea-The Presidents-The Achievements Volume I[M]. Lausanne :The International Olympic Committee , 1994, 197.

[7]. Fan Hong. On the Movement of Women Striving for the Equality of Sports Rights in Modern West(J). Sports Culture Guide, 1989(2): 69-75.

[8]. Juan Antonio Samaranch. Memorias Olimpicas(M).World Culture Publishing House, 2003, 80.

[9]. Le baron Pierre De Coubertin. Olympic Manifesto(M).People's Publishing House, 2008, 130.

Cite this article

Zheng,S. (2021). The Development of Women’s Status in the Olympic Games. Communications in Humanities Research,1,28-35.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Educational Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries (ICEIPI 2021), Part 2

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Alexandra Avena Koenigsberger. Gender equality in the Olympic Movement: not a simple question, not a simple answer[J]. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 2017, 44(3).

[2]. Rgriffin (2013). 120 years of Olympic history: athletes and results.Retrieved from https://www.kaggle.com/heesoo37/120-years-of-olympic-history-athletes-and-r.

[3]. Dou Hong-yin, Sun Shu-hui. Pursuit and Beyond Gender Equality: Women’s Participation in Modern Olympic Games(J). Journal of Beijing Sport University, 2015, 38(10): 37-42.

[4]. Liu Ning-juan. Historical Research on Women’s Participation in the Olympic Movement from the Perspective of Feminist Movement(D). Capital University of Physical Education And Sports, 2016.

[5]. Sylvain Ferez. From women’s Exclusion to Gender Institution:A Brief History of the Sexual Categorisation Process within Sport[J]. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 2012, 29(2): 272-285.

[6]. Yves-pierre Boulongne, Karl Lennartz. The International Olympic Committee-One Hundred Years The Idea-The Presidents-The Achievements Volume I[M]. Lausanne :The International Olympic Committee , 1994, 197.

[7]. Fan Hong. On the Movement of Women Striving for the Equality of Sports Rights in Modern West(J). Sports Culture Guide, 1989(2): 69-75.

[8]. Juan Antonio Samaranch. Memorias Olimpicas(M).World Culture Publishing House, 2003, 80.

[9]. Le baron Pierre De Coubertin. Olympic Manifesto(M).People's Publishing House, 2008, 130.