1. Introduction

Animal eating broadcasts are a form of video that has gradually become popular on various social media in recent years. In September 2018, the YouTube channel Mayapolarbear uploaded a video of Maya, a Samoyed, eating watermelon, which received more than one million views. To some extent, Maya’s video of her eating watermelon is the earliest animal eating broadcast [1]. Since then, more and more pet bloggers who mainly photographed animals’ daily lives have begun to turn to photographing animals eating. Since China launched the “Clean Plate Campaign”, some unreasonable human eating broadcasts have been banned. The censorship of such videos has become stricter, and the creators have turned their attention to non-humans. Therefore, animal eating broadcasts were introduced to the Chinese market, and many pet bloggers on various online video platforms began to try this format and gained good viewing volume. For example, in the account of a blogger (Huahua and Sanmao CatLive) with more than 3 million followers on the online video platform bilibili, one of the albums contains a series of videos of the blogger’s pet cat eating various foods. The number of views of the videos in this album is higher than that of the videos in this blogger’s other albums about games and daily life [2]. Some commentators mentioned that China’s current animal eating broadcast accounts span the two major areas of eating broadcasts and cute pets on social media [1]. From this point of view, animal eating broadcasts may share the content characteristics and influences of videos in both fields.

The online audio-visual broadcast that features the creator or host eating food originated in South Korea, and it also has a specific term, “mukbang.” The term “mukbang” is a combination of “eat” (meokneun) and “broadcast” (bangsong) in Korean, and since the late 2000s, Korean eating broadcast has become increasingly popular [3]. Nowadays, the term mukbang is widely used in daily entertainment life, academic research, and other scenarios. In this study, the term “animal mukbang” will also refer to the type of animal eating broadcast. Some of the mukbang videos which the human is the protagonist often show an exaggeration by amplifying the sound of eating and close-up images of food while others talk to the audience, commenting on the multisensory experience of the food consumed—taste, smell, texture, and appearance [4]. Moreover, viewers can also experience a sense of compensation by watching mukbang videos and gain satisfaction from the eating behavior of others. According to Anjani et al., mukbang also provides viewers with a psychological connection to others [4].

Another category of videos that animal mukbang belongs to is cute pet videos. In this type of video, animals are often given human characteristics to attract more viewers. Similarly, in animal mukbang videos, animals often “imitate” humans. These videos often take a similar format to regular human mukbang, such as eating novelty foods, wearing nice clothes, and even resembling human eating environment, like the table where they eat, the cutlery for eating, and the microphone for recording. These forms are very similar to human mukbang and can also give viewers a similar sense of compensation and multi-sensory experience [2]. In addition, the sense of psychological connection that can be generated by human mukbang can also be reflected in animal mukbang. For example, Choe found that cat mukbang videos provide a feeling of being with cats and it is a spin-off of mukbang [5]. In this case, mukbang is an online zoo that offers viewers virtual encounters with cats. In general, most animal mukbang videos are in line with the creative idea of animal videos on social media, which is to tell stories by giving animals human characteristics. In other words, animal mukbang seems to give animals human characteristics, thereby making the audience produce a similar psychological mechanism as watching human mukbang.

Animals on social media are often given human-like characteristics, driven by humans’ natural desire to make connections even with non-humans [6], a phenomenon known as anthropomorphism. Although anthropomorphism is very common in animal videos, the ethical considerations surrounding anthropomorphic representations have still been controversial. Related research often focuses on the analysis of anthropomorphic content elements in various media such as film, book, and photography. For example, Weil has analyzed Frank Noelker’s (a plastic artist) photographs of chimpanzees in contrast to his earlier Captive Beauty: Zoo Portraits, which focused on showing animals in environments fully shaped by humans, in this artificial environment, the image of animals appears unreal [7]. Besides, Noelker often emphasizes anthropomorphism by focusing on animals’ eyes, such as chimpanzees. Noelker is excellent at capturing the heavy, deep, and personal gaze the chimpanzees cast upon us, thoughtful, critical, and, some might say, almost human-looking. This example was mentioned in Weil’s study of “critical anthropomorphism,” which refers to finding ways of relating to non-human animals, considering their interests, not just human’s [7]. In addition, Malamud explores the scope and manifestations of harm, such as whether there are other damages to animal rights besides visible physical harm [8]. Malamud points out that in some movies, animals do things to please the audience, the things refer to that they usually don’t do and have no reason to do, such as dancing bears, playing chickens on the piano, chimpanzees dressed in human clothing, and so on [8]. Similarly, some people have questioned the behavior of animals eating human food or eating large amounts of food in animal mukbang. They believe that this does not respect the natural characteristics of animals but is intended to satisfy the curiosity of some people [1]. However, in some specific media, anthropomorphism may not have such a strong negative impact, such as anthropomorphic language and pictures in children’s storybooks [9].

While there have been a number of studies on the anthropomorphism of animals, research about anthropomorphism in animal mukbang is scarce. More importantly, two questions remain unsolved. First, there is a lack of a systematic summary of anthropomorphic elements in animal mukbang videos. Second, limited attention has been paid to the factors influencing people’s attitudes toward anthropomorphizing animals on social media. Therefore, this study aims to address these two questions by studying animal mukbang. Previous studies have demonstrated that anthropomorphism depends not only on the characteristics of specific animals but also on the interaction and relationship between humans and animals [10]. From this perspective, it is worth noting whether the audience’s experience with animals will affect their perception of anthropomorphism. In general, this study aims to first summarize the anthropomorphic elements systematically in animal mukbang videos and explore how specific factors influence audience acceptance of anthropomorphic elements. Since the research on mukbang rarely pays attention to Chinese social media, this study takes Douyin and Xiaohongshu as examples to explore the anthropomorphic elements in animal mukbang videos through content analysis. Subsequently, based on the anthropomorphic elements that have been summarized, a questionnaire survey is conducted to investigate the acceptance of different audiences.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Mukbang and audience motivations

