1. Introduction

Throughout her life, Alice Neel (1900-1984) has been ascribed a multitude of labels: from an artist, outcast, mother to a radical, communist, feminist, anti-feminist and many more. Through the ebb and flow of time, the roulette of labels assigned to describe her changed as well. In retrospect, looking through accounts of people who interacted with Neel, her art, quotes, each of these labels had relevance for different times in her life.

Her portraits, consisting of an eclectic array of personalities, ranging from Andy Warhol to New York mayor Ed Koch, feminist writer Adrienne Rich, or simply a person she stumbled upon on the street. Ann Sutherland Harris, a feminist art critic, described Neel’s collection of work to serve as “a kind of diary” for the people, experiences and instances in her life and in a review of a 1994 exhibition of Neel’s work, Elizabeth Hess commented how Neel’s "life and art were always connected” [1,2].

This paper aims to reveal the tangled interconnectivity of the relationships between Neel herself, with feminism, society and her art through the analysis of her female nude artworks. Specifically focusing on the artworks Childbirth (1939), Pregnant Maria (1964), a series of watercolors made in the 1930s and Self Portrait (1980), I would be connecting artworks with social, personal and feminist factors that may have contributed to the artwork. In doing so, I hope to elucidate the complex array of factors that all go into the artwork we see today, allowing the artwork to be a snapshot of the past and a signpost for the future. This paper would first be introducing different manners to which this paper would be analysing Neel’s female nude artworks (Alice Neel and Feminism, Alice Neel: The Sociologist? and Nudes). These sections would be foundational in the analysis of Neel’s art in later sections as these sections provide the context necessary to understand the full picture each artwork encompasses.

2. Feminism, Society and Art

These are the three aspects to which I would be analyzing Neel’s artwork. In Section 2, I would be giving the background of Neel with respect to Feminism, Society and Art (specifically art history and the female nude). This would serve as crucial background for the analysis of later artworks.

2.1. Alice Neel and Feminism

What is most striking, and perhaps most empowering, of Neel’s depiction of women that appeals to feminist spheres is the freshness of her brutally honest depictions of people of her portraits. Her ability to capture the individual character that extends beyond “social artifice” elucidated parts of women’s experiences that are omitted in Western art history and mainstream culture [3].

Many attributed Neel’s mainstream success to the Women’s Liberation Movement or the Second Wave Feminism as she seemed to have skyrocketed into popularity in the 1970s New York art scene with her acerbic wit and outlandish portraits [3]. Indeed, throughout her six-decade long career, it was only during the 1960s and 70s, after forty or so years of tenacious efforts, that during the Second Wave Feminism, she was propelled to mainstream popularity. However, being born in 1900 and entering society around 1920s and 30s, she did not identify perfectly with the 1960s’ feminist narrative. In the 1960s and 70s, the central issue that feminists championed is men’s oppression of women through their confinement in the designation of “nurturer-mother” [4]. Yet in an interview in 1975 with Feminist Art Journal’s Cindy Nemser, Neel refused to suggest that she had been victimized by men, saying, “’I don't think women should take any crap, any insults, any putting down; they should fight for all of it. But I don't think we should fight each other.... Both men and women are wretched and often it's a matter of how much money you have rather than what your sex is.’” [5].

In retrospect, the Second Wave Feminism was dominated by white, middle-class women [6]. While Neel admired their activism and acknowledges that their presence is essential in the progression of gender equality, it is white-centric with little acknowledgement of the intersectional layers of discrimination women of colour may face [2]. With that, she rebutted the hypocrisy of the Second Wave Feminists in her comments in the historic exhibition "Women Artists, 1550-1950" in 1976 Los Angeles County Museum of Art, she deliberately used diction that would grate the ears of an average feminist: "What amazed me was that all the women critics respect you if you paint your own pussy as a women's libber, but they didn't have any respect for being able to see politically and appraise the third world” [7]. For someone who often explored issues of class and race and consistently shown awareness for her white privilege through parody and humour in her art, Neel resented how her more radical artworks are glanced over by feminists at the time in favor of endorsing selective pieces from her repertoire [3].

In 1963, Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique was published. In three years, it sold 3 million copies in 3 years, becoming a phenomenon that marked the beginning of the second wave feminism. It rallied against “the problem that has no name”, introducing “systemic sexism”, popularizing the idea that the women’s place was as housewives and their unhappiness as a result are due to external factors, not a fundamental issue within the woman herself. Whilst the first wave feminists fought primarily for political equality, the overarching goal of second wave feminists is social equality [8,9].

While Neel gained traction as an artist during Second Wave Feminism, she did not align with the philosophy of Betty Friedan, rather, found another essential text in feminist anthology, The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir, to be preferable. In the meeting between Friedan and de Beauvoir, Friedan committed herself to “art or science, to politics or profession” in order to solve “the problem without a name”, whilst de Beauvoir declared that she intends to “sap this regime, not to play its game”, commenting how “working today is not liberty… The majority of workers are exploited.”, referencing Friedan’s tactics is attempting to garner equality within the economic system established by the patriarchy. In The Second Sex, de Beauvoir identifies two layers in which sexual inequality occurs. Firstly, she argues that the systematic inequality is due to society’s accordance to the masculine ideology that uses sexual differences to justify systems of inequality. Secondly, she identifies that those that subsequently advocate for equality assumes masculine as the norm, thereby erasing sexual difference, invalidating the female experience and allow the male form to be the ideal human form. As men are the standard, thereby considered “the privileged class”, for women to be admitted within the class, they must emulate men. However, the discriminatory differences between men and women remain as only those who are men or imitate them may “rule”. For de Beauvoir, men and women ought to treat each other as equals and this equality comes when the differences between the two are acknowledged and validated. Sameness is not equality [10, 11, 4]. This exact issue that de Beauvoir found within society is exactly what Friedan preaches: Friedan condemns the housewife role but encourages women to step into the field defined by men; therefore, “play[ing] its game” [4]. In other words, Friedan does not explicitly acknowledge the difference between men and women, instead, suggests for women to play in a man’s game, a game that de Beauvoir believes women would never be equal or win men.

