1. Introduction

With the rapid acceleration of globalization, English has grown increasingly essential as the primary language for international communication. However, non-finite verbs present a persistent challenge for English learners due to their diverse forms and complex usage [1]. Research by Tang highlights that Chinese students, influenced by the linguistic differences between Chinese and English finite and non-finite verb forms, experience notable cross-linguistic effects when acquiring English non-finite verbs [2]. Traditional teaching approaches, which generally rely on in-class explanations and written exercises, often lack the personalized guidance and interactivity needed to effectively meet the diverse needs of individual learners [1].

Recently, advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) have introduced new possibilities for the field of education. By analyzing learners’ behavioral patterns and feedback, AI can deliver personalized learning recommendations and tailored instructional content, substantially enhancing learning outcomes and experiences [3]. Specifically, in grammar instruction, AI tools like ChatGPT offer interactive language environments that approximate real-life language application, proving especially beneficial in exam-focused educational contexts [4].

This study seeks to examine the practical efficacy of ChatGPT in teaching non-finite verbs, focusing on its role in enhancing grammatical accuracy and retention among second language learners. The study recruited sixty college-level EFL learners, with an average age of 20, divided into two groups of 30 participants each [3,4]. The experimental group engaged with personalized learning via ChatGPT, while the control group received traditional instruction. This research aspires to furnish educators with a practical framework for leveraging AI tools in language education, while also providing a theoretical foundation for future instructional methodologies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Role of AI in Language Education

ChatGPT, as a groundbreaking technology, has shown significant potential in educational contexts. Research indicates that ChatGPT enriches learners’ experiences by delivering customized content tailored to varying language abilities, topics, and proficiency levels [3]. Moreover, its ability to provide immediate feedback and personalized guidance supports learners in improving both their linguistic accuracy and organizational skills in writing [5].

2.2. Difficulties in Acquiring Non-Finite Verbs

Non-finite verbs present challenges to learners due to their diverse forms and intricate applications [1]. A study by Zhan on Chinese EFL learners’ topic-based writing highlights frequent errors in non-finite verb usage, suggesting that these students face considerable difficulties in mastering such grammatical structures [6]. Traditional instructional methods often fall short in effectively addressing these issues, leaving learners struggling with practical application. Incorporating AI tools like ChatGPT enables learners to experience more personalized and interactive instruction, which has been shown to significantly enhance learning outcomes [3,4].

2.3. Balancing Dependency and Skill Development

Despite ChatGPT’s demonstrated potential to improve language acquisition, there is a concern that reliance on this tool may lead some learners to depend excessively on AI feedback, potentially hindering the development of creativity and critical thinking skills, which are essential to writing instruction [7]. Therefore, educators should approach ChatGPT as a supplementary tool to enhance, rather than replace, traditional instruction, exploring strategies for effective integration into teaching practices [7].

ChatGPT, as an innovative technology, has demonstrated significant potential in the educational field. Studies indicate that ChatGPT enriches the learning experience by providing customized content tailored to varying language proficiencies, topics, and levels [3]. Moreover, its capacity to deliver immediate feedback and personalized guidance supports learners in enhancing both linguistic and organizational skills in writing [5].

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

Sixty sophomore EFL students with an average age of 20 were recruited for this study, with equal numbers allocated to an experimental group and a control group. All participants had intermediate English proficiency, ensuring that they could engage effectively with the study content and tasks.

Participants were recruited through campus announcements, WeChat group postings, and email invitations. Initially, interested students filled out a background survey covering English proficiency, learning motivation, willingness to participate, and prior coursework. Based on these surveys, the research team selected students with a clear need to enhance grammatical skills and a willingness to commit time to the study. Selected students completed an English proficiency test to confirm their intermediate level, ensuring they could understand and participate fully in the study’s tasks.