Previous studies on human mukbang mostly focus on the summary of the content framework, the mechanism of popularity, the psychological mechanism of the audience, and the impact of watching mukbang videos. According to Sultana and Das’s content analysis of different mukbang video texts, a total of 6 content themes were summarized, including food preparation, food video location, cuisine, food type, food consumption/eating amount, and type of eater [11]. They also investigated whether different elements would affect the ratings of mukbang videos, such as the diversity of cuisine and food type, and the exquisite and beautiful food preparation will greatly increase the audiences’ interests visually, thereby increasing the number of views. Moreover, the overeating behavior of eaters also attracts more views due to its entertainment value. In addition to understanding mukbang from the perspective of video content, the audiences’ viewing motivation can also provide a deeper explanation for the popularity of mukbang videos. According to existing related research, the main theoretical frameworks used are the Uses and Gratification Theory (U>) and the Compensatory Internet Use Model (CIUM), both of which provide different analytical bases for users’ motivations to watch mukbang. According to Ruggiero, the uses and gratification theory emphasizes the audience’s agency and selection motivation in media consumption, that is, the audience actively seeks media to meet specific needs [12]. Lariscy et al. also pointed out that the basic premise of the uses and gratification theory is that individuals look for media that can meet their needs and bring ultimate satisfaction to competitors [13]. Song et al. used the U> theoretical framework to summarize the audience’s motivations for watching mukbang videos, which mainly include seeking alternative satisfaction, enjoying the entertainment of the content, seeking information about food, watching specific mukbang content, and watching specific mukbang hosts [14]. Their research focused on the concept of vicarious satisfaction, which means that the audience does not eat by themselves, but experiences happiness and satisfaction by observing the host eating and describing the food. Anjani et al. also pointed out that watching mukbang videos can give the audience an indirect food experience and produce a vicarious pleasure [4].

In addition, Kircaburun et al. explained the audience’s motivation for watching mukbang from the perspective of the Compensatory Internet Use Model [15]. According to Kardefelt-Winther, Compensatory Internet Use refers to people’s use of the Internet to relieve the negative emotions caused by negative life situations [16]. In other words, specific online activities are used to compensate for unfulfilled offline needs, such as socializing. Kircaburun et al. used CIUM to explain the five psychological characteristics of viewers watching mukbang videos, including social use, sexual use, entertainment use, escapist use, and ‘vicarious eating’ use [15]. Among them, entertainment and vicarious eating refer to the richness of the content and the psychological satisfaction of the audience with food, respectively. In addition, “social use” mainly refers to the fact that mukbang can allow viewers to feel the company of others in a virtual environment, thereby promoting emotional connections and making up for the lack of social experience in reality. This compensation for the negative aspects of real life can also be reflected in the “escapist use,” where viewers relieve the stress or boredom of daily life by watching mukbang videos and temporarily escaping from the unpleasant real life. Moreover, some viewers are attracted by the appearance of the eaters, which corresponds to the psychological characteristic of “sexual use.” According to Pereira et al., the physical attractiveness of the mukbangers is positively correlated with the audience’s attitude towards mukbang [15]. This further proves the important influence of the mukbanger’s image on the popularity of mukbang videos. In addition, some people may combine sex with food satisfaction to form a fantasy of eating, which is more arousing [15].

In summary, although the research on the content and viewing motivation of mukbang videos is relatively comprehensive, they all focus on mukbang videos with humans as the eaters, and there is a lack of relevant research on animal mukbang. When the protagonists of mukbang are replaced by animals, whether the vicarious satisfaction, the attractiveness of the eaters, the entertainment of the content, etc. mentioned in previous studies will still exist, and how animal mukbang videos produce similar effects to human mukbang, these issues need to be explored. Before understanding these issues, it is necessary to review the content framework of animal mukbang, but due to the lack of relevant research, this study first starts with the research on animal video content in social media to understand the popularity mechanism of such short videos with animals as the protagonists.

2.2. Animal videos on social media

This study draws on research on animal videos to understand the conventions and popular factors in their creation. First, Zhang and Zhu detailed the content characteristics of short videos on Douyin featuring cute pets, which included not only the cute appearance of animals but also the personalities given to the animal protagonists by viewers and bloggers, as well as anthropomorphic narrative techniques, such as dressing the cat in beautiful clothes and preparing exquisite food for it [17]. Second, O’Meara studied dog videos on YouTube, pointing out that in some videos, dogs seem to be looking at the camera and talking to the photographer, and sometimes dogs even seem to show guilt and shame to the observer [18]. In addition to the interpretation of video texts, some studies have also investigated the popularity of different animal video content from the perspective of viewers. Stumpf et al. summarized the popular animal video content [19]. In their survey, these categories were watched by more than 50% of the participants, namely, “Animal has been trapped,” “Challenge that owners set with an animal,” “Animal wore human clothes or costumes,” “Animal mishaps,” and “Animal did something extraordinary” (such as facial expressions, gestures, vocalizations). Among them, more than 90% of the participants watched the content “Animal did something extraordinary,” and more than 80% of the participants watched the content “Animal wore human clothes or costumes.” From the above text analysis and survey data, anthropomorphic narrative techniques are more prominent in animal video content. This involves a specific description method, namely, the anthropomorphism of animals. Since anthropomorphic elements often appear in animal videos, this study speculates that the various psychological mechanisms that people have towards animals in the media may be closely related to anthropomorphic narratives. From the current animal mukbang video content, there are anthropomorphic characteristics of animals mentioned in previous studies of animal videos, but there is a lack of research that summarizes the anthropomorphic elements in detail.