Throughout most of her life, Neel was a single mother with an unstable income, a white woman who lived in what was called the Spanish Harlem, now known as El Barrio, a mostly Hispanic neighbourhood from 1938 to 1962. She had troubled relationships with men, her first as a young woman to a Cuban man, wherein her first child died during infancy and the other lived with her in-laws and another affair with a sailor which resulted in him burning several of her artworks [12, 3]. With her “bohemian” and tumultuous life, she had long forgone the American idealization of the nuclear family, confessing that she never finished the Feminine Mystique as “I couldn't identify with a housewife from Queens” [4, 5]. With all that said, Neel, much like de Beauvoir, refused to be victimized as a woman, commenting how both women and men are “wretched” and it is not about one’s sex but about “how much money you have” [5]. Here, she echoes de Beauvoir: instead of blaming women’s place in society on men, one needs to “sap this regime, not to play its game”, thus reconsidering the role of economics play within the social power of women, something in Friedan’s work addressed as a simply matter of working a day-job, instead of commenting on the reality of current society, which is the “wretched[ness]”, or essentially, how people would bypass your gender if you have enough money[4]. One cannot champion women’s rights with its solution as getting jobs (whose purpose is to obtain money) if the issue, fundamentally, comes with how society puts money, above all else, as the determinant factor of obtaining “equality” within society.

2.2. Alice Neel: The Sociologist?

Her complicated relationship with feminism and society is punctuated in her art as her depictions of her subjects, specifically female sitters, are reflective of societal changes and the sitter’s circumstances. Mary D. Garrard, a person who had been on the receiving end of Neel’s scrutinizing gaze in the artwork Mary Garrard (1977) once remarked that Neel had a particular “gambit” was “to discover and expose in her sitters the very things they would rather keep private” [13]. This gift of nailing the vulnerabilities of her subject in the midst of their attempts to mask is so fearsome that Joseph Solman, a fellow painter and a friend of hers during her tenure under the WPA (Works Progress Administration, part of the American New Deal), said that “If she did a portrait of you, you wouldn’t recognize yourself, what she would do with you. She would almost disembowel you, so I was afraid to pose for her” [14].

However, curators Kelly Baum and Randall Griffey as well as describes as Neel a “humanist” (also, Neel described herself as such), whose art served as a “buffer between multiple dehumanizing forces in America” [15, 16]. Rarely did she reduce her sitters as a mere archetype, discounting Irene and Eva (1972), a depiction of “suburban art mavens”, but as a collision of all of the social, economic, political, biological factors. Each of her sitters can fit into and identify with multiple issues regarding gender, race, class, sexual orientation or belief system on multiple different levels yet it is up to Neel to weigh which factor to accentuate in her portraits [17]. Neel neatly described her job to Phoebe Hoban, her biographer as she mentioned how she is “never arbitrary. Before painting I talk to my sitters and they unconsciously assume their most typical pose—which, in a way, involved all their character and social standing; what the world has done to them and their retaliation” [14]. Renowned sociologist Pierre Bourdieu put it more neatly with the academic term “habitus” which refers to "...the inscription of social power relationships on the body...at once produced and expressed through our movements, gestures, facial expressions, manners, ways of walking, and ways of looking at the world." [18]. Neel’s relationship between her portraits, the subject of the portrait and herself is that she is able to translate the subject’s habitus and condense it into discernable layers within her portraits.

In 1950, Alice Neel asserted, “For me, people come first, I have tried to assert the dignity and eternal importance of the human being” (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2021). As she paints a person, her connection with her subject is so strong that during the process, she said that “I become the person for a couple of hours, so when they leave and I'm finished, I feel disoriented. I have no self” [2]. For someone to be “disoriented” and identify so deeply with a subject that they have “no self” is indicative of Neel’s immersion into observation of a person and their place in society. Neel also does not refer to her portraits as “portraits” but “pictures of people”, strengthening the painter’s emphasis of the human quality of art, not just art for art’s sake [15]. She was not a sociologist, but merely an artist who recognized the complexities of each person that sat before her [17].

2.3. Nudes

Nudes are one of Neels most common forms of portraits; it is also how many of her most famous works, such as Pregnant Maria, Ethel Ashton and her self-portrait, are depicted. One inescapable issue that comes with the female nude is sexualization and objectification that has accompanied form religiously in Western art tradition. In Western fine arts, a female nude is not a woman per say, but a “woman”: someone vulnerable, passive, ageless and “the quintessential object of the male gaze” [2]. As Marxist critic John Berger in his book “Ways of Seeing”, he concluded that “Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at”, as such, Western art only replicate and solidify the unequal dynamic between genders in society [19, 20]. Moreover, art historian Lynda Nead describes “the transformation of the female body into female nude is thus an act of regulation: of the female body and of the potentially wayward viewer whose wandering eye is disciplined by the conventions and protocols of art” [21]. Female nudes previously presented are controlled presentation; these depictions of the female figure align with one’s social conception of a “woman”. This is why Neel’s female nudes are so essential and pivotal to this tradition: they "satirized the notion and the standards of the female body" [2].

Funnily enough, whilst being drawn unclothed seems rather intrusive experience, Mary Garrard notes wryly that the way Neel depicts nudity is “not particularly personal”. She goes on to say how nudity is “a mask”: the lack of clothing conceals your social identity, whilst your clothes merely “exposes your identity choices” [13]. On the flip side, Denise Bauer argues that depicting one unclothed aids Neel’s “search for ‘the complete person inside and outside”. She noted how instead of a casual or languid depiction of women seen in her contemporaries such as Isabel Bishop, her sitters almost seemed “pinned down in her studio like specimens” and her use of intense colours, flourishes in her brushwork as well as her ability to thoroughly gauge one’s facial expressions and body language gives her work “an unusual psychological intensity, an underlying anxiety” [2].

3. Analysis of Childbirth, Pregnant Maria, watercolour series, and Self Portrait

Here, this paper aims to analyze each of these artworks with respect to the aspects of Neel’s life and beyond discussed above. Through this process, I hope to reveal a holistic consideration of the artwork as well as the meaning Neel attempts to convey.

3.1. Childbirth

Pregnancy is rarely discussed in earnest in society, much less made a centerpiece in artworks prior to Neel’s work. And this lack of acknowledgement of what Neel comments to be “a basic fact of life”, according art historian Pamela Allara, can be attributed, in essence, to the fact that pregnant woman, as opposed to a non-pregnant woman, is a subject that the “controlling male gaze” cannot penetrate. As such, the controlling male gaze for which women are depicted in, the norm of Western fine arts, that allows for the erotization and objectification of the woman in question is no longer applicable to pregnant women. Perhaps the disquieting sensation of a norm breached, to put it bluntly, invokes fear; fear as the reality sets in where the woman’s ability to create something as fundamental as life dawns on the viewer [4].