Sophomores were chosen because they had completed foundational English courses and, at this stage, face a growing need for complex grammatical structures. This selection ensured that the study provided meaningful data on the potential benefits of non-finite verb instruction.

3.2. Experimental Design

3.2.1. Selection of Non-Finite Verbs

Fifteen high-frequency verbs and their non-finite forms, drawn from the CET-4 vocabulary list, were selected for instruction (Table 1). These verbs covered infinitives, gerunds, and both present and past participles.

Table 1: Verbs and Their Non-Finite Forms

(Verb) | (Gerund) | (Infinitive) | (Past Participle) | (Present Participle) |

achieve | achieving | to achieve | achieved | achieving |

apply | applying | to apply | applied | applying |

assess | assessing | to assess | assessed | assessing |

choose | choosing | to choose | chosen | choosing |

communicate | communicating | to communicate | communicated | communicating |

contribute | contributing | to contribute | contributed | contributing |

develop | developing | to develop | developed | developing |

enhance | enhancing | to enhance | enhanced | enhancing |

establish | establishing | to establish | established | establishing |

influence | influencing | to influence | influenced | influencing |

maintain | maintaining | to maintain | maintained | maintaining |

participate | participating | to participate | participated | participating |

recommend | recommending | to recommend | recommended | recommending |

require | requiring | to require | required | requiring |

support | supporting | to support | supported | supporting |

3.2.2. Duration and Instructional Methods

Both groups engaged in a six-week course, meeting three times weekly for 60-minute sessions.

The experimental group utilized ChatGPT for personalized learning, completing exercises under AI guidance with instant feedback. For instance, ChatGPT provided structured exercises for “to apply” and corrected errors. The control group used traditional methods, with teacher-led grammar explanations and exercises from textbooks. Teachers introduced correct usage examples and guided students through exercises.

3.2.3. Testing

Pre-test: An initial grammar test evaluated learners’ baseline understanding of non-finite verbs, designed with CET-4 content covering multiple-choice, fill-in-the-blank, and translation items.

Post-test: The post-test, similar to the pre-test, measured learners’ progress with identical question types, ensuring comparability.

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

3.3.1. Data Collection

Quantitative data included pre- and post-test scores, with qualitative data from questionnaires and interviews assessing learners’ experiences with ChatGPT, such as motivation and satisfaction.

3.3.2. Data Analysis

Quantitative Analysis: T-tests on pre- and post-test scores using SPSS evaluated differences between groups, assessing ChatGPT’s impact on learning outcomes.

Qualitative Analysis: Thematic analysis of questionnaire and interview data identified common feedback and suggestions, such as perceived benefits of ChatGPT feedback.

3.4. Evaluation Criteria

Accuracy: Measured by score improvements from pre- to post-tests.

Motivation: Changes in motivation, assessed through surveys.

User Experience: Learner feedback on ChatGPT’s usability and effectiveness.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Test Results

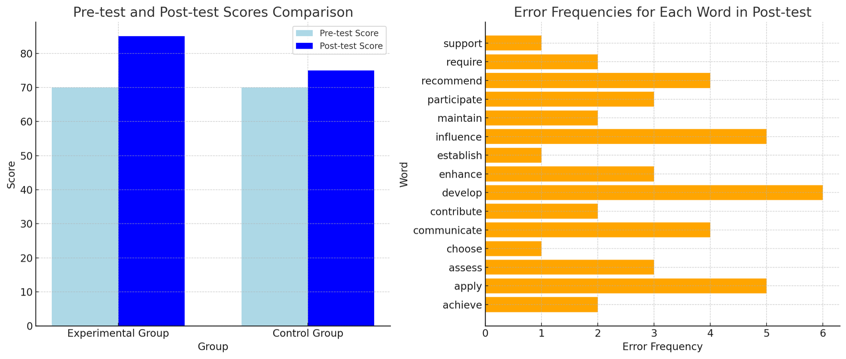

After six weeks of instructional intervention, post-tests were administered to both the experimental and control groups to assess their progress in mastering non-finite verbs. Statistical analysis, as illustrated in Figure 1, reveals that the experimental group achieved significantly higher average scores in the post-test compared to the control group, suggesting that personalized learning facilitated by ChatGPT contributed to notable improvements in grammatical accuracy.