2.3. Animal anthropomorphism and audience acceptance

In the psychological literature, anthropomorphism is defined as the tendency of humans to see human characteristics or psychological states in non-human subjects, including natural entities, objects, or non-human animals, and to use human intentions, motivations, goals, or emotions as a basis for describing or explaining them [10]. Anthropomorphism is also related to humans’ search for a sense of social connection; specifically, people who feel lonely or chronically lack social connection with other humans may try to compensate by establishing a sense of human connection with non-human subjects [10]. From this point of view, the use of anthropomorphic narrative may allow audiences to have a similar sense of social connection when watching animal mukbang videos as when watching human mukbang. In addition, the motivations of viewers to watch animal videos are similar to those of viewers to watch human mukbang videos, specifically in terms of relieving stress in reality. For example, Myrick found that after watching videos about cats, respondents’ positive emotions such as happiness and satisfaction increased significantly, while negative emotions such as anxiety, sadness, and guilt decreased significantly [20]. Although Myrick’s study mentioned the positive effects of animal videos, it did not mention what specific content in the cat videos caused the audiences’ emotional changes. Based on the similar effects of anthropomorphic content and mukbang content in establishing a sense of connection, this study speculates that anthropomorphism in animal mukbang may also be a key factor in viewers’ choice to watch such videos. Therefore, by summarizing the anthropomorphic content framework in animal mukbang videos, it can be concluded which content themes in animal mukbang videos are like those in human mukbang, and thus infer the possible motivations of audiences to watch animal mukbang.

While animal anthropomorphism has become a common practice on social media, the impact seems to be mixed. First, some scholars believe that anthropomorphism has both positive and negative effects. Serpell pointed out that although anthropomorphism can enhance human’s moral consideration of animals and make us more sensitive to their welfare needs, it can sometimes lead to subjective bias and cause us to misunderstand the behavior of animals [6]. Taking companion animals as an example, Serpell pointed out that pet owners often express anger at behaviors that harm companion animals, which reflects their high concern for the welfare of this group of animals. However, pet owners may overestimate the cognitive abilities of their pets, for example, interpreting their pets’ inappropriate behaviors as intentional, which leads to inappropriate punishment [6]. Moreover, pet owners’ strong emotional attachment to their companion animals may also lead them to make decisions that prolong the pets’ suffering in order to achieve long-term companionship, such as refusing to euthanize terminally ill pets. The dual effects of anthropomorphism have also been noted by scholars in media studies. Scholars in the field of critical animal media studies (CAMS) point out that animal anthropomorphism in the media may reinforce anthropocentrism and thus neglect animal rights [21]. They prefer critical anthropomorphism, that is, statements about animals’ happiness, pain, hunger, stress, and so on, based on careful observation of animals, human empathy and intuition, and constantly improved and publicly verifiable predictions [22]. In addition, some scholars have critically evaluated different types of anthropomorphism to explore their rationality in terms of animal rights. Karlsson critically evaluated psychological (emotional) anthropomorphism and cultural (social) anthropomorphism [23]. The results showed that psychological anthropomorphism was considered more reasonable than cultural anthropomorphism. In other words, psychological anthropomorphism fully considers the differences between species and meets the standards of critical anthropomorphism.

In addition, some studies have investigated the receptiveness of anthropomorphism among different audiences. Stumpf et al. investigated how viewers perceive animal videos on social media, and this study focuses on the findings for two types of anthropomorphic content [19]. The results showed that when watching video content of “Animal did something extraordinary (facial expressions, gestures, vocalizations),” the most common emotion felt was “funny/entertainment,” while when watching video content of “animals wear human clothes or costumes,” the most common emotion felt was “anger/fright.” Their study also found that people who had professional experience with animals were more likely to perceive the animals’ suffering in the videos as being treated unfairly and were less likely to watch entertaining animal videos than those who had no experience with animals. From this perspective, it involves whether the audience’s professional experience with animals affects their perception of the rationality of animal anthropomorphism, in other words, whether the anthropomorphism of animals in the video is intended to please humans or to give animals the ability to speak for their own interests. In addition, according to Serpell, pet owners are generally more likely to anthropomorphize their pets [6]. This is often due to the emotional bond between pet owners and pets, which leads to owners attributing human-like emotions, intentions, and cognitive abilities to their pets. Martens et al. pointed out that young people who have more contact with animals are generally more concerned about animal welfare than those who do not own pets [24]. From this point of view, the audience’s experience of owning pets may also prompt them to perceive the degree of legitimacy of anthropomorphism. However, the results of Busch et al. showed that there was a relationship between pet ownership and attitudes toward animals, but this relationship was not particularly strong in real life, suggesting that other factors also play a crucial role in shaping these attitudes [25].

In general, both professional contact with animals and the experience of raising pets represent a strong sense of connection with animals. However, how this sense of connection affects viewers’ perceptions of anthropomorphism in animal videos is currently lacking. In order to expand the scope of this study, pet ownership will be used as the main variable instead of professional animal contact experience, which may involve people in specific occupations and may limit the scope of the results. Therefore, based on the above review of related research on mukbang, animal video content, and anthropomorphism, this study proposes the following research questions:

RQ1: What anthropomorphic content elements are represented in the animal mukbang on Chinese social media?

RQ2: Does the audience’s pet ownership experience affect their acceptance of anthropomorphic elements?

3. Methodology

This study adopts a sequential sampling design, first conducting a qualitative analysis of the video samples and then quantifying the audience acceptance. The specific methods include content analysis and questionnaire survey. First, this study uses content analysis to determine the anthropomorphic elements in animal mukbang videos on the two platforms. Second, a questionnaire survey further reveals the differences in the acceptance of anthropomorphism among different categories of audiences.

3.1. Content Analysis

In the summary of anthropomorphic elements, this study mainly conducts content analysis, including inductive and deductive processes. Armat et al. pointed out that in the process of content analysis, inductive and deductive methods are often used together, but the degree of dominance is different, which reflects the flexibility of content analysis [26]. Due to the lack of previous research summarizing the anthropomorphic elements in animal mukbang. Therefore, this study first uses inductive methods to directly encode the anthropomorphic elements in the selected video samples. Secondly, the process of theoretical deduction is carried out. According to previous studies such as psychological anthropomorphism and cultural anthropomorphism proposed by Karlsson [23], the anthropomorphic elements in animal mukbang are classified by summarizing the specific context.

This study selected video samples with over 10000 likes on Douyin and Xiaohongshu for analysis, with a total of 60 short video samples selected, and 30 samples selected from the two platforms respectively. The lowest number of likes is 10000, and the highest number of likes is around 2 million. The anthropomorphic elements in each video sample were identified and encoded, and these elements were classified according to specific theories.