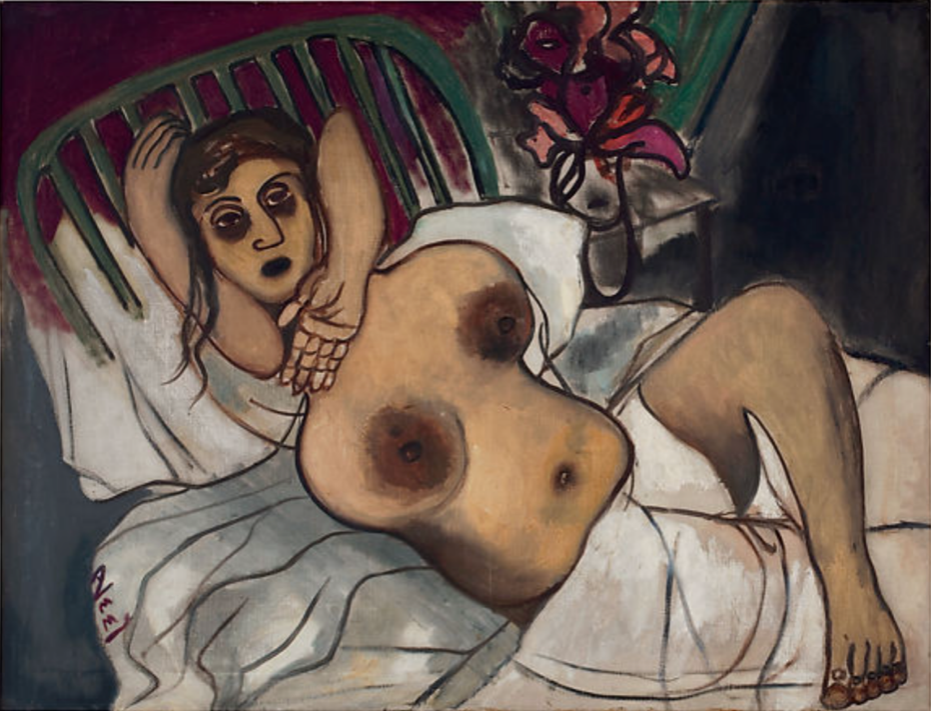

Figure 1: Childbirth, Oil on canvas, Alice Neel (1939) (Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

One of the few depictions of pregnant women in nude is by artist Gustav Klimt in his paintings Hope I, wherein the frankness of the model’s gaze in addition to the contradiction between the vitality of the pregnant woman and the motifs associated with death in the background further emphasizes the life that the woman is carrying, coalescing to form an image inspiring awe, but also fear [22]. The work was rejected for exhibition on the grounds of obscenity, indicative of society’s unease with the candid depiction of an unclothed, pregnant [23]. Their source of unease lies in people’s inability to see women beyond the roles they have subjugated, for which a plain display of something that does not fit into these roles (someone who is not a mother per say, but nor is an innocent young girl, yet she does not seem ashamed of her lack of innocence) incites fear [4].

Prior to the series done in 1964 to 1978, Neel has depicted pregnancy and post-partum women in early 1930s. In Couple on a Train in 1930, Neel depicted a couple on a train wherein the man sleeps peacefully, whilst the woman remains uncomfortable. In 1939, after she had just given birth to his son, Richard, Neel painted Childbirth (1939), depicting her hospital roommate Goldie Goldwasse post-partum.

It was only last year when Life Magazine published the infamous 35 paneled pictorial and 72-minute documentary titled The Birth of a Baby (1938). This issue caused protests world-wide, becoming banned in thirty-three US cities and in Canada. In spite of its purely scientific depiction of the process of childbirth with a noticeable lack of graphic displays, many condemned it to be “detrimental to the morals of youth” [24]. In retrospect, the pictorial, simple in layout, depicting childbirth looks rather unremarkable; the illustration of the baby emerging from the mother vagina is an illustration one can find on a textbook, the pictures accompanying the text obscured any graphic depictions, providing merely an educational vantage of the scene. In its essence, it was a neat and tidy portrayal of the birth of a baby with its aim of scientific education met.

In contrast, Neel’s Childbirth throws all rationality seen in the logical layout and immaculate portrayal in The Birth of a Baby out the window. The mother is exhausted; her limbs a tangled mess, her breasts swollen, dark half-moon cycles shadow her eyes. The loose brushstrokes, excessive shading in the breasts, stomach and pubic area is symbolic at the uncontrollability of Goldie’s body post-partum and the “twisted perspective” of the background adds a spinning sensation to the room, as if echoing the dizzying experience that is childbirth [2, 4].

On one hand, you have the almost complete omission of the female form in the Life Magazine, which still sparked controversy over obscenity lawsuits, versus Neel’s complete disregard for popular discourse (or lack thereof) of pregnancy and childbirth, with the discomfort and struggle that woman face post-partum displayed blatantly through a distorted exaggeration of the female figure. Here, one could say that in a situation where a sanitized, but honest portrayal of a process of life is considered to be morally detrimental is indicative of the lack of raw portrayal of life processes, specifically processes women endure that are socially unacceptable for men to experience, such as childbirth. Neel’s exaggeration of the female form in Childbirth constitutes a response to the charade that was the reception Life Magazine had [4]. The exaggeration, verging on distortion is to underline the pain that Neel, as a single mother herself, endured, visually contradicts to respond at the reception wherein a sanitized version of childbirth is still societally unacceptable.

It was around that time when other significant female artists, such as Frida Kahlo (My Birth and Henry Ford Hospital, both in 1932) and Maternity by Dorothea Tanning in 1946, explored this hitherto unacknowledged part of human existence. The reception of these artwork, including Neel’s Childbirth, can be neatly summed up by Whitney Chadwick, notable art historian, who remarked these artworks to be some of “the most disturbing images of maternal reality in twentieth century art” [2].

During 1964 to 1978, in junction with Neel’s blossoming family, with two of her sons beginning families, it was also during the heydays of the women’s liberation movement when Neel painted a series of seven portraits of pregnant nude women.

What is most significant of Neel painting pregnant women during the second wave feminism is how pregnancy is perceived by feminists and society at the time. Looking at the anthology of books that characterize the second wave feminism, such as Sisterhood is Powerful (1970), they all attributed women’s oppression in role as a housewife. Pregnancy occupies an odd place within feminism; it is what, in the most basic anatomical level, what our body does, but at the same time, it represents “the slavery of bourgeois female roles and identity”. During a protest on Mother’s Day in the 1970s Cleveland, a feminist cried, “Today, one day of the year, America is celebrating Motherhood, the other 364 days she preserves the apple pie of family life and togetherness and protects the sanctity of the male ego and profit. She lives through her husband and children…she is sacrificed on the alter of reproduction” [25].