Experimental Group: The average score of the experimental group increased by 15 points from the pre-test, reaching an average of 85.

Control Group: The control group recorded an average increase of 5 points in the post-test, reaching an average score of 75.

Furthermore, the experimental group participants generally reported higher levels of motivation and satisfaction in post-study questionnaires, underscoring ChatGPT’s potential to enhance the learning experience [8, 9].

Figure 1: Comparison of Pre-test and Post-test Scores and Error Frequency for Each Word in the Post-test

4.2. Discussion

The results of the experiment, as demonstrated in Figure 1, show that the experimental group using ChatGPT for non-finite verb instruction exhibited greater improvements in both grammatical accuracy and engagement than the control group. This outcome supports the use of ChatGPT as a transformative tool in educational settings [1,3].

4.2.1. Benefits of Personalized Learning and Immediate Feedback

ChatGPT’s capacity to deliver a personalized learning experience with instant feedback stands out as a key advantage. By analyzing learner input, ChatGPT promptly corrected errors and provided tailored suggestions, yielding a marked effect in this study [4]. Students in the experimental group frequently reported receiving more targeted guidance, which reduced misunderstandings related to grammatical rules [2,4]. For example, learners were exposed to diverse sentence structures and received immediate corrective feedback during practice sessions, consistent with findings by Huang et al. that AI tools in language education offer varied learning pathways and immediate corrections [3].

4.2.2. Enhancing Learning Motivation

The experimental group showed increased motivation, likely due to ChatGPT’s interactive and novel features. Research indicates that AI interactions can help maintain learner engagement and foster positive attitudes, aligning with Barrot’s assertion that AI tools can increase motivation through enhanced engagement and interactivity [5].

4.2.3. Balancing Dependency and Fostering Critical Thinking

Despite the positive results, caution is warranted regarding potential learner dependency on ChatGPT. Excessive reliance on AI feedback may hinder the development of autonomous learning and critical thinking skills, which are fundamental to effective writing instruction [7]. Tseng and Warschauer emphasize the importance of balancing AI use with strategies that cultivate students’ independent learning skills [7].

5. Conclusion

This study examined the comparative effectiveness of ChatGPT versus traditional instruction in teaching non-finite verbs, highlighting the potential of AI tools to enhance language learning outcomes. Findings indicate that learners who used ChatGPT outperformed those in traditional instruction in both grammatical accuracy and motivation, providing empirical evidence for the integration of ChatGPT in second language teaching and suggesting implications for future instructional practices.

AI tools enable personalized learning experiences that substantially improve learning outcomes, allowing educators to supplement classroom instruction with ChatGPT to support students’ independent study and practice outside class [4,5]. Furthermore, incorporating AI technology can boost student motivation and engagement; thus, educators are encouraged to integrate it into classroom activities to foster a more interactive and engaging learning environment [5]. However, teachers should ensure that students develop autonomous learning skills, avoiding excessive reliance on AI feedback. This goal can be supported by incorporating open-ended questions and critical thinking exercises [7,10].

While this study yielded promising results, it also had limitations. For example, the study sample comprised college students at an intermediate English level, meaning the results may not be generalizable to learners of other proficiency levels or age groups. Additionally, the study duration was relatively short, limiting the assessment of long-term effects of AI tools on learning outcomes. Future research should consider a larger, more diverse sample and extend the duration of the study to achieve more comprehensive insights. Investigating the application and effectiveness of AI tools across varied language learning contexts will also be a valuable direction for future inquiry. This study provides a foundational framework for educators to effectively incorporate AI tools in language teaching and encourages further empirical research to expand the use of AI technology in educational settings.