After sample collection, the first thing to do is to encode the anthropomorphic elements in the video text. Secondly, the coding results are classified according to the various anthropomorphic themes summarized from the theory. Due to the lack of classification and summary of anthropomorphism in the media, this study found that most of the discussions on anthropomorphism focus on the psychological and physical aspects through literature review and related theoretical research. First, according to Karlsson, psychological anthropomorphism is the attribution of human-like thoughts and emotions to animals [23], and likewise, Waytz et al. point out that anthropomorphism also includes psychological aspects, those mental abilities unique to humans, such as being conscious, having definite intentions, or emotions (e.g., joy, pride, shame, guilt) [27]. From this point of view, two of these themes can be summarized as intention and emotion in terms of mental anthropomorphism. In addition to this, according to previous reviews, psychological anthropomorphism meets the criteria of critical anthropomorphism to some extent, and both critical anthropomorphism and CAMS emphasize the idea of seeing animals as individuals rather than groups. From Weil’s analysis of orangutan photographs, each orangutan looks different, and there may be different stories behind them, so they may look deep or vicissitudes, this involves a description of personalities and experiences [7]. Prato-Previde et al. also pointed out that anthropomorphic animals need to endow them with human-like personalities, emotions, and intentions. Therefore, personality can also become one of the themes [10].

Furthermore, Karlsson also explored cultural (social) anthropomorphism, using concepts from human culture to explain animal relationships, the human traits imparted to animals are cultural stereotypes that we perceive as part of human culture and social life impressions, such as gender [23]. There are also manifestations of human social issues such as morality and dignity. Based on this, “culture” is proposed as one of the themes.

In addition to psychological and cultural anthropomorphism, research on anthropomorphism also focuses on imitating human characteristics, mainly physical characteristics, such as human-like “faces” or movements [10]. Besides, according to Waytz et al., the more similar an object is to humans in behavior or appearance, the more likely it is to be anthropomorphized. Therefore, the other two themes would be appearance and behavior [27]. Finally, based on the investigation of Weil [7], this study also pays attention to the anthropomorphism of the environment, as he says in this artificial environment, the image of animals seems unreal. After relevant investigations, it was found that very few studies focused on the environment, so this is also the innovation of this study, trying to summarize the elements related to the anthropomorphism of the environment in animal mukbang. In summary, the framework themes of anthropomorphism based on theory include intention, emotion, personality, appearance, behavior, environment, and culture. After that, this study carefully analyzed the selected video samples and matched the specific manifestations of anthropomorphism in the videos to each theme (see the Appendix for encoding instructions).

3.2. Questionnaire Survey

The questionnaire sample designed in this study involves audiences of different age groups, but according to the collected data, most of the respondents are between the ages of 18 and 25. The questionnaire started on April 12th, 2023, and ended on April 23rd, 2023, with a total of 170 people completing the questionnaire. The survey questionnaire focuses on participants’ experience of raising pets and their acceptance of viewing relevant anthropomorphic images. To analyze different types of data, quantitative analysis was used to present the differences in the data. The setting of questionnaire questions was mainly based on the anthropomorphic elements in animal mukbang, and the evaluation criteria are based on Hall’s three decoding models [28].

A Likert scale was set up in the questionnaire to assess the participants’ acceptance of each anthropomorphic element. The ordinal items ranged from 1 to 5, namely “very unacceptable,” “unacceptable,” “average,” “acceptable” and “very acceptable.” The ratings of each acceptance level were interpreted in the questionnaire according to Hall’s three decoding models, namely dominant-hegemonic position, negotiated position, and oppositional position [28]. The dominant-hegemonic position refers to the audience’s understanding of the implicit meaning in the text from a complete and direct perspective, and the audience’s interpretation is commensurate with the meaning encoded in the text. The negotiated position accepts the overall view of the encoding but disagrees with the details and may insist on specific exceptions. The oppositional position means that the audience can fully understand the literal and connotation changes of the event but interpret the information in a way that is opposite to the “preferred meaning.” Audiences whose ratings showed “very unacceptable” and “unacceptable” would represent the oppositional position. The explanation for these two levels of acceptance in the questionnaire is, “I cannot identify this anthropomorphic element, or I can identify this anthropomorphic element, but I do not approve or accept such anthropomorphism of animals by the creator.” The “average” level of acceptance represents the negotiated position, and the explanation for this level in the questionnaire is, “I can identify this anthropomorphism and to some extent, I can accept the creator’s anthropomorphism of animals, but I need to judge whether to fully accept it based on the actual situation, as some may be excessive.” Finally, audiences whose ratings showed “acceptable” and “very acceptable” would represent dominant-hegemonic positions, and the explanation in the questionnaire is, “I can recognize this kind of anthropomorphism, and I fully accept the presence of this anthropomorphic element in animal mukbang.”