Whilst pregnancy in of itself is not demonized, the role of housewives certainly is, which almost certainly entails pregnancy. By painting pregnant women, many feminists would gawk as it can be perceived as a suggestion for society to rebound to the idea of “anatomy is destiny” [4].

“It isn't what appeals to me, it's just a fact of life. It's a very important part of life and it was neglected. I feel as a subject it's perfectly legitimate, and people out of false modesty, or being sissies, never showed it, but it's a basic fact of life. Also plastically, it is very exciting.

“I think it's part of the human experience. Something the primitives did, but modern painters have shied away from because women were always done as sex objects. A pregnant woman has a claim staked out; she's not for sale.”

---- Alice Neel in an interview with Elizabath Hess, 1994 [26]

Not only that, Neel seems to step on a double taboo; not only are the women depicted pregnant, they are also painted nude. As author and curator of the Victoria and Albert Museum Gill Saunders notes in her book The Nude, “the image of the female nude has been emptied of women's experience, to be used by men as the expression of their sexuality” [27]. Yet even a superficial examination of Neel’s collection between 1964 to 1978, for which the portrait subjects ranged from her daughter-in-law, a neighbour, other artists or their wives and a friend of her son. The range of sitters suggests that Neel did not attempt to craft an “’essential’ experience of pregnancy”, instead, the sitters are, first and foremost, a person, thereby Neel’s observations are based individually. With no pretenses of attempting to create a frame of reference of pregnancy, Neel reiterates her stance of portraying pregnancy as a fact of life, something women from all walks of life experience and each woman would have a different experience. Having said that, what is important to note is that all but one of these women are identifiably middle-class and white, and what would be considered an ideal woman of the era. Yet with their swollen bellies and range of emotion is a shocking “intrusion”, a “distortion of the decade’s ideal” [4].

3.2. Pregnant Maria

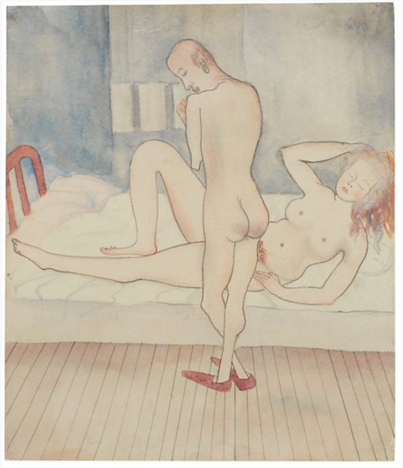

One of the earlier pieces from her series was Pregnant Maria (1964). The subject of the painting, Maria, was one of Neel’s neighbors in Spanish Harlem. With her limbs and protruding belly, she languidly reclines on the bed, staring directly at the viewer, reminiscent Manet’s groundbreaking work Olympia [2,4]. A white sheet beneath her, Neel subverts the academic treatment of a reclining nude draped with a white sheet with a “naked, nearly full term, pregnant woman” [2]. If Olympia was subversive for its lack of idealization of the female form in 1863, Neel furthers this subversion in her depiction of Maria through combining pregnancy with sexuality.

Figure 2: Pregnant Maria, Oil on canvas, Alice Neel (1964) (Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Painted in 1964, it is only four years after the birth control pill was launched in the United States, with 1.2 million women nationwide using it within two years [28, 29]. For most, the birth control pill promises the disconnect between sexual pleasure from its consequence. For second wave feminists specifically, it offers the autonomy for women to postpone pregnancy in favour of pursuing a career or degree. The Pill also facilitated in the enactment of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, prohibiting educational and employment discrimination, allowing women to enter the workforce [29]. With all of this, it also came the historical moment where sexual pleasure is disconnected from reproduction, yet with Pregnant Maria, Neel was able to reunite them, displaying a new generation of bohemian women who are unconcerned towards potential consequences of extramarital sex [4].

Maria is not the quintessential liberated woman whose liberation was brought by the Pill, but is, instead, reflective of the shifting attitudes towards women’s sexuality in the sixties. Between the cheap sheets, barren wall paper and dark circles beneath her eyes, it all suggests a decadent lifestyle in spite of a precarious monetary status. Whilst sensuous, Maria is no sex object, nor does she attempt to masquerade as the Virgin Mary. Allara suggests how her pregnant condition “inscribe[s]” her sexual history on her body, dispelling the idealization and fantasy of the male gaze, flipping one’s expectation of a female nude” [4]. With her matter-of-fact gaze towards the viewer and the quiet confidence of the comfortable manner she arranges her body, she is completely aware how she is presenting her body to be “surveyed” [4]. Her protruding belly and swollen breasts, highlighted by firm brushstrokes and clever lighting, only emphasizes her condition. For many viewers, they may wonder Maria, a woman in 1964, wherein the chance to forgo pregnancy for a more practical and career-oriented direction is readily available, why does this woman so blatantly display a condition, without fear for reputation or career, that is potentially going to be a burden? To the bourgeois viewer, she might be considered irresponsible, inconsiderate of the reality of her situation. Yet when one considers the personal background of Neel, she was once like Maria, sexually liberated, had four children with three, only one of whom she married, and went on to raise two children without a husband; perhaps painting Maria is partially due to personal motivation to represent what was once her reality [2,4]. On the other hand, Maria’s unapologetic attitude towards pregnancy and sexual pleasure, whilst contradictory to popular feminist discourse of the time, runs parallel to other artistic explorations, specifically Carolee Schneemann's performance art Meat Joy and the rise of Body Art, which focused heavily on the reclamation of women’s bodies and sexual liberation from the patriarchy [4].