References

[1]. Han, Z. (2024). ChatGPT in and for second language acquisition: A call for systematic research. [J] Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 46, 301-306.

[2]. Huang, W., Hew, K. F., & Fryer, L. K. (2022). Chatbots for language learning—Are they really useful? A systematic review of chatbot-supported language learning. [J] Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38, 237-257.

[3]. Xiao, F., Zhao, P., Sha, H., Yang, D., & Warschauer, M. (2023). Conversational agents in language learning. [J] Journal of China Computer-Assisted Language Learning.

[4]. Barrot, J. S. (2023). Using ChatGPT for second language writing: Pitfalls and potentials. Assessing Writing, 57, 100745.

[5]. Tseng, W., & Warschauer, M. (2023). AI-writing tools in education: If you can't beat them, join them. [J] Journal of China Computer-Assisted Language Learning, 3(2), 258-262.

[6]. Tang, M. (2020). Crosslinguistic influence on Chinese EFL learners' acquisition of English finite and non-finite distinctions. Cogent Education, 7(1), 1721642. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2020.1721642

[7]. Han, F. (2013). Pronunciation problems of Chinese learners of English. ORTESOL Journal, 30, 26-30.

[8]. Zhan, H. (2015). Frequent errors in Chinese EFL learners' topic-based writings. English Language Teaching, 8(5), 72-81. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v8n5p72

[9]. Zindela, N. (2023). Comparing Measures of Syntactic and Lexical Complexity in Artificial Intelligence and L2 Human-Generated Argumentative Essays. International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology (IJEDICT), 19(3), 50-68.

[10]. Rudnicka, K. (2023). Can Grammarly and ChatGPT accelerate language change? AI-powered technologies and their impact on the English language: Wordiness vs. conciseness. Procesamiento del Lenguaje Natural, 71, 205-214.

Cite this article

Gao,X. (2024). The Impact of AI on the Accuracy of Second Language Learners in Acquiring Non-Finite Verb Structures. Communications in Humanities Research,61,1-6.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Literature, Language, and Culture Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Han, Z. (2024). ChatGPT in and for second language acquisition: A call for systematic research. [J] Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 46, 301-306.

[2]. Huang, W., Hew, K. F., & Fryer, L. K. (2022). Chatbots for language learning—Are they really useful? A systematic review of chatbot-supported language learning. [J] Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38, 237-257.

[3]. Xiao, F., Zhao, P., Sha, H., Yang, D., & Warschauer, M. (2023). Conversational agents in language learning. [J] Journal of China Computer-Assisted Language Learning.

[4]. Barrot, J. S. (2023). Using ChatGPT for second language writing: Pitfalls and potentials. Assessing Writing, 57, 100745.

[5]. Tseng, W., & Warschauer, M. (2023). AI-writing tools in education: If you can't beat them, join them. [J] Journal of China Computer-Assisted Language Learning, 3(2), 258-262.

[6]. Tang, M. (2020). Crosslinguistic influence on Chinese EFL learners' acquisition of English finite and non-finite distinctions. Cogent Education, 7(1), 1721642. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2020.1721642

[7]. Han, F. (2013). Pronunciation problems of Chinese learners of English. ORTESOL Journal, 30, 26-30.

[8]. Zhan, H. (2015). Frequent errors in Chinese EFL learners' topic-based writings. English Language Teaching, 8(5), 72-81. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v8n5p72

[9]. Zindela, N. (2023). Comparing Measures of Syntactic and Lexical Complexity in Artificial Intelligence and L2 Human-Generated Argumentative Essays. International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology (IJEDICT), 19(3), 50-68.

[10]. Rudnicka, K. (2023). Can Grammarly and ChatGPT accelerate language change? AI-powered technologies and their impact on the English language: Wordiness vs. conciseness. Procesamiento del Lenguaje Natural, 71, 205-214.