4. Findings

4.1. Summary of anthropomorphic elements in animal mukbang videos

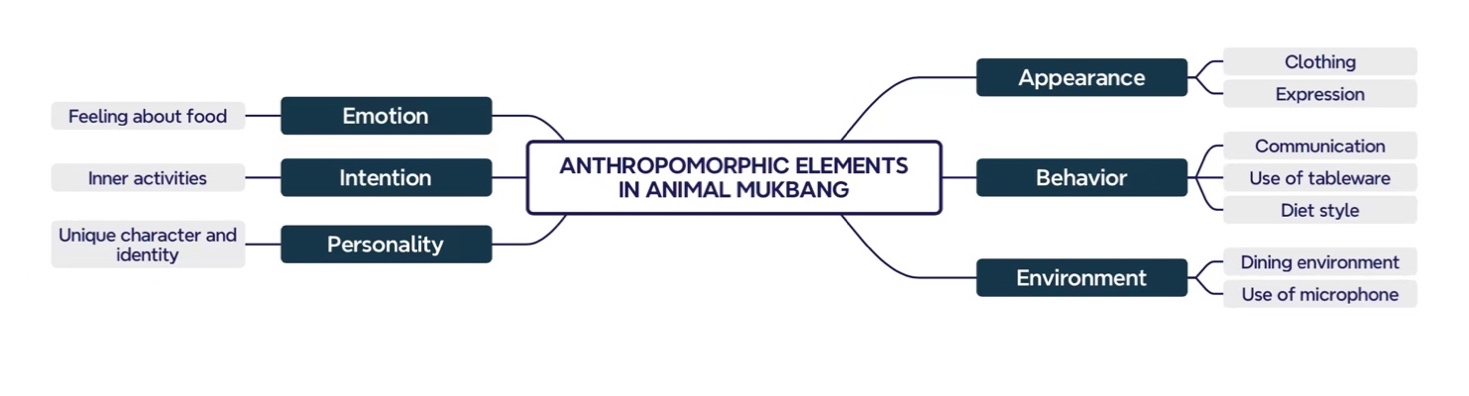

This study conducted anthropomorphic identification and analysis on 60 video samples, aiming to induce corresponding codes for seven themes. The identified codes include “Clothing,” “Expression,” “Communication,” “Diet style,” “Use of tableware,” “Dining environment,” “Use of microphone,” “Feeling about food,” “Inner activities” and “Unique character and identity.” The classification results are shown in Figure 1. Regarding the theme of “culture” based on cultural anthropomorphism, this study did not identify relevant elements in the video samples. In other words, there seems to be no manifestation of issues related to human social relations in animal mukbang.

Figure 1: Anthropomorphic text frame for animal mukbang in on Chinese social media.

From the results, it can be seen that the reliability of the each code in this study is “Environment” (Kappa=0.864), “Use of tableware” (Kappa=0.937), “Diet style” (kappa=0.924), “Communication” (Kappa=0.914), “Clothing” (Kappa=0.931), “Expression” (Kappa=0.880), “Unique character and identity” (Kappa=0.856), “Feeling about food” (Kappa=0.952), “Inner activities” (Kappa=0.879) and “Use of microphone” (Kappa=0.880). According to the guidelines given by Landis and Koch (1977, p. 165), less than 0.00 indicates poor agreement, 0.00-0.02 indicates slight agreement, 0.21-0.40 indicates fair agreement, 0.41-0.60 indicates moderate agreement, 0.61-0.80 indicates substantial agreement and 0.81-1.00 means almost perfect agreement. All results of this study meet Kappa>0.80, and the coding consistency is high.

4.2. Audience acceptance of anthropomorphism

To explore whether pet ownership will affect the acceptance of different anthropomorphic elements by different audiences, the T-test was used to verify whether there is a difference between the two groups of categorical data. According to the summarized text frames, this study carefully investigated and analyzed the audience’s acceptance of each anthropomorphic element. The audience’s acceptance of each element is shown in Table 1.

Table 1: The level of acceptance of each anthropomorphic element by different audiences.

T-test Analysis | ||||

Do you have pets now or have you ever owned pets in the past (Mean ± SD) | t | p | ||

Pet owners (n=108) | Non-pet owners (n=62) | |||

Do you accept the dining environment where humans appear in animal mukbang, such as dining tables? (Dining environment) | 3.54±1.20 | 3.03±1.25 | 2.593 | 0.010* |

Do you accept images of animals using tableware? (Use of tableware) | 3.34±1.16 | 2.90±1.33 | 2.253 | 0.026* |

Do you accept the diet style of humans appearing in animal mukbang (such as hot pot, Michelin dinner etc.)? (Diet style) | 3.01±1.22 | 2.55±1.25 | 2.351 | 0.020* |

Do you accept the use of microphones in animal mukbang? (Use of microphone) | 2.99±1.24 | 2.47±1.20 | 2.678 | 0.008** |

Do you accept the appearance of communicating with pets in the animal mukbang? (Communication) | 3.73±1.01 | 3.27±1.13 | 2.716 | 0.007** |

Do you accept clothing for animals? (Clothing) | 3.79±0.97 | 3.58±1.06 | 1.291 | 0.199 |

Do you accept the interpretation of animal expressions in animal mukbang? (Expression) | 3.78±0.93 | 3.53±1.00 | 1.609 | 0.110 |

Do you accept the unique character/identity given to animals in animal mukbang? (Unique character and identity) | 3.78±0.86 | 3.26±1.12 | 3.401 | 0.001** |

Do you accept the interpretation of pets’ feelings towards food in animal mukbang? (Feeling about food) | 3.73±0.92 | 3.35±1.03 | 2.458 | 0.015* |

Do you accept text or dubbing that imagines the inner activities of animals in animal mukbang? (Inner activities) | 3.68±1.00 | 3.34±1.04 | 2.082 | 0.039* |

*p<0.05**p<0.01 | ||||

The audience’s acceptance of each element is shown in Table 1. Among them, there is no significant difference in the respondents’ acceptance of the two anthropomorphic elements “Clothing” and “Expression” between pet owners and non-pet owners (t=1.291, p=0.199>0.05 and t=1.609, p=0.110>0.05), which shows that pet ownership does not affect the audience’s acceptance of these two anthropomorphic elements. Besides, pet owners and non-pet owners show significant differences in their acceptance of the remaining eight anthropomorphic elements in animal mukbang, among which “Use of microphone,” “Communication,” and “Unique character and identity” are significant at p < 0.01, and “Environment”, “Use of tableware”, “Diet style”, “Feeling about food” and “Inner activities” are significant at p < 0.05. Specifically, pet owners tend to accept the above eight anthropomorphic elements more than non-pet owners. From the average score of the audience’s acceptance of various anthropomorphisms, pet owners are more likely to express a dominant-hegemonic attitude towards anthropomorphic elements, while non-pet owners are more likely to present a negotiation attitude. In general, pet ownership has greatly promoted the audience’s acceptance of the anthropomorphic elements in animal mukbang videos.

5. Discussion

This study first systematically summarizes the anthropomorphic elements in animal mukbang videos on Douyin and Xiaohongshu. From the results of encoding, although animal mukbang videos are a short video format with a much shorter narrative time than other visual media, in terms of anthropomorphic presentation, they almost cover most of the elements proposed in a series of anthropomorphic theories and related studies reviewed in this study. These include anthropomorphism of appearance and behavior, psychological anthropomorphism, and environmental anthropomorphism. These elements can also be reflected in other media, such as movies, documentaries, and TV shows. As O’Meara summarized, different types of animal videos are usually presented in different ways, and similarities can always be found in them [18]. However, through the careful identification of video samples, this study eliminated the theme of “culture”, which means that there is no visual presentation directly corresponding to the theme in the video samples.