3.3. Watercolor Series in the 1930s

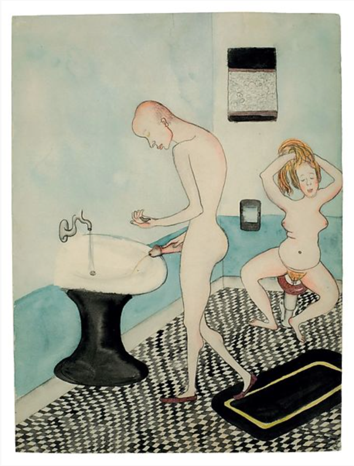

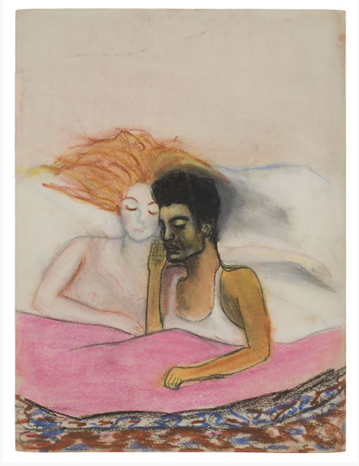

While her dedicated self-portrait was not painted until 1980, in a series of watercolors and pastels she did in the 1930s saw her detail her home and romantic life did include scenes of some of the most intimate, but also honest and candid artworks Neel has made. Alienation and Untitled (Alice Neel and John Rothschild in the Bathroom), drawn in 1935 are depictions of her affair with John Rothschild, while Alice and José and Untitled (Alice and José) are made in 1938 showing her relationship with the Puerto Rican musician José Santiago Negrón. It is praised by many great art historians, particularly feminist art historians such as Linda Nochlin, that her watercolors may be some of her most radical artworks, addressing taboo subjects. Nochlin also noted the precedence Neel set with these watercolors: she claimed a “territory” dominated by men, erotica art, for herself [30].

Figure 3: Alienation (1935)

Figure 4: Untitled (Alice Neel and John Rothschild in the Bathroom) (1935)

Figure 5: Alice and José (1938)

Figure 6: Untitled (Alice and José) (1938), Watercolor, Alice Neel (Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Baum, curator of People Comes First, elucidates the notability of this artwork by commenting how in erotic art in the past, women are objects whereas with the watercolors Neel painted, she is very much the “agent of desire”, suggesting a distinct character and autonomy hitherto unseen and unacknowledged [15]. With the watercolors depicting Neel with her lover John Rothschild, Baum, et al. argues how Neel attempts to “demystify” and “deromanticize” sex. In Untitled (Alice Neel and John Rothschild in the Bathroom), the couple are in the bathroom, seemingly either in the preamble or aftermath of a sexual encounter. Neel urinates into the toilet whilst Rothschild in the sink; Neel is fixing her hair while Rothschild inspects his nails. The mutual disinterest of both characters in spite of their nudity amplifies the disinterest the couple have of each other. This is further extended upon in Alienation. Neel, the pose of an oblique, stiff, Rothschild stands over her with his arms hugging his torso. The two look away from each other, furthering the emotional distance despite their physical nearness [30].

Whether portraying a passion-filled encounter or a distant relationship, instead of adopting a sentimental, romanticized lens, Neel treats each of these scenes with almost frightful, “radical honesty” [30]. This sentiment is also shared by Jeremy Lewison as he mentions while many of Neel’s social realist contemporaries dwelled on “lachrymose” sentimentality and political mass panic, Neel always find a way to pierce beyond her sitter’s skin and “penetrate through to the psychological strengths and frailties of her sitters” [31,32].

It is also noted that this series of watercolor were created just after the inception of the Motion Picture Production Code, otherwise known as the Hay Code. The Hay Code was a response to overwhelmingly explicit content of movies used by studios to lure in audiences in 1930 to 1934, which was during the Great Depression. It was a set of guidelines imposed on all motion pictures released between 1934 and 1968 and prohibited “profanity, suggestive nudity, graphic or realistic violence, sexual persuasions and rape” [33]. It signalled an era of ultra-conservatism in media. Neel’s watercolors does not abide in “spirit” or “letter” of the Code. While one cannot give the Hay Code complete credit for Neel’s motivation to produce explicit content, in fact, I believe because of the Hay Code, she never intended for these watercolors to be viewed in public. These watercolors, indeed, was only available to the public in the 1970s, after the Hay Code has fallen [33, 30]. While her irreverence for public opinion could interpret these artworks as a direct rebuttal to the Code, I believe the connection between the two lies in how the Hay Code stifled possibility of realistic and honest representation of love. Curator Chelsey O’Brien even noted there are limits in the Code about pure love or realistic love, some things as ordinary as married couples sleeping in the same bed was prohibited [33]. The lack of candor in media representation may have irritated Neel, whom, as mentioned, treated her sitters and subject with “radical honesty”, for which her search for honesty in presenting mundane things deemed illegal came in the form of these watercolors [30].

It is also possible Neel was unconsciously tapping into some of the intellectuals of the 1910s in Greenwich village (Baum, et al., 2021). The monthly newspaper The Masses, edited by notable writers Floyd Dell, Max Eastman, Ethel Bryne, Margaret Sanger and more was also contributed by Neel’s friend Mike Gold. Beyond fighting against gender and class inequality, this community in Greenwich village also embraced what they call “sexual modernism” or sexual liberation (of both men and women) [30, 34]. During the time when these artworks are created, Neel was living in Greenwich Village, surrounded by bohemian contemporaries on par with those in 1910s [16]. Conscious or not, Neel tapped into the essence of those in the 1910s when she commenced her own sexual revolutions 2 decades later [30]. Furthermore, she also joined the Federal Art project and the Communist party in 1935, for which one could percieve her personal political and sexual revolutions to be intertwined [15]. The last artworks of this series were made around 1938, the same year she moved from Greenwich to Spanish Harlem [16].

Some, most notably author, advisor of the Alice Neel Estate in 2003 to 2020 and former director of Tate Gallery Jeremy Lewison, theorized that Neel’s dedication to portraiture and in the depiction of people was derived from her time in the psychiatric ward after she had a nervous breakdown in early 1930s [32, 35, 36]. Her interest in painting people extends beyond mere representation of another but can be assigned to her “psychological interest”, for which when she is engaging in the people she is painting, it is also an exercise for which she is engaging herself; “the paintings are as much a portrait of her as they are a portrait of the person she’s portraying” [37]. This view was concurred by many, including Baurer in 1994, mentioning how her artworks contain a “psychological intensity” [2].

3.4. Self Portrait

It was only in 1980, Neel at the height of her fame, when she produced her first and only self-portrait—ironically titled: Self Portrait. What is most striking is perhaps what is most obvious of the self-portrait: Neel’s nakedness. In a misogynistic society that idealizes youth and where women’s bodies are rarely portrayed realistically in fine arts or mainstream culture, if at all, Neel turns her uncannily scrutinizing gaze to her own body, depicting it with all its beauty and “flaws”. In Figure 8, her nakedness here contributes two-fold: firstly, it furthers the appropriation of the long-standing artistic tradition of artists’ self-portraits, but it also furthers the movement seen in contemporary feminist artists that “foregrounds” their nude or semi-nude bodies in order to subvert power imbalances in gender, sex and art [38].

Figure 8: Self Portrait, 1980, Oil on Canvas, Alice Neel (Courtesy of Alice Neel Estate)

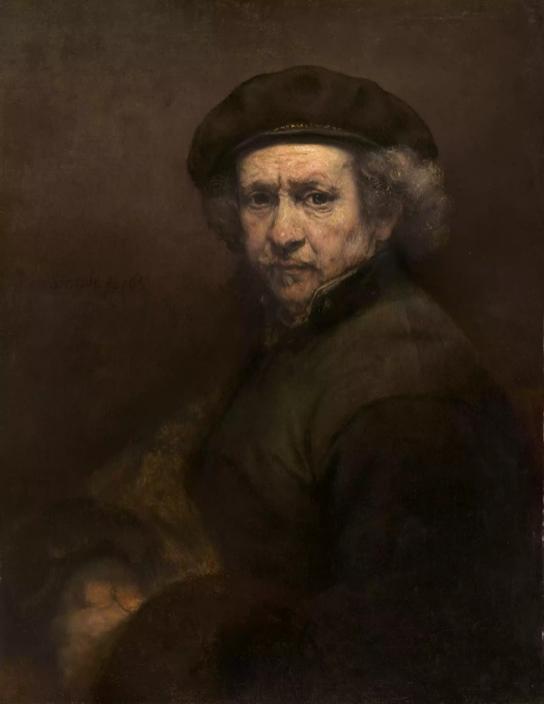

As the Kelly Baum, co-curator of the “People Come First”, an exhibit dedicated to Neel’s entire career in 2021 as well as Mary Garrard, a sitter and associate of Neel, mentions, Neel knows her art history well, cleverly weaving intertextual references of significant and obscure artworks with her own artworks [13,15]. This was exemplified in Pregnant Maria, where the pose of Maria mirrors the pose of Manet’s Olympia [2, 4]. With her self-portrait, while broadly enriching to the tradition of artist self-portraits, her aging form can draw comparisons to another artist who famously documented his own aging through self-portraits: Rembrandt [39]. In Rembrandt’s Self Portrait (Figure 9), he too gazes directly at the viewer, his pre-mature wrinkles prominent on his faces, and as the National Gallery states, it is impossible to look at this image and not wonder what happened to this man; “…we read these images biographically because Rembrandt forces us to do so. He looks out at us and confronts us directly. His deep-set eyes peer intently…” [40, 41]. Yet in spite of the hardships he endured (it was the same year his assets and estate was seized due to bankruptcy), various details, such as his pose, the lighting and the expression, all echo another legendary artist he admire: Raphael. All of this seems to suggest that in spite of the toll his failures have taken on him, physically and mentally, this self-portrait makes clear that his own self-respect and dignity remains [40]. Beyond both artworks having the same name, both artists directed their gaze towards to viewer in order for the viewers to confront an uncomfortable reality: Rembrandt of his dignity in spite of his failures, and Neel of her irreverence for dignity in spite of her aged body and nudity. Whilst Rembrandt seems to preserve his dignity through fine clothes and art, Neel seems to laugh in face the face of this notion of “dignity”, instead, takes away all her defenses and leaves herself unclothed, parodying herself. Yet it is the fact that Neel does not take to the notions of dignity set by society that she exemplifies her own self-respect and dignity as it demonstrates her self-dignity in spite of whether societal norms are followed [13]. Bridget Quinn, writer and art history scholar, comments how while Rembrandt’s series of self-portraits throughout his life catalogued his triumphs and defeats (here, specifically his defeats), as if his own “weary personal testaments to the ravages of time”, Neel’s self-portrait is unapologetic, both towards herself and the way she presents herself to the world (2017). Neel’s self-portrait enriches this tradition for her defiance to what she was “supposed” to do or paint, her blatant realism spins the art world with a mix of delight and horror. This self-portrait was her retaliation to the “art world, art history and its woes”: it is not a bitter depiction, but a “playful affirmation of the absurdity of the human condition” [39].

The way Neel enriches this artistic tradition is also through her unique “feminist” take. I say “feminist” because I believe her actions while it defies the patriarchy, her motivation for doing such acts, fundamentally, does not stem from deliberately trying to create a feminist work, but comes from a personal distaste and disregard for backwards traditions. According to Mary Garrard, there are three specific manners where Neel defied artistic tradition: firstly, the lack of male gaze, secondly, symbolism, and thirdly, the display of her unfiltered body. All are significant to why this self-portrait is such a significant moment in art history.

Figure 9: Self-Portrait, 1659, Oil on Canvas, Rembrandt van Rijn, National Gallery of Art.

The objectification of women in art and art history is so ubiquitous that it is normal; in fact, a deviation with a woman portrayed with vitality and individuality is often met with exaggerated outrage [17]. Her “high-flown” brows, familiar to all who have applied mascara with a mirror, suggests her concentration, indicates Neel was using a mirror for her self-portrait, referencing Neel’s reticence throughout her life to use photographs, instead preferring to sit with the person: “desiring the pulse of personhood and emotion beneath real flesh” [39]. Another detail the revolts against the objectification of woman is that Neel was wearing glasses. As poet Dorothy Parker comments, “Men seldom make passes / At girls who wear glasses.” Although subtle, it carries the symbolic meaning of not dressing for men but also carries forth a utilitarian tone to Neel’s interpretation of herself, reminder of Neel’s profession (mostly to male audiences), which contradicts the escapist tendencies of the nude [39]. On the other hand, some interpret eye glasses as an indication of her age, but argues that glasses proclaim herself as the one that “sees”, referencing her work but also her keen observation.

Beyond the semiotics concerning glasses, there is also the symbolism behind the brush Neel holds in her right hand [39, 13]. Neel is actually left-handed, and her right hand holds the brush. In many cultures, including popular culture, but also in Christian religions, the right hand is associated with men, the left with women; the right with spiritual, the left with secular; the right with the righteous, the left with sinners [41,42]. By holding the brush in her right hand, she deliberately courts and challenges the masculine norm of art. Another example of Neel’s extensive understanding of art history, paintbrushes in paintings from artists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner are strategically positioned at the groin in their self-portrait. This furthers the symbolic relationship between the penis and the paintbrush, reiterate the “machismo” of art. While in Neel’s portrait, the brush is located at the crook of her arm, “artistic virility” is merely transferred to directly below the brush, with the shape of the painter’s right foot. By incorporating a sexual element that would typically be associated with vitality and youthfulness, it is as if Neel is “pulling the lumpen shapes of a sagging, aging body into aesthetic harmonies of pure design”, parodying the machismo of art and reclaiming sexuality even as an old woman [13].