From the specific cases of cultural anthropomorphism, its discussion direction is mostly based on broader social topics, such as stereotypes, ideology, moral criticism, and so on. For example, Karlsson pointed out that in wildlife TV programs, the transfer of human characteristics to animals reaffirms stereotypes such as gender and sexual orientation [23]. This often requires a detailed interpretation of animal behavior and relationships in the video text. Such carefully selected images may also perpetuate relevant stereotypes in the public’s cognition of animals. Haraway also suggested that the visualization of animals is used to reaffirm patriarchal values that transcend physical vulnerability [29]. For the animal mukbang, the focus is on interaction with the audience, and the scene events are relatively single. The direction of anthropomorphism mostly starts from the visible environmental elements of the animals themselves and their surroundings, rarely placing them in a larger human social context for the narrative.

In the audience survey, the results of this study show that pet ownership can make the audience more accepting of anthropomorphism in animal mukbang in some ways, but this is not absolute. In other words, because this study has a more detailed classification of the types of anthropomorphism, sometimes the impact of this relationship is very insignificant. For example, regarding the acceptance of the anthropomorphic element “Clothing,” both pet owners and non-pet owners among the participants showed greater acceptance. This result is different from the result mentioned in Stumpf’s study that the most common emotion felt by the audience when watching the video content of “animals wear human clothes or costumes” is “anger/fright” [19]. This means that no matter how close the audience is to the animals, they will not perceive the negative impact of this anthropomorphic form on the animal protagonist when watching animal mukbang. In addition, both pet owners and non-pet owners expressed acceptance of the element “Expression,” which is basically similar to the positive emotion generated by the audience when watching the facial expression of animals in Stumpf’s study [19]. Except for “Clothing” and “Expression”, the audience acceptance of other anthropomorphic elements shows that pet owners are more accepting than non-pet owners, which largely proves the fact that pet owners are generally more likely to anthropomorphize their pets as mentioned in Serpell’s study [6].

The results of this study on the audience survey also quantified the relationship between critical personification and audience experience. Although the classification process is not based on critical personification, based on the research of relevant scholars on critical anthropomorphism and their recognition of Karlsson’s psychological anthropomorphism, some anthropomorphic elements summarized in this study are also in line with critical anthropomorphism standards [23]. For example, “Communication,” “Unique character and identity,” and “Feeling about food,” these elements introduce the idea and uniqueness of each animal, just as scholars from CAMS advocated treating each animal as an individual rather than a collective [21], and Burghardt proposed a critical anthropomorphic description of animal behavior, emotion, and social relationships [22]. In summary, these three elements meet the critical anthropomorphic standards after in-depth understanding, in the survey of audience’s acceptance, it also shows that among the audience with pets, the proportion of the audience who chooses “acceptable” and “very acceptable” is larger. This roughly explains how the relationship between the audience and animals affects the perception of critical anthropomorphism, which is an unresolved part of previous research.

However, from the results of this study, pet owners may also ignore certain considerations of the individual uniqueness of animals. For example, pet owners may be more accepting of the anthropomorphic element of “Environment.” Previous studies have shown that animals may appear unreal and lose their own uniqueness in such artificial environments [7]. Pet owners’ acceptance of the artificial environments in animal mukbang may be due to their acceptance of the creative conventions of human mukbang videos. Nevertheless, due to the lack of open-ended questions raised in this study and the inability to collect different perspectives from the audience, further research is needed on the impact of anthropomorphic environments. In this case, the experience of interacting with animals does not directly affect the recognition, negotiation, or rejection of the content. There may be other reasons that need further verification. As Hodkinson explains in Hall’s three decoding models, audience responses to media are related to the socio-economic context [30]. Although this study provides targeted explanations for audience experience and acceptance based on Hall’s three decoding models, it may lead to a broader context being overlooked.

6. Conclusion

This study answered two research questions about the anthropomorphic elements in animal feeding broadcasts through content analysis and questionnaire surveys: What anthropomorphic content elements are represented in the animal mukbang on Chinese social media; and does the audiences’ pet ownership affect their acceptance of anthropomorphic elements? The findings show that most anthropomorphic elements can be recognized in animal mukbang, except for cultural anthropomorphism without direct visual representation. Besides, pet ownership can affect audience acceptance of some anthropomorphic elements.

This study is not without limitations. In addition to the neglect of the broader socio-economic context mentioned above when discussing environmental anthropomorphism, there are also shortcomings in sample selection and audience survey. When selecting video samples, this study only focuses on the number of likes, to judge the popularity of the video on the short video platform. However, when performing text recognition, it was found that among the video samples with more than 10,000 likes, there were multiple videos from one creator. The creative and narrative habits of each author may not have changed much, which may cause this research to not pay attention to the diversity of creation. In addition, the audience survey mainly focuses on the relationship between the audience’s experience of pet ownership and their level of anthropomorphic acceptance, and the social background may not be limited to the premise set in this study, in other words, the audience’s experience with animals may not be limited to pet ownership. Regarding the audience’s position on anthropomorphism in video texts, and whether there are other influencing factors, there is still a wider audience social survey to be done. Moreover, the naming of the two audience groups involved in this study is relatively broad, with “pet owners” and “non-pet owners” only describing the surface state of the audience, and the audience’s feelings, cognition, and other aspects of animals are not described. Therefore, as previously mentioned, open-ended questions or interviews may be needed to obtain different interpretations through discourse analysis. Finally, although this study to some extent explains the main anthropomorphic presentation methods of animal mukbang on Chinese social media, further research is needed on the relationship between anthropomorphism and audience in broader media, and the rationality of using animal anthropomorphism in media needs to be explored.

References

[1]. Zhang, C. (2020). Gou Chi Niupai, Mao Chi Longxia, 1000Wan Ren Weiguan De Chongwu Chibo Shi Zenyang De Shengyi? [Dogs eat steak, cats eat lobster, what kind of business is the pet mukbang watched by 10 million people?] Retrieved from: https://m.jiemian.com/article/4617781.html

[2]. NetEase. (2020). Kepa De Chongwu Chibo! [Terrible pet eating show!] Retrieved from https://www.163.com/dy/article/FMFM9GSU051197OF.html

[3]. Kang, E., Lee, J., Kim, K. H., & Yun, Y. H. (2020). The popularity of eating broadcast: Content analysis of “mukbang” YouTube videos, media coverage, and the health impact of “mukbang” on public. Health informatics journal, 26(3), 2237-2248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059

[4]. Anjani, L., Mok, T., Tang, A., Oehlberg, L., & Goh, W. B. (2020). Why do people watch others eat food? An Empirical Study on the Motivations and Practices of Mukbang Viewers. Proceedings of the 2020 CHI conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376567

[5]. Choe, H. (2020). Talking the cat: Footing lamination in a Korean livestream of cats mukbang. Journal of Pragmatics, 160, 60-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2020.02.009\

[6]. Serpell, J. A. (2019). How happy is your pet? The problem of subjectivity in the assessment of companion animal welfare. Animal Welfare, 28(1), 57-66. https://doi.org/10.7120/09627286.28.1.057

[7]. Weil, K. (2013). Thinking animals: Why animal studies now? Columbia University Press.

[8]. Malamud, R. (2015). Looking at Humans Looking at Animals. In N. Almiron, M. Cole, & C. P. Freeman (Eds), Critical Animal and Media Studies (pp. 154-168). Routledge.

[9]. Geerdts, M. S., Van de Walle, G. A., & LoBue, V. (2016). Learning about real animals from anthropomorphic media. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 36(1), 5-26. DOI: 10.1177/0276236615611798

[10]. Prato-Previde, E., Basso Ricci, E., & Colombo, E. S. (2022). The Complexity of the Human–Animal Bond: Empathy, Attachment and Anthropomorphism in Human–Animal Relationships and Animal Hoarding. Animals, 12(20), 2835. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12202835

[11]. Sultana, S. F. S., & Das, M. (2022). Content Analysis Of Mukbang Videos: Preferences, Attitudes And Concerns. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(9), 4811-4822. Retrieved from: https://mail.journalppw.com/index.php/jpsp/article/view/13360

[12]. Ruggiero, T. E. (2000). Uses and gratifications theory in the 21st century. Mass communication & society, 3(1), 3-37. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327825MCS0301_02

[13]. Lariscy, R.W., Tinkham, S. F., & Sweetser, K. D. (2011). Kids these days: Examining differences in political uses and gratifications, internet political participation, political information efficacy, and cynicism on the basis of age. American Behavioral Scientist, 55(6), 749-764. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764211398091

[14]. Song, H. G., Kim, Y. S., & Hwang, E. (2023). How attitude and para-social interaction influence purchase intentions of Mukbang users: A mixed-method study. Behavioral Sciences, 13(3), 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13030214

[15]. Kircaburun, K., Harris, A., Calado, F., & Griffiths, M. D. (2021). The psychology of mukbang watching: A scoping review of the academic and non-academic literature. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19, 1190-1213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00211-0

[16]. Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 351–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059

[17]. Zhang, X., & Zhu, L. (2023). Research on the Narrative Feature of the Short Video. Probe-Media and Communication Studies, 5(5). https://doi.org/10.59429/pmcs.v5i5.958

[18]. O’Meara, R. (2014). Do cats know they rule YouTube? Surveillance and the pleasures of cat videos. M/C Journal, 17(2). https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.794

[19]. Stumpf, A., Herbrandt, S., Betting, L., Kemper, N., & Fels, M. (2024). Societal Perception of Animal Videos on Social Media—Funny Content or Animal Suffering? A Survey. Animals, 14(15), 2234. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14152234

[20]. Myrick, J. G. (2015). Emotion regulation, procrastination, and watching cat videos online: Who watches Internet cats, why, and to what effect?. Computers in human behavior, 52, 168-176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.001

[21]. Merskin, D. (2015). Media Theories and the Crossroads of Critical Animal and Media Studies. In N. Almiron, M. Cole, & C. P. Freeman (Eds), Critical Animal and Media Studies (pp. 11-25). Routledge.

[22]. Burghardt, G. M. (1997). Amending Tinbergen: A Fifth Aim for Ethology. In R. W. Mitchell, N. S. Thompson, and H. L. Miles (Eds.), Anthropomorphism, Anecdotes, and Animals (pp. 254–276). Albany: State University of New York Press.

[23]. Karlsson, F. (2012). Critical anthropomorphism and animal ethics. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 25, 707-720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-011-9349-8

[24]. Martens, P., Hansart, C., & Su, B. (2019). Attitudes of young adults toward animals—the case of high school students in Belgium and The Netherlands. Animals, 9(3), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9030088

[25]. Busch, G., Schütz, A., Hölker, S., & Spiller, A. (2022). Is pet ownership associated with values and attitudes towards animals?. Animal Welfare, 31(4), 447-454. https://doi.org/10.7120/09627286.31.4.011

[26]. Armat, M. R., Assarroudi, A., & Rad, M. (2018). Inductive and deductive: Ambiguous labels in qualitative content analysis. The Qualitative Report, 23(1). http://eprints.medsab.ac.ir/id/eprint/300

[27]. Waytz, A., Epley, N., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Social cognition unbound: Insights into anthropomorphism and dehumanization. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(1), 58-62. DOI: 10.1177/0963721409359302

[28]. Hall, S. (2003). Encoding/decoding∗. In Culture, media, language (pp. 117-127). Routledge.

[29]. Haraway, D. (1989). Primate visions. London: Routledge.