“Neel was an artist who, for all of her irreverence and radicalism, operated within art history’s dominant genres,” analyzed Kelly Baum, co-curator of Neel’s exhibit “People Come First”. She operated both “inside and outside” of art’s traditional genres by still abiding by the pillars that make the genre recognizable, but subverts and adapts these elements to reflect her view of the world. Randall Griffer, co-curator of “People Come First”, comments how Neel’s bodies are distinctly imperfect as she thought humanity was “beautifully imperfect”. Much like the pregnant women Neel depicted, Baum mentions how the body Neel depicted in her self-portrait is one that does not have a place in art history, and “its absence” is something Neel wanted to rectify [15].

4. Conclusion

Neel once said that one of the reasons she painted was so that she can “catch life as it goes by”. She also believed there is no set “iconography” that differentiates a man’s work from a woman’s work. In fact, a colleague of hers once said, “Alice Neel, the woman who paints like a man”, to which she replied, “No, I paint like a woman”. Her art is not important because she is a woman, but because she is unflinchingly honesty and fearless in face of subject’s others would shy away from. Her honesty, keen observation, and sensitivity to the political and social climate are why these female forms are so crucial: they represent a moment in time, for which the moment had gone against the constraints of time. In doing so, she “capture[d] the zeitgeist”, proudly and unapologetically displayed the hidden and unrepresented, immortalizing them in art. In doing so, she immortalized the realities of being a woman, a lover, a mother and many, many more.

References

[1]. References Neel, A. (1971) By Alice Neel. Daily World.

[2]. Bauer, D. (1994) Alice Neel’s Female Nude. Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 15, no. 2: 21–26.

[3]. Bauer, D. (2002) Alice Neel’s Feminist and Leftist Portraits of Women. Feminist Studies, vol. 28, no. 2: 375–395.

[4]. Allara, P. (1994) Mater’ of Fact: Alice Neel’s Pregnant Nudes. American Art, vol. 8, no. 2: 7–31.

[5]. Neel, A., Nemser, C. (1975) Alice Neel: The Woman and Her Work. Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia, Athens, GA.

[6]. Pruitt, S. (2022) What Are the Four Waves of Feminism?. https://www.history.com/news/feminism-four-waves.

[7]. Harris, A.S., Nochlin, L. (1976) Women Artists, 1550-1950. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles.

[8]. Grady, C. (2018) The Waves of Feminism, and Why People Keep Fighting over Them, Explained. https://www.vox.com/2018/3/20/16955588/feminism-waves-explained-first-second-third-fourth.

[9]. Friedan, B. (2010) The Feminine Mystique. Penguin, London.

[10]. Bergoffen, D., Burke, M. (2020) Simone De Beauvoir. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/beauvoir/.

[11]. Beauvoir, S.D. (1949) The Second Sex. Penguin Books, London.

[12]. Molesworth, C. (2000) Alice Neel and Others. Salmagundi, no. 128/129: 58–71.

[13]. Garrard, M.D. (2006) Alice Neel and Me. Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 27, no. 2: 3–7.

[14]. Hoban, P. (2010) Alice Neel: The Art of Not Sitting Pretty. St. Martin’s Press, New York.

[15]. metmuseum. (2021) Alice Neel: People Come First Virtual Opening | Met Exhibitions. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ejGERwLV2Kg.

[16]. Alice Neel Estate. (2021) About Neel. https://www.aliceneel.com/about-neel/.

[17]. Allara, P. (2006) Alice Neel’s Women from the 1970s: Backlash to Fast Forward. Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 27, no. 2: 8–11.

[18]. Moi, T. (2008) What Is a Woman? and Other Essays. Oxford University Press, Oxford. pp. 59.

[19]. Berger, John. (1972) Ways of Seeing (Modos De Ver). BBC and Penguin, London.

[20]. Tate. Feminist Art. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/feminist-art.

[21]. Nead, L. (1992) The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality. Taylor & Francis Group, London. pp. 6-7.

[22]. themoenen. Gustav Klimt - Hope I, 1903. https://arthur.io/art/gustav-klimt/hope-i.

[23]. Gustav-Klimt.com. (2011) Hope I, 1903. https://www.gustav-klimt.com/Hope-I.jsp.

[24]. S.Za. (2010) The Birth of a Baby. https://iconicphotos.wordpress.com/2010/12/01/the-birth-of-a-baby/.

[25]. Umansky, L. (1996) Motherhood Reconceived: Feminism and the Legacies of the Sixties Clauri Umansky. New York University Press, New York.

[26]. Hess, E. (1994) Artist and Models. Village Voice.

[27]. Saunders, G. (1989) The Nude: A New Perspective. Herbert Press, London.

[28]. Bridge, S. (2007) A History of the Pill. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2007/sep/12/health.medicineandhealth.

[29]. American Experience. The Pill and the Women's Liberation Movement. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/pill-and-womens-liberation-movement/.

[30]. Baum, K., et. al. (2021) Alice Neel: People Come First: Travelling Exhibition, USA, Europe, 2021. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

[31]. Lewison, J. (2015) ALICE NEEL Drawings and Watercolors 1927–1978, David Zwirner Gallery Press Preview. https://dailyartfair.com/events/download_press_release/3831.

[32]. Lewison, J. Jeremy Lewison: Alice Neel Estate. https://www.jeremylewison.co.uk/alice-neel-estate.

[33]. Lewis, M. (2021) Early Hollywood and the Hays Code. https://www.acmi.net.au/stories-and-ideas/early-hollywood-and-hays-code/.

[34]. Buhle, M.J., et al. (1998) Encyclopedia of the American Left. Oxford University Press, New York.

[35]. Lewison, J. Jeremy Lewison Ltd. https://www.jeremylewison.co.uk/.

[36]. Hufkens, X. (2015) Alice Neel – A Conversation between Helen Simpson and Jeremy Lewison. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xhyAurBklQI

[37]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Self-Portrait. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/827227?exhibitionId=%7Bebc2cd20-ef8a-48a4-b327-7e037956caa6%7D&oid=827227&pkgids=682&pg=0&rpp=20&pos=104&ft=%2A&offset=20.

[38]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Self-Portrait. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/827227?exhibitionId=%7Bebc2cd20-ef8a-48a4-b327-7e037956caa6%7D&oid=827227&pkgids=682&pg=0&rpp=20&pos=104&ft=%2A&offset=20.

[39]. Quinn, B. (2017) Alice Neel: How to Persevere and Live the Artist's Life. https://lithub.com/alice-neel-how-to-persevere-and-live-the-artists-life/.

[40]. Marder, L. (2020) Rembrandt's Self-Portraits. thoughtco.com/rembrandts-selfportraits-4153454.

[41]. National Gallery. Self-Portrait. https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.79.html.

[42]. The Met. (2020) Alice Neel: They Are Their Own Gifts, 1978 | From the Vaults. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f-uFOf9p69s.

Cite this article

Hsu,C. (2023). Alice Neel’s Female Nudes: Society, Feminism and Art. Communications in Humanities Research,3,639-653.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies (ICIHCS 2022), Part 1

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. References Neel, A. (1971) By Alice Neel. Daily World.

[2]. Bauer, D. (1994) Alice Neel’s Female Nude. Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 15, no. 2: 21–26.

[3]. Bauer, D. (2002) Alice Neel’s Feminist and Leftist Portraits of Women. Feminist Studies, vol. 28, no. 2: 375–395.

[4]. Allara, P. (1994) Mater’ of Fact: Alice Neel’s Pregnant Nudes. American Art, vol. 8, no. 2: 7–31.

[5]. Neel, A., Nemser, C. (1975) Alice Neel: The Woman and Her Work. Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia, Athens, GA.

[6]. Pruitt, S. (2022) What Are the Four Waves of Feminism?. https://www.history.com/news/feminism-four-waves.

[7]. Harris, A.S., Nochlin, L. (1976) Women Artists, 1550-1950. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles.

[8]. Grady, C. (2018) The Waves of Feminism, and Why People Keep Fighting over Them, Explained. https://www.vox.com/2018/3/20/16955588/feminism-waves-explained-first-second-third-fourth.

[9]. Friedan, B. (2010) The Feminine Mystique. Penguin, London.

[10]. Bergoffen, D., Burke, M. (2020) Simone De Beauvoir. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/beauvoir/.

[11]. Beauvoir, S.D. (1949) The Second Sex. Penguin Books, London.

[12]. Molesworth, C. (2000) Alice Neel and Others. Salmagundi, no. 128/129: 58–71.

[13]. Garrard, M.D. (2006) Alice Neel and Me. Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 27, no. 2: 3–7.

[14]. Hoban, P. (2010) Alice Neel: The Art of Not Sitting Pretty. St. Martin’s Press, New York.

[15]. metmuseum. (2021) Alice Neel: People Come First Virtual Opening | Met Exhibitions. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ejGERwLV2Kg.

[16]. Alice Neel Estate. (2021) About Neel. https://www.aliceneel.com/about-neel/.

[17]. Allara, P. (2006) Alice Neel’s Women from the 1970s: Backlash to Fast Forward. Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 27, no. 2: 8–11.

[18]. Moi, T. (2008) What Is a Woman? and Other Essays. Oxford University Press, Oxford. pp. 59.

[19]. Berger, John. (1972) Ways of Seeing (Modos De Ver). BBC and Penguin, London.

[20]. Tate. Feminist Art. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/feminist-art.

[21]. Nead, L. (1992) The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality. Taylor & Francis Group, London. pp. 6-7.

[22]. themoenen. Gustav Klimt - Hope I, 1903. https://arthur.io/art/gustav-klimt/hope-i.

[23]. Gustav-Klimt.com. (2011) Hope I, 1903. https://www.gustav-klimt.com/Hope-I.jsp.

[24]. S.Za. (2010) The Birth of a Baby. https://iconicphotos.wordpress.com/2010/12/01/the-birth-of-a-baby/.

[25]. Umansky, L. (1996) Motherhood Reconceived: Feminism and the Legacies of the Sixties Clauri Umansky. New York University Press, New York.

[26]. Hess, E. (1994) Artist and Models. Village Voice.

[27]. Saunders, G. (1989) The Nude: A New Perspective. Herbert Press, London.

[28]. Bridge, S. (2007) A History of the Pill. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2007/sep/12/health.medicineandhealth.

[29]. American Experience. The Pill and the Women's Liberation Movement. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/pill-and-womens-liberation-movement/.

[30]. Baum, K., et. al. (2021) Alice Neel: People Come First: Travelling Exhibition, USA, Europe, 2021. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

[31]. Lewison, J. (2015) ALICE NEEL Drawings and Watercolors 1927–1978, David Zwirner Gallery Press Preview. https://dailyartfair.com/events/download_press_release/3831.

[32]. Lewison, J. Jeremy Lewison: Alice Neel Estate. https://www.jeremylewison.co.uk/alice-neel-estate.

[33]. Lewis, M. (2021) Early Hollywood and the Hays Code. https://www.acmi.net.au/stories-and-ideas/early-hollywood-and-hays-code/.

[34]. Buhle, M.J., et al. (1998) Encyclopedia of the American Left. Oxford University Press, New York.

[35]. Lewison, J. Jeremy Lewison Ltd. https://www.jeremylewison.co.uk/.

[36]. Hufkens, X. (2015) Alice Neel – A Conversation between Helen Simpson and Jeremy Lewison. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xhyAurBklQI

[37]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Self-Portrait. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/827227?exhibitionId=%7Bebc2cd20-ef8a-48a4-b327-7e037956caa6%7D&oid=827227&pkgids=682&pg=0&rpp=20&pos=104&ft=%2A&offset=20.

[38]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Self-Portrait. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/827227?exhibitionId=%7Bebc2cd20-ef8a-48a4-b327-7e037956caa6%7D&oid=827227&pkgids=682&pg=0&rpp=20&pos=104&ft=%2A&offset=20.

[39]. Quinn, B. (2017) Alice Neel: How to Persevere and Live the Artist's Life. https://lithub.com/alice-neel-how-to-persevere-and-live-the-artists-life/.

[40]. Marder, L. (2020) Rembrandt's Self-Portraits. thoughtco.com/rembrandts-selfportraits-4153454.

[41]. National Gallery. Self-Portrait. https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.79.html.

[42]. The Met. (2020) Alice Neel: They Are Their Own Gifts, 1978 | From the Vaults. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f-uFOf9p69s.