[30]. Hodkinson. (2016). Media, culture and society: an introduction (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Cite this article

Liu,X. (2024). Animal Anthropomorphism in Chinese Social Media and Audience Acceptance: A Case Study of Animal Mukbang. Communications in Humanities Research,64,27-41.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Zhang, C. (2020). Gou Chi Niupai, Mao Chi Longxia, 1000Wan Ren Weiguan De Chongwu Chibo Shi Zenyang De Shengyi? [Dogs eat steak, cats eat lobster, what kind of business is the pet mukbang watched by 10 million people?] Retrieved from: https://m.jiemian.com/article/4617781.html

[2]. NetEase. (2020). Kepa De Chongwu Chibo! [Terrible pet eating show!] Retrieved from https://www.163.com/dy/article/FMFM9GSU051197OF.html

[3]. Kang, E., Lee, J., Kim, K. H., & Yun, Y. H. (2020). The popularity of eating broadcast: Content analysis of “mukbang” YouTube videos, media coverage, and the health impact of “mukbang” on public. Health informatics journal, 26(3), 2237-2248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059

[4]. Anjani, L., Mok, T., Tang, A., Oehlberg, L., & Goh, W. B. (2020). Why do people watch others eat food? An Empirical Study on the Motivations and Practices of Mukbang Viewers. Proceedings of the 2020 CHI conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376567

[5]. Choe, H. (2020). Talking the cat: Footing lamination in a Korean livestream of cats mukbang. Journal of Pragmatics, 160, 60-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2020.02.009\

[6]. Serpell, J. A. (2019). How happy is your pet? The problem of subjectivity in the assessment of companion animal welfare. Animal Welfare, 28(1), 57-66. https://doi.org/10.7120/09627286.28.1.057

[7]. Weil, K. (2013). Thinking animals: Why animal studies now? Columbia University Press.

[8]. Malamud, R. (2015). Looking at Humans Looking at Animals. In N. Almiron, M. Cole, & C. P. Freeman (Eds), Critical Animal and Media Studies (pp. 154-168). Routledge.

[9]. Geerdts, M. S., Van de Walle, G. A., & LoBue, V. (2016). Learning about real animals from anthropomorphic media. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 36(1), 5-26. DOI: 10.1177/0276236615611798

[10]. Prato-Previde, E., Basso Ricci, E., & Colombo, E. S. (2022). The Complexity of the Human–Animal Bond: Empathy, Attachment and Anthropomorphism in Human–Animal Relationships and Animal Hoarding. Animals, 12(20), 2835. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12202835

[11]. Sultana, S. F. S., & Das, M. (2022). Content Analysis Of Mukbang Videos: Preferences, Attitudes And Concerns. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(9), 4811-4822. Retrieved from: https://mail.journalppw.com/index.php/jpsp/article/view/13360

[12]. Ruggiero, T. E. (2000). Uses and gratifications theory in the 21st century. Mass communication & society, 3(1), 3-37. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327825MCS0301_02

[13]. Lariscy, R.W., Tinkham, S. F., & Sweetser, K. D. (2011). Kids these days: Examining differences in political uses and gratifications, internet political participation, political information efficacy, and cynicism on the basis of age. American Behavioral Scientist, 55(6), 749-764. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764211398091

[14]. Song, H. G., Kim, Y. S., & Hwang, E. (2023). How attitude and para-social interaction influence purchase intentions of Mukbang users: A mixed-method study. Behavioral Sciences, 13(3), 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13030214

[15]. Kircaburun, K., Harris, A., Calado, F., & Griffiths, M. D. (2021). The psychology of mukbang watching: A scoping review of the academic and non-academic literature. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19, 1190-1213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00211-0

[16]. Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 351–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059

[17]. Zhang, X., & Zhu, L. (2023). Research on the Narrative Feature of the Short Video. Probe-Media and Communication Studies, 5(5). https://doi.org/10.59429/pmcs.v5i5.958

[18]. O’Meara, R. (2014). Do cats know they rule YouTube? Surveillance and the pleasures of cat videos. M/C Journal, 17(2). https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.794

[19]. Stumpf, A., Herbrandt, S., Betting, L., Kemper, N., & Fels, M. (2024). Societal Perception of Animal Videos on Social Media—Funny Content or Animal Suffering? A Survey. Animals, 14(15), 2234. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14152234

[20]. Myrick, J. G. (2015). Emotion regulation, procrastination, and watching cat videos online: Who watches Internet cats, why, and to what effect?. Computers in human behavior, 52, 168-176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.001

[21]. Merskin, D. (2015). Media Theories and the Crossroads of Critical Animal and Media Studies. In N. Almiron, M. Cole, & C. P. Freeman (Eds), Critical Animal and Media Studies (pp. 11-25). Routledge.

[22]. Burghardt, G. M. (1997). Amending Tinbergen: A Fifth Aim for Ethology. In R. W. Mitchell, N. S. Thompson, and H. L. Miles (Eds.), Anthropomorphism, Anecdotes, and Animals (pp. 254–276). Albany: State University of New York Press.

[23]. Karlsson, F. (2012). Critical anthropomorphism and animal ethics. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 25, 707-720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-011-9349-8

[24]. Martens, P., Hansart, C., & Su, B. (2019). Attitudes of young adults toward animals—the case of high school students in Belgium and The Netherlands. Animals, 9(3), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9030088

[25]. Busch, G., Schütz, A., Hölker, S., & Spiller, A. (2022). Is pet ownership associated with values and attitudes towards animals?. Animal Welfare, 31(4), 447-454. https://doi.org/10.7120/09627286.31.4.011

[26]. Armat, M. R., Assarroudi, A., & Rad, M. (2018). Inductive and deductive: Ambiguous labels in qualitative content analysis. The Qualitative Report, 23(1). http://eprints.medsab.ac.ir/id/eprint/300

[27]. Waytz, A., Epley, N., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Social cognition unbound: Insights into anthropomorphism and dehumanization. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(1), 58-62. DOI: 10.1177/0963721409359302

[28]. Hall, S. (2003). Encoding/decoding∗. In Culture, media, language (pp. 117-127). Routledge.

[29]. Haraway, D. (1989). Primate visions. London: Routledge.

[30]. Hodkinson. (2016). Media, culture and society: an introduction (2nd ed.). SAGE.